Abstract

Background: The development of low-cost point-of-care technologies to improve HIV treatment is a major focus of current research in resource-limited settings.

Objective: We assessed associations of body mass index (BMI; in kg/m2) at antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation and weight change after 1 mo of treatment with mortality, morbidity, and CD4 T cell reconstitution.

Design: A prospective cohort of 3389 Tanzanian adults initiating ART enrolled in a multivitamin trial was followed at monthly clinic visits (median: 19.7 mo). Proportional hazard models were used to analyze mortality and morbidity associations, whereas generalized estimating equations were used for CD4 T cell counts.

Results: The median weight change at 1 mo of ART was +2.0% (IQR: −0.4% to +4.6%). The association of weight loss at 1 mo with subsequent mortality varied significantly by baseline BMI (P = 0.011). Participants with ≥2.5% weight loss had 6.43 times (95% CI: 3.78, 10.93 times) the hazard of mortality compared with that of participants with weight gains ≥2.5%, if their baseline BMI was <18.5 but only 2.73 times (95% CI: 1.49, 5.00 times) the hazard of mortality if their baseline BMI was ≥18.5 and <25.0. Weight loss at 1 mo was also associated with incident pneumonia (P = 0.002), oral thrush (P = 0.007), and pulmonary tuberculosis (P < 0.001) but not change in CD4 T cell counts (P > 0.05).

Conclusions: Weight loss as early as 1 mo after ART initiation can identify adults at high risk of adverse outcomes. Studies identifying reasons for and managing early weight loss are needed to improve HIV treatment, with particular urgency for malnourished adults initiating ART. The parent trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT00383669.

INTRODUCTION

Provision of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV-infected individuals is rapidly expanding in sub-Saharan Africa (1). Despite successes in improving treatment access, adults initiating ART in resource-limited settings experience markedly high rates of mortality compared with those of individuals in developed countries, especially during initial months of treatment (2). The development of low-cost point-of-care technologies has become a significant focus of current HIV research to improve treatment outcomes in resource-limited settings (3).

Malnutrition and food insecurity, through a multitude of potential effects including impaired immune function and decreased treatment adherence, have been identified as barriers to greater success of HIV-treatment programs in resource-limited settings (4). Multiple studies have shown that low BMI (in kg/m2) at ART initiation is a strong independent predictor of mortality in HIV-infected adults; however, few studies have examined the association of weight change after treatment initiation and subsequent mortality in resource-limited settings (5–11). Studies in resource-settings have shown weight loss after 3–6 mo of ART is associated with increased risk of mortality, but the majority of deaths (∼70%) for adults initiating ART in resource-limited settings occur within the first 3 mo of treatment (2, 8–11).

Accordingly, we present a cohort study that evaluated the association of weight change at 1 mo of ART initiation with subsequent mortality in HIV-infected Tanzanian adults to capture early deaths. We hypothesized that low baseline BMI at ART initiation and weight loss after 1 mo of treatment would be associated with increased mortality. In addition, we a priori hypothesized that the magnitude of the association of weight loss with mortality would be greater for individuals with low BMI at baseline on the basis of a previous findings in this setting (10). We also present analyses of baseline BMI and weight change at 1 mo of ART with incidence of comorbidities and change in CD4 T cell counts to explore 2 potential pathways for a mortality association.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This prospective cohort study consisted of all HIV-infected adult men and women initiating ART enrolled in a trial of multivitamins (vitamins B complex, C, and E) at high amounts compared with standard amounts of the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) conducted during 2006–2009 in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania (www.clinicaltrials.gov; NCT00383669) (12). Individuals were eligible for the trial if they were aged ≥18 y, HIV infected, initiating ART at enrollment, and intended to stay in Dar es Salaam for ≥2 y. Patients with WHO HIV disease stage IV, a CD4 T cell count <200 cells/μL, or with WHO HIV stage III disease and a CD4 T cell count <350 cells/μL began ART (13). Women who were pregnant or lactating were excluded from the trial. First-line drug combinations included stavudine, lamivudine, nevirapine, zidovudine, and efavirenz. Zidovudine was substituted for stavudine for individuals with peripheral neuropathy or who could not tolerate stavudine. Efavirenz was substituted for nevirapine in patients who could not tolerate nevirapine. Cotrimoxazole prophylaxis was provided when CD4 T cell counts were <200 cells/μL, and treatment of all opportunistic infections was prescribed according to Tanzanian national and WHO guidelines. The primary outcome of the trial was HIV disease progression or death, and there was no significant difference between randomized multivitamin regimens (12).

Assessment of height, weight, and baseline covariates

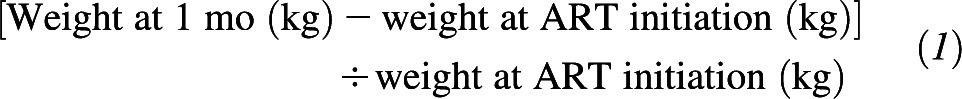

Height and weight were assessed by trained research nurses who used regularly calibrated instruments with standardized procedures at ART initiation. BMI at ART initiation was calculated as the patient's weight divided by the patient's height squared. Anthropometric measurements were also assessed by research nurses at scheduled monthly clinic visits for the duration of enrollment. The percentage of weight change at 1 mo as compared with at ART initiation was calculated as

|

Nurses also obtained socioeconomic data at ART initiation. The number of household assets was calculated from a list of assets that included a sofa, television, radio, refrigerator, and fan. At ART initiation, trained research physicians also performed a complete medical examination and assessed WHO HIV disease stage in accordance with WHO guidelines (13). Blood samples were collected for an assessment of the absolute CD4 T cell count (FACSCalibur system; Becton Dickinson) and a complete blood count (AcT5 Diff AL analyzer; Beckman Coulter).

Assessment of mortality, morbidity, and CD4 T cell count

Study participants were followed at monthly clinic visits, and participants who missed a clinic visit were followed by telephone calls or home visits during which relatives or neighbors were asked about the vital status of the participant. At monthly clinic visits, trained research physicians performed a clinical examination and diagnosed and treated conditions, including opportunistic infections and other comorbidities. Pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infections, Kaposi sarcoma, oral thrush, and extrapulmonary tuberculosis were diagnosed by a symptom report by patients and signs as assessed by study physicians. Chronic diarrhea was defined as a patient report of diarrhea for ≥14 d. Pulmonary tuberculosis was diagnosed according to Tanzanian National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Program guidelines. Participants with symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis were asked to provide the following 3 sputum samples: a spot sputum specimen at the study visit at which symptoms were first reported, an early morning sputum before a second clinic visit the next day, and a third sputum specimen at the second clinic visit. Participants were diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis if at least one of the 3 sputum smears was positive for acid-fast bacilli by using Ziehl-Nielsen staining or when a chest X-ray exhibited radiologic features consistent with tuberculosis when all sputum smears were negative for acid-fast bacilli (14). The absolute CD4 T cell count and a complete blood count were assessed at clinic visits every 4 mo.

Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the parent trial. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the Harvard School of Public Health, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Tanzania Food and Drug Authority, and the Tanzanian National Institute of Medical Research.

Statistics

BMI at ART initiation was defined as moderate-to-severe malnutrition (<17.0), mild malnutrition (≥17.0 and <18.5), normal (≥18.5 and <25.0), and overweight or obese (≥25) categories. Cox proportional hazard models were used to examine the association of baseline BMI with mortality and the incidence of morbidities (15). P-trend values were calculated by treating the median value of each baseline BMI category as a continuous variable. Individuals who experienced morbidity events of interest at ART initiation were excluded from baseline BMI analyses. Individuals without events were censored at the date of the last follow-up visit, and proportionality assumptions of Cox models were verified by using time-by-variable interaction terms.

The association of baseline BMI with the change in CD4 T cell count over time was analyzed by using generalized estimating equations. An m-dependent working correlation matrix (m = 1) was used in models, which assumed the correlation coefficient of adjacent observations were nonzero and equal. Robust estimators of variances, which are consistent estimators even if the working correlation matrix is misspecified, were used to construct CIs. The potential nonlinear relation of change in CD4 T cell counts between consecutive clinic visits over time was assessed nonparametrically with restricted cubic splines for the time since ART initiation (16, 17). If a nonlinear relation was shown, we added the selected cubic-spline terms to the model as covariates. To assess the association of the baseline and change in CD4 T cell counts between consecutive visits over time, we included the interactions of baseline BMI category with time since ART initiation and its splines. The robust score test was used to determine whether the CD4 T cell trajectory differed by baseline BMI category. The baseline CD4 T cell count was not adjusted for in this analysis because of risk of bias when modeling the change over time (18).

Weight change after 1 mo of ART was grouped into categories of ≥2.5% weight loss, 0–2.5% weight loss, 0–2.5% weight gain, and ≥2.5% weight gain on the basis of the distribution of weight change for the cohort. Previous studies have used 5% weight-change categories after 3 mo of ART (9, 10), but very few individuals in our study experienced ≥5% weight loss by 1 mo of ART initiation (4%). Cox proportional hazard models were used to examine the association of weight change after 1 mo of ART with mortality and the incidence of morbidities (15). P-trend values were calculated by treating the median value of each weight-change category as a continuous variable in the proportional hazards models. The relation of weight change as a continuous variable and mortality was also analyzed. The possible nonlinear relation between a continuous weight change and mortality was examined nonparametrically with restricted cubic splines (16, 17). Tests for nonlinearity used the likelihood ratio test and compared the model with only the linear term to the model with the linear and cubic spline terms. All individuals with the mortality or morbidity event of interest before 1 mo (35 d) were excluded from weight-change analyses.

To assess whether associations of weight change at 1 mo of ART with mortality and morbidity outcomes significantly varied by baseline BMI, we used interaction terms of weight-change categories and baseline BMI categories with the use of the likelihood ratio test to assess the statistical significance. We also investigated interactions by dichotomizing weight change as any weight loss (<0% change) and maintenance or weight gain (≥0%) and also decreasing baseline BMI categories to 3 categories (<18.5, ≥18.5 and <25.0, and ≥25) to increase the statistical power of tests for interaction. If the association of weight change with mortality or morbidity outcomes significantly differed across strata of BMI at ART initiation, we used proportional hazard models and assessed effect modification stratified by baseline BMI. Potential effect modifiers included demographics (sex and age), markers of HIV disease severity (WHO HIV stage, CD4 T cell count, and hemoglobin concentration), indicators of exposure to opportunistic pathogens (district, educational attainment, household assets, and season of ART initiation), ART regimen, randomized multivitamin regimen, and timing of the 1-mo clinic visit. These effect modifiers were selected as an attempt to capture the multifactorial causes of weight loss for HIV-infected adults (eg, malabsorption, decreased caloric intake, comorbidities, and hypermetabolism), which alone or in combination may vary in association with HIV progression (19).

The association of weight change after 1 mo of ART with CD4 T cell count over time was also analyzed by using generalized estimating equations, similar to the analysis of baseline BMI with the change in CD4 T cell count. An m-dependent working correlation matrix (m = 1) was used, and robust estimators were used to construct CIs. The potential nonlinear relation of change in CD4 T cell counts between consecutive clinic visits over time was assessed nonparametrically with restricted cubic splines for the time since ART initiation (16, 17). The robust score test was used to determine whether the CD4 T cell trajectory differed by category of weight change after 1 mo of ART or baseline BMI category.

Confounders in multivariate analyses included baseline demographic, socioeconomic, HIV disease severity, randomized multivitamin, and seasonality variables, which have been shown to be associated with both nutritional status and HIV progression in the literature (19–21). The following variables and categorizations were included in multivariate models: sex, age (<30, 30–39, 40–49, or ≥50 y), district (Ilala, Kinondoni, or Temeke), highest attained education (none/primary or secondary/advanced), number of household assets (0–1, 2–3, or 4–5), season of ART initiation [long rain (December to March), harvest (April to May), postharvest (June to August), and short rain (September to November)], randomized multivitamin regimen (single RDA or multiple RDA), baseline CD4 T cell count (<50, 50–99, 100–199, or ≥200 cells/μL), baseline hemoglobin concentration (<8.5, ≥8.5 and <11, or ≥11 g/dL), baseline WHO HIV stage (I/II, III, or IV), baseline oral candidiasis, baseline diagnosis or receipt of pulmonary tuberculosis treatment, and ART regimen (stavudine-lamivudine-nevirapine, stavudine-lamivudine-efavirenz, zidovudine-lamivudine-nevirapine, or zidovudine-lamivudine-efavirenz regimens). Missing data for covariates were retained in analyses by using the missing indicator method (22). All P values were 2 sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS v 9.2 software (SAS Institute Inc).

