Abstract

The current study examined the longitudinal associations between family ethnic socialization and youths’ ethnic identity among a sample of Mexican-origin youth (N = 178, Mage = 18.17, SD = .46). Findings from multiple-group cross lagged panel models over a two year period indicated that for U.S.-born youth with immigrant parents, the process appeared to be family-driven: Youths’ perceptions of family ethnic socialization in late adolescence were associated with significantly greater ethnic identity exploration and resolution in emerging adulthood, while youths’ ethnic identity during late adolescence did not significantly predict youths’ future perceptions of family ethnic socialization. Conversely, for U.S.-born youth with U.S. born parents, youths’ ethnic identity significantly predicted their future perceptions of family ethnic socialization but perceptions of family ethnic socialization did not predict future levels of youths’ ethnic identity, suggesting a youth-driven process. Findings were consistent for males and females.

Keywords: ethnic identity, family socialization, Latino, Mexican, adolescents, emerging adults

Scholars argue that the family is critical for helping children learn values and behaviors that make it easier for them to adjust to their surrounding environments (Parke & Buriel, 1998). Indeed, for Latino youth, family socialization with respect to ethnicity is critical in the U.S., where Latinos are a numerical ethnic minority and experiences with discrimination can be commonplace (Edwards & Romero, 2008) and have been linked to youth maladjustment (Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007). Existing work has found support for the central role that families play in the process of Latino youths’ ethnic identity development (e.g., Supple, Ghazarian, Frabutt, Plunkett, & Sands, 2006; Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, Bámaca, & Guimond, 2009). Furthermore, based on ecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1989), which argues that development and outcomes are the result of interactions between the individual and his or her environment, studies have examined how adolescent characteristics such as gender and nativity interact with family ethnic socialization to inform youths’ ethnic identity development (e.g.,Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2010). What has not been examined, however, is whether youths’ ethnic identity informs families’ ethnic socialization efforts, or if this process is reciprocal.

From a developmental perspective, socialization is conceived as a largely bidirectional and interactive process whereby parents’ socialization efforts are informed by child characteristics and behaviors (Maccoby, 1992) and both parents and youth are active agents in this process (Kuczynski, 2003). Consistent with García Coll and colleagues’ (1996) recommendations to understand how normative developmental processes unfold among ethnic minority youth, and prior work emphasizing the critical role of families in Latino youths’ ethnic identity (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2009), the current study examined the longitudinal associations between family ethnic socialization and adolescent ethnic identity among a sample of Mexican-origin youth transitioning from late adolescence to emerging adulthood.

Individuals of Mexican origin represent the largest segment (i.e., 63%) of the U.S. Latino population (Ennis, Ríos-Vargas, & Albert, 2011), which is the largest ethnic minority group in the U.S. and is expected to comprise 30% of the U.S. population by 2050 (U.S. Census, 2008). Because ethnic identity has been established as an important predictor of positive outcomes such as self-esteem and academic adjustment among Latino youth (Schwartz, Zamboanga, & Jarvis, 2007; Supple et al., 2006), understanding how this normative developmental process unfolds among this large and rapidly growing group has important implications for their future adaptation and, thus, for the subsequent contributions (e.g., social, economic) this large segment of the population will make to society.

Understanding these processes during the developmental transition of late adolescence to emerging adulthood is important because it captures a period of the lifespan when individuals have the greatest opportunities for identity exploration (Arnett, 2000). In addition, understanding the influence of family socialization efforts during the transition to emerging adulthood is particularly important for Latino youth because research has demonstrated that Latinos in emerging and young adulthood (i.e., aged 18–25 years), relative to their European American counterparts, have a particularly strong commitment to family that guides their values and behaviors (Fuligni, 2007). Finally, socialization is a process that occurs throughout the lifespan and family is considered to be a critical socialization agent throughout different stages of development (Arnett, 1995); thus, understanding how family ethnic socialization and youth ethnic identity inform one another during late adolescence to emerging adulthood will extend previous work, which has focused largely on the developmental period of adolescence.

Family Ethnic Socialization

Family ethnic socialization refers to parents’ and other family members’ efforts to expose youth to the values and behaviors of their ethnic culture1 (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2009). Although conceptualized broadly to include parental and non-parental socialization agents (Knight, Bernal, Garza & Cota, 1993), scholars often emphasize parents’ efforts when discussing family ethnic socialization (e.g., Rivas-Drake, Hughes, & Way, 2009), likely due to the important influence of parents on child socialization (Maccoby, 1992) and also because parents are considered the prime source of information about ethnicity for youth (Hughes et al., 2006; Knight et al., 2011). In the 2000 decade in review of Journal of Marriage and Family, McLoyd, Cauce, Takeuchi, and Wilson reviewed the literature on racial and ethnic socialization in the family and concluded that the knowledge base was large with respect to the content and nature of socialization messages, but there was a very limited understanding of whether racial and ethnic socialization were linked to youths’ development, including their ethnic identity development, and whether socialization varied as a function of youth gender. Since 2000, there has been exponential growth in this literature, and a recent review noted that one of the most consistent findings across studies and among multiple ethnic groups is that parents’ ethnic socialization efforts are positively associated with various aspects of ethnic identity, such as ethnic knowledge and positive attitudes about ethnicity (Hughes et al., 2008). Furthermore, among Latino youth and families specifically, empirical evidence (e.g., Supple et al., 2006; Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2010) supports the notion that family ethnic socialization is positively associated with youths’ ethnic identity exploration (i.e., the degree to which youth have explored their ethnicity) and ethnic identity resolution (i.e., the degree to which they are clear about the meaning that their ethnic group membership has in their lives; Umaña-Taylor, Yazedjian, & Bámaca-Gomez, 2004), although much of this work has been based on cross-sectional data.

