Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate surgical experience among current doctors appointed into ophthalmology training posts since the introduction of the Modernising Medical Careers programme. Additionally, to identify regional variations in surgical experience and training programme delivery.

Design

A cross-sectional survey.

Setting

The UK's four largest deaneries (Schools of Ophthalmology).

Participants

Trainee ophthalmologists, all having completed three or more years of training, who were appointed to the new ophthalmic specialty training programme.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The mean annual surgical rate for each deanery in phacoemulsification cataract extractions and experience in other common elective and emergency surgical operations. Second, to calculate the mean timetabled clinical activity.

Results

The responses of 40 doctors were analysed, with a response rate of 83%. Overall, the phacoemulsification rate was 73.52±29.24 operations/year. This was significantly higher in the South Thames Deanery (99.69±26.16, p=0.0005) and significantly lower in the North Western Deanery (48.08±19.72, p=0.0008). The annual mean complex cataract rate was 5.21±4.38. Only 40% were confident in dealing with the most common complication of cataract surgery (vitreous loss). The mean trabeculectomy (surgery for glaucoma) rate was 0.47±1.16 and for squint surgery it was 3.54±2.82 operations/year. Regarding the common ocular trauma surgery, 42.5% had not sutured a corneal laceration and 60% a globe rupture. 50% thought the training programme would adequately prepare them surgically. The timetabled clinical activity was highest in the South Thames Deanery (48.17 h/week) and lowest in the North Western Deanery (40.82 h/week) due to variations in the European Working Time Directive implementation and on-call commitments.

Conclusions

Significant regional variations in surgical training experience exist between UK deaneries, particularly with respect to cataract surgery, and they appear to be correlated to timetabled activity. Experience and confidence levels in managing complex cataract surgery and complications were low and experience with previously commonly performed elective and emergency operations was minimal. Although doctors from all the regions surveyed were very likely to achieve the minimum cataract extractions required for specialist training completion, we have identified shortcomings of the current training programme that need attention.

Keywords: Education & training (see Medical Education & Training)

Article summary.

Article focus

The UK ophthalmology training has undergone multiple changes over a short period of time following the introduction of Modernising Medical Careers, the European Working Time Directive and the Ophthalmic Specialty Training programme.

With some of the first recruits under the new training system approaching completion of specialist training, there are no published data yet on the impact of all these changes on ophthalmic surgical training.

We evaluated the current level of surgical experience among ophthalmic trainees across the UK.

Key messages

Doctors training under the new system are likely to achieve the minimum number of cataract operations required, but probably fewer than would have been obtained under the previous training system.

There appears to be a wide regional variation in surgical experience and timetabled clinical activity among ophthalmology trainees in the UK.

Current trainees could be getting less experience with previously commonly performed operations such as squints and trabeculectomies, and in dealing with trauma.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Limitations include reliance on self-reported data, from only four deaneries, and the possibility that further surgical experience in the final years of training could affect these results.

Strengths include surveying the four largest deaneries in the UK which train nearly 50% of ophthalmologists and sampling 50% of trainees who would potentially meet the inclusion criteria.

Introduction

Postgraduate medical training in the UK underwent significant reform following the introduction of the Modernising Medical Careers (MMC) programme in 2007. The aim of MMC was to produce an appropriately skilled workforce using an efficient career path for doctors.1 In order to achieve this, recruitment and selection into specialist training, as well as the structure of postgraduate medical education and training, were radically changed. These changes were made with the additional constraints of a 48 h maximum working week, dictated by the European Working Time Directive (EWTD), which the National Health Service (NHS) aimed to achieve 100% compliance with by August 2009.2

Until 2007, junior doctors wishing to train in ophthalmology, in common with other surgical specialties, were required to competitively enter into a senior house officer rotation in ophthalmology. This typically lasted at least 3 years, by the end of which they were expected to be competent in basic cataract surgery and complete the Membership of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists (MRCOphth) or an equivalent examination. They subsequently applied for a national training number for a further four and a half years of higher surgical training. This was intensely competitive and many doctors spent time undertaking formal research in order to improve their chances of successful application.

