Abstract

Objectives

Surgery duration is a source of preoperative anxiety for patients undergoing cataract surgery. To better inform patients, we evaluated the agreement between objective and patient-perceived surgery durations.

Design

Case series.

Setting

Public teaching university hospital (Paris, France).

Participants

During the study period, 368 cataract surgery cases performed on 285 patients were included, 85 cases were excluded from the final analysis. All patients who had uneventful phacoemulsification were included. Cases with any significant intraoperative adverse event or cases requiring additional anaesthesia other than topical were excluded. Resident performed cases were also excluded.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Procedures were timed (objective duration) and patients were asked, immediately afterwards, to assess the duration of their surgery (patient-assessed duration). The agreement between objective and patient-assessed durations as well as influencing factors was studied.

Results

Mean objective duration (13.9±5 min) and patient-assessed duration (15.3±6.9 min) were significantly correlated (Spearman's r=0.452, p<0.0001). Furthermore, Bland-Altman analysis and the intraclass correlation coefficient (0.341, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.44) were quite in agreement. On univariate analysis, senior-performed procedures were significantly shorter than those performed by juniors (13.4 vs 17.8 min, p=0.0001). Pain was recorded as ‘no sensation’ (31.5% of the cases), ‘mild sensation’ (41%), ‘moderate pain’ (23.3%), ‘intense pain’ (3.5%) and ‘unbearable pain’ (0.7%). Groups with high pain score had significantly longer procedures (p<0.001). Multivariate analysis revealed that the only independent factors associated with both the objective and patient-assessed durations of surgery were surgeon's experience and pain-score.

Conclusions

In our study, patients’ estimated and real duration of the surgery showed moderate agreement, suggesting that emotions associated with eye surgery under topical anaesthesia did not dramatically hinder the patients’ perception of time. However, the benefit of preoperative counselling regarding the duration of surgery will need further evaluation.

Keywords: Medical Education, Treatment Surgery

Article summary.

Article focus

Modern cataract surgery is a safe and quick procedure. Nonetheless, it remains a stressful event from the patients’ standpoint.

Several factors have been recognised to participate in the patients’ preoperative anxiety and targeted preoperative counselling has been shown to be of value.

Though cataract surgery duration is a frequent patient preoperative qualm, it has not been properly studied and the patient's perception of time is largely unknown.

Key messages

Patients’ perceived cataract surgery duration is reasonably accurate, whatever be the circumstances.

Surgeons’ experience and pain perception were the two factors independently associated with surgery duration.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The large studied population and the strict definition used for operative time provide reliable measurements of the surgery duration whether objective or patient perceived.

Anxiety status, chronic illnesses, systemic medications were not part of our standardised study protocol. Moreover, all our patients were on sedative medications at the time of surgery. This might have affected patients’ perceptions.

The benefit in terms of patient comfort/satisfaction of preoperative information regarding surgery duration needs specific studies beyond the scope of the present report.

Introduction

The shortened duration of cataract surgery is one of the striking features owing to the improvement of surgical techniques. Live surgery events and real-time surgical video recordings by elite surgeons nowadays seldom show procedures lasting more than 10 min. The quickness of modern cataract surgery by phacoemulsification has made topical anaesthesia, the effects of which wear off faster than the previously used peribulbar injections, the method of choice for analgesia.1 Nevertheless, whatever the amount of trust patients put on their surgeon, many remain apprehensive of eye surgery under full consciousness or with minimal sedation by systemic administration of drugs. This apprehension is often focused on the fear of involuntary eye movements during the procedure, which may complicate the surgeon's task, on patients’ fear of seeing their eye surgery or on the fear of painful sensations. In reply, quite abundant data are now available stemming from several studies focused on the impressions of patients during the procedures.2 3 Various methods to assess the perception of pain have been used and have validated that cataract surgery under topical anaesthesia is by and large usually a painless procedure.4 Visual sensations experienced by patients under the operating microscope have also been recorded and have mostly been found to be of no concern.5 6 In addition to these topics, patients prior to their surgery have frequent qualms regarding the duration of the procedure and hence regarding their ability to withstand their eye surgery under topical anaesthesia.7 Providing additional targeted information to patients undergoing cataract surgery has been shown to improve their satisfaction.8

This information could include data regarding the duration of the procedure. However, surprisingly, in contrast to the common nature of cataract surgery by modern phacoemulsification, there are scarce data regarding its duration. The purpose of this study was therefore to compare the objective duration of cataract surgery with the patients’ subjective assessment of this duration.

