Abstract

Mouse retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) have been classified into around 20 subtypes based on the shape, size, and laminar position of their dendritic arbors. In most cases tested, RGC subtypes classified in this manner also have distinct functional signatures. Here we asked whether RGC subtypes defined by dendritic morphology have stereotyped axonal arbors in their main central target, the superior colliculus (SC). We used transgenic and viral methods to sparsely label RGCs and characterized both dendritic and axonal arbors of individual RGCs. Axon arbors varied in size, shape, and laminar position. For each of 12 subtypes defined dendritically, however, axonal arbors in the contralateral SC showed considerable stereotypy. We found no systematic relationship between the laminar position of an RGC's dendrites within the inner plexiform layer and that of its axon within the retinorecipient zone of the SC, suggesting that distinct developmental mechanisms specify dendritic and axonal laminar positions. We did, however, note a significant correlation between the dendritic field sizes of RGCs and the laminar position of their axon arbors: RGCs with larger dendritic areas, and hence larger receptive fields, projected to deeper strata within the SC. Finally, combining these new results with previous physiological analyses, we find that RGC subtypes that share similar functional properties, such as directional selectivity, project to similar depths within the SC.

Indexing Terms: transgenic mice, lamination, adeno-associated virus, direction selectivity

Many of Cajal's histological studies were based on his conviction that the structure of a neuron provides clues to its function. Retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) provide strong support for his contention. RGC dendrites receive synapses from retinal interneurons (amacrine and bipolar cells) in the inner plexiform layer and send axons to several retinorecipient structures in the brain, of which the superior colliculus (SC) / optic tectum and dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN) are the major targets. Approximately 20 RGC subtypes have been identified on the basis of their dendritic morphology (Rockhill et al., 2002; Dacey et al., 2003; Field and Chichilnisky, 2007; Vögyi et al., 2009) and subtypes with distinct structures have generally been found to have distinct functional signatures (Famiglietti and Kolb, 1976; Masland, 2001; Kim et al., 2008).

In large part, the correspondence of structure with function reflects the fact that the visual features to which RGCs are tuned are determined by the interneurons from which they receive information, and these patterns of connectivity depend on dendritic morphology. Specific subsets of interneurons connect with specific RGCs in one or two of at least 10 sublaminae within the inner plexiform layer (IPL; Roska and Werblin, 2001). Moreover, the region of the visual world that each RGC samples (its receptive field center) is directly related to the extent of its dendritic arbor, which in turn determines the distribution of bipolar cell inputs that it receives (Boycott and Wässle, 1974). In one direction-selective RGC subtype in mouse, a systematic structural asymmetry of the dendritic field is directly related to the direction of motion it prefers (Kim et al., 2008).

Several studies have also shown a clear relationship between the axonal arbors of RGC subtypes and their functions. In primates, for example, three sets of sublaminae in the dLGN primarily receive inputs from distinct groups of RGCs: parasol, midget, and bistratified RGCs project to anatomically segregated regions of the dLGN that define the magno-, parvo-, and koniocellular layers, respectively (Dacey, 2000; Nassi and Callaway, 2009). Similarly, anatomical segregation of axon arbors is seen in nonmammalian vertebrates such as birds and fish, where distinct RGC subsets arborize in specific sublaminae of the optic tectum (Karten et al., 1982; Yamagata and Sanes, 1995; Yamagata et al., 2006; Xiao and Baier, 2007).

In contrast, little is known about the axonal arbors of RGCs in the mouse, which is emerging as a major model system for analysis of visual system development and function (Chalupa and Williams, 2008). Neither the SC nor the dLGN exhibits clear retinorecipient sublaminae by cytoarchitectural criteria in rodents, unlike the optic tectum of nonmammalian vertebrates and the dLGN of higher mammals. Several studies of individually labeled rodent RGCs demonstrated that those arborizing in upper and lower portions of the retinorecipient region of the SC differ in shape and size (Sachs and Schneider, 1984; Hofbauer and Dräger, 1985; Mooney and Rhoades, 1990). These studies did not, however, identify the morphologically defined RGC subtypes from which the axons arose. Conversely, several recent studies have used transgenic mouse lines that label distinct RGC subtypes to mark axonal termination zones in the SC or LGN (Hattar et al., 2006; Huberman et al., 2008, 2009; Kim et al., 2008, 2010; Siegert et al., 2009), but these studies did not analyze individual arbors.

Here, using transgenic lines and viral vectors to mark individual cells, we matched the dendritic arbors of mouse RGCs to their axonal arbors in the SC. First, we asked whether RGC subtypes defined by their dendritic morphologies also have stereotypic axon arbor morphologies. We analyzed 12 distinct RGC subtypes defined by dendritic morphologies, most of which correspond to previously defined RGC types (Badea and Nathans, 2004; Kong et al., 2005; Coombs et al., 2006; Völgyi et al., 2009). In each case, subsets defined by dendrite morphology showed considerable stereotypy of their axonal arbors. We then asked whether there is a systematic relationship between features of an RGC's dendrites and axon arbors. We found no obvious relationship between dendrite lamination in the retina and relative depth of the axon arbor in the retinorecipient sublaminae in the SC. There was, however, a significant correlation between dendritic field area in retina and arbor depth in the SC. Moreover, taken together with previous electrophysiological studies, our results suggest that multiple RGC subtypes specialized to transmit similar visual features, such as direction selectivity, may project to similar depths in the SC.

Materials and Methods

Transgenic animals

JAM-B-CreER (Kim et al., 2008) and FSTL4-CreER (Kim et al., 2010) mice were crossed with Thy1-lox-stop-lox-YFP15 (Buffelli et al., 2003) mice. CreER-mediated excision of the stop signal results in yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) expression in cells expressing the JAMB- or FSTL4 transgene. RGCs marked by these transgenic lines are referred to here as J-RGCs and BD-RGCs, respectively. For CreER-mediated recombination, Tamoxifen (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) was solubilized by sonication in corn oil and animals were injected at 1.5-2 μg/g for low doses, and 100 μg/g for high doses of injection. Animals were injected subcutaneously at postnatal day (P)0-P5.

W3 and W7 mice, which express green fluorescent protein (GFP) in subsets of RGCs, were also generated in our laboratory and have been described previously (Kim et al., 2010). DRD4 and CB2 mice were obtained from MMRRC (http://www.mmrrc.org/strains/231/0231.html) (Gong et al., 2003; Huberman et al., 2008, 2009). All mice were maintained on a C57/BL6 background. Animal procedures were in compliance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the Animal and Care and Use Program at Harvard University.

Viral vectors

pAAV-CBA-YC3.6-WPRE was obtained from Brian Bacskai (Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Charlestown, MA). YC3.6 is a calcium sensor that combines YFP and CFP (Nagai et al., 2004; Kuchibhotla et al., 2008), but we used it purely to visualize neuronal morphology. Recombinant AAV2/2 (rAAV)-Cre and rAAV2/2-YC3.6 were generated at the Harvard Gene Therapy Institute (Boston, MA). Viral stock titers were 1–2 × 1012 genome copies/mL. Optimal viral titers were determined by testing serial dilutions in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH = 7.4); retinal injection of 1.5–2 μL of a 1–2 × 109 viral genome particles/mL stock labeled 1-20 RGCs per retina.

For virus injection, mice were anesthetized with ketamine/xylazine by intraperitoneal injection. A small hole was made in the temporal eye by gently puncturing the sclera below the cornea with a 30½G needle. Using a Hamilton syringe, 1.5–2 μL of rAAV virus was injected intravitreally with a 33G blunt-ended needle. After injections, animals were allowed to recover by injecting Anti-sedan and monitored for full recovery. Recombinant AAV-YC3.6 expression peaked between 5–8 weeks postinjection, while Thy1-Stop-YFP animals injected with rAAV Cre showed YFP expression by 2–3 weeks. Recombinant AAV-YC3.6 was injected into wildtype animals and rAAV-CRE was injected into Thy1-lox-stop-lox-YFP15 mice.

Antibody characterization

We used the following antibodies, as listed in Table 1.

Table 1. List of Antibodies Used.

| Antigen | Immunogen | Manufacturer, species, catalog number | Dilution used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Choline acetyl transferase (ChAT) | Purified ChAT from human placenta | Millipore Goat polyclonal AB144P | 1:500 |

| Vesicular acetyl choline transferase (VAChT) | A peptide corresponding to amino acids 511-530 of rat VAChT: CSPPGPFDGCEDDYNYYSRS | Abcam goat polyclonal AB34852 | 1:500 |

| Green fluorescent protein (GFP) | Highly purified native GFP from Aequorea victoria. | Millipore, AB3080P, rabbit polyclonal | 1:1,000-1:3,000 |

Anti-choline acetyl transferase (ChAT): The antibody to ChAT detects a single 68–72-kDa band on immunoblots from mouse brain lysates. It labels only cholinergic neurons in the striatum as shown by abrogation of staining following immunodepletion of cholinergic neurons (Kitabatake et al., 2003).

Anti-vesicular acetyl choline transferase (VAChT) was generated using a synthetic 20 amino acid sequence peptide from the rat VAChT protein sequence corresponding to amino acids 511–530 of the carboxy terminus: CSPPGPFDGCEDDYNYYSRS. The peptide was conjugated with thyroglobulin using a glutaraldehyde linker. It does not react with the vesicular monoamine transporter (manufacturer's specifications; Arvidsson et al., 1997). The staining pattern we observed within the IPL of the retina is similar to that reported for ChAT in previous studies (Stacy et al., 2005; Voinescu et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2010).

The antibody to GFP was made against purified native GFP from Aequorea victoria. It is reactive with GFP from both native and recombinant sources (manufacturer's specifications) and does not stain tissue from wildtype mice.

Tissue preparation and immunohistochemistry

Animals were anesthetized with Nembutal and transcardially perfused with 0.1M PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS. Immediately following perfusion, animals were decapitated and tissue was placed on ice. A small hole was made in the globe of the eyeball with a 26G syringe needle to mark the nasal retina, then eyes were removed and retinas were dissected. The nasal pole was further marked by a small radial incision in the retina. The isolated retina was postfixed for 20–30 minutes in 4% PFA on ice, rinsed in PBS, incubated for 1–2 hours in blocking buffer (0.5% Triton-X, 4% normal donkey serum in PBS), then incubated for 3–7 days at 4°C with rabbit antibody to GFP and goat antibody to VAChT. Following thorough washing, the retina was incubated for 24–48 hours at 4°C with donkey anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa 488 and donkey anti-goat IgG conjugated to Alexa 594 (Invitrogen, La Jolla, CA) and PO-PRO1 (Invitrogen, 435/455 nm excitation/emission) to label cell nuclei. Four radial incisions were then made in the retina, resulting in a clover-shaped structure that was flattened, photoreceptor side down, on a 45 μm pore-size nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). The flattened retina and filter were then mounted on a slide with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), coverslipped, and sealed with nail polish.

Brains were dissected following perfusion, incubated in 4% PFA/PBS overnight at 4°C, rinsed in PBS, and sectioned sagittally at 100 μm with a Vibratome (Leica Systems, Deerfield, IL). Serial sections were collected, incubated in blocking solution and primary and secondary antibodies, and mounted as described for retina, except that incubation in primary antibody was for 24–48 hours and goat anti-ChAT was substituted for anti-VAChT.