RESULTS

Characteristics of individuals with baseline BMI measurements

The parent trial enrolled 3418 adults initiating ART, and 3389 (99.2%) of these individuals had their BMI measured at the baseline clinic visit. The proportion of subjects with a BMI <17 at ART initiation was 12.5%, 14.8% of subjects had a BMI ≥17.0 and <18.5, 57.8% of subjects had a BMI ≥18.5 and <25.0, and 14.9% of subjects had a baseline BMI ≥25.0. Baseline characteristics of study participants with BMI measurements at ART initiation are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study cohort at ART initiation for participants with baseline BMI measured (n = 3389) and participants with weight-change data at 1 mo (n = 2255)1

| Characteristics | Baseline BMI measured (n = 3389) | Weight measured at 1 mo (n = 2255) |

| Sex (F) [n (%)] | 2303 (68.0) | 1581 (70.1) |

| Age category [n (%)] | ||

| <30 y | 519 (15.3) | 344 (15.3) |

| 30–39 y | 1642 (48.5) | 1091 (48.4) |

| 40–50 y | 901 (26.6) | 601 (26.7) |

| >50 y | 327 (9.7) | 219 (9.71) |

| District [n (%)] | ||

| Ilala | 1339 (43.1) | 912 (44.5) |

| Kinondoni | 947 (30.4) | 674 (32.9) |

| Temeke | 821 (26.4) | 491 (23.6) |

| Highest attained education [n (%)] | ||

| None/primary | 1527 (45.1) | 1154 (51.2) |

| Secondary/advanced | 957 (28.2) | 679 (30.1) |

| Missing | 905 (26.7) | 422 (18.7) |

| No. of household assets owned [n (%)]2 | ||

| 0–1 | 598 (17.7) | 441 (19.6) |

| 2–3 | 1009 (29.8) | 733 (32.5) |

| 4–5 | 925 (27.3) | 694 (30.8) |

| Missing | 857 (25.3) | 387 (17.2) |

| BMI category [n (%)] | ||

| <17.0 kg/m2 | 422 (12.5) | 270 (12.0) |

| ≥17.0 and <18.5 kg/m2 | 503 (14.8) | 324 (14.4) |

| ≥18.5 and <25.0 kg/m2 | 1959 (57.8) | 1316 (58.4) |

| ≥25.0 kg/m2 | 505 (14.9) | 345 (15.3) |

| WHO HIV disease-stage category [n (%)] | ||

| I or II | 694 (22.3) | 477 (22.9) |

| III | 1972 (63.5) | 1325 (63.6) |

| IV | 441 (14.2) | 282 (13.5) |

| CD4 T cell category [n (%)] | ||

| <50 cells/μL | 735 (22.6) | 451 (20.8) |

| 50–99 cells/μL | 629 (19.3) | 426 (19.6) |

| 100–200 cells/μL | 1220 (37.5) | 852 (39.2) |

| >200 cells/μL | 669 (20.6) | 443 (20.4) |

| Hemoglobin category [n (%)] | ||

| <8.5 g/dL | 708 (22.0) | 462 (21.5) |

| ≥8.5 and <11 g/dL | 1376 (42.8) | 920 (42.9) |

| ≥11 g/dL | 1128 (35.1) | 764 (35.7) |

| Chronic diarrhea [n (%)] | 67 (2.0) | 51 (2.3) |

| Oral candidiasis [n (%)] | 213 (6.3) | 147 (6.5) |

| Tuberculosis treatment and diagnosis [n (%)] | 317 (9.4) | 234 (10.4) |

| ART regimen [n (%)] | ||

| Stavudine, lamivudine, nevirapine | 1975 (58.3) | 1267 (56.2) |

| Stavudine, lamivudine, efavirenz | 349 (10.3) | 232 (10.3) |

| Zidovudine, lamivudine, nevirapine | 275 (8.1) | 206 (9.1) |

| Zidovudine, lamivudine, efavirenz | 790 (23.3) | 550 (24.4) |

ART, antiretroviral therapy.

From a list that included a sofa, television, radio, refrigerator, and fan. ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Baseline BMI and mortality

Participants were prospectively followed at monthly clinic visits, and the median follow-up time was 19.7 mo (IQR: 8.3–31.5 mo). A total of 445 deaths (13.1% cumulative incidence) were prospectively recorded in individuals with a baseline BMI measurement. A total of 31.0% of total deaths occurred at <1 mo of ART (n = 138), 28.5% of total deaths (n = 127) occurred at 1–3 mo of ART, and 40.5% of total deaths (n = 445) occurred after 3 mo of ART. Associations of baseline BMI with mortality are shown in Table 2. Lower BMI at ART initiation was significantly associated with an increased hazard of mortality (P-trend < 0.001). There was no indication of effect modification of the baseline BMI and mortality association by any baseline covariate, and associations did not change over time.

TABLE 2.

Univariate and multivariate HRs for all-cause mortality and incident morbidities by BMI (in kg/m2) at ART initiation (n = 3389)1

| BMI |

|||||

| Outcome (no. of events) | <17.0 kg/m2 (n = 422) | ≥17.0 and <18.5 (n = 503) | ≥18.5 and <25.0 (n = 1959) | ≥25.0 (n = 505) | P- trend |

| Death (439) | |||||

| Univariate | 3.24 (2.57, 4.07) | 2.00 (1.56, 2.56) | 1.0 (reference) | 0.75 (0.53, 1.06) | <0.001 |

| Multivariate | 1.91 (1.47, 2.49) | 1.51 (1.15, 1.98) | 1.0 (reference) | 0.93 (0.68, 1.43) | <0.001 |

| URTI (995) | |||||

| Univariate | 1.02 (0.83, 1.25) | 1.02 (0.85, 1.23) | 1.0 (reference) | 0.85 (0.71, 1.02) | 0.081 |

| Multivariate | 0.93 (0.75, 1.16) | 1.01 (0.83, 1.22) | 1.0 (reference) | 0.85 (0.70, 1.03) | 0.260 |

| Pneumonia (970) | |||||

| Univariate | 1.31 (1.07, 1.59) | 1.04 (0.86, 1.25) | 1.0 (reference) | 0.90 (0.75, 1.08) | 0.009 |

| Multivariate | 1.19 (0.97, 1.46) | 0.98 (0.81, 1.19) | 1.0 (reference) | 0.96 (0.79, 1.16) | 0.241 |

| Oral thrush (379) | |||||

| Univariate | 1.74 (1.32, 2.29) | 1.21 (0.91, 1.62) | 1.0 (reference) | 0.74 (0.53, 1.03) | <0.001 |

| Multivariate | 1.31 (0.97, 1.76) | 1.05 (0.78, 1.41) | 1.0 (reference) | 0.77 (0.55, 1.09) | 0.018 |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis (147) | |||||

| Univariate | 1.42 (0.88, 2.29) | 1.70 (1.13, 2.55) | 1.0 (reference) | 0.48 (0.26, 0.90) | <0.001 |

| Multivariate | 1.02 (0.61, 1.72) | 1.37 (0.88, 2.13) | 1.0 (reference) | 0.58 (0.31, 1.11) | 0.063 |

| Chronic diarrhea (111) | |||||

| Univariate | 0.89 (0.46, 1.73) | 1.31 (0.79, 2.19) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.12 (0.67, 1.87) | 0.891 |

| Multivariate | 0.54 (0.29, 1.00) | 0.85 (0.51, 1.42) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.02 (0.61, 1.71) | 0.144 |

| Kaposi sarcoma (70) | |||||

| Univariate | 0.90 (0.40, 2.00) | 0.80 (0.38, 1.71) | 1.0 (reference) | 1.04 (0.55, 1.96) | 0.637 |

| Multivariate | 0.59 (0.25, 1.40) | 0.57 (0.26, 1.25) | 1.0 (reference) | 0.98 (0.47, 2.01) | 0.213 |

| EPTB (56) | |||||

| Univariate | 0.58 (0.21, 1.65) | 1.81 (0.36, 1.80) | 1.0 (reference) | 0.68 (0.30, 1.52) | 0.959 |

| Multivariate | 0.33 (0.09, 1.16) | 0.78 (0.34, 1.80) | 1.0 (reference) | 0.79 (0.33, 1.90) | 0.426 |