Methods

The study was set in the Department of Ophthalmology of Hôpital Cochin, a teaching university hospital located in Paris, France. Data were collected prospectively from consecutive patients operated between 17 May 2011 and 22 July 2011, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

All patients who had uneventful phacoemulsification under topical anaesthesia with the placement of an intraocular lens in the capsular bag were included. Cases with any ‘significant adverse event’ defined either by a major intraoperative complication such as vitreous loss or by a technical problem such as phacoemulsifier malfunction that prolonged the procedure by 10 min or more were excluded. Similarly, patients who required any anaesthesia in addition to topical lidocaine 2% gel or those who required sedation in addition to the preoperatively given hydroxyzine were excluded from the analyses. Teaching cases involving resident participation were also excluded from the analyses. The duration of the procedure, referred throughout the text as the objective duration, was timed by operating room nurses as the exposure of the patients’ eye to the light of the operating microscope, from the beginning until the end of the surgery.

The objective duration of surgery was compared to its subjective assessment obtained by questioning patients immediately after drape removal and referred throughout the text as the patient-assessed duration. If the initial patients’ replies were imprecise, a second line of questioning was used requesting patients to assess the duration of their surgery in minutes. To avoid assessment biases, the patients were not warned before the surgery that they would be asked to assess the duration of their procedure.

The patients’ perception of pain during surgery was also assessed with a standard numeric scale, graded from 0 to 4: 0 (no pain), 1 (mild sensation), 2 (moderate pain), 3 (intense pain) and 4 (unbearable pain) as previously used in other studies.4 9 10

Other factors were also recorded: age, gender, first or second eye surgery and best corrected preoperative visual acuity. All surgeries were performed between 8:00 and 14:00 and the patients were requested to fast from midnight on the day prior to their surgery. The patients’ preoperative schedules were recorded: duration of fasting, time interval between wake up and surgery, time interval between entry in the department suite and surgery (waiting time in the department). All patients received 0.5 mg/kg of hydroxyzine at their time of arrival in our department, which was used as sedative and for additive sedation during the surgery when necessary. No other drug was given preoperatively, including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The need for additional anaesthetic techniques was recorded.

Surgeons were categorised as seniors when they had the experience of more than 1000 procedures performed prior to the study or as juniors otherwise.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as numbers (percentages) and comparisons were conducted using the Fisher's exact test. For continuous variables, mean±SD or median (IQR) are provided, and comparisons were conducted using the Kruskal-Wallis test or Student's t test.

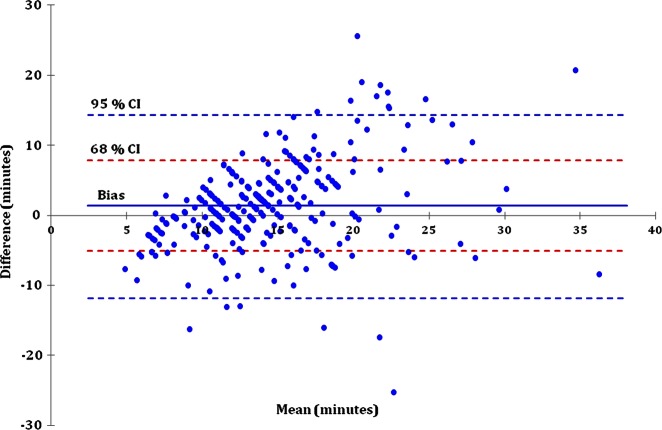

To evaluate the agreement between objective and patient-assessed durations, a Bland-Altman plot was used.11 The differences between the two methods (ie, objective and patient-assessed durations) are plotted against their mean. The Bland-Altman analysis provides the mean difference (also called bias) as well as the 95% or the 68% limits of agreement corresponding, respectively, to the mean difference ±2 or ±1 SD. When agreement between the two methods is good, most of the differences should reside within the agreement limit interval. We also computed the intraclass correlation coefficient to quantitatively evaluate the agreement.

