Abstract

Objectives

Early life factors, like intelligence and socioeconomic status (SES), are associated with health outcomes in adulthood. Fitting comprehensive life-course models, we tested (1) the effect of childhood intelligence and SES, education and adulthood SES on psychological distress at midlife, and (2) compared alternative measurement specifications (reflective and formative) of SES.

Design

Prospective cohort study (the Aberdeen Children of the 1950s).

Setting

Aberdeen, Scotland.

Participants

12 500 live-births (6282 boys) between 1950 and 1956, who were followed up in the years 2001–2003 at age 46–51 with a postal questionnaire achieving a response rate of 64% (7183).

Outcome measures

Psychological distress at age 46–51 (questionnaire).

Results

Childhood intelligence and SES and education had indirect effects on psychological distress at midlife, mediated by adult SES. Adult SES was the only variable to have a significant direct effect on psychological distress at midlife; the effect was stronger in men than in women. Alternative measurement specifications of SES (reflective and formative) resulted in greatly different model parameters and fits.

Conclusions

Even though formative operationalisations of SES are theoretically appropriate, SES is better specified as reflective than as a formative latent variable in the context of life-course modelling.

Article summary.

Article focus

Intelligence and socioeconomic status (SES) in childhood are thought to predict psychological distress in later life, partly mediated by education and adulthood SES.

In life-course modelling, SES indicators (eg, occupation or income) are typically specified as reflective latent constructs. However, SES may better be specified as a linear function of its indicators; that is, as a formative latent variable.

We compare the reflective and formative measurement specifications of childhood and adulthood SES and their relationship with psychological distress at midlife.

Key messages

Childhood intelligence and SES and education had indirect effects on psychological distress, which were largely mediated by adult SES.

Formative SES specifications were of limited usability in the context of modelling life-course pathways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Psychological distress was assessed by means of self-reports rather than by clinicians.

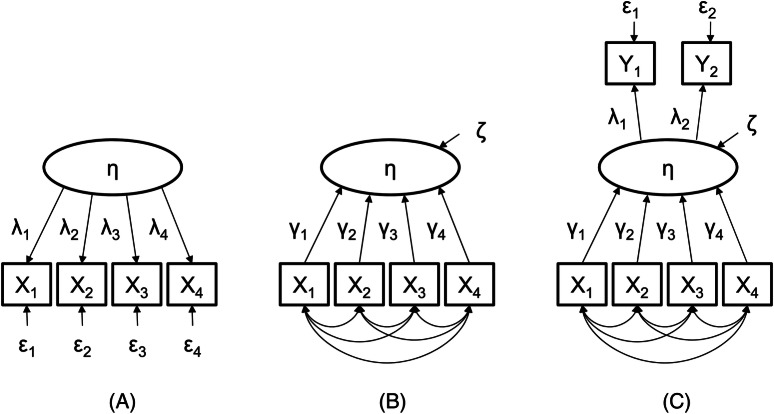

Lower childhood intelligence and socioeconomic status (SES) are associated with deprived living conditions and an increased risk for suffering injuries and illness across the lifespan.1 In line with this, low childhood intelligence and SES have been found to raise the likelihood of experiencing psychological distress in later life,2 3 which precedes psychiatric disorders,4 cardiovascular disease5 and premature mortality.6 Acknowledging that risk factors for morbidity accumulate over time,7–9 their effects on health outcomes and their inter-relations are often tested in comprehensive life-course models that include observed and latent variables.10–12 Latent variables, for example, SES, are typically defined as the common variance in their reflective indicators, such as occupation, income and house tenure, but they might be more appropriately specified as a linear function of formative indicator variables11 13 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Reflective (A) and formative (B) measurement specifications of a latent variable and a multiple-indicators-multiple-causes (MIMIC) model (C), each with four observed indicator variables X1 to X4. η denotes the latent variable in all models. ζ denotes error terms at construct level, while ɛ represents error terms at indicator level. λ1–4 denote factor loadings and γ1–4 denote regression coefficients.

