Abstract

Objective:

To measure changes in psychometric state, neural activation, brain volume (BV), and cerebral metabolite concentrations during treatment of minimal hepatic encephalopathy.

Methods:

As proof of principle, 22 patients with well-compensated, biopsy-proven cirrhosis of differing etiology and previous minimal hepatic encephalopathy were treated with oral l-ornithine l-aspartate for 4 weeks. Baseline and 4-week clinical review, blood chemistry, and psychometric evaluation (Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score and Cognitive Drug Research Score) were performed. Whole-brain volumetric and functional MRI was conducted using a highly simplistic visuomotor task, together with proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of the basal ganglia. Treatment-related changes in regional BV and neural activation change (blood oxygenation level dependent) were assessed.

Results:

Although there was no change in clinical, biochemical state, basal ganglia magnetic resonance spectroscopy, or in regional BV, there were significant improvements in Cognitive Drug Research Score (+1.2, p = 0.003) and Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score (+1.5, p = 0.003) with treatment. This cognitive amelioration was accompanied by changes in blood oxygenation level–dependent activation in the posterior cingulate and ventral medial prefrontal cortex, 2 regions that form part of the brain's structural and metabolic core. In addition, there was evidence of greater visual cortex activation.

Conclusions:

These structurally interconnected regions all showed increased function after successful encephalopathy treatment. Because no regional change in BV was observed, this implies that mechanisms unrelated to astrocyte volume regulation were involved in the significant improvement in cognitive performance.

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE) is a neuropsychiatric complication of chronic liver disease (cirrhosis) and acute liver failure. Overt HE (OHE) ranges from mild confusion to deep coma.1 Minimal HE (MHE) (diagnosed by psychometric evaluation) is common and reduces quality of life,2 impairs daily living,3 and predicts poor outcome.4

Patients with MHE have deficits in executive inhibition, concentration, fine motor skills, and attention5 as demonstrated using the Inhibitory Control Test6 and in driving simulators.7 The Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score (PHES)8 and Cognitive Drug Research Score (CDRS)9 have been validated for quantifying deficits in MHE.

The default mode network (DMN) comprises functionally connected brain regions consistently active during rest and passive fMRI scans. Abnormal suppression occurs in epilepsy,10 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder,11 Alzheimer disease,12 and traumatic brain injury.13 Studies in patients with cirrhosis have demonstrated functional connectivity between regions including the anterior and posterior cingulate cortices, parietal lobe, and fusiform gyrus,14 and abnormal deactivation of the posterior cingulate, precuneus, and ventral medial prefrontal cortices.15 DMN activation and altered neural functioning during MHE treatment are not known.

We investigated patients with MHE to assess psychometric score, brain size, cerebral metabolites, and neural activation in MHE after treatment. For this pilot study, oral l-ornithine l-aspartate (LOLA) was used, which is thought to lower blood ammonia and brain glutamine levels through stimulating hepatic nitrogen elimination in the urea cycle.16

METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The study conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by Hammersmith Hospital ethics committee (REC no. 04/Q0406/161). All participants provided written informed consent at least 24 hours before each study.

Patients.

Inclusion criteria were biopsy-proven cirrhosis, and a history of MHE documented on psychometric evaluation. Exclusion criteria were previous hepatic decompensation manifested by OHE, cognitive deficit unrelated to HE, a history of psychoactive medication use, infection within the past 6 months, lactulose usage within the past 6 months, hyponatremia <130 mmol/L, age <18 or >65 years, abnormal high signal change on previous cerebral MRI examinations, or previous malignancy. Therefore, 22 eligible patients (15 males, 7 females) were recruited consecutively of mean (±1 SD) age 51 (±8) years, all with biopsy-proven cirrhosis and MHE. This was confirmed by PHES before entry into the study. Seven patients had alcohol-related cirrhosis, 7 had hepatitis C virus–related cirrhosis (with 3 of these patients having both as a cofactor for cirrhosis etiology), 2 had primary biliary cirrhosis, 2 had hereditary hemochromatosis, 2 had autoimmune hepatitis, 1 had hepatitis B, and 1 had cryptogenic cirrhosis. All patients abstained from alcohol for a minimum of 6 months before the study. Patients were offered treatment with oral LOLA (9 g/d) with the aim of improving the subjective symptoms of mental slowing and objective psychometric performance. In addition, 21 neurologically healthy adult controls with no history of liver disease were recruited (mean [SD] age 44 [9] years, 11 female). Control subjects only underwent the MRI component of the protocol below, and were scanned once without pharmacologic intervention.

Study design.

Within the same sitting and a 3-hour timeframe, all baseline and posttreatment visits included 1) clinical assessment, 2) serum biochemistry, 3) cognitive evaluation with computer-based CDRS and paper-based PHES, and 4) MRI examination of the brain for all 22 patients. Laboratory reference ranges were used for biochemical parameters, whereas published age- and education-adjusted normal reference ranges were used for PHES8 and Computerized Drug Research (CDR) batteries.9 Child-Pugh17 and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease18 (MELD) scores for each patient were calculated.

Cognitive assessment.