Following MMC, ophthalmic specialty training (OST) has been introduced which aims to take doctors from foundation year 2 to inclusion on the specialist register within 7 years. The main entry point onto the programme, at the end of the foundation programme, has less than 80 posts available annually (table 1).3 OST is currently delivered by separate ‘Schools of Ophthalmology’ based in 15 deaneries throughout the UK. The largest deanery of London and Kent, Surrey and Sussex has a single application process, but successful applicants subsequently spend the duration of their training in one of the two distinct training programmes.

Table 1.

UK deaneries by the average number of OST places per year at the time of data collection

| Deanery | OST posts per year3 |

|---|---|

| London South Thames and Kent, Surrey & Sussex | 12 |

| London North Thames | 11 |

| West Midlands | 8 |

| North Western | 5 |

| East of England | 5 |

| Northern | 5 |

| Wales | 5 |

| East Midlands | 4 |

| Mersey | 4 |

| Scotland | 4 |

| Oxford | 3 |

| Peninsular | 3 |

| Severn | 3 |

| Wessex | 3 |

| Yorkshire and Humberside | 2 |

| Northern Ireland | 2 |

OST, ophthalmic specialty training.

At the conclusion of OST, trainees are required to complete the Fellowship of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists (FRCOphth) examinations, 180 different learning objectives4 and a log book requiring a minimum of 419 surgical procedures to be performed as stipulated by the training committee (table 2).5 Cataract surgery is the most frequently performed surgical procedure in the Western world and 300 cataract operations are required over 7 years in OST compared with 300 for specialist registrars in the previous system over four and a half years.6 In fact, the minimum number of surgical procedures required following the introduction of MMC remain unchanged from that required in the previous training system.

Table 2.

Minimum number of surgical procedures required at the end of ophthalmic specialty training5

| Procedure | Minimum number required |

|---|---|

| Small incision cataract | 300 |

| Strabismus | 20 |

| Oculoplastic and lacrimal (non-ptosis) | 40 |

| Procedures for glaucoma (including laser) | 30 |

| Vitreoretinal | 20* |

| Corneal graft | 6* |

| Ptosis | 3* |

*Including assistance in operation.

The more structured and closely supervised surgical training programmes following MMC have been designed to compensate for the reduced time spent in training, but this issue has caused much anxiety among junior doctors as well as those delivering training.7 To date, there are no published data on the impact of the new OST on ophthalmic surgical training. Our study therefore aimed to evaluate the current level of surgical experience and how training is currently being delivered among doctors appointed in the new OST programme in the UK. We also wished to determine if there are any regional variations in training experience and delivery, as well as if trainees are likely to attain the minimum procedures required and how their surgical experiences compare with those recently completing training under the previous system.

Materials and methods

Questionnaire

A questionnaire to collect the objective and categorical data parameters was designed and internally tested by all six authors. The survey was disseminated via email by authors from each respective deanery in the form of a protected MS Excel worksheet. This meant that it was only possible for those participating in the survey to enter data in the correct format in the appropriate cells. These data cells were linked to a second worksheet where the raw data were extracted anonymously and collated by the lead author. The complete questionnaire is available to view as a supplementary file, but in brief, the parameters assessed included:

Demographic and postgraduate training data.

Cataract and associated surgery numbers performed as a primary surgeon (defined as a trainee completing the entire operation or the vast majority of the operation, with or without supervision). Complex cataract operations were defined as white cataract, small pupils requiring additional surgical manipulation and the presence of pseudoexfoliation (implying weak zonules).

Other common elective and emergency surgical numbers performed by a primary surgeon including trabeculectomy (surgery for glaucoma), squint operations, lid and corneal lacerations and globe ruptures.

Subjective questions on surgical confidence and adequacy of surgical training.

Timetables were also collated and analysed from hospitals where the training programme for each deanery was centred.

