Abstract

Objective

To identify predictors of becoming eating disordered among adolescents.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Self-report questionnaires.

Subjects

Girls (n=6916) and boys (n=5618), aged 9 to 15 years at baseline, in the ongoing Growing Up Today Study (GUTS).

Main Exposures

Parent, peer, and media influences.

Main Outcome Measures

Onset of starting to binge eat or purge (ie, vomiting or using laxatives) at least weekly.

Results

During 7 years of follow-up, 4.3% of female subjects and 2.3% of male subjects (hereafter referred to as “females” and “males”) started to binge eat and 5.3% of females and 0.8% of males started to purge to control their weight. Few participants started to both binge eat and purge. Rates and risk factors varied by sex and age group (<14 vs ≥14 years). Females younger than 14 years whose mothers had a history of an eating disorder were nearly 3 times more likely than their peers to start purging at least weekly (odds ratio, 2.8; 95% confidence interval, 1.3–5.9); however, maternal history of an eating disorder was unrelated to risk of starting to binge eat or purge in older adolescent females. Frequent dieting and trying to look like persons in the media were independent predictors of binge eating in females of all ages. In males, negative comments about weight by fathers was predictive of starting to binge at least weekly.

Conclusions

Risk factors for the development of binge eating and purging differ by sex and by age group in females. Maternal history of an eating disorder is a risk factor only in younger adolescent females.

Concerns about weight and body shape are common in preadolescents and adolescents1,2 and are probably related to the development of unhealthy weight control behaviors and binge eating. However, because of the lack of large prospective studies of non–treatment-seeking samples, little is known with certainty about the development of disordered eating (eg, engaging in bulimic behaviors) or eating disorders.

Although there have not been many large prospective studies of disordered eating (ie, engaging in binge eating or purging) or full-criteria eating disorders3 among non–treatment-seeking samples, a variety of risk factors for disordered eating and eating disorders have been proposed. The support for some of these purported risk factors is stronger than for others.4 The risk factors with the strongest support, which are those that have been identified in at least 2 prospective studies, as well as for those factors that do not change with time and have been identified in at least 2 cross-sectional studies, include age (adolescence and early adulthood being the periods of highest risk),4 female sex, frequent dieting,5,6 preoccupation with thinness,7,8 teasing about body shape or weight,9,10 body dissatisfaction and weight concerns,11,12 comorbid psychiatric diagnoses,6,13 perceived peer and media pressure to be thin,1,14,15 and family history of an eating disorder.16 However, these suspected risk factors have rarely been investigated in multivariate models that controlled for at least several of the other suspected risk factors. Thus, it remains unclear whether all are true independent risk factors. Moreover, data are lacking about whether these suspected risk factors apply to both sexes.

The objective of the present investigation was to assess whether various suspected risk factors for eating disorders are independently associated with starting to frequently binge eat, purge (vomiting or using laxatives to control weight), or both binge eat and purge during 7 years in more than 12 500 male and female subjects in the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS), who were initially 9 to 15 years of age.

METHODS

GUTS was established in 1996 by recruiting children of women participating in the Nurses’ Health Study II, an ongoing study that was established in 1989 and consists of 116 608 female nurses, who were 25 to 43 years of age at enrollment. Follow-up questionnaires have been sent to participants every 2 years since 1989. Additional details about the cohort have been reported previously.17 Using data from the Nurses’ Health Study II, we identified mothers who had children aged 9 to 14 years. We wrote a detailed letter to the mothers, explaining the purpose of GUTS and seeking parental consent to enroll their children. Children whose mothers gave consent to invite them to participate were mailed an invitation letter and a questionnaire. Additional details have been reported previously.2 Approximately 68% of the females (n=9039) and 58% of the males (n=7843) returned completed questionnaires, thereby assenting to participate in the cohort. The participants have been sent questionnaires every 12 to 18 months. The participants were children and adolescents (aged 9–15 years) at baseline and became older adolescents and adults (aged 16–22 years) during the course of the study. Participants are referred to as males and females because these terms are appropriate for all age groups. In addition, in 2004, a questionnaire was sent to their mothers. The study was approved by the Human Subjects Committee at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the analyses presented herein were approved by the institutional review boards at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Children’s Hospital Boston, both in Boston, Massachusetts.