Image analysis

Retinas and brain sections were initially screened using an epifluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Thornwood, NY), then regions of interest were imaged using a laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with 440, 515, and 568 nm lasers (Olympus FluoView FV1000). Images were analyzed using ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD), MatLab (MathWorks, Natick, MA), or Imaris (Bitplane, St. Paul, MN). One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni multiple comparison tests were used for statistical analysis. Correlation analysis was done using Pearson correlation analysis. For image presentation purposes, confocal image stacks were Gaussian-filtered, gamma-corrected, and maximum intensity projections were generated. In order to emphasize contours of cells, image contrast was inverted such that labeled cells are depicted in black on a white background.

RGC dendritic field area was determined by the smallest bounding polygon that connected the tips of the dendrites from maximum intensity projection images, as in previous studies (e.g., Badea and Nathans, 2004; Kong et al., 2005).

Bouton size was determined by the largest cross-sectional area in μm2 of individual varicosities from confocal image stacks. Axons were selected from well-perfused animals, as assessed by the absence of varicosities in the primary axons of labeled RGC terminals.

RGC asymmetry was quantified by measuring the distance between the center of mass of the soma and that of the dendrites, divided by the dendrite diameter. A perfectly symmetric cell would have an asymmetry index value of 0. The index value approaches 1 with increasing asymmetry.

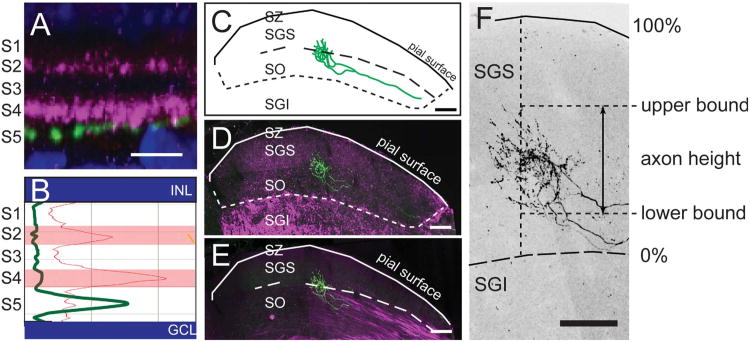

Laminar position of RGC dendrites in the IPL was assessed using VAChT as a reference marker. The IPL was divided into five layers, S1–5, using a nuclear counterstain to delineate the borders of the inner nuclear and ganglion cell layers and staining against VAChT to label S2 and S4. The regions between the inner border of the inner nuclear layer (INL) and S2, between S2 and S4, and between S4 and the outer border of the ganglion cell layer were defined as S1, S3, and S5, respectively (Fig. 1A,B). RGCs were imaged en face in wholemount retinae by confocal microscopy at three different wavelengths to separately image nuclei, VAChT, and YFP. The positions of YFP-positive dendrites were assessed relative to the VAChT-positive sublaminae via maximum intensity projections of 90° rotations of image stacks (Fig. 1B). In cases where dendrites were oblique to the imaging plane, 3D renderings of images were rotated and compared to VAChT-positive planes, or individual optical sections were examined for overlap.

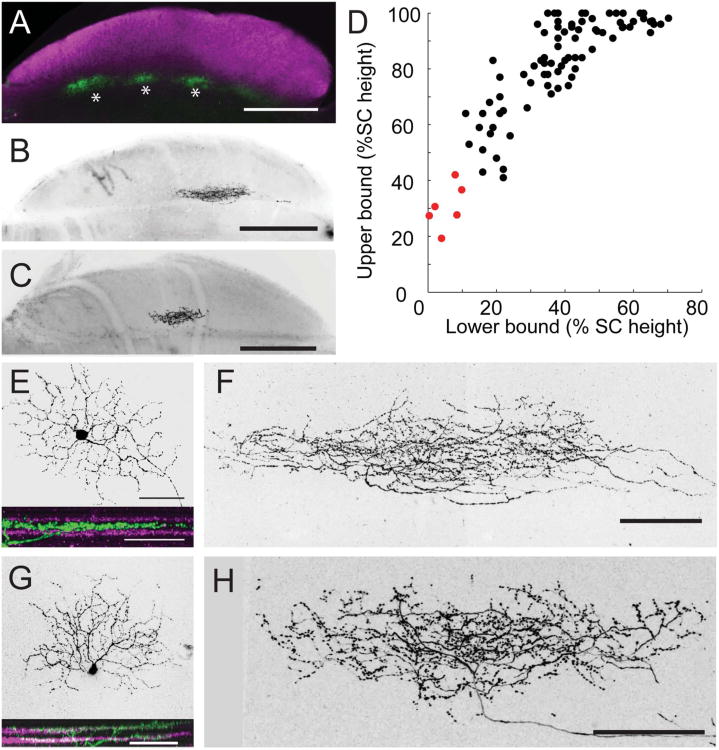

Figure 1.

Fiduciary markers for IPL division in the retina and retinorecipient boundary of the SC. A: Rotation of a confocal image stack showing the IPL lamination of an RGC dendrite (green). VAChT (magenta) serves as a fiduciary marker to divide the IPL into five sublaminae with VAChT-positive bands defined as S2 and S4. Nuclear staining (blue, PO-PRO1) marks the outer boundaries of the IPL. B: Fluorescence intensity profile confirming dendrite position in layer S5. C: Sketch of a retinal arbor in the superior colliculus (SC). The stratum zonale (SZ), stratum griseum superficiale (SGS), and stratum optical (SO) make up the retinorecipient layers. D: ChAT (magenta) labels the stratum griseum intermediale (SGI), demarcating the lower boundary of the retinorecipient zone. E: The SO is delineated by its high density of myelinated fibers (magenta, imaged by confocal reflection). F: The upper and lower boundaries of axonal arbors in the SC were defined by the presence of varicosities along the axon branches. The distance between these boundaries is the axon height. The total height of the retinorecipient SC (dotted line) is the distance from the pial surface to the SGS-SGI boundary delineated by ChAT staining (long dashed line). The pial surface of the SC is designated as 100%; the lower boundary of the retinorecipient SC as 0%. C is a sketch and F is a higher-magnification maximum intensity projection of the axon shown in D and E. Scale bars = 10 μm for A; 100 μm for C–F.

Laminar position of RGC axons

RGC axons enter the SC through the stratum opticum (SO), and arborize within this layer or within the two more superficial layers, stratum zonale (SZ), a thin cell layer just below the pial surface, and stratum griseum superficiale (SGS), where most of the retinal axons terminate (Fig. 1C). We found that the stratum griseum intermediale (SGI), directly beneath the SO, is rich in ChAT-positive fibers (Fig. 1D). We therefore used ChAT staining to mark the deep boundary of the retinorecipient zone and the pial surface to mark its superficial boundary. An abrupt decrease in the density of myelinated fibers marks the boundary between the SO and the SGS (Fig. 1E). The upper and lower boundaries of individual axon arbors (Fig. 1F) were determined from the maximum intensity projection image viewed from the sagittal plane, measured by the maximum and minimum vertical limits of the smallest surrounding polygon of the axon arbor region containing boutons along the axon.

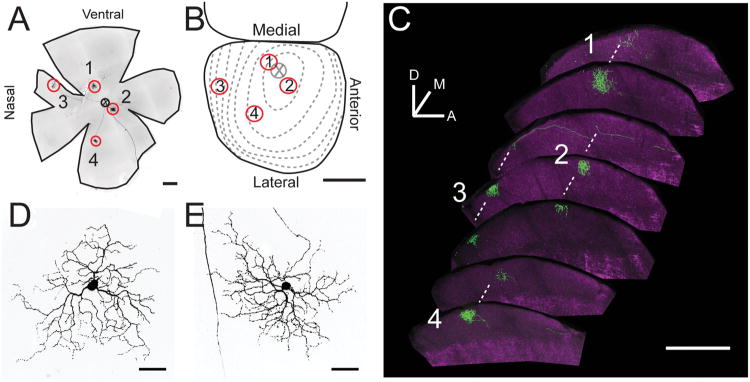

Matching RGC dendrites to axons

Individual RGCs in the retina were paired to their axon arbors by comparing the location in the retina to that of the axon arbor in the SC (Fig. 2). Correspondence was based on the known topographic mapping of the retina on the contralateral SC in rodents (Dräger and Hubel, 1976; Sachs and Schneider, 1984). When retinas from virus-injected animals contained 1–8 YFP-positive RGCs, the corresponding brains were sectioned, stained, and screened for YFP-positive axons. Positions of each RGC soma and axonal arbor were mapped on low-resolution images of the wholemount retina and serial sections of the SC, respectively. High-resolution images of each RGC and axonal arbor were then obtained and analyzed as described above. Labeled cells that had overlapping dendritic fields made retinotopic mapping ambiguous, and were omitted from analysis. In a few cases, axon arbors corresponding to cells in the retina were not found in the SC. This could be due to incomplete labeling, or projection of the RGC to an alternate retinorecipient region. These cells were not studied further. Ipsilaterally projecting axons were identified in animals that had been injected unilaterally.

Figure 2.

Matching dendrites of RGCs to their axon arbors. A: Epifluorescence image of a whole retina (outlined in black) with four YFP-positive RGCs dendrites circled and numbered 1–4. B: Schematic of a dorsal view of the SC with retinal projection map coordinates (Sachs and Schneider, 1984). X represents the optic disk, and dotted contours represent eccentricities in the retina. The positions of RGC axons 1–4 found in C are indicated. C: Sagittal sections of the SC sketched in B, showing four RGC terminals (green). ChAT staining (magenta) outlines the retinorecipient zone. Maximum intensity projections of 100 μm serial sections imaged by confocal microscopy. D,E: Maximum intensity projection of confocal image stacks for RGC-1 (D) and RGC-2 (E) from the retina shown in A. The locations of the axon terminals (B) can be retinotopically matched to the soma locations (A). Orientation bar in C: D, dorsal; M, medial; A, anterior. Black and white images inverted in A, D, and E for clarity. Scale bars = 500 μm in A–C; 50 μm in D,E.

