Abstract

Aim

Improving community health worker's performance is vital for an effective health system in developing countries. In Malawi, hardly any research has been done on factors that motivate this cadre. This qualitative assessment was undertaken to identify factors that influence motivation and job satisfaction of health surveillance assistants (HSAs) in Mwanza district, Malawi, in order to inform development of strategies to influence staff motivation for better performance.

Methods

Seven key informant interviews, six focus group discussions with HSAs and one group discussion with HSAs supervisors were conducted in 2009. The focus was on HSAs motivation and job performance. Data were supplemented with results from a district wide survey involving 410 households, which included views of the community on HSAs performance. Qualitative data were analysed with a coding framework, and quantitative data with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS).

Results

The main satisfiers identified were team spirit and coordination, the type of work to be performed by an HSA and the fact that an HSA works in the local environment. Dissatisfiers that were found were low salary and position, poor access to training, heavy workload and extensive job description, low recognition, lack of supervision, communication and transport. Managers and had a negative opinion of HSA perfomance, the community was much more positive: 72.9% of all respondents had a positive view on the performance of their HSA.

Conclusion

Activities associated with worker appreciation, such as performance management were not optimally implemented. The district level can launch different measures to improve HSAs motivation, including human resource management and other measures relating to coordination of and support to the work of HSAs.

Introduction

Malawi is one of the countries facing challenges in human resources for health. The Government of Malawi started an Emergency Human Resources Programme (EHRP) in 2005, with the main aim to enhance the size and capacity of the health workforce1,2. Enhancing a health status of a population via delivery of high-quality health services requires sufficient numbers of qualified health personnel, who are kept motivated to perform their jobs in an effective and efficient way.

Motivation in the work context is defined as “an individual's degree of willingness to exert and maintain an effort towards an organisation's goals”3. If factors that contribute to motivation are known, this can give input to human resource management (HRM) policies. With proper HRM policies and interventions that are tailored to a certain cadre or organisation, the motivation of health workers could be improved and thus job performance.

According to Herzberg's theory of motivation at the workplace, there are two types of motivating factors:

Satisfiers: the main causes for job satisfaction. These involve, for example, achievements, recognition, responsibility and the work itself.

Dissatisfiers: the main causes of job dissatisfaction. These involve factors such as working conditions, salary, relationships with colleagues and administrative supervision that are seen as insufficient or absent. Despite centralized HRM in the Malawian public health sector, district hospitals have ample opportunity to influence satisfiers and dissatisfiers through performance management: the “measuring, monitoring and enhancing of the performance of staff”5. For example, at the district level, proper supervision and clear job descriptions should be provided to health workers.

Problems such as health workers shortages, lack of finances, and excessive workload make the working environment at district level difficult. In Malawi, research has been done on factors that influence job satisfaction of mostly mid-level clinical and nursing staff. Factors that have been found to contribute to low staff motivation include inadequate and inequitable remuneration, lack of recognition, overwhelming responsibilities and workload with limited resources, lack of a stimulating working environment, inadequate supervision or supervision which is negative in nature and without feedback, the impact of HIV and AIDS, poor access to training and limited career progression and lack of transparency in the recruitment of staff. There is a need for a stronger HRM at district level to improve worker motivation and performance6–13. Little research has been done on aspects influencing motivation of staff within the preventive health sector in Malawi14. Health Surveillance Assistants (HSAs), 10,507 in number in 200915, constitute the largest workforce in all districts of Malawi . They are salaried Community Health Workers (CHWs), responsible for preventive health, but also for several curative health services. In the 1960's, temporary staff, “smallpox vaccinators” were recruited and in the 1970s “cholera assistants” were mobilised. From this, the HSAs evolved and were officially part of the health system since 1995. At the time of the assessment, the HSAs general job description was: “a primary health care worker engaged in community based health related services. He or she is a first level health provider and serves as an important link between the health facility and the community that he/she serves”16. They are supposed to be assisted by village health committees (VHCs, which normally consist of 10 volunteers at village level). They are deployed in a community setting and each HSA has an assigned catchment area. The Malawi Secondary Certificate Examinations (MSCE) or Junior Certificate (JCE) are the minimum requirements to obtain employement as an HSA and an eight weeks training programme from the Ministry of Health. HSAs are part of the Environmental Health Department within the Ministry. The department consists of different cadres of staff, from management (District Environmental Health Officer, DEHO) to environmental health officers (EHOs) at supervisory and programme levels. The HSA cadre has had a growing repertoire of tasks, partly as a result of task shifting17–19. Nowadays, the (full-time) job consists of: conducting community assessments; promotion of hygiene and sanitation by village and business inspections and feedback to the community; formation, training and supervision of VHCs; health education on different topics; promotion and delivery of the Accelerated Child Survival and Development (ACSD) of under five children; provision of immunizations, vitamin A, de-worming drugs; growth monitoring of under 5 children and giving tetanus vaccination to women of child bearing age; disease surveillance and responding to disease outbreaks; monitoring of safe water supply; chlorination of water; conducting village clinics on specified days for treatment of minor ailments (and referring severe cases to the nearest health facility); promotion of vector and vermin control at the household level and provision of reproductive health services.