SAMPLE

Participants were excluded from the analysis if their mother did not answer the 2004 mothers’ questionnaire (2007 females and 1997 males), they did not return at least 1 follow-up questionnaire between 1997 and 2003 (115 females and 228 males), or they were younger than 9 years at baseline (1 female); thus, there were 6916 females and 5618 males for analyses. Participants who reported purging at baseline (28 females and 12 males) or were missing information about purging during follow-up (49 females and 54 males) were excluded from the analysis of the incidence of purging at least weekly; thus, 6839 females and 5552 males were included in the purging analysis. Participants who reported binge eating at baseline (52 females and 18 males) or were missing information about binge eating during follow-up (41 females and 51 males) were excluded from the analysis of the incidence of binge eating at least weekly; thus, 6823 females and 5549 males were included in the bingeing analysis. In the analyses identifying risk factors for starting to binge eat or purge, we used the deletion approach to handle the missing data. Thus, participants were further excluded if they were missing information about the outcome or any of the exposures at all time points, thereby reducing the sample to 6219 females and 4869 males in the final purging analyses and 6185 females and 4902 males in the final binge eating analyses.

MEASUREMENTS

Questionnaires Completed by GUTS Participants

During September 1, 1996, to November 11, 2003, GUTS participants received a questionnaire every 12 to 18 months that assessed a variety of factors such as self-reported weight, height, and age at menarche (females only). Body mass index (weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) was calculated using self-reported weight and height. Children were classified as overweight or obese on the basis of the International Obesity Task Force cutoff points,18 which are age- and sex-specific and provide comparability in assessing overweight and obesity from adolescence to adulthood. Questions about weight concerns and influences on perception of weight were assessed with the McKnight Risk Factor Survey (MRFS).19 Males are more likely than females to focus on wanting to increase muscle tone rather than being thin14,20,21; thus, to make the MRFS19 questions appropriate for males, the questions on thinness were replaced with questions about the importance of not being fat or desiring to not be fat. For the analysis, the MRFS questions were dichotomized. Thinness or lack of fatness was considered very important (to parent or peer) if the child indicated the degree of importance as “a lot” or “totally.” Females and males were considered to be making a lot of effort to look like females/males in the media if they responded “a lot” or “totally” to the question, “In the past year, how much effort have you made to look like the girls or women (boys or men) you see on television, in movies, or in magazines?”

Weight control behaviors were assessed with questions adapted from the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System questionnaire.22 Dieting was assessed with the question, “During the past year, how often did you diet to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight?” Children who reported that they had dieted to lose or maintain weight “once a week,” “2 to 6 times per week,” or “every day” were classified as frequent dieters, and children who reported that they had dieted “less than once a month” or “1 to 3 times a month” were classified as infrequent dieters. Purging was assessed with 2 questions: “During the past year, how often did you make yourself throw up to keep from gaining weight?” and “During the past year, how often did you take laxatives to keep from gaining weight?” Binge eating was assessed with a 2-part question. Participants were first asked about the frequency during the past year of eating a very large amount of food. Children who reported at least occasional episodes of overeating were directed to a follow-up question that asked whether they felt out of control during these episodes, like they could not stop eating even if they wanted to stop. Binge eating was defined as eating a very large amount of food in a short amount of time at least monthly and feeling out of control during the eating episode. Both the binge eating and purging questions have been validated in the GUTS cohort. Among the females, the specificity and negative predictive values of self-reported binge eating and purging were high, demonstrating that the questionnaire was an excellent tool for identifying females who did not purge.23 There were too few cases among the males to assess sensitivity, specificity, or predictive values with adequate certainty.

