Abstract

On average, every four minutes an individual dies from a stroke, accounting for 1 out of every 18 deaths in the United States. Apporximately 795,000 Americans have a new or recurrent stroke each year, with just over 600,000 of these being first attack [1]. There have been multiple animal models of stroke demonstrating that novel therapeutics can help improve the clinical outcome. However, these results have failed to show the same outcomes when tested in human clinical trials. This review will discuss the current in vivo animal models of stroke, advantages and limitations, and the rationale for employing these animal models to satisfy translational gating items for examination of neuroprotective, as well as neurorestorative strategies in stroke patients. An emphasis in the present discussion of therapeutics development is given to stem cell therapy for stroke.

Keywords: cerebral ischemia, animals, basic research, translational, clinical application

Patient numbers and current methods of care for stroke

Stroke is the third leading cause of death and the leading cause of long-term disability in the United States [2]. In 2008, the direct and indirect costs of stroke in the United States were estimated to be $34.3 billion, with a direct cost of $18.8 billion [1]. The mean lifetime cost of ischemic stroke to a single patient in the United States is estimated at $140,048; this includes inpatient care, rehabilitation, and follow-up care necessary for lasting deficits [3]. Approximately 2 out of every 1,000 adults will have their first stroke in any given year in the United States [4]. Other than one recombinant protein therapy, the current therapy for stroke is limited [5–8]., Tissue plasminogen activator, or more commonly known as tPA, is the only FDA approved therapy for adults in the dissolution of thrombi in affected blood vessels following a stroke. No other specific treatment is available to treat either focal cerebral ischemia or a global ischemic event. Small molecule therapies such as anti-platelet drugs, anti-coagulants, and statins act as prophylactics and have no immediate benefit following an acute attack. The numbers of affected individuals, the costs necessary to facilitate their care and rehabilitation, all coupled with the lack of therapies, indicate that stroke represents a current significant unmet medical need.

Prominent rodent in vivo stroke models

Appropriate animal models that mimic human disease are imperative in understanding the efficacy of different treatment strategies for the human brain. Before we begin our rationalization for the need of more specific in-vivo models, we would like to take the opportunity to introduce the prominent models currently in place, along with their benefits and limitations. There are two major types of ischemic models, "global" and "local or focal" ischemia. The global ischemic model is produced by ligating the vertebral arteries (2-vessel), carotid arteries (2-vessel), or both (4-vessel) for 5–15 minutes to resemble the condition of cardiac arrest or coronary occlusion in humans [9–11]. Researchers using this model have focused on hippocampal damage to strengthen their relevance for stroke. On the other hand, focal models are widely accepted as replicating many of the stroke symptoms more closely. The pathological consequences are characterized by a primary insult to a specific set of cells within the targeted brain region (called the infarcted core) and secondary affliction involving cell death (i.e., oxidative stress, inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, altered synaptic plasticity) to neighboring tissue (referred to ischemic penumbra or peri-infarct area). The cortex and striatum are the normally targeted brain regions for these focal stroke models, which are produced by ligation or occlusion of the proximal and distal middle cerebral artery (MCA) using sutures/filaments, photothrombotic approaches, and arterial or intracerebral placement of autologous blood and clot-forming agents. Below, we provide some of the more prominent methods for inducing stroke in rodent models, highlighting the need to replicate focal ischemia over global ischemia for increasing the clinical relevance of the models to ischemic stroke [12].

The technique of filamentous arterial occlusion has been established for over two decades now. The procedure involves advancing a filament from the external carotid artery into the middle cerebral artery (MCA) to produce an occlusion [13] in vascular supply to the striatum and cortex. This middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO) results in ischemia progressing to infarction in the brain regions supplied. As this method does not ensure a permanent ligation of the MCA, it serves an integral role in studies requiring reperfusion. However, there are noted limitations with this method including possible incomplete occlusion and hemorrhaging [14]. A slightly more invasive method of MCAO involves a craniotomy to coagulate or ligate the MCA [15]. In follow-up studies, the results of this method demonstrated variable infarct sizes in different strains of rats [16].

Additional in vivo rodent stroke models involve arterial occlusion through thrombus formation. One such established model, photothrombosis, utilizes the photosensitizing dye rose bengal. After injection, irradiating the exposed region with green light (560nm) induces thrombotic plugs [17]. This protocol demonstrates a larger, more consistent infarction in the Sprague-Dawley strain [18]. Another method of thrombus formation involves the intravascular catheter injection of thrombin at the middle cerebral artery; however, this method may also not produce total arterial occlusion [19].

Global ischemia results from the total cessation of cerebral blood flow. These models are considered limited in their translational clinical application as they do not closely approximate the evolution of stroke events in humans aside from cardiac arrest. The procedure for four-vessel occlusion (4-VO) begins with occlusion of the vertebral arteries prior to occluding both common carotids [9], stopping cerebral blood flow. This method is successful in 50–75% percent of animals, likely due to variability in collateral blood supply [20]. A great benefit of this model is the ability for sustained hyperemia upon reperfusion, [20] which serves as an effective paradigm for metabolic studies [21]. The two-vessel occlusion method (2-VO) has more implication in producing forebrain ischemia in rats and gerbils, but has not been adopted well in mice. Occlusion of both common carotid arteries is coupled with hypotension to produce ischemia in the forebrain region [11]. This model also produces more localized regions of damage in the CA1 pyramidal neurons of the hippocampus, caudoputamen, and neocortex [22]. Table 1 summarizes the milestones of development in the aforementioned models chronologically.

Table 1.

Milestones in Preclinical Investigations of Rodent In Vivo Ischemic Models

| Year | Stroke Model |

Species | Technique and investigation |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ### | Global | Rat | Bilateral carotid artery ligation effects on blood flow and the energy state of the rat brain | [8] |

| ### | Global | Rat | Bilateral carotid artery ligation effects on acid-base parameters | [9] |

| ### | Global | Rat | Transient bilateral hemispheric ischemia utilizing a 4-vessel through electrocauterization of the vertebral arteries | [7] |

| ### | Focal | Rat | MCA occlusion through a subtemporal craniectomy | [13] |

| ### | Global | Rat | Bilateral carotid artery clamping residual blood flow effects on long term recovery | [20] |

| ### | Focal | Rat | Photochemical thrombosis with rose Bengal for cerebral infarction | [15] |

| ### | Focal | Rat | Quantification of volumetric cerebral infarction following MCAO using strain, arterial pressure, glucose, and age | [14] |

| ### | Global | Rat | Importance of controlling collateral circulation in four-vessel occlusion | [18] |

| ### | Global | Rat | Protective effects of lowering brain temperature during ischemia | [19] |

| ### | Focal | Rat | Utilization of an intraluminal suture for reversible regional ischemia | [11] |

| ### | Focal | Rat | Histopathological differences of Sprague-Dawley versus Wistar rats in rose bengal photothrombosis | [16] |

| ### | Focal | Rat | Safety and efficacy evaluation of thrombolytic intervention through intraluminal thrombin induced thrombotic ischemia | [17] |

| ### | Focal | Rat | Evaluation of intraluminal thread MCAO reliability | [12] |

| ### | Global/Focal | Various | Review of animal models across various species to investigate the injury mechanisms and neuroprotective strategies | [10] |

Consideration of co-morbidity factors in rodent ischemic stroke models

Ischemic stroke models in rodents include: arterial ligation or occlusion by insertion of sutures or infusion of blood clots using various methods (craniotomy and endovascular), electrocoagulation, photo-thrombosis, and injection of endothelin-1 [13, 23–25]. These models have been successful at mimicking both complete and transient occlusion; however, none precisely mimic a clinical stroke because complete occlusion rarely occurs. Typically, spontaneous recanalization occurs in humans who succumb to strokes. Additionally, the context in which the stroke is produced in the animal models differs in the circumstance in which strokes occur in humans. Often, there are multiple co-morbidity factors: age, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, heart disease, patients’ medications, etc. associated with strokes in the clinic [26–28]. These co-morbidity factors can play a critical role not only in the resulting pathology of the stroke, but also in the response to therapeutics. Accordingly, if these co-morbidity factors are not considered in the animal model of stroke, the resulting pathology, as well as the preclinical readouts of novel therapies, will not closely approximate the clinical setting.