On top of this, HSAs are supposed to record all kinds of data in various registers (Village Health Registers (VHRs), Health Management Information System (HMIS) registers and registers of specific programmes). They have to write monthly work plans and reports. They can be asked to perform any other duties deemed reasonable by the supervisor. For example, specific programmes conducted by Non Governmental Organisations (NGOs) are often implemented by HSAs.

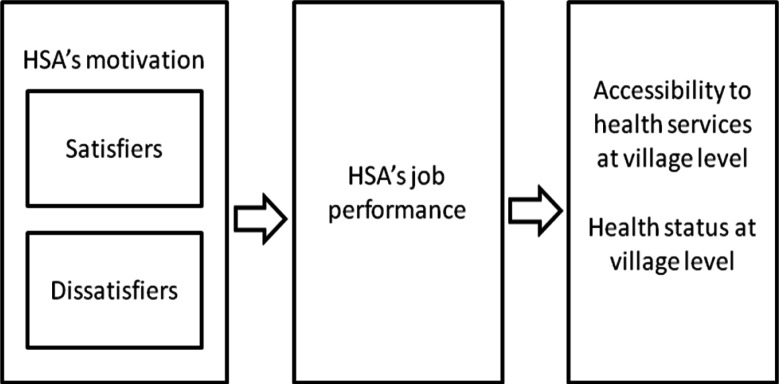

With adequate performance of HSAs, it can be assumed that there would be fewer health problems at the village level (as a result of preventive measures) or health problems are resolved at village level, resulting in a decreased patient burden in hospitals. The relationship between satisfiers and dissatisfiers, HSAs motivation and job performance and the implications on access to health services at the village level and community health status is represented in figure 1.

Fig1.

We are aware of only one study (Kadzamira and Chiowa 2001) that explored the various constraints hindering motivation and job performance of HSAs in Malawi, particularly related to immunisation services20. The constraints reported by the HSAs were poor remuneration, no promotion and low status given to HSAs in the civil services, transport problems, irregular supply of vaccines and drugs and lack of protective clothing and stationery. Nineteen percent (n=23) of the HSAs in the study were untrained and supervision was reported to be inadequate and irregular due to mobility problems. Furthermore, there were limited and irregular refresher courses and poor telecommunication systems. Another important factor that resulted in low motivation of HSAs was the weak position of prevention (compared to curative services) within the health system. It was perceived that prevention services received less attention over the past years and that resources were shifted to curative services. In general, it was found that HSAs had a heavy work load, especially in rural areas. The average population being served by the sampled HSAs was 2,364 people. At that time, the recommendation from the Ministry of Health was between 2,000 and 2,500 people (about 10 villages) per HSA. Currently the recommendation is 1,000 people per HSA.