Interestingly, much of the empirical work on family ethnic socialization and adolescents’ ethnic identity to date has an implied directional bias suggesting that the associations between family ethnic socialization and youth ethnic identity represent a family-driven process, rather than a youth-driven, or bidirectional process. In extant cross-sectional (e.g., Supple et al., 2006; Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004) and longitudinal (e.g., Knight et al., 2011; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2009; Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2010) work, family ethnic socialization has been examined as a predictor of ethnic identity rather than the reverse. However, theoretical work suggests a different process; in fact, a major tenet of ecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1989) is that human development is the result of an interactive process between an individual and his or her environment. If indeed individuals are influenced by but also influence the environments in which they develop, parents’ ethnic socialization efforts should be informed by youths’ characteristics. Although researchers emphasize the agency that youth have in the process of ethnic identity formation (e.g., Quintana et al., 1999; Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004), existing work has focused almost exclusively on how youth characteristics (e.g., gender) may modify how family ethnic socialization informs ethnic identity (e.g., the strength of the association), not whether youths’ ethnic identity may modify family ethnic socialization efforts.

Family Ethnic Socialization and Ethnic Identity: Examining Contextual Sensitivity

An important limitation of work on minority youth is the lack of attention to intragroup variability. Scholars have underscored the need for work that acknowledges within group diversity (García Coll et al., 1996). Spencer’s (2006) Phenomenological Variant of Ecological Systems Theory (PVEST) is a useful framework for understanding within group variability, as PVEST underscores that cultural contexts can inform individuals’ meaning-making process, how experiences are perceived, and the resulting outcomes. As noted by Spencer, Dupree, and Harmann (1997), individuals’ perceptions of an experience and the cultural context within which that experience is occurring will inform how individuals adapt. With respect to the focus of the current study, an important cultural context that can inform the association between family ethnic socialization and ethnic identity is the immigrant status of the family.

In fact, existing work notes that family ethnic socialization efforts vary as a function of parents’ nativity (e.g., Knight et al., 2011) and youth’s nativity (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2009), with those whose parents have been born in the U.S. or whose families have been in the U.S. for more generations reporting lower levels of ethnic socialization. Although there are no studies to our knowledge that have examined whether the association between family ethnic socialization and ethnic identity varies as a function of nativity, it is possible that nativity could be a moderator of these associations. For example, because Mexico-born youth, compared to their U.S.-born counterparts, have a dual frame of reference (i.e., having first-hand experiences in both Mexico and the U.S.; Suárez-Orozco & Suárez-Orozco, 1995), experiences with ethnic socialization may have a different meaning for their ethnic identity development given their more intimate knowledge and perhaps greater attachment to Mexico. Given the lack of prior research in this area, we explored nativity status as a potential moderator of the association between family ethnic socialization and ethnic identity and did not pose specific hypotheses. Furthermore, we examined nativity status as a family-level construct by taking into account the country of birth of the youth and his or her mother. We used mothers’ nativity, rather than fathers’, given prior work that has noted the robust effect of mothers’ ethnic socialization on adolescent ethnic identity (Rumbaut, 1994; Umaña-Taylor, O’Donnell, Knight, Roosa, Berkel, & Nair, 2012).

In addition to family nativity status, a second contextual factor that is important to examine is adolescent gender. Scholars note more traditional gender role attitudes and socialization practices among Latinos (e.g., Azmitia & Brown, 2002), and particularly with respect to the expectations that females stay close to the family and males have more freedom to explore (e.g., Ramirez & Ontai, 2004). Specific to the relations of interest in the current study, societal expectations regarding females being the carriers of culture (e.g., Phinney, 1990) could lead to females being more likely than males to engage in ethnic-related practices and behaviors as a result of any family ethnic socialization experiences and/or could lead to families perceiving that females are eliciting more ethnic socialization than are males. As such, we hypothesized that the associations between family ethnic socialization and ethnic identity would be significantly stronger for females than males.

The Current Study

The current study tested whether family ethnic socialization informed youths’ ethnic identity (i.e., family-driven process), whether youths’ ethnic identity informed family ethnic socialization efforts (i.e., youth-driven process), or whether family ethnic socialization and youths’ ethnic identity mutually informed one another (i.e., reciprocal process). These associations were examined over a two year period with a specific focus on the developmental components of ethnic identity exploration and ethnic identity resolution. Youth gender and family nativity status were tested as potential moderators of the associations of interest, and family socioeconomic status (SES) was included as a control variable in all analyses, given prior work noting that SES was correlated with families’ nativity status (Updegraff & Umaña-Taylor, 2010).

Method

Participants

Data were from a longitudinal study designed to examine family processes and youth development in Mexican-origin families (Updegraff, Umaña-Taylor, McHale, Wheeler, & Perez-Brena, 2012). Mexican-origin families with a 7th grader (i.e., target adolescent) were recruited from junior high schools in five school districts and from five parochial schools in and around a large southwestern metropolitan area, with the goal of capturing a broad range of socioeconomic status groups. The percent of students receiving free/reduced lunch varied from 8% to 82% across schools. Eligibility requirements included that (a) the target adolescent and at least one older adolescent sibling were living at home, (b) youth were living with biological mothers and biological or long-term adoptive fathers (i.e., fathers in the home for a minimum of 10 years), (c) mothers were of Mexican origin; and (d) fathers were working at least 20 hours/week (given the larger study’s interest in parents’ roles). Although not a study requirement, 93% of fathers also were of Mexican descent.

The larger study consisted of four phases of data collection; the current study focused on data gathered during Phase 3 (i.e., when target adolescents were in 12th grade) and Phase 4 (i.e., two years after Phase 3) because the measures of interest (i.e., ethnic identity and familial ethnic socialization) were only administered at these phases. Families who participated in the latter two waves reflect 72% (n = 178) of the original sample from Phase 1 (N = 246). Non-participating families (n = 68) reported lower income (M = $39,801; SD =$30,849 vs. M = $59,326; SD = $48,542) and lower maternal education (M = 8.99; SD = 3.68 vs. M = 10.85; SD = 3.64) at Phase 1 than participating families.

