Abstract

This study investigated the role of angiotensin II receptor blocker in atrial remodeling in rats with atrial fibrillation (AF) induced by a myocardial infarction (MI). MIs were induced by a ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Two days after, the rats in the losartan group were given losartan (10 mg/kg/day for 10 weeks). Ten weeks later, echocardiography and AF induction studies were conducted. Ejection fraction was significantly lower in the MI rats. Fibrosis analysis revealed much increased left atrial fibrosis in the MI group than sham (2.22 ± 0.66% vs 0.25 ± 0.08%, P = 0.001) and suppression in the losartan group (0.90 ± 0.27%, P 0.001) compared with the MI group. AF inducibility was higher in the MI group than sham (39.4 ± 43.0% vs 2.0 ± 6.3%, P = 0.005) and significantly lower in losartan group (12.0 ± 31.6%, P = 0.029) compared with the MI. The left atrial endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS) and sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase levels were lower in the MI group and higher in the losartan group significantly. The atrial inducible NOS and sodium-calcium exchanger levels were higher in the MI and lower in the losartan group significantly. Losartan disrupts collagen fiber formation and prevents the alteration of the tissue eNOS and iNOS levels, which prevent subsequent AF induction.

Keywords: Atrial Fibrillation, Heart Failure, Fibrosis, Angiotensin Receptor Blocker

INTRODUCTION

The increasing incidence of heart failure (HF) and the aging of the population have led to an increased incidence of atrial fibrillation (AF). AF is a commonly occurring arrhythmia, present in people older than age 65 yr. The Framingham Heart Study reported that the lifetime risk for the development of AF is 1 in 4 for men and women aged 40 yr and older (1). AF is a major cause of morbidity and mortality, and increases the risk for death (2, 3), congestive heart failure (CHF) (2), and embolic phenomena including strokes (2, 4). Among several causes of AF, CHF is one of the most important causes. CHF is an increasingly frequent cardiovascular disorder that affects 15-20 million people worldwide. In the Framingham experience, CHF increase the risk of AF 4.5-fold in men and 5.9-fold in women (5). Both AF and CHF are linked to an increased activation of the renin-angiotensin system, which has been related to myocardial fibrosis in hypertensive heart disease (6), CHF, myocardial infarction (MI) (7), and cardiomyopathy (8).

Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) have been reported to decrease the formation of ventricular fibrosis in rat models (9) and to decrease the incidence of AF in humans (10). In a dog model of ventricular tachypacing (VTP) induced HF, treatment with inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme decreased the duration of AF via interfering with fibrosis formation induced by the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) (11). An increased angiotensin II action has been implicated in endothelial dysfunction characterized by a alternation of PKG signaling pathway and decreased nitric oxide (NO) availability (12). Increased expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) was identified in the myocardial endothelium of atrium in patients treated with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (13).

In the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) study, treatment with losartan resulted in a decreased incidence of atrial fibrillation and stroke (10). However, the exact mechanism for the anti-arrhythmic effects of ARBs is unknown, especially as related to effects on the NO system. Recently, several studies have demonstrated a relationship between AF and nitric oxide synthase (NOS). For example, Shiroshita-Takeshita et al. (14) showed a relationship between eNOS and AF in a dog atrial tachycardia model. Cai et al. (15) found that endocardial NOS expression and NO production were decreased in a pig model of AF. The angiotensin II levels are increased in CHF and angiotensin II is an important regulator of CHF induced arrhythmogenesis (16). Therefore, there could be a relationship between the angiotensin II modulating NO system and the arrhythmogenesis in CHF. The aim of this study was to evaluate these relationships by examining ARB responses.

Atrial fibrosis is a major contributing factor to AF according to the findings of large animal and human studies (17, 18). However, the relationship between the fibrosis and AF has rarely been investigated in small animal models and the effects of several calcium regulatory proteins are still disputed. Recently, the animal models for in vivo study of acute AF have been limitedly available in large animals (e.g., dogs, pigs or sheep), which cannot be easily studied in most laboratories. However, the induction of AF was recently demonstrated by atrial burst pacing in animals as small as mice (19). Therefore, this study also evaluated the correlation between fibrosis and AF, and between angiotensin II and NOS, in a rat atrial fibrosis model created by post myocardial infarction induced heart failure. The antiarrhythmic effects of ARBs and the relationship between angiotensin II modulation of NOS and several arrhythomogenic pathways were also explored.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and preparation

All animal-handling procedures were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of the Kosin University School of Medicine, which followed the guidelines of the Korean Council on Animal Care. Male Sprague-Dawley (SD, Daehan Biolink Inc. Eumseong, Korea) rats (n = 30), aged 7 to 8 weeks and weighing 250 to 300 g, were fed a normal sodium diet, and offered tap water. MI was induced by a ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery. Two days after induction of the MI, the rats were randomized into 2 groups: an untreated MI group (n = 10) and a MI+Losartan group (n = 10) that received losartan at 10 mg/kg/day for 10 weeks. The drug was added to the drinking water and water consumption and body weight were carefully monitored for the entire 10-week treatment. Sham operated rats served as a control (n = 10).

Creating the MI rat models

MIs were induced in the SD rats after ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery under an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (50 mg/kg) with xylazine (10 mg/kg). The rats were connected to a respirator (Harvard, Rodent Ventilator, model 683, with a frequency of 60 ventilations per minute, and a volume of 1 mL/100g). The chest was opened by a mid-sternotomy, and the left anterior descending artery was ligated approximately 2 to 3 mm from its origin with a 5.0 polypropylene suture (Ethicon, Diegem, Belgium). The control rats were submitted to a sham operation that used a similar procedure but without coronary ligation. The perioperative mortality was around 40% in the rats submitted to the coronary artery ligation.