Questionnaires Completed by Mothers of GUTS Participants

In 2004, the mothers were sent a brief questionnaire that included questions about whether anyone in the family has or has had an eating disorder and whether anyone has been treated for an eating disorder. The response options were no one in the family, the mother, the child in GUTS, or another family member. From this information, 2 binary questions were created for the analysis; one was an indicator for the mother having an eating disorder and the other was an indicator for the mother having received treatment for an eating disorder.

MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES

The main outcome measures were starting to binge eat at least weekly, starting to purge at least weekly, and starting to engage in both binge eating and purging at least weekly.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We modeled the log-odds of the hazard rate for 3 different outcomes, that is, starting to binge eat, starting to purge, and starting to binge eat and purge, as a function of predictors that included age group, dieting frequency, age at menarche (females only), maternal history of an eating disorder, and various predictors from the MRFS. Predictors were lagged so that outcomes at a given time point were modeled as a function of predictors from the previous time point. Teasing was modeled as ever having been teased any time between baseline and the previous time point. The models were fitted using generalized estimating equations with an independence working covariance matrix, to address the dependence between children of the same mother. The analyses were performed using commercially available software (PROC GENMOD, version 8.2; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

The analyses were stratified by sex. Age (<14 vs ≥14 years), dieting, and maternal history of an eating disorder were included in all statistical models for both sexes. However, among the females, infrequent and frequent dieting were modeled as distinct categories, whereas among the males, infrequent and frequent dieting were combined into a single dieting category because not many males dieted frequently. Other predictors were included in the model if they remained at least marginally significant (P<.10) after controlling for age group, dieting, and maternal history of an eating disorder. Weight status, concern about weight, menarcheal status, body dissatisfaction, negative comments about weight by males, negative comments about weight by females, negative comments about weight by mothers, negative comments about weight by fathers, importance of thinness or not being fat to mothers, importance of thinness or not being fat to fathers, importance of thinness to peers, trying to look like persons in the media, and the mother having received treatment for an eating disorder were considered possible predictors. In addition, among the males, but not the females, height was predictive of starting to binge eat and was, therefore, included in the analysis. For the females, interactions by age group were included if there was some evidence of effect modification by age (younger [<14 years] vs older [≥14 years] adolescents). Interactions were retained if there was an association only in 1 age group or the difference in the point estimates between the 2 groups was larger than 1 (ie, relative risk,1.0 vs 2.0). For the males, effect modification by age was not explored because of lack of statistical power.

RESULTS

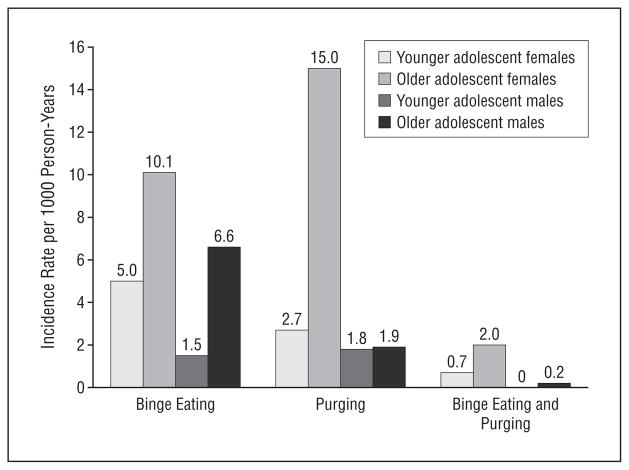

At baseline, the mean age of the participants was approximately 12 years (Table 1). During 7 years of follow-up, 10.3% of the females and 3.0% of the males started to binge eat or purge (vomiting or using laxatives) at least weekly to control their weight. Among the females, the cumulative incidence of binge eating (4.3%) was slightly lower than the incidence of purging (5.3%), whereas among the males, binge eating (2.1%) was more common than purging (0.8%). In both sexes, only a small percentage of the incident cases engaged in both binge eating and purging. Among the females, but not the males, the incidence rates for starting to purge rose markedly between younger adolescents and older adolescents, whereas among both males and females, the incidence rates for binge eating were higher among older adolescents than younger adolescents (Figure).