Among the 178 families included in the current study, families represented a range of socioeconomic levels, with a median annual household income of $67,967 (SD = $51,298; range = $0 to $315,000) at Phase 3. A majority of parents (67.8%) were born outside the U.S. and, at Phase 3, youths’ parents had completed an average of 10.58 years of education (M = 10.85; SD = 3.64 for mothers, and M = 10.31; SD = 4.24 for fathers). The youth sample included 93 females and 85 males, who were 18.17 years old (SD = .46), on average, at Phase 3. A majority of youth (65.7%) were born in the US, with the remainder being born in Mexico. Youth were interviewed in their language of preference, with most (90.8%) choosing to be interviewed in English.

Procedures

At Phases 3 and 4, youth participated in individual in-home interviews, in which bilingual interviewers read all questions aloud and entered responses into laptops. Families received $125 for participation in in-home interviews at Phase 3. At Phase 4, participant incentives were distributed to individuals, rather than given in a lump sum to the family, and each participating family member received $75. All materials were translated into Spanish and back translated into English by separate individuals. Final translations were reviewed by a third translator who was of Mexican origin and discrepancies were resolved by the research team.

Measures

Parents’ reports on their own country of birth, and mothers’ reports of youth’s country of birth were collected at Phase 1. In addition, family SES was calculated by standardizing maternal and paternal educational attainment and family income based on Phase 1 assessments. The measures of ethnic identity and familial ethnic socialization, described below, were administered to youth and collected only at Phase 3 and Phase 4.

Family Ethnic Socialization

The Familial Ethnic Socialization Measure (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004) was used to assess the degree to which youth perceived that their families socialized them with respect to their Mexican culture. Twelve items (e.g., “My family teaches me about our family’s ethnic/cultural background”) were scored on a 5-point Likert scale, with end points of not at all (1) and very much (5). Higher scores indicated higher levels of familial ethnic socialization. The measure has demonstrated adequate reliability and support for its validity in prior work with Latino youth (e.g., Supple et al., 2006; Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, Bámaca, & Guimond, 2009). In this study, Cronbach’s alphas were .93 and .91 at Phase 3 and 4, respectively.

Ethnic Identity

Youths’ ethnic identity was assessed using the exploration and resolution items from the Ethnic Identity Scale (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004), which has demonstrated adequate reliability and evidence of construct validity in prior work (e.g., Supple et al., 2006; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2009). Items were scored on a 4-point Likert scale with response categories ranging from does not describe me at all (1) to describes me very well (4). Sample items include, “I have attended events that have helped me learn more about my ethnicity” (exploration, 7 items), and “I have a clear sense of what my ethnicity means to me” (resolution, 4 items). Higher scores reflect greater degrees of exploration and resolution of ethnic identity. In this study, a composite ethnic identity score was created using the mean across items. Cronbach’s alphas for the composite scale were .89 and .84 at Phase 3 and 4, respectively.

Results

Analytic Approach

To examine the relations between family ethnic socialization (FES) and adolescents’ ethnic identity (EI) at two time points, an autoregressive cross-lag panel model (Cole & Maxwell, 2003) was conducted in Mplus 6.0 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2007). Specifically, the model included two stability paths: a path from Phase 3 FES to Phase 4 FES, and a path from Phase 3 adolescent EI to Phase 4 adolescent EI. In addition to the stability paths, the model included a path from Phase 3 FES to Phase 4 adolescent EI, and a path from Phase 3 adolescent EI to Phase 4 FES (i.e., cross-lag paths). SES and adolescent gender were included as controls in all analyses. Also, correlations between exogenous variables (i.e., Phase 3 FES and Phase 3 EI, SES, and gender) and correlations between error terms of endogenous variables were estimated.

In addition to the above analyses, the relations of interest were examined with attention to potential moderation by gender and family nativity status. This was done by conducting two separate multiple group analyses with gender and family nativity status, respectively, as the grouping variable. Gender was coded as a dichotomous variable (i.e., 0 = male, 1 = female). For family nativity status, adolescents were grouped in three different categories: U.S.-born families (n = 67), Mexico-born families (n = 24), and mixed-nativity families (n = 86). Based on prior research noting that a critical age of immigration for youth and parents is age 6 and age 12, respectively (Rumbaut, 1997; Stevens, 1999), we categorized families as U.S.-born families when adolescents were born in the U.S. or born in Mexico but immigrated to the U.S by the age of 6 years and mothers were born in the US or born in Mexico but immigrated to the U.S. by the age of 12 years. Mexico-born families included adolescents who were born in Mexico and immigrated to the U.S. after age 6 and mothers who were born in Mexico and immigrated to the U.S. after age 12. Mixed-nativity families included adolescents who were born in the U.S. or immigrated before age 6 and mothers who were born in Mexico and immigrated after age 12. In one family, the mother was born in the U.S. and the adolescent was born in Mexico; this family could not be classified into a family nativity status group and was therefore excluded from the family nativity status moderation analysis. For families where mothers’ and fathers’ nativity status was different (n = 20), families were reclassified using fathers’ nativity and all study models were retested. Because results were consistent, categorization using mothers’ nativity status are presented.

For all multiple group analyses, a fully unconstrained model was tested, followed by a model in which paths from FES P3 to EI P4 and EI P3 to FES P4 were constrained to be equal across groups. A significant chi-square statistic, indicating that there was moderation by the grouping variable of interest (i.e., the path was significantly different across groups; Kline, 1998), was then followed up by an individual test of each path to determine whether freeing the individual path across groups demonstrated an improvement in model fit when compared to the fully constrained model.