Deaneries surveyed

The four largest deaneries in the UK completed questionnaires at the end of the 2011 academic year (July):

London South Thames (which for ophthalmology includes the Kent, Surrey and Sussex deanery)

London North Thames (rotation centred around Moorfields Eye Hospital)

West Midlands (rotation centred around Birmingham and Midlands Eye Centre)

North Western (rotation centred around Manchester Royal Eye Hospital)

The training programme in each of these deaneries exposed trainees to hands-on clinical and surgical experience from the beginning of their first year of ophthalmic specialist training. As per the Royal College of Ophthalmologists training guidelines, supervised surgical training was introduced as a staged method involving selected patients.8 The standard suggested timetable included two dedicated theatre sessions/week, with only one junior trainee present. The non-surgical training programme in the early years (years 1–3) involved clinical exposure across subspecialties with emphasis on concentrated experience later in training. The general composition of timetables was similar for trainees between years 1 and 6, whereas year 7 generally involves subspecialty trainee selected components with more variability in timetables, according to the needs of each specific specialty. There was no significant deviation from these Royal College guidelines in any of the deaneries surveyed, unless needed in specific circumstances.

Respondents

A contact list of all trainees in each of the deaneries surveyed was used to identify those eligible. Inclusion criteria were doctors who had entered into the new OST programme and were at the end of their third year of training or above (equivalent to specialist registrars in the previous system). Exclusion criteria were doctors who transferred between deaneries during their OST.

In the smallest deanery that we surveyed, North Western, we identified a maximum of 16 trainees who would meet these inclusion and exclusion criteria. It was therefore decided to randomly select 12 trainees from each deanery who were invited to participate in the survey via email. Up to two reminder e-mails were sent until the desired number of 10 responses was received in each deanery. One person declined to complete the questionnaire and there was no response from a further 19, giving an overall response rate of 83%.

Statistical analysis

An annual surgical rate was calculated for each surgical procedure—the total number of each surgical procedure performed divided by the number of OST years completed.

Data were analysed using STATA statistics/data analysis software (StataCorp 2000, Release V.6. College Station, Texas, USA). Analysis of variance testing between groups was initially performed and when significant, two-sample t tests were conducted, with p values as reported. The significance level was set to p<0.05.

Results

The majority of trainees included in our survey were in the second half of their 7 year OST programme, with no significant difference between deaneries. The North Western Deanery had significantly greater postgraduate experience, with 70% having completed their postgraduate ophthalmology examinations. The majority of trainees surveyed were men. Those training in London were mostly London graduates, and none graduated from outside the UK. All those surveyed from the West Midlands Deanery were also UK graduates, but 20% of those from the North Western Deanery were overseas graduates (table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of respondents

| London south | London north | West Midlands | North western | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of OST mean±SD | 3.8±0.79 | 3.9±1.20 | 4.2 ±1.03 | 4.8±1.62 | 4.18±1.22 |

| Years of postgraduation mean±SD | 6.3±1.25 | 7.1±2.51 | 6.9 ±1.52 | 9.5±2.4 1 p=0.0005 |

7.45±2.29 |

| MRCOphth\FRCOphth completed (%) | 20 | 40 | 40 | 70 | 42.5 |

| Gender | |||||

| Male (%) | 80 | 60 | 60 | 50 | 62.5 |

| Female (%) | 20 | 40 | 40 | 50 | 37.5 |

| Graduated from the same deanery (%) | 60 | 60 | 20 | 30 | 42.5 |

| Graduated from overseas (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 5 |

Data represent mean±SD. p values are for t-test versus overall mean.

MRCOphth, Membership of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists; FRCOphth, Fellowship of the Royal College of Ophthalmologists; OST, ophthalmic specialty training.