Results

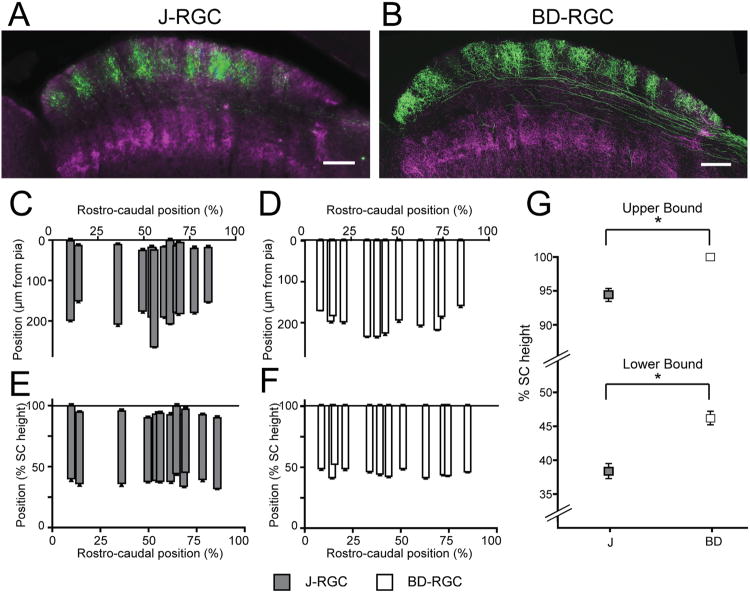

Dendrite and axon characteristics of J- and BD-RGCs

To examine the morphology of RGCs in the retina and their axons, we began by using two sets of double transgenic mice in which functionally distinct RGC subtypes, J- and BD-RGCs, are selectively labeled. J-RGCs are OFF-direction-selective cells that respond to upward motion (Kim et al., 2008), whereas BD-RGCs are ON-OFF direction-selective RGCs (Kim et al., 2010). In both cases, RGCs were labeled using a pair of transgenes, one of which expresses the ligand-activated Cre recombinase, CreER, under the control of cell-type specific regulatory elements, and the other expresses YFP following excision of “STOP” sequences by Cre. For the present work, we used a low dose of tamoxifen so that few RGCs would be labeled and their arbors could therefore be visualized in isolation (see Kim et al., 2010, for explanation).

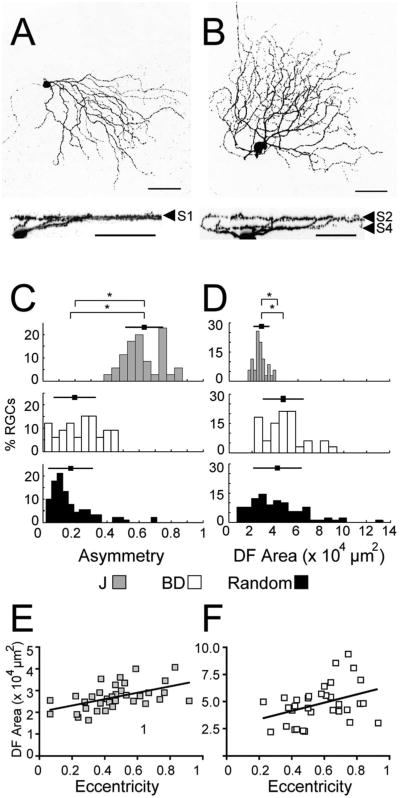

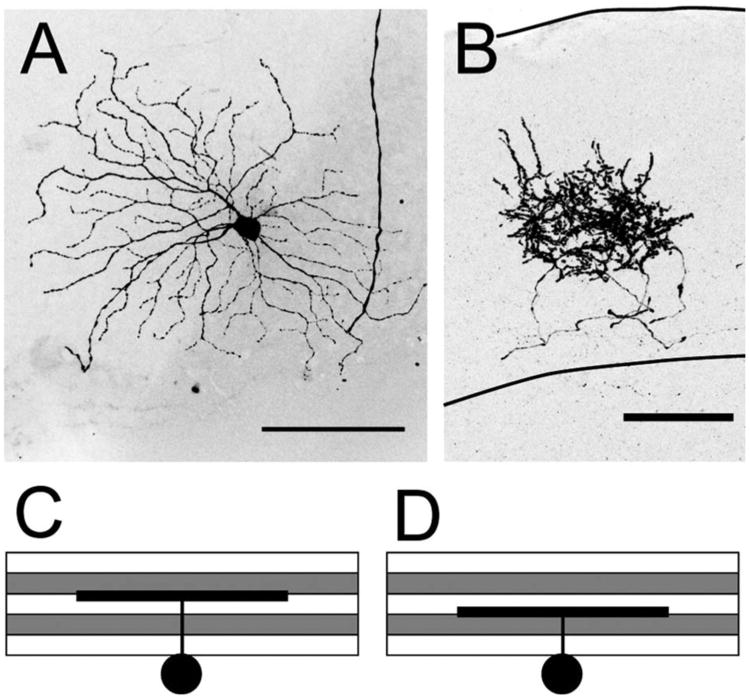

J- and BD-RGC dendritic arbors differ in multiple respects. First, J-RGC dendrites arborize in the S1 sublamina of the IPL, whereas dendrites of BD-RGCs are bistratified in S2 and S4 (Kim et al., 2008, 2010; Fig. 3A,B). Second, the dendrites of J-RGCs were, on average, more asymmetric than those of BD-RGCs, which varied in degree of asymmetry (Fig. 3C). Third, the average dendritic field area of J-RGCs was significantly smaller than those of BD-RGCs (Fig. 3D). BD-RGC dendrites were also more variable in size, with the largest cells found mainly in the periphery of the retina. We also compared J- and BD-RGCs to a population of 89 RGCs that were randomly labeled with rAAV; this set is described further below. J-RGCs are significantly more asymmetric and smaller in dendritic field size than the random population, while BD-RGCs were close to average for both parameters (Fig. 3C,D).

Figure 3.

Dendritic arbors of J- and BD-RGCs. A,B: J- (A) and BD-RGC (B) viewed en face (top panels) and in cross-section (below). J-RGCs laminate in S1 of the IPL, while BD-RGCs laminate in S2 and S4. C: Asymmetry of dendritic arbors (see Materials and Methods). J-RGC arbors are more asymmetric than those of BD-RGCs or a population randomly labeled with rAAV. D: J-RGCs have smaller average dendritic field (DF) area than BD and randomly labeled RGCs. Squares and bars show mean ± SD of each population. (n = 33 J-RGCs, 33 BD-RGCs, and 89 AAV-labeled RGCs, *P < 0.001, Bonferroni multiple comparison test). E,F: The dendritic field areas of both J- and BD-RGCs increase significantly with eccentricity (E, r2 = 0.258; P < 0.01; F, r2 = 0.142; P < 0.05). Scale bars = 50 μm.

In many mammals such as primates and rabbits, the dendritic area of some RGC subtypes increases significantly from the center to the periphery of the retina (Rodieck and Watanabe, 1993; Dacey et al., 2003; Field and Chichilnisky, 2007). In such species, morphometric analysis must take eccentricity into account. In contrast, several studies have shown only small or insignificant differences in dendritic field size with eccentricity in mice (Dräger and Olsen, 1981; Sun et al., 2002; Badea and Nathans, 2004; Schubert et al., 2005a). We used J- and BD-RGCs to reexamine this issue in mice. Both J- and BD-RGCs show a significant increase in dendritic field diameter with eccentricity (Fig. 3E,F; J-RGCs: r2 = 0.26, P < 0.01; BD-RGCs: r2 = 0.14, P < 0.05). However, the difference in diameter is <1.5-fold across the retina. Due to this relatively small variation, we did not include eccentricity measurements in our analysis.

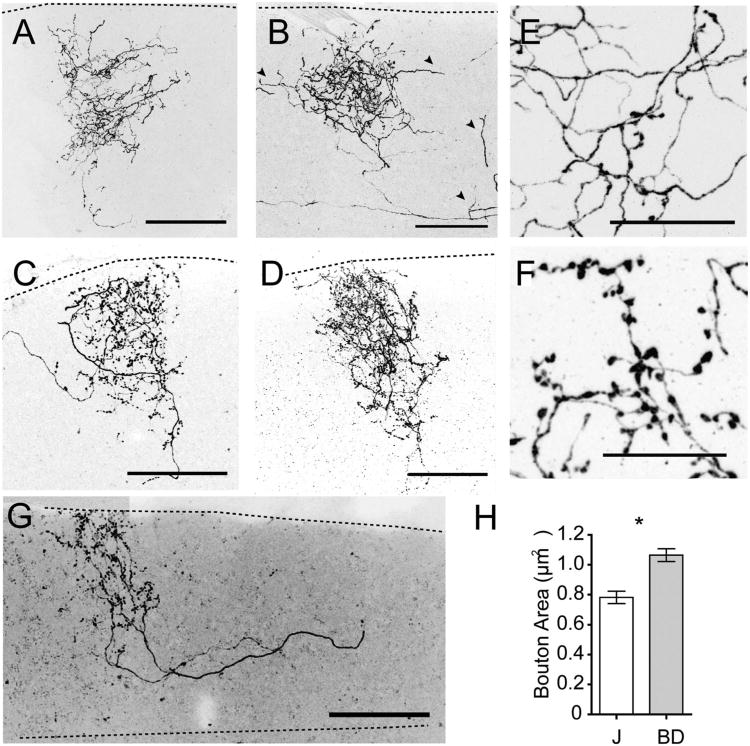

Are the axonal arbors of J- and BD-RGCs as stereotyped as their dendritic arbors? We reconstructed axons of 12 RGCs of each category in the SC. Both sets of arbors were similar in several respects. The primary axons traversed rostrocaudally through the SO then turned dorsally towards the pia. The primary axon formed a few primary branches, which branched further and formed complex and dense arbors that contained hundreds of synaptic boutons (Fig. 4A–F). In each case, axonal arbors extended close to the pial surface, confined to an area that broadly spanned the superficial half of the SC. Some primary axons branched well before entering the retinorecipient zone and forming terminal arbors. In these cases, the trajectories of the branches eventually converged, so that the terminal arbors of both branches overlapped within a single cluster (Fig. 4G).

Figure 4.

Axon arbor morphologies of J- and BD-RGCs. A–F: Arbors of J-RGCs (A,B) and BD-RGCs (C,D) in the SC. Axon branches that wander from the main axon terminal are frequently found in J-RGC (arrowheads in B), but seldom in BD-RGC axons. E,F: Higher-magnification image of portion of J-RGC (E) and BD-RGC (F) arbors. G: BD arbor with diverging branches that eventually converge into a single cluster. H: Bouton sizes in J-RGC (n = 193) and BD-RGC (n = 272) arbors (*P < 0.0001, two-tailed t-test). Dotted lines delineate SC upper or lower boundaries. Scale bars = 100 μm in A–D; 20 μm in E,F.

Despite these similarities, morphologies of BD-axons differed significantly from those of J-RGCs in several respects. First, BD axon arbors were most often tightly clustered with few axon branches deviating from the main cluster (Fig. 4C,D). J-RGC axons, in contrast, were irregularly shaped with a single axon branches sparsely wandering away from the main cluster (Fig. 4A,B). Second, the average width of axon arbors was larger for J-RGCs (177 μm ± 28 μm, mean ± SD) than for BD-RGCs (118 ± 24 μm). Third, within the axon arbor clusters, varicosities of the BD-axons were larger and more spherical than those of J-RGCs (Fig. 4E,F). Overall, boutons of BD-RGCs were ≈ 25% larger than those of J-RGCs (Fig. 4H).