Table 1.

Baseline Data in Adolescents in GUTS

| Variable | Females (n=6916) | Males (n=5618) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 12.0 (1.6) | 11.9 (1.6) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 19.0 (3.3) | 19.1 (3.3) |

| Overweight or obese, % | 19.8 | 23.2 |

| Dieting, % | ||

| Infrequently | 22.4 | 12.1 |

| Frequently | 7.1 | 4.1 |

| High level of concern about weight, % | 9.0 | 4.1 |

| Making a lot of effort to look like same-sex persons in the media, % | 7.0 | 2.9 |

| Mother had or has an eating disorder, % | 4.3 | 3.8 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); GUTS, Growing Up Today Study.

Figure.

Incidence of beginning to engage in disordered eating at least weekly among younger and older adolescents in the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS) (1996–2003).

BINGE EATING

Among the females, frequent dieting, high level of concern about weight, and trying to look like same-sex persons in the media were predictive of increased risk of starting to binge eat frequently (Table 2). Maternal history of an eating disorder was not significantly related to risk among females or males. However, there was a suggestion among the females that negative comments about weight by males, importance of weight to fathers, and importance of weight to peers were associated with an increased risk of starting to binge eat weekly (Table 2). After controlling for dieting, being overweight was not associated with an increased risk of starting to binge eat (data not shown). Among males, a high level of concern with weight and negative comments about weight by fathers were both significant predictors of starting to binge eat at least weekly (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate Analysis for Predictors of Starting to Binge Eat at Least Weekly Between 1996 and 2003 Among Females and Males in GUTSa

| Variable | Females (n=6185)

|

Males (n=4902)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Preadolescent vs adolescent | 1.0 | 0.2–4.0 | 0.5 | 0.3–1.0 |

| Postmenarche vs premenarche | ||||

| Girls <14 y | 1.6 | 1.0–2.6 | … | … |

| Females ≥14 y | 1.6 | 0.4–6.1 | … | … |

| Height, in | … | … | 1.1 | 1.0–1.2 |

| Infrequent dieter vs nondieter | 1.1 | 0.7–1.7 | … | … |

| Frequent dieter vs nondieter | 2.2 | 1.4–3.7 | … | … |

| Infrequent or frequent dieter vs none | … | … | 1.7 | 0.9–3.2 |

| High level of concern about weight | 2.7 | 1.7–4.4 | 3.0 | 1.4–6.5 |

| Trying to look like persons in the media | 2.2 | 1.4–3.4 | … | … |

| Weight important to father | 1.5 | 0.8–3.0 | … | … |

| Weight important to peers | 1.9 | 0.9–4.1 | … | … |

| Negative weight comments by males | 1.3 | 0.8–2.1 | … | … |

| Negative weight comments by father | … | … | 2.3 | 1.1–4.9 |

| Mother had eating disorder | 1.3 | 0.7–2.5 | 1.3 | 0.4–4.6 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GUTS, Growing Up Today Study; OR, odds ratio; ellipses, not applicable.

SI conversion factor: To convert height to centimeters, multiply by 2.54.

Multivariate ORs and 95% CIs from generalized estimating equation models that included all the covariates with estimates listed in the table. One hundred seventy-four females and 71 males started to binge eat at least weekly during follow-up.

PURGING

Females younger than 14 years whose mother had a history of an eating disorder were 3 times more likely than their peers to start purging, whereas among older adolescent females and all males, a maternal history of an eating disorder was not related to risk of purging (Table 3). Among females of all ages, dieting, weight concerns, and trying to look like females in the media were significant independent predictors of starting to purge. In addition, there was a suggestion among the females that negative comments about weight by males was associated with starting to purge at least weekly. After controlling for dieting, being overweight was not associated with an increased risk of starting to purge (data not shown). Among the males, those who reported that their weight was very important to their peers were significantly more likely than their peers to start purging at least weekly.