For a reflective latent variable, observed indicators are expected to be at least moderately correlated, as they are thought to be caused by the same underlying factor that captures all their common variance.13 Any variances not common to all reflective indicators are excluded as error. For example, general intelligence is a reflective latent variable,14 15 with the g-factor determining people's scores in each of a set of ability tests. That is, the g-factor relies on the statistical assumption that a latent construct of intelligence caused people's performance across different intelligence tests. By contrast, formative latent variables are statistically defined as consequences of their observed indicators rather than as their cause. Formative indicators are neither assumed nor required to be correlated: they are not caused by a common factor, but they collectively inform a latent construct.13 Variances specific to one indicator and covariances shared by some, but not all, indicators are part of the latent construct; only random variances are treated as error at construct level. Thus, dropping a formative indicator alters a latent construct, because formative indicators capture the entirety of a construct's conceptual domain only as a group. SES comprises ‘observable variations in income, education and occupational prestige and so on; yet it has no measurable reality apart from these variables which are conceived to be its determinants’ (ref. 16, p. 153); thus, SES may be statistically more accurately defined as a consequence rather than a cause of its indicator variables. In other words, the observed indicators of SES do not vary collectively as a function of an underlying common cause, instead they change independently of one another, and thus define SES as a formative latent construct.16 17 That said, latent constructs, like intelligence and SES, are neither inherently formative nor reflective, but their theoretical nature drives their statistical measurement specification.17 Likewise, causality that is implied by statistical models may have little association with actual causal relationships between the observed variables; it merely corresponds with a theory.18

Formative measurement specifications have been mostly explored in simple structural models with few variables and simulated data17 19–21; the results are therefore of limited informative value for life-course models.22 Only one previous study compared formative and reflective SES measurement specifications within a life-course model, concluding that alternative (ie, reflective and formative) specifications of childhood SES did not make a difference for estimating associations between early-life factors and self-reported health status at midlife.11 However, this study11 did not consider the role of adulthood SES, and thus omitted an important determinant of health outcomes in adulthood.7–9 To address this gap, the current study tests life-course models to (1) confirm the association between childhood intelligence, education and SES with psychological distress and (2) compare formative and reflective measurement specifications of childhood and adulthood SES in data from a prospective cohort sample.

Methods

Sample

The Aberdeen Children of the 1950s study (ACONF) comprised 12 150 children (6282 males and 5868 females) born in Aberdeen, Scotland, between 1950 and 1956, and who attended primary school in 1962 when they were aged 6–12 years.23 24 Early-life data were obtained from school records, birth certificates and hospital records. The sample was followed up with a postal questionnaire, between 2001 and 2003, when participants were aged 46–51 years. Of the 12 150 participants, 99% could be traced; of which 4.5% (N=584) had deceased. An overall response rate of 64% (N=7183) was achieved. The rate of attrition was greater for people from lower SES backgrounds,23 which is common in longitudinal cohort studies.

Measures

Intelligence

Within 6 months of their 11th birthday, the children completed four mental ability tests including the Moray House Verbal Reasoning test I and II and an arithmetic and an English test.25 Reliabilities above 0.90 have been reported for all tests.26

Education

Participants’ highest educational qualification was assessed during the follow-up ranging between no formal education, simple school leaving certificate, clerical qualifications, O-levels (certificate of secondary education), Highers or Certificate of Secondary Education, National Certificate and degree level (7-point scale).

SES in childhood

Five variables indicated the participants’ SES at birth: mother's and father's occupation at the time of the child's birth, house tenure, number of rooms and family car ownership.i The father's occupation was coded on a six-point scale ranging between unskilled, semiskilled manual, skilled manual, skilled non-manual, managerial and professional.27 Fathers who were unemployed or had died before the child's birth, were treated as missing, which was previously shown to not impact on the representativeness of the sample.23 The mother's pre-pregnancy occupation was recorded on a six-point scale ranging between unskilled manual, semiskilled manual, skilled manual, distributive, clerical and professional and technical; mothers whose occupational skill level was unknown were treated as missing. Housing tenure (N=1096) and the number of rooms (N=1104) were assessed in subsamples of mothers in 1964. House tenure was coded on a four-point scale ranging between living with relatives, rented from town council, rented from private landlord and house owned. The number of rooms in the house referred to bedrooms and living rooms. Car ownership of family was assessed during the follow-up survey between 2001 and 2003 (dichotomously coded); that is, the participants retrospectively reported if their family had possessed a car when they were children.

SES in adulthood

Four variables indicated SES at midlife: participants’ occupation, income per annum, house tenure and car ownership. Occupation was coded on a six-point scale like like fathers’ occupation.28 Personal gross income per annum, including earnings, benefits, interest from savings and investments, pensions and rent from property, was coded on a nine-point scale ranging from 0=no income to 8=£40 000 per annum or more. Housing tenure was dichotomous, classified as home owner (1) or renting (0). Car ownership was coded on a three-point scale ranging between none, one, two and more.