This paper reports on a qualitative assessment on motivation, job perception and satisfaction of HSAs conducted in Mwanza district in southern Malawi. In addition to the perception of HSAs on satisfiers and dissatisfiers regarding their job, perceptions of managers and the community on HSA's performance were part of the research. In Mwanza, 61% of the people live below the poverty line21. The district has a high burden of preventable diseases like malaria and diarrhoea. Mwanza District Hospital is the only hospital in the district and offers preventive and curative services for a population of 97,883 (2011)22. There are three rural health centres in the district, which offer basic health and maternity care. The assessment on 80 HSAs was done in 2009, as the start of a programme led by the management of the hospital and Voluntary Services Oversees (VSO) to improve job performance of HSAs as a reaction to perceived inconsistency in quality of services provided by HSAs.

Methods

The assessment was qualitative and exploratory in nature. A team of two researchers explored the role and the work of HSAs in Mwanza district by conducting field visits and observing the work of the HSAs. Seven key informant interviews about the work of the HSAs, motivation issues and performance were conducted with the District Health Officer (DHO), District Medical Officer (DMO), the DEHO (the line manager of all HSAs), the District Nursing Officer (DNO) and three senior HSAs (the coordinators amongst the HSAs). These interviews gave input for a participatory assessment and planning activity that was conducted with all of the 80 HSAs in the district, in June 2009. The activity consisted of focus group discussions with HSAs on the following subjects: tasks and responsibilities, challenges in work, successes in work and planning way forward. In total, six groups of about thirteen HSAs each participated in this activity. The findings of the focus group discussions were analysed through a coding framework categorising satisfiers and dissatisfiers, and data summaries were made. These were discussed with eight Environmental Health Officers and the DEHO and fed back to the HSAs for validation. In 2010, a district wide primary health care survey was conducted to identify factors influencing performance of HSAs other than the satisfiers and dissatisfiers reported by HSAs themselves. From this survey, insight was given into the knowledge of people at village level on the HSAs job and their perceptions on HSAs performance, related to contextual factors, like the situation of the village and residence of the HSA. In the survey, 410 community members at the household level were interviewed on all kinds of health issues, after giving an oral informed consent. The questionnaire was pre-tested in two villages, and adjusted afterwards. The survey covered the catchment areas of 24 HSAs in Mwanza district and the 24 villages were stratified as rural or urban areas and villages where the HSA was living or not living (both 50%-50%). The selected villages covered the whole geographical area of the district. A total of 410 households were included and selected randomly. About seventeen heads of the household or adults within the household in each village were randomly selected. Interviews were conducted by four data clerks who underwent a one day interview training particular to this study. The quantitative data were analyzed with the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (Version 17). Significance tests were done by Pearson's χ2; p<0.05 was considered significant. Ethical approval was not obtained for this study, as it was a programme audit and the implemented research was aimed at informing district policy and planning purposes.

Results

Views of management on HSA's job and performance

Mwanza has 80 HSAs for a population of 97,883 which makes the people served by one HSA around 1,224. While it was observed on the one hand by key informants that the work load of HSAs was large, on the other hand they saw HSAs as lazy and low performing. One key informant said: “HSAs should work much harder. They should be found in their village all the time.” The job description was not widely known among other key informants than the DEHO. Constraints in the work of HSAs that were mentioned most were lack of transport and training.

HSA's perception of satisfiers and dissatisfiers

During the focus groups discussions with the HSAs of Mwanza district, satisfiers and dissatisfiers were discussed. The satisfiers that were most prominent were:

Team spirit and coordination

The type of work: especially immunizations, health talks.

Knowledge of and working in the local environment

Dissatisfiers were discussed in 12 small groups, using problem trees. At the end, all problems and constraints were discussed in six focus groups and the most important dissatisfiers were identified (box 1).

Box 1. Dissatisfiers for HSAs in Mwanza district.