Aging

The process of aging alters the efficacy and safety profiles of many medications through its effects on pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. It interacts with the processes involved in spontaneous recovery and is a risk for hemorrhagic transformation after thrombolytic therapy [29,30]. Most of the rodent stroke models utilize young animals, allowing these juvenile animals with robust brain plasticity better spontaneous recovery and improved response to neuroprotective and neurorestorative treatments after the experimental insult. The major limiting factor in using old animals for disease modeling is their expensive costs. In order to reduce the animal costs, the general research strategy is to initially obtain preliminary data demonstrating therapeutic benefits in young animals. If positive data are achieved, then subsequently proposing old animals for testing the new treatments may be cost effective. Of note, there are studies that have involved older stroke animals [31], and their standardization should facilitate evaluation of functional parameters of stroke and potent therapeutics that are highly relevant to the clinic.

Hypertension

Hypertension is an equally difficult co-morbidity factor to incorporate in animal models of stroke and therapeutics development. Hypertension is the most prevalent risk factor for stroke and has been shown to promote aberrant vascular responses to ischemia that may extend beyond the vasculature and lead to compensatory alterations in the neurovascular unit [32,33]. Although there are many studies demonstrating the key involvement of hypertension in stroke pathology [34], there remains a low number of preclinical investigations of neuroprotection and neurorestoration in hypertensive stroke animals. Literature has established the potential exacerbation of stroke due to a hypertensive platform. With outcomes of therapeutics generated from non-hypertensive animals, a logical translation of these preclinical results is adjusting the target patient population to non-hypertensive stroke patients. However, to increase the patient population who may benefit from new therapeutics, defining the safety and efficacy profiles in hypertensive stroke rats should be considered.

Diabetes

Diabetes and hyperglycemia occur in one-third of acute stroke patients and reduce the likelihood of good recovery after recanalization therapy through complex mechanisms that partly depend on the duration and severity of ischemia and whether parenchymal reperfusion actually occurs. There are also few studies incorporating diabetes and hyperglycemia as co-morbidity factors in assessing potential therapeutics in stroke [35,36]. That a close interaction exists between diabetes and the prognosis of recanalization after ischemia necessitates the need for using diabetic and/or hyperglycemic animals as stroke model especially when the therapeutics being tested possess thrombolytic properties. Indeed, reduced thrombolytic efficacy and higher risk of post-ischemic cerebral hemorrhage are closely associated with post-stroke hyperglycemia and diabetes mellitus [37].

Hyperlipidemia

Hyperlipidemia is characterized by abnormally increased levels of any or all lipids and/or lipoproteins in the blood. Whereas a gene mutation in lipoprotein receptor leads to primary hyperlipidemia, secondary hyperlipidemia is predisposed by other factors such as diabetes. Accumulating evidence has revealed the critical role of hyperlipidemia as a co-morbidity factor in stroke in that hyperlipidemia may exacerbate the host immune response after stroke, thereby aggravating brain ischemia [38]. Although there are many studies examining neuroprotective novel therapies in stroke animals with hyperlipidemia (i.e., high fat diet), there is no laboratory investigation using these animals for evaluating the potential benefits of neurorestoration.

Heart disease

Cardiac arrest has been shown to not only increase the risk of stroke, but also may directly produce cerebral ischemic histological and behavioral deficits. Animal models of global ischemia, which mimic cardiac arrest, induce brain alterations, most notably cell death in the hippocampal region, and in turn resulting in cognitive impairments. While the direct effects of cardiac arrest on stroke have been documented in animal models, cardiac arrest is one of many consequences of heart disease. Moreover, diverse causes of heart disease have been identified, with atherosclerosis as the typical antecedent. Both these consequential events and antecedents, which define heart disease, remain not well studied as co-morbidity factors in stroke pathology and therapeutics development. Despite limited studies on the other co-morbidity factors of heart disease and stroke, there is indication that therapeutics that impart beneficial effects in stroke may also ameliorate pathological events of heart disease and vice versa. Case in point, minocycline shown as neuprotective in cerebral ischemia [39–42] also affords protection against myocardial ischemia and cardiomyopathy [43, 44].

Patient medications

Most animal models of stroke investigating new therapeutics rarely take into account the multi-drug regimen for stroke patients. Many of the co-morbidity factors mentioned above are modifiable risk factors which may be amenable to drug treatments. Stroke patients are likely under medications for hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and heart disease, but very few animal studies have tested new therapeutics in tandem with drugs against one or combination of these co-morbidity factors. With this in mind, the safety and efficacy profiles of the new therapeutics, which are generated using a single or stand-alone preclinical paradigm, do not closely approximate the clinical setting. Of note, preclinical studies of neuroprotection and neurorestoration appear to delineate their treatments within specific time periods post-stroke, with the former limiting the therapeutic window within few to several hours, while the latter extending the treatment initiation to days and even weeks or months after the ischemic episode. Arguably, the lack of continuity of treatments that transgress from the acute, to subacute, and eventually the chronic phase of stroke may be contributing to the failure of translating laboratory products to the clinic. To this end, serious consideration should be given to testing combination therapy of neuroprotection and neurorestoration involving novel drugs and stem cell transplantation, respectively [45].

Limitation of rodent ischemic stroke model

The scarcity of co-morbidity studies in stroke is compounded by the limitation of the rodent stroke model itself. As noted above, there are many models of cerebral ischemia, but the two preferred approaches involve the permanent and transient occlusion or ligation of blood vessels supplying the brain. The middle cerebral artery (MCA) is the standard vessel targeted for occlusion due to its accessibility and the reproducibility of the model. The MCA occlusion and ligation models in rodents produce an acute focal ischemia [13] and are the most popular in producing ischemic strokes [14]. The principal procedure consists of introducing a 4-0 nylon intraluminal suture into the cervical internal carotid artery (ICA) and advancing it intracranially to block blood flow into the MCA; collateral blood flow is reduced by interrupting all branches of the external carotid artery and all extracranial branches of the ICA. In some groups of rats, bilateral vertebral or contralateral carotid artery occlusion is also performed. Several variations to this procedure have been proposed [46,47]. Despite the popularity of the procedure, it does have many limitations, which may include a high rate of variability with location and size of the lesion. [14, 48–52]. One factor that contributes to the above limitations is the inability to visualize the placement of the MCA occluder. Thus, a miscalculation of the MCA origin is expected to be a common occurrence that may contribute to variability in lesion volume outcomes. Laser Doppler flowmetry (LDF) can improve the reliability of occluder placement; however, LDF provides information on the relative decrease in blood flow at only a single point, thereby making it difficult to determine whether the territory is fully or only partially occluded [53]. Other modes of inciting the stroke are reserved for larger animals in which craniotomy can be performed and vascular access for endovascular techniques are more suitable.

Many models used for acute stroke neuroprotection studies employ functional assays for determining safety and efficacy profiles with short animal survival times [54]. For stroke neurorestoration studies, in order to capture the chronic stage of the disease, longer animal survival periods are utilized to reveal safety and efficacy profiles of the new therapeutics. Another limitation for using rodents as an animal for stroke models is the variability in the vascular supply when compared to humans. The anatomy of non-human primate (NHP) closely resembles the human brain, thus is likely to result in pathophysiological abnormalities reminiscent of human stroke. The technical limitations of the rodent stroke models, however, need to be equally assessed with the logistical and practical advantages in that they typically do not require the expensive cost and maintenance inherent with larger animal models of stroke. Accordingly, a larger sample size can be studied in rodent models, which is difficult to accomplish in the expensive NHP models. Notwithstanding, ideal translational study designs must consider sample size, randomization, investigator bias, and treatment condition blinding, all of which should constitute good practice measures to avoid confounding variables that may limit the successful translation of laboratory findings to clinical outcomes [55, 56]. An effort to develop animal models most closely resembling the clinical setting should be explored in order to better approximate the safety and efficacy of new therapeutics for stroke.