Missing data were handled using Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML). Auxiliary variables, or variables that are potential correlates of the variables of interest and of missingness, were incorporated into the analysis (Enders, 2010). The inclusion of auxiliary variables can reduce bias attributed to missingness and increase power. As such, Phase 1 mother and father familism values were modeled as auxiliary variables in all models. Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics by nativity status group are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Correlations, Means and Standard Deviations among Study Variables by Family Nativity Status

| U.S.-born Families (n=67)

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | Mean | SD | |

|

|

|||||||

| 1. FES (P3) | -- | 3.15 | .95 | ||||

| 2. FES (P4) | .78*** | -- | 3.16 | .86 | |||

| 3. EI (P3) | .71*** | .72*** | -- | 2.77 | .63 | ||

| 4. EI (P4) | .59*** | .77*** | .72*** | -- | 2.79 | .53 | |

| 5. Family SES | .19 | .39** | .16 | .23† | -- | 0.70 | .57 |

| 6. Adolescent gender | .28* | .23† | .45*** | .13 | .19 | 0.55 | .50 |

|

| |||||||

| Mexico-born Families (n = 24) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Mean | SD | |

|

|

|||||||

| 1. FES (P3) | -- | 3.59 | .93 | ||||

| 2. FES (P4) | .70** | -- | 3.43 | .76 | |||

| 3. EI (P3) | .06 | −.30 | -- | 2.85 | .63 | ||

| 4. EI (P4) | .39 | .54* | .25 | -- | 2.94 | .56 | |

| 5. Family SES | −.19 | −.01 | .01 | .14 | -- | −0.55 | .77 |

| 6. Adolescent gender | −.09 | −.04 | .30 | −.05 | −.19 | 0.54 | .51 |

|

| |||||||

| Mixed-nativity Families (n = 86) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | Mean | SD | |

|

|

|||||||

| 1. FES (P3) | -- | 3.73 | .72 | ||||

| 2. FES (P4) | .60*** | -- | 3.67 | .71 | |||

| 3. EI (P3) | .34** | .14 | -- | 2.87 | .68 | ||

| 4. EI (P4) | .66*** | .63*** | .34** | -- | 3.09 | .49 | |

| 5. Family SES | −.06 | .04 | .01 | −.07 | -- | −0.11 | .68 |

| 6. Adolescent gender | .24* | .16 | .07 | .09 | −.13 | 0.48 | .50 |

Note. FES = Family ethnic socialization; EI = Ethnic identity. P3 = Phase 3; P4 = Phase 4.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001. Based on missing data, correlation sample sizes differed from cell to cell. Samples ranged from 43 to 67 for U.S.-born families, 14 to 24 for Mexico-born families and 61 to 86 for mixed-nativity families. For cross-lag models, the full samples sizes were used.

Examination of Ethnic Identity and FES Cross-Lagged Model

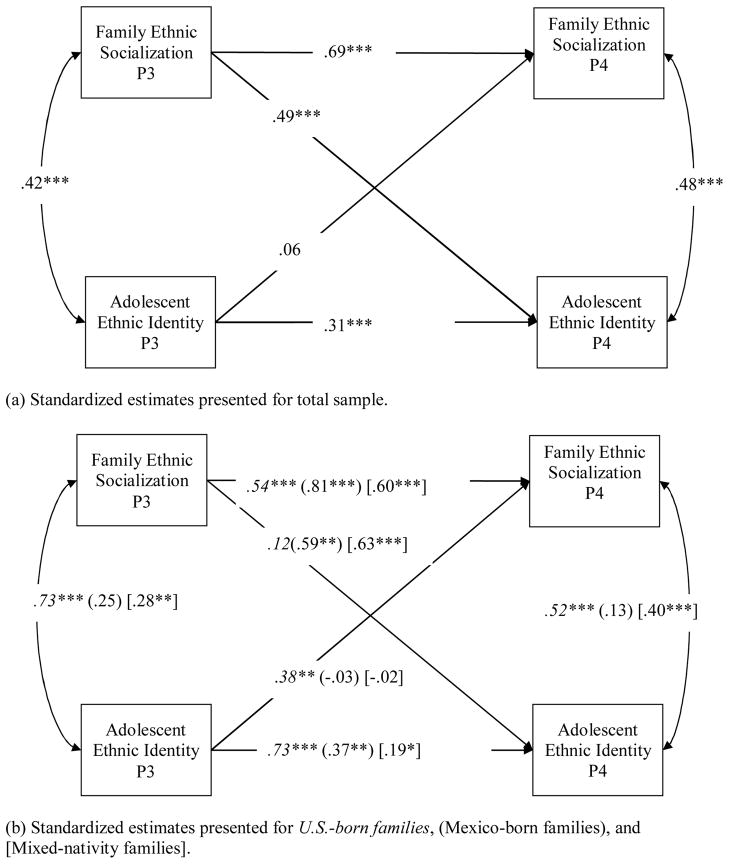

Cross-lag associations between FES and EI (see Figure 1a) revealed high rank-order stability in FES between Phase 3 and Phase 4 [β = .69 (SE = .06), p < .001] and moderate rank-order stability in EI between Phase 3 and Phase 4 [β = .31 (SE = .07), p < .001]. Results also revealed a significant path from Phase 3 FES to Phase 4 EI [β = .49 (SE = .07), p < .001], suggesting that higher FES at Phase 3 predicted higher adolescent EI at Phase 4. The path between Phase 3 adolescent EI and Phase 4 FES was not significant.

Figure 1.

Standardized estimates of cross-lag model testing family ethnic socialization and adolescent ethnic identity for (a) the total sample (N = 178) and (b) family nativity status groups (N = 177). P3 = Phase 3; P4 = Phase 4.* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001. Family SES and adolescent gender were added in as controls on FES P4 and adolescent ethnic identity P4.