Table 3.

Multivariate Analysis for Predictors of Starting to Purge at Least Weekly Between 1996 and 2003 Among Females and Males in GUTSa

| Variable | Females (n=6219)

|

Males (n=4869)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Preadolescent vs adolescent | 0.3 | 0.1–1.1 | 1.1 | 0.5–2.2 |

| Postmenarche vs premenarche | ||||

| Girls <14 y | 2.3 | 1.4–4.1 | … | … |

| Females ≥14 y | 1.5 | 0.5–4.5 | … | … |

| Infrequent dieter vs nondieter | ||||

| Girls <14 y | 4.1 | 2.2–7.8 | … | … |

| Females ≥14 y | 2.8 | 1.9–4.3 | … | … |

| Frequent dieter vs nondieter | ||||

| Girls <14 y | 7.0 | 3.5–14.0 | … | … |

| Females ≥14 y | 3.1 | 1.9–5.2 | … | … |

| Infrequent or frequent dieter vs none | … | … | 2.4 | 0.9–6.1 |

| High level of concern with weight | 2.3 | 1.6–3.2 | 2.5 | 0.7–8.5 |

| Trying to look like persons in the media | 1.5 | 1.1–2.2 | … | … |

| Weight important to father | 1.7 | 0.9–3.0 | … | … |

| Weight important to peers | 1.6 | 0.8–3.1 | 3.4 | 1.0–11.4 |

| Negative weight comments by males | 1.5 | 1.0–2.2 | … | … |

| Negative weight comments by father | 2.1 | 0.6–7.2 | ||

| Mother had an eating disorder | ||||

| <14 y | 2.9 | 1.4–6.1 | 1.5 | 0.4–6.9 |

| ≥14 y | 1.5 | 0.7–2.9 | ||

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GUTS, Growing Up Today Study; OR, odds ratio; ellipses, not applicable.

Multivariate ORs and 95% CIs from generalized estimating equation models that included all the covariates with estimates listed in the table. Two hundred fourteen females and 31 males started to purge at least weekly during follow-up.

BINGE EATING AND PURGING

Only a small percentage of the incident cases of binge eating and purging engaged in both behaviors simultaneously. There were too few males (n=4) who started to engage in both binge eating and purging to conduct a meaningful analysis. Among the females, dieting and concern with weight were risk factors for starting to binge eat and purge at least weekly. Although perceived importance of weight by peers was not significantly related to starting to binge eat or starting to purge among the females, females who reported that it was important to their peers that they be thin were almost 4 times more likely to start binge eating and purging weekly (Table 4).

Table 4.

Multivariate Analysis for Predictors of Starting to Engage in Binge Eating and Purging at Least Weekly Between 1996 and 2003 Among 6182 Females in GUTSa

| Variable | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 1.0 | 0.8–1.2 |

| Menarche | 3.0 | 0.8–11.1 |

| Nondieter | 1 [Reference] | … |

| Infrequent dieter | 2.9 | 1.0–8.8 |

| Frequent dieter | 7.4 | 2.2–25.0 |

| High level of concern about weight | 5.3 | 2.1–13.4 |

| Trying to look like persons in the media | 1.1 | 0.5–2.5 |

| Importance of weight to father | 1.0 | 0.2–4.6 |

| Importance of weight to peers | 3.7 | 1.1–12.4 |

| Negative weight comments by males | 1.2 | 0.5–3.1 |

| Mother had an eating disorder | 1.8 | 0.6–6.0 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GUTS, Growing Up Today Study; OR, odds ratio; ellipsis, not applicable.

Multivariate ORs and 95% CIs from generalized estimating equation model that included all the covariates listed in the table. Thirty-six incident cases started to engage in both binge eating and purging at least weekly.