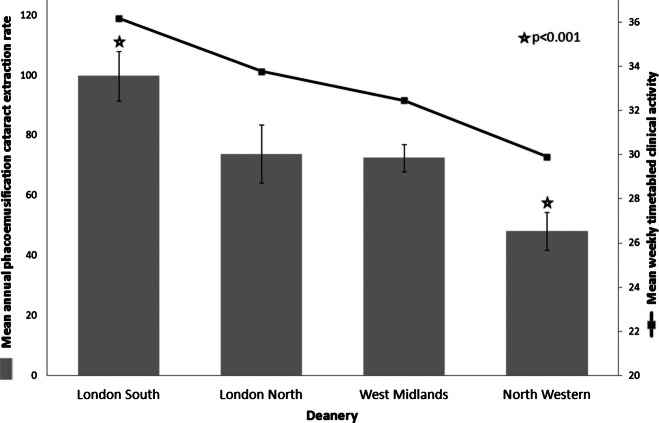

There was significant variation in the annual average phacoemulsification rate between deaneries. The trainees in South Thames were performing almost 100 /year, significantly more than the average and over double compared with those in the North Western Deanery, who were performing significantly less than average (figure 1). Across all regions, extracapsular cataract extraction (ECCE, an alternative technique of cataract extraction that can be useful for complex cases and for phacoemulsification cataract extractions which have become complicated intraoperatively) and anterior vitrectomy (an additional procedure required to deal with vitreous loss into the anterior chamber, the most common complication encountered with phacoemulsification cataract extractions) rates were extremely low, with minimal numbers of complex cases being performed. In total, 72.5% of those surveyed had never performed ECCE and 22.5% had never performed an anterior vitrectomy. This is reflected in only 40% having any confidence in dealing with vitreous loss (table 4).

Figure 1.

Comparison of annual cataract phacoemulsification rate of trainees in different deaneries.

Table 4.

Annual average surgical rates of trainees between deaneries for phacoemulsification and cataract-related operations and other surgical procedures

| Rates per year: | London south | London north | West Midlands | North western | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phacoemulsification | 99.69±26.16 p=0.0005 |

73.83±30.71 | 72.49±14.39 | 48.08±19.72 p=0.0008 |

73.52±29.24 |

| Extracapsular cataract extraction | 0.25±0.43 | 0.10±0.32 | 0.03±0.11 | 0.28±0.35 | 0.16±0.33 |

| Anterior vitrectomies | 0.88±0.76 | 0.95±0.81 | 0.41±0.43 | 0.64±0.64 | 0.72±0.68 |

| Complex cases | 7.47±6.55 | 6.03±3.62 | 4.53±2.42 | 2.80±2.83 | 5.21±4.38 |

| Confident or very confident dealing with vitreous loss (%) | 40 | 40 | 30 | 50 | 40 |

| Trabeculectomies | 1.65±1.91 p<0.0001 |

0.04±0.08 | 0.12±0.20 | 0.05±0.11 | 0.47±1.16 |

| Squint operations | 3.76±3.40 | 2.57±1.60 | 4.38±3.09 | 3.46±2.97 | 3.54±2.82 |

| Lid lacerations | 1.26±1.05 | 1.04±1.22 | 1.35±1.07 | 2.24±1.47 | 1.47±1.26 |

| Corneal lacerations | 0.29±0.40 | 0.15±0.26 | 0.31±0.32 | 0.42±0.51 | 0.29±0.38 |

| Globe ruptures | 0.17±0.19 | 0.12±0.17 | 0.18±0.28 | 0.16±0.28 | 0.16±0.23 |

Data represent the mean number of operations per year±SD. p Values are for t-test versus overall mean.

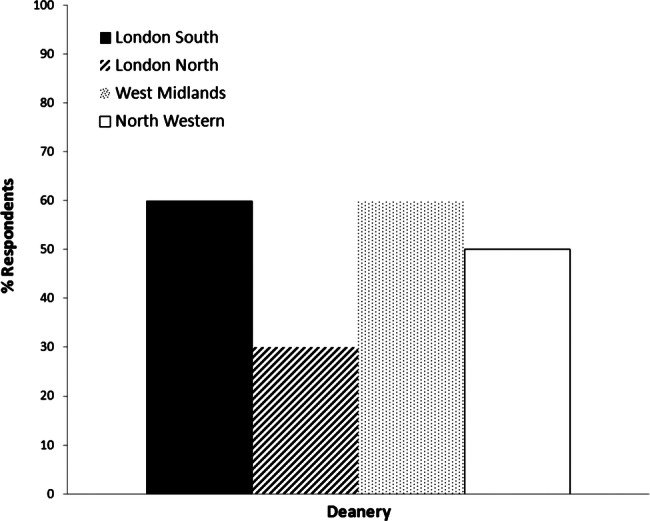

The overall annual average surgical rate for other common eye operations was negligible, with London South trainees performing significantly more trabeculectomy surgery than average, but still low numbers. The surgical rate for emergency eye operations required for dealing with ocular trauma was universally low with 42.5% yet to suture a corneal laceration and 60% never having repaired a ruptured globe (table 4). Only 50% of those surveyed felt that the current training programme would sufficiently prepare them surgically (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of respondents who thought they would be adequately prepared surgically by the end of their training.