Two well-validated psychometric batteries were used on the same day as each MRI examination: the paper-based PHES8 and the CDR battery.9 The CDR subtests have been previously described9 and are related to the following cognitive processes: power of attention, continuity of attention, episodic memory, working memory, and speed of memory. The CDR battery was presented on a laptop computer with participants responding via a 2-button YES/NO response box, thus requiring no prior computer experience. A CDR battery training session was performed before the baseline assessment, and equivalent parallel forms of each test were used to prevent learning effects. The PHES test was performed in the same room. Patient data were normalized to age-matched normal controls, and z scores were produced to allow intercomparison. Subdomains and total scores were used for analysis. To detect a change in psychometric improvement over the study (+1 z score) at an α of 0.05 and power of 80%, 19 patients were required.

MRI and magnetic resonance spectroscopy protocol.

Two sets of images on all patients were acquired 4 weeks apart using a 3-tesla magnetic resonance scanner (Intera; Philips Medical Systems, Best, the Netherlands) with a 3-dimensional T1-weighted sequence and an 8-channel head coil. One hundred fifty slices were obtained with a slice thickness of 1.2 mm, repetition time (TR) of 9.64 milliseconds, echo time (TE) of 4.60 milliseconds, and flip angle of 8°.

Structural images from each MRI examination were assessed by an experienced neuroradiologist (A.D.W.) for global cortical and medial cortical atrophy to determine whether baseline atrophy was more significant in patients with potential competing pathologies (such as previous alcohol excess).

In addition to anatomical MRIs for brain volume (BV) analysis, fMRI was acquired while patients performed a simple visuomotor task. T2*-weighted gradient echo-planar images were collected with whole-brain coverage, with the following parameters: TR = 3 seconds; TE = 30 milliseconds; α = 90°, 2.2 × 2.2 axial slices, slice thickness 2.75 mm. Quadratic shim gradients were applied to correct magnetic field inhomogeneity. Patients observed a flashing checkerboard or tapped their right or left finger on their thigh. Such a simple task (finger tapping or passive viewing) minimizes the potential for performance confounds between patients or across scanning sessions. The experiment used a blocked design with visual stimulation, finger tapping, or a baseline rest condition, alternating in blocks of 24 seconds. There were 150 acquisitions, lasting 7.5 minutes.

Brain extraction, registration, and segmentation were performed using SIENA (Structural Image Evaluation, using Normalisation, of Atrophy)19 of FSL (Functional MRI of the Brain Software Library, University of Oxford, UK). Statistical analysis was performed with the Software Package for the Social Sciences (version 16.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) and Medcalc version 11.2 (Mariakerke, Belgium).

A single-voxel, point-resolved spectroscopy sequence was used to acquire proton magnetic resonance spectra of the left basal ganglia with 32 transients of the water signal followed by 128 water suppressed transients. The voxel size was 2 × 2 × 2 cm with a TR of 2,000 milliseconds and TE of 35 milliseconds. Further details of fMRI and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) data analysis are included in appendix e-1 on the Neurology® Web site at www.neurology.org.

