Abstract

A feathered specimen of a new species of Eocypselus from the Early Eocene Green River Formation of Wyoming provides insight into the wing morphology and ecology in an early part of the lineage leading to extant swifts and hummingbirds. Combined phylogenetic analysis of morphological and molecular data supports placement of Eocypselus outside the crown radiation of Apodiformes. The new specimen is the first described fossil of Pan-Apodiformes from the pre-Pleistocene of North America and the only reported stem taxon with informative feather preservation. Wing morphology of Eocypselus rowei sp. nov. is intermediate between the short wings of hummingbirds and the hyper-elongated wings of extant swifts, and shows neither modifications for the continuous gliding used by swifts nor modifications for the hovering flight style used by hummingbirds. Elongate hindlimb elements, particularly the pedal phalanges, also support stronger perching capabilities than are present in Apodiformes. The new species is the smallest bird yet described from the Green River Formation, and supports the hypothesis that a decrease in body size preceded flight specializations in Pan-Apodiformes. The specimen also provides the first instance of melanosome morphology preserved in association with skeletal remains from the Green River Formation.

Keywords: Aves, Eocene, feathers, phylogeny, Apodiformes

1. Introduction

An unparalleled fossil assemblage from the Early Eocene Fossil Butte Member of the Green River Formation has shed light on the taxonomic composition and ecological diversity of one of the earliest known Caenozoic avifaunas. Fossil feathers, in particular, have revealed details of wing shape in Eocene birds that cannot be inferred from skeletal specimens alone, and have been recovered from Fossil Butte Member deposits both as isolated specimens and associated with semi-articulated skeletons [1–5]. Feathers occur in the Fossil Butte Member in various states ranging from poorly preserved carbonized traces to finely preserved specimens with identifiable rachises and barbs. Formerly, detailed feather preservation in Green River birds was attributed to fossilized feather-degrading bacteria and associated glycocalyces [6]. More recently, apparent microbes associated with feather preservation at other localities have been reinterpreted as melanosomes [7]. Melanosomes have thus far been described only from one isolated feather from an unidentified Green River bird [8]. Here, we report a representative of Pan-Apodiformes with well-preserved plumage and intact melanosomes.

Pan-Apodiformes comprises the tree swifts (Hemiprocnidae), true swifts (Apodidae) and hummingbirds (Trochilidae), along with their extinct relatives. Despite their small average body size, they have a relatively extensive Palaeogene fossil record in some regions. A plethora of ‘swift-like’ fossil birds are known from Eocene–Oligocene deposits throughout Europe [9–16]. Although superficially swift-like in skeletal morphology, only a few of these extinct species are closely related to extant Apodidae. Several of these taxa are members of the hummingbird stem lineage [17], whereas others fall outside the crown clade Apodiformes [16]. Surprisingly, no Pan-Apodiformes have been formally described from contemporary deposits of North America, nor indeed from any pre-Pleistocene North American deposits. This apparent disparity between the European and North American Palaeogene avifaunas may be deceptive, given that several specimens of swift-like birds from the Green River Formation reside in private collections [1,2] and also because such small taxa may potentially suffer from collecting biases.

Extant Apodiformes exhibit some of the most unique flight characteristics among birds, in terms of overall wing shape, feather structure and flight style. Hummingbirds possess a short blade-like wing and use a unique hovering flight style that generates lift on both the upstroke and downstroke [18]. Swifts, by contrast, have greatly elongated wings that allow them to excel at metabolically efficient gliding and also reach the fastest speeds measured for birds in level flight [19]. Both swifts and hummingbirds exhibit a variety of ornamental tail shapes and colour patterns [19–22]. Given the disparity in wing shape observed within extant swifts and hummingbirds, fossil relatives of extant swifts and hummingbirds are key to informing the ancestral wing shape and flight style in Pan-Apodiformes. Proportions and discrete characters of the wing skeleton have provided insights into the flight style of extinct Pan-Apodiformes [16,23,24], but predicting feather length is difficult from skeletal remains alone. Thus, feathered specimens are particularly important in reconstructing the early evolution of these specialized birds.

2. Systematic palaeontology

Strisores Baird 1858

Cypselomorphae Huxley 1867

Pan-Apodiformes Mayr 2010

Eocypselidae Harrison 1984

Eocypselus Harrison 1984

Eocypselus rowei sp. nov.

