Abstract

Background. Perioperative vascular function has been widely studied using noninvasive techniques that measure reactive hyperemia as a surrogate marker of vascular function. However, studies are limited to a static setting with patients tested at rest. We hypothesized that exercise would increase reactive hyperemia as measured by digital thermal monitoring (DTM) in association to patients' cardiometabolic risk. Methods. Thirty patients (58 ± 9 years) scheduled for noncardiac surgery were studied prospectively. Preoperatively, temperature rebound (TR) following upper arm cuff occlusion was measured before and 10 minutes after exercise. Data are presented as means ± SD. Statistical analysis utilized ANOVA and Fisher's exact test, with P values <0.05 regarded as significant. Results. Following exercise, TR-derived parameters increased significantly (absolute: 0.53 ± 0.95 versus 0.04 ± 0.42°C, P=0.04, and % change: 1.78 ± 3.29 versus 0.14 ± 1.27 %, P=0.03). All patients with preoperative cardiac risk factors had a change in TR (after/before exercise, ΔTR) with values falling in the lower two tertiles of the study population (ΔTR <1.1%). Conclusion. Exercise increased the reactive hyperemic response to ischemia. This dynamic response was blunted in patients with cardiac risk factors. The usability of this short-term effect for the preoperative assessment of endothelial function warrants further study.

1. Introduction

The physiological response of peripheral vasodilation during and shortly after exercise is affected by several factors. The vascular endothelium plays a central role in the regulation of vascular tone via nitric oxide, which has a key role in endothelial function, and is involved in exercise-induced vasodilation [1, 2]. Impaired endothelial function is promoted by injury from mechanical forces and processes related to cardiovascular risk factors including ageing [3], hypertension [4], dyslipidaemia [5], impaired fasting glucose [6, 7], insulin resistance [8], hyperhomocysteinemia [9], smoking [10, 11], or acute postprandial hypertriglyceridemia [12]. With an increasing incidence of these risk factors among the patient population presenting preoperatively, noninvasive assessment of endothelial-dependent vascular function in response to exercise might be a diagnostic tool gaining importance in the preoperative risk assessment.

Despite advances in perioperative care, patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery continue to experience a high incidence of postoperative morbidity (15–36%) and mortality (4.8–10.9%, e.g., following pneumonectomy), with increased health care expenditure [13, 14]. Cardiovascular risk factors predispose to perioperative morbidity and mortality, with evidence that patients with microvascular dysfunction undergoing cardiovascular interventions are at increased risk for postoperative complications [15, 16].

Given that the noncardiovascular surgical population increasingly presents with multiple cardiovascular risk factors [17], there is need to explore the role of endothelial dysfunction in this population from a clinical point of view. Recent studies investigating DTM have shown that impaired vascular reactivity correlated with the extent of myocardial perfusion defect and was found in patients with coronary artery disease, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes mellitus [18, 19]. It is increasingly recognized as a diagnostic tool for cardiovascular risk assessment [20–22].

The noninvasive assessment of reactive hyperemia in response to exercise, as a surrogate marker of endothelial-dependent vascular function, has not been described in the literature at this point. Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that acute exercise would increase reactive hyperemia regardless of changes in blood pressure, heart rate, and body temperature (primary endpoint). In addition, we tested the hypothesis that a lack of reactive hyperemia increase after exercise would correlate with preoperative cardiovascular risk factors (secondary endpoint).

2. Methods

2.1. Subjects

Following IRB approval (The University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, study protocol no. 2003-0434), thirty consecutive patients scheduled for major noncardiac surgery (esophagectomy or major lung surgery, e.g., lobectomy or pneumonectomy) were prospectively enrolled into this observational trial. Exclusion criteria were any condition that deemed a patient unsatisfactory for surgery after the preanesthetic evaluation. Patients were evaluated with standard preoperative risk scores, including the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Physical Status Classification System and modified Lee Cardiac Risk Index [23, 24].

2.2. Study Endpoints

The primary endpoint of this pilot study investigated whether acute exercise would increase reactive hyperemia, a surrogate marker of vascular function, and that this effect would be blunted in the presence of preoperative cardiovascular risk factors (i.e., coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity).