RESULTS

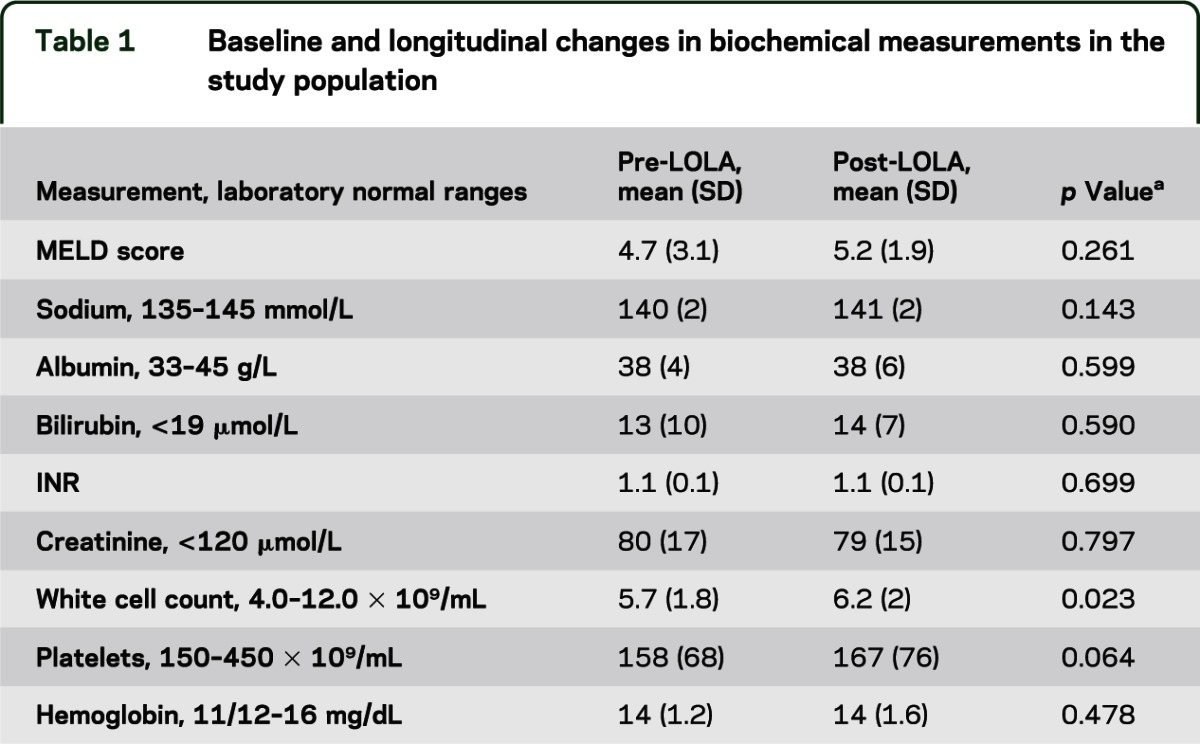

Demographics, etiology, and stage of hepatic function are presented in table 1. No patients had an episode of OHE, ascites, jaundice, infection, or gastrointestinal bleeding between baseline and the follow-up visit.

Table 1.

Baseline and longitudinal changes in biochemical measurements in the study population

Biochemistry.

Serum sodium, bilirubin, hepatic transaminases, and creatinine levels were unchanged between visits (table 1) and there was no change in Child-Pugh or MELD score. There was a small statistically but not clinically significant increase in white cell count.

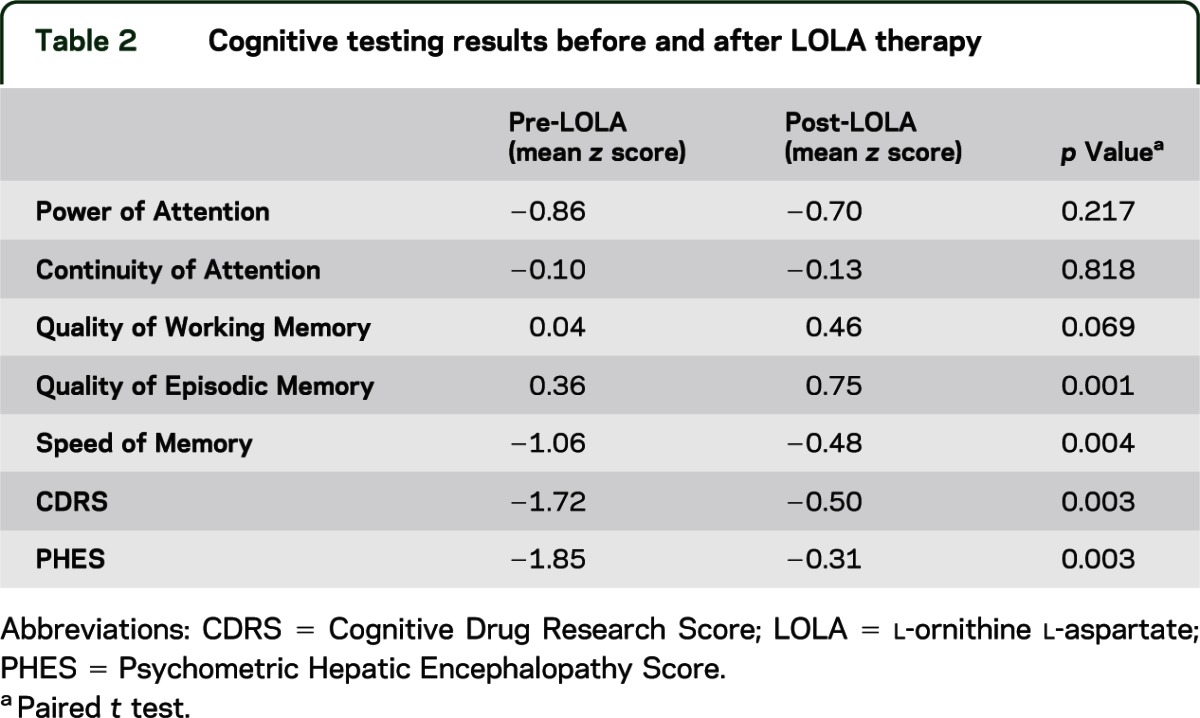

Psychometric performance.

Significant improvements in CDRS and PHES were observed (PHES mean difference [MD] +1.2, p = 0.008; CDRS MD +1.2, p = 0.003). An analysis of variance conducted on the CDR subtests revealed a significant session by subtest interaction (F4,18 = 52.8, p < 0.01 Greenhouse-Geisser corrected). Post hoc t tests subsequently revealed that the Speed of Memory (SoM) z score MD +0.6 (p = 0.005) and Quality of Episodic Memory (QoEM) z score MD +0.4 (p = 0.002, paired t testing) were the only CDR subtests that changed over session (table 2).

Table 2.

Cognitive testing results before and after LOLA therapy

Volumetric image analyses.

Longitudinal pairwise BV analysis using SIENA did not demonstrate any significant regional BV change after permutation testing, with no voxel-wise correlations with psychometric performance. There was a trend toward negative percentage BV change using SIENA, but this did not reach statistical significance (−0.18%, p = 0.120).

