Abstract

The present study tested a mediational model of the role of religious involvement, spirituality, and physical/emotional functioning in a sample of African American men and women with cancer. Several mediators were proposed based on theory and previous research, including sense of meaning, positive and negative affect, and positive and negative religious coping. One hundred patients were recruited through oncologist offices, key community leaders and community organizations, and interviewed by telephone. Participants completed an established measure of religious involvement, the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being Scale (FACIT-SP-12 version 4), the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), the Meaning in Life Scale, the Brief RCOPE, and the SF-12, which assesses physical and emotional functioning. Positive affect completely mediated the relationship between religious behaviors and emotional functioning. Though several other constructs showed relationships with study variables, evidence of mediation was not supported. Mediational models were not significant for the physical functioning outcome, nor were there significant main effects of religious involvement or spirituality for this outcome. Implications for cancer survivorship interventions are discussed.

Keywords: Religion, Spirituality, Cancer coping, Mechanisms, Mediation, African Americans

Introduction

African Americans have higher mortality than other US racial/ethnic groups for all cancer sites combined, and for many specific cancer sites (American Cancer Society 2009). A number of sociodemographic characteristics are associated with cancer disparities, including income, race/ethnicity, age, sex, and other factors. Some cultural factors may serve to impede cancer outcomes while others may play a protective role. Part of successful coping and survivorship involves impact of the disease on physical and emotional functioning outcomes. Religious involvement and spirituality are an integral part of culture for many African Americans (Lincoln and Mamiya 1990), and are cultural factors that play a significant role in coping with serious illness including cancer. People are living longer after completing cancer treatment, with roughly 66% of those diagnosed expected to live at least 5 years post-diagnosis (Altekruse et al. 2009), which makes the study of factors related to successful coping and survivorship a timely issue.

Religious involvement, spirituality, and cancer coping

This paper will use the term religious involvement to refer to organized worship including service attendance, prayer, theological beliefs, and belief in a higher power (Thoresen 1998). Spirituality, a related term, refers to a search for meaning and purpose in life and relationship with a higher power (Jenkins and Pargament 1995; Thoresen 1998) which can but does not necessarily involve religion.

Research suggests that Americans diagnosed with cancer often use religion to cope with the disease (Bowie et al. 2001; Gall 2000; Jenkins and Pargament 1995). In a study examining religious differences between African American and White breast cancer survivors, African American women reported relying on their religiosity as a coping mechanism more than did White women (Bourjolly 1998), and often used prayer to cope with breast cancer (Henderson and Fogel 2003). African American women with breast cancer report higher public and private religiousness than White women, even after controlling for income (Bowie et al. 2003). Among individuals with terminal cancer, those who reported more advanced stages of faith had higher quality of life than those at more simple stages of faith (Swensen et al. 1993).

The majority of a random sample of nurses report referring cancer patients to clergy and chaplains (Taylor and Amenta 1994). Those with cancer often increase frequency of prayer, church attendance, and their faith (Moschella et al. 1997). Some women in a multi-racial sample with breast cancer reported that their faith had grown while others indicated that they had questioned their faith (Levine et al. 2007). Among cancer patients, prayer is used and found to be helpful, even though it can be sometimes accompanied by religious conflicts such as unanswered prayers (Taylor et al. 1999). In a qualitative study of men with prostate cancer, themes included use of prayer to cope (Walton and Sullivan 2004). In a Southeastern sample, most expressed the belief that God works through doctors and felt that they would place spiritual concerns above speaking with a physician if they were seriously ill (Mansfield et al. 2002).

Studies suggest that religious involvement plays a role in quality of life among individuals with cancer (Mytko and Knight 1999; Laubmeier et al. 2004). Religious involvement may facilitate development of meaning of the illness, which helps one to cope (Moadel et al. 1999; Kappeli 2000; Laubmeier et al. 2004). A meaning-making process may serve as an interpretive framework for patient suffering (Kappeli 2000). A review on religious involvement and illness coping suggests that religion helps to ease stress (Siegel et al. 2001).

In studies of individuals diagnosed with cancer, spirituality has been found to be positively associated with quality of life and health outcomes (Mytko and Knight 1999; Laubmeier et al. 2004). Others have reported that spirituality can become more salient to those with cancer (Wagner 1999). Cancer patients have reported spiritual needs such as having access to spiritual resources (Moadel et al. 1999).