Echocardiogram

At the end of the study, the rats were lightly anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (25 mg/kg) with xylazine (5 mg/kg). Transthoracic echocardiography was performed using a 12-MHz phased-array probe (Acuson Sequoia C512; Mountain View, CA, USA). The wall thickness and LV diameters during diastole and systole were measured from the M-mode recordings according to the leading-edge method. Two dimensional short-axis images at the mid-papillary muscle level were obtained for the measurement of the LV end-diastolic dimension (LVEDD), LV end-systolic dimension (LVESD), fractional shortening (FS), and wall thickness. The ejection fraction (EF) was calculated as follows: EF = (D2-S2)/D2 × 100, where S was the systolic and D the diastolic dimension (expressed in cm). The left atrial and aortic diameters were measured from the M-mode recordings in a modified parasternal long axis view.

Electrophysiological study

On the open chest study days, the rats were anesthetized with ketamine (90 mg/kg) and xylazine (13 mg/kg) and ventilated mechanically. The AF induction was performed in an open-chest state, with a bipolar lead attached to the right atrial appendage. Bipolar hook electrode was made by 2 Bipac unipolar 26-gauge needle electrodes 37 mm TP-EL450, (Biopac, Inc., Santa Barbara, CA, USA). AF was induced by right atrial burst pacing (using 4 times current of the pacing threshold for 30 seconds at 600 bpm). AF was induced ten times if the AF duration was ≤ 20 min, and five times if the AF lasted between 20 and 30 min. AF that lasted more than 30 min was considered to be persistent. Persistent AF was counted as 30 min duration. The mean duration of AF in each rat was determined on the basis of 10 inductions.

Quantification of fibrosis

After the completion of the electrophysiological study, the heart was rapidly removed and weighed and the heart to body weight ratio was calculated. The hearts were immersed in a 10% buffered formalin solution and then embedded in paraffin. Masson trichrome staining was used to characterize the collagen fibers. Fibrosis of the left atria was quantified with Image-Pro Plus version 5.1 acquisition software (Media Cybernetics, Georgia, USA).

Western blotting

About 25 mg of rat left atrial tissue was homogenized in 1 mL of a modified tonic sucrose solution (0.3 M/L sucrose, 10 mM/L imidazole, 10 mM/L sodium metabisulfite, 1 mM/L DTT, 0.3 mM/L PMSF) and centrifuged at 1,300 × g at 4℃ for 15 min. The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method. Aliquots containing 50 µg of protein for the iNOS and sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX) or 25 µg of protein for the eNOS and sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA) were loaded onto a SDS-polyacrylamide gel and separated by electrophoresis (11% acrylamide separating gel for 90 min). The separated proteins were electrophoretically transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) using a Trans-Blot semi-dry transfer system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) at 25V for 90 min in a buffer containing 25 mM/L Tris base, 192 mM/L glycine, and 20% methanol. The membranes were incubated at 4℃ overnight with mouse-anti rat-eNOS (BD Transduction Laboratories, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), iNOS (BD Transduction Laboratories), or NCX (Affinity BioReagents, Golden, CO, USA) monoclonal antibodies and with rabbit-anti-rat-SERCA (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) polyclonal antibodies at a 1:1,000 dilution in a TBST (0.2 M/L Tris, 1.37 M/L NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20; adjusted pH 7.6) containing 5% skim milk. After the incubation with a secondary antibody at a 1:1,500 dilution in a TBST containing 5% skim milk, the blot was developed using a SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate (Pierce) and exposed to X-ray film. The western blots were then analyzed by densitometry.

Immunohistochemistry for eNOS and iNOS

Immunohistochemistry for eNOS or iNOS was performed using a horseradish peroxidase-streptavidin-biotin method (UltraVision LP Detection System; Lab Vision Corporation, Suffolk, UK). Briefly, formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue was prepared using conventional histological methods. Serial sections (6 µm) were cut from each paraffin block. Samples were immersed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 30 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 15 min, blocked with normal goat serum for 15 min, and incubated with the primary antibodies: anti rat-polyclonal, diluted 1:50 with PBS, eNOS (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) for eNOS and rabbit-anti rat- polyclonal, diluted 1:50 with PBS, iNOS (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) for iNOS in a humidified chamber for 60 min. After treatment with primary antibody, samples were incubated with biotinylated secondary antibody for 30 min, followed by streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate for 15 min. Peroxidase was visualized by addition of 3-amino-9-ethyl carbazole (ACE) and hydrogen peroxide.

Drugs

Losartan was generous gift of Merck Pharmaceuticals (Whitehouse Station, NJ, USA).

Statistical analysis

Each parameter studied was statistically analyzed by an analysis of variance (ANOVA). If the results of ANOVA were significant, group-to-group comparisons were performed using the Mann-Whitney test. P values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All results were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). For the statistical analysis, SPSS software (version 12.0K) was used.