Salary and position

Salary is low and not based on qualifications

No opportunity to promotion

Training

No refresher courses available

Favouritism for selection of HSAs to attend workshops

The job

Heavy workload

Involvement in activities other than in job description

Social

Low recognition of HSAs from other staff and management, supervisory level/ HSA has no voice

Social problems of living in a remote area

Educational status of target group (the community) resulting in problems, like lack of basic knowledge on hygiene

Absent or inadequate organized VHCs

Communication and supervision

Poor communication between health staff at different levels: from health centre to district hospital (no feedback, no regular meetings, no work plans and reports)

Lack of a supervision system with clear criteria

Other factors of concern

Transport problems (availability of transport, fuel, possibility for maintenance)

Poor roads, telecommunication

Lack of uniforms/ protective clothing

Poor housing

Salary and position

The majority of HSAs were dissatified with salaries. There was no difference in salary between a person with an MSCE or JCE certificate. Furthermore, the position of a senior HSA was not clear. According to the focus group participants, they seemed to have a role in supervision, acting as a kind of team leader of a group of HSAs, but nobody really knew the difference between a “regular” HSA and a senior HSA. There was no difference in salary reported either. The years of service of an HSA also didn't influence the amount of the salary. HSAs also realised that hardworking and non-hard working HSAs were paid the same salary, and that would be nothing would be done in terms of appreciation or sanctions. One of the HSAs summarized these issues as follows: “salary should be adjusted according to merit.”

Training

Some HSAs had not yet received the required eight weeks training from the Ministry of Health. They said that they were supposed to be trained “on the job”, which was difficult due to the heavy workload of other HSAs and a lack of time of supervisors. It was also found out that there was nobody specifically responsible to make sure on the job training was done. There is no official refresher course for HSAs in Malawi. There are a lot of specific trainings seminars and courses, mainly offered by NGOs when a certain intervention is going to be implemented in the district. For these sessions, a lot of HSAs had a feeling that some people are favoured for invitation, which is a sensitive issue because of the fact that per diems given by the organisers of these trainings are additions to the (perceived to be low) salary of the HSA. This problem is related to HSAs being assistants to specific programmes in the district (see below).

HSA's perception of the job

HSAs are supposed to know their job description, as they get it during the eight week training course. In practice, some of them can't state the whole job description, because since they started, new tasks were added, and they were not provided with the new job description. In general, HSAs experienced a heavy workload. The focus of the job as stated by the HSAs was water and sanitation, hygiene, growth monitoring, immunisations and health education.

Several tasks that are not specifically mentioned in the job description of an HSA but were performed by some HSAs in Mwanza were identified (box 2). For some of these roles and responsibilities, the HSA got specific training. They are seen as the assistant of the programme coordinator at district level (for example Prevention of Mother to Child transmission of HIV (PMTCT), Voluntary Counselling and Testing (VCT), dermatology, eye programme). The division of work between the one officially responsible for these tasks (nurses, clinical officers or EHOs) and the HSA was on case to case basis. Often, these HSAs had lost the community focus, which should be the first priority of the work. The work at village level was neglected because of the heavy workload of the HSA at the district hospital or health centre regarding these specific programmes.

Box 2. Tasks that HSAs in Mwanza district perform that are not in the job description.

Filling in of the Out Patient Department (OPD) HMIS register at the OPD clinic

Malaria and tuberculosis microscopy

Working in Voluntary Counseling and Testing (VCT) on HIV and PMTCT

Home Based Care (HBC)

Cleaning in hospital wards and other rooms/ surroundings

Administrating anti rabies vaccine

Treating cholera cases

Caring for patients in the wards

Diagnosing patients, administering patients

Social factors

HSAs lacked recognition from the upper level of the health system (supervisors and management). Recognition from the village level seemed not to be a problem (see below). Regarding the management level, it became clear that there was a significant feeling of undervaluation of the HSAs job. The group discussion with supervisors revealed that most supervisors recognized the importance of the HSAs job, but found the performance of HSAs low. The disconnection between HSA and supervisor resulted in a further feeling of unimportance by HSAs: “We are voiceless in this health system”.

Communication and supervision

From the focus groups and observations is was found that there was limited supervision of HSAs in Mwanza district. There were no regular visits, there was no supervision checklist with transparent criteria known by HSAs and no feedback mechanism. A system of work plans and reports to be filled in and submitted to a supervisor was not in place. The HSAs reported to find it difficult to approach a supervisor or a programme manager at the district hospital level. No regular HSAs meetings were conducted.