(a). Holotype

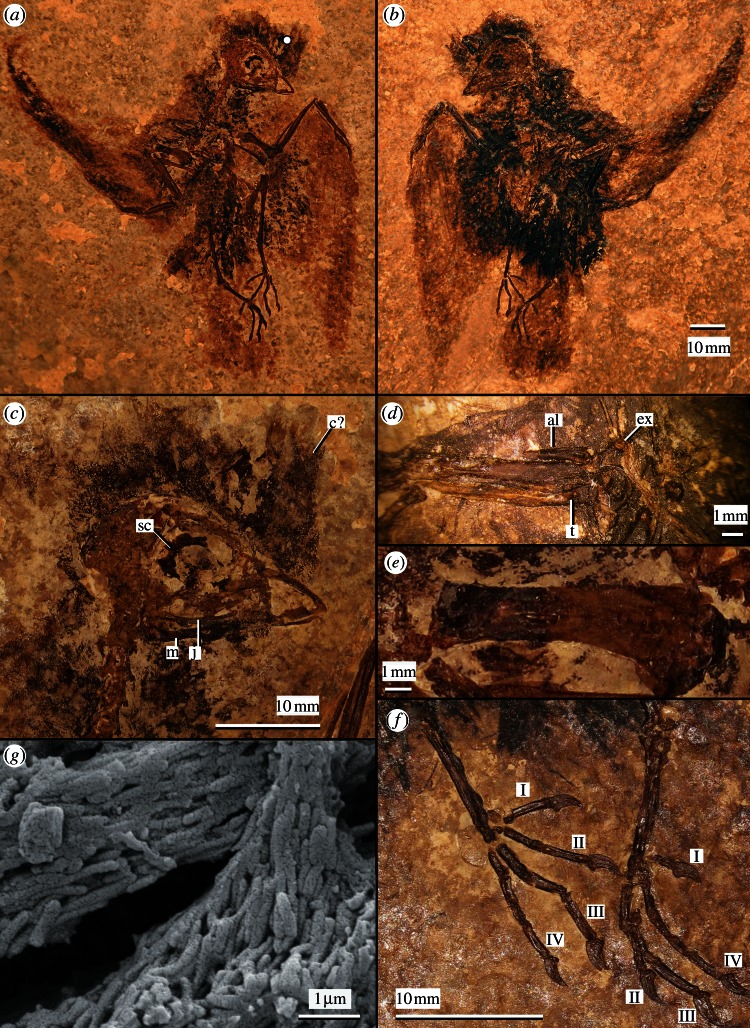

Wyoming Dinosaur Center (WDC, Thermopolis, WY, USA) CGR-109, complete skeleton with intact feathering preserved as slab and counterslab (figure 1). Measurements are presented in table 1.

Figure 1.

Holotype specimen of Eocypselus rowei (WDC-CGR-109): (a) main slab and (b) counterslab, with close-ups of (c) skull, (d) right carpometacarpus in ventral view, (e) right humerus in caudal view and (f) the left and right pes. al, alular phalanx; c?, feathers of possible head crest; ex, processus extensorius; j, jugal; m, mandible; sc, sclerotic ring; t, tubercle on ventral face on metacarpal III. Pedal digits are labelled I, II, III and IV. The white dot in (a) demarcates the location of sample for scanning electron microscopy depicted in (g), showing abundant three-dimensionally preserved eumelanosomes. Surface crackle in the image is an artefact of the original gold coating.

Table 1.

Measurements from WDC-CGR-109.

| element | dimension | measurement (left/right; mm) |

|---|---|---|

| skull | length | 24.1 |

| scapula | length | —/15.0 |

| humerus | length | —/12.1 |

| midshaft width | —/2.3 | |

| radius | length | —/16.5 |

| carpometacarpus | length | 10.8/10.8 |

| alular phalanx | length | 2.9/3.0 |

| phalanx II-1 | length | 5.4/5.5 |

| phalanx II-2 | length | 5.2/5.3 |

| phalanx III-1 | length | —/3.0 |

| primary feather | tip of phalanx II-2 to tip of feather | 55.5 |

| femur | length | —/∼11 |

| tibiotarsus | length | 20.0/20.2 |

| tarsometatarsus | length | 10.0/10.0 |

(b). Etymology

The species name honours John W. Rowe, a generous and knowledgeable supporter of evolutionary research and educational outreach at The Field Museum in Chicago, Illinois, where he is currently serving as chairman of the board.

(c). Locality and horizon

Locality B [25], also known as Lewis Ranch Site 2 or Smith Hollow Quarry, of the Fossil Butte Member of the Green River Formation of Lincoln County, Wyoming, USA. Deposits at this locality are from a mid-lake setting (F-1 facies of Grande & Buchheim [25]) and have previously yielded partial skeletons of the stem frigatebird Limnofregata azygosternon [4] and the stem roller Primobucco mcgrewi [26]. Radiometric 40Ar/39Ar dating of an overlying tuff deposit indicates an age of approximately 51.66 ± 0.09 Ma for the fossil horizon [27].

(d). Diagnosis

Eocypselus rowei differs from Eocypselus vincenti by (i) the stouter humerus (midshaft width equals approx. 20% total length for E. rowei versus 13% for the E. vincenti holotype), (ii) the presence of a rounded tubercle that projects ventrally from the body of metacarpal III near the contact with the trochlea carpalis and (iii) a proportionally shorter tarsometatarsus (tarsometatarsus length equals 50% of tibiotarsus length versus 54% for E. vincenti). The second character is not present in E. vincenti (fig. 6f of [16]) and other Pan-Apodiformes, and is considered an apomorphy of E. rowei. In comparing proportions, we note that the specimen is not badly crushed. Rather, it has been damaged by the splitting of the slab, so that several long bones are broken into two pieces exposing the internal surfaces. An expanded differential diagnosis is included in the electronic supplementary material.

(e). Comment

Pan-Apodiformes is defined here as the clade uniting all taxa more closely related to Apodiformes than to any other extant taxon of Strisores (Aegothelidae, Nyctibiidae, Caprimulgidae, Steatornithidae and Podargidae).

(f). Scanning electron microscope methods

Samples from WDC-CGR-109 were initially coated with gold, but had to be recoated with 15 nm of gold/palladium mixture to prevent charging. Samples were imaged with a Zeiss Supra 40 VP field emission scanning electron microscope (located at University of Texas at Austin, Institute for Cellular and Molecular Biology) using 5 kV accelerating voltage and 15 mm working distance.