Psychological distress

Based on four items (General Health Questionnaire; GHQ-4;29), participants rated their enjoyment in day-to-day activities, levels of depression, loss of confidence and overall happiness and well-being over the past few weeks. Each item was rated on a four-point scale ranging from ‘much less than usual’ to ‘much more than usual’. In a large validation study (N=2112), the GHQ-4 was found to correlate 0.80 and above with full-scale GHQ scores.29 In the current study, Cronbach's α was 0.79 in men and 0.80 in women for the four items.

Statistical analysis

Structural equation models were fitted using Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation to allow maximising the available data with missing values30 under the assumption of data missing at random.23 Analyses were conducted separately for men (N=6282) and women (N=5868) because sexes are known to differ with regard to social, psychological and biological variables.11 22

Childhood SES was modelled to impact psychological distress directly, and also to have indirect effects through the mediators of childhood intelligence, education and adult SES. Psychological distress and intelligence were operationalised as reflective latent variables in all models, in line with their theoretical roots.14 29 To scale these two reflective latent variables, one indicator's path parameter for each construct was fixed at 1. Conversely, to scale reflective and formative SES measurement specifications, the path parameter of the father's occupation was restricted to one for childhood SES and own occupation for adult SES.

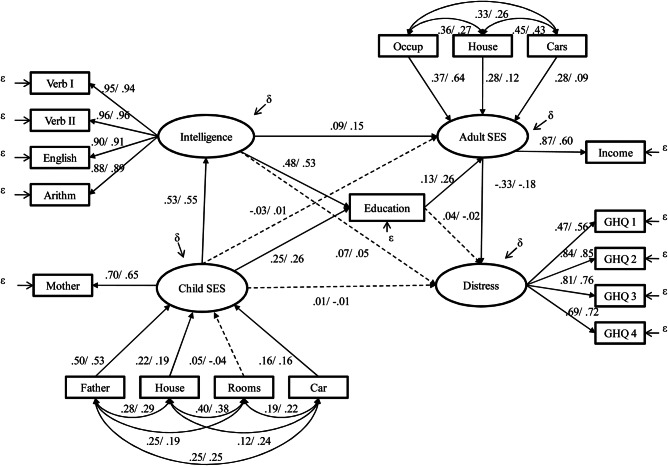

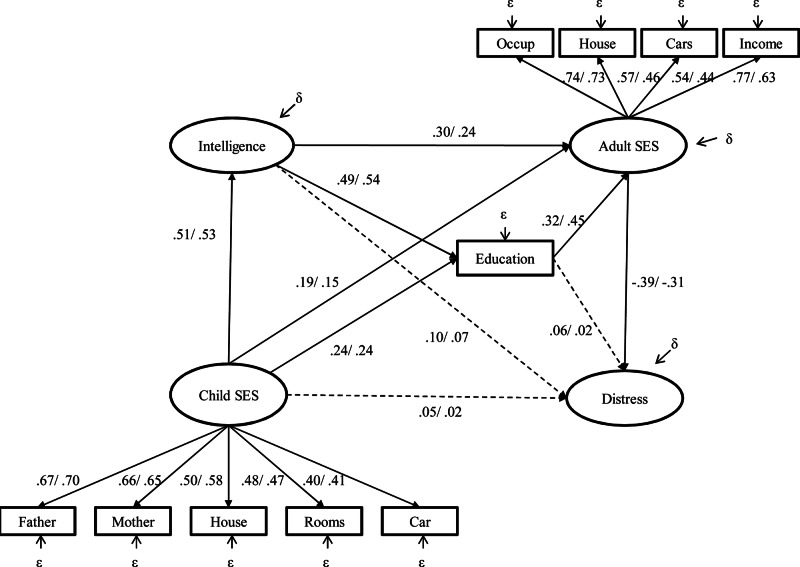

Owing to the indeterminacy of its disturbance term, a formative construct is only identified if it emits at least two direct paths to either: (1) two independent reflective indicators in addition to its formative indicators (see figure 1c); (2) two reflective latent constructs, which are uncorrelated and also have uncorrelated error terms; or (3) one reflective indicator and one reflective construct, which are uncorrelated.13 20 Formative models can also be identified by restricting their error variance to zero,11 which makes an unjustified assumption.13 17 19–21 To achieve the identification of the formative SES constructs, we opted for including two reflective, unrelated indicators. For childhood SES, the mother's occupation was chosen as a reflective indicator, independent of all other model variables and with an independent error term. The other formative indictors of childhood SES were specified to correlate freely, in line with formative modelling conventions.11 13 17 19–21 For adult SES as a formative latent measure, income per annum was operationalised as a reflective indicator with an independent error term, while the other adult SES indicators correlated freely (figure 2). Subsequently, child and adult SES were specified as reflective constructs, respectively, with their five and four indicator variables, each of which had an uncorrelated error term (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Life-course model including formative specifications of childhood and adulthood SES. Note: path coefficients are shown for men/women; non-significant paths (p>0.01) are represented by dashed lines. There were no discrepancies between sexes with regard to the paths’ significance. ɛ denotes error terms for observed variables; δ represents error terms at construct level of latent constructs. Arithm, arithmetic test; Car, no/one car at age 12; Cars, number of cars possessed; Distress, psychological distress; Father, fathers’ occupational social status; GHQ 1–4, General Health Questionnaire items 1–4; House, house tenure; Mother, mothers’ occupational social status; Occup, own occupational social status; Rooms, number of rooms in family home; Verb, verbal test.

