Abstract

Papillary fibroelastoma of the aortic valve is an uncommon benign tumor of the heart that can present with embolic events. We report a case of 54-year-old lady with exertional chest pain and prior history of ST segment elevation myocardial infarction who was subsequently found to have a fibroelastoma of the aortic valve. The absence of angiographically significant coronary artery disease and resolution of anginal symptoms post-surgery in our patient points to the possibility of fibroelastoma causing these anginal symptoms. Although uncommon, fibroelastoma are being recognized more frequently with the help of transesophageal echocardiography. Hence, in the absence of significant coronary artery disease, we emphasize the importance of consideration of papillary fibroelastoma of the aortic valve as a cause of angina. We also discuss the key aspects of the fibroelastoma including presentation, diagnostic modalities and treatment options.

Keywords: Papillary fibroelastoma, Angina, Aortic valve, Surgical resection, Embolic event

Core tip: Papillary fibroelastoma of the aortic valve is an uncommon benign tumor of the heart which can present with embolic events. In this report we present a 54-year-old female with prior history of ST segment elevation myocardial infarction who presented with exertional chest pain. She was subsequently found to have a papillary fibroelastoma of the aortic valve.

INTRODUCTION

Papillary fibroelastoma (PFE) is the third most common benign primary tumor of the heart that usually involves the cardiac valves. Clinical presentation of PFE varies widely, ranging from asymptomatic to severe ischemic or embolic events. PFE are being recognized more frequently with the help of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and should be differentiated from thrombus, vegetation, myxoma and Lambl’s excrescence. Symptomatic cardiac PFE should be surgically removed whereas asymptomatic lesions that are left-sided, mobile or larger than 1 cm should be considered for surgical excision. Recurrence after surgery has not been reported, and the long-term postoperative prognosis is excellent.

Here in this report, we present a case of 54-year-old female patient with prior history of ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) who presented with exertional chest pain. She was subsequently found to have a PFE of the aortic valve.

CASE REPORT

A 54-year-old female with history of obesity, hyperlipidemia and hypertension and prior STEMI presented with exertional chest tightness of 3 mo duration. Two years prior to this presentation, she had suffered an anterior STEMI. Emergent cardiac catheterization at that time had revealed a total occlusion of distal left anterior descending (LAD) artery with no angiographic evidence of coronary atherosclerosis elsewhere. She was treated with primary balloon angioplasty and stenting was not done secondary to a small vessel caliber. She had a TTE done afterwards, which showed apical akinesis and an ejection fraction of 45%. Rest of the TTE was within normal limits including valvular anatomy and function. She was discharged on aspirin, simvastatin and metoprolol. She remained symptom free till 3 mo before presentation. She had started noticing chest tightness after joining exercise classes to lose weight. The tightness was similar in quality to her STEMI pain but much less intense in severity and resolved in 5 min after rest. Rest of her review of systems was negative.

Physical examination was unremarkable, except for obesity. Electrocardiogram did not reveal any pathological Q waves or evidence of ischemia or infarction. A treadmill stress test with myocardial perfusion imaging revealed a predominantly fixed defect at the lateral cardiac apex suggestive of the prior infarct; no ischemia was noted. A TTE done to assess left ventricular function revealed normal left ventricular function with mild hypokinesis in the prior infarct territory. However, TTE incidentally revealed a well-circumscribed 1 cm mass on the aortic side of the right coronary cusp of the aortic valve, concerning for a PFE. She had no risk factors, symptoms or signs suggestive of infective endocarditis or valvular thrombus. Further review of systems at this point failed to reveal any systemic embolic phenomenon. TEE was done to further characterize the mass. TEE revealed a well-circumscribed echo dense mass adherent to the edge of the right coronary cusp with a thin stalk and with minimal independent motion (Figure 1). The mass measured 0.9 cm in diameter. The aortic leaflets appeared normal in thickness and flexibility.

Figure 1.

Mid esophageal aortic valve long axis view showing the papillary fibroelastoma attached to the aortic side of the right coronary cusp.