Correlation tests were conducted using the Spearman's correlation coefficient (r). Factors with p<0.10 in the univariate analysis were included in a multivariate linear regression and analysis of covariance model to determine the independent factors associated with either objective or patient-assessed surgery durations. p Values <0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were performed with XLSTAT V.2012.2.02 software (Addinsoft, Paris, France).

Results

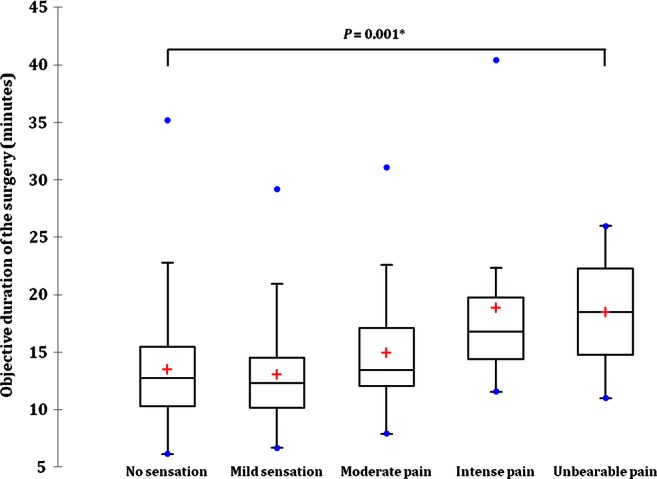

A total of 283 cases performed in 218 patients were analysed after the exclusion of 85 cases (65 patients) which met one or more exclusion criteria as detailed herein. Resident participation was the most frequent motive for exclusion (70 cases). Other causes were significant intraoperative adverse events including posterior capsular break or zonular disinsertion (8 cases) and phacoemulsifier breakdown (1 case). Four out of the eight cases presenting intraoperative vitreous loss had an identifiable risk factor for this complication: two were traumatic cataracts and two were cataracts related to severe pseudoexfoliation syndrome. Thirteen cases required additional anaesthesia or sedation including sub-Tenon's block (5 cases), subconjunctival injection (1 case), intracameral injection of lidocaine (1 case) and/or midazolam intravenous sedation (6 cases). Characteristics of the study population, patients’ schedule on the day of surgery, sequence of procedures, phacoemulsifiers used and surgery duration are shown in table 1. No sensation was reported in 106 (31.5%) cases, a mild sensation in 147 (41%) cases, moderate pain in 90 (23.3%) cases, intense pain in 14 (3.5%) cases and unbearable pain in 2 (0.7%) cases. The perception of pain did not significantly differ between the first and the second eye procedures. Out of 155 patients operated in their first eye, 113 patients (73%) reported low pain (no or mild sensation (score 0 or 1)), while 92 out of 128 patients (72%) operated on their second eye rated their sensations similarly (p=0.9).

Table 1.