Non-Human Primates for Ischemic Stroke Models

This section presents a scientific platform for determining the benefit of stem cell therapy in stroke, highlighting the need to develop an NHP ischemic stroke model in defining a clinically relevant therapeutics development strategy. Subsequent sections will initially provide a snapshot of the recent advancements of cell transplantation and a rationale for their potential therapeutic effects, necessitating the need for predictive NHP stroke models. We will then discuss the current NHP stroke models while identifying their limitations.

Recent studies on cell transplantation, cell fate, and benefit in the CNS in ischemic injury models

Recently, cell transplantation therapies and stem cell treatments have come into focus as potential treatments for numerous diseases and medical conditions, including stroke. One approach using stem cells involves the direct transplantation of neural stem cells (NSCs) into the damaged region of the brain. NSCs transplanted following transient global ischemia differentiated into neurons and improved spatial recognition in rats [57]. Post-mitotic neuron-like cells (NT2N) cells, derived from a human embryonal carcinoma cell line, migrated over long distances after implantation into brains of immuno-competent newborn mice and differentiated into neuron-like and oligodendrocyte-like cells [58]. NT2N cells promoted functional recovery following focal cerebral ischemia after direct transplantation [59]. Similarly, MHP36 cells, a stem cell line derived from mouse neuroepithelium, improved functional outcome in rats after global ischemia [60] and also following focal cerebral ischemia or stroke [61]. NCSs grafted into brain developed morphological and electrophysiological characteristics of neurons [62].

Other direct transplantation experiments in the brain have utilized cells derived from bone marrow. Bone marrow stromal cells (MSCs), when injected into the lateral ventricle of the brain, migrated and differentiated into astrocytes [63]. Fresh bone marrow transplanted directly into the ischemic boundary zone of rat brain improved functional recovery from middle cerebral artery occlusion [64]. Similarly, MSCs implanted into the striatum of mice after stroke, improved functional recovery [65]. MSCs differentiated into presumptive neurons in culture [66] and assumed functional neuronal characteristics in embryonic rats [67]. Intracerebral grafts of mouse bone marrow also facilitated restoration of cerebral blood flow and blood-brain barrier after stroke in rats [68].

Indirect transplant methods, via intravenous or intra-arterial injection, have demonstrated positive effects. Peripherally injected tagged bone marrow stem cells were shown to differentiate into microglia and astrocytic-like cells [69], as well as putative neurons and endothelial cells after MCA occlusion [70]. Intra-carotid administration of MSCs following MCA occlusion in a rat model improved functional outcome [71]. Intravenous administration of MSCs has also been found to induce angiogenesis in the ischemic boundary zone following stroke in rats [72]. Similarly, intravenous administration of umbilical cord blood ameliorated functional deficits after stroke in rats [73]. Intravenous administration of cord blood is more effective than intra-striatal administration in producing functional benefits following stroke in rats [74].

Mechanistic interpretation of therapeutic benefit involving stem cells

The mechanism underlying the benefit from stem cell transplantation remains to be determined. One possibility is the transformation of the transplanted cells into neurons [75]. There appears to be a positive relationship between the degree of behavioral improvement and the number of transplanted cells that stain positive for neuron specific markers [58]. However, transplanted cells often do not develop normal processes, and thus the benefit may not be mediated only by neuronal circuitry [76].

An alternative hypothesis, that is not mutually exclusive, is that the transplanted cells may also assist via differentiation into neuroectodermal derived cell types other than neurons. MSCs have been demonstrated to migrate and transform into astrocytes [63]. Hematopoietic cells can differentiate into microglia and macroglia [69]. Bone marrow derived stem cells may also assist in blood vessel regeneration following brain tissue damage in several ways. The stromal cell derived factor-1 (SDF-1)/CXCR4 system assists in integration of cells into injured tissue by promoting the adhesion of CXCR4-positive cells onto vascular endothelium [77]. SDF-1 also augments vasculogenesis and neo-vasculogenesis of ischemic tissue by recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells [78]. Bone marrow is a source of these endothelial progenitors [79]. Adult bone marrow-derived cells have been shown to participate in angiogenesis by the formation of periendothelial vascular cells [80]. Intravenous administration of MSCs induced angiogenesis in the ischemic boundary zone after stroke [72]. It has also been observed that crude bone marrow is a source of endothelial cells after experimental stroke [70].

In addition to the mechanisms above, trophic factors produced by the transplanted cells could be of contribution. Via this mechanism, bone marrow grafts may assist in restoring brain blood flow and also the blood brain barrier [68]. Trophic factors from marrow stromal cells may play a role in brain repair itself. Recent evidence suggests that intravenous administration of MSCs increases the expression of nerve growth factor and brain-derived neurotrophic factor following traumatic brain injury [81]. Understanding the exact mechanism(s) responsible for the therapeutic benefit seen following stem cell transplantation in the CNS will be important in extending the potential uses for stem cell therapies in the near future.

Rationale for developing an NHP ischemic model to test therapeutic potential of stem cell therapy in stroke

In line with the tenets of a translational approach aimed at facilitating the entry of stem cell products from the laboratory to the clinic, testing the potential benefits of stem cell therapy in a large animal model of stroke has been considered. The major concern with any NHP cerebral ischemia model is the scarcity of rigorous data characterizing the ischemic brain cell death in this model to justify its use for validation of stem cell therapy in stroke. Scientific guidance is much needed on how to best approach the issue of using NHP models of transient global ischemia (TGI), as well as focal ischemia and normal NHPs in evaluating the safety and efficacy of stem cell therapy. First, we acknowledge here the limitations of NHP global ischemia. Inflammation, one of the cell death exacerbating factors normally accompanying cerebral ischemia, has not been established as a contributory component on the evolution of the stroke pathology in NHP global ischemia model. In contrast, inflammation has been shown to be closely associated with NHP focal ischemia progression. Although the study of stem cells in this NHP global ischemia model with emphasis on brain alteration is interesting, it would appear more logical and more informative to pursue a focal (i.e., brain) ischemia model. However, in addition to logistical issues (stem cell preparation and their subsequent histological evaluations), the limiting factor with incorporating the NHP focal ischemia in a translational research strategy is that there is much concern on how the current focal ischemia model will address the “safety” and “efficacy” outcomes proposed in our study. Citing the February 2006 American Stroke Association symposium on stem cells and NHPs, there are clear-cut questions against the validity at this time of available NHP stroke models (either focal or TGI) for evaluation of safety and efficacy of stem cell therapy. The scarce literature on NHP stroke model investigating stem cell therapy indicates that it is not the ripe time to proceed with this focal ischemia model to evaluate safety and efficacy of stem cell therapy. A major concern is the field does not really know how the NHP stroke pathology will react to stem cells. Will the stem cells migrate to the site of injury? Will functional stem cells persist in the stroke brain? Will the host microenvironment be conducive to the stem cells? Such outcome measures need to be in place first and foremost, before one can begin testing safety and efficacy of stem cells. These “mechanistic” questions need to be resolved prior to embarking in translational safety and efficacy studies in this NHP stroke model.

