Abstract

Background

Despite increasing availability of HIV-1 testing, education, and methods to prevent transmission, Indian women and their children remain at risk of acquiring HIV. We assessed the sero-prevalence and awareness about HIV among pregnant women presenting to a private tertiary care hospital in South India.

Methods

Sero-prevalence was determined via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing, and questionnaires were analyzed using chi-square statistics and odds ratios to look for factors associated with HIV positivity.

Results

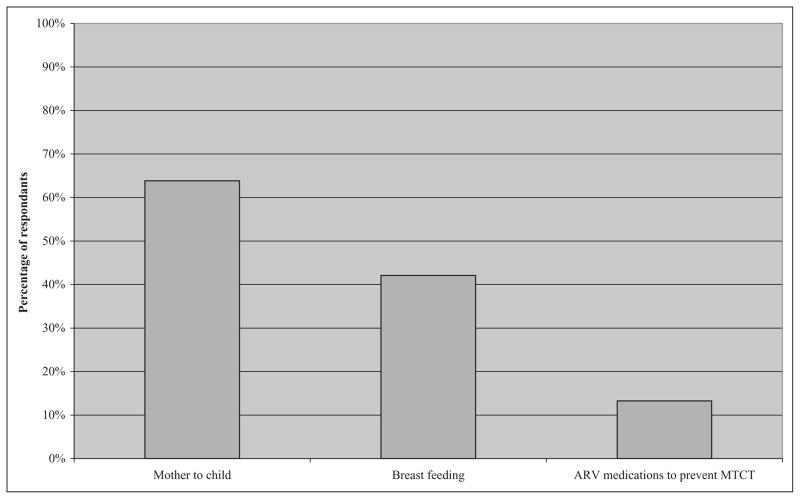

A total of 7956 women who presented for antenatal care were interviewed. Fifty-one women of the 7235 women who underwent HIV testing (0.7%) were found to be HIV positive. Awareness of mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV (64%), HIV transmission through breast milk (42%), and prevention of MTCT (13%) was low.

Conclusions

There is a need to educate South Indian women about HIV to give them information and the means to protect themselves and their unborn children from acquiring HIV.

Keywords: HIV, sero-prevalence, awareness, pregnancy, antenatal, India

Introduction

The world’s second most populous country, India, is experiencing a highly varied HIV epidemic that appears to be stable or diminishing in some parts while growing at a modest rate in others. According to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Epidemic Update 2007, the last year for which country-specific data are available, between 2 and 3.1 million Indians were living with HIV/AIDS in 2006. Although the national adult HIV prevalence, based partly on the antenatal clinic surveillance data, is estimated to be 0.36%, there are many areas in the country that have a significantly higher prevalence. Recalculations of national sero-prevalence estimates in 2006,1 which had a significant impact on worldwide estimates,2 highlight the importance of basic but reliable sero-prevalence studies and the importance of collecting data from as many different sources as possible. Additionally, the lack of accuracy in sero-prevalence estimates and variety of data collection methods make it difficult to confirm the decline in sero-prevalence, which appears to be taking place in some parts of India3 and has resulted in some controversy.4

Tamil Nadu, the sixth largest state in India (per the 2001 census), holds the distinction of being the first state to report a documented case of HIV infection in India and of being one of the first to report declines in incidence rates in the years following the start of HIV intervention programs.3 However, even within the state, the sero-prevalence and impact of programs may vary. The prevalence of HIV infection among mothers who attended Prevention of Parent to Child Transmission (PPTCT) programs in 30 district hospitals in Tamil Nadu state was 0.69% and 0.41% in 2002 and 2005, respectively.5 The first study done in the antenatal clinics at Christian Medical College (CMC), a private tertiary referral hospital in Vellore, Tamil Nadu, in 1993 showed a sero-prevalence of 0.054%.6 A recent study on community prevalence of HIV in the same locality and during a similar time period as the data presented in this study revealed a sero-prevalence of 0.66% among 1512 rural participants and 1.4% among the 1358 urban participants, with a prevalence almost equal between men and women.7 No studies have yet been done to evaluate the sero-prevalence among women presenting to the antenatal clinics at this site since the introduction of the state-sponsored PPTCT program.

Mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) of HIV leads to the birth of approximately 56 700 HIV-positive Indian children each year.8 The Indian government recognizes the seriousness of this problem, and information about MTCT is part of the government’s overall strategy to combat HIV, known as the National AIDS Control Program Phase III (NACP-III). The National Behavioral Surveillance Survey (BSS) conducted by India’s National AIDS Control Organization (NACO) in 2001 among the general population found that knowledge of vertical transmission and transmission through breast-feeding was 81% and 72.5%, respectively, in Tamil Nadu.9 This had increased only slightly by 2005 when the second BSS was undertaken, to 82% and 78% for vertical transmission and breast-feeding, respectively.10 A separate study conducted in Chennai, the closest major urban center to Vellore, showed that 78% of antenatal clinic attendees were aware of MTCT, but only 36% were aware of methods to prevent it.11 The same study also found that 86% of women reported willingness to undergo HIV testing, but 46% would not do so without their husbands’ permission. The lack of independence in decision making combined with lack of awareness and lack of resources combine to form a significant barrier to HIV testing.

The objectives of this study were to determine the acceptability of HIV testing and assess HIV sero-prevalence and awareness among women presenting for antenatal at a large private referral hospital and 2 associated rural level hospitals in Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India.

Methods

Study Area and Participants

Christian Medical College is a private tertiary-level 1638-bed academic hospital located in Vellore, Tamil Nadu. The department of Community Health and Development (CHAD) is an 80-bed rural health unit staffed by CMC faculty that serves 106 000 persons and has offered HIV education programs in the surrounding villages in the years prior to this study. The Rural Unit for Health and Social Affairs (RUHSA) is a 60-bed rural health unit that serves 120 000 persons; it has not had any HIV education programs outside of this study. In 2004–2005, these 3 campuses saw 1 255 791 outpatient visits and 82 883 inpatients from all over India but particularly from Tamil Nadu and West Bengal. Community Health and Development and RUHSA saw patients only from the local population. A total of 12 958 births were recorded, which is approximately 36 births each day. All women presenting for an initial visit to any of the antenatal clinics at these sites from September 2003 to September 2004 (until November 2004 for RUHSA) were included in the study. Women who were returning for a follow-up visit for the same pregnancy were not reinterviewed. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards (IRB) at CMC and The Miriam Hospital, Brown University.

Data Collection

Study participants were interviewed individually by a social worker or sociologist, during which time the study was explained, consent for participation obtained, and responses to the questionnaire marked down by the interviewer. All nurses, social workers, and interviewers conducted interviews in the participant’s native language, usually Tamil. Questionnaire information was recorded in individual booklets and kept confidential by individual study numbers, separate from the patient’s hospital identification number. Questionnaire topics included demographics, obstetric history, knowledge about HIV/AIDS, acceptability of HIV testing, and an assessment of HIV risk factors, including number of sexual partners and blood transfusions. Questions about HIV/AIDS awareness focused on sources of information, correct and incorrect methods of transmission, methods of preventing transmission, and treatments or cures for HIV/AIDS.

HIV Testing

After the completion of the questionnaire, participants were given education about HIV, including the possibility for transmission of HIV from mother to child, and detailed options for prevention. They were then encouraged to undergo testing. HIV testing was done by the virology department using Genedia HIV-1 and -2 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (3rd generation kits, Greencross Life Sciences, S. Korea). Positive samples were retested with Bio-Rad Gen-screen HIV-1 and -2 ELISA kits (California). Women who tested positive received posttest counseling by an obstetrician trained in HIV care and were scheduled for regular follow-up with her throughout their pregnancy and afterward. All HIV-positive women were offered prophylactic antiretroviral therapy (ART) for the prevention of maternal–child transmission, caesarian section, and posttest counseling including psychosocial support. This protocol follows guidelines developed for use in India by one of the authors of this study12 based on studies showing the efficacy of zidovudine (ZDV) for mother and child, as well as risk reduction with caesarian sections.13–15 These guidelines include options for starting ZDV as early as 14 weeks of gestation (depending on patient’s financial resources) but at 36 weeks at latest, intrapartum oral or intravenous (IV) ZDV for the mother and oral ZDV to the infant for 6 weeks. In some cases, women received single-dose nevirapine (NVP) in addition to the ZDV regimen, generally if they had presented late and not received ZDV during pregnancy.