2.3. Measurement of Reactive Hyperemia

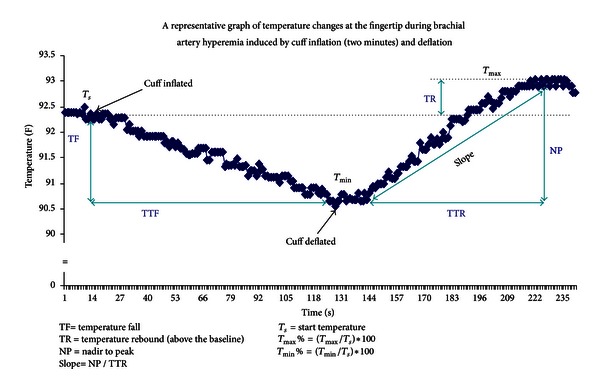

To ensure consistency, all measurements of reactive hyperemia were performed within one week of scheduled surgery. Measurements were performed before and 10 minutes after exercise in a quiet dimmed room at a controlled ambient temperature (20–25°C) using a VENDYS 5000BC Digital Thermal Monitoring (DTM) system (Endothelix, Inc., Houston, TX, USA). This FDA approved device consists of a computer-based thermometry system (0.006°C thermal resolution), with two special thermocouple fingertip probes designed to minimize the area of skin-probe contact and fingertip pressure. A standard sphygmomanometer cuff and a compressor unit to control cuff inflation and deflation is included to facilitate the occlusion-hyperemia protocol. The test is conducted with the patient at rest for 30 minutes in the supine position, in a quiet, dimmed room with ambient temperature of 24°C to 26°C. VENDYS DTM probes are affixed to the index finger of each hand and after a period of stabilization of basal skin temperature (defined as stabilization within a 0.05°C threshold) the temperature is measured in the index fingers of both hands (of which the right arm only is subjected to occlusion-hyperemia) with an automated, operator-independent protocol. The right upper arm cuff is rapidly inflated to ≥50 mmHg above systolic pressure for 2 minutes and then rapidly deflated to invoke reactive hyperemia distally. Thermal tracings are measured continuously and digitized automatically using a computer-based thermometry system with 0.006°C thermal resolution. Dual channel temperature data is simultaneously acquired at a 1 Hz sample rate. Figure 1 shows a representative example of a temperature-time trace and the primary DTM-derived measures, related to thermal debt and recovery that were recorded and calculated.

Figure 1.

Representative example of a temperature-time trace in response to occlusion-hyperemia.

3. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing (CPET)

Prior to exercise, baseline vitals (heart rate, blood pressure, pulse oximetry, and ECG) and static pulmonary function tests (forced expiratory volume at 1 second, forced vital capacity, and maximal voluntary ventilation) were recorded for all patients. CPET was then performed as a multistage incremental “ramp workload” study using a cycle ergometer and a metabolic cart with standardized exercise software (Medgraphic Cardio-2CP system, Medical Graphics Corporation, St. Paul, MN, USA) for breath-by-breath analysis of gas exchange.

An initial acclimation period consisted of breath-by-breath gas exchange analysis performed in the supine, resting position for five minutes. After acclimation the patient pedaled at 60 rpm with minimal resistance for three minutes (unloaded work). After three minutes, loaded work (increasing pedal resistance, watts per minute) followed a standardized ramp protocol to maximal symptom limited exertion that typically lasted 9–12 minutes. Exercise was terminated by the study patient or by the study investigator if symptoms of cardiovascular, pulmonary distress, and/or fatigue were observed. To ensure consistency, exercise above the anerobic threshold was required for inclusion into the study. Anerobic threshold (AT, mL/kg/min) was defined as the VO2 at the inflection point as determined by the modified V-slope method of plotting carbon dioxide excretion (VCO2) against oxygen uptake (VO2) during increasing exercise intensity, as described by Wasserman et al. [25]. Gas exchange analysis recorded oxygen consumption (VO2, mL/kg/min) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2, mL/kg/min) at all phases of exercise.