RESULTS

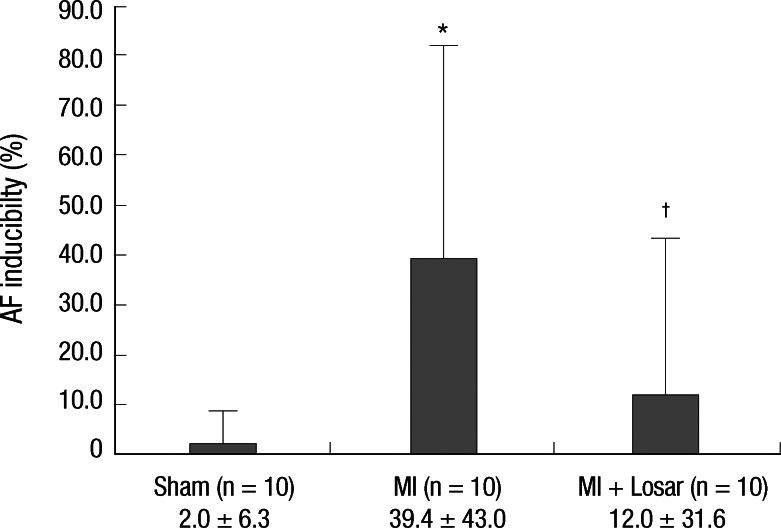

Echocardiographic indices

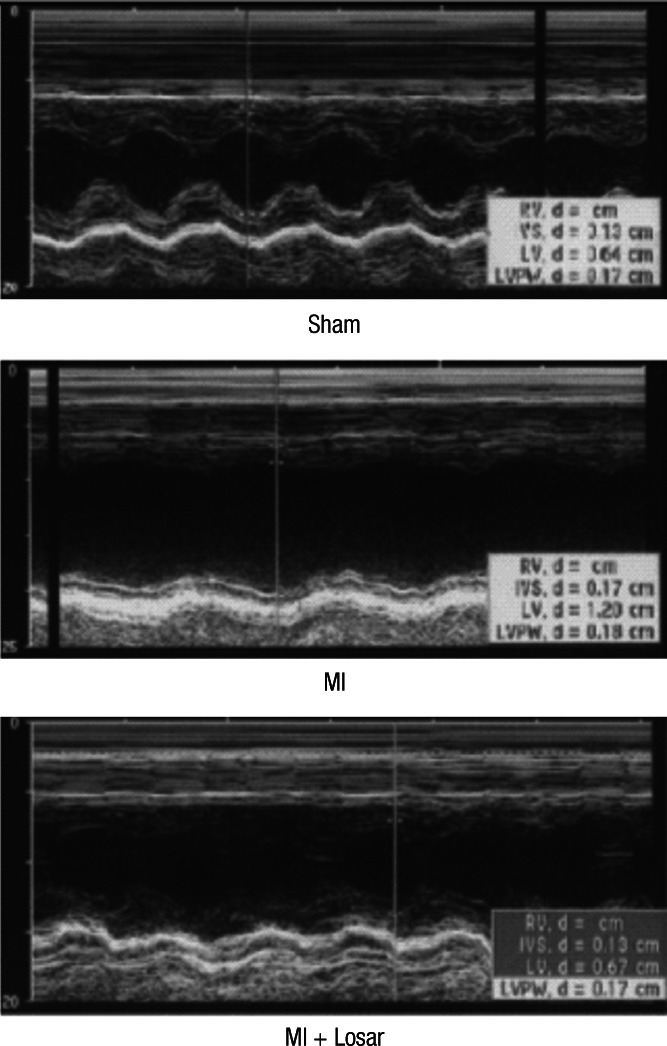

The changes in the echocardiographic parameters in each group are presented in Fig. 1 and Table 1. The left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was significantly lower in MI group than sham (sham, 91 ± 4%; MI, 37 ± 12%; mean ± S.D; P < 0.01). The LVEF was slightly higher in MI + losartan group (47 ± 19%) than MI group, and this difference was not statistically significant.

Fig. 1.

Echocardiograms using M-mode exhibiting left ventricular anteroseptal wall akinesia and dilated ventricular dimensions in MI rats. These changes were moderately abolished in the losartan treated rat group. MI, myocardial infarction; MI + Losar, myocardial infarction with losartan treatment.

Table 1.

Echocardiographic parameters

*P < 0.001, versus sham, †P < 0.01, versus sham. MI, myocardial infarction; MI + Losar, myocardial infarction with losartan; EF, ejection fraction; FS, fractional shortening; LVEDD, left ventricular end diastolic dimension; LVESD, left ventricular end systolic dimension; LAD, left atrial dimension.

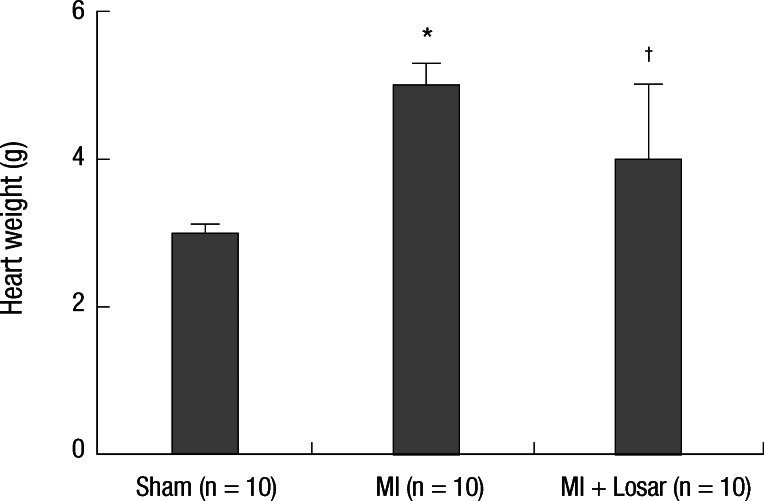

Changes in heart weight

Heart weight was significantly higher in the MI group than sham group (3.0 ± 0.1 gram in sham group [n = 10], 5.6 ± 0.3 gram in MI group [n = 10]; P < 0.001). It was significantly lower in losartan treatment group than MI group (4.0 ± 1.0 gram in MI + losartan group [n = 10]; P < 0.001, MI vs MI + losartan) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Changes in heart weight. *P < 0.001, sham vs MI; †P < 0.001, sham vs MI + Losartan, MI vs MI + Losartan. MI, myocardial infarction; MI + Losar, myocardial infarction with losartan treatment.