A fourth difference was that BD-RGC axons appeared to be displaced slightly more superficially within the retinorecipient zone compared to J-RGC axons. Analysis was complicated, however, by the curvature of the SC, which results in the retinorecipient zone being taller in central than peripheral SC (Fig. 5A,B). For quantitative analysis, we therefore measured the height of the retinorecipient zone and of individual arbors at multiple locations within the SC (Fig. 5C,D). When arbor height was normalized to SC height at each site, the upper and lower boundaries were relatively uniform for both J- and BD-cells over the central 90% of the tissue (Fig. 5E,F). In contrast, the width of the axon arbors did not vary systematically with location in this area. When the vertical position of the axon is normalized to the SC height at each location, J- and BD-RGCs showed significantly different upper and lower boundaries between the two groups (Fig. 5G). These results indicate that the arbors of J- and BD-RGCs display a striking degree of stereotypy within each subtype.

Figure 5.

RGC axon depth varies in proportion to total SC height. A,B: Densely labeled J-RGC axons (A) and BD-RGC axons (B) in sagittal sections of SC. ChAT labeling (magenta) indicates the lower boundary of the superficial SC. B is from the same section shown in Kim et al. (2010). C,D: Individual axons of J- (C) or BD-RGCs (D) measured from sections along the mediolateral axis and plotted along the rostrocaudal axis (percent of the full rostrocaudal position in the given section). Positions are represented by the distance from the pial surface in μm. E,F: Arbor heights of axons in C and D normalized to the total height of the SC at each location. G: The mean upper and lower boundaries of J- and BD-RGCs. Error bars are mean and SEM. *P < 0.001, two-tailed t-test. Scale bars = 200 μm.

Thus, two subtypes of functionally defined RGCs that have different dendritic morphologies and laminar positions in the IPL also have distinct axonal arbor morphologies and laminar positions in the SC. Moreover, within each population the axon arbors were highly stereotyped.

Stereotyped axonal arbors of RGC subtypes identified by viral labeling

We next asked whether the conclusions derived from analysis of J- and BD-RGCs could be generalized to other RGC subtypes. Because other available transgenic lines label multiple RGC subtypes, or too many cells to permit satisfactory visualization of individual arbors, we used rAAV to sparsely label RGCs with fluorescent proteins. We paired the dendritic morphology with its corresponding axon arbor in the SC using retinotopy, obviating the need for tracing each individual axon along the length of the optic nerve (Fig. 2; see Materials and Methods).

We analyzed 89 RGCs in which contralateral axons were paired to dendrites. Cells were first grouped into categories based on IPL lamination and dendritic area. These parameters are thought to be the most physiologically relevant morphological features (Kong et al., 2005) and are commonly used in morphological classification studies (Sun et al., 2002; Badea and Nathans, 2004; Kong et al., 2005; Coombs et al., 2006; Völgyi et al., 2009). With VAChT staining as a laminar marker to divide the IPL into five distinct sublayers, we were able to consistently compare dendrite position of cells throughout the retina (Fig. 1). Cells within groups were then reexamined to assess the density and shape of the dendritic arbor. In some cases, differences in these parameters led to further divisions into separate classes. Table 2 lists 12 classes for which we found three or more members. As shown in Table 3, many classes corresponded to those described previously (Sun et al., 2002; Badea and Nathans, 2004; Kong et al., 2005; Coombs et al., 2006; Völgyi et al., 2009). However, we refer to these categories as X1–X12 because in a few cases we are unsure of the correspondences between our categories and those defined previously and also because there is not yet a generally accepted nomenclature for mouse RGC subsets.

Table 2. Quantified Parameters of RGC Categories X1-12.

| RGC category | n | IPL | Dendritic field area (μm2) | Soma area (μm2) | Axon upper bound (%SC height) | Axon lower bound (%SC height) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | 3 | 1 | 27347 ± 4.2E+03 | 233 ± 122 | 97 ± 3 | 42 ± 4 |

| X3 | 5 | 1 | 45882 ± 1.4E+04 | 218 ± 64 | 55 ± 10 | 17 ± 4 |

| X4 | 3 | 2 | 23620 ± 8.2E+03 | 178 ± 11 | 80 ± 6 | 40 ± 5 |

| X5 | 5 | 3 | 52556 ± 1.3E+04 | 272 ± 72 | 68 ±10 | 22 ± 8 |

| X6 | 3 | 3 | 44633 ± 7.8E+03 | 204 ± 56 | 97 ± 3 | 59 ± 9 |

| X7 | 8 | 5 | 59895 ± 1.6E+04 | 335 ± 70 | 59 ± 12 | 25 ± 9 |

| X8 | 4 | 1&3 | 11755 ± 4.5E+03 | 128 ± 22 | 95 ± 3 | 61 ± 7 |

| X9 | 5 | 1&4 | 23322 ± 7.1E+03 | 139 ± 19 | 98 ± 2 | 62 ± 7 |

| X10 | 8 | 1&4 | 57393 ± 1.8E+04 | 210 ± 59 | 84 ± 17 | 38 ± 7 |

| X11 | 22 | 2&4 | 43031 ± 2.3E+04 | 169 ± 43 | 96 ± 5 | 48 ± 10 |

| X12 | 4 | 1&5 | 81619 ± 1.2E+04 | 200 ± 50 | 59 ± 5 | 24 ± 5 |

This table contains data on classes for which there were ≥3 members. The IPL was divided into five sublaminae (S1-5) by VAChT staining. Upper and lower boundaries of the axon arbor were normalized to the height of the retinorecipient zone, with the pial surface being 100% and the superficial border of the ChAT-stained band being 0%. Values are mean and SD.

Table 3. Relationship of RGC Classes Analyzed in This Study to Those Previously Defined.

| Category | Sun et al., 2002 | Badea and Nathans, 2004 | Kong et al., 2005 | Coombs et al., 2006 | Vögyi et al., 2009 | Functional equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X1 | C6 | 6 | — | 5a | G15 | OFF-direction selective (Kim et al., 2008) |

| X2 | B3 outer | 3 | 6 | 7 off | G7 | |

| X3 | A2 outer | 7 | 10 | 9 off | G3 | OFF- α sustained (Pang et al., 2003; Schubert et al., 2005a; van Wyk et al., 2009, Völgyi et al., 2005) |

| X4 | B4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | G4 | |

| X5 | C2 outer | 8 | 9 | 9 off | G11 | OFF-α transient (Huberman et al., 2008; Münch et al., 2009; Pang et al., 2003; van Wyk et al., 2009) |

| X6 | — | 2/9 | 7 | 7 on/8on | G9 | |

| X7 | A1, A2 inner | 9 | 8/11 | 9, 10 on | G1/G2/G10 | ON- α sustained (Pang et al., 2003; Schubert et al., 2005a; van Wyk et al., 2009; Völgyi et al., 2005) Intrinsically photosensitive RGC (Ecker et al., 2010) |

| X8 | B2 | 4 | 1 | 11 | G5 | ON-OFF object motion sensitive (Kim et al., 2010) |

| X9 | — | 5 | — | 13 | G20 | |

| X10 | — | bi 2 | — | 12 | G17/22 | |

| X11 | D1/ D2 | bi 1/bi 2 | — | 12,/13 | G16/G17 | ON-OFF direction selective (Huberman et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2010) |

| X12 | — | bi 3 | — | G12 | Intrinsically photosensitive, melanopsin-positive M3 (Ecker et al., 2010; Viney et al., 2007) |

RGC categories X1-12 from this study are compared to previously defined morphological classes to which they best correspond. In several cases functional properties have been paired with morphological classes and are listed in the last column.

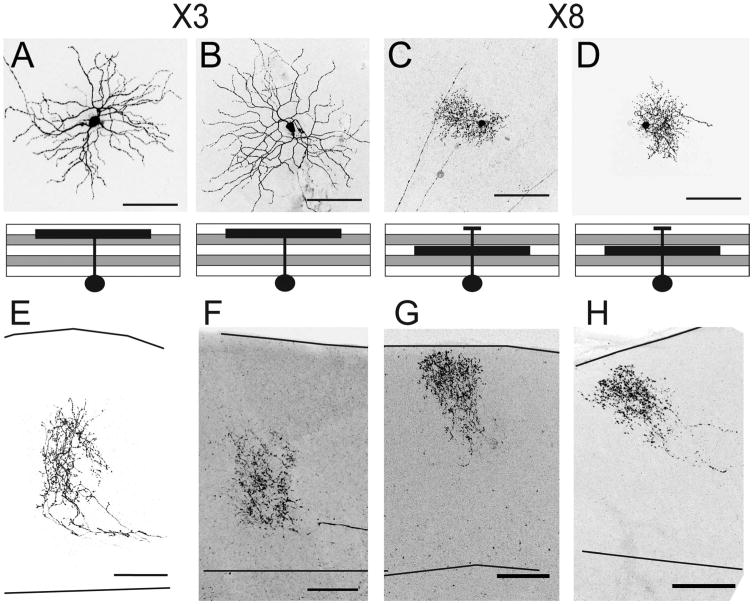

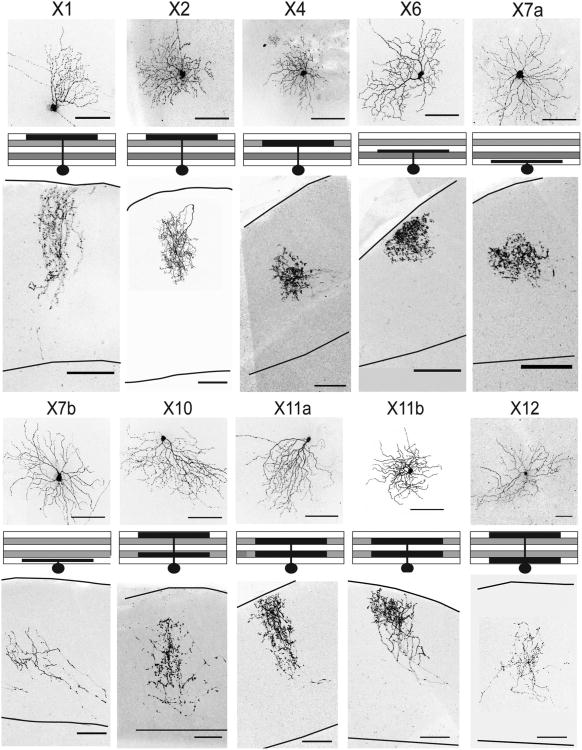

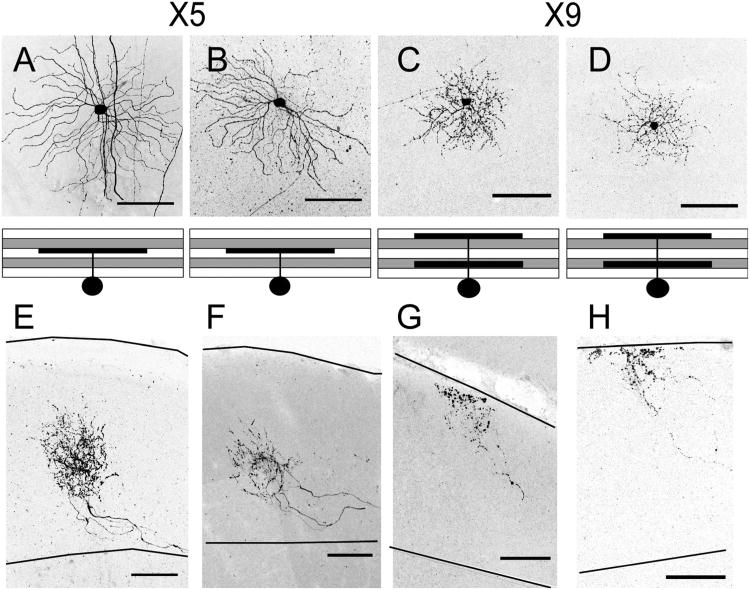

We asked whether axonal arbors of RGCs within each of these 12 sets were stereotyped in terms of size, shape, and laminar position within the retinorecipient zone of the SC. Overall, variation among axonal arbors within each of these 12 sets was strikingly less than variation between categories. Figures 6–8 show arbors of RGCs in each of the 12 classes. For four of the classes, two representative examples are shown to demonstrate the stereotypy of their dendritic and axonal arbors (Figs. 6, 7). Figure 8 shows single examples of RGC dendritic and axonal arbors of the other eight categories. Quantitative measurements are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 6.