The multi-group analyses revealed no difference by gender [χ2Δ (2) = .86, p = .65]. Next, we tested the multi-group model with family nativity status as the grouping variable and included adolescent gender as a control variable. Differences by family nativity status, however, did emerge [χ2Δ (4) = 14.44, p < .01]. As seen in Figure 1b, for youth in U.S.-born families, the relation between Phase 3 FES and Phase 4 EI was not significant. However, for youth in Mexico-born and mixed-nativity status families the path was significant [β = .59 (SE = .18), p < .01; β = .63 (SE = .08), p < .001, respectively], suggesting that higher FES at Phase 3 predicted higher levels of EI at Phase 4. A chi-square difference test revealed that the path estimate for youth in U.S.-born families was significantly different from the path estimate for youth in mixed-nativity families [χ2Δ (1) = 11.52, p < .001] and was marginally significantly different from the path estimate for youth in Mexico-born families [χ2Δ (1) = 3.54, p = .06]. Path estimates did not differ between Mexico-born families and mixed-nativity status families [χ2Δ (1) = .38, p = .54]. In contrast, only youth in U.S.-born families reported a significant relation between Phase 3 EI and Phase 4 FES [β = .38 (SE = .13), p < .01]. A chi-square difference test revealed that the path estimate for youth in U.S.-born families was significantly different from the estimate for youth in mixed-nativity status families [χ2Δ (1) = 6.31, p < .05] and was marginally significantly different from the estimate for youth in Mexico-born families [χ2Δ (1) = 3.43, p = .06]. Path estimates did not differ between youth in Mexico-born families and those in mixed-nativity status families [χ2Δ (1) = .01, p = .96].

Discussion

Our study examined the processes by which family ethnic socialization efforts and youths’ ethnic identity development informed one another during the transition from late adolescence into emerging adulthood, contributing to a growing body of work on the developmental processes that are central to ethnic minority youth. These findings provided compelling evidence that the direction of effect between family ethnic socialization efforts and youths’ ethnic identity formation may be largely determined by the immigrant status of the family. Indeed, scholars have argued that culture, ethnicity, and the intragroup variability that exists within ethnic minority populations must be at the core of theoretical formulations that drive our understanding of child development (García Coll et al., 1996). Our findings underscore the importance of such a recommendation.

Family Ethnic Socialization and Ethnic Identity: A Context-Sensitive Process?

Identity formation is a normative developmental task of adolescence (Erikson, 1968) and scholars note that, for ethnic minority youth, ethnic identity formation is an important developmental task (e.g., French, Seidman, Allen, & Aber, 2006; Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen, & Guimond, 2009). Because ethnic identity has been positively associated with self-esteem and academic adjustment among Latino youth (e.g., Supple et al., 2006; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004) and has been linked to positive attitudes toward and relations with members of other ethnic and racial groups (Phinney, Jacoby, & Silva, 2007), understanding how ethnic identity develops and the factors that inform a strong ethnic identity has been a key focus of research in the past decade. Among this research with Latino youth, scholars have identified the family as a central force that informs the ethnic identity development process (Knight et al., 1993; Supple et al., 2006; Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, et al., 2009). In the current study we found that, indeed, for youth with Mexico-born mothers, adolescents’ reports of family ethnic socialization efforts predicted higher youth ethnic identity two years later.

Rumbaut’s (1994) early work examining immigrant youths’ self-identification labels drew a similar conclusion stating that “The children’s ethnic self-identities strongly tend to mirror the perceptions of their parents’ (and especially their mother’s) own ethnic self-identities, as if they were reflections in an ethnic looking-glass.” (p. 790). Rumbaut went on to suggest that family was the crucible of the ethnic socialization process among children of immigrants. Although Rumbaut’s analysis was based exclusively on ethnic identification labels (e.g., Mexican v. Mexican-American v. Hispanic v. American), our work suggests that this argument holds for the developmental processes of ethnic identity exploration and resolution, and the role of family ethnic socialization in these critical normative developmental processes. An important emphasis in this conclusion, however, is that this association appears to be context-specific, as it was only the case for youth with foreign-born mothers (i.e., children of immigrants, which defined the Mexico-born and mixed-nativity status groups in the current study), but not when parents and youth were U.S. born.

The pattern that emerged in the current study among U.S.-born youth with U.S.-born mothers suggested that it was youths’ ethnic identity during late adolescence that predicted higher family ethnic socialization during the transition to emerging adulthood, while evidence for the reverse did not emerge in this group. This suggests that in families where there is a more extensive generational history in the U.S. (i.e., longer history of U.S.-born generations), youth may be driving this process, which is consistent with theoretical work on ethnic identity that argues for the agency that youth have in the process of ethnic identity formation (e.g., Quintana, 1998). Our findings are particularly important, however, because in prior work Hughes and colleagues (2008) explored African American, Latino, Chinese, and European American parents’ motivations for engaging in ethnic socialization (i.e., referred to as cultural socialization in their study) and noted that Chinese and Latino parents’ ethnic socialization efforts, in particular, appeared to be driven largely by their own motivations to pass on values and help children know about their history, and there was little evidence to suggest that youth were driving this aspect of ethnic socialization. Although Hughes and colleagues’ findings could appear contradictory to the theoretical literature that emphasizes youths’ agency, the current study’s more nuanced examination of within-group variability among Mexican-origin families suggests that the degree to which youths’ agency is evident may vary significantly based on the generational status of the family, with youth agency being clearer when families have been in the U.S. for more generations. Indeed, Hughes and colleagues noted that many of the Chinese and Latino families in their study represented first generation immigrants to the U.S.; thus, their findings may be reflecting the process among a specific demographic subgroup.

Consistent with both Rumbaut’s (1994) and Hughes and colleagues’ (2008) work, our findings for families with foreign-born mothers suggest that the process by which family ethnic socialization and youths’ ethnic identity inform one another over time appeared to be largely driven by youth’s perceptions of family socialization efforts and less by youths’ agency. Immigrant parents may be relatively less focused on cues from their children when it comes to ethnic socialization because of a greater personal investment in preserving their cultural heritage and passing this on to the next generation. This socialization goal may be more prominent or salient in immigrant families than in families with U.S.-born parents because of the dual frame of reference (Suarez-Orozco & Suarez-Orozco, 1995) that foreign-born parents have: they feel a connection to their own place of birth and they understand that their U.S.-born children do not have that same connection. U.S.-born parents do not have this dual frame of reference, as they share the same country of birth with their children.