Other factors of concern

One of the top discouraging factors of HSAs was a lack of transport. There was a lack of motorbikes and fuel for immunization activities, push bikes for daily village visits, and spare parts. Other issues as poor roads and poor telecommunication were mentioned, as well as poor housing, often resulting in HSAs living far away from their catchment area. Another issue that was mentioned was a lack of items like bags and first aid kits.

Community perception of HSA's job and performance

A total of 410 people were interviewed at household level using a structured questionnaire. 70.5% were women, 29.5% were men. 85.6% of the respondents were farmers. 25.2% didn't have any education, 24.4% had an educational level up to standard four, 22.7% up to standard eight, 16.4% had a Primary School Leaving Certificate, 5.1% had attained a JCE, 2.9% MSCE and the rest had another kind of education.

28.5% of the interviewed persons didn't receive any form of health care in the preceeding three months (26.3% for female and 33.9% for male respondents). Amongst the people who did use health services in the past three months preceeding the interview, the under 5 clinic was the most frequently visited.

On the question whether the respondent knew the HSA, 21.2% answered negative. Significantly more respondents in the urban zone did not know the HSA than in rural zones (28.8% compared with 13.7%, χ square p<0.001) and significantly more male respondents didn't know the HSA than female respondents (28.9% compared with 18%, χ square p<0.05). Most (88.8%) respondents were able to mention at least one task of an HSA (without prompting). Significantly more female respondents than male respondents were able to mention at least one task of an HSA: 91% compared with 83.5% (χ square p<0.05). For the respondents who did not know the HSA, this was 50.6% (significant difference with respondents who knew their HSA (99.1%), χ-square p<0.001). For the different tasks of an HSA, respondents mentioned the following (without prompting): hygiene (67.8%), growth monitoring and immunisation (56.1%), health education (43.4%) and 39% specifically mentioned the provision of 1% stock solution for cleaning water. 77.9% of the respondents thought that the HSA was indeed performing these tasks; 7.7% said the HSA was not performing these tasks. 14.4% did not know whether the HSA performed these tasks. Significantly more respondents in the rural area said that the HSA was performing the tasks (83.1% compared with 72.5% in the urban area, χ-square p<0.05). The same was found for respondents living in a village where the HSA was living in or close by (83.4% compared with 72.3% for respondents living in a village where the HSA was not living in or close by, χ-square p<0.01).The difference was most significant if comparing respondents that knew/ didn't know the HSA of their village: 92.5% of respondents knowing their HSA reported that the HSA was performing his or her tasks compared with 25.9% of the respondents not knowing their HSA (χ-square p<0.001). When respondents were asked about their general feeling on the performance of the HSA, 72.9% were positive, 17.6% did not know, 6.3% were neutral and 3.2% were negative. Respondents in the rural area were significant more positive about the HSA; 79% compared with 66.8% in the urban area,χ square p<0.01. In addition, respondents living in a village where the HSA was living in or close by were significantly more positive about the HSA than respondents living in a village where the HSA was not living in or closed by (82% compared with 63.9%, χ square p<0.001) and respondents who knew the HSA were significantly more positive about the HSA than respondents who didn't know the HSA (86.1% compared with 24.1%, χ square p<0.001). Regarding the general feeling of the HSA's performance, no difference in opinion was found between female and male respondents.

Discussion

Several studies show the importance of CHWs in improving access to, and coverage of, health services. CHWs need to be carefully selected, appropriately paid, trained and supervised and continuously supported. CHWs should be embedded in the health system and supported by communities23–28. This assessment identified satisfiers and disatisfiers- factors that affect CHW's (HSA's) motivation and hence perfomance levels at work. In concordance with previous studies that have investigated motivating among health workers in developng contries,29,30 our study shows that both financial and non financial incentives strongly influence CHW motivation and retention.

The dissatisfiers found in this assessment were were similar to the discouraging factors identified in the study on the role of HSAs in Malawi by Kadzandira and Wycliffe in 200122, although the heavy workload and low recognition came out in this study much more prominently. Studies looking at motivation of CHWs in other countries identified similar satisfiers and dissatisfiers as found in this assessment and are recommending better, tailor made performance management systems31–34.