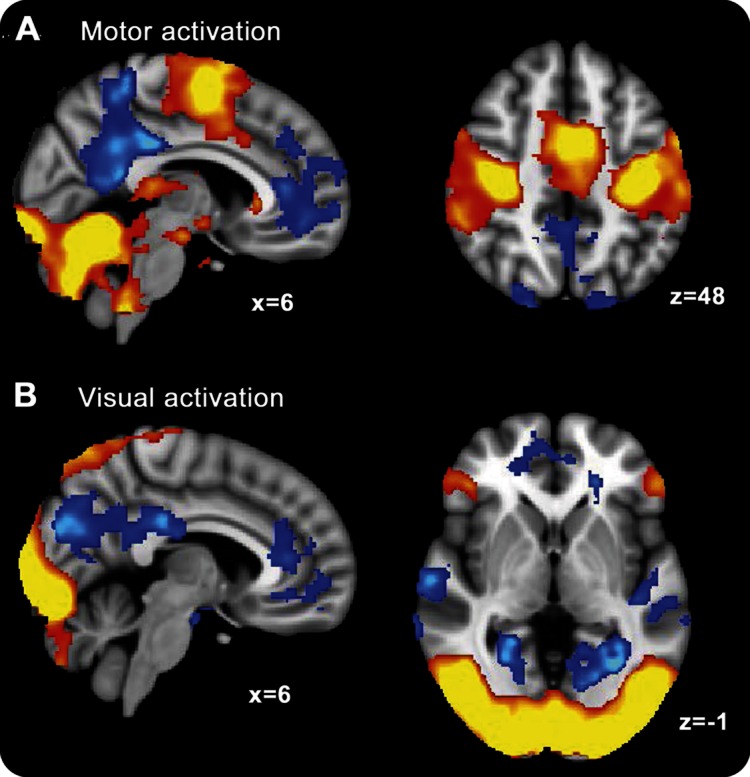

Functional magnetic resonance imaging.

Both before and after antiencephalopathy (oral LOLA) therapy, patients were scanned while finger tapping (the motor condition) or passively viewing a flashing checkerboard (the visual condition), and also at rest (the baseline condition). Figure 1 presents overall activation patterns evoked by the motor (figure 1A) and visual (figure 1B) conditions averaged across both sessions. As expected, the motor task evoked activation within frontal primary motor and supplementary motor cortices and the cerebellum, while showing a relative deactivation primarily in ventromedial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate/precuneus (parts of the DMN). The visual condition similarly activated predominantly occipital and parietal visual regions, and again deactivated medial nodes of the DMN.

Figure 1. Activation evoked by the motor and visual tasks across all patients both before and after 4 weeks of oral l-ornithine l-aspartate therapy.

Warm colors are regions that activate significantly for task, whereas blue colors are regions that activate more during the rest baseline (all results cluster-corrected for multiple comparisons, p < 0.05), (A) motor and (B) visual.

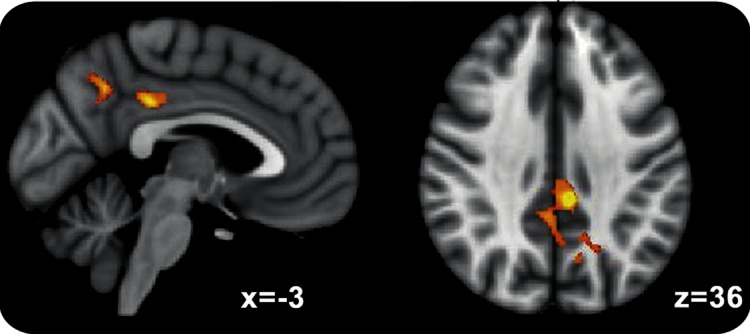

Direct comparison of scans during the motor (finger tapping) condition before and after antiencephalopathy (oral LOLA) therapy revealed that the posterior medial parietal regions (dorsal posterior cingulate and precuneus) showed greater activation after treatment (figure 2). Because these regions deactivate on task, we measured a reduction in deactivation (an evoked activation closer to zero) in the scans following antiencephalopathy (oral LOLA) treatment. However, there was no significant change in activation for the visual condition after treatment.

Figure 2. Regions that were more active in all patients.

Common areas of increased activation after 4 weeks of oral l-ornithine l-aspartate therapy (cluster-corrected for multiple comparisons, p < 0.05).