(g). Phylogenetic analysis

We expanded a recently published combined phylogenetic matrix [28] (see also [16,17,29–32]) by adding 17 characters and 14 taxa. Taxonomic sampling includes eight extant species and seven fossil species of Pan-Apodiformes. In order to polarize character states, we also included 10 representatives of Strisores, the larger clade uniting the paraphyletic ‘Caprimulgiformes’ [29] and Pan-Apodiformes. Because the placement of Strisores within the context of higher avian phylogeny remains controversial, we rooted trees to the palaeognath Crypturellus undulatus. Taxa were sampled at the species level to facilitate inclusion of molecular data. Molecular data were obtained from GenBank for the genes cytochrome b, RAG-1, myoglobin exon 2 and c-myc exon 3, and aligned using ClustalX [33]. A nexus file containing the matrix, along with character descriptions, GenBank accession numbers for molecular sequences and a list of specimens examined, is presented in the electronic supplementary material.

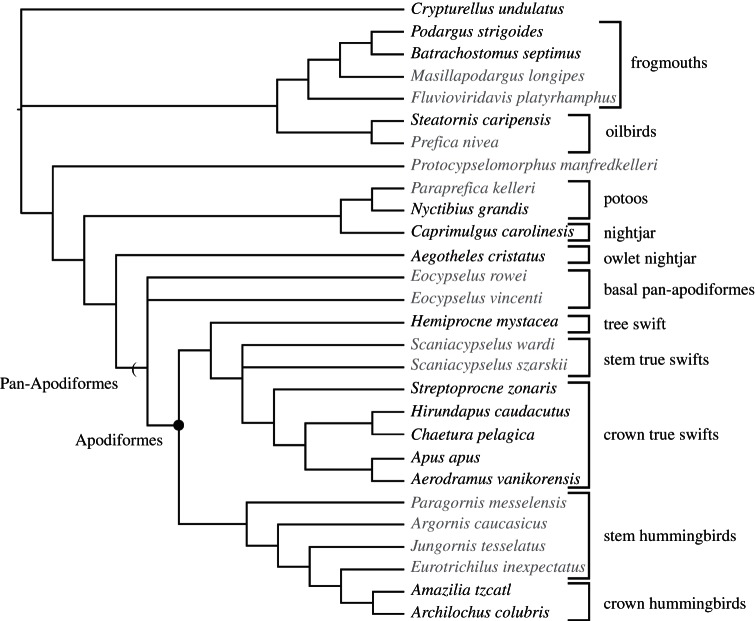

Two analyses, the first one using the combined dataset and the second using only the morphological dataset, were conducted using PAUP*4.0b10 [34], with a branch and bound search strategy. All characters were equally weighted, multistate codings were used only to represent polymorphism and branches with a minimum length of zero were collapsed. A single most parsimonious tree (tree length, TL = 3744 steps) was recovered in the combined analysis (figure 2). Results of the analysis using only morphological data also yielded a single most parsimonious tree (TL = 235) that is identical to the tree from the combined analysis with the exception that the branch uniting the extant swifts Aerodramus vanikorensis and Apus apus collapsed.

Figure 2.

Most parsimonious tree from combined analysis (TL = 3744 steps, RC = 0.329, RI = 0.484). The topology of the most parsimonious tree from the morphological analysis (TL = 235 steps, RC = 0.436, RI = 0.794) is identical with the exception that the branch uniting Apus and Aerodramus is collapsed. Extinct taxa are indicated by grey font.

Our results agree with one previous hypothesis (fig. 8 of [16]) in placing Eocypselus basal to the swift–hummingbird split. Eocypselus is supported as a member of Pan-Apodiformes by two unambiguous synapomorphies: an abbreviated humerus (character 54: state 1, ratio of length to midshaft width less than 10.0) and an ossified arcus extensorius of the tarsometatarsus (92 : 1; see [16]). Monophyly of crown Apodiformes to the exclusion of Eocypselus is supported by eight derived characters (see the electronic supplementary material). Another previous study recovered Eocypselus within the crown clade Apodiformes [35] (see comments on scoring issues in [36]), but we find no support for this hypothesis, which is 12 steps less parsimonious using our dataset.

Eocypselus vincenti and E. rowei did not form a clade in our results. We consider this result likely to be related to the incomplete preservation of bone surfaces on the E. rowei holotype, which precludes scoring of characters that may potentially unite these fossil taxa (see the electronic supplementary material).

A key finding of the new analysis is that the Eocene Scaniacypselus wardi and Scaniacypselus szarskii are supported as members of the stem lineage leading to Apodidae, more closely related to extant true swifts than to tree swifts. Scaniacypselus has previously proved difficult to place, because this taxon retains some primitive character states supporting a stem placement [17], but also other features that have been interpreted as potentially supporting placement within crown Apodidae [9,12]. One previous phylogenetic analysis of a smaller character set with more limited taxonomic sampling yielded S. wardi in a position basal to the tree swift–true swift (Apodidae–Hemiprocnidae) split [35], whereas another recovered composite terminals coded for Scaniacypselus, Apodinae and Cypseloidini [37] in a polytomy.

Species-level codings and expanded character sampling help resolve the placement of Scaniacypselus, which is supported as a basal member of Pan-Apodidae by four synapomorphies: the great abbreviation of the humerus (54 : 2, ratio of length to midshaft width less than 5.0), strong projection of the processus supracondylaris dorsalis (62 : 1), proximal displacement of this process (63 : 1) and elongation of the carpometacarpus (72 : 2, carpometacarpus exceeding humerus in length). Scaniacypselus is excluded from crown Apodidae by retention of plesiomorphic character states, including the presence of a shallow fossa m. brachialis of the humerus as opposed to the derived absence of this fossa (61 : 1), a blunt olecranon as opposed to the narrow and elongate olecranon in crown swifts (70 : 0) and proximal phalanges of the fourth pedal digit that are equal in length to the distal phalanges, as opposed to strongly abbreviated (100 : 0). With the precise phylogenetic position of S. wardi recovered, this taxon provides a calibration point of approximately 51 Ma for the divergence between Apodidae and Hemiprocnidae.