Figure 3.

Life-course model including reflective constructs of childhood and adulthood socioeconomic status. Note: path coefficients are shown for men/women. Reflective indicators, corresponding error terms and factor loadings of intelligence and psychological distress have been omitted to sustain graphical clarity (their measurement model is independent of the structural model; see figure 2). For key, please see figure 2.

The model χ² is insufficient for model rejection because of its sensitivity to sample size,31 but incremental fit indices are less dependent on sample size, with recommended minimum values of 0.90 and 0.9532 for the Comparative Fit Index, the Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index and the Tucker-Lewis Index. Also, the root-mean-square error of approximation, based on the non-centrality parameter, indicates an adequate model fit with a value below 0.05.32 Analyses were conducted using SPSS V.18, AMOS V.18 and Mplus V.5.

Results

In both sexes, intelligence test scores were highly intercorrelated, and so were the indicators of psychological distress. Indicators of SES were also positively, albeit moderately correlated (tables 1 and 2).11 16 Observed measures of intelligence, education and childhood and adulthood SES were positively correlated, while psychological distress was generally negatively, albeit modestly linked to other study variables.

Table 1.

Descriptives and correlations in men

| M | SD | N | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verbal I | 103.74 | 13.87 | 5894 | – | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Verbal II | 103.59 | 14.30 | 5875 | 0.91 | – | |||||||||||||||

| 3 | Arithmetic | 104.25 | 14.74 | 5037 | 0.84 | 0.84 | – | ||||||||||||||

| 4 | English | 102.92 | 14.58 | 5037 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.78 | – | |||||||||||||

| 5 | Father's occ | 2.85 | 1.22 | 5952 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.28 | 0.30 | – | ||||||||||||

| 6 | Mother's occ | 3.11 | 1.47 | 5582 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.35 | 0.43 | – | |||||||||||

| 7 | House tenure | 2.30 | 0.77 | 1096 | 0.26 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.31 | 0.25 | – | ||||||||||

| 8 | Rooms | 3.68 | 1.09 | 1104 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 0.39 | – | |||||||||

| 9 | Family car | 1.48 | 0.50 | 3403 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.24 | 0.14 | 0.21 | – | ||||||||

| 10 | Education | 4.55 | 2.12 | 3336 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.17 | – | |||||||

| 11 | Own occ | 4.02 | 1.29 | 3355 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 0.24 | 0.21 | 0.18 | 0.53 | – | ||||||

| 12 | Income per annum | 6.26 | 1.56 | 2794 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.18 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.37 | 0.51 | – | |||||

| 13 | Own house tenure | 1.83 | 0.37 | 3392 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.35 | 0.39 | – | ||||

| 14 | Number of cars | 1.39 | 0.68 | 3429 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.33 | 0.41 | 0.45 | – | |||

| 15 | GHQ-1 | 2.05 | 0.46 | 3427 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.11 | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.09 | −0.10 | −0.18 | −0.12 | − | ||

| 16 | GHQ-2 | 1.71 | 0.73 | 3422 | −0.05 | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.05 | −0.02 | −0.06 | 0.02 | −0.00 | −0.05 | −0.07 | −0.10 | −0.14 | −0.15 | −0.13 | 0.36 | – | |

| 17 | GHQ-3 | 1.53 | 0.69 | 3419 | −0.04 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.00 | −0.03 | 0.07 | 0.08 | −0.03 | −0.06 | −0.08 | −0.19 | −0.17 | −0.17 | 0.33 | 0.70 | – |

| 18 | GHQ-4 | 2.05 | 0.47 | 3420 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.00 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.06 | −0.08 | −0.12 | −0.13 | −0.10 | 0.47 | 0.56 | 0.54 |

Note: Sample sizes are after pair-wise omission.

GHQ 1–4, general health questionnaire items 1–4; M, mean; N, sample size; occ, occupational social status.