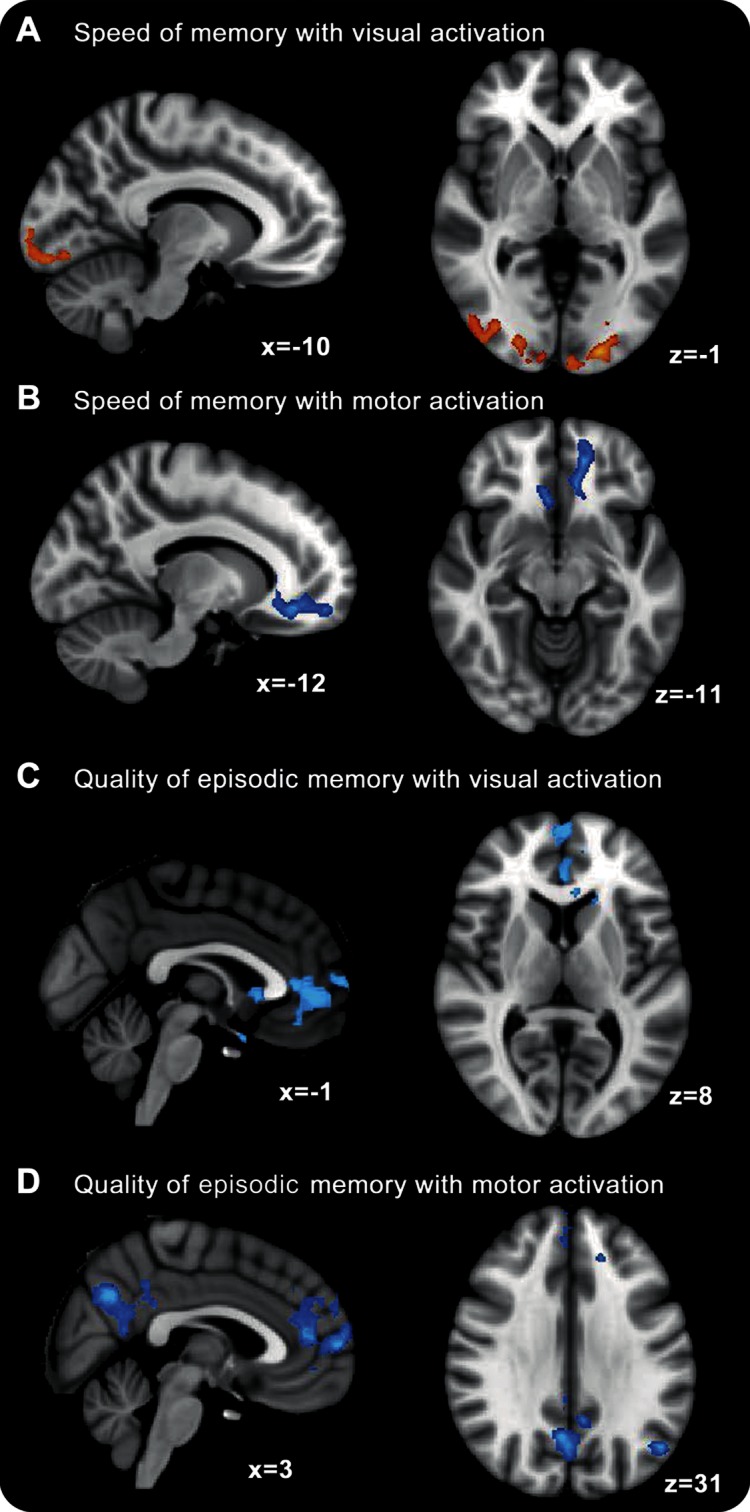

Because the effect of therapy might be confounded by the fixed order of the paradigm in which patients received the scans, the pattern of neural activation observed may reflect the fact that the posttreatment scan was the second time patients had performed the, albeit very simple, tasks. A more sensitive and interpretable analysis, from the perspective of finding treatment modulation of neural function, focuses on the individual differences in activation with individual improvements in psychometric performance. Therefore, the 2 psychometric measures from the CDR battery that significantly changed with treatment, SoM and QoEM, were compared with both visual- and motor-evoked changes in activation with treatment (figure 3). Improvement in SoM (figure 3, A and B) correlated positively with increases in visual activation in primary and association visual cortices and decreases in activation (i.e., increases in deactivation) in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, a likely part of the anterior node of the DMN. Improvement in QoEM score (figure 3, C and D) correlated with decreases in activation (increases in deactivation) within medial, lateral, and anterior parts of the DMN for both visual and motor activation. Further details on the statistical analysis for control patients are given in figure e-1 where the greater deactivation of the DMN in controls compared with patients who were CDR impaired is confirmed.

Figure 3. Relationship between change in evoked activation (motor [A/C] and visual [B/D]) and change in psychometric performance (Speed of Memory [A/B] and Quality of Episodic Memory [C/D]).

Warm colors indicate a significant positive relationship between activation (“after-before” 4 weeks of oral l-ornithine l-aspartate therapy) and behavioral performance, while cold colors indicate a negative relationship.

The pattern of neural activation found by comparing individual differences in activation and psychometric performance broadly echoes a similar pattern observed when considering cirrhosis severity. Figure e-2 shows the pattern of activation when comparing each patient's MELD score of disease severity with their pretreatment neural activation for both the visual and motor tasks. The patients were chosen because they had compensated liver disease (MELD score range 1–12), but despite this small intersubject variability, there were significant relationships between severity and neural activation within a range of medial parietal and frontal regions that fall within the DMN. As severity decreased, activation within these regions reduced, mirroring the results for change in activation with change in psychometric function.

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy.

There was no change in Glx/Cr, Cho/Cr, mI/Cr, or NAA/Cr ratios for the study population pre- and post-LOLA therapy (table e-1).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates how treatment of MHE alters neural activation. Default mode regions of the brain undergo impaired deactivation in patients with cirrhosis who have measurable deficits in attention. These responses were modulated by successful treatment with oral LOLA generating significant improvements in CDRS and PHES of psychometric performance. However, we were unable to detect a change in regional BV or cerebral metabolite concentration with LOLA therapy.