Patient population, preoperative schedule and surgical procedures

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 218 |

| Cataract surgery cases (n) | 283 |

| Age (mean years (±SD)) | 73.2 (±9.3) |

| Gender (cases, n (%)) | |

| Male | 132 (46.6%) |

| Female | 151 (53.4%) |

| Preoperative visual acuity (mean LogMAR (±SD)) | 0.4 (±0.2) |

| Schedule on the day of surgery (hours) | |

| Fasting time, mean (±SD) | 14 (±1.8) |

| Time interval between wake up and surgery, mean (±SD) | 4.6 (±1.2) |

| Waiting time in the department, mean (±SD) | 2.3 (±0.7) |

| Sequence of surgery (cases, n (%)) | |

| First eye | 155 (54.8%) |

| Second eye | 128 (45.2%) |

| Surgeons’ experience (cases, n (%)) | |

| Senior | 253 (89.4%) |

| Junior | 30 (10.6%) |

| Pain assessment | |

| Low pain score | 205 (72.4%) |

| High pain score | 78 (27.6%) |

Comparison between objective and patient-assessed durations

The mean objective surgery duration was 13.9 (±5) min and the mean patient-assessed duration was 15.3 (±6.9) min. Bland-Altman plot showed a fair agreement between the objective and patient-assessed durations (figure 1). Mean difference (or bias) was only 1.4 min (95% CI 0.63 to 2.15 min). However, an agreement worsening was noted for longer procedures, but the error was equally distributed over and under the limits of agreement (−11.3 to 14.1 min). Intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.341 (95% CI 0.23 to 0.44), suggesting a moderate agreement between the objective and patient-assessed durations.

Figure 1.

Bland-Altman plot between the objective and patient-assessed surgery durations. The solid line indicates the mean difference (or bias); the blue and red dash lines indicate the 95% and 68% limits of the agreement, respectively.

A significant correlation between the objective and patient-assessed durations of the surgery was observed (Spearman's r=0.452, p<0.0001).

Factors associated with objective surgery duration

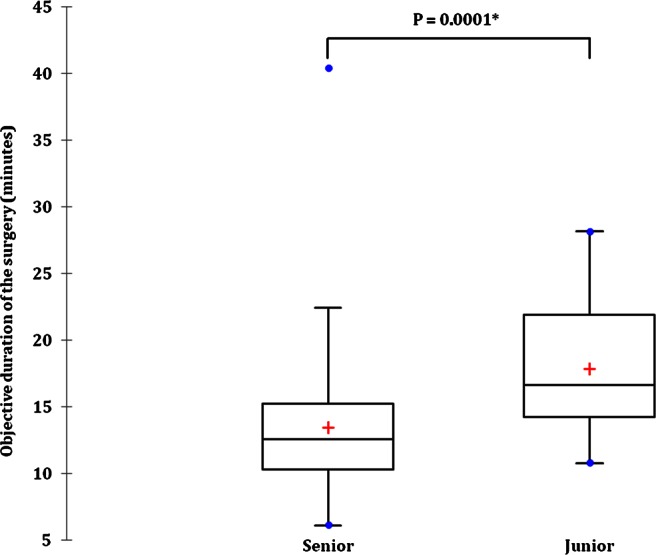

On univariate analysis, objective surgery duration was significantly correlated to preoperative VA (p=0.001), time interval between wake up and surgery (p=0.041) and to the waiting time in the department (p=0.006). The corresponding regression coefficients and 95% CI are provided in table 2. Similarly, objective duration was significantly different according to surgeon experience with shorter procedures for seniors (13.4±4.8 min) compared to juniors (17.8±4.7; figure 2). The objective duration was significantly different according to pain score group with significantly longer procedures in groups with high pain scores (scores 4, 3 and 2) compared to groups with low pain scores (score 0 or 1) with mean surgery durations of 15.5 (±5.7) and 13.2 (±4.5), respectively (figure 3). The objective duration was significantly different between the first and the second eye procedures, but not according to the gender (table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate analyses of factors associated with surgery duration

| Objective surgery duration |

Patient-assessed surgery duration |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Regression coefficient (95% CI) or mean (±SD) | p Value* | Regression coefficient (95% CI) or mean (±SD) | p Value* |

| Age | 0.02 (−0.04 to 0.86) | 0.469 | 0.11 (0.03 to 0.2) | 0.011 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 14.2 (±5.2) | 0.317 | 15.8 (±6.2) | 0.184 |

| Female | 13.6 (±4.8) | 14.8 (±7.4) | ||

| Preoperative visual acuity | 4.23 (1.75 to 6.72) | 0.001 | 0 (−3.5 to 3.5) | 1.00 |

| Schedule on the day of surgery | ||||

| Fasting time | 0.27 (−0.04 to 0.59) | 0.091 | 0.16 (−0.28 to 0.60) | 0.477 |

| Time interval between wake up and surgery | 0.49 (0.02 to 0.95) | 0.041 | 0.71 (0.07 to 1.36) | 0.03 |

| Waiting time in the department | 1.15 (0.34 to 1.96) | 0.006 | 1.05 (−0.07 to 2.17) | 0.066 |