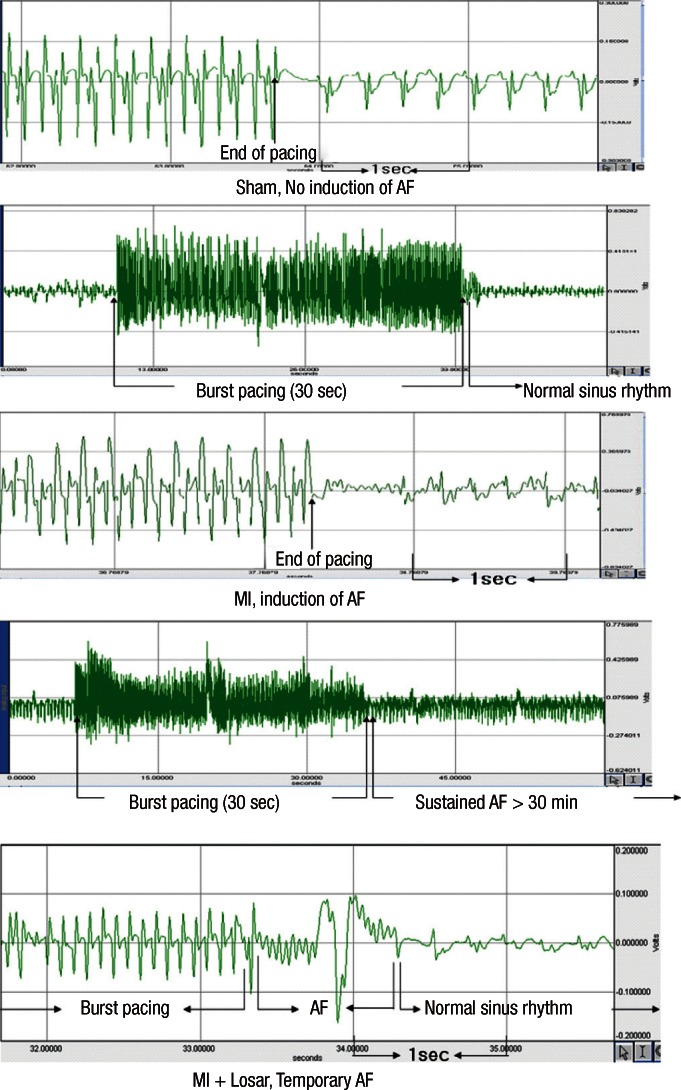

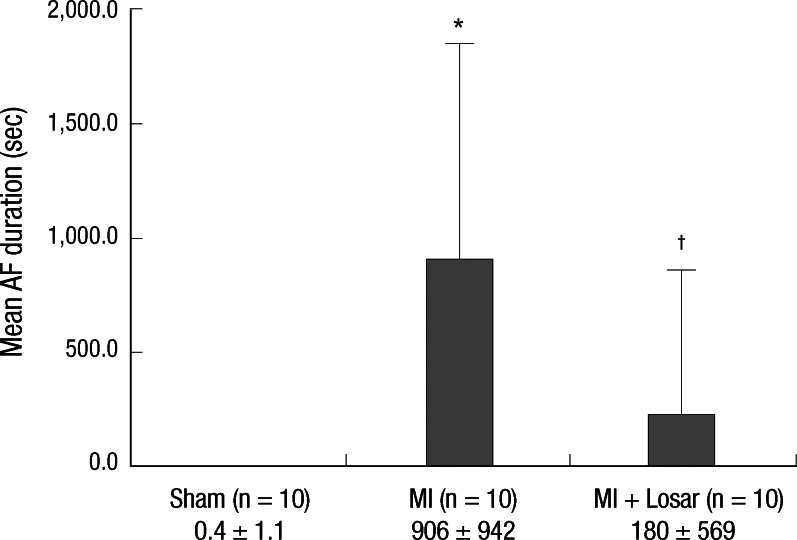

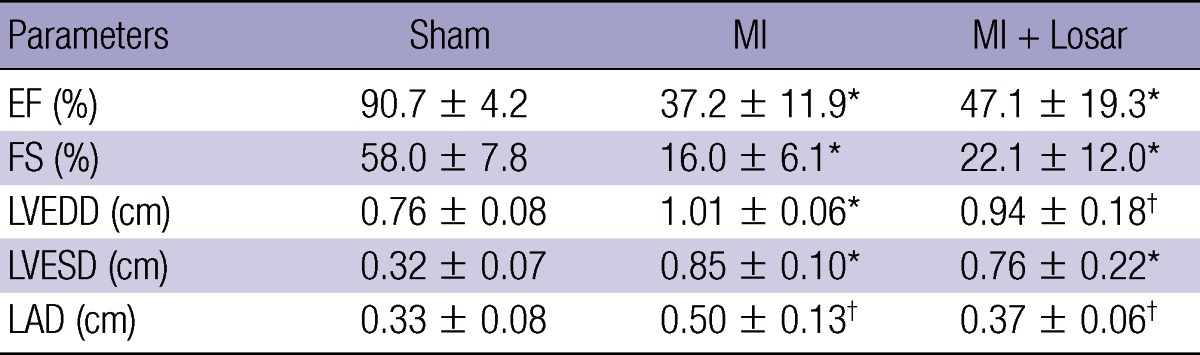

Atrial fibrillation induction study

Induction of AF was very difficult in the sham group. AF inducibility was higher in MI group than sham, and it was significantly lower in losartan treatment group (2.0 ± 6.3% in sham [n = 10]; 39.4 ± 43.0% in MI [n = 10]; 12.0 ± 31.6% in MI + losartan group [n = 10]; P = 0.005 sham versus MI, P = 0.029 MI vs MI + losartan). The AF duration was also significantly longer in the MI group than sham (906 ± 942 sec in MI [n = 10], 0.4 ± 1.1 sec in sham [n = 10]; P = 0.003). Losartan treatment significantly reduced the increase in AF duration (180 ± 569 sec [n = 10]; P = 0.015, MI vs MI + losartan) (Fig. 3-5).

Fig. 3.

The EKG shows the successful induction of atrial fibrillation following burst pacing in the MI group. On the contrary, there is no induction of atrial fibrillation in the sham group and short duration of AF in MI + Losartan group. AF, atrial fibrillation; MI, myocardial infarction; MI + Losar, myocardial infarction with losartan treatment.

Fig. 5.

Mean duration of atrial fibrillation (seconds) following burst pacing. *P = 0.003, sham vs MI; †P = 0.015, MI vs MI + losartan. MI, myocardial infarction; MI + Losar, myocardial infarction with losartan treatment.