The primary pathophysiologic process in OHE has long been thought to be a glutamine-dependent astrocyte swelling, occurring in the presence of impaired nitrogen elimination. Increased glutamine is formed by amidation of glutamate as a protective mechanism, in the face of ambient hyperammonemia. Whether astrocyte swelling is driven purely osmotically, or by mitochondrial toxicity associated with increased intra-astrocytic glutamine remains debated. Although in acute liver failure the role of cerebral edema is undisputed in MHE, there is still debate over the presence of low-grade cerebral edema20 and on the role of amplified inflammatory pathways,21 neurosteroid-mediated22 GABAergic hypertonicity,23 or the relative disproportion of circulating amino acids, leading to neurotransmitter imbalance.24 MRI studies have focused on BV,25 diffusivity of brain tissue to water (using the apparent diffusion coefficient), and localization of any increase in brain water to the free or bound water pool (using magnetization transfer26). Brain glutamine levels have been measured using proton MRS,27 particularly of the basal ganglia.28

Previous studies suggested that BV can be modified by treatment, including liver transplantation in OHE, but there are no data on longitudinal volumetric changes in MHE. This study may be underpowered to detect such a small change in BV. Because shifts in cerebral osmolytes such as myo-inositol (mI) are thought to represent cellular volume autoregulation in MHE,20 the fact that we did not detect a change in either Glx/Cr or mI/Cr in this study would lend support to the idea that BV did not change. The cognitive improvement and changes in neural activation in the DMN in this study may have been brought about by other mechanisms.

There is good statistical evidence of an effect on the DMN of MHE-related attention defects, and that these were modulated by oral LOLA, distinct from modulation of astrocyte volume. Patients who experienced the greatest improvement in psychometric performance on SoM or working memory tasks showed the greatest reductions of activation within the medial DMN. These regions of the brain typically deactivate on externally focused tasks, such as watching a visual stimulus or making a movement. As such, the results suggest greater deactivation for those who benefit most from treatment. By considering disease severity, a broadly similar pattern of results are observed, suggesting that this increase in deactivation with treatment is a sign of a return to less-impaired neural function. This pattern of results is unlikely to indicate that the oral LOLA regimen that the patients received was acting selectively to improve function of medial DMN regions, such as the posterior cingulate and the ventromedial prefrontal cortices. Rather, these regions are part of the structural and functional core of the human brain,29 densely connected with many other brain regions. These DMN areas have very high metabolic rates30 and activity within them is detectable even under sedation.31 Therefore, these regions are likely to have a fundamental role in the regulation of information processing across the brain.32 This may explain why disparate neurologic and psychiatric disorders with varied etiologies and underlying mechanisms all result in disrupted DMN function. In MHE, there may be less well-ordered information processing,33 manifesting as altered activation in medial cortical hub regions, such as the DMN, observable as reduced deactivation, with accompanying significantly impaired cognitive performance on psychometric assessments. It seems logical to conclude that with successful treatment information flow becomes less impaired and both psychometric performance and DMN function (i.e, task-based deactivation) normalize.

In addition to altered DMN function, we detected improved activation of the visual cortex accompanying improved psychometric performance. Poor visual attention has been noted in patients with higher Child-Pugh scores with delayed visual reaction.34 A previous fMRI study demonstrated that visual misjudgment in patients with MHE could be attributed partly to the DMN,35 and visual evoked potentials have been shown to improve after liver transplantation.36 The data presented here confirm underlying visual inattention, which can be present in patients with cirrhosis and links this with CDRS.

This study has several limitations. A placebo group was not used in this proof of principle study so we may not have fully accounted for the potential learning effect of the psychometric tests administered 4 weeks apart. Nevertheless, although improvement in both PHES and CDRS was confirmed, the simplicity of the motor task and the passive nature of the visual task in the fMRI paradigm mitigate against substantial learning effects. An objective observation of activation modulation was seen after treatment, and this correlated robustly with CDR subtest improvements, suggesting that the improvement in cognitive function can be attributed to both a treatment effect and the DMN activation patterns detected on fMRI. These observations merit confirmation in further placebo-controlled studies of LOLA and other antiencephalopathy treatments with fMRI follow-up, over a longer period, to further quantify any conclusions drawn and potential therapeutic benefit. We chose 4 weeks because this allows sufficient time for LOLA to work but with a reduced likelihood of non–HE-related complications. Studies with longer follow-up should assess whether DMN activation normalization is maintained as we expect and whether it is protective against HE recurrence.

Second, we did not measure arterial ammonia during this study because we wished to assess the effects of simple interventions on brain function, using fMRI as the focus of investigation. Blood ammonia measurements may have provided some useful mechanistic information on LOLA action, but previous studies have demonstrated the relative futility of a random ammonia level for diagnosis in patients with MHE. Experimentally induced hyperammonemia may be a more useful construct for future study.

This study poses a series of questions. Because there was no detectable reduction in BV (anticipated by previous volumetric fMRI studies using lactulose25) and no supportive change in MRS-measurable cerebral osmolytes, could the deactivation changes in the DMN that we observed in patients treated with LOLA be attributable to improved nitrogen elimination or to other mechanisms?