3.1. Statistical Analysis

The study sample size determination was based on data from a previous study by Harris et al. who enrolled nine patients to detect an increase of reactive hyperemia, as measured by flow-mediated dilation of the brachial artery, immediately after 45 min of exercise on a treadmill at 50% of their VO2 peak. We calculated that a sample of thirty patients would need to be enrolled to achieve 80% power to detect a log-linear trend in the primary endpoint assuming that the percentage increase of reactive hyperemia after exercise, as measured by TR, was 50 percentage points. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the patients' demographic, clinical, and TR measures. The relative changes from baseline (before exercise) and after-exercise (10 minutes after peak exercise) were analyzed using repeated measures (ANOVA) and Wilcoxon signed ranks test.

Fisher's exact test was used to analyze for an association of perioperative variables—including patients' comorbidities (i.e., obesity, abdominal obesity, coronary artery disease, and Modified Lee Cardiac Risk Index) with TR measures when tertiles were used as cutoff points. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and S-Plus (version 8; Insightful Corp., Seattle, WA, USA).

4. Results

4.1. Clinical and Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants

Thirty patients (18 males and 11 females) with mean age of 58 ± 10 years scheduled for major noncardiac surgery were enrolled in the study. Twenty-eight (93%) patients had an increased perioperative risk with an ASA score >2; thirteen (46%) patients had cardiovascular risk factors, for example, hypertension and dyslipidemia; and twenty-one (70%) patients were current smokers. Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics.

| n | Mean (±SD) | Median (range) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 30 | 58 (±9.93) | 59 (45–70) |

| Height, m | 30 | 1.70 (±0.11) | 1.70 |

| Weight, kg | 30 | 83 (±18.62) | 81 |

| Waist, cm | 28 | 104 (±38.48) | 98 |

| BMI, (kg/m)2 | 30 | 28 (±4.76) | 28 |

| PreOp hemoglobin, mg/dL | 30 | 13 (±1.16) | 13 |

| PreOp fasting glucose, mg/dL | 30 | 103 (±24.63) | 100 |

| PreOp creatinine, mg/dL | 28 | 1.03 (±0.24) | 1.00 |

| Length of hospital stay, d | 30 | 12 (±13.91) | 7 |

| Length of ICU stay, d | 30 | 4 (±13.39) | 0 |

|

| |||

| n (%) | |||

|

| |||

| Sex, female | 11 (37) | ||

| Obesity, n (%) | 10 (33) | ||

| Abdominal obesity, n (%) | 13 (46) | ||

| Smoker, n (%) | 21 (70) | ||

| Coronary artery disease**, n (%) | 1 (3) | ||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 13 (43) | ||

| Diabetes, n (%) | 4 (13) | ||

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 13 (43) | ||

| Statin therapy, n (%) | 5 (17) | ||

| β-Blocker therapy, n (%) | 6 (20) | ||

| ACE-inhibitor therapy, n (%) | 4 (13) | ||

| ASA risk score > 2, n (%) | 28 (93) | ||

| Lee Cardiac Risk Index > 2, n (%) | 3 (10) | ||

| Chemotherapy, n (%) | 13 (43) | ||

| Radiation therapy, n (%) | 10 (33) | ||

**Patient status after myocardial infarction (with or without intervention).

4.2. Reactive Hyperemia (TR) before and after Exercise

Table 2 summarizes the vital signs (heart rate and blood pressure) and the reactive hyperemia measures before and after exercise. The heart rate was significantly increased 10 min after exercise when compared to baseline (mean: 75 ± 10.58 versus 76 ± 19.88 min−1; P = 0.021). There were no differences in blood pressure before and after exercise. The starting temperature at the beginning of the reactive hyperemia measurement did not differ before and after exercise (mean: 32.84 ± 1.78 versus 32.23 ± 2.01°C; P = 0.147).

Table 2.