| Sequence of surgery | ||||

| First eye | 14.1 (±5.4) | 0.036 | 15.1 (±6.8) | 0.632 |

| Second eye | 13.6 (±4.4) | 15.5 (±7.0) | ||

| Surgeons’ experience | ||||

| Senior | 13.4 (±4.8) | <0.0001 | 15.0 (±6.7) | 0.032 |

| Junior | 17.8 (±4.7) | 17.8 (±7.4) | ||

| Pain assessment | ||||

| Low pain score | 13.2 (±4.5) | 0.001 | 14.4 (±6.5) | <0.001 |

| High pain score | 15.5 (±5.7) | 17.6 (±7.3) | ||

*Linear regression for correlation tests and Student's t-test for mean comparison.

Figure 2.

Objective surgery duration according to the surgeons’ experience. The bar in the box indicates the median, the cross the mean and the lower and upper hinge the IQR. The whisker extends to the most extreme data point which is no more than 1.5 times the IQR. Dots represent values outside the fences (outliers).*Student's t test.

Figure 3.

Objective surgery duration according to the pain score group. The bar in the box indicates the median, the cross the mean and the lower and upper hinge the IQR. The whisker extends to the most extreme data point which is no more than 1.5 times the IQR. Dots represent values outside the fences (outliers).*Kruskal-Wallis test.

Multivariate analysis revealed patients’ preoperative visual acuity, waiting time in the department, surgeon experience and pain score group to be independent factors associated with objective surgery duration (table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analyses of factors associated with surgery duration

| Objective surgery duration |

Patient-assessed surgery duration |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Adjusted regression coefficient* | 95% CI | p value | Adjusted regression coefficient* | 95% CI | p value |

| Age | – | – | – | 0.1 | 0 to 0.2 | 0.022 |

| Preoperative visual acuity | 3.6 | 1.2 to 5.9 | 0.002 | – | – | – |

| Waiting time in the department | 0.8 | 0.1 to 1.6 | 0.03 | – | – | – |

| Junior vs senior surgeon | 4.1 | 2.4 to 5.9 | 0.0001 | 3.3 | 0.8 to 5.8 | 0.01 |

| Low vs high pain score | −2.3 | −3.5 to −1.1 | 0.0002 | −3.1 | −4.8 to −1.4 | 0.0004 |

*Regression coefficients adjusted for variables with p values <0.10 in the univariate analysis.

Factors associated with patient-assessed surgery duration

On univariate analysis, the patient-assessed surgery duration was correlated to patient age (p=0.011), and time interval between wake up and surgery (p=0.03). The corresponding regression coefficients and 95% CI are provided in table 2. Similarly, the patient-assessed duration was also significantly different according to surgeon experience (p=0.032) and according to pain-score group (p=0.001). Conversely, the patient-assessed duration was not significantly different between the first and the second eye procedures or according to gender.

Multivariate analysis revealed patient age, surgeon experience and pain score group to be independent factors associated with patient-assessed surgery duration (table 3).

Discussion

Our study showed that patients overall fairly estimated the duration of their surgery and that the two independent factors associated with both the objective and subjective surgery durations were the surgeon's experience and pain score.

The objective duration of cataract surgery by modern phacoemulsification has not been the main outcome measure of previous studies, but has occasionally been assessed mainly in analyses of the effects of teaching or as a secondary outcome.12 13 When reported, the duration of surgery ranged from an average of 30 min in studies published in 2003 to 15–19 min in recent reports.14–17 Our objective measure of procedures lasting 13 min is in line with this shortening that most probably stems from improvements in the technique of cataract surgery, including suture-less clear corneal microincisions. As shown previously, our data confirmed that experienced surgeons are quicker than more junior ophthalmologists.12 13 In our study, the surgeon's experience factor was independently associated with both the objective and subjective surgery durations.