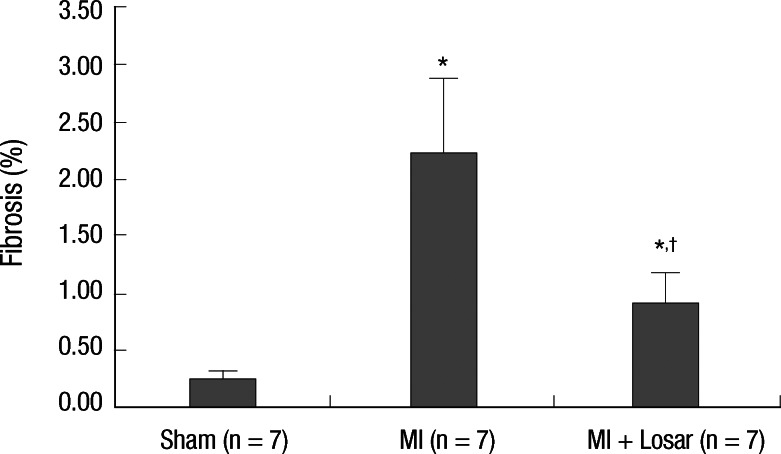

Effects of losartan on left atrial fibrosis in the MI rat model

The occurrence of MI significantly increased the interstitial fibrosis in the left atrium (sham, 0.25 ± 0.08% [n = 7]; MI, 2.22 ± 0.66% [n = 7]; P = 0.001). Treatment with losartan resulted in a significantly reduced amount of fibrosis in the left atrium compared to the MI group (MI + losartan, 0.90 ± 0.27% [n = 7]; P = 0.001, MI + losartan vs MI) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Effect of losartan on the fibrosis of the left atrium. *P = 0.001, sham vs MI and sham vs MI + losartan; †P = 0.001, MI vs MI + losartan. MI, myocardial infarction; MI + Losar, myocardial infarction with losartan treatment.

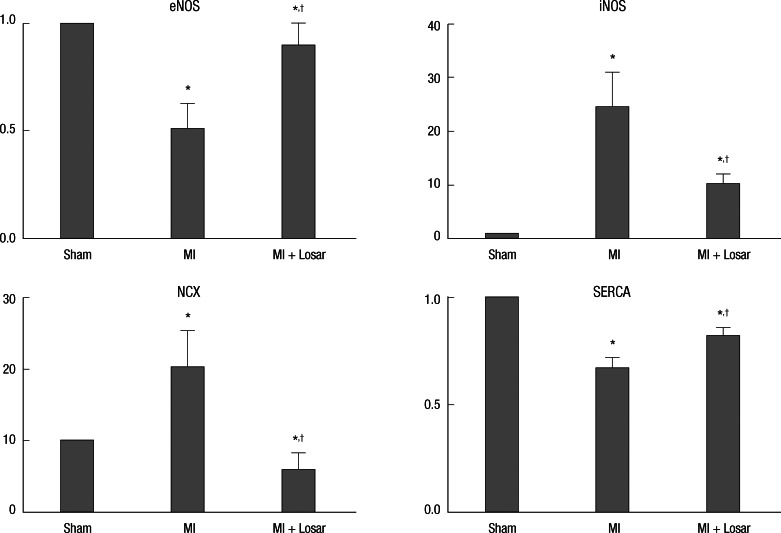

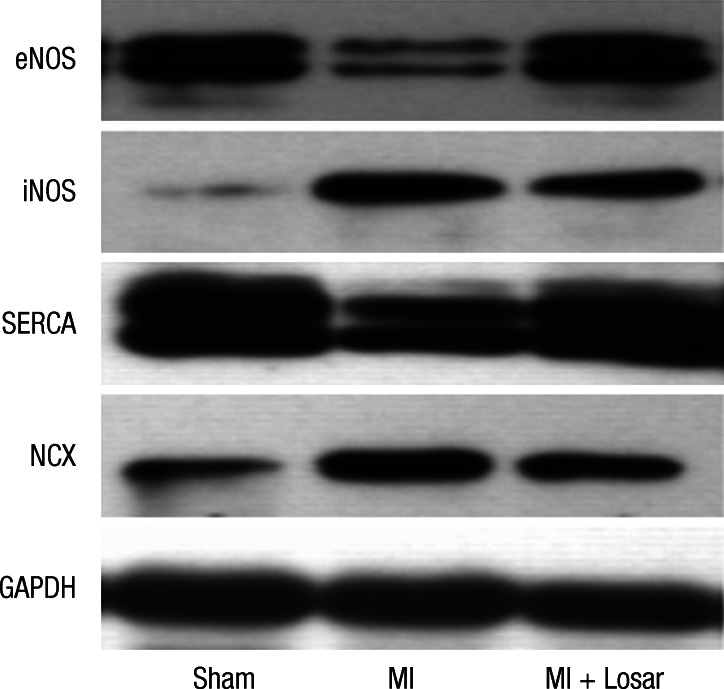

Expression of nitric oxide syntheses and calcium handling proteins

The left atrial tissue protein levels of eNOS were significantly lower in MI group (sham, 12.84 ± 2.78; MI, 6.56 ± 4.08; P < 0.01), and SERCA were significantly lower in the MI group than sham (sham, 28.59 ± 3.26; MI, 19.07 ± 3.53; P < 0.01). This reduction in eNOS and SERCA expression was diminished in the losartan treated group (eNOS, 11.65 ± 3.41; SERCA, 23.32 ± 2.72; P < 0.05). The left atrial tissue protein levels of iNOS were significantly higher in the MI group than sham (sham, 0.25 ± 0.30; MI, 6.09 ± 4.65; P <0.01) and NCX level were also higher in the MI group (sham, 0.78 ± 0.44; MI, 15.86 ± 12.91; P < 0.01). After treatment with losartan, the iNOS and NCX protein expression were decreased (iNOS, 2.51 ± 1.32; NCX, 4.73 ± 5.20; P < 0.05) (Fig. 7, 8).

Fig. 7.

Expression of nitric oxide synthase and calcium handling proteins. Data were normalized to the value of sham. *P < 0.01, sham vs MI and sham vs MI + Losartan; †P < 0.05, MI vs MI + Losartan. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; NCX, sodium calcium exchanger; SERCA, Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase; MI, myocardial infarction; MI+Losar, myocardial infarction with losartan treatment.

Fig. 8.