COMMENT

Among 12 534 adolescents participating in GUTS followed up for 7 years, we observed that 10% of the females and 3% of the males started engaging in bulimic behaviors frequently. Contrary to expectations, we observed that the incidence of purging was higher than the incidence of binge eating among the females. For a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa, an individual must engage in both binge eating and purge behaviors frequently, a combination that few of the frequent binge eaters or purgers in the cohort exhibited. For a diagnosis of binge eating disorder, one must engage in frequent binge eating episodes but exhibit no compensatory behaviors. Our findings suggest that by examining only those 2 combinations of symptoms, a large group of females who purge frequently but do not binge eat frequently are overlooked.24,25

Our finding that a maternal history of an eating disorder is a risk factor for starting to purge among preadolescent and young adolescent females is consistent with findings by Bulik et al,26 who found strong evidence of heritability of anorexia nervosa in a large population-based sample of Swedish twins, and by Reichborn-Kjennerud et al,27 who found strong evidence for a genetic component to binge eating in a sample of 8045 same-sex and opposite-sex Norwegian twins. Neither of these studies found much support for the shared environment being associated with the outcome. However, in the present study, we were unable to determine whether the association with maternal history of an eating disorder was due to genetics or to shared environment. Few studies that have assessed whether subjects with early vs later onset of a disorder vary in terms of the influence of genetics on the risk of becoming eating disordered.28–30 More research is needed to better understand these associations.

Although teasing or negative comments about weight have been proposed as risk factors for becoming eating disordered, the evidence is mixed. Haines et al10 found that the females in Project EAT (Eating Among Teens) who were teased were more likely to become frequent dieters 5 years later, but they did not observe an association between teasing and the development of bulimic behavior. In contrast, among the males, those who had been teased were more likely than their peers to start binge eating, which is consistent with our finding that among the males in GUTS, teasing or negative comments about weight by their fathers was predictive of starting to binge eat. Among the females, teasing by mothers, fathers, and other females was unrelated to the risk of starting to binge or purge weekly, but teasing about weight by males was associated with an increase in the risk of starting to purge weekly. Inasmuch as only teasing by males was predictive among the females in our sample, it is possible that the lack of association by Haines et al10 may reflect grouping of all types of teasing together or the result of not considering purging an outcome.

The role of the media in the development of eating disorders continues to be controversial. Many cross-sectional studies have observed an association between frequency of exposure to the mass media, particularly the print media, and body dissatisfaction and disordered eating,20,31,32 but the results of these studies have been questioned because individuals who are very dissatisfied with their weight or shape might seek out magazines and other forms of media as a result of body dissatisfaction rather than the opposite temporal order of association that is assumed. Stronger evidence comes from a few prospective investigations that have observed an association between exposure to the media and the development of disordered eating among young females.1–3,33,34 In the present study, we observed that trying to look like same-sex persons in the media was a stronger risk factor for females than for males, which suggests that programs to prevent the development of bulimic behaviors should incorporate media literacy in their lesson plans.

Dieting and high level of concern about weight were strong risk factors for all outcomes among females. These findings highlight the need for parents and health care providers (all medical professionals who might deliver care to this age group) to not dismiss dieting and negative comments about body weight as harmless rites of passage among young females; rather, they should be thought of as potential warning signs to be investigated further. Although dieting was a risk factor for all of the outcomes, there were notable differences in predictors of starting to binge eat, starting to purge, and starting to binge eat and purge. For example, among the females, peer influences had a much stronger association with starting to binge eat and purge weekly than with starting to engage in only 1 bulimic behavior. Moreover, risk factors differed by age and sex. Purging frequently, regardless of whether someone binge eats, is a cause for concern and warrants treatment.