The subjective perception of time by patients undergoing cataract surgery under topical anaesthesia has never been studied either. Preparations for surgery include the testing of phacoemulsifiers, applying topical anaesthesia, preoperative disinfection of the eye by povidone-iodine, draping and placement of a lid speculum. These steps may take as long as the surgical procedure itself or, in some instances, longer than the surgery. From the patients’ perspective, distinguishing these preoperative stages from their surgery per se may be difficult. To minimise this bias when seeking our patients’ subjective assessment of the duration of their surgery, we specifically asked for their impression of the elapsed time between the illuminations of their eye under the operating microscope until the removal of the drapes. However, this time interval both subjectively assessed and clocked by nurses may have added approximately 1 or 2 extra minutes to the real time of the surgery, as the surgeons adjusted the focus of the microscope and made their final preparations for the procedure.

The assessment of pain was a secondary outcome measure in our study and we used the simple five-step scale as validated in other studies.4 9 10 A lack of sensation or a mild sensation was reported in 72.4% of cases, moderate pain in 23.3% cases and intense or even unbearable pain in 4.3% of cases. These percentages are comparable to the previous reports using the same five-step pain score scale.9 Unsurprisingly, the perception of pain was correlated with the duration of procedures. In our study, the pain-score group was independently associated with both the objective and subjective surgery durations. In a previous study, the patients tended to report their second eye surgery as more painful than their first eye surgery and this finding was related to a decreased preoperative anxiety at the time of the second procedure.16 However, this finding was not observed in our study, nor in another recent report.18 This discrepancy could be due to the preoperative sedation given to all our patients. Such medications can alter the perception of pain as well as the perception of duration and also aim at reducing anxiety. Similarly, we did not account for the patients’ systemic medications or illnesses, if any, which could also have altered their judgement and their pain thresholds.

Preoperative standardised grading of cataracts or pupil size was not recorded in our study. The patient's age may, however, be used as a surrogate parameter influencing the grade of the cataract.19 20 In nuclear cataracts, preoperative visual acuity may also be correlated to its grade.21 Our data confirmed that the objective duration of the surgery was longer in cases with worse preoperative visual acuity, as more advanced cataracts require a longer duration of ultrasonic power release.22 Surprisingly, the age of the patient was not correlated with objective surgery duration, but with patient-assessed surgery duration, though weakly. The chop technique may result in quicker procedures; however, the evaluation of the effect of surgical techniques on the duration of surgery was not within the scope of our study.23

Most patients quite correctly assessed the duration of their surgery, though the correlation with objective surgery duration was only moderate and the samples were large. Hence, we were not able to identify specific characteristics significantly associated with an underestimation or an overestimation of time. Although evidence suggests that fasting prior to cataract surgery under topical anaesthesia can be abandoned, in this series, the patients fasted from midnight on the day prior to their surgery.24 As our patients were operated from 8:00 to 14:00, the fasting time varied from one case to another, but these variations did not influence the subjective assessment of the duration of surgery. Similarly, we thought that an early arrival and a subsequent long waiting in the Department of Ophthalmology prior to entry in the operating room could be a factor of stress resulting in an overassessment of the duration of their surgery by patients. Yet, our analysis did not reveal that this factor played any role. We unexpectedly observed that the time interval between wake up and surgery, as well as the waiting time in the department, was associated with longer procedures. This might have been linked to surgeons slowing down after a number of cases. Although it has been suggested that handholding may reduce anxiety and the perception of pain during cataract surgery, this was not applied in our practice.25

Our study showed that the patients overall fairly estimated the duration of their surgery. The trend in the past decades has been towards a constant reduction of the duration of procedures in eye surgery. As new technical improvements are under way, such as femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery, the fact that patients are rather acutely aware of the duration of procedures must be taken into consideration as an important parameter for their comfort. However, proving the benefit of preoperative counselling in terms of patient satisfaction would require a specific study beyond the scope of this report.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Jean-Baptiste Daudin, MD and Dominique Monnet MD, PhD provided and cared for study patients.