Alterations of the eNOS, iNOS, SERCA and NCX protein expression in the left atrium. eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; NCX, sodium calcium exchanger; SERCA, Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase; MI, myocardial infarction; MI + Losar, myocardial infarction with losartan treatment.

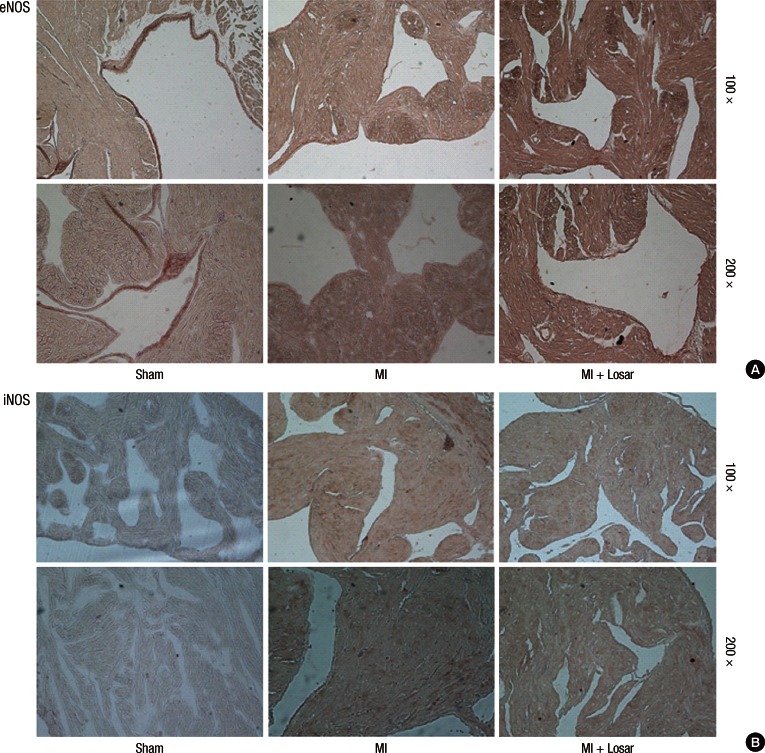

Immunohistochemistry results

The eNOS immunohistochemical staining showed that most eNOS activity was located in the endocardial area in the sham group. And the endocardial eNOS activity decreased in the MI group, but treatment with losartan restored endocardial eNOS activity. The iNOS immunohistochemical staining revealed little iNOS activity in the sham group. Myocardial iNOS activity was increased in the MI group, but this increase was suppressed by treatment with losartan (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Imuunohistochemical staining shows that eNOS expression are decreased in endocardium of MI group and increased in MI + losartan group (A). iNOS expression are increased in myocardium of MI group, and these expression are decreased in MI + losartan group (B). eNOS, endothelial nitric oxide synthase; iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; MI, myocardial infarction; MI + Losar, myocardial infarction with losartan treatment. Numbers standing on right column mean magnification.

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrated a simple and novel in vivo, open-chest, small animal AF model. The MI induced rat CHF model developed AF due to an increased amount of fibrosis, modulation of NOS, increased NCX activity and decreased SERCA expression in the left atrium (LA). Treatment with losartan reduced the CHF-induced arrhythmogenic left atrial remodeling that contributed to AF by reducing the amount of fibrosis and preventing changes in the NO system and in expression of calcium regulating proteins.

CHF produces a significant amount of atrial fibrosis, which is associated with localized conduction abnormalities that are believed to promote AF by stabilizing reentry (20, 21). Li et al. (11) demonstrated increased atrial fibrosis in a rapid pacing induced dog CHF model, and after treatment with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, fibrosis formation was prevented and the duration of AF was decreased. A chronic angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor blockade with losartan was associated with a reduction in both the myocardial collagen content and left ventricular chamber stiffness in a subgroup of patients with essential hypertension (22). The present study showed that an increased amount of LA fibrosis induced by CHF was associated with an increased duration of AF in the rat CHF model. In addition, the extent of LA fibrosis promoted by AF was diminished by losartan treatment. The decreased amount of fibrosis was correlated with a decreased duration of AF.

Activation of the renin-angiotensin system is an important mechanism of CHF induced atrial fibrillation. An increase in angiotensin II is related to superoxide formation and the alteration of the nitric oxide synthase system. Chung et al. (23) demonstrated an elevation of the C-reactive protein levels in patients with AF and showed that inflammation may be part of the mechanism underlying AF development. Cai et al. (15) reported the down-regulation of eNOS and increased expression of prothrombotic protein plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1) in the left atrial tissue following induction of AF in pigs. These results can explain the increased thrombogenicity of the left atrial tissue in AF. Shiroshita-Takeshita et al. (14) reported an increase in eNOS and iNOS expression in atrial tissues of dogs that had undergone atrial tachycardia remodeling. The elevation of the eNOS expression was decreased after treatment with prednisone. However, these changes in eNOS and iNOS were reported in atrial tissues remodeled by atrial tachycardia. The present study is the first to show a relationship between NOS expression and arrhythmogenesis during CHF. We showed a decrease in eNOS expression in left atrial tissue from rats with CHF. These results indicate that CHF occurring after myocardial infarction increased thrombogenicity and also increased the probability of atrial fibrillation.

Recent studies have shown that iNOS is either undetectable or detected at only low levels in healthy human hearts, but it is expressed at high levels in the myocardium of failing hearts (24). High concentrations of NO have been shown to induce cardiomyocyte apoptosis (25). Elevation of iNOS expression within the cardiomyocytes of failing hearts may contribute to the pathogenesis of progressive LV remodeling and heart failure (26). In transgenic mice, the cardiac-specific over-expression of iNOS leads to cardiac fibrosis, dilatation, and premature death (27). Sam et al. (28) demonstrated that six months after a myocardial infarction, the extent of the LV dysfunction and myocardial apoptosis was diminished in iNOS knockout mice, which supported a detrimental role for iNOS in this chronic HF model. Patten et al. (26) demonstrated that ventricular assist device therapy normalized iNOS expression and reduced cardiomyocyte apoptosis in failing human hearts.