Table 2.

Descriptives and correlations in women

| Mean | SD | N | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verbal I | 104.40 | 13.02 | 5409 | – | ||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Verbal II | 104.89 | 13.80 | 5395 | 0.90 | – | |||||||||||||||

| 3 | Arithmetic | 105.09 | 14.10 | 4588 | 0.84 | 0.84 | – | ||||||||||||||

| 4 | English | 104.20 | 14.24 | 4588 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.80 | – | |||||||||||||

| 5 | Father's occ | 2.86 | 1.19 | 5517 | 0.32 | 0.32 | 0.30 | 0.32 | – | ||||||||||||

| 6 | Mother's occ | 3.14 | 1.45 | 5236 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 0.43 | – | |||||||||||

| 7 | House tenure | 2.36 | 0.81 | 1105 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.43 | 0.28 | – | ||||||||||

| 8 | Rooms | 3.73 | 1.06 | 1105 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.10 | 0.39 | 0.16 | 0.38 | – | |||||||||

| 9 | Family car | 1.49 | 0.50 | 3714 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.22 | – | ||||||||

| 10 | Education | 4.17 | 2.11 | 3628 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.59 | 0.62 | 0.36 | 0.37 | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.21 | – | |||||||

| 11 | Own occ | 3.90 | 1.22 | 3667 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.20 | 0.10 | 0.17 | 0.52 | – | ||||||

| 12 | Income p.a. | 4.31 | 1.89 | 2615 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.26 | 0.30 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.37 | 0.45 | – | |||||

| 13 | Own house tenure | 1.83 | 0.38 | 3691 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.26 | 0.11 | – | ||||

| 14 | Number of cars | 1.39 | 0.68 | 3740 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.17 | 0.26 | 0.26 | 0.12 | 0.42 | – | |||

| 15 | GHQ-1 | 2.10 | 0.51 | 3735 | −0.09 | −0.11 | −0.10 | −0.10 | −0.06 | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.06 | −0.11 | −0.10 | −0.04 | −0.15 | −0.15 | – | ||

| 16 | GHQ-2 | 1.79 | 0.79 | 3721 | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.00 | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.10 | −0.10 | −0.06 | −0.16 | −0.18 | 0.44 | – | |

| 17 | GHQ-3 | 1.66 | 0.73 | 3718 | −0.07 | −0.07 | −0.08 | −0.07 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −0.11 | −0.09 | −0.09 | −0.13 | −0.15 | 0.39 | 0.67 | – |

| 18 | GHQ-4 | 2.08 | 0.51 | 3714 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.04 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.05 | −0.04 | −0.08 | −0.05 | −0.05 | −0.10 | −0.12 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.51 |

Note: Sample sizes are after pairwise omission.

GHQ 1–4, general health questionnaire items 1–4; M, mean; N, sample size; occ, occupational social status.

Formative SES specification

Figure 2 shows the overall model with formative constructs for childhood and adult SES. The fit indices suggested a moderate-to-inadequate model fit (table 3).

Table 3.

Model fit indices for models with reflective and formative measurement specifications in men and women

| Model | χ² | df | NFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA (CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | |||||||

| Formative model | 2183.07* | 117 | 0.944 | 0.922 | 0.947 | 0.053 | (0.051 to 0.055) |

| Reflective model | 1219.46* | 126 | 0.969 | 0.962 | 0.972 | 0.037 | (0.035 to 0.039) |

| Women | |||||||

| Formative model | 2073.01* | 117 | 0.943 | 0.920 | 0.946 | 0.053 | (0.051 to 0.055) |

| Reflective model | 1069.99* | 126 | 0.970 | 0.964 | 0.974 | 0.036 | (0.034 to 0.038) |

Note: RMSEA is shown with a 90% CI in parentheses.

*p<0.001.

CFI, Comparative Fit Index; NFI, Normed Fit Index; RMSEA, root-mean-square error of approximation; TLI, Tucker-Lewis Index.