All values are HRs; 95% CIs in parentheses. The analysis was adjusted for randomized regimen, sex, age, district, educational attainment, household assets, hemoglobin, WHO HIV stage, oral candidiasis, tuberculosis treatment and diagnosis, chronic diarrhea, ART regimen, and season of ART initiation. Individuals diagnosed with events at the ART initiation visit were excluded. ART, antiretroviral therapy; EPTB, extrapulmonary tuberculosis; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection.

Baseline BMI and morbidity

Associations of baseline BMI with incident morbidities are shown in Table 2. Baseline BMI was significantly associated with the incidence of oral thrush (P-trend = 0.018). There was also some indication of increased risk of incident pulmonary tuberculosis with lower baseline BMI, but results were not statistically significant (P-trend = 0.063). There was no indication of effect modification of any baseline BMI and morbidity association by any baseline covariate, and associations did not change over time.

Baseline BMI and CD4 T cell count

CD4 T cell counts were assessed every 4 mo, and 2688 individuals had ≥2 CD4 T cell–count observations. Participants, regardless of baseline BMI, experienced dramatic increases in CD4 T cell counts during the first 6 mo of ART (mean increase: 28.3 cells/mo) with more modest gains after 6 mo (mean increase: 5.8 cells/mo). There was no significant difference in CD4 T cell trajectory in individuals with a baseline BMI <17 (P = 0.708) or ≥17.0 and <18.5 (P = 0.232) in comparison with individuals with a baseline BMI ≥18.5 and <25.0 with multivariate adjustment. There was some indication that individuals with a baseline BMI ≥25.0 may have hastened CD4 T cell recovery compared with subjects with a baseline BMI ≥18.5 and <25.0, but the difference in trajectory was not statistically significant (P = 0.066).

Characteristics of individuals with weight-change measurements

A total of 2255 (66.5%) adults with a baseline BMI measurement also had their weights measured at a 1-mo clinic visit (20–35 d). Baseline characteristics of study participants with weight-change data at 1 mo are also presented in Table 1. The median weight change at 1 mo of ART was +1.0 kg (IQR: −0.3 to +2.4 kg) or +2.0% (IQR: −0.4% to +4.6%). The proportion of participants who experienced ≥2.5% weight loss at 1 mo of ART was 13.7%, 12.3% of individuals had 0–2.5% weight loss, 31.1% of subjects had a weight gain of 0–2.5%, and 42.9% of subjects experienced weight gains ≥2.5%. The primary reason for participants not having weight-change data at 1 mo was that the participant was seen at a clinic visit that occurred after 35 d (29.3%). There was no significant difference in any baseline characteristic between individuals with weight-change data at 1 mo and participants who attended a clinic visit that occurred after 35 d.

Weight change and mortality

A total of 195 deaths (8.6% cumulative incidence) occurred after 1 mo of ART in individuals with weight-change data. We found a significant multiplicative interaction between any weight loss (<0% change) at 1 mo of ART and baseline BMI in 3 categories (<18.5, ≥18.5 and <25.0, and ≥25) (P-interaction = 0.011). In individuals with a baseline BMI <18.5, any weight loss was associated with 5.40 times (95% CI: 3.45, 8.46 times; P < 0.001) the hazard of mortality in comparison with subjects who maintained or gained weight after multivariate adjustment. In contrast, any weight loss was associated with 2.15 times (95% CI: 1.37, 3.38 times; P < 0.001) and 2.68 times (95% CI: 0.66, 10.82 times; P = 0.166) the hazard of mortality in individuals with a baseline BMI ≥18.5 and <25.0 and >25.0, respectively.

Univariate and multivariate associations of weight change by the original 4 categories of weight change at 1 mo and mortality are presented in Table 3 stratified by baseline BMI. There was a significant mortality trend for individuals who lost weight or gained <2.5% compared with subjects who had ≥2.5% weight gains for all strata of baseline BMI <25 (P-trend < 0.001). Participants who experienced ≥2.5% weight loss had 6.43 times (95% CI: 3.78, 10.93 times) the hazard of mortality as participants with weight gains ≥2.5% if their baseline BMI was <18.5 but only 2.73 times (95% CI: 1.49, 5.00 times) the hazard of mortality if their baseline BMI was ≥18.5 and <25.0. The mortality trend for weight change was borderline significant for individuals with a baseline BMI ≥25 (P-trend = 0.056). Nevertheless, weight loss of ≥2.5% was significantly associated with increased risk of mortality compared with a weight gain of ≥2.5% in individuals with a baseline BMI ≥25 (HR: 6.81; 95% CI: 1.05, 44.23; P = 0.044).

TABLE 3.

Univariate and multivariate associations of weight change at 1 mo after ART initiation and mortality stratified by baseline BMI1

| Baseline BMI | No. of deaths | No. of participants | Univariate HR (95% CI) | P-trend | Multivariate HR (95% CI) | P-trend |

| <18.5 kg/m2 | ||||||

| ≥2.5% weight loss | 42 | 104 | 5.87 (2.94, 11.71) | <0.001 | 6.43 (3.78, 10.93) | <0.001 |

| 0–2.5% weight loss | 14 | 55 | 3.34 (1.35, 8.27) | 3.97 (2.01, 7.83) | ||

| 0–2.5% weight gain | 10 | 110 | 0.87 (0.29, 2.64) | 0.79 (0.37, 1.73) | ||

| ≥2.5% weight gain | 31 | 325 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||

| ≥18.5 and <25.0 kg/m2 | ||||||

| ≥2.5% weight loss | 24 | 167 | 3.88 (2.18, 6.93) | <0.001 | 2.73 (1.49, 5.00) | <0.001 |

| 0–2.5% weight loss | 13 | 168 | 2.03 (1.02, 4.03) | 2.43 (1.20, 4.94) | ||

| 0–2.5% weight gain | 24 | 431 | 1.42 (0.80, 2.53) | 1.46 (0.80, 2.66) | ||

| ≥2.5% weight gain | 22 | 550 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) | ||

| ≥25.0 kg/m2 | ||||||

| ≥2.5% weight loss | 5 | 37 | 4.54 (1.09, 19.02) | 0.829 | 6.81 (1.05, 44.2) | 0.056 |

| 0–2.5% weight loss | 1 | 54 | 0.58 (0.06, 5.58) | 0.89 (0.08, 10.12) | ||

| 0–2.5% weight gain | 6 | 161 | 1.16 (0.29, 4.66) | 1.90 (0.34, 10.77) | ||

| ≥2.5% weight gain | 3 | 93 | 1.0 (Ref) | 1.0 (Ref) |

Adjusted for randomized regimen, sex, age, district, educational attainment, household assets, hemoglobin, WHO HIV stage, oral candidiasis, tuberculosis treatment and diagnosis, chronic diarrhea, ART regimen, and season of ART initiation. ART, antiretroviral therapy; Ref, reference.