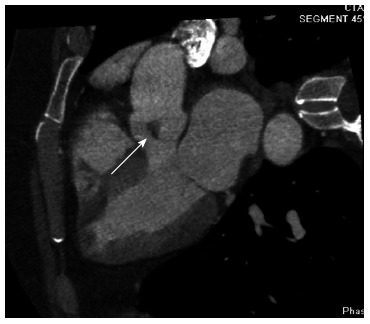

With her history of prior STEMI in the LAD territory without coronary atherosclerosis elsewhere, a concern was raised for a possible “embolic MI” in the past. As PFEs are known to cause embolic complications, especially when they are large, stalked and mobile, a recommendation was made for surgical resection of the mass. She underwent cardiac computed tomography (CT) angiography in preparation for the valve surgery to rule out obstructive coronary artery disease (instead of cardiac catheterization to prevent mass embolization with catheter manipulation). CT angiography failed to reveal any coronary atherosclerosis and reconfirmed the presence of PFE (Figure 2). Surgical removal of the mass without valve replacement was performed without complications.

Figure 2.

Cardiac computed tomography five chamber view showing the papillary fibroelastoma attached to the right coronary cusp.

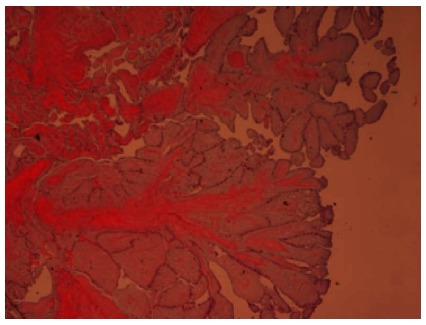

The mass measured 1.0 cm × 0.8 cm × 0.5 cm and histopathological examination was consistent with benign papillary fibroelastoma (Figure 3). Patient remained free of symptoms after surgery.

Figure 3.

Histopathology. Hematoxylin and eosin stain showing papillary fibroelastoma with narrow, elongated and branching papillary fronds with central avascular collagen and elastic tissue (Low power view, 40 × magnification).

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of primary cardiac tumor ranges from 0.002%-0.28%[1]. Papillary fibroelastoma originates most commonly from the valvular endocardium (85%). Aortic valve is most often involved (29%), followed by mitral valve (25%), tricuspid valve (17%) and pulmonary valves (13%)[2]. Although highest prevalence is seen in the eighth decade of life, it has been described in patients aged 6 d to 92 years[2]. Embolization is the most common clinical presentation, which may include but are not limited to stroke, myocardial infarction, mesenteric ischemia, renal infarction, limb ischemia, pulmonary embolism, and pulmonary hypertension. Patients can also present with heart failure, ventricular fibrillation and sudden death. Fibroelastoma arising from the aortic valve have been implicated in occurrence of sudden death by causing transient or complete obstruction of the ostium of coronary arteries[1,2]. Atrioventricular valve fibroelastoma can obstruct ventricular filling resulting in recurrent pulmonary edema and right-heart failure, mimicking a clinical picture of mitral or tricuspid valve stenosis. Conduction system disturbances and complete atrioventricular block have also been reported[3]. Rarely, aortic valve PFE is also noted to cause angina secondary to transient obstruction of the coronary ostium[2].

The common differential diagnosis of PFE includes other cardiac tumors (myxoma), vegetation, thrombus and Lambl’s excrescence. These can be differentiated by clinical presentation, location and character of the mass on TTE, TEE, cardiac CT or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The diagnosis is usually made by TTE or TEE, although, TEE is more sensitive. Echocardiography shows a small, pedunculated or sessile valvular or endocardial mobile mass, with a pedicle attached to the valve or endocardial surface and a frond-like appearance with or without multifocal involvement into the cardiac chambers. Echocardiographically, papillary fibroelastomas appear speckled with echolucencies near the edges. They have stippled edges. Mobility of the tumor is an independent predictor of nonfatal embolization and death. Computed tomography is inferior to transesophageal echocardiography in demonstrating the small moving structures. However, MRI is more valuable than computed tomography by imaging in multiple planes and better soft-tissue characterization of tumor. Gadolinium may enhance the differences between tumor and surrounding normal cardiac structures. 3-D echocardiography has also been used for better delineation of cardiac tumors[4]. Cardiac catheterization prior to resection of a PFE is subject to debate because of the friable nature of the lesion and because of the potential risk of embolization. On coronary angiography, the total occlusions or narrowing of distal coronary branches due to tumor emboli can be seen[5].

Grossly, PFE looks like a sea anemone because of its multiple papillary fronds. Papillary fibroelastoma are small avascular tumors with a single layer of endocardial cells covering the papillary surface[5]. Matrix consists of elastic fibers, proteoglycans, and spindle cells that resemble smooth muscle cells or fibroblasts. The layer of elastic fibers is a hallmark of this tumor. The connective tissue of fibroelastoma contains longitudinally oriented collagen with irregular elastic fibers[6].