In men and women, reflective indicators intelligence and psychological distress had moderate-to-high factor loadings (p<0.001,ii in all cases). By comparison, path weights of formative childhood and adulthood SES indicators were lower and at times even non-significant; notably, the number of rooms in the family home was non-significant in both men and women (p>0.001). Childhood SES was predictive of intelligence with coefficients 0.53 and 0.55 (p<0.001) in men and women, respectively; in turn, intelligence was strongly associated with educational qualifications with parameters of 0.48 and 0.53 (p<0.001), respectively. These estimates suggest that for every half SD increase in intelligence (ie, about 7.5 IQ points), educational attainment increased by one level. Childhood intelligence and education were associated with adult SES with direct path parameters of 0.09/0.15 and 0.13/0.26 (men/women; p<0.001, in all cases), but childhood SES had no significant association with adult SES (p>0.001) in both sexes. Overall, childhood SES and intelligence and education had close to zero associations with psychological distress at midlife in men and women (p>0.001, in all cases), while adult SES had a direct, negative effect on psychological distress, varying considerably across men and women with coefficients −0.33 and −0.18, respectively. Sex differences were only observed in the path weights of adult SES (eg, occupational social status with 0.37 and 0.64 in men and women, respectively; figure 2). The overall model explained 10.4% of the total variance in psychological distress in men and 3% in women.

Reflective SES specification

Model-fit indices suggested a good fit to data of the ‘reflective’ model in men and women (table 3) and confirmed an improvement in fit compared with the ‘formative’ model.iii The factor loadings of the reflective indicators ranged from 0.40 to 0.70 for childhood SES and from 0.44 to 0.77 for adult SES (p<0.001, in all cases), whereas formative paths had ranged from −0.04 to 0.53 for birth SES and 0.09 to 0.64 for adult SES in men and women, respectively (figures 2 and 3). Also, reflective factor loadings were more invariant across sexes than formative path weights. Childhood SES significantly predicted childhood intelligence with coefficients 0.51 and 0.53, education with coefficients of 0.24 and adult SES with values 0.19 and 0.15 (p<0.001, in all cases for men and women, respectively). Like before, childhood intelligence was significantly, positively associated with education at 0.48/0.53 and also with adult SES at 0.30/0.24 (p<0.001, in all cases for men and women, respectively). Adult SES was the strongest predictor of psychological distress at midlife with paths of −0.39 and −0.31 (p<0.001) for men and women, respectively. In women, intelligence had a negligible direct effect on psychological distress; however, in men, its parameter of 0.10 was significant (p<0.001). In line with the formative model, childhood intelligence and SES and education do not directly affect psychological distress in later life, but their association was mediated by adult SES. Overall, the reflective model accounted for 9% of the total variance in well-being in men, and 6% in women.

Discussion

SES has far-reaching implications for an array of life outcomes, illustrated by its associations with better cognition and health outcomes.1 7–9 Here we investigated the effects of childhood intelligence and SES on psychological distress at midlife, as mediated by education and adult SES, and we compared the reflective and formative measurement specifications of SES in the context of life-course modelling.

Principal findings

Higher adult SES (eg, more advanced occupational position or higher income) was associated with lower levels of psychological distress at midlife. Childhood SES, intelligence and education had negligible direct effects on psychological distress at midlife; however, most of their influences were indirect and mediated through adult SES. Our results are generally in concordance with other studies that demonstrated the importance of adult SES for mental health outcomes.33 However, they contradict the previous reports of a direct, protective effect of childhood intelligence on psychological distress, which remained significant after adjusting for childhood and adulthood SES.2–3 The discrepancy in findings may be due to several reasons. For one, Gale et al2 and Hatch et al3 tested binary logistic regression models in the British Cohort Studies 1946, 1958 and 1970 with list-wise omission of cases with missing data, which significantly reduced sample sizes by more than half (eg, the British Cohort Study 1970 included initially about 17 200 people, but only 6074 were included in the analysis sample2). By comparison, our statistical approach used structural equation models with FIML, which allows including all observed data points, and thus keeping the full sample size (ie, 12 150).30 As a consequence, the current analysis sample is more representative of the original study population than it was the case in previous reports.2–3 For the other, our study used the GHQ-4, which has fewer items and may be psychometrically less robust than the measures used by Gale et al2 and Hatch et al3 (eg, the GHQ-2829). It is possible that the presently evaluated distress measure was not sensitive enough to detect a direct effect of intelligence.

In line with the previous reports, 19 34 models with formative SES specification underestimated both measurement and structural paths compared with the reflective approach. Also, differences in modelling strategy were clearly reflected by model fit indices, with the model that included formative SES specifications proving a poorer data fit.13 20 Furthermore, when both SES were formatively specified, childhood SES had no significant effect on adult SES, which contradicts the previous research.10 35 This is particularly notable because cohort studies from Britain typically find a robust relationship between childhood and adulthood SES, although the strength of association tends to vary across samples and studies.9–11 22 By contrast, under the reflective modelling approach, childhood and adulthood SES were significantly associated.iv