Data Analysis

Questionnaire data along with HIV sero-positivity were analyzed for significant correlations using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 17.0 (Chicago, Illinois). Statistical significance was assessed using a chi-square test. Odds ratios were performed using SPSS to determine particular factors associated with HIV positivity and HIV testing (at CMC only) among the participants.

Results

Sero-prevalence, Sociodemographics, and Odds Ratios of HIV Risk

In total 7956 women were interviewed, of whom 7235 (91%) underwent HIV testing; 51 were found to be HIV positive (0.71%). Of the women who underwent HIV testing, 5308 (73.3%) and 1927 (26.6%) were from urban and rural sites, respectively. The sociodemographic distribution of the study group is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic Distribution of Study Participants by Sitea

| Urban

|

Rural

|

Total

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMC | (%) | CHAD | (%) | RUHSA | (%) | Total | (%) | |

| Age (P < .001) | ||||||||

| <19 | 339 | (6%) | 72 | (16%) | 206 | (14%) | 617 | (8%) |

| 20–24 | 2497 | (42%) | 275 | (59%) | 915 | (61%) | 3687 | (46%) |

| 25–29 | 2198 | (37%) | 94 | (20%) | 319 | (21%) | 2611 | (33%) |

| >30 | 949 | (16%) | 22 | (5%) | 64 | (4%) | 1035 | (13%) |

| Education (P < .001) | ||||||||

| Secondary or above (above ninth) | 4932 | (84%) | 218 | (54%) | 675 | (50%) | 5825 | (76%) |

| Middle school (sixth to eighth) | 720 | (12%) | 139 | (34%) | 509 | (38%) | 1368 | (18%) |

| Primary or less | 215 | (4%) | 46 | (11%) | 171 | (13%) | 432 | (6%) |

| Never attended school | 115 | (2%) | 60 | (13%) | 154 | (10%) | 329 | (4%) |

| Religion (P < .001) | ||||||||

| Hindu | 4892 | (82%) | 445 | (96%) | 1440 | (95%) | 6777 | (85%) |

| Others | 1093 | (18%) | 18 | (4%) | 68 | (5%) | 1179 | (15%) |

| Marital status (P = .36) | ||||||||

| Married | 5971 | (99.8%) | 460 | (99.4%) | 1504 | (99.7%) | 7935 | (99.7%) |

| Others | 14 | (0.2%) | 3 | (0.6%) | 4 | (0.3%) | 21 | (0.3%) |

| Total | 5985 | 463 | 1508 | 7956 | ||||

| Number of women tested | 5308 | (88.7%) | 463 | (100%) | 1464 | (97.1%) | 7235 | (90.9%) |

| Sero-prevalence by site | 37 | (0.70%) | 1 | (0.22%) | 13 | (0.89%) | 51 | (0.70%) |

Abbreviations: CHAD, Community Health and Development; CMC, Christian Medical College; RUHSA, Rural Unit for Health and Social Affairs.

P values are for urban versus rural.

The odds ratios for factors associated with HIV positivity are shown in Table 2. The sero-prevalence was 0.7% among both rural and urban women. All but one of the women who tested HIV positive reported that they had only 1 lifetime sexual partner, and only 18 of the HIV-negative women reported more than 1 sexual partner. Only 1 of the 104 women who reported having had a blood transfusion was HIV positive and 8 (0.7%) of the 1124 women who had had a major surgery were HIV positive.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios for Sociodemographic Factors Associated With HIV Status

| Variables | HIV Status

|

OR | 95% CI | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (N = 51)

|

Negative (N = 7184)

|

|||||||

| n | % | n | % | |||||

| Age | ||||||||

| ≤19 | 4 | 0.7 | 578 | 99.3 | 3.2 | 0.6 | 17.3 | .184 |

| 20–24 | 33 | 1.0 | 3342 | 99.0 | 4.5 | 1.1 | 18.7 | .048 |

| 25–29 | 12 | 0.5 | 2345 | 99.5 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 10.4 | .393 |

| ≥30 | 2 | 0.2 | 918 | 99.8 | 1.0 | |||

| Education | ||||||||

| Never attended | 2 | 0.6 | 296 | 99.3 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 5.0 | .813 |