Footnotes

Contributors: P-RR, BLD, CT and APB participated in conception and design, acquisition of the data, and analysis and interpretation of data. SG substantially participated conception and design, and analysis and interpretation of the data. OR was involved in conception and design, and acquisition of the data. All authors have contributed to drafting the article and revising it critically for important intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The study was supported by the Association d'Ophtalmologie de Cochin, Paris, France.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Institutional Board Review of Cochin hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi:10.5061/dryad.27sk4

References

- 1.Leaming DV. Practice styles and preferences of ASCRS members—2003 survey. J Cataract Refract Surg 2004;30:892–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fagerstrom R. Fear of a cataract operation in aged persons. Psychol Rep 1993;72:1339–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nijkamp MD, Kenens CA, Dijker AJ, et al. Determinants of surgery related anxiety in cataract patients. Br J Ophthalmol 2004;88:1310–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davison M, Padroni S, Bunce C, et al. Sub-Tenon's anaesthesia versus topical anaesthesia for cataract surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(3):CD006291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newman DK. Visual experience during phacoemulsification cataract surgery under topical anaesthesia. Br J Ophthalmol 2000;84:13–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yaylali V, Yildirim C, Tatlipinar S, et al. Subjective visual experience and pain level during phacoemulsification and intraocular lens implantation under topical anesthesia. Ophthalmologica 2003;217:413–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nijkamp MD, Ruiter RA, Roeling M, et al. Factors related to fear in patients undergoing cataract surgery: a qualitative study focusing on factors associated with fear and reassurance among patients who need to undergo cataract surgery. Patient Educ Couns 2002;47:265–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haripriya A, Tan CS, Venkatesh R, et al. Effect of preoperative counseling on fear from visual sensations during phacoemulsification under topical anesthesia. J Cataract Refract Surg 2011;37:814–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vielpeau I, Billotte C, Kreidie J, et al. Comparative study between topical anesthesia and sub-Tenon's capsule anesthesia for cataract surgery. J Fr Ophtalmol 1999;22:48–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roman S, Auclin F, Ullern M. Topical versus peribulbar anesthesia in cataract surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 1996;22:1121–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986;1:307–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosler MR, Scott IU, Kunselman AR, et al. Impact of resident participation in cataract surgery on operative time and cost. Ophthalmology 2012;119:95–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wiggins MN, Warner DB. Resident physician operative times during cataract surgery. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging 2010;41:518–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tranos PG, Wickremasinghe SS, Sinclair N, et al. Visual perception during phacoemulsification cataract surgery under topical and regional anaesthesia. Acta Ophthalmol Scand 2003;81:118–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wickremasinghe SS, Tranos PG, Sinclair N, et al. Visual perception during phacoemulsification cataract surgery under subtenons anaesthesia. Eye (London) 2003;17:501–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ursea R, Feng MT, Zhou M, et al. Pain perception in sequential cataract surgery: comparison of first and second procedures. J Cataract Refract Surg 2011;37:1009–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ang CL, Au Eong KG, Lee SS, et al. Patients’ expectation and experience of visual sensations during phacoemulsification under topical anaesthesia. Eye (London) 2007;21:1162–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bardocci A, Ciucci F, Lofoco G, et al. Pain during second eye cataract surgery under topical anesthesia: an intraindividual study. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2011;249:1511–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chylack LT, Jr, Wolfe JK, Singer DM, et al. The Lens Opacities Classification System III. The Longitudinal Study of Cataract Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol 1993;111:831–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Age-Related Eye Disease Study Research G The age-related eye disease study (AREDS) system for classifying cataracts from photographs: AREDS report no. 4. Am J Ophthalmol 2001;131:167–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nangia V, Jonas JB, Sinha A, et al. Visual acuity and associated factors. The Central India Eye and Medical Study. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e22756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nixon DR. Preoperative cataract grading by Scheimpflug imaging and effect on operative fluidics and phacoemulsification energy. J Cataract Refract Surg 2010;36:242–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong T, Hingorani M, Lee V. Phacoemulsification time and power requirements in phaco chop and divide and conquer nucleofractis techniques. J Cataract Refract Surg 2000;26:1374–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanmugasunderam S, Khalfan A. Is fasting required before cataract surgery? A retrospective review. Can J Ophthalmol 2009;44:655–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Modi N, Shaw S, Allman K, et al. Local anaesthetic cataract surgery: factors influencing perception of pain, anxiety and overall satisfaction. J Perioper Pract 2008;18:28–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.