Abstract

AIM: To revealed the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection in the Bhutanese population.

METHODS: We recruited a total of 372 volunteers (214 females and 158 males; mean age of 39.6 ± 14.9 years) from three Bhutanese cities (Thimphu, Punaka, and Wangdue). The status of H. pylori infection was determined based on five different tests: the rapid urease test (CLO test), culture, histology, immunohistochemistry (IHC), and serum anti H. pylori-antibody.

RESULTS: The serological test showed a significantly higher positive rate compared with the CLO test, culture, histology and IHC (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P = 0.01, and P = 0.01, respectively). When the subjects were considered to be H. pylori positive in the case of at least one test showing a positive result, the overall prevalence of H. pylori infection in Bhutan was 73.4%. The prevalence of H. pylori infection significantly decreased with age (P < 0.01). The prevalence of H. pylori infection was lower in Thimphu than in Punakha and Wangdue (P = 0.001 and 0.06, respectively). The prevalence of H. pylori infection was significantly higher in patients with peptic ulcers than in those with gastritis (91.4% vs 71.3%, P = 0.003).

CONCLUSION: The high incidence of gastric cancer in Bhutan may be attributed to the high prevalence of H. pylori infection.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Bhutan, Prevalence

Core tip: The high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection in Bhutan may contribute to the high incidence of peptic ulcers and gastric cancer. The prevalence of H. pylori infection in the capital city, Thimphu, was significantly lower than that of other rural areas. Therefore, performing eradication therapy of H. pylori and improving the sanitary conditions to decrease the rate of H. pylori infection in Bhutan can contribute to decreasing H. pylori-related diseases such as peptic ulcers and gastric cancer.

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a spiral, Gram-negative bacterium that chronically colonizes the human stomach and is currently recognized to play a causative role in the pathogenesis of various gastroduodenal diseases, including gastritis, peptic ulcers, gastric cancer, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma[1,2]. Infection with H. pylori almost always results in chronic gastritis, but only a small population of infected patients develop more severe diseases, such as peptic ulcers and gastric cancer[2,3]. In Asia, gastric cancer is still a significant health problem, and the incidence of gastric cancer geographically varies greatly. Based on the age-standardized incidence rate (ASR) of gastric cancer, Asian countries can be categorized as high-risk (e.g., Japan, South Korea and China), intermediate-risk (e.g., Vietnam) or low-risk (e.g., Thailand and Indonesia) countries for gastric cancer[4]. Although the association between H. pylori infection and gastric cancer has been well-established[5,6], a high prevalence of H. pylori infection is not always associated with a high incidence of gastric cancer. For example, despite the high infection rate in India, the incidence of gastric cancer there is low, which is known as an “Asian enigma”[7].

Bhutan is a small landlocked country in South Asia, located at the eastern end of the Himalayas and bordered on the South, East and West by India and on the North by China. The ASR of gastric cancer in Bhutan was reported to be 24.2/100000, which is relatively high among Asian countries[4]. Although several studies focused on the prevalence of H. pylori infection have been conducted in many countries with different socioeconomic, cultural, and racial groups[8-10], the prevalence of H. pylori infection in Bhutan has not been investigated yet. In this study, we first disclosed the infection rate of H. pylori in Bhutan, and the findings from this study can be used as baseline epidemiological data for further research to understand the epidemiology of H. pylori infection in Bhutan and other Asian countries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

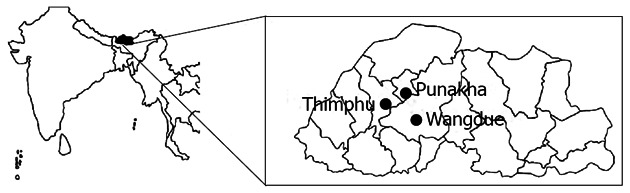

We recruited a total of 372 volunteers with dyspeptic symptoms (214 females and 158 males; mean age of 39.6 ± 14.9 years) during four days (December 6 to 9) in December 2010. The survey was conducted in Thimphu (n = 194), the capital city, and in two other cities within a 200 km radius of the capital, Punakha (n = 119) and Wangdue (n = 59) (Figure 1). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jigme Dorji Wangchuk National Referral Hospital, Bhutan.

Figure 1.

Geographic location in Bhutan.