| Primary or less | 7 | 1.8 | 376 | 98.2 | 3.3 | 1.4 | 7.5 | .003 |

| Middle (sixth-eighth) | 12 | 1.0 | 1231 | 99.0 | 1.7 | 0.9 | 3.4 | .112 |

| Above ninth | 30 | 0.6 | 5278 | 99.4 | 1.0 | |||

| Awareness level | ||||||||

| Lowest tercile | 19 | 0.9 | 2199 | 99.1 | 1.5 | 0.8 | 2.7 | .203 |

| Middle tercile | 8 | 0.9 | 872 | 99.1 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 3.5 | .268 |

| Highest tercile | 24 | 0.6 | 4104 | 99.4 | 1.0 | |||

| House type | ||||||||

| Thatched | 19 | 1.9 | 962 | 98.1 | 5.7 | 2.8 | 11.5 | <.001 |

| Tiled | 19 | 0.8 | 2480 | 99.2 | 2.2 | 1.1 | 4.5 | .025 |

| Terraced | 13 | 0.3 | 3736 | 99.7 | 1.0 | |||

| Fuel type | ||||||||

| Cheaper | 32 | 1.2 | 2632 | 98.8 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 5.1 | <.001 |

| More expensive | 19 | 0.4 | 4549 | 99.6 | 1.0 | |||

| Income bracket | ||||||||

| <R1500 | 34 | 1.0 | 3460 | 99.0 | 2.2 | 0.3 | 16.4 | .415 |

| R1501–R5000 | 14 | 0.5 | 2621 | 99.5 | 1.2 | 0.2 | 9.3 | .849 |

| R5001–R15 000 | 2 | 0.2 | 875 | 99.8 | 0.5 | 0.05 | 5.8 | .589 |

| >R15 000 | 1 | 0.4 | 228 | 99.6 | 1.0 | |||

| Site | ||||||||

| Urban | 37 | 0.7 | 5271 | 99.3 | 1.0 | |||

| Rural | 14 | 0.7 | 1913 | 99.3 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 2.0 | .895 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Knowledge on Transmission and Prevention

Only 19% of women could identify all the correct and incorrect methods of HIV transmission accurately. Almost 39% knew all the correct methods of transmission, but 26% of the women could not identify any correctly. Overall awareness of transmission via sexual contact was 73%, sharing needles was 67%, blood transfusion was 67%, vertical transmission was 64%, and breast-feeding was 42%. Belief in or uncertainty about incorrect methods of transmission was prevalent at all sites, with 64% of all respondents unable to correctly identify all 4 incorrect methods of transmission, including casual contact, sharing utensils, insects/mosquitoes, and sharing toilets. Knowledge about most methods of prevention (clean needles, single partner, avoiding infected blood) exceeded 70% among CMC and CHAD populations, although 41% of respondents were unsure about the use of condoms for prevention. Only 13% of women overall believed that it was possible to prevent transmission to children with antiretroviral (ARV) medications during pregnancy, while 74% were unsure. The participants’ knowledge about MTCT of HIV and prevention is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Awareness of mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) and means to prevent it. ARV indicates antiretroviral.

Awareness of treatment for HIV was also low (32%). In most sites, participants were evenly split between the answers yes, no, and do not know when asked about treatment for HIV. Almost 10% of the 7956 women interviewed believed there is a cure for HIV, and an additional 39% were unsure.

Acceptability of HIV Testing and Pre-Interview Awareness of HIV-Positive Women

Although many women had been unaware of the possibility to prevent MTCT, counseling on this issue led to very high levels of interest in testing. Over 95% of women at each site agreed that HIV testing is important and consented to be tested. At CMC, where women were encouraged to undergo testing but required to pay for it, 88% of the women were tested. At CHAD, where testing was offered free through this study and awareness of HIV was higher, 100% of women were tested. At RUHSA, testing was also offered free of charge, but 44 women (2.9%) chose not to receive the free test. There was no significant difference in age, education, income, socioeconomic markers (type of house and cooking fuel), or awareness about HIV issues between women who chose not to be tested and those who were tested at RUHSA; however, all 44 of the women who were not tested stated that they did not believe that ARV medications could prevent MTCT (P = .178). At CMC, not being tested was associated with lower educational level, lower socioeconomic markers, and lower overall awareness (all P < .001). A significantly higher percentage of women who were tested at CMC reported belief in MTCT of HIV (71.4% to 65.4%, P = .001). Odds ratios for factors associated with HIV testing at CMC are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Odds Ratios for Factors Associated With HIV Testing at CMC