Relationships within Apodidae have not received much prior study. Our results contribute to resolving the phylogeny of swifts, indicating a basal divergence between Cypseloidini (represented by Streptoprocne) and other extant Apodidae. This result is congruent with a phylogeny based on the ZENK gene [38]. A clade including all crown Apodidae to the exclusion of Cypseloidini is ambiguously supported by the derived attachment of m. tensor propatagialis pars brevis at the proximally displaced processus supracondylaris dorsalis (64 : 2; see [39]), and unambiguously supported by the derived presence of a proximally directed flange extending proximally from the base of the plantar flange of trochlea metatarsi II (97 : 2) and diastataxic feathering (106 : 1). We find no support for a previous morphology-based hypothesis that Streptoprocne represents a more basal divergence, sister to Hemiprocnidae + all other Apodidae [40].

Our results differ from previous molecular studies [38] and agree with morphology-based hypotheses [40] in supporting monophyly of the Chaeturini (represented by Chaetura and Hirundapus). This clade is supported by the presence of a bony canal on the plantar surface of the base of trochlea metatarsi II (98 : 1) and the presence of needle-like rectrices (117 : 1). A clade uniting Aerodramus (Collocaliini) and Apus (Apodini) was supported in our combined analysis, in agreement with Chubb [38], though we identified no morphological synapomorphies of this clade, which collapses in our morphology-only analysis. The grouping of Collocaliini and Apodini to the exclusion of Chaeturini was also supported by a multi-locus molecular analysis [41], though that study did not include any representatives of Cypseloidini.

Relationships within Trochilidae are congruent with previous hypotheses [16,17,42], but more fully resolved, with the placement of Argornis closer to the crown clade than Parargornis supported by the elongation of the carpometacarpus (72 : 2).

3. Skeletal anatomy and feathering

Eocypselus rowei was a very small bird, with a total body size slightly smaller than that of the extant Chaetura pelagicus (chimney swift). Although the holotype is essentially complete, many bones were split along with the slab, so that surface details such as muscle insertions are not observable. It is evident that the impressions of limb bones have been retouched with paint in a few obvious areas. However, microscopic details of preserved feathers indicate these structures are genuine.

A complete but poorly preserved skull preserves a short, rounded beak. Proportions are similar to those in extant swifts, but notably the tip does not show evidence of downturning. The internarial bar is narrow, and the nares extend nearly to the tip of the beak. The mandible is very slender. Although the sclerotic ring is incomplete, it does not appear to show any specializations such as enlargement or tubular morphology. As indicated by the articulated vertebral column, the foramen magnum appears to have faced ventrally. The prominentia cerebellaris appears to have projected caudally far past the margin of the foramen magnum.

Although the sternum is not well preserved, it appears that the sulci for the coracoids are oriented at an angle of less than 45°, so that the coracoids are strongly laterally directed in articulation. It is also clear that the caudal border of the sternum was wide and flat. No evidence of incisurae or fenestrae is visible, but because of poor preservation their presence cannot be ruled out with certainty. In both coracoids, the omal ends are mostly intact, and the sternal portions are preserved as impressions. The processus acrocoracoideus is hooked as in other Pan-Apodiformes and in Aegothelidae. Although damaged on its medial edge, the cotyla scapularis of the coracoid is clearly cup-shaped as in extant Apodiformes. The scapular blade is straight over the proximal two-thirds of its length, but prominently deflected at its distal end. The furcula is broken into three segments with slight displacement. A portion from near the symphysis is quite robust in cross-section and bears a small apophysis furculae. Two sections from the omal ends of the furcula show a more flattened cross-section.

The humerus is strongly abbreviated. The crista bicipitalis is proximodistally short and rounded. Details of the crista deltopectoralis are not preserved. A small processus supracondylaris dorsalis (origin of m. extensor radialis metacarpalis) is present on the craniodorsal margin of the bone and is distally placed as in E. vincenti. The radius lacks the prominent distal tubercle present in extant Apodiformes [17]. The ulna exhibits a blunt olecranon and a prominent tuberculum carpale. The carpometacarpus bears a strongly projected processus extensorius. A rounded tubercle projects ventrally from the body of metacarpal III near the trochlea carpalis and is considered an autapomorphy of E. rowei. Metacarpal III is straight and thin, and the spatium intermetacarpale is narrow. As in most members of Strisores, phalanx II-1 bears two depressions divided by a ridge. A short processus internus indicis is present, but is much less strongly projected than in crown Apodiformes [16,29]. Phalanx II-2 lacks the expanded distal tip seen in crown Apodiformes.

The pelvis is wide, and the foramen obturatum is incompletely closed. The pubis is long and slender. A wide space separates the pubis and ischium distally, as in crown Apodiformes and Aegothelidae. The distal portion of the pubis is curved and contacts the ischium at a high angle, though the tip is free.