It also is important to consider that immigrant families may not necessarily be making a conscious choice to preserve their cultural heritage, but rather they are simply doing what is most familiar, comfortable, and perhaps instinctive to them. This may also help to explain why in families with U.S. born parents, youth appear to be driving the process, as U.S.-born parents are likewise doing what is most instinctive and familiar to them, which may not involve an emphasis on the ethnic group because the family is further removed from the immigrant generation. Thus, among U.S. born parents, ethnic socialization efforts may reflect more of a reactive process whereby parents engage in ethnic socialization when they perceive cues of interest from their children (Hughes et al., 2008). Youth may initiate the process out of normative engagement in identity exploration or a social categorization experience outside the home, for example. Importantly, in discussing parent-child relationships in immigrant families, scholars sometimes raise concerns regarding role-reversal in which youth take on parental roles and play a significant role in managing their parents’ lives, given youths’ relatively greater facility with the mainstream language and their parents’ dependence on them for negotiating important social and formal (e.g., educational) settings (e.g., Oznobishin & Kurman, 2009; Parke et al., 2003). Interestingly, our findings illustrate that the process of ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development may represent an instance in which foreign-born parents may retain significant power in parent-child socialization processes.

In sum, many scholars have argued that youth play an active role in the process of forming their ethnic identity (e.g., Knight et al., 1993; Quintana & Vera, 1999; Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004). Generally, theorists posit that as youth mature, these maturations are accompanied by theoretically expected shifts in the ways in which they process information about ethnicity and the way in which this information informs their ethnic identity. To date, these conceptual arguments have been based largely on the agency that youth exhibit as a function of their social and cognitive maturity, and there has been little discussion of the notion that sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., foreign-born versus U.S.-born youth) can introduce variability into how and/or when youths’ agency emerges in this process. Our findings suggest that the association between family ethnic socialization and ethnic identity is context sensitive, with family nativity status being a critical factor that must be considered when determining the stages at which youth and parent forces are most pronounced in this process. It is worthy of note that if we had not examined family nativity status as a moderator in the current study, the conclusions drawn from our research would have erroneously conveyed that this process was driven exclusively by parents’ ethnic socialization efforts and that there was no evidence of youth agency in the links between family ethnic socialization and ethnic identity formation.

Contrary to our expectations, we did not find variability by adolescent gender in the processes examined. The developmental period of interest studied may have played a role in this, given that the prior work in which gender differences have emerged has focused on Latinos transitioning from middle to late adolescence (Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2010). Indeed, the gender intensification hypothesis suggests that youth experience increased socialization pressures to conform to traditional gender roles during adolescence (Hill & Lynch, 1983). Thus, it is possible that as youth transition out of adolescence and into emerging adulthood, pressures to conform to traditional gender roles are less salient. Our hypothesis for gender differences was based on the notion that women would be more strongly influenced by ethnic socialization efforts because of the gendered expectation for women to be the carriers of culture. The findings, however, suggest that the young men and women in this study reacted similarly to ethnic socialization efforts by their families during this developmental transition.

Strengths, Limitations, and Directions for Future Research

Consistent with García Coll and colleagues’ (1996) recommendation to understand processes when studying ethnic minority youths’ normative development, rather than focusing exclusively on outcomes, the current study adds to the field’s understanding of how family ethnic socialization and ethnic identity inform one another during the transition from adolescence into emerging adulthood. In addition, these findings underscore the importance of considering intragroup variability in how this process unfolds over time. Furthermore, to our knowledge, this is the first study to test these developmental processes among young adults who do not represent a convenience sample of university students. Much of the existing longitudinal research focused on Latinos’ ethnic identity and familial ethnic socialization during these developmental periods is based on adolescent samples (e.g., Knight et al., 2011; Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2010) studied exclusively during the developmental period of adolescence, or on convenience samples of emerging adults enrolled in universities (i.e., Syed, Azmitia, & Phinney, 2007). Although understanding these processes among Latino college students is important and advances the field, the generalizability of findings based on college student samples is limited because Latinos are much less likely to attend college than the general U.S. population and, Mexican-origin Latinos specifically represent the lowest levels of high school completion and college attainment among all Latino groups (Ramirez, 2004). Thus, by following a sample of Mexican-origin youth who were recruited into a larger study during early adolescence, the current study likely captures a more representative segment of the emerging adult Mexican-origin population.

Nevertheless, the study is not without limitations and these limitations help to identify important avenues for future research. For instance, the current study was limited to the developmental periods of late adolescence and emerging adulthood; future research will benefit from a longer-term examination of how these processes unfold over time. As noted by Parke and colleagues (2003), there are developmental shifts in the determinants of parent versus child agency throughout development. With respect to ethnic identity and ethnic socialization, it will be important to understand whether this is indeed the case (i.e., developmental periods drive the extent of agency) or if the more salient determinant of parent versus child agency with respect to these processes is family nativity status. For example, it is possible that regardless of developmental stage, family ethnic socialization efforts may always emerge as a reactive form of socialization in reference to an issue being raised by the child among U.S.-born families (e.g., child asking about differences in skin color or language during childhood; adolescent raising concerns about prejudice and discrimination during adolescence; young adult questioning issues of affirmative action during emerging adulthood). This is an empirical question and one that can only be answered by implementing a longer-term longitudinal study in which parents and youth are studied over an extended period of time that captures multiple developmental periods.

In addition, the current study focused exclusively on family ethnic socialization and youth ethnic identity, but it will be informative to understand how distinct features of family members’ cultural orientation, such as parents’ ethnic identity, may add further contextual sensitivity to understanding how this process unfolds. Prior work has identified Mexican American parents’ endorsement of traditional cultural values as a significant concurrent predictor of their socialization efforts (Knight et al., 2011), it will be useful to understand the degree to which parents’ ethnic identity and cultural values inform their future socialization efforts and adolescents’ ethnic identity, as well as examine the directional links among these constructs.