The training programme delivery was similar in all the deaneries surveyed with adherence to the Royal College of Ophthalmologists recommendations. This comprised seven sessions/week of work-based experiential learning (direct clinical sessions), two sessions/week of independent self-directed learning and one session/week of local postgraduate teaching. There were differences in the total average number of weekly hours timetabled and direct clinical activity, owing to the varying on-call arrangements. These ranged from 1 in 6 days to 1 in 11 days as non-resident on call. A compulsory compensatory day of rest following on calls, which was only implemented at the main teaching unit in the North Western Deanery, meant that their weekly working hours were effectively reduced by almost 10% (table 5).

Table 5.

Training programme delivery between deaneries

| London south | London north | West Midlands | North western | Overall | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct clinical sessions/week | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 |

| Self-directed learning sessions/week | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Postgraduate teaching sessions/week | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| On-call commitment | 1 in 6 24 h Non-resident |

1 in 7* evenings+24 h Non-resident |

1 in 11 24 h Non-resident |

1 in 11 24 h Non-resident |

|

| Compensatory rest | Nil | Nil | Nil | Day off after on call (3.63 h/week) | |

| Adjusted total hours/week† | 48.17 | 45.77 | 44.85 | 40.82 | 44.90 |

| Adjusted direct clinical hours/week† | 36.17 | 33.77 | 32.45 | 29.91 | 33.08 |

*On-call commitments for trainees in year 5 or above of specialty training. Trainees below year 5 of specialty training did a resident on-call and worked similar total and direct clinical hours.

†Number of hours worked based on 4 h/session, 5 h per weekday non-resident on-call and 10 h per weekend non-resident on-call, adjusted for any compensatory rest. Direct clinical hours included direct clinical sessions plus on-call commitment.

Discussion

The adequacy of postgraduate surgical training in the UK remains a perpetual debate. This paper is the first to report the surgical progress of doctors training under the new OST programme and also the first to describe regional variations in surgical training experience.

Our data indicate that the average annual rate of phacoemulsification should be sufficient to reach the minimum required for completion of specialist training among all regions surveyed. Interestingly, the arbitrary value of 300 covers 7 years of OST, compared with the equivalent value required within four and a half years under the previous training system. Those training outside London may fall short of what has been the national average cumulative cataract experience at the end of training for almost 20 years (500–600 cases).9 This is not surprising as it has been estimated that UK surgical trainees worked 30 000 h before becoming a consultant under the previous training system.10 11 This is considerably less than the 1096 days (less than 9000 h) of work-based experiential learning the over 7 year OST programme in which the Royal College of Ophthalmologists expects it will be possible for trainees to achieve the minimum surgical procedures and sufficient experience in clinical ophthalmology.8 This, however, still compares favourably with the shorter training ophthalmologists undergo in other well-respected countries.12

While surgical ability is not solely determined by the number of operations performed, it has been clearly demonstrated that the grade of the surgeon influences the rate of complications.13 14 The OST curriculum, in common with equivalent curriculums in other surgical specialties, assesses for minimal competence and not ability. There is therefore no further stipulation regarding the case mix of operations or managing complications. It is worrying, however, that there is the potential for doctors to progress through OST without having performed operations required to deal with the most common complication of cataract surgery (ie, an anterior vitrectomy and ECCE) as was currently the situation for 77.5% of those we surveyed. We expect, however, that any such surgical deficiencies will be identified by the annual review and appraisal system that all trainees in the UK are required to attend.

With regard to other surgery that was previously commonly performed by trainees, we found a continuation of the decline in trabeculectomy and squint procedures. This is undoubtedly due to the increasingly subspecialist nature of ophthalmology practice in the UK, as well as the increasing operations performed by doctors undertaking subspecialist fellowships. At their current rate, trainees are again likely to fall short of the numbers that doctors who completed their training only 3 years previously under the previous training system achieved.9 It could be argued that the OST programme is designed to only produce general ophthalmologists with subspecialist training achieved though fellowships. However, the lack of experience gained in dealing with ocular trauma that our study has identified is a matter of concern. These are important skills required by all practising consultant ophthalmologists, but there is no minimum number required for completion of training, with 42.5% of those surveyed never having sutured a corneal laceration and 60% never having repaired a globe rupture. The OST programme may place too much emphasis on gaining numbers of routine cataract operations, at the expense of other surgery.