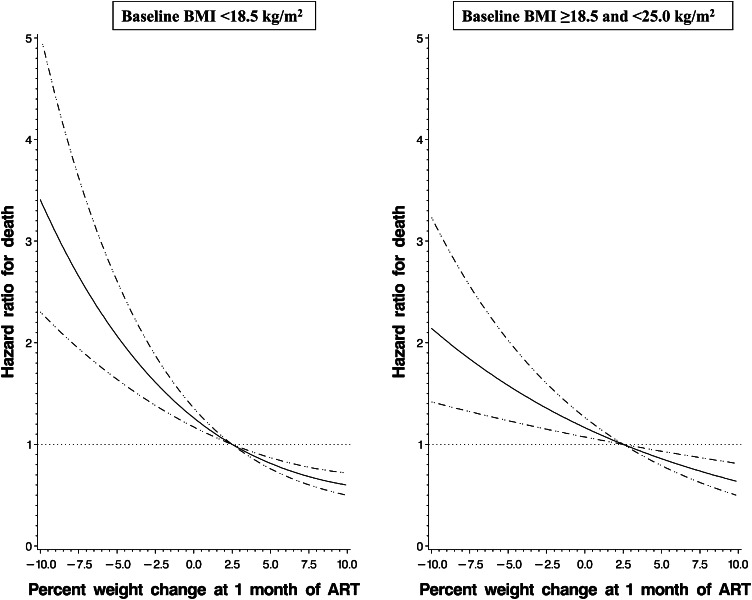

We also analyzed the relation between weight change at 1 mo and mortality continuously stratified by BMI at ART initiation. The relation of weight change with mortality was shown to be significantly nonlinear for individuals with a baseline BMI <18.5 (P-nonlinear relation = 0.008). In contrast, weight change was linearly associated with mortality for individuals with a baseline BMI ≥18.5 and <25.0 (P-linear relation < 0.001) and for subjects with a baseline BMI ≥25 (P-linear relation = 0.023). The continuous relation of weight change and mortality in individuals with a baseline BMI <18.5 and for subjects with a baseline BMI ≥18.5 and <25.0 is shown in Figure 1. A comparison of the shape of relations presented in Figure 1 showed that the magnitude of the mortality association was incrementally greater as weight loss increased for malnourished adults compared with adults with a normal BMI at ART initiation.

FIGURE 1.

Relation between the percentage of weight change at 1 mo of ART and mortality for individuals with baseline BMI (in kg/m2) <18.5 (left graph) and ≥18.5 and <25.0 (right graph) after multivariate adjustment (adjusted for randomized regimen, sex, age, district, educational attainment, household assets, hemoglobin, WHO HIV stage, oral candidiasis, tuberculosis treatment and diagnosis, chronic diarrhea, ART regimen, and season of ART initiation). The solid line shows the estimated HR of mortality for the percentage of weight change relative to the reference weight change of +2.5%, and the horizontal dotted line designates the null HR of 1.0. Dashed lines denote 95% CIs of the HR. The relation was significantly nonlinear for individuals with a baseline BMI <18.5 (P-nonlinear relation = 0.008) and was significantly linear for patients with a baseline BMI ≥18.5 and <25.0 (P-linear relation < 0.001). ART, antiretroviral therapy.

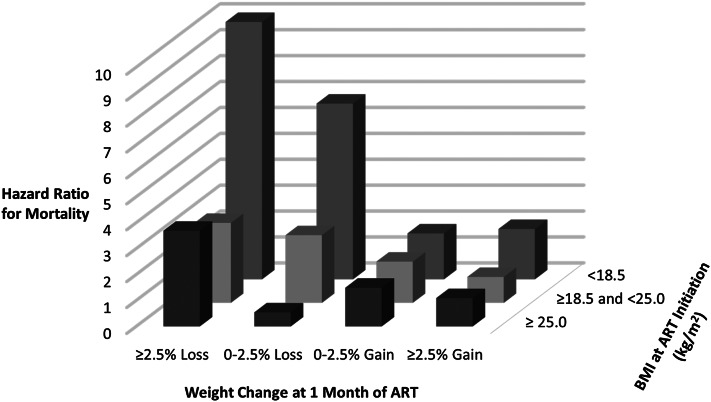

The combined association of baseline BMI and weight change at 1 mo of ART on mortality is shown in Figure 2. Participants with a baseline BMI <18.5 who experienced ≥2.5% weight loss at 1 mo of ART had a 10-fold increase in risk of subsequent mortality in comparison with individuals with a baseline BMI ≥18.5 and <25.0 who had weight gains ≥2.5% (HR: 9.93; 95% CI: 5.68, 17.32; P < 0.001). There was no indication of effect modification of the weight change and mortality relation by sex, age, district, education, asset group, randomized multivitamin regimen, ART regimen, WHO HIV disease stage, CD4 T cell count, hemoglobin concentration, or timing of the 1-mo study visit within strata of baseline BMI. There was also no indication that HRs for mortality changed over time within strata of baseline BMI.

FIGURE 2.

Multivariate (adjusted for randomized regimen, sex, age, district, educational attainment, household assets, hemoglobin, WHO HIV stage, oral candidiasis, tuberculosis treatment and diagnosis, chronic diarrhea, ART regimen, and season of ART initiation) joint association of baseline BMI (in kg/m2) and weight change after 1 mo of ART on the hazard of mortality with a BMI of 18.5–25.0 and ≥2.5% weight gain as the reference. ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Weight change and morbidity

Relations of weight change at 1 mo of ART with the incidence of morbidities after 1 mo of treatment are presented in Table 4. After multivariate adjustment, there was a significant trend of increasing hazard of pneumonia (P = 0.002), oral thrush (P = 0.007), and pulmonary tuberculosis (P < 0.001) for individuals who lost weight or gained <2.5% of weight as compared with individuals with weight gains ≥2.5%. We showed no indication of effect modification of weight change and morbidity associations by baseline BMI, other baseline covariates, or timing of the 1-mo visit.