It also is important to note that the current findings are based on adolescents’ perspectives of family ethnic socialization. Although PVEST emphasizes the importance of individuals’ perceptions for driving behavior (Spencer, 2006), future studies should examine whether the current findings are replicated when other family members’ perceptions of adolescents’ family ethnic socialization experiences are examined. In addition, future studies should oversample foreign-born youth and their parents. It is possible, for example, that we were unable to detect significant differences between U.S.-born and Mexico-born families because of the small sample size for the Mexico-born group (n = 24). Indeed, the marginal differences that emerged between these groups may have been due to limited statistical power. Alternative methods of recruitment may be necessary, as Mexico-born youth and their families may be relatively more focused on adapting to the new cultural context of the U.S., including learning how to navigate their schools, communities, and neighborhoods; and these experiences may make them less likely to want to engage in research efforts. Given that immigration from Mexico to the U.S. is continuing at a rapid rate (Grieco et al., 2012), and that 38% of the Mexico-born population is under the age of 18 (Office of Minority Health, 2012), there is a need for a broader knowledge base of the normative developmental experiences of this population of youth, particularly with respect to a construct such as ethnic identity, which has been lauded as an important cultural resource that may buffer the negative effects of stress among ethnic minority populations (Neblett, Rivas-Drake, & Umaña-Taylor, 2012).

In closing, the current study carries many strengths, including its longitudinal design and the examination of ethnic identity and family ethnic socialization across the developmental periods of late adolescence and emerging adulthood. Because ethnic identity can minimize the negative impact of stress and has clear benefits for youth (Neblett et al., 2012), the findings have important implications for practitioners who serve them. Understanding how this process unfolds and, particularly, the family’s role in this process is critical for prevention efforts and practice with families and youth who represent this demographic segment of the U.S.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the families and youth who participated in this project, and to the following schools and districts who collaborated: Osborn, Mesa, and Gilbert school districts, Willis Junior High School, Supai and Ingleside Middle Schools, St. Catherine of Sienna, St. Gregory, St. Francis Xavier, St. Mary-Basha, and St. John Bosco. We thank Mark Roosa, Nancy Gonzales, Roger Millsap, Jennifer Kennedy, Leticia Gelhard, Faith Dunbar-Wagner, Melissa Delgado, Devon Hageman, Lilly Shanahan, Shawna Thayer, Lorey Wheeler, Sarah Killoren, Emily Cansler, Norma Perez-Brena, Sue Annie Rodriguez, Allison Groenendyk, & Anna Soli for their assistance in conducting this investigation. Funding was provided by NICHD grant R01HD39666 (Kimberly Updegraff, Principal Investigator, Adriana Umana-Taylor, Susan M. McHale and Ann C. Crouter, co-principal investigators, Wayne Osgood, co-investigator) and the Cowden Fund to the School of Social and Family Dynamics at ASU.

Footnotes

This concept also has been referred to as cultural socialization in the racial and ethnic socialization literature to distinguish it from other types of socialization such as preparation for bias, which focuses more on families’ efforts to increase awareness of discrimination and prepare youth to cope with these experiences (Hughes, Rodriguez, Smith, Johnson, Stevenson, & Spicer, 2006). We use the term family ethnic socialization in the current study, given that most of the work with Latino youth uses this terminology.

References

- Arnett JJ. Broad and narrow socialization: The family in the context of a cultural theory. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1995;57:617–628. doi: 10.2307/353917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia A, Brown JR. Latino immigrant parents’ beliefs about the “path of life” of their adolescent children. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States. Westport, CT: Praeger Press; 2002. pp. 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecological systems theory. Annals of Child Development. 1989;6:187–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558–577. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LM, Romero AJ. Coping with discrimination among Mexican descent adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2008;30:24–39. doi: 10.1177/0739986307311431. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied Missing Data Analysis. New York, NY: Guilford; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Ríos-Vargas M, Albert NG. 2010 Census Briefs. Washington, D.C: U.S. Census Bureau; 2011. The Hispanic Population: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- French SE, Seidman E, Allen L, Aber JL. The development of ethnic identity during adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(1):1–10. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuligni AJ. Family obligation, college enrollment, and emerging adulthood in Asian and Latin American families. Child Development Perspectives. 2007;1:96–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00022.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- García Coll CG, Crnic K, Lamberty G, Wasik BH, Jenkins R, García HV, McAdoo HP. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67:1891–1914. doi: 10.2307/1131600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco EM, Acosta YD, de la Cruz GP, Gambino C, Gryn T, Larsen LJ, et al. American Community Survey Reports. Washington, D.C: U.S. Census Bureau Population Division; 2012. The Foreign-born Population in the United States: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hill JP, Lynch ME. The intensification of gender-related role expectations during early adolescence. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Petersen A, editors. Girls at puberty: Biological and psychosocial perspectives. New York: Plenum; 1983. pp. 201–228. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, Spicer P. Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42(5):747–770. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rivas D, Foust M, Hagelskamp C, Gersick S, Way N. How to catch a moonbeam: A mixed-methods approach to understanding ethnic socialization processes in ethnically diverse families. In: Quintana SM, McKown C, editors. Handbook of Race, Racism, and the Developing Child. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. pp. 226–277. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York, NY: Guilford; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Berkel C, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales NA, Ettekal I, Jaconis M, Boyd BM. The Socialization of Culturally Related Values in Mexican American Families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73:913–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00856.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Bernal ME, Garza CA, Cota MK. A social cognitive model of the development of ethnic identity and ethnically based behaviors. In: Bernal ME, Knight GP, editors. Ethnic Identity: Formation and Transmission among Hispanics and other Minorities. Albany, NY: SUNY Press; 1993. pp. 213–234. [Google Scholar]

- Kuczynski L. Beyond bidirectionality: Bilateral conceptual frameworks for understanding dynamics in parent-child relations. In: Kuczynski L, editor. Handbook of Dynamics in Parent-Child Relations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE. The role of parents in the socialization of children: An historical overview. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:1006–1017. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.28.6.1006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Cauce AM, Takeuchi D, Wilson L. Marital processes and parental socialization in families of color: A decade review of research. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1070–1093. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01070.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén B. Version 4.1 Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2007. [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr, Rivas-Drake D, Umaña-Taylor AJ. The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6:295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00239.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Office of Minority Health. Hispanic/Latino Profile. 2012 Retrieved June 1, 2012 from http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/templates/browse.aspx?lvl=2&lvlid=54.

