Abstract

A 4-yr-old girl has exhibited severe snoring, restless sleep and increasing daytime sleepiness over the last 3 months. The physical examination showed that she was not obese but had kissing tonsils. Polysomnography demonstrated increased apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) of 5.2, and multiple sleep latency tests (MSLT) showed shortened mean sleep latency and one sleep-onset REM period (SOREMP). She was diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and underwent tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. After the surgery, her sleep became much calmer, but she was still sleepy. Another sleep test showed normal AHI of 0.2, the mean sleep latency of 8 min, and two SOREMPs. Diagnosis of OSA to be effectively treated by surgery and narcolepsy without cataplexy was confirmed. Since young children exhibiting both OSA and narcolepsy can fail to be diagnosed with the latter, it's desirable to conduct MSLT when they have severe daytime sleepiness or fail to get better even with good treatment.

Keywords: Narcolepsy Without Cataplexy, Obstructive Sleep Apnea, Children

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which is a common sleep disorder in young children, involves nocturnal symptoms, such as snoring and sleep apnea (1). In addition, it can be accompanied by such behavioral impairments as hyperactivity, inattention, and excessive daytime sleepiness, exerting serious effects on their quality of life. By comparison, narcolepsy, which is a rare sleep disorder in young children, can be accompanied by specific symptoms, such as cataplexy, sleep paralysis, hypnagogic hallucination, and fragmented sleep, and is primarily found in adolescence or early adulthood (2). While both narcolepsy and OSA can cause excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), the former is very likely to be neglected if one has both conditions. In particular, diagnosis and treatment can center on OSA alone due to the low prevalence of narcolepsy in children of preschool age.

While the Korean literature has no case report of narcolepsy with OSA in children, we report a case of both narcolepsy and OSA in a 4-yr-old girl.

CASE DESCRIPTION

On May 2, 2012, a 4-yr-old girl was found to have exhibited severe snoring, restless sleep, and increasing daytime sleepiness over the last 3 months. Her mother reported that she snored terribly all over the night and that several pauses in her breathing were observed at night. The patient had no difficulty falling asleep at night and she had relatively regular sleep schedule from 21:00 to 07:00, but she usually awoke from her sleep 4 to 5 times during nighttime. In the morning, she hardly felt refreshed after a sleep and looked very tired even after getting out of bed. The child tended to be good at preschool learning and activities and she rarely has taken a nap in the kindergarten since September, 2011. However, she fell asleep in the middle of a class or took a nap for more than two hours, and even after coming back home, she complained of sleepiness and got another sleep for two hours or so in the afternoon in the last several months.

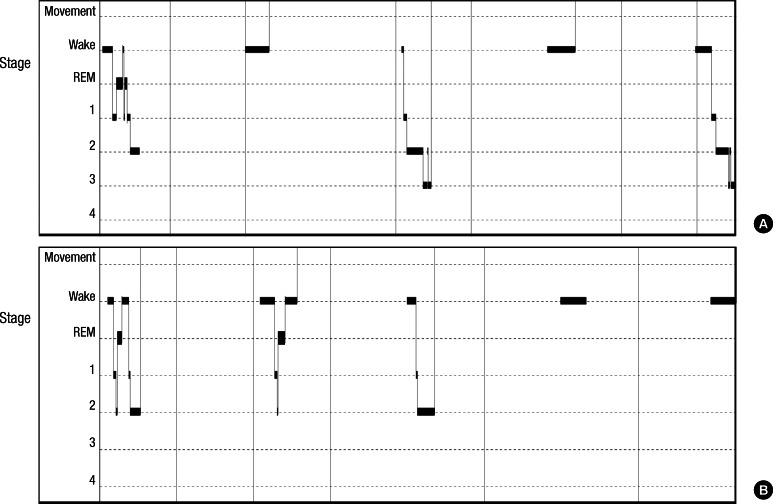

Her mother denied any history of cataplexy and it was difficult to verify the presence of hypnogogic or hypnopompic hallucinations or sleep paralysis because she was too young to understand and describe those symptoms. Neither her birth history nor past medical history was remarkable. On physical examination, her blood pressure was 115/75 mm Hg, her pulse rate was 65 beats per min, and her respiratory rate was 23. She was 112 cm in height and 19 kg in weight, and her BMI was 17.2 (40 percentile for her age). Her nares and nasal septum were within normal limits. She had kissing tonsils and edematous uvula. OSA was suspected, and she underwent overnight polysomnography (PSG) from 21:00 to 07:30, which demonstrated an apnea/hypopnea index of 5.2 and the minimum oxygen saturation of 88%. The following day, multiple sleep latency tests (MSLT) were performed at two hours interval from 09:00, the study showed a mean sleep latency of 3.5 min and one sleeponset REM period (SOREMP) (Fig. 1A). On this basis, the patient was diagnosed with OSA and was referred to otolaryngology for surgical evaluation.