CHF induces the activation of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha, which inhibits the expression of eNOS and stimulates the expression of iNOS (29, 30). Recent studies have demonstrated a relationship between elevated iNOS and arrhythmia. For example, Xia et al. (31) demonstrated up-regulation of inflammatory factors such as endothelin, NFκB, TNFα, and iNOS and their involvement in exaggerated cardiac arrhythmias in L-thyroxine-induced cardiomyopathy. The results of the present study indicated a significantly increased iNOS expression in CHF, which was significantly improved after the losartan treatment. The reduction in iNOS expression, along with the decreased amount of fibrosis, was associated with decreased arrhythmogenesis and especially with decreased AF development in the atrium.

CHF-induced contractile dysfunction and increased arrhythmogenesis are related to alterations in intracellular calcium concentrations. Intraluminal free calcium levels are increased in diastole and decreased in systole in a CHF state. These calcium homeostasis changes are related to changes in NCX, SERCA, and other calcium regulatory proteins in the sarcoplasmic reticulum. CHF increased the expression of NCX, an important carrier of post-repolarization transient inward currents that cause delayed after-depolarizations (DADs). DADs can induce triggered activity, and there is evidence for the role of DADs in atrial tachyarrhythmias in canine CHF models (18, 32). The present study showed significantly increased NCX expression and significantly decreased SERCA expression in the rat CHF model. These effects were significantly suppressed by losartan treatment. Those findings support the idea that the anti-arrhythmic effects of losartan are induced by prevention of alteration of calcium handling induced by CHF.

This is the first study to demonstrate changes in eNOS, iNOS, NCX, and SERCA in heart failure atrial tissue associated with atrial fibrillation in rats. This study found that an increased iNOS, NCX, and fibrosis in the atrial tissue in the MI group could cause the development of sustained AF even in these small animals. Losartan treatment clearly decreased the amount of fibrosis in the atrium and was associated with a decreased duration of AF and decreased expression of eNOS. This, in turn, was associated with a decreased thrombogenicity in the atrial tissue. These results can provide some scientific support for the stroke prevention effects seen in the LIFE study (10). Another important finding was that this study demonstrated that losartan treatment led to a decreased expression of NCX, which was an important component of the arrhythromogenicity.

The present study demonstrated a simple and novel in vivo, open-chest, small animal AF model that eliminates the need to use large animals such as dogs or pigs. We clearly demonstrated the induction of sustained AF, so this animal model can simplify AF studies because of the ease in handling these animals.

The limitation of this study is that we did not measure the direct angiotensin II level in the atrial tissue. However, the increase in the angiotensin II levels has already been demonstrated in previous studies (33). The NCX current was not measured in the heart failure atrial tissue, because of the technical difficulty in doing so in small animals. Cell condition after a single cell isolation was very poor and we were unable to obtain cells in good condition from the CHF atrial tissue, which prevented direct measurement of the NCX current. This study also did not measure the effective refractory period of the rat atrial tissue, nor were elevated NCX-induced DADs demonstrated in the CHF tissue.

In conclusion, angiotension II induce remodeling of left atrial tissues in heart failure, which cause arrhythmia like atrial fibrillation. The MI induced rat CHF model developed AF due to an increased amount of fibrosis, modulation of NOS, increased NCX activity and decreased SERCA expression in the left atrium. Losartan, an angiotensin receptor blocker, disrupts collagen fiber formation and prevents the alteration of the tissue eNOS and iNOS levels, which may prevent subsequent AF induction.

Fig. 4.