Dendrites and axonal arbors of X3 and X8 RGCs. A–D: Two X3 RGCs (A,B) and two X8 RGCs (C,D). In each case the top pane shows an en face view and the bottom panel is a schematic of the 90° rotation image. X3 RGC dendrites laminate in layers S1 and S2; X8 RGC dendrites laminate in S3 with a minor projection to S1). E–H: The axons of A–D, respectively. X3 RGCs have axons in the deep layers of the SC (E,F). X8 RGCs have densely arborizing axons in the superficial SC (G,H). Solid lines indicate pial surface and lower boundary of retinorecipient SC. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Figure 8.

Dendrites and axonal arbors of X1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 10, and 11 RGCs. Top panels are en face views of dendrites in the retina; positions of their dendrites in the IPL are shown schematically beneath. The bottom panel of each set shows axon terminals of the RGC in the SC, from serial sagittal sections. Images are maximum intensity projections of confocal image stacks. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Figure 7.

Dendrites and axonal arbors of X5 and X9 RGCs. A–D: Two X5 RGCs (A,B) and two X9 RGCs (C,D). In each case, the top pane shows an en face view and the bottom panel is a schematic of the 90° rotation image. X5 RGC dendrites laminate in the upper portion of S3 (A,B). X9 RGC dendrites are bistratified with arbors in S1 and S4 (C,D). E–H: The axons of A–D, respectively. X5 RGCs have axons in the deep layers of the SC (E,F). X9 axons are relatively sparse and have varicosities concentrated at the superficial region of the SC (G,H). Solid lines indicate pial surface and lower boundary of retinorecipient SC. Scale bars = 100 μm.

X1 cells (n = 3) had small, asymmetric dendrites that pointed towards the ventral retina and laminated in S1 of the IPL. Cells in this class were indistinguishable from J-RGCs (Kim et al., 2008) in both dendritic and axonal morphology. The upper and lower boundaries were also similar to those of J-RGCs. X1 axons represented the tallest among those examined, spanning 50–60% of the upper SC (Fig. 8).

X2 cell (n = 14) dendrites were medium-sized and also laminated in S1 layer of the IPL, but were distinguishable from X1 cells in that their dendrites were significantly larger and more symmetric (asymmetry index = 0.63 for X1 compared with 0.13 for X2). X2 axon arbors were situated slightly deeper in the SC than those of X1 cells (Fig. 8).

X3 cells (n = 5) dendrites laminated in primarily in S1 of the IPL but extended into S2. They were distinguishable from X1 and X2 cells by their large dendritic field sizes and sparse dendrites that rarely overlapped, and large somata. These cells were similar in morphology to previously described OFF-a sustained cells (Volgyi et al., 2005, 2009; van Wyk et al., 2009). The cells of this class had axon arbors that were restricted to the deep SC (Fig. 6).

X4 cells (n = 3) had small dendrites that costratified with the VAChT-positive band in S2 of the IPL. The axon arbors were restricted to the middle portion of the superficial SC (Fig. 8).

X5 cells (n = 5) had large dendrites and somata that stratified in the upper portion of S3, straddling the S2 VAChT band. They were morphologically similar to cells that have been described as transient OFF-α transient cells (Huberman et al., 2008; van Wyk et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2010). Morphologically, X5 cells were also similar to approach-sensitive RGCs described by Münch et al. (2009). X5 axon arbors, like those of the transient OFF-α cells, laminated in the lower SC (Fig. 7).

X6 cells (n = 3) had medium-sized dendrites that stratified in layer S3, closely apposed to the S4 VAChT layer. The dendrites were relatively sparse and nonoverlapping and had many short and wavy branches. Axon arbors of X5 cells were restricted to the uppermost SC. The morphologies of these arbors were unique in forming dense triangular clusters (Fig. 8).

X7 cells (n = 8) had large dendritic fields and the largest somata (≈330 μm2 area) of the cell types examined. The dendrite branches, which arborized in S5, were sparse with, little overlap, similar to those of X3 and X5 RGCs, which arborized in S1 and S3, respectively. All cells in this category projected to the lower-most regions of the SC but were variable in axon density. Two RGCs of this class had dense arbors (Fig. 8, X7a), while the remaining six had relatively sparse axons (Fig. 8, X7b). We were unable to find significant distinctions between dendritic morphologies of cells in this category. Previous studies have divided S5-laminating RGCs into several classes, but variability within each class makes it difficult to define the classes to which X7 RGCs correspond. Possibilities include ON-α sustained cells (Volgyi et al., 2005) and intrinsically photosensitive type M4 cells (Ecker et al., 2010). Thus, the X7 category may represent multiple RGC subtypes that share dendritic morphology and axonal position but differ in other respects.

X8 cells (n = 4) had the smallest dendritic field area (≈12,000 μm2) and somata (≈130 μm2) of the subtypes we identified. Dendrites broadly and densely spanned the full S3 lamina. There was also a minor projection to the S1 sublamina. These cells corresponded morphologically to a set of ON-OFF motion-sensitive cells that we have previously called W3-RGCs (Kim et al., 2010). The axon arbors were very dense and formed a narrow triangular cluster located in the superficial SC. They were distinct in shape from X6 cells, which also laminated in the upper SC, in that X8 arbors were less dense and more oblong in shape, compared to the triangular axons of X6 RGCs (Figs. 6, 8).

X9 cells (n = 5) had small bistratified dendrites, which laminated in IPL layers S1 and S4. X9 axons arborized in the superficial part of the SC. These arbors were unusual in exhibiting a nonuniform density of varicosities. Deep branches bore few varicosities, but their density increased dramatically in more distal branches, with the majority concentrated in the most superficial portion of the SC near the pial surface (Fig. 7).

X10 cell (n = 4) dendrites were similar to those of X11 cells when viewed en face, but they were 30% larger in dendritic field size and soma area. Moreover, the dendrites of X10 cells laminated primarily in S1 and S4, whereas BD cells laminated in S2 and S4. Axonal arbors of X10 cells were restricted to the middle of the retinorecipient zone in the SC (Fig. 8).

X11 cells (n = 22) were bistratified, with dendrites in S2 and S4 of the IPL. Their dendritic morphology closely resembled that of the BD cells described above. Bistratified RGCs in layer S2 and S4 are ON-OFF direction selective (Huberman et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2010). Several studies have divided S2 and S4 bistratified RGCs into two subgroups (Badea and Nathans, 2004; Coombs et al., 2006; Schubert et al., 2005b; Völgyi et al., 2009). Likewise, cells in the X11 group were somewhat variable in dendritic morphology, primarily distinguishable by dendritic field size (X11a, area 22,300 ± 5,200 μm2, n = 10; X11b, 60,300 ± 17,500 μm2, n = 12). Despite this heterogeneity, all RGCs in this category projected within the upper half of the retinorecipient region of the SC. Height of axonal arbors varied among cells, but there was no detectable relationship of dendritic field size to axon arbor height or location (Fig. 8).

X12 cells (n = 8) had large bistratified dendrites that arborized in S1 and S5. These cells resembled previously described, type 1 bistratified cells (Schubert et al., 2005b), and melanopsin-positive cell type M3 (Viney et al., 2007; Ecker et al., 2010). Their axonal arbors were very sparse and irregularly shaped with fewer varicosities than seen in other axon arbors. Axons were restricted to the lower portion of the SC (Fig. 8).

In summary, for each identified cell class we found that the axon arbors within a class had similar axon arbor morphologies. These results support and extend the conclusion drawn from analysis of J- and BD-RGCs, that RGC subsets classified by dendritic morphology also share stereotyped axonal morphologies.

Ipsilaterally projecting RGCs

Previous studies indicate that 2–3% of RGCs project to the ipsilateral SC. Their somata are located in a ventrotemporal crescent, but only 15% of RGCs within this region project ipsilaterally (Dräger and Hubel, 1975; Dräger and Olsen, 1980). Thus, even in this zone, contralaterally projecting RGCs predominate. Consistent with their concentration in the ventrotemporal retina, the axons of ipsilaterally projecting RGCs target the anteromedial regions of the SC (Hofbauer and Dräger, 1985). To demonstrate the segregation of contralateral and ipsilateral zones of the SC we labeled one retina with cholera toxin subunit B (CTB) conjugated to Alexa 488 and the other with CTB-Alexa 594. As shown in Figure 9A, dye transported from the ipsilateral eye (green) was confined to a narrow swath in patches beneath the retinorecipient zone defined by dye transported from the contralateral eye (magenta).

Figure 9.

Dendrites and axons of ipsilaterally projecting RGCs. A: Retinorecipient zones in SC revealed by Alexa 594-conjugated CTB injected into the contralateral eye (magenta) and Alexa 488-conjugated CTB into the ipsilateral eye (green). Ipsilateral projections are in deepest layers of the superficial SC (asterisks). B,C: single axons originating from the ipsilateral eye in sagittal SC sections. D: Axon positions of ipsilaterally (red circles) and contralaterally projecting axons (black circles) within the SC. E,G: RGC dendrites en face (upper) and cross-sectional views (lower) of the cells that gave rise to arbors in B and C, respectively. F,H: Higher-magnification images of axonal arbors of cells shown in B and C, respectively. Scale bars = 500 μm in A–C; 50 μm in E,G; 100 μm in F,H.

Measurement of individual arbor depth within the SC confirmed the laminar distinction between arbors arising from the two eyes (Fig. 9B–D). For this analysis, eyes were injected unilaterally to ensure unambiguous identification of ipsilateral projections. Six individual arbors of ipsilaterally projecting RGCs were examined. They were elongated along the rostrocaudal axis and were, on average, 2.6 times wider in this dimension than contralaterally projecting axons. Along the mediolateral axis, however, ipsilateral axons were similar in size to contralateral axons with their arbors contained within 1–2 serial sections of 100 μm thickness. The absolute height-to-width ratio of ipsilateral axons (0.24 ± 0.07, mean ± SD, n = 6) was smaller than those of contralaterally projecting cell (1.30 ± 0.5, n = 89). All ipsilaterally projecting cells in this study had the same laminar position within the SC, which was at the deepest margin of the retinorecipient zone.