Second, if the NHP stroke model is still in its infancy to warrant its use in stem cell validation, then the use of normal NHPs may pose as an alternative approach in that one can do a straight toxicology study. However, with accumulating evidence indicating that the practical route of administration of stem cells in the clinical setting is via the peripheral route (i.e., intravenous), it is unlikely that stem cells will migrate to the “normal” brain. Although one can harvest the brain and other peripheral organs to characterize where the cells have lodged, and if a toxic pathology is recognized, we realize that such “fishing expedition” is clearly not the logical approach to evaluate stem cell therapy in NHPs. Moreover, while such approach will provide partial “safety” and “toxicology” issues, the obvious difference in stroke pathology and non-stroke “normal” pathology will remain a major issue and will not fully answer the question on how stem cells and the stroke host microenvironment interact with each other and how such stem cell-host interaction contributes to the resulting stroke pathology and stem cell functionality.

Based on the above arguments highlighting the current lack of data to support either the TGI or focal NHP stroke model as an established platform for evaluating stem cell safety and efficacy, coupled with the limited informative knowledge that we can gain if we were to use normal NHPs, consideration is given to the NHP TGI model primarily to resolve these issues and will provide reliable outcome measures to reveal 1) NHP stroke pathology with particular emphasis on ischemic cell death cascade, including inflammation and apoptosis, 2) whether such pathologic (i.e., ischemic) NHP microenvironment allows stem cell functionality, including their migratory and proliferative or tumorigenic potential, and 3) whether the grafted stem cells correct or exacerbate the stroke pathology. A major limitation of using NHPs in modeling stroke (or practically any human disease) is that while an NHP model will provide a reasonable likelihood of giving enough “quantitative” data to support the outcome measures of TGI and stem cell persistence, it will be challenging to reasonably estimate the needed NHP sample size for statistical analyses.

The development of a stroke model in a large animal is in concert with the scientific community’s serious attempt to test “experimental stroke therapies” within the translational study concept in accordance with the Stroke Treatment Academic Industry Roundtable or STAIR [82]. The criteria defined by STAIR have focused on necessary steps in pre-clinical development to avoid a clinical translational failure, including defining the timing or window of therapeutic benefit, the optimal route of administration, as well as demonstration of dose response data and making sure that these doses are achievable safely in humans. The other STAIR requirement to demonstrate the potential of stem cell therapy in a second animal stroke species is addressed by pursuing this NHP model. Finally, there are a few research teams in the US who have similarly develop a stroke model in large animals in testing experimental therapies, including stem cell transplantation. However, to date, the NHP model used in these cell transplant studies appears highly invasive. We highlight here that the TGI model has a major advantage of being a more humane procedure than other stroke models for survival procedures because it leaves the subject without a cranial defect and the related potential disabilities.

An overview of NHP stroke models

As we have previously mentioned, despite their benefits, rodent stroke models still present limitations in translational research. There are numerous benefits to using nonhuman primate models, of particular is their vascular anatomy, they are gyrencephalic, the ability to target the basal ganglia through occlusion, and their size subjects them to testing by human clinical techniques such as: CT, MRI, angiography, and more [83]. However, despite these advantages, the use of animal models for stroke is usually relegated to rodents. Here, we will expand upon some established primate models, along with their benefits and limitations. Table 2 captures the chronological milestones in developing many of the most prominent in-vivo ischemic models for non-human primates.

Table 2.

Milestones in Preclinical Investigations of NHP In Vivo Ischemic Models

| Year | Species | Technique and investigation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| ### | Macaque | Temporary intracranial occlusion of the MCA proximal to the primary motor cortex to produce neuropathology | [119] |

| ### | Macaque | Permanent intravenous embolization of segmental MCA occlusion in the primary motor cortex as a stroke model without craniotomy | [120] |

| ### | Baboon | Permanent transorbital clipping proximal/distal to primary motor cortex to obstruct cerebral blood flow | [121] |

| ### | Baboon | Temporary transorbital balloon occluder proximal to primary motor cortex for stroke model under awake conditions | [122] |

| ### | Macaque | Snare ligation for reversible focal ischemia proximal to the primary motor cortex | [123] |

| ### | Baboon | Retro-orbital coagulation of the lenticulostriate artery for basal ganglia occlusion | [124] |

Global ischemic injury following circulatory arrest had long been recognized to cause alterations on the human brain [84]. However, a better understanding of the pathology required the development of appropriate NHP models [85–87]. Currently, squirrel monkeys, macaques, and baboons have been utilized for nonhuman primate stroke models. Early stroke studies demonstrated consistent cortical and striatal pathology. This discovery of delayed neuronal death in rodent hippocampus after global ischemia [88–90] prompted interest in revealing a similar phenomenon in the primate brain. The pioneering study by Zola-Morgan and colleagues showed a CA1 sector lesion in a patient who had suffered from a transient global ischemic insult during cardiac surgery [91]. Subsequent studies by this group reported three similar clinical cases of hippocampal (mainly CA1) lesions [92]. The common neuropathological finding among these four patients, highlighting the bilateral disappearance of CA1, was accompanied by memory deficits. The initial pathological CA1 alterations were initially verified histologically [93], and recently confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging [94]. These human studies underscore the clinical significance of delayed neuronal death, warranting further evaluation of this phenomenon in NHP models. To this end, applying a nonsurgical model, i.e., hypotension induced by neck cuffing, Zola-Morgan and coworkers reported a marked neuronal loss in CA1 sector and partial loss in CA2 and CA4 sectors in six monkeys with accompanying memory loss [95]. Such localized cell loss producing a brain dysfunction suggests that the hippocampus stands as a focal site of cerebral ischemia, in that limited damage to this structure is sufficient to impair memory [95]. Pursuing an alternative approach involving surgical occlusion of all eight major arteries supplying blood to the brain, Tabuchi and colleagues obtained similar results, and showed that an occlusion lasting 15 min produced damage that was localized to the hippocampus [96, 97].

Recent studies by Yamashima and co-workers [98–101] have standardized a minimally invasive global ischemia procedure in Japanese macaques via 15 min ligation of the subclavian and innominate arteries producing consistent hippocampal cell loss. In our desire to translate experimental therapeutics for cerebral ischemia from the laboratory to the clinic, we maintain the need to test these treatment strategies in ischemic monkeys. The accumulating evidence of focal ischemic cell loss in NHPs following exposure to transient global ischemia prompted examination as to whether the Rhesus macaque, compared to the Japanese macaque, would similarly exhibit hippocampal damage [102–105].

Transient global ischemia

The transient global ischemia surgical model, which is induced by clipping both the innominate and left subclavian arteries, has been described in detail previously [100, 106]. The ischemia surgery is carried out under general anesthesia. Animals are sedated with ketamine (10mg/kg) IM and preanesthetized with Atropine (0.02 mg/kg) SC. The animals are then intubated with an appropriately sized endotracheal tube, and anesthetized with 2% isoflurane by a respirator prior to the surgical procedure. Body temperature is monitored with a rectal probe and maintained within normal physiological limits (36.5–38.50C) using a warming blanket. Body temperature, pupil size, respiratory rate, and SPO2 are monitored throughout the surgical procedure. To achieve transient forebrain ischemia, both the innominate artery and the left subclavian artery are initially exposed in the midiastinum by removing the sternum, and then they are clipped with two vascular clamps under the normotension of 80–100 mmHg. Use of the 15–20 minute occlusion model works consistently in Japanese macaques [100].

In our previous study [107], NHPs exposed to 15-min of ischemia exhibited minor hindlimb paralysis, and by 48 hours after ischemia, animals appeared fully recovered with only minor fine motor deficits. Their HE stains of hippocampi reveal marked cell loss and reduction of cell layers in day 5 and day 30 post-ischemic animals, while the hippocampal region in day 1 postischemic animal appeared intact with no discernable reduction in cell number and layer compared to the normal animal. The ischemic cell death detected in the hippocampi was characterized by eosinophilic cells with condensed or pyknotic nuclei with a reddish cytoplasm. Nissl stains mimicked the HE staining pattern demonstrating that ischemic cell loss in the hippocampi of day 5 and day 30 post-ischemic animals was characterized by chromatolysis. In contrast, the hippocampal region of the normal animal or the day 1 post-ischemic animal did not reveal any detectable cell loss. Healthy-looking MAP2 positive cells along the hippocampus of day 1 post-ischemic animal and normal animal were recognized. However, an obvious reduction in MAP2 positive cells and a disappearance of 2–3 layers of the hippocampus were seen in day 5 and day 30 post-ischemic animals. GFAP immunostaining revealed GFAP positive reactive glia in the hippocampus of animals euthanized at day 5 post-ischemic hippocampus, which was maintained up to day 30 post-ischemia. However, such glia activation was not evident in the hippocampus of animal euthanized at day 1 post-ischemia animal or the normal animal. Lack of TUNEL labeling was observed in the hippocampi of animal euthanized at day 1 post-ischemia and normal animal. In contrast, TUNEL-positive apoptotic cells were detected in the hippocampi of day 5 and 30 post-ischemia animals [100, 106].