Formative measurement specification

Formatively specified constructs need to emit direct paths to two independent reflective indicator variables, which may be latent or directly observed, to be identified. This is often problematic in life-course modelling for one because the models’ observed and latent variables are typically inter-related11–13 22 and for the other because the number of observed indicators is usually too limited to allow specifying some as formative and others as reflective. Thus, it may be impossible to specify formative variables in a life-course model without reducing the overall structural model to a meaningless accumulation of linear functions.20 Most importantly, however, formatively specified latent variables cannot be compared across models because their empirical realisation depends on both the indicators and the other variables within a model.13 20 In the current study, we arbitrarily chose one observed indicator to be the reflective identifier of the formative latent SES construct (eg, mother's occupation for childhood SES). If we specified any other indicator as a reflective identifier, the associated latent construct, its disturbance term and its emitted structural paths were changed.v The choice of the reflective indentificator is all, but arbitrary; however, it is unclear how to select one.36 As a consequence, formatively specified latent variables are unsuitable in the context of life-course models because they do not allow cross-model and cross-sample comparisons.

Strengths and limitations

This study's strengths are a large cohort sample, a long follow-up period and the assessment of numerous variables, which allowed fitting life-course models with four latent constructs. It also has weaknesses. First and because of attrition, people from less privileged social backgrounds are somewhat under-represented,23 which might result in an underestimation of the true effect sizes despite the application of FIML.30 Second, psychological distress was self-reported using a short version of the GHQ, that is, the GHQ-4, which may be psychometrically weaker than other assessment instruments of psychological distress, such as, for example, the Malaise Inventory.2 While self-reported health measures may be valid and reliable in some contexts,29 37 38 it is unclear if the GHQ-4 is an adequately sensitive measure; that said, the GHQ-4 correlates 0.80 with its longer version (ie, GHQ-28) and has high internal consistency reliability.29 Third, some variables were treated as continuous, although they are ordered or categorical (eg, having a family car in childhood SES). As a consequence, measurement paths could be biased, albeit equally in reflective and formative measurement models. Finally, the fitted life-course models accounted for small amounts of variance in psychological distress, suggesting that future research must explore other risk factors, for example, social support networks.39

Conclusions

Childhood intelligence and SES and education influence psychological distress at midlife indirectly through their association with adult SES. Formative measurement specifications of SES were problematic in the context of life-course modelling, while reflective measurement specifications of SES constituted a more reliable approach. Thus, we encourage social scientists, when applying covariance structure analyses to test life-course models, to avoid formative measurement specifications because—as we have shown here—they are of limited usability.

Supplementary Material

Contributors: SvS, IJD and GH-J each made substantial contributions to the conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data; helped drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; and approved the final version to be published.

Funding: ‘The Children of the 1950s’ project is funded by the Medical Research Council and the Chief Scientist Office. The current report, however, was not directly supported by funding.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the revitalisation of ACONF was by the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Ethics Committee, the Grampian Research Ethics Committee, and the Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee for Scotland.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data are available upon request and a decision from the ACONF study team steering group (http://www.abdn.ac.uk/childrenofthe1950s/).

ACONF also contains information on mother's and father's education. These variables are highly skewed and have no meaningful variance. Therefore, they were not included.

Owing to the large sample sizes in the current study, we chose a stricter probability level (p <0.001) than typically recommended (p <0.05).

For simplicity, we will refer to the ‘formative model’ as the structural equation model with formative SES, and to the ‘reflective model’ as the structural equation model including reflective SES.

To rule out that education accounted for all the direct effects of childhood SES on adult SES, we rerun all models excluding education as a mediating variable; the results were unchanged.

We conducted the corresponding analyses for all possible combinations of reflective and formative indicators for each SES construct (results not included here).

[END]