The dissatisfiers reported by HSAs in this study were partly recognised by the management. The heavy workload was recognised, as well as more practical issues like lack of transport and training. Non-financial incentives (that could increase motivation) such as recognition, attention from supervisors and good communication were much more reported by HSAs themselves as by the management. This shows that, besides salary and position issues which are regulated by the central level, there was much space for district level measures to improve HSA motivation and job performance.

The community view on performance of HSAs was found to be generally positive. The perception of the HSA's performance was more positive in rural areas. This could mean that some of the dissatisfiers (reported by the HSAs themselves) like working in a remote area, lack of transport to rural areas and lack of housing in rural areas do not necessarily resulting in a poor performance.

The household survey showed that HSAs living in urban areas were less well known and seen as performing less well as compared with HSAs in rural areas by the community respondents. A possible contributing factor could be that urban based HSAs are more often than rural based HSAs assisting in the hospital within specific programmes and sometimes neglect their community work. They more often don't reside in the village they serve. It could be that prestige is involved, as HSAs like to be involved in vertical programmes. It gives them a status and better accessibility to additional trainings and allowances. These issues are related to the dissatisfiers salary and stagnant position and lack of training identified during the focus group discussions with the HSAs.

Study limitations

This qualitative assessment had small sample sizes and the results cannot be taken as generalised results for Malawi. The study did not measure motivation and job satisfaction on a set scale: much of the data was obtained from focus group discussions. It is possible that study respondents' reports may have been inaccurate, due to, among other reasons, the desire by some respondents to conform to the group.

Recommendations

To keep the HSA workforce in Malawi motivated, several HRM and other interventions could be taken at the national and district level. The national level could take measures related to the first three categories of dissatisfiers as presented in box 2: salary and position of HSAs, training and the job of the HSA. The district level is able to take measures related all categories in box 2, except salary and position. For both levels, some measures have already been taken or under way.

National level

Salary and position

HSA salaries have increased by 26% under the EHRP15. Furthermore, efforts have been made to address the issue of salary differentiation depending on education level. HSAs that do not hold an MSCE certificate are encouraged to go back to school and get the certificate, after that they will be promoted14. Regarding financial incentives other than salary, the national level has to carefully consider on policies regarding allowances in general. Loan schemes for HSAs could be considered.

Training

In 2009 the eight weeks training for HSAs was extended to ten weeks. The national level could consider the establishment of yearly refresher courses.

The HSA's job

Regarding workload and the ever-expanding job description of the HSA's, a policy could be introduced which describes the do's and don'ts of involving HSAs in new vertical programmes, mainly coordinated by NGO. At the national level, there should be an overview of large programmes run by NGOs that involve HSAs and potentially provide incentives to HSAs. If there are national guidelines on this, it will be easier for the district to continuously assess the extra workload of HSAs and to set priorities for the HSAs work. Efforts are made to reserve funds to recruit more HSAs especially for rural areas (recruitment itself is taking place at the district level). The HSA workforce has already expanded significantlyly with the help of the Global Fund, which contributed to decreasing the workload of HSAs by reducing the number of villages they have to serve.

Other measures

The balance between provision of preventive services versus clinical and nursing services is important to consider.Prevention activities have long term effects, which makes it politically less attractive to invest. Proof of cost-effectiveness of prevention interventions requires long term research. Preventive health and the role of HSAs should get more funding, it is disproportionately underfunded now35. Also, the human resource departments at district level should increase in capacity, and this should be initiated at the national level15. At the moment, human resources staff at district level hold inadequate qualifications36 .

District level

There are several measures that can be taken at district level to motivate HSAs. These are not only HRM related measures, but also measures that have to do with the organisation of the job of the HSA and the preventive department as a whole. Health systems are open and social systems. Therefore, to improve the - in this case - preventive services, a combination of interventions is required.

Training

HSAs should be allowed to attend regular (refresher) courses organised by NGOs. The selection of HSAs for specific courses should be explained in the district training plan.

The HSA's job

District Health Management Teams (DHMTs) must avoid giving HSAs tasks that are not within their job description. A sound plan should be made for HSA distribution to cover all villages in the district and HSA allocation for specific programmes, while making sure they have enough time for community work. The DEHO should have all information regarding all active NGOs with HSA involvement.