The hindlimbs are proportionally long and slender compared with those of extant Apodiformes. The tarsometatarsus is preserved in articulation with the short metatarsal I. Trochlea metatarsi II is retracted proximal to the level of trochlea metatarsi III. A deep sulcus is present between trochleae metatarsorum III and IV. The pedal digits are fairly long, with both digit III and digit IV exceeding the tarsometatarsus in length. Digit II is substantially shorter. The proximal two phalanges of digit IV are each about half the size of the penultimate phalanx, rather than being highly reduced as in Apodidae. The unguals are short, modestly curved and have moderately developed flexor tubercles.

Individual feathers can be discerned within the darkened halo surrounding the skull. If the feathers preserved near the base of the beak are not displaced, then a feathered head crest may have been present. Such crests occur in some extant Apodiformes, including tree swifts (Hemiprocnidae) and some hummingbirds (e.g. Orthorhyncus cristatus) [19,21]. Feather preservation along the wing is of high quality, with darkened rachises and individual barbs visible. The primaries are elongate, and the outermost feathers are longer than the entire wing skeleton, accounting for more than 50 per cent of total wing length. As preserved, the outer primaries are much longer than the inner primaries (visible on the left side), indicating a relatively high aspect ratio. A small feather near the leading edge of the left wing is tentatively identified as a covert. On the right side, the rounded distal end of the outermost rectrix appears to be intact, suggesting the very short and squared tail shape reflects the true morphology. One previously reported specimen of E. vincenti preserves feather impressions, but these are too incomplete to provide information on wing or tail shape [15,43].

Eocypselus rowei provides insights into the variability of melanosome preservation in Green River feathers. Three-dimensionally preserved melanosomes from the dorsal head feathers of E. rowei are interpreted as well-defined, densely packed and dominantly rod-like eumelanosomes (figure 1g). Such morphologies are most commonly associated with black, glossy black and some forms of iridescent colours in birds [44]. Additional sampling along the wing feathering revealed melanosome morphologies represented primarily as voids rather than as three-dimensional forms. Although melanosome preservation has been reported in fossil feathers from other lacustrine and near-shore depositional environments [45–49], only one account of melanosomes in Green River feathers has been reported. Wogelius et al. [8] sampled three isolated Green River feathers and an isolated wing with feathers. All had regions containing high amounts of copper, a proposed biomarker of melanin [8]. However, only in one of the isolated feathers were three-dimensionally preserved melanosomes, described as rod-like eumelanosomes [8], discernible. In the other three specimens, preserved evidence of melanosome morphology was not reported, despite macrostructural feather preservation.

4. Discussion

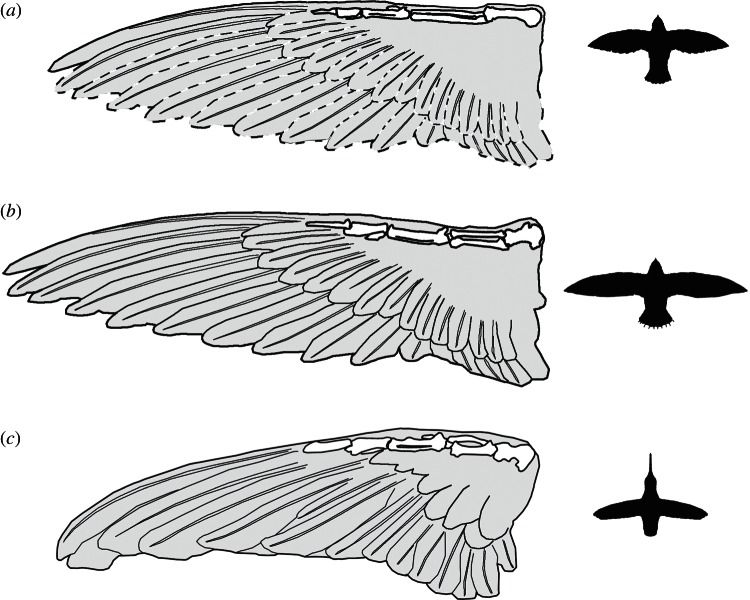

Despite sharing distinctive features of the wing skeleton, such as a remarkably stout humerus and elongate carpometacarpus and phalanges, swifts and hummingbirds have markedly different wing shapes. Shortening of the humerus results in a shift in muscle attachments towards the shoulder joint, which in turn reduces moment of inertia [23,50]. Elongation of the primary feathers has been hypothesized to compensate for shortening of the proximal wing skeleton in Apodiformes [23]. In swifts, abbreviation of the proximal wing bones is indeed accompanied by elongation of the distal wing bones as well as the primaries, resulting in overall elongation of the wing (figure 3) and optimization for fast flap-gliding and gliding flight. Hummingbirds also possess a strongly abbreviated humerus and elongated primaries, but have much shorter wings relative to overall body size, resulting in the higher wing loading values used in hovering flight [51,52].

Figure 3.

Comparison of wing structure in (a) Eocypselus rowei (WDC-CGR-109), (b) an extant swift (Apodidae: Hirundapus caudacutus: University of Washington Burke Museum, UWBM 47230) and (c) an extant hummingbird (Trochilidae: Archilochus colubris: UWBM 49825), with overall body outlines at right. Skeletal elements (right side) and spread wings (left side) from the same specimen were outlined and traced, with wings mirrored to create images for extant taxa. For the fossil taxon wing length was reconstructed from the leading primary, and dotted lines indicate the uncertain breadth of the wing. For comparison, wings were scaled to the same skeletal wing length and body outlines to the same head-to-tail length (excluding the long beak of the hummingbird).