A limitation of our study is that it does not represent a random sample of all US adolescents and young adults. The participants were children of nurses and the sample was more than 90% white; thus, it is unlikely that there were children of low socioeconomic status in the sample. Therefore, it is unclear whether the results of the study are generalizable to nonwhite ethnic groups or to economically disadvantaged populations. However, there are many strengths to the current study that offset this limitation. The study is the largest study of disordered eating with repeated assessments of a wide range of exposures and a long follow-up. In addition, the study was sufficiently large to assess risk factors separately by age group (among the females) and sex, which proved important because risk factors varied by age group among the females.

Our results suggest that prevention of disordered eating and eating disorders may need to be age- and sex-specific. Efforts aimed at females should contain media literacy and other approaches to make young persons less susceptible to the media images they see. In addition, programs for females should focus more on becoming more resilient to teasing from males, whereas programs for males should focus on approaches to becoming more resilient to negative comments about weight by fathers. Although males are less likely than females to develop disordered eating, parents and clinicians should be aware that negative comments about weight can have serious consequences such as making young males more likely to start binge eating frequently. It is, therefore, of utmost importance that parents, teachers, and clinicians promote maintaining a healthy weight without overemphasizing the importance of weight or stigmatizing overweight youth.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: The analysis was supported by research grants DK-46834 and DK-59570 from the National Institutes of Health and support from the Kellogg Company and the Boston Obesity Nutrition Research Center (DK-46200).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Additional Contributions: S. Bryn Austin, ScD, and Ruth Streigel-Moore, PhD, provided comments on preliminary analyses.

Author Contributions: Dr Field had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Field, Camargo, and Laird. Acquisition of data: Field and Camargo. Analysis and interpretation of data: Field, Javaras, Aneja, Kitos, and Taylor. Drafting of the manuscript: Field, Kitos, and Taylor. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Field, Javaras, Aneja, Kitos, Camargo, Taylor, and Laird. Statistical analysis: Field, Javaras, Aneja, Taylor, and Laird. Obtained funding: Field. Administrative, technical, and material support: Kitos. Study supervision: Field.