Synopsis of the TGI model

The data from our study [107] discussed above provides immunohistochemical evidence that transient global ischemia renders Rhesus macaques to exhibit neuronal cell loss, reduction in cell layers, and delayed cell death (i.e., apoptosis) in the hippocampus, resembling the histopathological damage seen in Japanese macaques exposed to the same ischemic insult. These observations support the use of this animal species for producing a cerebral ischemia model to test experimental therapies for stroke, especially treatments that may have potential benefits in attenuating secondary apoptotic cell death or those with indications of ameliorating ischemic hippocampus-mediated behavioral deficits such as cognitive impairments.

Limitations of in-vivo nonhuman primate stroke models

As noted above, a major advantage of this transient global ischemia is its less invasive approach, compared to other models, such as bilateral carotid and vertebral artery occlusion [96], cortical electrocoagulation technique [108], or the proximal middle cerebral artery (MCA) occlusion [109, 110], making it a more humane method for producing stroke. For example, the MCA occlusion leaves the subject with a cranial defect and likely with related behavioral dysfunctions [83], whereas the electrocoagulation approach requires a long surgical procedure and entails constant physiological monitoring [111]. The present transient global ischemia thus offers an alternative approach to other less invasive focal stroke procedures including the transorbital approach [112], the reversible ligation of the MCA [93] or the bone flap M1 segment occlusion of the MCA (in marmosets) [113]. The only complication identified with the transient global ischemia model is pneumothorax. However, this complication can be avoided by covering the visceropleura of the lung with a sterile and non-adhesive rubber after removal of the sternum. Other than the visceropleura, there is not any other critical organ exposed near the vicinity of the operative field, thereby limiting any additional complications. For clipping the innominate and subclavian arteries, the procedure is achieved without the need for complicated surgical maneuvers. First, the innominate artery can be easily recognized by its pulsation. Second, after dissecting the innominate artery, the aortic arch can be clearly visualized. Third, by advancing along the distal aorta, one should be able to locate the branch corresponding to the left subclavian artery. By using microclips to clamp the innominate and the subclavian arteries, one would achieve complete ischemia because the arteries perfusing the whole brain (bilateral common carotid and vertebral arteries) originate from these two arteries proximally along the aortic arch. The 15-min ischemia allows rapid recovery of the animal requiring only routine standard of care during the immediate post-surgery period.

The induction of the TGI model is different from the clinical situation of brain ischemic attack and may likely be a more suitable model for cardiac arrest. Despite this shortcoming, the cell death that ensues after the initial blood flow interruption is reminiscent of stroke-induced cell loss in discrete brain regions, especially the hippocampus. Moreover, initial evaluation of behavioral deficits (e.g., memory decline) in the animals exposed to the present transient global ischemia recapitulates the cognitive impairment seen in stroke patients [114]. There are a number of reasons to support the use of the NHP model, specifically the relevance of its features to cerebral ischemia pathology. The existence of ischemic neuronal loss in discrete brain regions following transient global ischemia/reperfusion has been described and confirmed in Japanese macaques, and now is extended in Rhesus macaques. The consistency of these ischemic events within the hippocampus following transient global ischemia in several Japanese macaques (>200) supports the value of this preparation.

The restrictions imposed by models involving rodents and other species to the study of the molecular events of ischemia limits their use in translational research. Significant differences between rodent and primate anatomy further necessitates testing of therapeutic strategies in the latter model. A singular advantage of the NHP is the opportunity to directly apply agents under development for use in humans, prior to their extension to the clinical arena. A highly relevant new aspect of transient global ischemia modeling is the significantly greater consistency and stable neuronal injury in the primate hippocampus compared to the rat brain. In summary, it is demonstrated that the hippocampus in Rhesus macaques is vulnerable after a 15-min transient global ischemia. This minimally invasive ischemia model produces neuronal cell death, apoptosis, and reactive gliosis. More importantly, this NHP model can serve as a platform for investigations of experimental treatments for stroke.

Conclusions

The NHP TGI model produces global ischemia, which is different from the focal ischemia employed in rodents for modeling ischemic stroke. There are practical and scientific rationales behind this decision to pursue a transient global ischemia. The practical reason is primarily based on this global ischemia model as being minimally invasive, therefore avoiding the trauma usually associated with the craniotomy focal ischemic model, with the former allowing long-term survival (months or years) with minimal veterinary care, whereas the latter usually leads to significant morbidity requiring constant veterinary care throughout the survival period. Currently, controversies surrounding the focal ischemic NHP model have led to an all-time high public scrutiny of such NHP models throughout the US and around the world. This concern has even gone beyond public scrutiny, derailing scientific careers as well as endangering lives of the investigators. While not sacrificing the scientific value that one can learn from the focal ischemia, the minimally invasive global ischemia model accomplishes many of the pathological manifestations of the focal ischemia model. As noted above, the TGI model described demonstrates a preferential cell loss in the hippocampus with varying degrees of cell death in other brain areas, providing us with the scientific rationale to examine the brain pathology in this TGI model.

The NHP TGI model will serve as the platform for demonstrating the safety profile of stem cells, whereas the rodent focal ischemic stroke model will be adequate to provide efficacious data. Although the primary aim of the NHP TGI model is to evaluate the safety of stem cell therapy, some indications on the potential benefits of the transplanted stem cells will likely be obtained. While the ischemic hippocampus represents the major brain region of interest that we will focus on characterizing the safety of stem cells, additional brain areas will also be examined. As noted above, the most vulnerable ischemic area to the global ischemia is the hippocampus (>90% cell loss), but this model is also able to produce about 50% and 65% ischemic cell loss in the caudate, putamen, and cortex [115], which are the ischemic areas produced by focal ischemia. In this regards, we will be able to assess the safety of stem cell grafts in the ischemic caudate, putamen, and cortex.