Because the disparate wing shapes of extant swifts and hummingbirds are only truly appreciable when feathering is taken into account, it is difficult to infer the ancestral wing morphology for Apodiformes based solely on data from extant taxa and fossils that preserve only skeletal material. While the brachial index (humerus : ulna ratio) [53] of Eocypselus falls within the range of extant swifts (table 2), the overall wing length in the fossil taxon is much shorter. Likewise, despite the fact that the carpometacarpus and phalanges of E. rowei are shorter than those of hummingbirds, the primary feathers are proportionally longer.

Table 2.

Comparative ratios of wing bones for Pan-Apodiformes. Ratios for fossil hummingbirds, extant Trochilidae and extant Apodidae from [24], ranges for Eocypselus vincenti from [16]. Ulna length of Eocypselus rowei was estimated from the length of the intact radius.

| taxon | humerus : ulna | CMC : humerus | phalanx II-1 : CMC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eocypselus rowei | 0.73 | 0.89 | 0.50 |

| Eocypselus vincenti | 0.72–0.76 | 0.86–0.90 | — |

| Hemiprocne mystacea | 0.84 | 0.93 | 0.67 |

| Scaniacypselus wardi | 0.66 | 1.35 | — |

| extant Apodidae | 0.86–0.94 | 1.22–1.41 | 0.76–0.85 |

| Parargornis messelensis | 0.64 | 0.93 | — |

| Argornis caucasicus | 0.65 | 1.11 | — |

| Jungornis tesselatus | 0.62 | — | — |

| Eurotrochilus inexpectus | 0.74–0.79 | — | — |

| Eurotrochilus noniewiczi | 0.97 | 1.09 | 0.60 |

| Eurotrochilus sp. | 0.74 | 1.15 | 0.55–0.60 |

| extant Trochilidae | 0.64–0.72 | 1.23–1.45 | 0.56–0.65 |

Scaniacypselus szarskii provides the best data on feathering from an early swift [12]. In this taxon, the primaries greatly exceed the combined length of the wing bones and appear to have accounted for about two-thirds of the overall wing length. However, because this species is closely related to Apodidae, it provides little insight into the ancestral wing morphology of Apodiformes. A single specimen of the stem hummingbird Parargornis messelensis with fine feather preservation reveals a different morphology—a short, rounded wing—in a stem member of the hummingbird lineage [13].

Eocypselus rowei provides the first direct evidence of overall wing shape in a stem lineage representative of Pan-Apodiformes. This specimen shows a wing shape intermediate between that of extant swifts and hummingbirds. The outermost primary (55 mm) slightly exceeds the combined length of the wing bones. In the similarly sized stem hummingbird P. messelensis, this primary is less than half as long (approx. 25 mm), whereas the outermost primary is much longer (approx. 74 mm) in the slightly smaller stem true swift S. szarskii. The moderately elongated wing feathering and the phylogenetic position of Eocypselus outside the crown clade Apodiformes together support the inference that the shortened wings of hummingbirds and the elongated wings of swifts were each derived from a less specialized ancestral wing shape.

Extant swifts have very short legs and rarely perch during their foraging intervals. Thus, it is noteworthy that the elongate hindlimbs and toes of Eocypselus appear suited to perching [16]. Because the stem hummingbird Parargornis also possessed elongate legs, it is likely that the shortened hindlimbs of extant swifts arose after the divergence between swifts and hummingbirds, perhaps in order to conserve mass in support of a highly aerial lifestyle [13].

Eocypselus rowei falls within the lower end of the size spectrum for extant swifts. This species represents the smallest reported avian species from the diverse Green River avifauna. With the exception of the elongated carpometacarpus, all overlapping skeletal elements are shorter than those of the tiny birds Eozygodactylus americanus [54] and Neanis kistneri [55]. Consistent with a mass reduction strategy, extant Apodiformes are very small birds and include the smallest known avian species Mellisuga helenae (bee hummingbird). Most fossil and extant representatives of Strisores are relatively large birds, though the Aegothelidae (owlet nightjars) fall within the size range of large swifts. Given the small size of E. rowei and support for Aegothelidae as the extant sister clade of Apodiformes [17], a shift to small body size can reliably be inferred to have occurred well prior to the swift–hummingbird split.

Eocypselus rowei offers a glimpse into the early evolution of one of the most diverse and ecologically important clades of birds. Similar stem Pan-Apodiformes survived alongside more derived stem swifts for much of the Eocene, but appear to have died out by near the Eocene–Oligocene boundary in Europe [56]. Owing to the very sparse North America record and complete lack of sampling in South America, the patterns of replacement among Pan-Apodiformes in the New World remain shrouded in uncertainty.

Acknowledgements

We thank Burkhardt Pohl for making the specimen available for study, Connie Van Beek for assistance with preparation and William Simpson for fossil collection assistance. Ron Eng, Rob Faucett, Helen James, James Dean, Mark Florence, Gerald Mayr, Eberhard Frey, Becky Desjardens, Christian Sidor, Brian O'Shea and Dave Willard provided access to fossils and extant skeletal material. This project was supported by National Science Foundation grants EAR nos 0719758, 0719943 and 0938199.