References

- 1.Field AE, Camargo CA, Jr, Taylor CB, Berkey CS, Colditz GA. Relation of peer and media influences to the development of purging behaviors among preadolescent and adolescent girls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(11):1184–1189. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.11.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Field AE, Camargo CA, Jr, Taylor CB, Berkey CS, Roberts SB, Colditz GA. Peer, parent, and media influences on the development of weight concerns and frequent dieting among preadolescent and adolescent girls and boys. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):54–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Revised. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobi C, Hayward C, de Zwaan M, Kraemer HC, Agras WS. Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychol Bull. 2004;130(1):19–65. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Field AE, Austin SB, Taylor CB, et al. Relation between dieting and weight change among preadolescents and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;112(4):900–906. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patton GC, Selzer R, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Wolfe R. Onset of adolescent eating disorders: population-based cohort study over 3 years. BMJ. 1999;318(7186):765–768. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7186.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKnight Investigators. Risk factors for the onset of eating disorders in adolescent girls: results of the McKnight Longitudinal Risk Factor Study [published correction appears in Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(5):1024] Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(2):248–254. doi: 10.1176/ajp.160.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agras WS, Bryson S, Hammer LD, Kraemer HC. Childhood risk factors for thin body preoccupation and social pressure to be thin. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(2):171–178. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e31802bd997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardner RM, Stark K, Freedman J, Jackson NA. Predictors of eating disorder scores in children ages 6 through 14: a longitudinal study. J Psychosom Res. 2000;49(3):199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(00)00172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haines J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Eisenberg ME, Hannan PJ. Weight and disordered eating behaviors in adolescents: longitudinal findings from Project EAT (Eating Among Teens) Pediatrics. 2006;117(2):e209–e215. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Killen JD, Taylor CB, Hayward C, et al. Weight concerns influence the development of eating disorders: a 4-year prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(5):936–940. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Killen JD, Taylor CB, Hayward C, et al. Pursuit of thinness and onset of eating disorder symptoms in a community sample of adolescent girls: a three-year prospective analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 1994;16(3):227–238. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199411)16:3<227::aid-eat2260160303>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kotler L, Kasen S, Brook JS. Psychiatric disorders associated with risk for the development disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70(5):1119–1128. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.5.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA, Finemore J. The role of puberty, media and popularity with peers on strategies to increase weight, decrease weight and increase muscle tone among adolescent boys and girls. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52 (3):145–153. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison K, Hefner V. Media exposure, current and future body ideals, and disordered eating among preadolescent girls: a longitudinal panel study. J Youth Adolesc. 2006;35(2):153–163. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hudson JI, Lalonde JK, Berry JM, et al. Binge-eating disorder as a distinct familial phenotype in obese individuals. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(3):313–319. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Solomon CG, Willett WC, Carey VJ, et al. A prospective study of pregravid determinants of gestational diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 1997;278(13):1078–1083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320 (7244):1240–1243. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shisslak CM, Renger R, Sharpe T, et al. Development and evaluation of the McKnight Risk Factor Survey for assessing potential risk and protective factors for disordered eating in preadolescent and adolescent girls. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25 (2):195–214. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199903)25:2<195::aid-eat9>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCabe MP, Ricciardelli LA. Sociocultural influences on body image and body changes among adolescent boys and girls. J Soc Psychol. 2003;143(1):5–26. doi: 10.1080/00224540309598428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohane GH, Pope HG., Jr Body image in boys: a review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 2001;29(4):373–379. doi: 10.1002/eat.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kann L, Warren CW, Harris WA, et al. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 1995. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 1996;45(4):1–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Field AE, Taylor CB, Celio A, Colditz GA. Comparison of self-report to interview assessment of bulimic behaviors among preadolescent and adolescent girls and boys. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;35(1):86–92. doi: 10.1002/eat.10220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keel PK, Haedt A, Edler C. Purging disorder: an ominous variant of bulimia nervosa? Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38(3):191–199. doi: 10.1002/eat.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wade TD, Bergin JL, Tiggemann M, Bulik CM, Fairburn CG. Prevalence and long-term course of lifetime eating disorders in an adult Australian twin cohort. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2006;40(2):121–128. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2006.01758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Tozzi F, Furberg H, Lichetenstein P, Pederson NL. Prevalence, heritability, and prospective risk factors for anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(3):305–312. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Bulik CM, Tambs K, Harris JR. Genetic and environmental influences on binge eating in the absence of compensatory behaviors: a population-based twin study. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;36(3):307–314. doi: 10.1002/eat.20047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reba L, Thornton L, Tozzi F, et al. Relationships between features associated with vomiting in purging-type eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38(4):287–294. doi: 10.1002/eat.20189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klump KL, McGue M, Iacono WG. Differential heritability of eating attitudes and behaviors in prepubertal versus pubertal twins. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;33(3):287–292. doi: 10.1002/eat.10151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klump KL, Perkins PS, Alexandra Burt S, McGue M, Iacono WG. Puberty moderates genetic influences on disordered eating. Psychol Med. 2007;37(5):627–634. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Field AE, Cheung L, Wolf AM, Herzog DB, Gortmaker SL, Colditz GA. Exposure to the mass media and weight concerns among girls. [Accessed May 1, 1999];Pediatrics. 1999 103(3):E36. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.3.e36. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/103/3/e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Utter J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Story M. Reading magazine articles about dieting and associated weight control behaviors among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2003;32(1):78–82. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00455-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martínez-González MA, Gual P, Lahortiga F, Alonso Y, de Irala-Estévez J, Cervera S. Parental factors, mass media influences, and the onset of eating disorders in a prospective population-based cohort. Pediatrics. 2003;111(2):315–320. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.2.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van den Berg P, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ, Haines J. Is dieting advice from magazines helpful or harmful? five-year associations with weight-control behaviors and psychological outcomes in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):e30–e37. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]