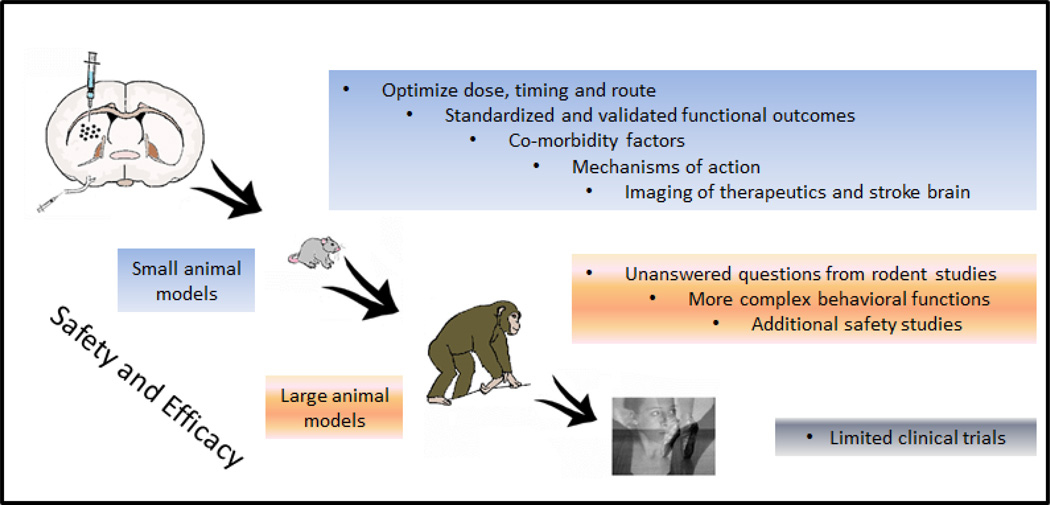

In concert with the STAIR criteria, the guidelines set forth by Stem cell Therapeutics as an Emerging Paradigm for Stroke or STEPS [116–119] also provide the basis for exploring stroke animal models for translating cell-based therapeutics from the laboratory to the clinic. As highlighted in STEPS, the use of appropriate species and clinically relevant stroke animal models, including NHPs, is critical to testing the potential of anti-stroke therapeutics (Figure 1). Larger animals, preferably in an NHP, are desirable, but given the scarcity of an established NHP stroke model, safety rather than efficacy may be the more appropriate outcome measures. An overarching premise of the STEPS is that different types of surgical approaches are available, but the “endpoint” rather than the “technique employed” is critical in producing the stroke. The resulting pathophysiological manifestations of each stroke model should mimic the human disease condition as closely as possible in order to enhance the successful translation of novel therapeutics from the laboratory to the clinic [117, 118]. This issue of stroke technique is highly relevant to the limitations of the TGI model which uses a surgical approach that does not represent an ischemic stroke model. However, of particular interest in the TGI model is the pathophysiological endpoint in the Rhesus monkey which is characterized by focal ischemia to the hippocampus. The induction of the TGI model is different from the clinical situation of brain ischemic attack and may likely be a more suitable model for cardiac arrest. Despite this shortcoming, the cell death that ensues after the initial blood flow interruption is reminiscent of stroke-induced cell loss in discrete brain regions, especially the hippocampus. Thus, the TGI model recapitulates the endpoint of ischemic stroke. In addition, since the goal of this TGI model is to test therapeutics in a restoration paradigm rather than a neuroprotection setting, the concept is not to abrogate cell death events leading to ischemic stroke, but rather to repair the brain after the endpoint of ischemic stroke has been established.

Figure 1. Translational Step-Wise Experimental Design for Stroke Neurotherapeutics.

Based on STAIR and STEPS criteria, preclinical experimental designs should emphasize the need to demonstrate safety and efficacy of novel therapeutics in clinically relevant animal models. Small animal models should optimize the dose, timing, and route of delivery of therapeutics by using standardized and validated functional outcomes involving behavioral and histological endpoints that are able to capture stroke symptoms with clinical predictive value. To date, most stroke models have not incorporated co-morbidity factors, such as diabetes and hypertension, and their inclusion to testing novel therapeutics will be important to bolster clinical relevance. Recent guidance from the FDA has also indicated the need to better reveal mechanisms of action, as well as imaging of the therapeutics and the stroke brain. In case questions remained unanswered in small animal models (e.g., white matter injury in humans cannot be fully replicated in rodents), the need to explore large animal models, such as NHPs, will further reveal safety and efficacy of the novel therapeutics. In summary, these preclinical studies should be geared towards the successful translation of the envisioned product from the laboratory to the clinic.

Every effort should be considered in utilizing a standard-of-care therapy (i.e., tPA, rehabilitation therapy) as control group for translational studies. Although such “best in class” control has been accommodated in small animals (rodents, rabbit), the challenge is extending this treatment condition in NHPs. In part, the difficulty in extending such control group is the standardization of tPA treatment and rehabilitation therapy in large animal models in the laboratory testing the experimental therapeutics as it would require an NHP research expert in tPA treatment and rehabilitation therapy. To circumvent this, we propose a collaborative effort by enlisting such expert in translational research.

In choosing the potential therapeutic windows in the different species employed for stroke modeling, initial consideration should be given on the experimental therapeutic’s mechanism of action (MOA), and subsequently choose the stroke model and the species that will be appropriate to test this MOA. In this case, if the therapeutic’s MOA targets the neuroprotective stage, then the therapeutic window will be likely within the acute stage of stroke. In the same token, if the therapeutic’s MOA targets the neurorestorative stage, then the therapeutic window will be likely during the subacute and chronic stage of stroke. In general, small species, such as rodents, have been employed for testing therapeutic windows in acute, subacute, and chronic stages of stroke. The ease in post-operative care largely contributes to the use of small species in almost every stage of stroke. In contrast, large animal models of stroke, such as NHPs, require laborious post-operative care. In addition, as noted above the standardization of NHP stroke models, especially the chronic stage, warrants more investigations, which may limit their use in testing therapeutic windows of experimental modalities within acute and subacute stages of stroke.

Recently, the integration of RIGOR guidelines, in addition to the recommendations by STAIR and STEPS has been proposed for translational research. The RIGOR guidelines were proposed by the NIH National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke to ensure worldwide uniformity in stroke research practices. Many similarities abound in the guidelines recommended by STAIR, STEPS, and RIGOR, foremost is the adherence to good laboratory (GLP) practices, including the need for all animal modeling studies to pursue treatment condition blinding, randomization, and complete power analysis and statistical analysis [120]. Moreover, these GLP practices should be clearly stated when submitting translational grant applications and manuscripts [120]. Of note, Translational Stroke Research and the Journal of Neurology and Neurophysiology have established this policy in their manuscript submissions. In the end, many animal models of stroke exist, but there is a need to continue refining these models so that they may accurately reflect our ability to test treatments that have the potential for clinical therapy. Equally important in this quest to find the optimal in vivo animal model is to establish a transparency of any investigator’s conflict of interest that may potentially bias the study report [120].

Acknowledgments

The Borlongan Laboratory is supported by NIH NINDS UO15U01NS055914-04, NIH NINDS R01NS071956-01, James and Esther King Foundation for Biomedical Research Program, USF Signature Program in Interdisciplinary Neuroscience, SanBio Inc., Celgene Cellular Therapeutics, KMPHC, and NeuralStem Inc. CVB has patents and pending patents on cell therapy.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