Do ipsilaterally projecting RGCs, which have similar axonal arbors, correspond to a single class defined intraretinally? Three RGCs projecting to the ipsilateral SC were retinotopically mapped. Two were bistratified cells, while one RGC was monostratified in layer S3 (Fig. 9E–H). This indicates that ipsilaterally projecting cells represent more than a single class of RGCs. Thus, ipsilateral axons break the rule adhered to by contralateral axons: while ipsilateral axons originate from different classes of RGCs, their arbor depth in the SC are homogeneous.

Relationship of dendritic and axonal laminar depth of RGCs

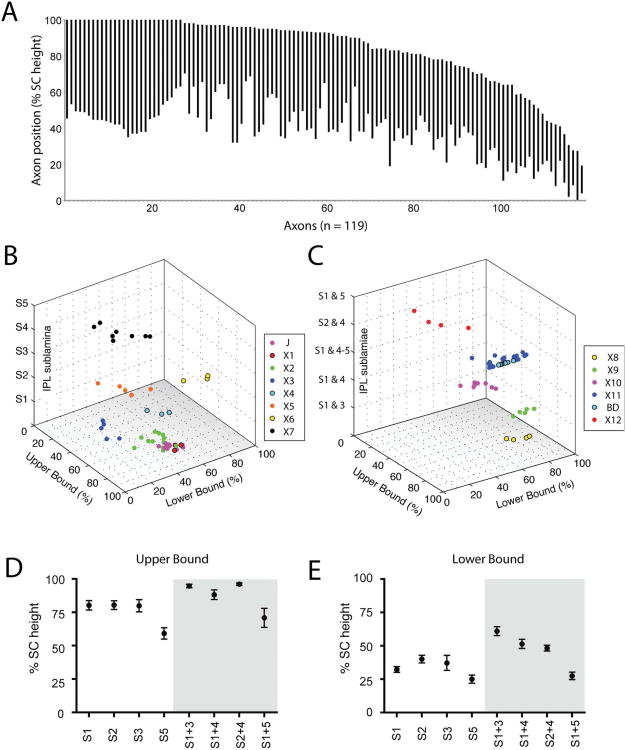

To ask whether axonal arbors of RGCs occupy discrete laminar positions within the SC, we first arranged all 119 axons (89 contralateral, 6 ipsilateral, 12 J-RGC, and 12 BD-RGC) described above in order of the upper, followed by lower boundaries of their axon arbors (Fig. 10A). RGC axons do not form discrete laminae but span broad depths of the SC in a largely overlapping fashion. However, when the cells are grouped by morphological class defined by their dendrites, it is apparent that RGCs of a single class tend to have similar axon arbor depths within the retinorecipient SC (Fig. 10B,C).

Figure 10.

Depth of RGC arbors in the SC. A: Arbor positions of 119 rAAV or transgenically labeled RGC axons. Each bar represents a single RGC arbor in the SC. Arbors are ordered first by the position of the upper boundary within the SC followed by the lower boundary normalized to the total SC height. X axis indicates axons numbered 1–119. B,C: 3D plots of RGC axon positions relative to their lamination in the IPL for monostratified (B) and bistratified RGCs (C) labeled with rAAV. Categories X1–12 are represented in colors indicated. D,E: Location of the upper (D) and lower (E) boundaries of the 119 axon arbors in A, grouped by their IPL lamination.

We next asked whether there was a systematic relationship between the laminar positions of an RGC's dendrites in the retina and its axonal arbor in the SC (Fig. 5D,E). RGCs with dendrites in IPL sublayer S5, regardless of whether they were mono- or bistratified, had axon arbors that were significantly deeper in the SC than other cell categories.

However, no other systematic relationship was found between dendritic sublamina and axon upper or lower bound within the SC.

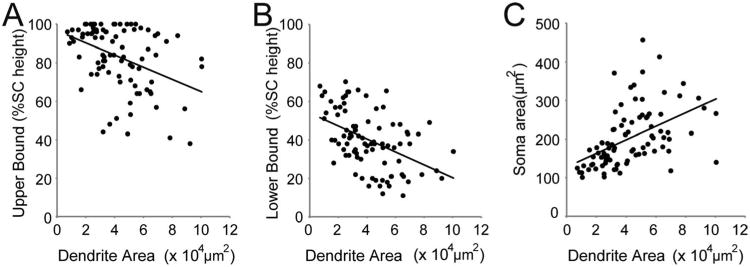

Relationship of dendritic field size to axonal laminar choices of RGCs

We next asked whether the size of the RGC dendritic arbor or soma was related to the laminar position of its axonal arbor. The dendritic field area in the retina was related to arbor depth: RGCs with larger dendritic areas tended to have axons that terminated in deeper regions of the SC. The correlation between dendritic field area and arbor depth was significant for both the upper (Fig. 11A; r2 = 0.15, P < 0.001) and the lower boundary of the axon arbor (Fig. 11B; r2 = 0.22, P < 0.001). The dendritic field area was highly correlated with the soma area (Fig. 11C, r2 = 0.24, P < 0.001; see also Coombs et al., 2006). Accordingly, soma area of RGCs was also correlated with the laminar position of their axonal arbors in the SC (r2 = 0.20, P < 0.001 for upper; r2 = 0.21, P < 0.001 for lower boundary). Hence, cells with larger somata and dendritic fields tended to project to deeper layers of the SC. These results are consistent with inferences made from physiological (Fukuda et al., 1978a,b) and bulk-labeling analyses that measured soma size (Hofbauer and Dräger, 1985).

Figure 11.

Dendritic field area of RGCs is correlated with soma area in retina and arbor depth in the SC. A,B: RGC dendritic field areas of the RGCs shown in Figure 10A plotted against the upper (A) and lower (B) boundary of the axon terminal in the SC, normalized to the SC height. The dendritic field area is negatively correlated with both the upper (r2 = 0.15, Pearson correlation analysis, P < 0.001) and lower (r2 = 0.22, P < 0.001) boundaries. Cells with larger dendritic field areas are located deeper in the SC. C: The dendritic field area is also correlated with the soma area (r2 = 0.24, P < 0.001).

Relationship of RGC function to the depth of its axon arbor

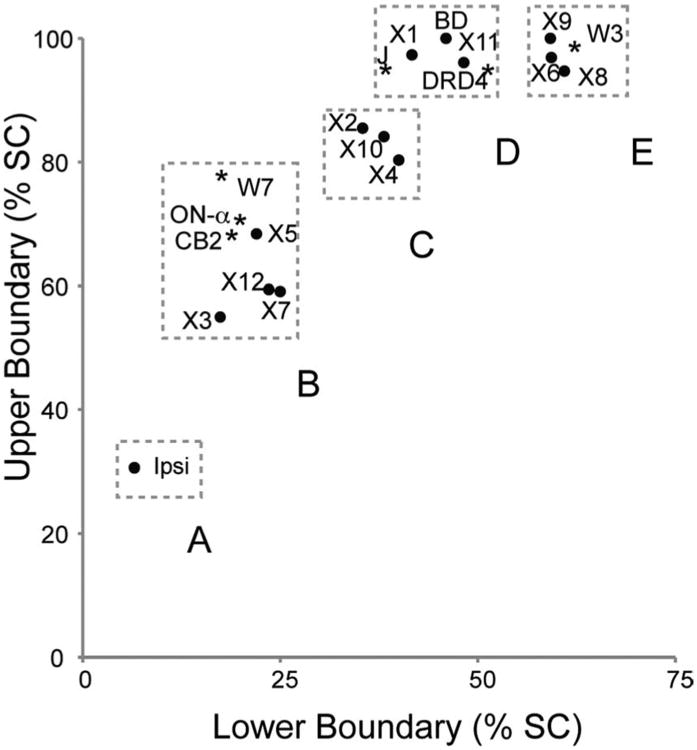

In several cases, the functional properties of morphologically defined RGC subclasses have been defined electrophysiologically or can be inferred from the characteristics of the dendritic arbor (Table 3). We asked whether functionally similar subtypes shared any axonal characteristics. An intriguing relationship emerged from arranging subtypes by the upper and lower boundaries of their axonal arbors. We consider five groups of RGCs that differ in axon arbor depth (Fig. 12).

Figure 12.

RGC categories and axon position in the SC. Axon arbor positions of RGC axons in the SC. Points indicate mean positions of arbors of X1–X12 and ipsilaterally projecting RGCs labeled with AAV as well as J-, BD, W3-, CB2-, and DRD4-RGCs marked in transgenic lines (Kim et al., 2008, 2010; Huberman et al., 2008, 2009). In addition, the location of an ON-α RGC (see Fig 13) is shown in cluster B. Boxes highlight clustering of arbor positions into five groups (A–E). See text for details.

Cluster A

Axons that project ipsilaterally arise from multiple RGC subtypes but share a laminar position in the deepest portion of the retinorecipient SC. The axon arbors from ipsilateral projections had lower boundaries that were deeper than any contralateral axon observed. Thus, information required to make judgments about binocularity is segregated to a restricted laminar depth.

Cluster B

Axons of RGCs in categories X3, X5, and X7 occupied a stratum deep within the retinorecipient zone of the SC but superficial to the stratum containing ipsilaterally derived arbors. Dendritic arbors of these subsets occupied various sublaminae within the inner plexiform layer (S1, S2/3, and S5, respectively), but were similar in shape: all had large dendritic fields with large somata and sparse, long dendrites that rarely crossed. Reference to previous studies suggests that these three groups correspond to α-RGCs, which have been described in at least 20 mammalian species (Boycott and Wässle, 1974; Nelson et al., 1978; Bloomfield and Miller, 1986; Peichl et al., 1987a,b), although the functional correspondence of RGC types between species is subject to debate. The RGCs we identified appear to correspond to three types of α-RGCs characterized previously in mice: X3 cells correspond to sustained ON-α cells that arborize in S1; X5 cells correspond to transient OFF-α cells that arborize in S2/3; and X7 cells correspond to sustained OFF-α cells that stratify in S5 (Sun et al., 2002; Pang et al., 2003; Schubert et al., 2005a; van Wyk et al., 2009; Völgyi et al., 2009).

To test the idea that α-RGCs arborize in the deep area marked as Cluster B, we extended our study in three ways. First, we obtained and analyzed CB2-GFP transgenic mice, in which a set of transient OFF-α RGCs are selectively labeled (Huberman et al., 2008). GFP-positive axonal arbors in these mice occupied a position similar to those of X5 cells (≈68% for the upper bound and 19% for the lower bound; Fig. 12). Second, we analyzed axons of RGCs marked in the W7 line that we characterized previously as large cells that have a sustained OFF response to a flashing spot (Kim et al., 2010). Axons of these cells also arborized in the area demarcated by Cluster B. Third, we took account of the finding that α-RGCs occur in paramorphic pairs of ON and OFF cells with similar structural and functional properties but dendrites in different inner plexiform sublaminae. For example, X3 and X7 cells appear to correspond to paramorphic pairs described by Coombs et al. (2006), and Kong et al. (2005; Table 3). We asked whether our collection of images included the paramorphic partner of X5/CB2 cells. In fact, one RGC satisfied this criterion. Its dendritic field resembled that of X5 cells but arborized on the S3/4 border (Fig. 13). The axon of this cell arborized in the region occupied by X3, X5, and X7 arbors (Fig. 12, cluster B, “ON-α,” asterisk). This result supports the idea that a-RGCs share targets in the SC.