References

- 1.Grande L. 1984. Paleontology of the Green River Formation, with a review of the fish fauna. Bull. Geol. Survey Wyoming 63, 1–333 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grande L. 2013. The lost world of fossil lake: snapshots from deep time. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olson SL. 1977. A lower Eocene frigatebird from the Green River Formation of Wyoming (Pelecaniformes, Fregatidae). Sm. C. Paleob. 35, 1–33 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olson SL, Matsuoka H. 2005. New specimens of the early Eocene frigatebird Limnofregata (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae), with the description of a new species. Zootaxa 1046, 1–15 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ksepka DT, Clarke JA. 2010. New fossil mousebird (Aves: Coliiformes) with feather preservation provides insight into the ecological diversity of an Eocene North American avifauna. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 160, 685–706 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00626.x (doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00626.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis PG, Briggs DEG. 1995. Fossilization of feathers. Geology 23, 783–786 (doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1995)023<0783:FOF>2.3.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vinther J, Briggs DEG, Prum RO, Saranathan V. 2008. The colour of fossil feathers. Biol. Lett. 4, 522–525 10.1098/rsbl.2008.0302 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0302) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wogelius RA, et al. 2011. Trace metals as biomarkers for eumelanin pigment in the fossil record. Science 333, 1622–1626 10.1126/science.1205748 (doi:10.1126/science.1205748) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison CJO. 1984. A revision of the fossil swifts (Vertebrata, Aves, suborder Apodi), with descriptions of three new genera and two new species. Mededelingen van de Werkgroep voor Tertiaire en Kwartaire Geologie 21, 157–177 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karhu A. 1988. Novoye semeystvo strizheobraznykh iz paleogena Yevropy. Paleontol. Zh. 3, 78–88 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peters DS. 1998. Erstnachweis eines seglers aus dem Geiseltal (Aves: Apodiformes). Senck. Leth. 78, 211–212 10.1007/BF03042770 (doi:10.1007/BF03042770) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayr G, Peters DS. 1999. On the systematic position of the Middle Eocene swift Aegialornis szarskii Peters 1985 with description of a new swift-like bird from Messel (Aves, Apodiformes). Neues Jahrb. Geol. P M 1999, 312–320 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayr G. 2003. A new Eocene swift-like bird with a peculiar feathering. Ibis 145, 382–391 10.1046/j.1474-919X.2003.00168.x (doi:10.1046/j.1474-919X.2003.00168.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mourer-Chauviré C, Sigé B. 2006. Une nouvelle espéce de Jungornis (Aves, Apodiformes) et de nouvelles formes de Coraciiformes s.s. dans l'Eocène'supérieur du Quercy. Strata 13, 151–159 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mayr G. 2009. Paleogene fossil birds. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mayr G. 2010. Reappraisal of Eocypselus: a stem group apodiform from the early Eocene of Northern Europe. Palaeobiodivers. Palaeoenviron. 9, 395–403 10.1007/s12549-010-0043-z (doi:10.1007/s12549-010-0043-z) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayr G. 2003. Phylogeny of early Tertiary swifts and hummingbirds (Aves: Apodiformes). Auk 120, 145–151 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weis-Fogh T. 1972. Energetics of hovering flight in hummingbirds and in Drosophila. J. Exp. Biol. 56, 79–104 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chantler P. 1999. Family Apodidae (swifts). In Handbook of the birds of the world, vol. 5: barn-owls to hummingbirds (eds del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J.), pp. 388–475 Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenewalt CH, Brandt W, Friel DD. 1960. Iridescent colors of hummingbird feathers. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 50, 1005–1013 10.1364/JOSA.50.001005 (doi:10.1364/JOSA.50.001005) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schuchmann KL. 1999. Family Trochilidae (hummingbirds). In Handbook of the birds of the world, vol. 5: barn-owls to hummingbirds (eds del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J.), pp. 468–680 Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prum RO. 2006. Anatomy, physics, and evolution of avian structural colors. In Bird coloration, vol. 1 (eds Hill GE, McGraw KJ.), pp. 295–353 Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karhu A. 1992. Morphological divergence within the order Apodiformes as revealed by the structure of the humerus. Nat. Hist. Mus. Los Angeles Sci. Ser. 36, 379–384 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bochenski Z, Bochenski ZM. 2008. An Old World hummingbird from the Oligocene: a new fossil from Polish Carpathians. J. Ornithol. 149, 211–216 10.1007/s10336-007-0261-y (doi:10.1007/s10336-007-0261-y) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grande L, Buchheim HP. 1994. Paleontological and sedimentological variation in early Eocene Fossil Lake. Contrib. Geol. 30, 33–56 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ksepka DT, Clarke JA. 2010. Primobucco mcgrewi (Aves: Coracii) from the Eocene Green River Formation: new anatomical data from the earliest constrained record of stem rollers. J. Vert. Paleontol. 30, 215–225 10.1080/02724630903412414 (doi:10.1080/02724630903412414) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith ME, Carroll AR, Singer BS. 2008. Synoptic reconstruction of a major ancient lake system: eocene Green River Formation, western United States. GSA Bull. 120, 54–84 10.1130/B26073.1 (doi:10.1130/B26073.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nesbitt SJ, Ksepka DT, Clarke JA. 2011. Podargiform affinities of the enigmatic Fluvioviridavis platyrhamphus and the early diversification of Strisores (‘Caprimulgiformes’+Apodiformes). PLoS ONE 6, e26350. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026350 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0026350) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayr G. 2009. Phylogenetic relationships of the paraphyletic ‘caprimulgiform’ birds (nightjars and allies). J. Zool. Syst. Evol. Res. 48, 126–137 10.1111/j.1439-0469.2009.00552.x (doi:10.1111/j.1439-0469.2009.00552.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mayr G, Clarke J. 2003. The deep divergences of neornithine birds: a phylogenetic analysis of morphological characters. Cladistics 19, 527–553 10.1111/j.1096-0031.2003.tb00387.x (doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2003.tb00387.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Livezey BC, Zusi RL. 2006. Higher-order phylogenetics of modern birds (Theropoda, Aves: Neornithes) based on comparative anatomy: I. Methods and characters. Bull. Carn. Mus. Nat. Hist. 37, 1–544 10.2992/0145-9058(2006)37[1:PON]2.0.CO;2 (doi:10.2992/0145-9058(2006)37[1:PON]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livezey BC, Zusi RL. 2007. Higher-order phylogeny of modern birds (Theropoda, Aves: Neornithes) based on comparative anatomy: II. Analysis and discussion. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 149, 1–95 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00293.x (doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2006.00293.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson JD, Gibson TG, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. 1997. The ClustalX Windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 4876–4882 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876 (doi:10.1093/nar/25.24.4876) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swofford DL. 2003. PAUP*: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods). Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dyke GJ. 2001. A primitive swift from the London Clay and the relationships of fossil apodiform birds. J. Vert. Paleontol. 21, 195–200 10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0195:APSFTL]2.0.CO;2 (doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0195:APSFTL]2.0.CO;2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mayr G. 2001. The relationships of fossil apodiform birds: a comment on Dyke (2001). Sencken. Leth. 81, 1–2 10.1007/BF03043290 (doi:10.1007/BF03043290) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayr G. 2005. A new cypselomorph bird from the middle Eocene of Germany and the early diversification of avian aerial insectivores. Condor 107, 342–352 10.1650/7596 (doi:10.1650/7596) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chubb AL. 2004. Nuclear corroboration of DNA–DNA hybridization in deep phylogenies of hummingbirds, swifts, and passerines: the phylogenetic utility of ZENK (ii). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 30, 128–139 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00160-X (doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00160-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zusi RL, Bentz GD. 1982. Variation of a muscle in hummingbirds and swifts and its systematic implications. Proc. Biol. Soc. Wash. 95, 412–420 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holmgren J. 1998. A parsimonious phylogenetic tree for the swifts, Apodi, compared with the DNA-analysis phylogenies. Bull. Brit. Ornithol. Club 118, 238–249 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thomassen HA, Wiersema AT, de Bakker MA, de Knijff P, Hetebrij E, Povel GD. 2003. A new phylogeny of swiftlets (Aves: Apodidae) based on cytochrome-b. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 29, 86–93 10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00066-6 (doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00066-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayr G. 2004. Old World fossil record of modern-type hummingbirds. Science 304, 861–864 10.1126/science.1096856 (doi:10.1126/science.1096856) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dyke GJ, Waterhouse DM, Kristoffersen AV. 2004. Three new fossil landbirds from the early Paleogene of Denmark. Bull. Geol. Soc. Denmark 51, 47–56 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Durrer H. 1986. The skin of birds: coloration. In Biology of the integument 2: vertebrates (eds Bereiter-Hahn J, Matoltsky AG, Richards KS.), pp. 239–247 Berlin, Germany: Springer [Google Scholar]