The posterior cingulate cortex and precuneus are areas of high metabolic activity at the watershed of 2 cerebral arterial systems, which may render the DMN metabolically vulnerable.37 In a fluorodeoxyglucose-PET study38 comparing patients with cirrhosis and controls, glucose utilization in the anterior cingulate cortex, frontal and parieto-occipital regions, and precuneus was decreased in patients with cirrhosis with higher blood ammonia levels. There are, however, mechanisms related to GABAergic tone mediated by neurosteroids and/or proinflammatory processes that were not fully explored and could help explain the DMN deactivation abnormality that seems to accompany the attention deficit in MHE. Concurrent PET studies in patients treated with LOLA and/or with other antiencephalopathy treatments using 11C-PK11195, a ligand at peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptors or 11C flumazenil as a ligand at the GABA-benzodiazepine receptor complex, may be helpful.39 This should now be a focus for further work.

Supplementary Material

GLOSSARY

- BV

brain volume

- CDR

Cognitive Drug Research

- CDRS

Cognitive Drug Research Score

- Cho

choline-containing compounds

- Cr

creatine

- DMN

default mode network

- Glx

glutamine/glutamate

- HE

hepatic encephalopathy

- LOLA

l-ornithine l-aspartate

- MD

mean difference

- MELD

model for end-stage liver disease

- MHE

minimal hepatic encephalopathy

- mI

myo-inositol

- MRS

magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- NAA

N-acetylaspartate

- OHE

overt hepatic encephalopathy

- PHES

Psychometric Hepatic Encephalopathy Score

- QoEM

Quality of Episodic Memory

- SIENA

Structural Image Evaluation, using Normalisation, of Atrophy

- SoM

Speed of Memory

- TE

echo time

- TR

repetition time

Footnotes

Supplemental data at www.neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. M.J.W.M. analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. Dr. R.L. analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. Dr. V.P.B.G. designed the study, recruited patients, acquired data, and assisted in manuscript revision. Ms. J.A.F. acquired the imaging data. Dr. N.S.D. assisted in data analysis and manuscript revision. Ms. M.M.E.C. recruited patients and assisted in psychometric evaluation. Dr. H.P. analyzed data. Dr. B.K.S. designed psychometric examinations and analyzed data. Prof. K.W. designed psychometric examinations and analyzed data. Dr. M.A.D. designed the imaging protocols. Dr. A.D.W. analyzed imaging data. Prof. H.C.T. assisted in study design. Prof. S.D.T.-R. supervised and designed the study, recruited patients, and wrote the manuscript. Prof. S.D.T.-R. is the guarantor.

STUDY FUNDING

All authors acknowledge the infrastructure support of the National Institute for Health Research Biomedical Research Centre at Imperial College London.