Reactive hyperemia (TR) before and after exercise.

| Before exercise | After exercise (10 min after) | P values* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Std deviation | N | Mean | Std deviation | ||

| Starting temperature (°C) | 30 | 32.84 | 1.78 | 30 | 32.23 | 2.01 | 0.147 |

| Temperature rebound (TR°C) | 30 | 0.04 | 0.42 | 30 | 0.53 | 0.95 | 0.035* |

| Temperature rebound (TR%) | 30 | 0.14 | 1.27 | 30 | 1.78 | 3.29 | 0.033* |

| Area under curve after 15 sec | 30 | 14.89 | 4.70 | 30 | 11.92 | 5.26 | 0.019* |

| Area under curve after 30 sec | 30 | 29.01 | 9.04 | 30 | 23.29 | 10.23 | 0.017* |

| Area under curve after 45 sec | 30 | 41.50 | 12.86 | 30 | 33.34 | 14.53 | 0.017* |

| Area under curve after 60 sec | 30 | 52.11 | 16.15 | 30 | 41.85 | 18.12 | 0.020* |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 27 | 75 | 10.58 | 28 | 76 | 19.88 | 0.021 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 27 | 128 | 16.94 | 28 | 132 | 16.35 | 0.216 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 27 | 76 | 6.09 | 28 | 79 | 9.06 | 0.081 |

| Mean blood pressure (mmHg) | 27 | 94 | 11.59 | 28 | 98 | 2.01 | 0.094 |

*Wilcoxon signed ranks test.

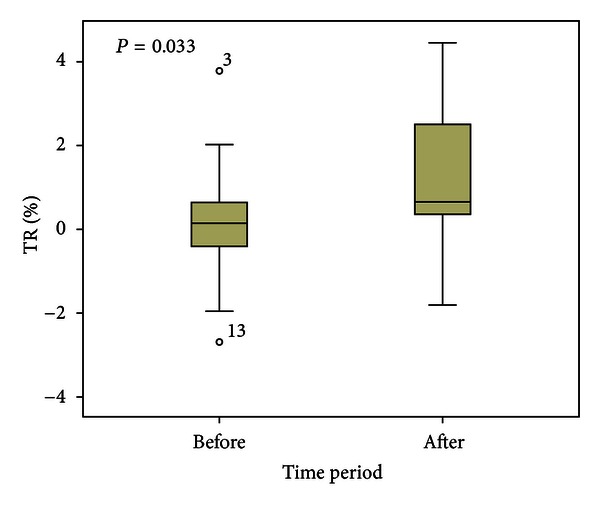

Reactive hyperemia was significantly increased 10 min after exercise with an absolute TR increase of 0.04 ± 0.42 versus 0.53 ± 0.95°C, P = 0.035 and a relative TR increase of 0.14 ± 1.27 versus 1.78 ± 3.29%, P = 0.033 (Figure 2). Area under the curve (AUC) of the TR slope was significantly lower after exercise with AUC 15 sec: 14.89 ± 4.70 versus 11.92 ± 5.26, P = 0.019; AUC 30 sec: 29.01 ± 9.04 versus 23.29 ± 10.23, P = 0.017; AUC 45 sec: 41.50 ± 12.86 versus 33.34 ± 14.53, P = 0.017; and AUC 60 sec: 52.11 ± 16.15 versus 41.85 ± 18.12, P = 0.020.

Figure 2.

Increase of reactive hyperemia (temperature rebound, TR%) 10 minutes after peak exercise.

There was no association between clinical characteristics and low TR values (2 lower tertiles) when compared to high TR values (upper tertile) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Clinical characteristics and tertiles of TR % change after exercise (pre-/postexercise difference).