The most striking finding is the previously unreported large regional variation in the annual rate of phacoemulsification cataract surgery being performed by trainees. This result is difficult to explain, but the number of operations performed during the training programme will be influenced both by the opportunities for surgical training as well as the surgical aptitude of individual trainees.

With regard to surgical opportunity, it was previously reported that trainees gained more surgical experience at district general hospitals (DGHs) than at teaching hospitals.15 It could be that the greater number of DGHs in the South Thames Deanery together with multiple established teaching hospitals gives the best balance for opportunities in surgical training. There is also the longstanding issue for all junior doctors in training, of service provision versus training needs within the NHS, and this was certainly identified as a problem among those training in ophthalmology under the previous system.16 It is an issue that is likely to worsen with reduced budgets and greater efficiency targets affecting the NHS. There is the additional impact of independent sector treatment centres17 and, more specific to ophthalmology, visual acuity thresholds that primary care trusts are increasingly imposing, which may further reduce the already low proportion of cases within NHS hospitals that are suitable for junior trainees.15 The effect of this may differ considerably throughout the country.

The time lost to training as a result of the EWTD may also contribute to regional variations in surgical experience despite a national curriculum from the Royal College. It may not be a coincidence that timetabled clinical activity directly correlated with the annual phacoemulsification rate. The compensatory rest day after on calls implemented in the main teaching unit in the North Western Deanery amounts to 33 working weeks throughout the OST programme. The EWTD was introduced in 1998, with the most relevant requirements being a limit on average weekly working time to 48 h, with 11 h of continuous rest in every 24 h period.18 At present, any individual can opt out of the working-hours element by voluntarily signing a waiver. Individuals cannot, however, opt out of the requirement for rest and the compensatory rest day is therefore enforced by some trusts, and doctors may not be legally insured to work if they undertake clinical duties during this period. The EWTD is less explicit when regarding non-resident on-call commitments, as is the case with most ophthalmology on calls, and it is interesting how this has been interpreted in different deaneries.

It is unlikely that a significant difference in surgical aptitude between trainees from different regions is the root cause of the regional variation in cataract numbers. Changes implemented by MMC mean that doctors now enter OST with little or no surgical experience and there is also limited or no assessment of surgical skill at the interview process, with the emphasis being on academic achievement. The use of virtual reality surgical simulators has been piloted as a tool for selection and shows promise in training as well as assessment.19 This, together with objective structured assessments of cataract surgical skill based on intraoperative video analysis, may offer some resolution in maximising learning from the decreased surgical time available to trainees.20

This study is limited by reliance on self-reported data. The sample also included only four deaneries; however, these large deaneries represent nearly 50% of all ophthalmology trainees in the UK, and the number of respondents to the survey represents approximately 50% of those eligible to answer the survey.3 In addition, as the mean year of training of the respondents in this study was year 4 of 7, we do not know how much further experience trainees will get in the latter years of their training. Nevertheless, we feel that these data raise valid questions about the standardisation of OST within the UK, especially as recruitment for consultant jobs at the end of OST is at the national level rather than at the deanery level. The only currently available data that allow objective comparison of the different deaneries are application competition ratios and trainee satisfaction results from the General Medical Council national training surveys, which seem to show little correlation to our findings from this study.21 22

More investigation is warranted to corroborate these regional variations in surgical training and to identify the reasons behind them. Although training programmes within the UK are different, they share more similarities and regulations in comparison to others throughout the world.12 There is concern, however, that the new OST programme may be providing less opportunity for surgical training than the previous system and this is reflected by the fact that only half the doctors surveyed felt they would be adequately prepared at the end of their training. It is very likely that there are similar issues of reduced surgical numbers and regional variation of training in other surgical specialties which have also undergone reform following MMC. Sharing the strengths from different deaneries and combining them would enable improvements in OST training and help overcome constraints placed by EWTD and an evolving NHS and would ensure that the future care of our patients is not compromised due to lack of training.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all our colleague ophthalmology trainees who took the time to complete the questionnaire.