| Variables | HIV Testing

|

OR | 95% CI | P Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Tested (N = 677)

|

Tested (N = 5308)

|

|||||||

| n | % | n | % | |||||

| Age | ||||||||

| ≤19 | 34 | 10.0 | 307 | 90.0 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 1.2 | .266 |

| 20–24 | 284 | 11.4 | 2213 | 88.6 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.2 | .487 |

| 25–29 | 243 | 11.1 | 1955 | 88.9 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.1 | .344 |

| ≥30 | 116 | 12.2 | 833 | 87.8 | 1.0 | |||

| Education | ||||||||

| Never attended | 28 | 24.3 | 87 | 75.7 | 2.9 | 1.9 | 4.5 | <.001 |

| Primary or less | 43 | 20.2 | 170 | 79.8 | 2.3 | 1.6 | 3.3 | <.001 |

| Middle (sixth-eighth) | 114 | 15.8 | 606 | 84.2 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 2.1 | <.001 |

| Above ninth | 489 | 9.9 | 4442 | 90.1 | 1.0 | |||

| Awareness level | ||||||||

| Lowest tercile | 197 | 14.1 | 1198 | 85.9 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.7 | <.001 |

| Middle tercile | 68 | 9.9 | 616 | 90.1 | 0.9 | 0.7 | 1.2 | .624 |

| Highest tercile | 412 | 10.6 | 3488 | 89.4 | 1.0 | |||

| House type | ||||||||

| Thatched | 83 | 17.9 | 381 | 82.1 | 1.9 | 1.5 | 2.5 | <.001 |

| Tiled | 243 | 11.7 | 1829 | 88.3 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.4 | .074 |

| Terraced | 351 | 10.2 | 3094 | 89.8 | 1.0 | |||

| Fuel type | ||||||||

| Cheaper | 208 | 15.5 | 1130 | 84.5 | 1.6 | 1.4 | 2.0 | <.001 |

| More expensive | 469 | 10.1 | 4176 | 89.9 | 1.0 | |||

| Income bracket | ||||||||

| <R1500 | 328 | 13.9 | 2025 | 86.1 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 1.3 | .676 |

| R1501–R5000 | 226 | 9.3 | 2214 | 90.7 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.8 | .004 |

| R5001–R15 000 | 84 | 9.0 | 846 | 91.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.9 | .006 |

| >R15 000 | 39 | 14.9 | 223 | 85.1 | 1.0 | |||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CMC, Christian Medical College; OR, odds ratio.

Of women seeking antenatal care at CMC, almost 40% had previously been tested for HIV, whereas few women at CHAD (6.5%) and RUHSA (1%) had been tested; the overall rate of prior testing was 27.9%. Routine antenatal HIV testing had not been instituted at CHAD and RUHSA until this study. Of the women who did not undergo HIV testing as part of this study, 245 (34%) reported having a negative HIV test previously. Over half of the women found to be HIV positive in this study had previously been tested for HIV, although they were not asked where. Of the HIV-positive women who had been tested previously, 75% had been positive; thus, 41% of the women who tested positive in this study had already known their HIV status. An additional 14% of those who tested positive had been tested previously but were found to be negative at that time (according to patient reported data). Further analysis of the 21 HIV-positive women who had been aware of their status at the time of completing the questionnaire (and presumably had had previous education on HIV when diagnosed) revealed that 11 (52%) were aware of MTCT and 6 (29%) were aware of ARV medications for PMTCT. Of the 30 women who were newly informed of their HIV status after completing the questionnaire, 15 (50%) were aware of MTCT and 3 (10%) were aware of ARV medications for PMTCT.