| n | Lower 2 tertiles (<−0.0952 and <1.1162) |

Upper tertiles (≥1.1162) |

P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 30 | 57.5 ± 11.3 | 59.1 ± 6.7 | 0.685 |

| Sex, n (%) female | 11 | 6 (55) | 5 (45) | 0.425 |

| Height, m | 30 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 0.589 |

| Weight, kg | 30 | 84.5 ± 19.3 | 79.5 ± 17.8 | 0.501 |

| Waist, cm | 28 | 107.5 ± 46.2 | 95.9 ± 10.1 | 0.465 |

| BMI, (kg/m)2 | 30 | 28.8 ± 5.4 | 27.7 ± 3.3 | 0.567 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 10 | 8 (80) | 2 (20) | 0.419 |

| Abdominal obesity, n (%) | 13 | 8 (62) | 5 (38) | 0.505 |

| Smoker, n (%) | 21 | 12 (57) | 9 (43) | 0.204 |

| Coronary artery disease**, n (%) | 1 | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 13 | 11 (85) | 2 (15) | 0.119 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 4 | 4 (100) | 0 (0) | 0.272 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 13 | 8 (62) | 5 (38) | 0.705 |

| Statin therapy, n (%) | 5 | 3 (60) | 2 (40) | 1.000 |

| β-Blocker therapy, n (%) | 6 | 6 (100) | 0 (0) | 0.074 |

| Aspirin therapy, n (%) | 5 | 5 (100) | 0 (0) | 0.140 |

| ACE-inhibitor therapy, n (%) | 4 | 3 (75) | 1 (25) | 1.000 |

| ASA risk score > 2, n (%) | 28 | 19 (68) | 9 (32) | 0.615 |

| Lee Cardiac Risk Index > 2, n (%) | 3 | 3 (100) | 0 (0) | 0.107 |

| Chemotherapy, n (%) | 13 | 7 (54) | 6 (46) | 0.255 |

| Radiation therapy, n (%) | 10 | 7 (70) | 3 (30) | 0.101 |

| PreOp echo/EF, % | 17 | 61.4 ± 3.8 | 62.4 ± 6.9 | 0.709 |

| PreOp hemoglobin, mg/dL | 30 | 13.3 ± 1.0 | 13.5 ± 1.4 | 0.705 |

| PreOp fasting glucose, mg/dL | 30 | 106.7 ± 28.6 | 95.8 ± 12.0 | 0.260 |

| PreOp creatinine, mg/dL | 28 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.509 |

| Length of hospital stay, d | 30 | 11.2 ± 11.7 | 12.6 ± 18.32 | 0.800 |

| Length of ICU Stay, d | 30 | 2.4 ± 9.0 | 6.3 ± 19.9 | 0.462 |

*Fisher's exact test.

**Patient status after myocardial infarction (with or without intervention).

5. Discussion

The principal finding of the present study is that a single episode of acute exercise above the anerobic threshold enhanced the reactive hyperemia, a surrogate marker of endothelial function. These results imply that a short period of exercise enhances cutaneous perfusion and is associated with an increase in the release and/or bioactivity of endogenous vasodilatative mediators (e.g., NO) in the endothelial cells of skin vasculature. We were able to measure this short-term effect with the use of digital thermal monitoring (DTM) of temperature rebound (TR), which provides a noninvasive assessment of vascular function.

However, the diagnostic value of our findings in terms of preoperative assessment of endothelial dysfunction warrants further research. Although we found that patients with preoperative cardiac risk factors and postoperative complications were within the lower 2 tertiles of the study population (ΔTR < 1.1%), this observation needs to be validated in a larger patient population.

In agreement with our findings, previous work has demonstrated that acute exercise increases skin blood flow and cutaneous vascular conductance accompanied by enhanced plasma NO metabolite levels and acetylcholine-induced cutaneous perfusion [26]. These authors suggested that endothelium-dependent dilation in skin vasculature is enhanced by moderate exercise training and reversed to the pretraining state with detraining.

Furthermore, our observations suggest that this effect can be reproduced by a single episode of exercise above the anerobic threshold increasing the aerobic capacity and vascular responsiveness to acute exercise.

In contrast, a previous study investigating on the effect of 6 months of aerobic exercise in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus was not able to show an improvement of microvascular dysfunction [27]. The authors interpreted their negative results with the hypothesis that micro- and macrocirculation respond differently to the exercise stimulus. We were able to observe a significant increase of reactive hyperemia after a short exercise stimulus. However, it remains unclear how long this effect would have lasted on and we suggest that our observed physiological response to exercise has rather diagnostic than therapeutic value.