Footnotes

Contributors: The six authors are justifiably credited with authorship, according to the authorship criteria. IASR contributed to the conception, design, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript before he finally approved it. RJS was responsible for the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, and finally approved the manuscript. ST and AS contributed to the acquisition of data and critical revision of the manuscript before finally approving it. GB contributed to the conception, design and critical revision of the manuscript before finally approving it. WHC contributed to theconception, design and drafting of the manuscript before finally approving it.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: Presented as a poster presentation at the Royal College of Ophthalmologists Annual Conference, Liverpool UK, May 2012.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the DOI: 10.5061/dryad.78bf7.

References

- 1.Medical specialty training (England) About modernising medical careers. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4079530 (accessed 9 Jan 2013).

- 2.Department of Health The European Working Time Directive for trainee doctors—Implementation update. London: Department of Health, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Royal College of Ophthalmologists Ophthalmic Directory. http://www.rcophth.ac.uk/page.asp?section=159§ionTitle=Ophthalmic+Directory (accessed 9 Jan 2013).

- 4.The Royal College of Ophthalmologists Curriculum summary table. http://curriculum.rcophth.ac.uk/summary-table/summary-table (accessed 9 Jan 2013).

- 5.The Royal College of Ophthalmologists Surgical logbook guidance. Education and training department. http://www.rcophth.ac.uk/core/core_picker/download.asp?id=619&filetitle=Logbook+Information+December+2008/ (accessed 9 Jan 2013).

- 6.The Royal College of Ophthalmologists Curriculum of higher specialist training in ophthalmology. http://www.rcophth.ac.uk/core/core_picker/download.asp?id=396/ (accessed 9 Jan 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lynn E. Poll highlights frustration with changes in UK medical training. BMJ News 2007;335:174 [Google Scholar]

- 8.The Royal College of Ophthalmologists Programme delivery. http://curriculum.rcophth.ac.uk/programme-delivery/ (accessed 9 Jan 2013).

- 9.Ezra DG, Changra A, Okhravi N, et al. Higher surgical training in ophthalmology: trends in cumulative surgical experience 1993–2008. Eye 2010;24:1466–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Department of Health Unfinished business: proposals for reform of the senior house officer grade-a paper for consultation. London: Department of Health, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phillip H, Fleet Z, Bowman K. The European Working Time Directive-Interim Report and Guidance from the Royal College of Surgeons of England Working Party. London: Royal College of Surgeons, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan W, Saedon H, Falcon MG. Postgraduate ophthalmic training: how do we compare? Eye 2011;25:965–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnston RL, Taylor H, Smith R, et al. The Cataract National Dataset electronic multi-centre audit of 55 567 operations: variation in posterior capsule rupture rates between surgeons. Eye 2010;24:888–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchan JC, Cassels-Brown A. Determinants of cataract surgical experience and opportunities and complication rates in UK higher specialist training. Eye 2008;22:1425–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aslam SA, Elliott AJ. Cataract surgery for junior ophthalmologists: are there enough cases? Eye 2007;21:799–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibson A, Boulton MG, Watson MP, et al. The first cut is the deepest: basic surgical training in ophthalmology. Eye 2005;19:1264–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Au L, Saha K, Fernando B, et al. ‘Fast-track’ cataract services and diagnostic and treatment centre: impact on surgical training. Eye 2008;22:55–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.1993. Council directive 93/104/EC of 23 November 1993 concerning certain aspects of the organisation of working time. Council of the European Union.

- 19.Spiteri A, Aggarwal R, Kersey T, et al. Phacoemulsification skills training and assessment. Br J Ophthalmol 2010;94:536–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saleh GM, Gauba V, Mitra A, et al. Objective structure assessment of surgical skill. Arch Ophthalmol 2007;125:363–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.General Medical Council National training surveys. http://reports.pmetbtrainingsurveys.org/GroupCluster.aspx?agg=AGG28|2010 (accessed 9 Jan 2013). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medical specialty training (England) Competition information 2011. http://www.mmc.nhs.uk/specialty_training/specialty_training_2011_final/recruitment_process/stage_2_-_choosing_your_specia/competition_information.aspx (accessed 9 Jan 2013).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.