During each endoscopy session, four gastric biopsy specimens were obtained (three from the antrum and one from the corpus). The three specimens from the antrum were used for H. pylori culture, rapid urease test and histological examination. The specimen from the corpus was used for histological examination. Peptic ulcers and gastric cancer were identified by endoscopy, and gastric cancer was further confirmed by histopathology. Gastritis was defined as H. pylori gastritis in the absence of a peptic ulcer or gastric malignancy.

Status of H. pylori infection

To maximize the diagnostic accuracy, 5 different methods were combined for the diagnosis of H. pylori infection, including culture, histology, immunohistochemistry (IHC), the rapid urease test and serum H. pylori antibody. For the H. pylori culture, one biopsy specimen from the antrum was homogenized in saline and inoculated onto Mueller Hinton II Agar medium (Becton Dickinson, NJ, United States) supplemented with 7% horse blood without antibiotics. The plates were incubated for up to 10 d at 37 °C under microaerophilic conditions (10% O2, 5% CO2 and 85% N2). H. pylori was identified on the basis of colony morphology, Gram staining and positive reactions for oxidase, catalase, and urease. Isolated strains were stored at -80 °C in Brucella Broth (Difco, NJ, United States) containing 10% dimethylsulfoxide and 10% horse serum. For histology, all biopsy materials were fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 24 h and then embedded in paraffin. Serial sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and with May-Giemsa stain. The state of the gastric mucosa was evaluated according to the updated Sydney system[11]. The degree of the bacterial load was classified into four grades: 0, “normal”; 1, “mild”; 2, “moderate”; and 3, “marked”. A bacterial load grade greater than or equal to 1 was defined as H. pylori positive. H. pylori seropositivity was evaluated with a commercially available ELISA kit (Eiken Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Patients were considered to be H. pylori-negative when all five tests were negative, and a H. pylori-positive status required at least one positive test result.

Immunohistochemistry

IHC was performed as described previously[12]. Briefly, after antigen retrieval and inactivation of endogenous peroxidase activity, tissue sections were incubated with the α-H. pylori Ab (DAKO, Denmark) overnight at 4 °C. After washing, the sections were incubated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Nichirei Co., Japan), followed by incubation with a solution of avidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (Vectastain Elite ABC kit; Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, United States). Peroxidase activity was detected using a H2O2/diaminobenzidine substrate solution. For all cases, we performed Giemsa staining using a serial section to identify the presence of H. pylori. If the H. pylori identified by Giemsa staining was found to be positively immunostained, we judged the case to be positive.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis were conducted using the chi-square test to compare discrete variables and Cochran-Armitage analysis to compare the prevalence of H. pylori infection. Differences in the prevalence in each group were analyzed using the Mantel-Haenszel method. To match age and sex, multiple backward stepwise logistic regression analyses were used to examine the associations of peptic ulcers with the main predictor variables. The predictor variables for peptic ulcers were age, sex and H. pylori status. For each variable, the OR and 95%CI were calculated. Differences at P < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. The data analysis was performed using JMP® 9 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States) and SPSS version 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States).