TABLE 4.

Univariate and multivariate associations of weight change at 1 mo of ART and incidence of morbidities after 1 mo of treatment (n = 2255)1

| Outcome (no. of events) | ≥2.5% weight gain (n = 309) (reference) | 0–2.5% weight gain (n = 277) | 0–2.5% weight loss (n = 701) | ≥2.5% weight loss (n = 968) | P-trend |

| URTI (780) | |||||

| Univariate | 1.0 (reference) | 0.82 (0.70, 0.97) | 0.89 (0.71, 1.12) | 1.06 (0.85, 1.32) | 0.727 |

| Multivariate | 1.0 (reference) | 0.85 (0.72, 1.02) | 0.95 (0.74, 1.21) | 1.04 (0.83, 1.30) | 0.870 |

| Pneumonia (774) | |||||

| Univariate | 1.0 (reference) | 0.92 (0.78, 1.08) | 1.02 (0.81, 1.29) | 1.40 (1.13, 1.74) | 0.019 |

| Multivariate | 1.0 (reference) | 0.97 (0.81, 1.16) | 1.09 (0.85, 1.41) | 1.53 (1.22, 1.91) | 0.002 |

| Oral thrush (213) | |||||

| Univariate | 1.0 (reference) | 0.97 (0.69, 1.35) | 1.51 (1.01, 2.28) | 1.86 (1.27, 2.71) | 0.001 |

| Multivariate | 1.0 (reference) | 1.07 (0.75, 1.51) | 1.65 (1.08, 2.51) | 1.64 (1.10, 2.43) | 0.007 |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis (83) | |||||

| Univariate | 1.0 (reference) | 1.77 (1.05, 3.00) | 1.04 (0.45, 2.41) | 3.17 (1.76, 5.71) | <0.001 |

| Multivariate | 1.0 (reference) | 1.74 (0.98, 3.09) | 1.23 (0.52, 2.93) | 3.18 (1.73, 5.84) | <0.001 |

| Chronic diarrhea (90) | |||||

| Univariate | 1.0 (reference) | 0.72 (0.43, 1.21) | 0.95 (0.47, 1.91) | 1.33 (0.74, 2.51) | 0.569 |

| Multivariate | 1.0 (reference) | 0.77 (0.45, 1.33) | 1.19 (0.59, 2.38) | 1.67 (0.91, 3.08) | 0.174 |

| Kaposi sarcoma (54) | |||||

| Univariate | 1.0 (reference) | 1.48 (0.81, 2.68) | 0.52 (0.16, 1.75) | 1.40 (0.62, 3.16) | 0.572 |

| Multivariate | 1.0 (reference) | 1.85 (0.97, 3.52) | 0.57 (0.17, 1.97) | 1.67 (0.72, 3.38) | 0.314 |

| EPTB (42) | |||||

| Univariate | 1.0 (reference) | 1.14 (0.55, 2.37) | 0.93 (0.31, 2.79) | 2.10 (0.93, 4.76) | 0.126 |

| Multivariate | 1.0 (reference) | 1.01 (0.44, 2.28) | 0.92 (0.28, 3.03) | 2.59 (1.10, 6.11) | 0.065 |

All values are HRs; 95% CIs in parentheses. Adjusted for baseline BMI, randomized regimen, sex, age, district, educational attainment, household assets, hemoglobin concentration, WHO HIV stage, oral candidiasis, tuberculosis treatment and diagnosis, chronic diarrhea, ART regimen, and season of ART initiation. Individuals with events occurring at or before the 1-mo visit were excluded. ART, antiretroviral therapy; EPTB, extrapulmonary tuberculosis; URTI, upper respiratory tract infection.

Weight change and CD4 T cell count

We also examined the association of weight change at 1 mo of ART with the change in CD4 T cell count over time. After multivariate adjustment, there was no significant difference in the CD4 T cell trajectory for individuals with ≥2.5% weight loss (P = 0.782), 0–2.5% weight loss (P = 0.401), or 0–2.5% weight gain (P = 0.490) in comparison with individuals who experienced weight gain ≥2.5%. There was also no significant difference in the change in CD4 T cell count for individuals with any weight loss at 1 mo in comparison with individuals who maintained or gained weight after multivariate adjustment (P = 0.173).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that low BMI at ART initiation and weight loss after 1 mo of treatment were independently associated with subsequent mortality in HIV-infected adults in Tanzania. In addition, the magnitude of the weight-loss association significantly varied across strata of baseline BMI. Weight loss at 1 mo of ART was also significantly associated with the incidence of pneumonia, oral thrush, and pulmonary tuberculosis but not change in CD4 T cell count.

Our results confirmed previous studies that showed weight loss was a strong independent predictor of mortality in HIV-infected individuals receiving ART, but we contributed that weight loss as early as 1 mo after ART initiation can identify adults at high risk of mortality (8–10). To our knowledge, this was also the first study to report a significant multiplicative interaction of weight loss and mortality associations by baseline BMI. In a cohort study of 18,271 adults initiating ART in the Management and Development for Health President's Plan for AIDS Relief treatment program in Tanzania, weight loss at 3 mo was significantly associated with increased risk of death within all levels of baseline BMI, with the highest risk of death in individuals with a baseline BMI <17.0 (P-interaction = 0.09) (10). All adults in our study were also included in this previous Tanzanian cohort study; however, data on weight change at 1 mo of ART as well as morbidity data were not available. As a result, we used adults enrolled in a multivitamin clinical trial conducted in Management and Development for Health President's Plan for AIDS Relief to obtain these data. Even though our study had a considerably smaller sample size than the previous study, there may have been less measurement error in weight changes and the misclassification of outcomes and confounding variables because participants were seen more frequently by trained research nurses and tracked at home if they missed a clinic visit.

There are numerous potential mechanisms that may explain the association of weight loss with increased mortality in HIV-infected individuals initiating ART because malnutrition can directly or indirectly interfere with the proper functioning of virtually all organ systems (23). Protein-calorie malnutrition can have deleterious effects on both antigen and cell-mediated immune responses, including reduced lymphocyte counts, the induction of generalized proinflammatory responses, and reduced bactericidal activity (24, 25). As a result, individuals with protein-calorie malnutrition have been well documented to have an increased incidence and severity of life-threatening opportunistic infections (26, 27). In this study, we showed low baseline BMI was associated with increased incidence of oral thrush, and weight change at 1 mo of treatment was associated with the incidence of oral thrush, pneumonia, and pulmonary tuberculosis.