References

- 1.Roger VL, et al. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics--2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(1):188–197. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182456d46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davenport R, Dennis M. Neurological emergencies: acute stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68(3):277–288. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.68.3.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor TN, et al. Lifetime cost of stroke in the United States. Stroke. 1996;27(9):1459–1466. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.9.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sudlow CL, Warlow CP. Comparing stroke incidence worldwide: what makes studies comparable? Stroke. 1996;27(3):550–558. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.3.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagan SC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. NINDS rt-PA Stroke Study Group. Neurology. 1998;50(4):883–890. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.4.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hess DC, et al. REACH: clinical feasibility of a rural telestroke network. Stroke. 2005;36(9):2018–2020. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000177534.02969.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang S, et al. Remote evaluation of acute ischemic stroke in rural community hospitals in Georgia. Stroke. 2004;35(7):1763–1768. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000131858.63829.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borlongan CV, et al. Gene therapy, cell transplantation and stroke. Front Biosci. 2006;11:1090–1101. doi: 10.2741/1865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pulsinelli WA, Brierley JB. A new model of bilateral hemispheric ischemia in the unanesthetized rat. Stroke. 1979;10(3):267–272. doi: 10.1161/01.str.10.3.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eklof B, Siesjo BK. The effect of bilateral carotid artery ligation upon the blood flow and the energy state of the rat brain. Acta Physiol Scand. 1972;86(2):155–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1972.tb05322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eklof B, Siesjo BK. The effect of bilateral carotid artery ligation upon acid-base parameters and substrate levels in the rat brain. Acta Physiol Scand. 1972;86(4):528–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1972.tb05354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Traystman RJ. Animal models of focal and global cerebral ischemia. ILAR J. 2003;44(2):85–95. doi: 10.1093/ilar.44.2.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longa EZ, et al. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion without craniectomy in rats. Stroke. 1989;20(1):84–91. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmid-Elsaesser R, et al. A critical reevaluation of the intraluminal thread model of focal cerebral ischemia: evidence of inadvertent premature reperfusion and subarachnoid hemorrhage in rats by laser-Doppler flowmetry. Stroke. 1998;29(10):2162–2170. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.10.2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tamura A, et al. Focal cerebral ischaemia in the rat:1. Description of technique and early neuropathological consequences following middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1981;1(1):53–60. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1981.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duverger D, MacKenzie ET. The quantification of cerebral infarction following focal ischemia in the rat: influence of strain, arterial pressure, blood glucose concentration, and age. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1988;8(4):449–461. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1988.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watson BD, et al. Induction of reproducible brain infarction by photochemically initiated thrombosis. Ann Neurol. 1985;17(5):497–504. doi: 10.1002/ana.410170513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markgraf CG, et al. Comparative histopathologic consequences of photothrombotic occlusion of the distal middle cerebral artery in Sprague-Dawley and Wistar rats. Stroke. 1993;24(2):286–292. doi: 10.1161/01.str.24.2.286. discussion 292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Z, et al. A new rat model of thrombotic focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1997;17(2):123–135. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199702000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pulsinelli WA, Buchan AM. The four-vessel occlusion rat model: method for complete occlusion of vertebral arteries and control of collateral circulation. Stroke. 1988;19(7):913–914. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.7.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Globus MY, et al. Intra-ischemic extracellular release of dopamine and glutamate is associated with striatal vulnerability to ischemia. Neurosci Lett. 1988;91(1):36–40. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith ML, et al. Models for studying long-term recovery following forebrain ischemia in the rat. 2. A 2-vessel occlusion model. Acta Neurol Scand. 1984;69(6):385–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1984.tb07822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Crespigny AJ, et al. Acute studies of a new primate model of reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;14(2):80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sasaki M, et al. Development of a middle cerebral artery occlusion model in the nonhuman primate and a safety study of i.v. infusion of human mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e26577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher M, et al. Update of the stroke therapy academic industry roundtable preclinical recommendations. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2244–2250. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.541128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi S, Morike K, Klotz U. The clinical implications of ageing for rational drug therapy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64(2):183–199. doi: 10.1007/s00228-007-0422-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hurn PD, Vannucci SJ, Hagberg H. Adult or perinatal brain injury: does sex matter? Stroke. 2005;36(2):193–195. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000153064.41332.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hattiangady B, Rao MS, Shetty AK. Plasticity of hippocampal stem/progenitor cells to enhance neurogenesis in response to kainate-induced injury is lost by middle age. Aging Cell. 2008;7(2):207–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00363.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(24):1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iadecola C, Davisson RL. Hypertension and cerebrovascular dysfunction. Cell Metab. 2008;7(6):476–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindner MD, et al. Long-lasting functional disabilities in middle-aged rats with small cerebral infarcts. J Neurosci. 2003;23(34):10913–10922. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10913.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Girouard H, Iadecola C. Neurovascular coupling in the normal brain and in hypertension, stroke, and Alzheimer disease. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100(1):328–335. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00966.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fisher M. Stroke and TIA: epidemiology, risk factors, and the need for early intervention. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14(6 Suppl 2):S204–S211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rewell SS, et al. Inducing stroke in aged, hypertensive, diabetic rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30(4):729–733. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruno A, et al. Admission glucose level and clinical outcomes in the NINDS rt-PA Stroke Trial. Neurology. 2002;59(5):669–674. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.5.669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martini SR, Kent TA. Hyperglycemia in acute ischemic stroke: a vascular perspective. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27(3):435–451. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fan X, et al. A rat model of studying tissue-type plasminogen activator thrombolysis in ischemic stroke with diabetes. Stroke. 2012;43(2):567–570. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.635250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim E, et al. CD36 in the periphery and brain synergizes in stroke injury in hyperlipidemia. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(6):753–764. doi: 10.1002/ana.23569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu L, et al. Low dose intravenous minocycline is neuroprotective after middle cerebral artery occlusion-reperfusion in rats. BMC Neurol. 2004;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fagan SC, et al. Optimal delivery of minocycline to the brain: implication for human studies of acute neuroprotection. Exp Neurol. 2004;186(2):248–251. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Machado LS, et al. Delayed minocycline inhibits ischemia-activated matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 after experimental stroke. BMC Neurosci. 2006;7:56. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-7-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsukawa N, et al. Therapeutic targets and limits of minocycline neuroprotection in experimental ischemic stroke. BMC Neurosci. 2009;10:126. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-10-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romero-Perez D, et al. Cardiac uptake of minocycline and mechanisms for in vivo cardioprotection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(13):1086–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matsumoto Y, Park IK, Kohyama K. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9, but not MMP-2, is involved in the development and progression of C protein-induced myocarditis and subsequent dilated cardiomyopathy. J Immunol. 2009;183(7):4773–4781. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Glover LE, et al. A Step-up Approach for Cell Therapy in Stroke: Translational Hurdles of Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells. Transl Stroke Res. 2012;3(1):90–98. doi: 10.1007/s12975-011-0127-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Busch E, Kruger K, Hossmann KA. Improved model of thromboembolic stroke and rt-PA induced reperfusion in the rat. Brain Res. 1997;778(1):16–24. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01008-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gerriets T, et al. The macrosphere model: evaluation of a new stroke model for permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. J Neurosci Methods. 2003;122(2):201–211. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(02)00322-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Belayev L, et al. Middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat by intraluminal suture. Neurological and pathological evaluation of an improved model. Stroke. 1996;27(9):1616–1622. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.9.1616. discussion 1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garcia JH, et al. Neurological deficit and extent of neuronal necrosis attributable to middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Statistical validation. Stroke. 1995;26(4):627–634. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.4.627. discussion 635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kawamura S, et al. Reversible middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats using an intraluminal thread technique. Surg Neurol. 1994;41(5):368–373. doi: 10.1016/0090-3019(94)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawamura S, et al. Rat middle cerebral artery occlusion using an intraluminal thread technique. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1991;109(3–4):126–132. doi: 10.1007/BF01403007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Memezawa H, Smith ML, Siesjo BK. Penumbral tissues salvaged by reperfusion following middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Stroke. 1992;23(4):552–559. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.4.552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rink C, et al. Minimally invasive neuroradiologic model of preclinical transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in canines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(37):14100–14105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806678105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ginsberg MD, B R. Small animal models of global and focal cerebral ischemia. In: Ginsberg MD, Bogousslavsky J, editors. Cerebrovascular Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 55.van der Worp HB, et al. Can animal models of disease reliably inform human studies? PLoS Med. 2010;7(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000245. e1000245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lees JS, et al. Stem cell-based therapy for experimental stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Stroke. 