Figure 13.

Alpha RGC-like cell with dendrites in lower S3 sublamina. Putative paramorphic pair of cells in the X5 category. A,B: Dendritic (A) and axonal (B) arbors are morphologically similar to those of X5 cells. C: The dendrites of the RGC shown in (A) lie closer to the S4 layer. D: IPL lamination of X5-type RGC shown in Figure 7A. Note that while both cells have dendrites in S3, X5 cells (D) have dendrites distinctly closer to S2, while the RGC shown in (A) has dendrites that straddle the S4 layer of the IPL. Scale bars = 100 μm.

X12 cells also had axon terminals within this cluster. They had the largest dendritic field size among all classes examined. These cells closely resembled the type 3 (M3) melanopsin-positive cells that are bistratified in layers S1 and S5 (Viney et al., 2007; Ecker et al., 2010).

Cluster C

Arbors of X2, X4, and X10 RGCs clustered approximately in the middle of the SC. To our knowledge, no functional studies of these three types have been reported.

Cluster D

J-RGCs and BD-RGCs are OFF and ON-OFF direction-selective RGCs, respectively (Kim et al., 2008, 2010). X1 and X11 RGCs correspond morphologically to the J- and BD-RGCs, respectively. All of these cells have tall columnar arbors situated in the superficial half of the retinorecipient zone, with arbors extending to (BD, X11) or nearly to (J, X1) the pial surface.

Four types of ON-OFF direction-selective RGCs have been described, each selectively responsive to objects moving in a particular direction—roughly dorsal, ventral, nasal, and temporal (Barlow and Levick, 1965; Oyster and Barlow, 1967). We surmise that the X11 group includes cells of four directional preferences. Our electrophysiological studies have shown that BD-RGCs respond preferentially to vertical motion (Y. Zhang, I-J. Kim, J.R. Sanes, and M. Meister, pers. commun.). Recently, Huberman et al. (2009) reported on a mouse transgenic line DRD4-GFP, in which GFP marks ON-OFF direction selective cells that respond to objects moving nasally. These cells are thus distinct from BD-RGCs. We obtained DRD4-GFP mice and measured the region of the SC in which labeled axons terminate. Labeling was dense, so individual arbors could not be visualized, but in aggregate they occupied a zone similar to that occupied by J- and BD-RGCs (Fig. 12, Cluster D). Thus, multiple populations of direction-selective RGCs may share targets in the SC.

Cluster E

Arbors of X6, X8, and X9 RGCs occupy a narrow swath in the superficial SC. X8 cells resemble W3-RGCs cells (Kim et al., 2010), which have been functionally characterized as object motion sensors that respond to motion in the receptive field center only if objects in the surround move with a different trajectory (Y. Zhang, I-J. Kim, J.R. Sanes, and M. Meister, pers. commun.). We assessed axon terminal positions in W3-transgenic mice relative to ChAT staining; arbors were similar in morphology and laminar depth to X8 cells (Fig. 12). Cells with similar physiological properties have been described in salamander and rabbit retina and likely include multiple subtypes (Levick, 1967; Olveczky et al., 2003). It is thus tempting to speculate that X6 and X9 cells might also be object motion sensors. Indeed, one putative local edge detector in rabbit retina arborizes in S3, much like the X6 RGCs (van Wyk et al., 2006).

Discussion

Distinct subsets of RGCs are tuned to specific visual features (Masland, 2001; Gollisch and Meister, 2010). Axons of RGCs carry the information to the brain, where it is processed further to generate percepts and behaviors. In most vertebrate species the main central targets of RGCs are the optic tectum/SC and the dLGN. RGCs of specific types arborize in distinct retinorecipient sublaminae of the optic tectum of nonmammalian vertebrates such as fish and birds, and of the dLGN of many mammalian species, including primates and carnivores (Karten et al., 1982; Yamagata and Sanes, 1995; Dacey, 2000; Xiao and Baier, 2007; Yamagata et al., 2006; Nassi and Callaway, 2009). Our aim here was to ask whether the same is true in the SC of mice, which have emerged recently as a major model system for vision research (Chalupa and Williams, 2008; Sanes and Zipursky, 2010). To this end, we classified RGC subtypes based on their dendritic morphology, knowing that subtypes defined in this way generally share functional attributes (Hattar et al., 2002; Huberman et al., 2008, 2009; Kim et al., 2008, 2010; Ecker et al., 2010). We then analyzed the shapes and positions of the axonal arbors of these cells in the SC.

First, we examined two transgenic mouse lines that label specific subsets of RGCs, J- and BD-RGCs. These cells are OFF-direction selective, and ON-OFF direction selective RGCs, respectively (Kim et al., 2008, 2010). We found that the axon arbors of each class showed considerable stereotypy but that there were significant differences between the two classes. We then extended the analysis to RGCs of 12 additional classes for which we identified three or more exemplars in AAV-labeled retinas. Again, stereotypy was striking within each class, but differences were apparent among classes. Thus, two main conclusions of our study are that RGC subsets with stereotyped dendritic arbors also have stereotyped axonal arbors in the SC, and that RGCs subsets with distinct dendritic morphologies (and, therefore, distinct functions) often have distinct axonal arbor shapes and positions.

Axonal arbors of distinct RGC subsets differed in several respects. First, the arbor height differed among subtypes. The shortest axons spanned less than a third of the height of the SC retinorecipient zone, while the tallest axons spanned >50% of this zone. Second, the width of the axons showed little variability within a subtype but varied among subtypes. Third, arbor depth differed among subtypes. While not forming discrete laminae, axons were confined to various restricted depths in an overlapping fashion. Fourth, while the majority of axons formed dense cylindrical terminal clusters, several types were easily identifiable by differences in the density or shape of the arbor.

A fifth difference among RGC subtypes, which was unexpected, was in the size of their terminal varicosities. The boutons in the axonal arbors of BD-RGCs were significantly larger than those of J-RGCs. Moreover, boutons of X9 cells were unevenly distributed within their arbors, being more numerous in distal than in proximal branches. Because varicosity number and size can vary with fixation condition, we limited quantitative analysis to J- and BD-RGCs for which we had large samples. Bouton size is strongly correlated with the number of active zones and presynaptic vesicles in many synapses, suggesting that bouton size is linked to synaptic function (Harris and Stevens, 1988, 1989; Pierce and Lewin, 1994; Schikorski and Stevens, 1999). Thus, our results suggest that different RGC subtypes provide input to SC neurons that differs not only in type but also in strength.

Having documented differences in axonal arbors among RGC subsets, we asked whether there was a relationship between the dendritic and axonal morphology of RGCs. We found that the extent of the dendritic field and the size of the soma were significantly correlated with axon arbor depth within the SC. Specifically, RGCs with larger dendritic fields and somata tend to bear arbors that stratify in lower portions of the retinorecipient zone. This was true for both mono- and bistratified RGCs. This relationship is consistent with that seen in previous studies, which showed that upper portions of the rodent SC receive input from RGCs with small somata and thin, slow-conducting axons, whereas lower portions receive input from thicker, fast-conducting RGC axons (Fukuda et al., 1978b; Sachs and Schneider, 1984; Hofbauer and Dräer, 1985).

On the other hand, we found no systematic relationship between the laminar position of an RGC's dendrites and the shape, size, or laminar position of its axonal arbor. There was a significant tendency for RGCs with dendrites in the deepest sublamina of the IPL to have axonal arbors in deep regions of the SC. However, multiple RGC subsets with dendrites in other IPL lamina had axon arbors in various depths of the SC. Likewise, RGCs with axons at similar depths within the SC had dendrites that laminated in various layers of the IPL. Similarly, there is no systematic relationship between dendritic and axonal lamination of RGCs in the chick retinotectal system (Yamagata et al., 2006). These results argue against the simple idea that a single set of targeting molecules could promote that laminar patterning of both an RGC's dendrite and its axon.

Correlative studies of structure and function have provided insight into the physiological responses of several RGC subtypes defined morphologically. Consideration of this classification suggests that multiple types with similar function project to a common region. Five clusters of subtypes are diagrammed in Figure 12. Most strikingly, OFF-type direction-selective RGCs and at least two (but more likely four) ON-OFF direction-selective RGCs all have tall axonal arbors confined to the upper half of the retinorecipient zone. Conversely, several groups of alpha cells, which have large receptive fields, project to deeper regions. These cells are generally thought to comprise a high-speed pathway (owing to their large axon caliber) and to provide information about motion but not fine detail (owing to their large dendritic field size). In both of these cases, we tested the idea of functional segregation in the SC by analyzing additional cells or transgenic lines that had not been used for the initial analysis. Thus, alpha cells labeled in the W7 (Kim et al., 2010) and CB2-GFP lines (Huberman et al., 2008) and an ON alpha cell (Fig. 13) all projected to the deep region, while direction-selective RGCs labeled in the DRD4-GFP line (Huberman et al., 2009) projected to the superficial region.

An important next step will be to identify the intrinsic collicular neurons on which RGCs of distinct classes form synapses. Early functional studies in the lower SGS described cells that are associated with responses to movement parameters such as velocity or direction. Collicular cells in the deeper SO layers tend to be fast-habituating and have a tendency to be direction-selective toward upward movements (Fukuda et al., 1978a; Dreher et al., 1985). Recently it has been shown that SC neurons in the upper SGS mediate contour perception and have fairly sharp orientation tuning, properties that had only been attributed to cortical cells (Girman and Lund, 2007). Targets of SC cells lying at different depths also differ. For example, many neurons in the upper SGS project to the dLGN, while many deep in the SO projected to the lateral posterior nucleus (Harting et al., 1991; May, 2006). Thus, mouse RGCs that gather information in different sublaminae of the retina and project to different depths in the SC may send their output to distinct regions for further processing.

Acknowledgments

We thank Z. He for the rAAV-Cre; K. Kuchibohtla and B. Bacsai for the pAAV-CAG-YC3.6 vector; J. Morgan for samples of CB2-GFP tissue; S. Sheu and J. Lichtman for advice and image analysis software; and J. Esch for help with histology.

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Grant numbers: NS029169 (to J.R.S.), K99EY019355 (to I.J.K.), 5F31NS55488 (to Y.K.H.); Grant sponsor: NRSA fellowship (to Y.K.H.).