Our study has implications for preoperative assessment of endothelial function, as the observed increased reactive hyperemic signal shortly after exercise may serve as a diagnostic tool. Impairment of endothelial function is a precursor for cardiovascular disease and precedes the morphological changes associated with atherosclerosis in the blood vessels [28] and the clinical manifestations of its associated complications (e.g., myocardial infarction, stroke) [29, 30]. Furthermore, any transient inflammatory burden or a systemic inflammatory state also adversely affects endothelium-dependent vascular function with consequent increase in risk for cardiovascular complications [31, 32]. In the perioperative context, inflammatory mediator release associated with surgical trauma has been shown to impair vascular function and correlate with both the duration and extent of major surgery [31–35]. This effect may be additive to the underlying endothelial dysfunction that is inherent in certain surgical patients as a result of their preoperative comorbidity burden and thus plays a significant role in certain perioperative complications (e.g., perioperative myocardial infarction, poor wound healing, ALI, and sepsis) [33, 35].

6. Conclusions

Based on our results, we suggest that the preoperative assessment of endothelial function using reactive hyperemia in response to exercise gains clinical importance as a potential risk assessment tool in the prevention of perioperative complications and should be further studied in a larger patient population.

Disclosure

The meeting at which the work has been presented is American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) Meeting, October 21, 2008, Orlando, FL, USA.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Acknowledgment

This study was supported by IARS Grant funding.