RESULTS

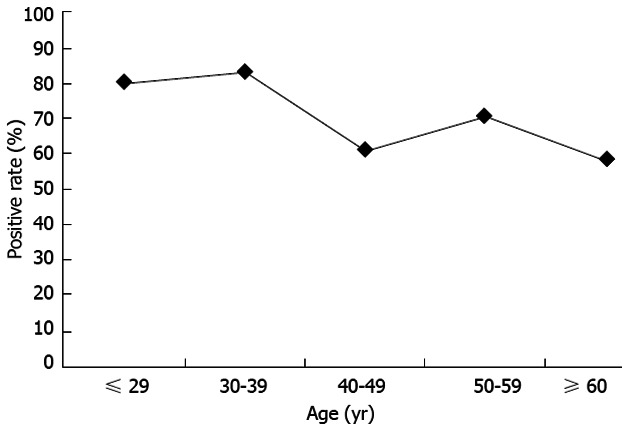

A total of 372 subjects were recruited, comprising 107 who were ≤ 29 years old, 96 who were 30-39 years old, 80 who were 40-49 years old, 45 who were 50-59 years old, and 44 who were ≥ 60 years old. Table 1 shows the H. pylori-positive rate for each test. The serological test showed a significantly higher positive rate compared with the CLO test, culture, histology and IHC (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, P = 0.01, and P = 0.01, respectively). The prevalence of H. pylori infection by the serological test was as follows: 74.8% (80/107) for the ≤ 29 years old group, 83.3% (80/96) for the 30-39 years old group, 58.8% (47/80) for the 40-49 years old group, 66.7% (30/45) for the 50-59 years old group, and 54.5% (24/44) for the ≥ 60 years old group. When the subjects were considered to be H. pylori positive in the case of at least one positive test, the prevalence of H. pylori was 80.4% (86/107) for the ≤ 29 years old group, 83.3% (80/96) for the 30-39 years old group, 61.3% (49/80) for the 40-49 years old group, 71.1% (32/45) for the 50-59 years old group, and 59.1% (26/44) for the ≥ 60 years old group; thus, the prevalence was significantly decreased with age (P < 0.01). This phenomenon was significant in the Thimphu area. Because the number of subjects older than 50 years old in Punakha and Wangdue was too small for the statistical analysis, this trend was not observed in these two areas. Overall, the prevalence of H. pylori infection in Bhutan was 73.4% (273/372). Figure 2 shows the prevalence of H. pylori infection according to the various range age groups. There was no significant difference between men and women (data not shown).

Table 1.

Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in each diagnostic test n (%)

| Diagnostic test |

Age (yr) |

Total (n = 372) | ||||

| ≤ 29 (n = 107) | 30-39 (n = 96) | 40-49 (n = 80) | 50-59 (n = 45) | ≥ 60 (n = 44) | ||

| Serum | 80 (74.8) | 80 (83.3) | 47 (58.8) | 30 (66.7) | 24 (54.5) | 261 (70.2) |

| CLO | 68 (63.6) | 59 (61.5) | 35 (43.8) | 24 (53.3) | 17 (38.6) | 203 (54.6) |

| Culture | 72 (67.3) | 61 (63.5) | 38 (47.5) | 23 (51.1) | 16 (36.4) | 210 (56.5) |

| Histology | 77 (72.0) | 64 (66.7) | 41 (51.3) | 28 (62.2) | 19 (43.2) | 229 (61.6) |

| IHC | 77 (72.0) | 64 (66.7) | 41 (51.3) | 28 (62.2) | 19 (43.2) | 229 (61.6) |

| Final | 86 (80.4) | 80 (83.3) | 49 (61.3) | 32 (71.1) | 26 (59.1) | 273 (73.4) |

CLO: The rapid urease test; IHC: Immunohistochemistry.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection by age group in Bhutan.

The prevalence of H. pylori infection in the three cities was analyzed by the Mantel-Haenszel method to adjust for age. It differed among the three cities, with the highest in Punakha (102/119, 85.7%), followed by Wangdue (44/59, 74.5%) and Thimphu (127/194, 65.4%). The prevalence of H. pylori infection was significantly lower in Thimphu than in Punakha even after the adjustment for age (P = 0.001). Although there was no significant difference, the prevalence tended to be lower in Thimphu than in Wangdue even after the adjustment for age (P = 0.06).

In the endoscopic diagnosis, gastritis was the most common finding (307/372, 82.5%). Gastric and duodenal ulcers were found in 25 (6.7%) and 22 (5.9%) cases, respectively. Gastric cancer was found in 5 cases (1.3%). Duodenal erosion, duodenal tumor, and reflux esophagitis were found at 5, 1 and 7 cases, respectively. Table 2 shows the prevalence H. pylori infection in each diagnosis. A high infection rate was detected among patients with gastric ulcers (92.0%) and duodenal ulcers (90.9%). In addition, 71.3% of the subjects with gastritis were H. pylori-positive. When gastric and duodenal ulcers were defined as peptic ulcers, the prevalence of H. pylori infection in peptic ulcers was significantly higher than that in gastritis (91.4% vs 71.3%, P = 0.003). The percentage of men was also significantly higher in patients with peptic ulcers than in those with gastritis (72.3% vs 37.1%, P < 0.001). Multiple logistic analysis after adjusting for age and gender showed that H. pylori-positivity in addition to male gender was significantly associated with peptic ulcers (OR = 3.89, 95%CI: 1.33-11.33).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in each diagnosis n (%)