Individuals who are undernourished are also at high risk of micronutrient deficiency (28, 29). Consequently, low baseline BMI or weight loss in our study may have been a surrogate for micronutrient deficiency; however, all study participants were provided with daily multivitamins that contained at least single RDAs of vitamins B complex, C, and E. Accordingly, all individuals in the study likely experienced the benefits of vitamin B complex, C, and E supplements on mortality and CD4 T cell reconstitution (11). Nevertheless, we could not rule out that BMI was a surrogate for micronutrients that were not contained in the multivitamin supplement, such as zinc for which preventive supplementation has been shown to decrease risk of pneumonia and diarrhea in children (30). There has also been some evidence that ART programs that incorporate macronutrient supplementation have increased medication adherence, and as a result, our findings may have been partially a surrogate for treatment compliance (31, 32). In addition, food insecurity may contribute to the association of baseline BMI and weight change with morbidity and mortality thorough multiple mechanisms including reduced physical and mental health (33), reduced use of health care services as a tradeoff for obtaining food (34), and lower ART adherence (35).

Mortality and morbidity in HIV-infected individuals may also be reduced if CD4 T cell reconstitution is accelerated; however, we did not find any significant association of baseline BMI or weight change at 1 mo of treatment with the change in CD4 T cell count over time. Studies conducted in Zambia, Cote d'Ivoire, and Singapore also showed no association of low baseline BMI with the change in CD4 T cell count (7, 36, 37). In contrast, a study of adults initiating ART in the United States showed significantly greater CD4 T cell increases after 12 mo of ART for individuals with a baseline BMI of 25–30 compared with individuals with a baseline BMI <25 (38). Our study, as well as previous studies in resource-limited settings, may have had limited power to detect a moderate difference in the rate of CD4 T cell–count change by BMI because of the low prevalence of participants with a BMI >25.

The sum of our mortality and morbidity findings suggested that providing nutritional interventions to HIV-infected adults at ART initiation may improve survival and quality of life. Macronutrient supplementation is recommended by the WHO and is currently integrated into many ART programs in resource-limited settings, but few studies have assessed the effect of supplementation on treatment outcomes (39, 40). A study conducted in Zambia showed that individuals who received food from the World Food Program had increased ART adherence than did individuals who did not receive World Food Program food, but there was no significant difference in mortality, CD4 T cell reconstitution, or weight gain (31). A recent prospective interventional study in India also showed no significant difference in weight gain or CD4 T cell count for HIV-infected adults who received oral macronutrient supplements compared with the standard of care (41). To establish the utility and optimize potential benefits of integrating macronutrient interventions into HIV programs, future studies are needed to determine the effectiveness of macronutrient supplementation and the optimal composition of supplements (42).

There were a few limitations to this study. First, participants did not receive routine HIV viral load monitoring, which may have confounded our results. Nevertheless, routine HIV viral load assessment is not currently included in national guidelines for many resource-limited countries because of the high cost of testing and other logistical difficulties (43). We also adjusted for other markers of disease severity in the analysis, including the CD4 T cell count, WHO HIV stage, oral candidiasis, tuberculosis treatment and diagnosis, and chronic diarrhea. Second, only 20% of the sample had baseline CD4 T cell counts >200 cells/μL, and as result, we may not have had adequate statistical power to detect the effect modification of any association for individuals with CD4 T cell counts >200 cells/μL at ART initiation. Third, we did not have data on changes in body composition and fat distribution during the study period. Consequently, we could not differentiate individuals who experienced a loss of lean body mass from individuals who experienced lipoatrophy (44). Future studies of changes in body composition and fat distribution after ART initiation are needed to refine associations.

In conclusion, we showed that weight loss at 1 mo of ART was associated with mortality with significant variation in the magnitude by BMI at ART initiation. Although there are numerous potential explanations for our findings, the clinical utility of being able to identify patients at high risk of adverse events through low-cost point-of-care monitoring of nutritional status and weight change is not diminished by the causal uncertainty. These findings may be particularly useful in settings where regular laboratory testing of CD4 T cell counts and HIV viral loads are limited or nonexistent. Future studies identifying and managing sources of early weight loss or weight-gain restriction are needed to provide better HIV care in resource-limited settings.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants and field teams, including physicians, nurses, supervisors, laboratory staff, and administrative staff who made the study possible and the Muhimbili National Hospital, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Dar es Salaam City and the Municipal Medical Offices of Health, and the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare for their institutional support and guidance.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—CRS, SI, FMM, GEC, ELG, and WWF: designed the research; FMM, SA, and WWF: conducted the research; CRS and MW: analyzed data; CRS: wrote the manuscript; CRS and WWF: had primary responsibility for the final content of the manuscript; and all authors: contributed to and approved the final manuscript. None of the authors had a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization Epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braitstein P, Brinkhof MW, Dabis F, Schechter M, Boulle A, Miotti P, Wood R, Laurent C, Sprinz E, Seyler C, et al. Mortality of HIV-1 infected patients in the first year of antiretroviral therapy: comparison between low-income and high-income countries. Lancet 2006;367:817–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu G, Zaman MH. Low-cost tools for diagnosing and monitoring HIV infection in low-resource settings. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:914–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koethe JR, Chi BH, Megazzini KM, Heimburger DC, Stringer JS. Macronutrient supplementation for malnourished HIV-infected adults: a review of the evidence in resource-adequate and resource-constrained settings. Clin Infect Dis 2009;49:787–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moh R, Danel C, Messou E, Ouassa T, Gabillard D, Anzian A, Abo Y, Salamon R, Bissagnene E, Seyler C, et al. Incidence and determinants of mortality and morbidity following early antiretroviral therapy initiation in HIV-infected adults in West Africa. AIDS 2007;21:2483–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sieleunou I, Souleymanou M, Schonenberger AM, Menten J, Boelaert M. Determinants of survival in AIDS patients on antiretroviral therapy in a rural centre in the Far-North Province, Cameroon. Trop Med Int Health 2009;14:36–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paton NI, Sangeetha S, Earnest A, Bellamy R. The impact of malnutrition on survival and the CD4 count response in HIV-infected patients starting antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med 2006;7:323–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koethe JR, Lukusa A, Giganti MJ, Chi BH, Nyirenda CK, Limbada MI, Banda Y, Stringer JS. Association between weight gain and clinical outcomes among malnourished adults initiating antiretroviral therapy in Lusaka, Zambia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010;53:507–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Madec Y, Szumilin E, Genevier C, Ferradini L, Balkan S, Pujades M, Fontanet A. Weight gain at 3 months of antiretroviral therapy is strongly associated with survival: evidence from two developing countries. AIDS 2009;23:853–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu E, Spiegelman D, Semu H, Hawkins C, Chalamilla G, Aveika A, Nyamsangia S, Mehta S, Mtasiwa D, Fawzi W. Nutritional status and mortality among HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania. J Infect Dis 2011;204:282–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zachariah R, Fitzgerald M, Massaquoi M, Pasulani O, Arnould L, Makombe S, Harries AD. Risk factors for high early mortality in patients on antiretroviral treatment in a rural district of Malawi. AIDS 2006;20:2355–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isanaka S, Mugusi F, Hawkins C, Spiegelman D, Okuma J, Aboud S, Guerino C, Fawzi WW. Effect of high-dose multivitamin supplementation at the initiation of HAART on HIV disease progression and mortality in Tanzania: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2012;308:1535–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization Scaling up antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings: treatment guidelines for a public health approach. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enarson DA, Rieder HL, Arnadottir T, Trébucq A. Management of tuberculosis. A guide for low income countries. 5th ed. Paris, France: International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cox D. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc [Ser A] 1972;34:187–220 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durrleman S, Simon R. Flexible regression models with cubic splines. Stat Med 1989;8:551–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Govindarajulu US, Spiegelman D, Thurston SW, Ganguli B, Eisen EA. Comparing smoothing techniques in Cox models for exposure-response relationships. Stat Med 2007;26:3735–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glymour MM, Weuve J, Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Robins JM. When is baseline adjustment useful in analyses of change? An example with education and cognitive change. Am J Epidemiol 2005;162:267–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li N, Spiegelman D, Drain P, Mwiru RS, Mugusi F, Chalamilla G, Fawzi WW. Predictors of weight loss after HAART initiation among HIV-infected adults in Tanzania. AIDS 2012;26:577–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weiser SD, Young SL, Cohen CR, Kushel MB, Tsai AC, Tien PC, Hatcher AM, Frongillo EA, Bangsberg DR. Conceptual framework for understanding the bidirectional links between food insecurity and HIV/AIDS. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:1729S–39S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mangili A, Murman DH, Zampini AM, Wanke CA. Nutrition and HIV infection: review of weight loss and wasting in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy from the nutrition for healthy living cohort. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:836–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miettinen O. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, 1985 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silberman H. Consequences of malnutrition. : Silberman H. ed. Norwalk, CT: Appleton & Lang, 1989:1–18 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tomkins A, Watson F. Malnutrition and infection: a review. ACC/SCN State-of-the-Art Series: Nutrition Policy discussion paper #5. Geneva, Switzerland: ACC/SCN, 1989.