References

- 1.Maxwell AJ, Schauble E, Bernstein D, Cooke JP. Limb blood flow during exercise is dependent on nitric oxide. Circulation. 1998;98(4):369–374. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.4.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vane JR, Anggard EE, Botting RM. Regulatory functions of the vascular endothelium. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1990;323(1):27–36. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007053230106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Spiegelhalter DJ, Georgakopoulos D, Robinson J, Deanfield JE. Aging is associated with endothelial dysfunction in healthy men years before the age-related decline in women. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1994;24(2):471–476. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panza JA, Quyyumi AA, Brush JE, Epstein SE. Abnormal endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation in patients with essential hypertension. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1990;323(1):22–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199007053230105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chowienczyk PJ, Watts GF, Cockcroft JR, Ritter JM. Impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilation of forearm resistance vessels in hypercholesterolaemia. Lancet. 1992;340(8833):1430–1432. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92621-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawano H, Motoyama T, Hirashima O, et al. Hyperglycemia rapidly suppresses flow-mediated endothelium-dependent vasodilation of brachial artery. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1999;34(1):146–154. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00168-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams SB, Goldfine AB, Timimi FK, et al. Acute hyperglycemia attenuates endothelium-dependent vasodilation in humans in vivo. Circulation. 1998;97(17):1695–1701. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.17.1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arcaro G, Cretti A, Balzano S, et al. Insulin causes endothelial dysfunction in humans: sites and mechanisms. Circulation. 2002;105(5):576–582. doi: 10.1161/hc0502.103333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tawakol A, Omland T, Gerhard M, Wu JT, Creager MA. Hyperhomocyst(e)inemia is associated with impaired endothelium- dependent vasodilation in humans. Circulation. 1997;95(5):1119–1121. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.5.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Celermajer DS, Adams MR, Clarkson P, et al. Passive smoking and impaired endothelium-dependent arterial dilatation in healthy young adults. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1996;334(3):150–154. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199601183340303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Celermajer DS, Sorensen KE, Georgakopoulos D, et al. Cigarette smoking is associated with dose-related and potentially reversible impairment of endothelium-dependent dilation in healthy young adults. Circulation. 1993;88(5):2149–2155. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.5.2149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaenzer H, Sturm W, Neumayr G, et al. Pronounced postprandial lipemia impairs endothelium-dependent dilation of the brachial artery in men. Cardiovascular Research. 2001;52(3):509–516. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00427-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Devereaux P. Association between postoperative troponin levels and 30-day mortality among patients undergoing noncardiac surgery (VISION Study) The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2012;307:2295–2304. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaporciyan AA, Merriman KW, Ece F, et al. Incidence of major pulmonary morbidity after pneumonectomy: association with timing of smoking cessation. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 2002;73(2):420–426. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)03443-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akcakoyun M, Kargin R, Tanalp AC, et al. Predictive value of noninvasively determined endothelial dysfunction for long-term cardiovascular events and restenosis in patients undergoing coronary stent implantation: A Prospective Study. Coronary Artery Disease. 2008;19(5):337–343. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e328301ba8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang AL, Silver AE, Shvenke E, et al. Predictive value of reactive hyperemia for cardiovascular events in patients with peripheral arterial disease undergoing vascular surgery. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2007;27(10):2113–2119. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.147322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathieu P. Abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome: a surgeon’s perspective. The Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2008;24:19D–23D. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(08)71045-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahmadi N, Hajsadeghi F, Gul K, et al. Vascular function measured by fingertip thermal reactivity is impaired in patients with metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus. Journal of Clinical Hypertension. 2009;11(11):678–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-4572.2009.00058.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ahmadi N, Nabavi V, Nuguri V, et al. Low fingertip temperature rebound measured by digital thermal monitoring strongly correlates with the presence and extent of coronary artery disease diagnosed by 64-slice multi-detector computed tomography. International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging. 2009;25(7):725–738. doi: 10.1007/s10554-009-9476-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmadi N, Hajsadeghi F, Gul K, et al. Relations between digital thermal monitoring of vascular function, the Framingham risk score, and coronary artery calcium score. Journal of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. 2008;2(6):382–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gul KM, Ahmadi N, Wang Z, et al. Digital thermal monitoring of vascular function: a novel tool to improve cardiovascular risk assessment. Vascular Medicine. 2009;14(2):143–148. doi: 10.1177/1358863X08098850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van Der Wall EE, Schuijf JD, Bax JJ, Jukema JW, Schalij MJ. Fingertip digital thermal monitoring: a fingerprint for cardiovascular disease? International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging. 2010;26(2):249–252. doi: 10.1007/s10554-009-9552-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dripps RD, Lamont A, Eckenhoff JE. The role of anesthesia in surgical mortality. The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1961;178:261–266. doi: 10.1001/jama.1961.03040420001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee TH, Marcantonio ER, Mangione CM, et al. Derivation and prospective validation of a simple index for prediction of cardiac risk of major noncardiac surgery. Circulation. 1999;100(10):1043–1049. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.10.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wasserman K, Hansen JE, Sue DV, Whipp BJ. Principles of Exercise Testing and Interpretation. Philadelphia, Pa, USA: Lea & Febiger; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang JS. Effects of exercise training and detraining on cutaneous microvascular function in man: the regulatory role of endothelium-dependent dilation in skin vasculature. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2005;93(4):429–434. doi: 10.1007/s00421-004-1176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Middlebrooke AR, Elston LM, MacLeod KM, et al. Six months of aerobic exercise does not improve microvascular function in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2006;49(10):2263–2271. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0361-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heitzer T, Schlinzig T, Krohn K, Meinertz T, Münzel T. Endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2001;104(22):2673–2678. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993;362(6423):801–809. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Werns SW, Walton JA, Hsia HH, Nabel EG, Sanz ML, Pitt B. Evidence of endothelial dysfunction in angiographically normal coronary arteries of patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1989;79(2):287–291. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tonetti MS, D'Aiuto F, Nibali L, et al. Treatment of periodontitis and endothelial function. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;356:911–920. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vallance P, Collier J, Bhagat K. Infection, inflammation, and infarction: does acute endothelial dysfunction provide a link? The Lancet. 1997;349(9062):1391–1392. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09424-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burnham E, Moss M. Progenitor cells in acute lung injury. Minerva Anestesiologica. 2006;72(6):369–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hunt BJ, Jurd KM, Blann AD, Lip GYH. Relation between endothelial-cell activation and infection, inflammation, and infarction. The Lancet. 1997;350(9073):293–294. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)62261-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rafat N, Hanusch C, Brinkkoetter PT, et al. Increased circulating endothelial progenitor cells in septic patients: correlation with survival. Critical Care Medicine. 2007;35(7):1677–1684. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000269034.86817.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]