| Diseases | n | Positive |

| Gastritis | 307 | 219 (71.3) |

| Gastric ulcer | 25 | 23 (92.0) |

| Duodenal ulcer | 22 | 20 (90.9) |

| Gastric cancer | 5 | 3 (60.0) |

| Duodenal erosion | 5 | 3 (60.0) |

| Duodenal tumor | 1 | 1 (100.0) |

| Reflux esophagitis | 7 | 4 (57.1) |

DISCUSSION

We first revealed that the prevalence of H. pylori in Bhutan was 73.4%. In contrast with developed countries, H. pylori infections occur earlier in life and with a higher frequency in the developing world[8]. The prevalence of infection with H. pylori infection exceeds 50% by 5 years of age, and by adulthood, infection rates exceeding 90% are not unusual in developing countries[13]. Although the prevalence of infection has dropped significantly in many parts of North America, Western Europe and Asia, no such decline has been noted in the developing world[13]. The present study showed that a high prevalence was detected in younger age groups and that the prevalence significantly decreased with age in Bhutan. The decrease in the H. pylori infection rate with age might be due to the overuse of antibiotics in Bhutan. Antibiotics are frequently used in any infectious diseases in Bhutan (Dr. Lotay, personal communication). Even under these conditions, the prevalence of H. pylori infection was relatively high in all age groups.

Several clinical tests have been developed to diagnose H. pylori infection. However, there is still no established “gold standard” for the diagnosis of H. pylori, and thus the combination of two or more tests should be applied to determine the accurate prevalence of infection. In this study, we combined 5 different tests and considered H. pylori-positivity to be at least one positive test among the five tests. In this study, the serological test showed the highest positive rate compared with the other 4 tests. Although the serological test is widely used in epidemiological studies and not affected by local changes in the stomach that could lead to false-negatives, as in the other tests, this test cannot distinguish between current and past infections because H. pylori IgGs persist even after the disappearance of this bacterium[9,14]. Therefore, results that are positive in the serological test and negative in the endoscopic tests may indicate a past infection. Culture from biopsy specimens has the potential of leading to a high sensitivity, given that only one bacterium can multiply and provide billions of bacteria. However, both strict transport conditions and careful handling in the laboratory are necessary[14]. Histopathological positivity depends on the density of H. pylori biopsy sites; thus, these tests can occasionally show false negative results[14]. In addition, the histological diagnosis of H. pylori infection is very much dependent on the expertise of the pathologists. The rapid urease test, such as the CLO test, can be useful as a rapid diagnostic method. However, these results can also be affected by the bacterial load[14]. A high proportion of the elderly population develops gastric atrophy and intestinal metaplasia, which can lead to a hostile environment for H. pylori and thus fewer bacteria and potentially a negative result. A detailed study in histological scoring is necessary for further study. Moreover, endoscopic tests, including the CLO test, culture and histological examination, can be affected in bleeding patients with peptic ulcers[10]. However, although the reason is not clear, all peptic ulcer cases in our study were not in the active bleeding phase, indicating that we do not need to consider any effects of bleeding.

The lowest infection rate was found in Thimphu, which is the capital city of Bhutan. The prevalence of H. pylori infection in Thimphu was significantly lower than that of the rural cities of Punakha and Wangdue. In Thimphu, the sanitary conditions are better than those of Punakha and Wangdue, which supports the possibility that sanitary conditions may be important factors for H. pylori infection. In fact, the prevalence of H. pylori infection was very low in individuals less than 10 years old (i.e., approximately 5%) and increased with age in Japan[15]. Overall, it was higher among individuals born before 1950 and lower in those born thereafter. There was a rapid change in the sanitary conditions and standard of living in Japan after World War II, and clean public water systems were introduced in Japan in the 1950s. Therefore, sanitary conditions, such as a full equipment rate of water and sewage, are considered to be important factors for H. pylori infection[8].

The prevalence of H. pylori in patients with peptic ulcers was significantly higher than that in patients with gastritis, which is consistent with previous reports[16-18]. This observation suggests that H. pylori infection is a risk factor for the development of peptic ulcers and gastric cancer, even in Bhutan. In addition, we found 5 gastric cancer patients among the 372 volunteers. The ASR of gastric cancer in Bhutan was reported to be 24.2/100000 based on the small number in the registry (114 cases) in 2008[4]. This observation supports the high incidence of gastric cancer in Bhutan.