Social

Recognition of HSAs could be improved by introducing identification (ID) cards, establishment of a departmental committee in which HSAs from different health facilities are represented and can address issues towards management (through the DEHO), and organisation of a yearly general assembly for HSAs at district level. VHC trainings should be organized and stimulated (good VHCs can lower workload for HSAs).

Communication and supervision

The District Health Management Team (DHMT) should ensure HSAs have regular and adequate supervision and feedback on performance. If supervision is adequate, hardworking HSAs could be awarded based on set criteria. Communication could be improved through the introduction of monthly meetings per zone led by a zone supervisor, work plans and reports, and a newsletter as part of the Information, Education and Communication (IEC) department.

Other factors of concern

The DHMT should make efforts to provide HSAs and their programmes sufficient transport.Also, protective clothing and emergency kits should be considered to be supplied to HSAs. Furthermore, communities could be encouraged to build good houses for HSAs.

Conclusion

This assessment shows that much effort and support is needed to keep the HSA workforce in Malawi motivated in order to maintain and further improve job performance. Both financial and non-financial incentives are important to improve motivation of HSAs. Especially for urban-based HSAs, there is a need to carefully balance hospital or health centre based work and community work. A combination of national HRM measures (regarding salary and position, training and the job description of HSAs) and district level HRM, technical measures and measures that have to do with supervision, communication and coordination can contribute to improved HSA motivation and job performance. It is the combination of these interventions that should contribute to enhancing HSA motivation and thus job performance.

Findings of this study were presented to the Ministry of Health Human Resources Technical Working Group (HR-TWG) in July 2011 to discuss national level recommendations. There was consensus regarding the recommendations by the members of the HR-TWG and they were used to further shape policies regarding the HSA workforce.

Some of the district level recommendations have already been implemented. For example, the award system for HSAs, monthly meetings, work plans and reports, a new supervision structure, inter village competitions on hygiene and VHC trainings. This package of interventions has improved health services in Mwanza. For example, there is progress on indicators on hygiene (pit latrine coverage). However, there is no proof that these improvements are solely the result of these interventions and a second assessment on motivation, job perception and satisfaction of HSAs in Mwanza has not yet been implemented. More research is needed that focuses on the effects of HRM or other interventions to enhance HSA motivation and the performance of the preventive health department at the district level in Malawi.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the cooperation of the health workers and the managers in Mwanza district during the research, and the financial and material support of VSO Malawi and Mwanza District Hospital.

References

- 1.Hornby P, Ozcan S. Malawi Human Resources for Health Sector Strategic Plan. 2003–2013 Draft January 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmer D. Tackling Malawi's human resources crisis. Reprod Health Matters. 2006;14(27):27–39. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(06)27244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franco LM, Bennett S, Kanfer R. Health sector reform and public sector health worker motivation: a conceptual framework. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00094-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herzberg F. One more time: how do you motivate employees? Harv Bus Rev. 2003;81:87–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez J. Assessing quality, outcome and performance management. Geneva, Switserland: WHO; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muula AS, Maseko FC. Survival and retention strategies for Malawian health professionals. 2005 Nov; Equinet discussion paper number 32. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muula AS, Maseko FC. How are health professionals earning their living in Malawi? BMC Health Services Research. 2006;6:97. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mangham LJ, Hanson K. Employment preferences of public sector nurses in Malawi: results from a discrete choice experiment. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(12):1433–1441. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2008.02167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley S, McAuliffe E. Mid-level providers in emergency obstetric and newborn health care: factors affecting their performance and retention within the Malawian health system. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:14. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McAuliffe E, Bowie C, Manafa O, et al. Measuring and managing the work environment of the mid-level provider - the neglected human resource. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manafa O, McAuliffe E, Maseko F, Bowie C, MacLachlan M, Normand C. Retention of health workers in Malawi: perspectives of health workers and district management. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:65. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAuliffe E, Manafa O, Maseko F, Bowie C, White E. Understanding job satisfaction amongst mid-level cadres in Malawi: the contribution of organizational justice. Reprod Health Matters. 2009;17(33):80–90. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(09)33443-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thorsen VC, Tharp ALT, Meguid T. High rates of burnout among maternal health staff at a referral hospital in Malawi: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing. 2011;10:9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6955-10-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.VSO Malawi, Malawi and Health Equity network, author. Valuing health workers. Implementing sustainable interventions to improve health worker motivation. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department for International Development (DFID) and Management Sciences for Health, author. Evaluation of Malawi's Emergency Human Resources Programme. 2010 Jul 2; [Google Scholar]