Discussion

Importance of Accurate “Pure” (Nonmodeled) Sero-Prevalence Studies

Recalculations of India’s HIV sero-prevalence have had a dramatic effect on worldwide estimates. This study was performed at the same time that nationwide estimates projected an HIV sero-prevalence in India of 5 million people; recalculation of the data led this estimation to be reduced to 3 million people.2 Much of the resulting decrease in estimated sero-prevalence was due to incorrectly interpreted antenatal and sexually transmitted infection (STI) clinic testing data, largely obtained from government health centers; the authors of the first study to highlight this problem hypothesized that HIV-positive persons were overly represented in the public hospitals because of referral by private physicians.1 The flaw in prior estimates highlights the need for more sources of raw data, especially outside of the public hospital system, on which to base calculations of overall sero-prevalence. This has now been accomplished by NACO’s expansion of surveillance testing to all districts of the country, including 1122 sentinel surveillance sites.8 This study found a sero-prevalence rate of 0.7% in 2004, which was higher than the ANC-specific sero-prevalence of 0.41% in the entire state of Tamil Nadu reported at that time5; however, as CMC is a nationally known referral hospital with a history of assisting financially limited patients, it is likely that patients were preferentially referred there, similar to the phenomenon proposed by Dandona and colleagues.1

The lack of a significant difference between rural and urban sero-prevalence rates in our study is consistent with earlier data that the HIV epidemic in Tamil Nadu has become generalized;16 however, our data differ from another study done among the general population of the same study area, which found a significantly higher rate in the urban population.7 This disconnect emphasizes the importance of collecting HIV surveillance data from multiple sources and the danger of assuming that data from any specific clinic or source should be representative of the entire population.

Awareness and Education

The participants in this study represent a wide variety of educational levels and backgrounds and highlight the varied substrate for educational programs encountered in India. The high levels of awareness on most aspects of HIV transmission and prevention reveal that the national, state, and CHAD-run educational programs have had a dramatic impact on the awareness of the population and are likely the reason for any decline in sero-prevalence rates in the last few years.

Unfortunately, this study also demonstrates the lack of education about several topics, including maternal transmission of HIV through breast milk, prevention of HIV with ARV medications, and existence of treatment for HIV. The limited awareness of these issues among women who had high levels of awareness about other issues indicates that these topics have not been effectively communicated to the population, and as such, women are losing the opportunity to avail themselves of services that could save both their own lives as well as the lives of their children.

Acceptability of Testing and Study Limitations

Limitations of this study included the lack of universal HIV testing among participants, likely due at least in part to financial constraints, which led to 721 women not being tested. If our sero-prevalence estimate holds true for the entire study group, at least 5 HIV-positive women missed the opportunity to prevent HIV transmission to their children. If in fact the sero-prevalence was higher among women who were not tested, then more than 28 untested women would have to be HIV positive for our overall estimate of sero-prevalence to be significantly different (≥0.9%). If all the women in the untested group had been tested and none were positive, the sero-prevalence would have been 0.64%, which is not significantly different from the sero-prevalence rate found in our study. We did not ask the 245 women who reported prior negative HIV testing how recently they had been tested; however, if their reports were accurate and they remained negative, the sero-prevalence rate would actually have been 0.68%, and potentially only 3 women missed the opportunity to prevent MTCT. Of note, since 1996, CMC has had a protocol for rapid HIV testing for women who present in labor and do not have previously documented HIV testing; however, this was a cross-sectional study, and we did not review the records to determine whether any of the women who were not tested as part of the study presented to CMC in labor and underwent testing at that time.

Looking Forward

Since this study’s completion in 2005, CMC has been able to expand on its original PPTCT protocol and offer ARV medications to all women who qualify based on their own CD4 count or World Health Organization (WHO) clinical stage or based on the need to prevent transmission to the baby, even if the woman does not require treatment for herself. With the support of NACO, women who test positive are offered CD4 count testing to determine whether they need treatment or prophylaxis only. Currently, first-line therapy for women with qualifying CD4 counts includes ZDV, lamivudine (3TC), and NVP. Those who require ARV medications only to prevent transmission are given either ZDV or NVP alone or ZDV plus single-dose NVP in labor followed by ZDV and 3TC for 1 week postpartum. HIV-positive women are encouraged to consider elective caesarian section to reduce transmission risk, as viral loads are only available for research purposes. All women who present in labor without documentation of an HIV status undergo rapid testing and, if positive, receive single-dose NVP followed by ZDV and 3TC for 1 week postpartum. All babies born to HIV-positive mothers receive a single dose of NVP soon after birth plus 6 weeks ZDV syrup. Nearly 30% of the HIV-positive women currently following in the ANC clinic are on ART either started during their current pregnancy or were already on therapy prior to becoming pregnant.