In conclusion, the high incidence of gastric cancer in Bhutan may be attributed to the high prevalence of H. pylori infection. Therefore, the eradication therapy of H. pylori can contribute to a decrease in H. pylori-related diseases, such as peptic ulcers and gastric cancer. However, we should be cautious regarding eradication therapy in Bhutan. Even when eradication therapy for H. pylori has succeeded, the infection frequently recurs in patients in developing countries, where there is a high prevalence of H. pylori infection[19]. Such repeat infections are either due to a recurrence of the original infection or reinfection with a new strain. Improving the sanitary conditions to decrease the prevalence of H. pylori in Bhutan is important.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kudo Y, Yano K and Chaithongrat S for their technical assistance.

COMMENTS

Background

Bhutan is a small landlocked country in South Asia and the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection in Bhutan has not been investigated.

Research frontiers

The prevalence of H. pylori in Bhutan was 73.4% and the high incidence of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer disease in Bhutan may be attributed to the high prevalence of H. pylori infection.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This is the first study exploring the extremely high prevalence of H. pylori infection in Bhutan. Many tests for H. pylori detection such as serological test rapid urease test, culture, histology and immunohistochemistry were performed and analyzed.

Applications

The study results suggest that high incidence of gastric cancer and peptic ulcer disease in Bhutan may be attributed to the high prevalence of H. pylori infection. Therefore, H. pylori eradication therapy can contribute to reduce these H. pylori-related diseases.

Peer review

This is a study in which authors analyzed the prevalence of H. pylori infection in different cities, age group and each disease. The results are very interesting and suggest that H. pylori eradication and improve of sanitation should be considered to reduce H. pylori infection and related diseases in Bhutan.

Footnotes

Supported by A Grant from the grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, No. 23790798; A Grant from the National Research University Project of the Thailand Office of Higher Education Commission; The National Institutes of Health (DK62813) and the grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, No. 22390085 and No. 22659087

P- Reviewer Yen HH S- Editor Wen LL L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

References

- 1.Peek RM, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:28–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1175–1186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra020542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox JG, Wang TC. Inflammation, atrophy, and gastric cancer. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:60–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI30111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, Chang Y, Vogelman JH, Orentreich N, Sibley RK. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127–1131. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110173251603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miwa H, Go MF, Sato N. H. pylori and gastric cancer: the Asian enigma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1106–1112. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goh KL, Chan WK, Shiota S, Yamaoka Y. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and public health implications. Helicobacter. 2011;16(Suppl 1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00874.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azevedo NF, Huntington J, Goodman KJ. The epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori and public health implications. Helicobacter. 2009;14(Suppl 1):1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2009.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tonkic A, Tonkic M, Lehours P, Mégraud F. Epidemiology and diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2012;17(Suppl 1):1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2012.00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dixon MF, Genta RM, Yardley JH, Correa P. Classification and grading of gastritis. The updated Sydney System. International Workshop on the Histopathology of Gastritis, Houston 1994. Am J Surg Pathol. 1996;20:1161–1181. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199610000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uchida T, Kanada R, Tsukamoto Y, Hijiya N, Matsuura K, Yano S, Yokoyama S, Kishida T, Kodama M, Murakami K, et al. Immunohistochemical diagnosis of the cagA-gene genotype of Helicobacter pylori with anti-East Asian CagA-specific antibody. Cancer Sci. 2007;98:521–528. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frenck RW, Clemens J. Helicobacter in the developing world. Microbes Infect. 2003;5:705–713. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(03)00112-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mégraud F, Lehours P. Helicobacter pylori detection and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:280–322. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00033-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Asaka M, Kimura T, Kudo M, Takeda H, Mitani S, Miyazaki T, Miki K, Graham DY. Relationship of Helicobacter pylori to serum pepsinogens in an asymptomatic Japanese population. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:760–766. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90156-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T, et al. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646–664. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Hunt RH. Role of Helicobacter pylori infection and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in peptic-ulcer disease: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2002;359:14–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07273-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papatheodoridis GV, Sougioultzis S, Archimandritis AJ. Effects of Helicobacter pylori and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on peptic ulcer disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:130–142. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2005.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rimbara E, Fischbach LA, Graham DY. Optimal therapy for Helicobacter pylori infections. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:79–88. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2010.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]