DISCLOSURE

M.J.W. McPhail is supported by the Wellcome Trust, UK. R. Leech is supported by a fellowship from the Research Councils, UK. V.P.B. Grover was supported by grants from the Royal College of Physicians of London, the University of London, and the Trustees of St. Mary's Hospital, Paddington. J.A. Fitzpatrick reports no disclosures. N.S. Dhanjal is supported by the Medical Research Council UK. M.M.E. Crossey and H. Pflugrad report no disclosures. B.K. Saxby was previously employed by Cognitive Drug Research Ltd., provider of the CDRS to the pharmaceutical industry, now owned by United Biosource Corporation. The CDR system and analysis was provided unrestricted and free of charge. K. Wesnes was previously employed by Cognitive Drug Research Ltd., provider of the CDRS to the pharmaceutical industry, now owned by United Biosource Corporation. The CDR system and analysis was provided unrestricted and free of charge. M.A. Dresner, A.D. Waldman, and H.C. Thomas report no disclosures. S.D. Taylor-Robinson holds grants from the United Kingdom Medical Research Council, which provided running costs and some infrastructure support for the study. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferenci P, Lockwood A, Mullen K, Tarter R, Weissenborn K, Blei AT. Hepatic encephalopathy—definition, nomenclature, diagnosis, and quantification: final report of the working party at the 11th World Congresses of Gastroenterology, Vienna, 1998. Hepatology 2002;35:716–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhiman RK, Chawla YK. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy: time to recognise and treat. Trop Gastroenterol 2008;29:6–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bajaj JS, Hafeezullah M, Hoffmann RG, Saeian K. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy: a vehicle for accidents and traffic violations. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1903–1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tan HH, Lee GH, Thia KT, Ng HS, Chow WC, Lui HF. Minimal hepatic encephalopathy runs a fluctuating course: results from a three-year prospective cohort follow-up study. Singapore Med J 2009;50:255–260 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amodio P, Schiff S, Del Piccolo F, Mapelli D, Gatta A, Umilta C. Attention dysfunction in cirrhotic patients: an inquiry on the role of executive control, attention orienting and focusing. Metab Brain Dis 2005;20:115–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajaj JS, Hafeezullah M, Franco J, et al. Inhibitory Control Test for the diagnosis of minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Gastroenterology 2008;135:1591–1600.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bajaj JS, Hafeezullah M, Hoffmann RG, et al. Navigation skill impairment: another dimension of the driving difficulties in minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology 2008;47:596–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weissenborn K, Ennen JC, Schomerus H, Ruckert N, Hecker H. Neuropsychological characterization of hepatic encephalopathy. J Hepatol 2001;34:768–773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mardini H, Saxby BK, Record CO. Computerized psychometric testing in minimal encephalopathy and modulation by nitrogen challenge and liver transplant. Gastroenterology 2008;135:1582–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gotman J, Grova C, Bagshaw A, Kobayashi E, Aghakhani Y, Dubeau F. Generalized epileptic discharges show thalamocortical activation and suspension of the default state of the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:15236–15240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tian L, Jiang T, Wang Y, et al. Altered resting-state functional connectivity patterns of anterior cingulate cortex in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neurosci Lett 2006;400:39–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rombouts SA, Barkhof F, Goekoop R, Stam CJ, Scheltens P. Altered resting state networks in mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer's disease: an fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 2005;26:231–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinnunen KM, Greenwood R, Powell JH, et al. White matter damage and cognitive impairment after traumatic brain injury. Brain 2011;134:449–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang LJ, Yang G, Yin J, Liu Y, Qi J. Neural mechanism of cognitive control impairment in patients with hepatic cirrhosis: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Acta Radiol 2007;48:577–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang LJ, Yang G, Yin J, Liu Y, Qi J. Abnormal default-mode network activation in cirrhotic patients: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Acta Radiol 2007;48:781–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poo JL, Gongora J, Sanchez-Avila F, et al. Efficacy of oral L-ornithine-L-aspartate in cirrhotic patients with hyperammonemic hepatic encephalopathy: results of a randomized, lactulose-controlled study. Ann Hepatol 2006;5:281–288 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg 1973;60:646–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology 2001;33:464–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage 2004;23(suppl 1):S208–S219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haussinger D. Low grade cerebral edema and the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis. Hepatology 2006;43:1187–1190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shawcross DL, Wright G, Olde Damink SW, Jalan R. Role of ammonia and inflammation in minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 2007;22:125–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahboucha S, Butterworth RF. The neurosteroid system: implication in the pathophysiology of hepatic encephalopathy. Neurochem Int 2008;52:575–587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahboucha S, Butterworth RF. Role of endogenous benzodiazepine ligands and their GABA-A–associated receptors in hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 2005;20:425–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Als-Nielsen B, Koretz RL, Kjaergard LL, Gluud C. Branched-chain amino acids for hepatic encephalopathy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003:CD001939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel N, White S, Dhanjal NS, Oatridge A, Taylor-Robinson SD. Changes in brain size in hepatic encephalopathy: a coregistered MRI study. Metab Brain Dis 2004;19:431–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor-Robinson SD, Oatridge A, Hajnal JV, Burroughs AK, McIntyre N, deSouza NM. MR imaging of the basal ganglia in chronic liver disease: correlation of T1-weighted and magnetisation transfer contrast measurements with liver dysfunction and neuropsychiatric status. Metab Brain Dis 1995;10:175–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taylor-Robinson SD, Sargentoni J, Marcus CD, Morgan MY, Bryant DJ. Regional variations in cerebral proton spectroscopy in patients with chronic hepatic encephalopathy. Metab Brain Dis 1994;9:347–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miese F, Kircheis G, Wittsack HJ, et al. 1H-MR spectroscopy, magnetization transfer, and diffusion-weighted imaging in alcoholic and nonalcoholic patients with cirrhosis with hepatic encephalopathy. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2006;27:1019–1026 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hagmann P, Cammoun L, Gigandet X, et al. Mapping the structural core of human cerebral cortex. PLoS Biol 2008;6:e159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001;98:676–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greicius MD, Kiviniemi V, Tervonen O, et al. Persistent default-mode network connectivity during light sedation. Hum Brain Mapp 2008;29:839–847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leech R, Kamourieh S, Beckmann CF, Sharp DJ. Fractionating the default mode network: distinct contributions of the ventral and dorsal posterior cingulate cortex to cognitive control. J Neurosci 2011;31:3217–3224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kelly AM, Uddin LQ, Biswal BB, Castellanos FX, Milham MP. Competition between functional brain networks mediates behavioral variability. Neuroimage 2008;39:527–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amodio P, Marchetti P, Del Piccolo F, et al. Visual attention in cirrhotic patients: a study on covert visual attention orienting. Hepatology 1998;27:1517–1523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zafiris O, Kircheis G, Rood HA, Boers F, Haussinger D, Zilles K. Neural mechanism underlying impaired visual judgement in the dysmetabolic brain: an fMRI study. Neuroimage 2004;22:541–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reeves RR, Struve FA, Rash CJ, Burke RS. P300 cognitive evoked potentials before and after liver transplantation. Metab Brain Dis 2007;22:139–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayer AR, Mannell MV, Ling J, Gasparovic C, Yeo RA. Functional connectivity in mild traumatic brain injury. Hum Brain Mapp 2011;32:1825–1835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lockwood AH, Weissenborn K, Bokemeyer M, Tietge U, Burchert W. Correlations between cerebral glucose metabolism and neuropsychological test performance in nonalcoholic cirrhotics. Metab Brain Dis 2002;17:29–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cagnin A, Taylor-Robinson SD, Forton DM, Banati RB. In vivo imaging of cerebral "peripheral benzodiazepine binding sites" in patients with hepatic encephalopathy. Gut 2006;55:547–553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.