Fig. 1.

The first and follow up MSLT of the subject. (A) The first MSLT showed a mean sleep latency of 3.5 min and one sleep-onset REM period. (B) Follow up MSLT showed the mean sleep latency of 8 min and two sleep-onset REM periods.

After tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy (T&A), her sleep became much calmer, snoring was eliminated, and daytime somnolence decreased. At one-month follow-up, her mother was satisfied with the outcome of the surgery but worried about persistent hypersomnia even though enough sleep at night. Since the child still took a nap for more than three hours in the kindergarten and at home, a follow-up sleep test was conducted. She underwent another overnight PSG followed by MSLT, which showed no sleep apnea but the mean sleep latency of 8 min and two SOREMPs (Fig. 1B). Diagnosis of OSA to be effectively treated by T&A and narcolepsy without cataplexy was confirmed. She started taking modafinil 100 mg per day but she was still sleepy during daytime and complained of sleep disturbance at night such as sleep onset delay and night wakings. The medication was changed into methylphenidate 10 mg per day, and the child was allowed to have a short (less than 30-min) nap around 13:00. After that, daytime somnolence and sleep disturbance were much improved and she has relatively good quality of life with stable daily activities.

DISCUSSION

Narcolepsy is rarely diagnosed in children of preschool age, and it is frequently misdiagnosed as another psychiatric, neurologic, or behavioral disease in children (3, 4). Approximately 60% of the narcoleptics suffer from cataplexy (5), but children do not often exhibit this symptom, so narcolepsy is most often shown in children as isolated hypersomnolence (6).

EDS can be an observation suggesting nocturnal sleep disorders, and the impact of insufficient or inadequate sleep, including behavioral, cognitive and emotional regulation, is evident at any age and is especially remarkable during childhood. Daytime symptoms of sleep problems in children of preschool and school age are more likely to manifest themselves as attention deficit, hyperactivity, or externalizing behaviors that are stimulus-seeking acting and high levels of physical activity to stay awake (7). While sleep-disordered breathing usually causes behavioral impairments including EDS (8, 9), it is more likely to be accompanied by those symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity (10).

OSA is a relatively common sleep disorder and its prevalence in the pediatric population is estimated at about 1%-2% (1). OSA in children is most often associated with adenotonsillar hypertrophy. Diagnostic PSG is the current gold standard and should be used in most cases of suspected OSA. T&A therapy has generally been considered excellent (11) and is now considered the best option for most children with OSA (12). Regarding narcoleptics with comorbid OSA, some studies showed that the prevalence of OSA in narcoleptics was low (2); on the other hand, Sansa et al. (13) reported that OSA occurred frequently in narcoleptics. While an increased BMI can be a risk factor of OSA in narcoleptics (14, 15), there were some reports that narcolepsy was also correlated with obesity in young children (6) and that obesity-related OSA can occur in the population (16, 17). As can be seen in this case, narcolepsy and OSA may coexist in a single patient who is not obese; however, the presence of prominent evidences of OSA, such as severe snoring or apneic episodes, and the absence of cataplexy may interfere with the diagnosis of narcolepsy, especially in children (18).

PSG with MSLT is the most important tool for diagnosis of OSA and narcolepsy. When MSLT shows a mean sleep latency less than or equal to 8 min and more than two SOREMPs, diagnosis of narcolepsy is confirmed. In addition, PSG is needed to exclude other sleep disorders, such as OSA and periodic limb movement disease (PLMD). In adults, the diagnosis of OSA is established with the apnea-hypopnea index greater than or equal to 5 symptoms, such as EDS, fatigue, non refreshing sleep, awakening with gasping or choking, and loud snoring or breathing pauses during sleep. But the diagnosis of pediatric sleep apnea is confirmed with the apnea-hypopnea index greater than or equal to 1 symptom. Younger narcoleptics are noted to have more SOREMPs and a lower mean sleep latency (19); on the other hand, prepubertal ones failed to meet MSLT diagnostic criteria (6). So repeated sleep tests may be required (20).