- 25.Beisel WR. Nutrition and immune function: overview. J Nutr 1996;126:2611S–5S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ambrus JL, Sr, Ambrus JL. Nutrition and infectious diseases in developing countries and problems of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2004;229:464–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scrimshaw NS, SanGiovanni JP. Synergism of nutrition, infection, and immunity: An overview. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;66:464S–77S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Lettow M, Harries AD, Kumwenda JJ, Zijlstra EE, Clark TD, Taha TE, Semba RD. Micronutrient malnutrition and wasting in adults with pulmonary tuberculosis with and without HIV co-infection in Malawi. BMC Infect Dis 2004;4:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caulfield LE, Richard SA, Rivera JA, Musgrove P, Black RE. Stunting, wasting, and micronutrient deficiency disorders. 2nd ed. In: Disease control priorities in developing countries. Washington, DC: The World Bank and Oxford University Press, 2006:551–67.

- 30.Yakoob MY, Theodoratou E, Jabeen A, Imdad A, Eisele TP, Ferguson J, Jhass A, Rudan I, Campbell H, Black RE, et al. Preventive zinc supplementation in developing countries: impact on mortality and morbidity due to diarrhea, pneumonia and malaria. BMC Public Health 2011;11(suppl 3):S23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cantrell RA, Sinkala M, Megazinni K, Lawson-Marriott S, Washington S, Chi BH, Tambatamba-Chapula B, Levy J, Stringer EM, Mulenga L, et al. A pilot study of food supplementation to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy among food-insecure adults in Lusaka, Zambia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;49:190–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lamb MR, El-Sadr WM, Geng E, Nash D. Association of adherence support and outreach services with total attrition, loss to follow-up, and death among ART patients in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e38443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Weiser SD, Bangsberg DR, Kegeles S, Ragland K, Kushel MB, Frongillo EA. Food insecurity among homeless and marginally housed individuals living with HIV/AIDS in San Francisco. AIDS Behav 2009;13:841–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weiser SD, Tsai AC, Gupta R, Frongillo EA, Kawuma A, Senkungu J, Hunt PW, Emenyonu NI, Mattson JE, Martin JN, et al. Food insecurity is associated with morbidity and patterns of healthcare utilization among HIV-infected individuals in a resource-poor setting. AIDS 2012;26:67–75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kalichman SC, Pellowski J, Kalichman MO, Cherry C, Detorio M, Caliendo AM, Schinazi RF. Food insufficiency and medication adherence among people living with HIV/AIDS in urban and peri-urban settings. Prev Sci 2011;12:324–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koethe JR, Limbada MI, Giganti MJ, Nyirenda CK, Mulenga L, Wester CW, Chi BH, Stringer JS. Early immunologic response and subsequent survival among malnourished adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in Urban Zambia. AIDS 2010;24:2117–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Toure S, Kouadio B, Seyler C, Traore M, Dakoury-Dogbo N, Duvignac J, Diakite N, Karcher S, Grundmann C, Marlink R, et al. Rapid scaling-upof antiretroviral therapy in 10,000 adults in Cote d'Ivoire: 2-year outcomes and determinants. AIDS 2008;22:873–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koethe JR, Jenkins CA, Shepherd BE, Stinnette SE, Sterling TR. An optimal body mass index range associated with improved immune reconstitution among HIV-infected adults initiating antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53:952–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mamlin J, Kimaiyo S, Lewis S, Tadayo H, Jerop FK, Gichunge C, Petersen T, Yih Y, Braitstein P, Einterz R. Integrating nutrition support for food-insecure patients and their dependents into an HIV care and treatment program in Western Kenya. Am J Public Health 2009;99:215–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization Essential prevention and care interventions for adults and adolescents living with HIV in resource-limited settings. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Swaminathan S, Padmapriyadarsini C, Yoojin L, Sukumar B, Iliayas S, Karthipriya J, Sakthivel R, Gomathy P, Thomas BE, Mathew M, et al. Nutritional supplementation in HIV-infected individuals in South India: a prospective interventional study. Clin Infect Dis 2010;51:51–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reddi A, Powers MA, Thyssen A. HIV/AIDS and food insecurity: deadly syndemic or an opportunity for healthcare synergism in resource-limited settings of sub-Saharan Africa? AIDS 2012;26:115–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mekonnen Y, Dukers NH, Sanders E, Dorigo W, Wolday D, Schaap A, Geskus RB, Coutinho RA, Fontanet A. Simple markers for initiating antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected Ethiopians. AIDS 2003;17:815–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kotler DP, Rosenbaum K, Wang J, Pierson RN. Studies of body composition and fat distribution in HIV-infected and control subjects. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol 1999;20:228–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]