2012;7(7):582–588. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2012.00797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Toda H, et al. Grafting neural stem cells improved the impaired spatial recognition in ischemic rats. Neurosci Lett. 2001;316(1):9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02331-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ferrari A, et al. Immature human NT2 cells grafted into mouse brain differentiate into neuronal and glial cell types. FEBS Lett. 2000;486(2):121–125. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02251-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Borlongan CV, et al. Transplantation of cryopreserved human embryonal carcinoma-derived neurons (NT2N cells) promotes functional recovery in ischemic rats. Exp Neurol. 1998;149(2):310–321. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1997.6730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Veizovic T, et al. Resolution of stroke deficits following contralateral grafts of conditionally immortal neuroepithelial stem cells. Stroke. 2001;32(4):1012–1019. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.4.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Modo M, et al. Neurological sequelae and long-term behavioural assessment of rats with transient middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Neurosci Methods. 2000;104(1):99–109. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(00)00329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Englund U, et al. Grafted neural stem cells develop into functional pyramidal neurons and integrate into host cortical circuitry. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(26):17089–17094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252589099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kopen GC, Prockop DJ, Phinney DG. Marrow stromal cells migrate throughout forebrain and cerebellum, and they differentiate into astrocytes after injection into neonatal mouse brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(19):10711–10716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen J, Li Y, Chopp M. Intracerebral transplantation of bone marrow with BDNF after MCAo in rat. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39(5):711–716. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(00)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li Y, et al. Intrastriatal transplantation of bone marrow nonhematopoietic cells improves functional recovery after stroke in adult mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20(9):1311–1319. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200009000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Woodbury D, et al. Adult rat and human bone marrow stromal cells differentiate into neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2000;61(4):364–370. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20000815)61:4<364::AID-JNR2>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Munoz-Elias G, et al. Adult bone marrow stromal cells in the embryonic brain: engraftment, migration, differentiation, and long-term survival. J Neurosci. 2004;24(19):4585–4595. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5060-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Borlongan CV, et al. Central nervous system entry of peripherally injected umbilical cord blood cells is not required for neuroprotection in stroke. Stroke. 2004;35(10):2385–2389. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000141680.49960.d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Eglitis MA, Mezey E. Hematopoietic cells differentiate into both microglia and macroglia in the brains of adult mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(8):4080–4085. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.4080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hess DC, et al. Bone marrow as a source of endothelial cells and NeuN-expressing cells After stroke. Stroke. 2002;33(5):1362–1368. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000014925.09415.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li Y, et al. Treatment of stroke in rat with intracarotid administration of marrow stromal cells. Neurology. 2001;56(12):1666–1672. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.12.1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen J, et al. Intravenous administration of human bone marrow stromal cells induces angiogenesis in the ischemic boundary zone after stroke in rats. Circ Res. 2003;92(6):692–699. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000063425.51108.8D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen J, et al. Intravenous administration of human umbilical cord blood reduces behavioral deficits after stroke in rats. Stroke. 2001;32(11):2682–2688. doi: 10.1161/hs1101.098367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Willing AE, et al. Intravenous versus intrastriatal cord blood administration in a rodent model of stroke. J Neurosci Res. 2003;73(3):296–307. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Riess P, et al. Transplanted neural stem cells survive, differentiate, and improve neurological motor function after experimental traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(4):1043–1052. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200210000-00035. discussion 1052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhao LR, et al. Human bone marrow stem cells exhibit neural phenotypes and ameliorate neurological deficits after grafting into the ischemic brain of rats. Exp Neurol. 2002;174(1):11–20. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2001.7853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Peled A, et al. The chemokine SDF-1 activates the integrins LFA-1, VLA-4, and VLA-5 on immature human CD34(+) cells: role in transendothelial/stromal migration and engraftment of NOD/SCID mice. Blood. 2000;95(11):3289–3296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yamaguchi J, et al. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 effects on ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cell recruitment for ischemic neovascularization. Circulation. 2003;107(9):1322–1328. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000055313.77510.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reyes M, et al. Origin of endothelial progenitors in human postnatal bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(3):337–346. doi: 10.1172/JCI14327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rajantie I, et al. Adult bone marrow-derived cells recruited during angiogenesis comprise precursors for periendothelial vascular mural cells. Blood. 2004;104(7):2084–2086. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mahmood A, Lu D, Chopp M. Intravenous administration of marrow stromal cells (MSCs) increases the expression of growth factors in rat brain after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21(1):33–39. doi: 10.1089/089771504772695922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Recommendations for standards regarding preclinical neuroprotective and restorative drug development. Stroke. 1999;30(12):2752–2758. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.12.2752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fukuda S, del Zoppo GJ. Models of focal cerebral ischemia in the nonhuman primate. ILAR J. 2003;44(2):96–104. doi: 10.1093/ilar.44.2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Neubuerger KT. Lesions of the human brain following circulatory arrest. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1954;13(1):144–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brierley JB, et al. Brain damage in the rhesus monkey resulting from profound arterial hypotension. I. Its nature, distribution and general physiological correlates. Brain Res. 1969;13(1):68–100. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(69)90144-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nemoto EM, et al. Global brain ischemia: a reproducible monkey model. Stroke. 1977;8(5):558–564. doi: 10.1161/01.str.8.5.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wolin LR, Massopust LC, Jr, Taslitz N. Tolerance to arrest of cerebral circulation in the rhesus monkey. Exp Neurol. 1971;30(1):103–115. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(71)90225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pulsinelli WA, Brierley JB, Plum F. Temporal profile of neuronal damage in a model of transient forebrain ischemia. Ann Neurol. 1982;11(5):491–498. doi: 10.1002/ana.410110509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Smith ML, Auer RN, Siesjo BK. The density and distribution of ischemic brain injury in the rat following 2–10 min of forebrain ischemia. Acta Neuropathol. 1984;64(4):319–332. doi: 10.1007/BF00690397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kirino T. Delayed neuronal death in the gerbil hippocampus following ischemia. Brain Res. 1982;239(1):57–69. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(82)90833-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zola-Morgan S, Squire LR, Amaral DG. Human amnesia and the medial temporal region: enduring memory impairment following a bilateral lesion limited to field CA1 of the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1986;6(10):2950–2967. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-10-02950.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rempel-Clower NL, et al. Three cases of enduring memory impairment after bilateral damage limited to the hippocampal formation. J Neurosci. 1996;16(16):5233–5255. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-16-05233.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Petito CK, Lapinski RL. Postischemic alterations in ultrastructural cytochemistry of neuronal Golgi apparatus. Lab Invest. 1986;55(6):696–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fujioka M, et al. Hippocampal damage in the human brain after cardiac arrest. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2000;10(1):2–7. doi: 10.1159/000016018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zola-Morgan S, et al. Enduring memory impairment in monkeys after ischemic damage to the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1992;12(7):2582–2596. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02582.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tabuchi E, et al. Hippocampal neuronal damage after transient forebrain ischemia in monkeys. Brain Res Bull. 1992;29(5):685–690. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(92)90139-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tabuchi E, et al. Ischemic neuronal damage specific to monkey hippocampus: histological investigation. Brain Res Bull. 1995;37(1):73–87. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(94)00262-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Yamashima T. Implication of cysteine proteases calpain, cathepsin and caspase in ischemic neuronal death of primates. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;62(3):273–295. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yamashima T, et al. Inhibition of ischaemic hippocampal neuronal death in primates with cathepsin B inhibitor CA-074: a novel strategy for neuroprotection based on 'calpain-cathepsin hypothesis'. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10(5):1723–1733. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yamashima T, et al. Transient brain ischaemia provokes Ca2+, PIP2 and calpain responses prior to delayed neuronal death in monkeys. Eur J Neurosci. 1996;8(9):1932–1944. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Yamashima T, et al. Sustained calpain activation associated with lysosomal rupture executes necrosis of the postischemic CA1 neurons in primates. Hippocampus. 2003;13(7):791–800. doi: 10.1002/hipo.10127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Frykholm P, et al. Relationship between cerebral blood flow and oxygen metabolism, and extracellular glucose and lactate concentrations during middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion: a microdialysis and positron emission tomography study in nonhuman primates. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(6):1076–1084. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.102.6.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nemoto EM, et al. Hyperthermia and hypermetabolism in focal cerebral ischemia. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2005;566:83–89. doi: 10.1007/0-387-26206-7_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Schmahmann JD, Rosene DL, Pandya DN. Ataxia after pontine stroke: insights from pontocerebellar fibers in monkey. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(4):585–589. doi: 10.1002/ana.20060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Vaitkevicius PV, et al. A cross-link breaker has sustained effects on arterial and ventricular properties in older rhesus monkeys. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(3):1171–1175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Tsukada T, Watanabe M, Yamashima T. Implications of CAD and DNase II in ischemic neuronal necrosis specific for the primate hippocampus. J Neurochem. 2001;79(6):1196–1206. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]