Although the government of India pledged to provide free ARV medications to Indians who met criteria for treatment starting April 2004, it is clear that many of the people who would benefit from this program were unaware of its existence. Since this study’s completion in 2005, the Indian government has undertaken a much broader campaign to notify its citizens of issues related to HIV, including ARV therapy. We hope that broad availability of ARV medications will not only improve the quality and length of life of HIV-positive people in India but also increase the willingness of general population to be tested as has been seen in other countries.17 An additional benefit of increased testing will be increased accuracy of sero-prevalence estimates across the entire population. It will be important to continue to assess the level of awareness of the population, particularly women of childbearing age, to ensure that adequate education is reaching them. Only with full awareness of the methods of prevention and treatment of HIV will Indian women and their families be able to make appropriate health decisions to protect themselves and their children from this deadly virus.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participants for their cooperation with interviews and testing, the staff at the Christian Medical College Main Hospital, CHAD, and RUHSA, and the department of virology for collecting and analyzing samples. In addition, the authors thank the staff of the department of biostatistics, particularly Mrs Sridevi and Mr Sathya Murthi, for their assistance in compiling and analyzing the study data.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: This study was supported by the Fogarty AIDS International Research and Training Program (2D43 TW000237) of Tufts and Brown University. Additional support for the Prevention of Parent to Child Transmission Program was provided by the National AIDS Control Organization, through the Tamil Nadu State AIDS Society. Jacqueline Firth received financial and logistical support from the Fogarty-Ellison International Clinical Research Training Program of Tufts and Brown Universities, sponsored by the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Reprints and permission: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Dandona L, Lakshmi V, Kumar GA, Dandona R. Is the HIV burden in India being overestimated? BMC Public Health. 2006;6:308. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barton-Knott S UNAIDS. Revised HIV Estimates Factsheet. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar R, Jha P, Arora P, et al. Trends in HIV-1 in young adults in south India from 2000 to 2004: a prevalence study. Lancet. 2006;367(9517):1164–1172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68435-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupte MD, Mehendale SM, Pandav CS, Paranjape RS, Kumar MS. HIV-1 in young adults in south India. Lancet. 2006;368(9530):114. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68993-9. author reply 115–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tamil Nadu State AIDS Control Society. The Tamil Nadu HIV Sentinel Surveillance Report-2005. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 6.John T, Bhushan N, Babu P, Seshadri L, Balasubramanium N, Jasper P. Prevalence of HIV infection in pregnant women in Vellore region. Ind J Med Res. 1993;97:227–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kang G, Samuel R, Vijayakumar T, et al. Community prevalence of antibodies to human immunodeficiency virus in rural and urban Vellore, Tamil Nadu. Natl Med J India. 2005;18(1):15–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National AIDS Control Organization. [Accessed September 27, 2008.];HIV Data: The Big Picture. http://www.nacoonline.org/Quick_Links/To_Read_More/

- 9.National AIDS Control Organization. National Baseline Behavioral Survey (BSS) among General Population, 2001. New Delhi: National AIDS Control Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.National AIDS Control Organization. National Baseline Behavioral Survey (BSS) among General Population, 2005. New Delhi: National AIDS Control Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown H, Vallabhaneni S, Solomon S, et al. Attitudes towards prenatal HIV testing and treatment among pregnant women in southern India. Int J STD AIDS. 2001;12(6):390–394. doi: 10.1258/0956462011923345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lionel J, Mathai M, Abraham O, Cherian T. Management of HIV infection in pregnancy: possible guidelines and their basis. Nat Med J India. 2003;16(2):94–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connor EM, Sperling RS, Gelber R, et al. Reduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(18):1173–1180. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411033311801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.The mode of delivery and the risk of vertical transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1—a meta-analysis of 15 prospective cohort studies. The International Perinatal HIV Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(13):977–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904013401301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. HIV/AIDS in Asia and the Pacific Region 2003, Annex 2: Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission. WHO Western Pacific and Southeast Asia; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas K, Thyagarajan S, Jeyaseelan L, et al. Community prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases and human immuno-deficiency virus infection in Tamil Nadu, India: a probability proportional to size cluster survey. Natl Med J India. 2002;15(3):135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levy N, Miksad R, Fein O. From treatment to prevention: the interplay between HIV/AIDS treatment availability and HIV/AIDS prevention programming in Khayelitsha, South Africa. J Urban Health. 2005;82(3):498–509. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]