- 45.Clarke JA, Ksepka DT, Salas-Gismondi R, Altamirano AJ, Shawkey MD, D'Alba L, Vinther J, DeVries TJ, Baby P. 2010. Fossil evidence for evolution of the shape and color of penguin feathers. Science 330, 954–957 10.1126/science.1193604 (doi:10.1126/science.1193604) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vinther J, Briggs DEG, Clarke J, Mayr G, Prum RO. 2010. Structural coloration in a fossil feather. Biol. Lett. 6, 128–131 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0524 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0524) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li Q, Gao K-Q, Vinther J, Shawkey MD, Clarke JA, D'Alba L, Meng Q, Briggs DEG, Prum RO. 2010. Plumage color patterns of an extinct dinosaur. Science 327, 1369–1372 10.1126/science.1186290 (doi:10.1126/science.1186290) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Q, et al. 2012. A new reconstruction of Microraptor and the evolution of iridescent plumage color. Science 335, 1215–1219 10.1126/science.1213780 (doi:10.1126/science.1213780) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang F, Kearns SL, Orr PJ, Benton MJ, Zhou Z, Johnson D, Xu X, Wang X. 2010. Fossilized melanosomes and the colour of Cretaceous dinosaurs and birds. Nature 463, 1075–1078 10.1038/nature08740 (doi:10.1038/nature08740) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stolpe VM, Zimmer K. 1939. Der Schwirrflug des Kolibri im Zeitlupenfilm. J. Ornithol. 87, 136–155 10.1007/BF01950821 (doi:10.1007/BF01950821) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pennycuick CJ. 1975. Mechanics of flight. In Avian biology (eds Farner DS, King JR.), pp. 1–75 New York, NY: Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rayner JMV. 1988. Form and function in avian flight. In Current ornithology (ed. Johnston RF.), pp. 1–66 New York, NY: Plenum Press [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nudds RL, Dyke GJ, Rayner JMV. 2004. Forelimb proportions and the evolutionary radiation of Neornithes. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271, S324–S327 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0167 (doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0167) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weidig I. 2010. New birds from the lower Eocene Green River Formation, North America. Rec. Aust. Mus. 62, 29–44 10.3853/j.0067-1975.62.2010.1544 (doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.62.2010.1544) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feduccia A. 1973. A new Eocene zygodactyl bird. J. Paleontol. 47, 501–503 [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mourer-Chauviré C. 1988. Les Aegialornithidae (Aves: Apodiformes) des Phosphorites du Quercy. Comparaison avec la forme de Messel. Cour. For. Sekenbg. 107, 369–381 [Google Scholar]