In conclusion, narcolepsy may be difficult to diagnose in young children, so careful history taking and serial sleep tests including MSLT may enable early recognition and treatment of the disease. In addition, those young children who are suspected of OSA accompanied by excessive daytime sleepiness rather than by inattention or hyperactivity may undergo MSLT, and it is necessary to see that those symptoms are improved with proper treatment. It is believed that although the results of MSLT are inconsistent with the diagnosis of narcolepsy, follow-up testing is necessary when the condition is clinically suspected. This case report is made along with literature review since there is no report on narcolepsy accompanied by OSA in young Korean children.

References

- 1.François G, Culée C. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in infants and children. Arch Pediatr. 2000;7:1088–1102. doi: 10.1016/s0929-693x(00)00319-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kales A, Cadieux RJ, Soldatos CR, Bixler EO, Schweitzer PK, Prey WT, Vela-Bueno A. Narcolepsy-cataplexy: I. clinical and electrophysiologic characteristics. Arch Neurol. 1982;39:164–168. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1982.00510150034008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macleod S, Ferrie C, Zuberi SM. Symptoms of narcolepsy in children misinterpreted as epilepsy. Epileptic Disord. 2005;7:13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stores G. The protean manifestations of childhood narcolepsy and their misinterpretation. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48:307–310. doi: 10.1017/S0012162206000661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sand T, Schrader H. Narcolepsy and other hypersomnias. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2009;129:2007–2010. doi: 10.4045/tidsskr.08.0655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aran A, Einen M, Lin L, Plazzi G, Nishino S, Mignot E. Clinical and therapeutic aspects of childhood narcolepsy-cataplexy: a retrospective study of 51 children. Sleep. 2010;33:1457–1464. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.11.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hansen DE, Vandenberg B. Neuropsychological features and differential diagnosis of sleep apnea syndrome in children. J Clin Child Psychol. 1997;26:304–310. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2603_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Urschitz MS, Eitner S, Guenther A, Eggebrecht E, Wolff J, Urschitz-Duprat PM, Schlaud M, Poets CF. Habitual snoring, intermittent hypoxia, and impaired behavior in primary school children. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1041–1048. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-1145-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guilleminault C, Quo SD. Sleep-disordered breathing: a view at the beginning of the new Millennium. Dent Clin North Am. 2001;45:643–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melendres MC, Lutz JM, Rubin ED, Marcus CL. Daytime sleepiness and hyperactivity in children with suspected sleep-disordered breathing. Pediatrics. 2004;114:768–775. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suen JS, Arnold JE, Brooks LJ. Adenotonsillectomy for treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in children. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:525–530. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890050023005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell RB, Kelly J. Outcome of adenotonsillectomy for obstructive sleep apnea in children under 3 years. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132:681–684. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sansa G, Iranzo A, Santamaria J. Obstructive sleep apnea in narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2010;11:93–95. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schuld A, Hebebrand J, Geller F, Pollmächer T. Increased body-mass index in patients with narcolepsy. Lancet. 2000;355:1274–1275. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74704-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perriol MP, Cartigny M, Lamblin MD, Poirot I, Weill J, Derambure P, Monaca C. Childhood-onset narcolepsy, obesity and puberty in four consecutive children: a close temporal link. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2010;23:257–265. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2010.23.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wasilewska J, Jarocka-Cyrta E, Kaczmarski M. Narcolepsy, metabolic syndrome and obstructive sleep apnea syndrome as the causes of hypersomnia in children: report of three cases. Adv Med Sci. 2007;52:207–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kotagal S, Hartse KM, Walsh JK. Characteristics of narcolepsy in preteenaged children. Pediatrics. 1990;85:205–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dauvilliers Y, Gosselin A, Paquet J, Touchon J, Billiard M, Montplaisir J. Effect of age on MSLT results in patients with narcolepsy-cataplexy. Neurology. 2004;62:46–50. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000101725.34089.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore M, Allison D, Rosen CL. A review of pediatric nonrespiratory sleep disorders. Chest. 2006;130:1252–1262. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.4.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]