- Oznobishin O, Kurman J. Parent-child role reversal and psychological adjustment among immigrant youth in Israel. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:405–415. doi: 10.1037/a0015811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Buriel R. Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In: Damon W, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development. 3. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 463–552. [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, Killian CM, Dennis J, Flyr ML, McDowell DJ, Simpkins S, Kim M, Wild M. Managing the external environment: The parent and child as active agents in the system. In: Kuczynski L, editor. Handbook of Dynamics in Parent-Child Relations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. pp. 247–269. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: Review of Research. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:499–514. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.108.3.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Jacoby B, Silva C. Positive intergroup attitudes: The role of ethnic identity. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2007;31:478–490. doi: 10.1177/0165025407081466. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM. Children’s developmental understanding of ethnicity and race. Applied & Preventive Psychology. 1998;7:27–45. doi: 10.1016/S0962-1849(98)80020-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM, Castañeda-English P, Ybarra VC. Role of perspective-taking abilities and ethnic socialization in development of adolescent ethnic identity. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1999;9:161–184. doi: 10.1207/s15327795jra0902_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM, Vera EM. Mexican American children’s ethnic identity, understanding of ethnic prejudice, and parental ethnic socialization. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1999;21:387–404. doi: 10.1177/0739986399214001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Ontai LL. Gender socialization in Latino/a families: Results from two retrospective studies. Sex Roles. 2004;50:287–299. doi: 10.1023/B:SERS.0000018886.58945.06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez RR. Census 2000 Special Reports. U.S. Washington, D.C: U.S. Census Bureau Department of Commerce; 2004. We the people: Hispanics in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG. The crucible within: Ethnic identity, self-esteem, and segmented assimilation among children of immigrants. International Migration Review. 1994;28:748–794. doi: 10.2307/2547157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut RG. Ties that bind: Immigration and immigrant families in the United States. In: Booth A, Crouter AC, Landale NS, editors. International Migration and Family Change. New York, NY: Lawrence Earlbaum; 1997. pp. 3–46. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Jarvis LH. Ethnic identity and acculturation in Hispanic early adolescents: Mediated relationships to academic grades, prosocial behaviors, and externalizing symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:364–373. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB. Phenomenology and ecological systems theory: Development of diverse groups. In: Damon W, Lerner R, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology. 6. NY: Wiley; 2006. pp. 829–893. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer MB, Dupree D, Hartmann T. A Phenomenological Variant of Ecological Systems Theory (PVEST): A self-organization perspective in context. Development and Psychopathology. 1997;9:817–833. doi: 10.1017/S0954579497001454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Orozco C, Suárez-Orozco M. Transformations: Immigration, family life, and achievement motivation among Latino adolescents. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Supple AJ, Ghazarian SR, Frabutt JM, Plunkett SW, Sands T. Contextual influences on Latino adolescent ethnic identity and academic outcomes. Child Development. 2006;77:1427–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens G. Age at immigration and second language proficiency among foreign-born adults. Language in Society. 1999;28:555–578. doi: 10.1017/S0047404599004030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, Azmitia M, Phinney JS. Stability and change in ethnic identity among Latino emerging adults in two contexts. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2007;7:155–178. doi: 10.1080/15283480701326117. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Alfaro EC, Bámaca MY, Guimond AB. The central role of family socialization in Latino adolescents’ cultural orientation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71:46–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00579.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Fine MA. Examining a model of ethnic identity development among Mexican-origin adolescents living in the U.S. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2004;26:36–59. doi: 10.1177/0739986303262143. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales-Backen MA, Guimond A. Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity: Is there a developmental progression and does growth in ethnic identity predict growth in self-esteem? Child Development. 2009;80:391–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Guimond A. A Longitudinal Examination of Parenting Behaviors and Perceived Discrimination Predicting Latino Adolescents’ Ethnic Identity. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:636–650. doi: 10.1037/a0019376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, O’Donnell M, Knight GP, Roosa MW, Berkel C, Nair R. Ethnic socialization, ethnic identity, and Mexican-origin adolescents’ psychosocial functioning: Examining the moderating role of school ethnic composition. 2012 doi: 10.1177/0011000013477903. Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff K. Latino adolescents’ mental health: Exploring the role of discrimination, ethnic identity, acculturation, and self-esteem. Journal of Adolescence. 2007;30:549–567. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Yazedjian A, Bámaca-Gómez MY. Developing the Ethnic Identity Scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research. 2004;4:9–38. doi: 10.1177/0265407506064214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, Umaña-Taylor AJ. Structure and process in Mexican-origin families and their implications for youth development. In: Lansdale NS, McHale SM, Booth A, editors. Growing up Hispanic: Health and Development of Children of Immigrants. Washington, D.C: Urban Institute; 2010. pp. 97–143. [Google Scholar]

- Updegraff KA, Umaña-Taylor AJ, McHale S, Wheeler LA, Perez-Brena N. Mexican-origin adolescents’ cultural orientations and adjustment: Changes from early to late adolescence. Child Development. 2012;83:1655–1671. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01800.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census. An Older and More Diverse Nation by Midcentury. US Census Brief, CB08-123. 2008 released August 14, 2008 Retrieved March 5, 2012, from http://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/population/cb08-123.