Results of atrial fibrillation inducibility study. *P = 0.005, sham vs MI; †P = 0.029, MI vs MI + losartan. MI, myocardial infarction; MI + Losar, myocardial infarction with losartan treatment.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones DM, Wang TJ, Leip EP, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, D'Agostino RB, Massaro JM, Beiser A, Wolf PA, et al. Lifetime risk for development of atrial fibrillation: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2004;110:1042–1046. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000140263.20897.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stewart S, Hart CL, Hole DJ, McMurray JJ. A population-based study of the long-term risks associated with atrial fibrillation: 20-year follow-up of the Renfrew/Paisley Study. Am J Med. 2002;113:359–364. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benjamin EJ, Wolf PA, D'Agostino RB, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB, Levy D. Impact of atrial fibrillation on the risk of death: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1998;98:946–952. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.10.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991;22:983–988. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.8.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vaziri SM, D'Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Wolf PA. Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort: the Framingham Heart Study. JAMA. 1994;271:840–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brilla CG, Pick R, Tan LB, Janicki JS, Weber KT. Remodeling of the rat right and left ventricles in experimental hypertension. Circ Res. 1990;67:1355–1364. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.6.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanatani A, Yoshiyama M, Kim S, Omura T, Toda I, Akioka K, Teragaki M, Takeuchi K, Iwao H, Takeda T. Inhibition by angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist of cardiac phenotypic modulation after myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:1905–1914. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(95)90013-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urata H, Boehm KD, Philip A, Kinoshita A, Gabrovsek J, Bumpus FM, Husain A. Cellular localization and regional distribution of an angiotensin II-forming chymase in the heart. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:1269–1281. doi: 10.1172/JCI116325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanabe A, Naruse M, Hara Y, Sato A, Tsuchiya K, Nishikawa T, Imaki T, Takano K. Aldosterone antagonist facilitates the cardioprotective effects of angiotensin receptor blockers in hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2004;22:1017–1023. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200405000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wachtell K, Lehto M, Gerdts E, Olsen MH, Hornestam B, Dahlöf B, Ibsen H, Julius S, Kjeldsen SE, Lindholm LH, et al. Angiotensin II receptor blockade reduces new-onset atrial fibrillation and subsequent stroke compared to atenolol: the Losartan Intervention for End Point Reduction in Hypertension (LIFE) Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:712–719. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li D, Shinagawa K, Pang L, Leung TK, Cardin S, Wang Z, Nattel S. Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on the development of the atrial fibrillation substrate in dogs with ventricular tachypacing-induced congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:2608–2614. doi: 10.1161/hc4601.099402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin Y, Liu JC, Zhang XJ, Li GW, Wang LN, Xi YH, Li HZ, Zhao YJ, Xu CQ. Downregulation of the ornithine decarboxylase/polyamine system inhibits angiotensin-induced hypertrophy of cardiomyocytes through the NO/cGMP-dependent protein kinase type-I pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2010;25:443–450. doi: 10.1159/000303049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morawietz H, Rohrbach S, Rueckschloss U, Schellenberger E, Hakim K, Zerkowski HR, Kojda G, Darmer D, Holtz J. Increased cardiac endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression in patients taking angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy. Eur J Clin Invest. 2006;36:705–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2006.01715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiroshita-Takeshita A, Brundel BJ, Lavoie J, Nattel S. Prednisone prevents atrial fibrillation promotion by atrial tachycardia remodeling in dogs. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69:865–875. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.11.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai H, Li Z, Goette A, Mera F, Honeycutt C, Feterik K, Wilcox JN, Dudley SC, Jr, Harrison DG, Langberg JJ. Downregulation of endocardial nitric ox ide synthase expression and nitric oxide production in atrial fibrillation: potential mechanisms for atrial thrombosis and stroke. Circulation. 2002;106:2854–2858. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000039327.11661.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nattel S, Burstein B, Dobrev D. Atrial remodeling and atrial fibrillation: mechanisms and implications. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2008;1:62–73. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.107.754564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anné W, Willems R, Roskams T, Sergeant P, Herijgers P, Holemans P, Ector H, Heidbüchel H. Matrix metalloproteinases and atrial remodeling in patients with mitral valve disease and atrial fibrillation. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:655–666. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cha TJ, Ehrlich JR, Zhang L, Shi YF, Tardif JC, Leung TK, Nattel S. Dissociation between ionic remodeling and ability to sustain atrial fibrillation during recovery from experimental congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2004;109:412–418. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109501.47603.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang C, Yasuno S, Kuwahara K, Zankov DP, Kobori A, Makiyama T, Horie M. Blockade of angiotensin II type 1 receptor improves the arrhythmia morbidity in mice with left ventricular hypertrophy. Circ J. 2006;70:335–341. doi: 10.1253/circj.70.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Derakhchan K, Li D, Courtemanche M, Smith B, Brouillette J, Pagé PL, Nattel S. Method for simultaneous epicardial and endocardial mapping of in vivo canine heart: application to atrial conduction properties and arrhythmia mechanisms. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:548–555. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li D, Fareh S, Leung TK, Nattel S. Promotion of atrial fibrillation by heart failure in dogs: atrial remodeling of a different sort. Circulation. 1999;100:87–95. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Díez J, Querejeta R, López B, González A, Larman M, Martínez Ubago JL. Losartan-dependent regression of myocardial fibrosis is associated with reduction of left ventricular chamber stiffness in hypertensive patients. Circulation. 2002;105:2512–2517. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000017264.66561.3d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung MK, Martin DO, Sprecher D, Wazni O, Kanderian A, Carnes CA, Bauer JA, Tchou PJ, Niebauer MJ, Natale A, et al. C-reactive protein elevation in patients with atrial arrhythmias: inflammatory mechanisms and persistence of atrial fibrillation. Circulation. 2001;104:2886–2891. doi: 10.1161/hc4901.101760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fukuchi M, Hussain SN, Giaid A. Heterogeneous expression and activity of endothelial and inducible nitric oxide synthases in end-stage human heart failure: their relation to lesion site and beta-adrenergic receptor therapy. Circulation. 1998;98:132–139. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim YM, Bombeck CA, Billiar TR. Nitric oxide as a bifunctional regulator of apoptosis. Circ Res. 1999;84:253–256. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.3.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patten RD, Denofrio D, El-Zaru M, Kakkar R, Saunders J, Celestin F, Warner K, Rastegar H, Khabbaz KR, Udelson JE, et al. Ventricular assist device therapy normalizes inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and reduces cardiomyocyte apoptosis in the failing human heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1419–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.05.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mungrue IN, Gros R, You X, Pirani A, Azad A, Csont T, Schulz R, Butany J, Stewart DJ, Husain M. Cardiomyocyte overexpression of iNOS in mice results in peroxynitrite generation, heart block, and sudden death. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:735–743. doi: 10.1172/JCI13265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sam F, Sawyer DB, Xie Z, Chang DL, Ngoy S, Brenner DA, Siwik DA, Singh K, Apstein CS, Colucci WS. Mice lacking inducible nitric oxide synthase have improved left ventricular contractile function and reduced apoptotic cell death late after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2001;89:351–356. doi: 10.1161/hh1601.094993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson HD, Rahmutula D, Gardner DG. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibits endothelial nitric-oxide synthase gene promoter activity in bovine aortic endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:963–969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309552200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paz Y, Frolkis I, Pevni D, Shapira I, Yuhas Y, Iaina A, Wollman Y, Chernichovski T, Nesher N, Locker C, et al. Effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha on endothelial and inducible nitric oxide synthase messenger ribonucleic acid expression and nitric oxide synthesis in ischemic and nonischemic isolated rat heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;42:1299–1305. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00992-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xia HJ, Dai DZ, Dai Y. Up-regulated inflammatory factors endothelin, NFkappaB, TNFalpha and iNOS involved in exaggerated cardiac arrhythmias in l-thyroxine-induced cardiomyopathy are suppressed by darusentan in rats. Life Sci. 2006;79:1812–1819. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pogwizd SM, Schlotthauer K, Li L, Yuan W, Bers DM. Arrhythmogenesis and contractile dysfunction in heart failure: roles of sodium-calcium exchange, inward rectifier potassium current, and residual beta-adrenergic responsiveness. Circ Res. 2001;88:1159–1167. doi: 10.1161/hh1101.091193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaprielian RR, Dupont E, Hafizi S, Poole-Wilson PA, Khaghani A, Yacoub MH, Severs NJ. Angiotensin II receptor type 1 mRNA is upregulated in atria of patients with end-stage heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1997;29:2299–2304. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1997.0458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]