- 16.Human Resource Development Plan of the Environmental Health section of the Ministry of Health, author. Job description HSA. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hermann K, van Damme W, Pariyo GW, et al. Community health workers for ART in sub-Saharan Africa: learning from experience - capitalizing on new opportunities. Hum Resour Health. 2009;7:31. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-7-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zachariah R, Ford N, Philips M, et al. Task shifting in HIV/AIDS: opportunities, challenges and proposed actions for sub-Saharan Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103(6):549–558. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Celletti F, Wright A, Palen J, et al. Can the deployment of community health workers for the delivery of HIV services represent an effective and sustainable response to health workforce shortages? Results from a multicountry study. AIDS. 2010;24(1):S45–S57. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000366082.68321.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadzandira JM, Chilowa WR. The role of Health Surveillance Assistants (HSAs) in the delivery of health services and immunisation Malawi. University of Malawi, Centre for Social Research; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mwanza District Assembly, author. Mwanza District Socio Economic Profile. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Statistical Office Malawi, author. Projected population for Mwanza District. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lehmann U, Friedman I, Sanders D. Review of the utilisation and effectiveness of community-based health workers in Africa. Working paper of the Joint Learning Initiative. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewin SA, Babigumira SM, Bosch-Capblanch X, et al. Health Systems Research Unit. Cape Town, South Africa: Medical Research Council of South Africa; 2006. Lay health workers in primary and community health care: A systematic review of trials. [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization, author. Evidence and Information for Policy. Geneva: Department of Human Resources for Health; 2007. Jan, Policy brief. Community Health workers: What do we know about them? The state of the evidence on programmes, activities, costs and impact on health outcomes of using community health workers. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haines A, Sanders D, Lehmann U, et al. Achieving child survival goals: potential contribution of community health workers. Lancet. 2007;369(9579):2121–2131. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60325-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kane SS, Gerretsen B, Scherpbier R, Dal Poz M, Dieleman M. A realist synthesis of randomized controlled trials involving use of community health workers for delivering child health interventions in low and middle income countries. BMC Health Services Research. 2010;10:286. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-10-286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lewin S, Munabi-Babigumira S, Glenton C, et al. Lay health workers in primary and community health care for maternal and child health and the management of infectious diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004015.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mathauer I, Imhoff I. Health worker motivation in Africa: the role of non-financial incentives and human resource management tools. Hum Resour Health. 2006;4:24. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-4-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Willis-Shattuck M, Bidwell P, Thomas S, Wyness L, Blaauw D, Ditlopo P. Motivation and retention of health workers in developing countries: a systematic review. BMC Health Services Research. 2008;8:247. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhattacharyya K, Winch P, LeBan K, Tien M. Community health worker incentives and disincentives: how they affect motivation, retention, and sustainability. Arlington, Virginia: United States Agency for International Development; 2001. Published by the Basic Support for Institutionalizing Child Survival Project (BASICS II) [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dieleman M, Cuong PV, Anh LV, Martineau T. Identifying factors for job motivation of rural health workers in North Viet Nam. Hum Resour Health. 2003;1:10. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-1-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manongi RN, Marchant TC, Bygbjerg IC. Improving motivation among primary health care workers in Tanzania: a health worker perspective. Hum Resour Health. 2006;4:6. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haq Z, Iqbal Z, Rahman A. Job stress among community health workers: a multi-method study from Pakistan. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2008;2:15. doi: 10.1186/1752-4458-2-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malawi Health Equity Network, author. 2010/2011 Health Sector Budget Analysis. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Africa Health Workforce Observatory, author. Human resources for health country profile Malawi. 2009 Oct [Google Scholar]