References

- 1.Batty GD, Deary IJ, Gottfredson L. Premorbid (early life) IQ and later mortality risk: systematic review. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:278–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gale CR, Hatch SL, Batty GD, et al. Intelligence in childhood and risk of psychological distress in adulthood: the 1958 National Child Development Survey and the 1970 British Cohort Study. Intelligence 2009;375:92–9 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hatch SL, Jones PB, Kuh D, et al. Childhood cognition and adult mental health in the British 1946 Birth Cohort. Soc Sci Med 2007;64:2285–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gulliver A, Griffith KM, Christensen H, et al. A systematic review of help-seeking interventions for depression, anxiety and general psychological distress. BMC Psych 2012:12:81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamer M, Molloy GJ, Stamatakis E. Psychological distress as a risk factor for cardiovascular events: pathophysiological and behavioral mechanisms. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:2156–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huppert FA, Whittington JE. Symptoms of psychological distress predict 7-year mortality. Psychol Med 1995;25:1073–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh-Manoux A, Ferrie JE, Chandola T, et al. Socioeconomic trajectories across the lifecourse and health outcomes in midlife: evidence for the accumulation hypothesis? Int J Epidemiol 2004;33:1072–1079.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ben-Shlomo Y, Davey Smith G. Deprivation in infancy and adult life: which is more important for mortality risk? Lancet 1991;337:530–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stansfeld SA, Clark C, Rodgers B, et al. Repeated exposure to socioeconomic disadvantage and health selection as life course pathways to mid-life depressive and anxiety disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2011;46:549–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feinstein L, Bynner J. The importance of cognitive development in middle childhood for adulthood socio-economic status, mental health, and problem behavior. Child Dev 2004;75:1329–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hagger-Johnson G, Batty GD, Deary IJ, et al. Childhood socioeconomic status and adult health: comparing formative and reflective models in the Aberdeen children of the 1950s (prospective cohort study). J Epidemiol Commun H 2011;8:20–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh-Manoux A, Clarke P, Marmot M. Multiple measures of socioeconomic position and psychosocial health: proximal and distal effects. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:1192–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bollen KA, Lennox R. Conventional wisdom on measurement: a structural equation perspective. Psych Bull 1991;110:305–14 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson W, Bouchard TJ, Jr, Krueger RF, et al. Just one g: consistent results from three test batteries. Intelligence 2004;184:95–107 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spearman CE. General intelligence: objectively determined and measured. Am J Psychol 1904;15:201–93 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heise DR. Employing nominal variables, induced variables, and block variables in path analysis. Soc Met Res 1972;1:147–73 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarvis CB, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff PM. A critical review of construct indicators and measurement model misspecification in marketing and consumer research. J Cons Res 2003;30:199–218 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borsboom D, Mellenbergh GJ, Van Heerden J. The theoretical status of latent variables. Psych Rev 2003;110:203–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Law KS, Wong CS. Multidimensional constructs in structural equation analysis: an illustration using the job perception and job satisfaction constructs. J Manag 1999;25:143–60 [Google Scholar]

- 20.MacCallum RC, Browne MW. The use of causal indicators in covariance structure models: some practical issues. Psych Bull 1993;114:533–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff PM, Jarvis CB. The problem of measurement model misspecification in behavioral and organizational research and some recommended solutions. J App Psych 2005;9:710–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:285–93 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Batty GD, Morton SM, Campbell D, et al. The Aberdeen children of the 1950s cohort study: background, methods and follow-up information on a new resource for the study of life course and intergenerational influences on health. Paediatr Perinat Ep 2004;18:221–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leon D, Lawlor D, Clark H, et al. Cohort profile: the Aberdeen children of the 1950s study. Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:549–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomson G. An analysis of performance test scores of a representative group of Scottish children. London, UK: University of London Press, 1940 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deary IJ, Whalley LJ, Starr JM. A lifetime of intelligence: follow-up studies of the Scottish mental surveys of 1932 and 1947. New York: American Psychological Association, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Office of Population Censuses and Surveys Classification of occupation 1951. London: HMSO, 1951 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Office of Population Censuses and Surveys Classification of occupation 1990. London: HMSO, 1990 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobsen B, Hasvold T, Hoyer G, et al. The general health questionnaire: how many items are really necessary in population surveys? Psych Med 1995;25:957–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arbuckle JL. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides GA, Schumacker RE, eds. Advanced structural equation modeling: issues and techniques. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1996:243–77 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jöreskog KG. A general approach to confirmatory maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika 1969;34:183–202 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equation Model 1999;6:1–55 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stansfeld SA, Clark C, Rodgers B, et al. Childhood and adulthood socio-economic position and midlife depressive and anxiety disorders. Br J Psychiatry 2008;192:152–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Diamantopoulos A, Riefler P, Roth KP. Advancing formative measurement models. J Bus Res 2008;61:1203–18 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strenze T. Intelligence and socio-economic success: a meta-analytic review of longitudinal research. Intelligence 2007;35:401–26 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Diamantopoulos A. Formative indicators: introduction to the special issue. J Bus Res 2008;61:1201–2 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Singh-Manoux A. The association between self-rated health and mortality in different socioeconomic groups in the GAZEL cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2007;6:1161–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beckett M, Weinstein M, Goldman N, et al. Do health interview surveys yield reliable data on chronic illness among older respondents? Am J Epidemiol 2000;151:315–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stansfeld S, Fuhrer R, Shipley M. Types of social support as predictors of psychiatric morbidity in a cohort of British civil servants (Whitehall II study). Psych Med 1998;28:881–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.