Literature Cited

- Arvidsson U, Riedl M, Elde R, Meister B. Vesicular acetylcholine transporter (VAChT) protein: a novel and unique marker for cholinergic neurons in the central and peripheral nervous systems. J Comp Neurol. 1997;378:454–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badea TC, Nathans J. Quantitative analysis of neuronal morphologies in the mouse retina visualized by using a genetically directed reporter. J Comp Neurol. 2004;480:331–351. doi: 10.1002/cne.20304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow HB, Levick WR. The mechanism of directionally selective units in rabbit's retina. J Physiol (Lond) 1965;178:477–504. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield SA, Miller RF. A functional organization of ON and OFF pathways in the rabbit retina. J Neurosci. 1986;6:1–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-01-00001.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boycott BB, Wässle H. The morphological types of ganglion cells of the domestic cat's retina. J Physiol (Lond) 1974;240:397–419. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffelli M, Burgess RW, Feng G, Lobe CG, Lichtman JW, Sanes JR. Genetic evidence that relative synaptic efficacy biases the outcome of synaptic competition. Nature. 2003;424:430–434. doi: 10.1038/nature01844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalupa LM, Williams RW. Eye, retina and visual system of the mouse. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs J, van der List D, Wang GY, Chalupa LM. Morphological properties of mouse retinal ganglion cells. Neuroscience. 2006;140:123–136. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacey DM. Parallel pathways for spectral coding in primate retina. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:743–775. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacey DM, Peterson BB, Robinson FR, Gamlin PD. Fireworks in the primate retina: in vitro photodynamics reveals diverse LGN-projecting ganglion cell types. Neuron. 2003;37:15–27. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01143-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dräger UC, Hubel DH. Responses to visual stimulation and relationship between visual, auditory, and somatosensory inputs in mouse superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 1975;38:690–713. doi: 10.1152/jn.1975.38.3.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dräger UC, Hubel DH. Topography of visual and somatosensory projections to mouse superior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 1976;39:91–101. doi: 10.1152/jn.1976.39.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dräger UC, Olsen JF. Origins of crossed and uncrossed retinal projections in pigmented and albino mice. J Comp Neurol. 1980;191:383–412. doi: 10.1002/cne.901910306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dräger UC, Olsen JF. Ganglion cell distribution in the retina of the mouse. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1981;20:285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreher B, Sefton AJ, Ni SY, Nisbett G. The morphology, number, distribution and central projections of Class I retinal ganglion cells in albino and hooded rats. Brain Behav Evol. 1985;26:10–48. doi: 10.1159/000118764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecker JL, Dumitrescu ON, Wong KY, Alam NM, Chen SK, Legates T, Renna JM, Prusky GT, Berson DM, Hattar S. Melanopsin-expressing retinal ganglion-cell photoreceptors: cellular diversity and role in pattern vision. Neuron. 2010;67:49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Famiglietti EV, Jr, Kolb H. Structural basis for ON- and OFF-center responses in retinal ganglion cells. Science. 1976;194:193–195. doi: 10.1126/science.959847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field GD, Chichilnisky EJ. Information processing in the primate retina: circuitry and coding. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:1–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda Y, Suzuki DA, Iwama K. A four group classification of the rat superior collicular cells responding to optic nerve stimulation. Jpn J Physiol. 1978a;28:367–384. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.28.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda Y, Suzuki DA, Iwama K. Characteristics of optic nerve innervation in the rat superior colliculus as revealed by field potential analysis. Jpn J Physiol. 1978b;28:347–365. doi: 10.2170/jjphysiol.28.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girman SV, Lund RD. Most superficial sublamina of rat superior colliculus: neuronal response properties and correlates with perceptual figure-ground segregation. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:161–177. doi: 10.1152/jn.00059.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollisch T, Meister M. Eye smarter than scientists believed: neural computations in circuits of the retina. Neuron. 2010;65:150–164. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong S, Zheng C, Doughty ML, Losos K, Didkovsky N, Schambra UB, Nowak NJ, Joyner A, Leblanc G, Hatten ME, Heintz N. A gene expression atlas of the central nervous system based on bacterial artificial chromosomes. Nature. 2003;425:917–925. doi: 10.1038/nature02033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Stevens JK. Dendritic spines of rat cerebellar Purkinje cells: serial electron microscopy with reference to their biophysical characteristics. J Neurosci. 1988;8:4455–4469. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-12-04455.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Stevens JK. Dendritic spines of CA 1 pyramidal cells in the rat hippocampus: serial electron microscopy with reference to their biophysical characteristics. J Neurosci. 1989;9:2982–2997. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.09-08-02982.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harting JK, Huerta MF, Hashikawa T, van Lieshout DP. Projection of the mammalian superior colliculus upon the dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus: organization of tectogeniculate pathways in nineteen species. J Comp Neurol. 1991;304:275–306. doi: 10.1002/cne.903040210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattar S, Liao HW, Takao M, Berson DM, Yau KW. Melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells: architecture, projections, and intrinsic photosensitivity. Science. 2002;295:1065–1070. doi: 10.1126/science.1069609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattar S, Kumar M, Park A, Tong P, Tung J, Yau KW, Berson DM. Central projections of melanopsin-expressing retinal ganglion cells in the mouse. J Comp Neurol. 2006;497:326–349. doi: 10.1002/cne.20970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofbauer A, Dräger UC. Depth segregation of retinal ganglion cells projecting to mouse superior colliculus. J Comp Neurol. 1985;234:465–474. doi: 10.1002/cne.902340405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huberman AD, Manu M, Koch SM, Susman MW, Lutz AB, Ullian EM, Baccus SA, Barres BA. Architecture and activity-mediated refinement of axonal projections from a mosaic of genetically identified retinal ganglion cells. Neuron. 2008;59:425–438. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huberman AD, Wei W, Elstrott J, Stafford BK, Feller MB, Barres BA. Genetic identification of an on-off direction—selective retinal ganglion cell subtype reveals a layer-specific subcortical map of posterior motion. Neuron. 2009;62:327–334. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karten HJ, Reiner A, Brecha N. Laminar organization and origins of neuropeptides in the avian retina and optic tectum. In: Chan-Palay V, Palay SL, editors. Cytochemical melthods in neuroanatomy. New York: A.R. Liss; 1982. pp. 189–204. [Google Scholar]

- Kim IJ, Zhang Y, Yamagata M, Meister M, Sanes JR. Molecular identification of a retinal cell type that responds to upward motion. Nature. 2008;452:478–482. doi: 10.1038/nature06739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim IJ, Zhang Y, Meister M, Sanes JR. Laminar restriction of retinal ganglion cell dendrites and axons: subtype-specific developmental patterns revealed with transgenic markers. J Neurosci. 2010;30:1452–1462. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4779-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitabatake Y, Hikida T, Watanabe D, Pastan I, Nakanishi S. Impairment of reward-related learning by cholinergiccell ablation in the striatum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7965–7970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1032899100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong JH, Fish DR, Rockhill RL, Masland RH. Diversity of ganglion cells in the mouse retina: unsupervised morphological classification and its limits. J Comp Neurol. 2005;489:293–310. doi: 10.1002/cne.20631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchibhotla K, Goldman S, Lattarulo C, Wu H, Hyman B, Bacskai B. Aβ plaques lead to aberrant regulation of calcium homeostasis in vivo resulting in structural and functional disruption of neuronal networks. Neuron. 2008;59:214–225. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levick WR. Receptive fields and trigger features of ganglion cells in the visual streak of the rabbits retina. J Physiol. 1967;188:285–307. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masland RH. Neuronal diversity in the retina. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2001;11:431–436. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(00)00230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PJ. The mammalian superior colliculus: laminar structure and connections. Prog Brain Res. 2006;151:321–378. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(05)51011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooney RD, Rhoades RW. Relationships between physiological and morphological properties of retinocollicular axons in the hamster. J Neurosci. 1990;10:3164–3177. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-09-03164.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai T, Yamada S, Tominaga T, Ichikawa M, Miyawaki A. Expanded dynamic range of fluorescent indicatorsfor Ca(2+) by circularly permuted yellow fluorescent proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10554–10559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400417101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nassi JJ, Callaway EM. Parallel processing strategies of the primate visual system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:360–372. doi: 10.1038/nrn2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson R, Famiglietti EV, Kolb H. Intracellular staining reveals different levels of stratification for on- and off-center ganglion cells in cat retina. J Neurophysiol. 1978;41:472–483. doi: 10.1152/jn.1978.41.2.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olveczky BP, Baccus SA, Meister M. Segregation of object and background motion in the retina. Nature. 2003;423:401–408. doi: 10.1038/nature01652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyster CW, Barlow HB. Direction-selective units in rabbit retina: distribution of preferred directions. Science. 1967;155:841–842. doi: 10.1126/science.155.3764.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pang JJ, Gao F, Wu SM. Light-evoked excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs to ON and OFF alpha ganglion cells in the mouse retina. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6063–6073. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-14-06063.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peichl L, Wässle H. Morphological identification of on-and off-centre brisk transient (Y) cells in the cat retina. Proc R Soc Lond, B, Biol Sci. 1981;212:139–153. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1981.0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peichl L, Buhl EH, Boycott BB. Alpha ganglion cells in the rabbit retina. J Comp Neurol. 1987a;263:25–41. doi: 10.1002/cne.902630103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peichl L, Ott H, Boycott BB. Alpha ganglion cells in mammalian retinae. Proc R Soc Lond, B, Biol Sci. 1987b;231:169–197. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1987.0040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce JP, Lewin GR. An ultrastructural size principle. Neuroscience. 1994;58:441–446. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockhill RL, Daly FJ, MacNeil MA, Brown SP, Masland RH. The diversity of ganglion cells in a mammalian retina. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3831–3843. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03831.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodieck RW, Watanabe M. Survey of the morphology of macaque retinal ganglion cells that project to the pretectum, superior colliculus, and parvicellular laminae of the lateral geniculate nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1993;338:289–303. doi: 10.1002/cne.903380211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roska B, Werblin F. Vertical interactions across ten parallel, stacked representations in the mammalian retina. Nature. 2001;410:583–587. doi: 10.1038/35069068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachs GM, Schneider GE. The morphology of optic tract axons arborizing in the superior colliculus of the hamster. J Comp Neurol. 1984;230:155–167. doi: 10.1002/cne.902300202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanes JR, Yamagata M. Many paths to synaptic specificity. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:161–195. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schikorski T, Stevens CF. Quantitative fine-structural analysis of olfactory cortical synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4107–4112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert T, Degen J, Willecke K, Hormuzdi SG, Monyer H, Weiler R. Connexin36 mediates gap junctional coupling of alpha-ganglion cells in mouse retina. J Comp Neurol. 2005a;485:191–201. doi: 10.1002/cne.20510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schubert T, Maxeiner S, Krüger O, Willecke K, Weiler R. Connexin45 mediates gap junctional coupling of bistratified ganglion cells in the mouse retina. J Comp Neurol. 2005b;490:29–39. doi: 10.1002/cne.20621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegert S, Scherf BG, Del Punta K, Didkovsky N, Heintz N, Roska B. Genetic address book for retinal cell types. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:1197–1204. doi: 10.1038/nn.2370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy RC, Demas J, Burgess RW, Sanes JR, Wong RO. Disruption and recovery of patterned retinal activity in the absence of acetylcholine. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9347–9357. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1800-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, Li N, He S. Large-scale morphological survey of mouse retinal ganglion cells. J Comp Neurol. 2002;451:115–126. doi: 10.1002/cne.10323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wyk M, Taylor WR, Vaney DI. Local edge detectors: a substrate for fine spatial vision at low temporal frequencies in rabbit retina. J Neurosci. 2006;26:13250–13263. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1991-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wyk M, Wässle H, Taylor WR. Receptive field properties of ON- and OFF-ganglion cells in the mouse retina. Vis Neurosci. 2009;26:297–308. doi: 10.1017/S0952523809990137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]