Asymptomatic patients can be treated surgically if the tumor is mobile. Patients with asymptomatic non-mobile papillary fibroelastoma can be followed-up closely with periodic clinical evaluation and echocardiography, and they receive surgical intervention when the tumor becomes mobile or symptomatic[7]. Shave excision is successful in 83% of patients without the need for valvular repair or replacement[8]. TEE can also guide the surgical resection and assess the adequacy of valve repair both perioperatively and postoperatively. The surgical resection is curative, safe and well tolerated. Mechanical damage to the heart valve or adhesion of tumor to valve may necessitate valve repair or replacement[9]. Sastre-Garriga et al[10] recommend long-term anticoagulation for symptomatic patients who are not surgical candidates.

In our case, occurrence of STEMI in distal LAD with normal coronary artery elsewhere does raise a question of possible embolic myocardial infarction. The mass could have been small, or partially embolized and hence missed by the TTE at that time. PFE grows at a rate of 2-70 mm over a 1-year period[7]. The absence of angiographically significant coronary artery disease and resolution of anginal symptoms post-surgery in our patient points to the possibility of PFE causing these anginal symptoms. It is possible that the proximity of the stalked PFE on the right coronary cusp to the ostium of the right coronary artery (RCA) caused dynamic obstruction to the flow in the RCA, especially during exercise (demand ischemia); although, we could not explain the lack of ischemic findings during exercise myocardial perfusion imaging. Also, coronary vasospasm and multiple embolic events seem to be unlikely in our case as the symptoms occurred only during exertion, there was lack of electrocardiographic abnormalities and new perfusion defects during the exercise myocardial perfusion imaging. In summary, we presented a case of papillary fibroelastoma of the aortic valve causing anginal symptoms and possibly a myocardial infarction in the past.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Supriya Kuruvilla, MD of the Department of Pathology at the Reading Health System for her valuable contribution.

Footnotes

P- Reviewers Jha NK, Kounis NG S- Editor Huang XZ L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN

References

- 1.Jha NK, Khouri M, Murphy DM, Salustri A, Khan JA, Saleh MA, Von Canal F, Augustin N. Papillary fibroelastoma of the aortic valve--a case report and literature review. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;5:84. doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-5-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bruno VD, Mariscalco G, De Vita S, Piffaretti G, Nassiacos D, Sala A. Aortic valve papillary fibroelastoma: a rare cause of angina. Tex Heart Inst J. 2011;38:456–457. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas MR, Jayakrishnan AG, Desai J, Monaghan MJ, Jewitt DE. Transesophageal echocardiography in the detection and surgical management of a papillary fibroelastoma of the mitral valve causing partial mitral valve obstruction. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1993;6:83–86. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(14)80260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Araoz PA, Eklund HE, Welch TJ, Breen JF. CT and MR imaging of primary cardiac malignancies. Radiographics. 1999;19:1421–1434. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.19.6.g99no031421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumbala D, Sharp T, Kamalesh M. "Perilous pearl"--papillary fibroelastoma of aortic valve: a case report and literature review. Angiology. 2008;59:625–628. doi: 10.1177/0003319707305986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fishbein MC, Ferrans VJ, Roberts WC. Endocardial papillary elastofibromas. Histologic, histochemical, and electron microscopical findings. Arch Pathol. 1975;99:335–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gowda RM, Khan IA, Nair CK, Mehta NJ, Vasavada BC, Sacchi TJ. Cardiac papillary fibroelastoma: a comprehensive analysis of 725 cases. Am Heart J. 2003;146:404–410. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ngaage DL, Mullany CJ, Daly RC, Dearani JA, Edwards WD, Tazelaar HD, McGregor CG, Orszulak TA, Puga FJ, Schaff HV, et al. Surgical treatment of cardiac papillary fibroelastoma: a single center experience with eighty-eight patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:1712–1718. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loire R, Pinède L, Donsbeck AV, Nighoghossian N, Perinetti M. [Papillary fibroelastoma of the heart (giant Lambl excrescence). Clinical-anatomical study on 10 surgically treated patients] Presse Med. 1998;27:753–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sastre-Garriga J, Molina C, Montaner J, Mauleón A, Pujadas F, Codina A, Alvarez-Sabín J. Mitral papillary fibroelastoma as a cause of cardiogenic embolic stroke: report of two cases and review of the literature. Eur J Neurol. 2000;7:449–453. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2000.00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]