Several previous studies have been conducted examining the role of spirituality among African Americans with cancer. Spirituality was found to increase hope and psychological well-being among African American women with breast cancer (Gibson and Parker 2003). Another study reported that during the diagnosis phase, spirituality helped with acceptance, treatment decision-making, and the meaning-making process (Simon et al. 2007). African American men have used spirituality to cope with prostate cancer (Bowie et al. 2003).

It has been proposed that spirituality be included in quality of life models in oncology research (Brady et al. 1999). Mytko and Knight (1999) concluded that religion and spirituality play a role in quality of life among those with cancer, and that these factors need to be included in quality of life studies to understand the role of body, mind, and spirit in the cancer experience.

The present study

Generally positive associations have been identified in previous literature between religious involvement, spirituality, and outcomes (e.g., functioning, quality of life) among those with cancer, particularly among African Americans. Religious involvement and spirituality are historically central to many in the African American community and are an integral part of African American culture (Lincoln and Mamiya 1990). If the field is to gain an understanding about the specific role of religious involvement and spirituality in cancer outcomes and to test theory in the area, researchers will need to be able to determine the mechanisms of these relationships, or explain not only if religious involvement and spirituality play a role in functioning in those with cancer, but how this role is explained. Faith-based cancer support efforts could be better informed and more effective by knowing what it is about religion/spirituality that helps or hinders functioning in those with the disease.

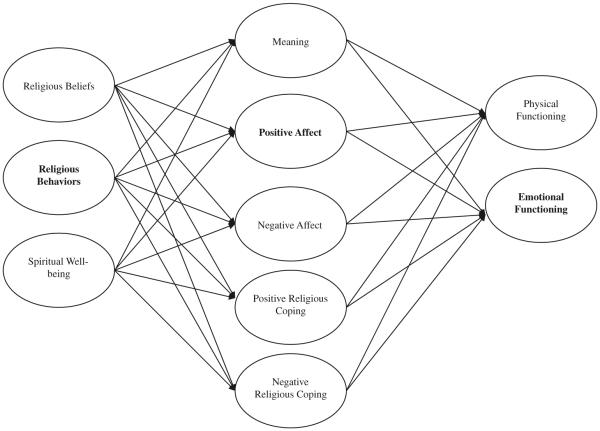

The present study reports on the testing of a theoretical model of religious involvement, spirituality and physical and emotional functioning in an African American patient sample (see Fig. 1). The model was informed by three sources. First, it was based on a qualitative foundation where African Americans with cancer completed semi-structured interviews to discuss the role of religion/spirituality in their cancer experience (Holt et al. 2009a; Schulz et al. 2008). This resulted in several important themes used to guide the current theoretical model. Each of the mediators being examined was a major theme extracted from the qualitative data analysis using inductive methods. Second, the model was informed by the aforementioned literature on the role of religious involvement and spirituality in coping with cancer. This literature suggested particularly that sense of meaning and religious coping may play an important role in religion/spirituality and coping with cancer. Third, the model was informed by previous theory and literature on the role of religious involvement and spirituality in health outcomes in general. This is particularly true for the roles of affect (Mullen 1990; Strawbridge et al. 2001; Levin and Vanderpool 1989; Oman and Thoresen 2002) and sense of meaning (Musick et al. 2000; George et al. 2000). Based on these three sources, the present mediational analysis focused on the role of positive and negative affect, sense of meaning, and religious coping (see Fig. 1). The aim was to examine whether each of these played a mediational role in the association between religious involvement, spirituality, and both physical and emotional functioning in a sample of African Americans with cancer. It was expected that each of these factors may either partially or fully mediate the relationship between religious involvement and/or spirituality, and physical and emotional functioning.

Fig. 1.

Theoretical model of the religion/spirituality-health connection among cancer patients. Note Constructs involved in mediation are indicated in bold font

Method

Participant recruitment and eligibility

Study methods and materials are also described elsewhere (Holt et al. 2009b). The Recruitment and Retention Shared Facility at the University of Alabama at Birmingham conducted recruitment and data collection activities. The University of Alabama at Birmingham Recruitment and Retention Shared Facility provides recruitment and data collection services for medical research studies, with strengths in minority recruitment and retention. The research protocol was approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board and followed a HIPAA compliant protocol. Participant eligibility was determined through use of a telephone screener to ensure that individuals were African American adults who had been diagnosed with cancer at least 6 months ago but not more than 5 years ago. Patients were not interviewed until after 6 months post-diagnosis, out of respect for the patient's initial adjustment period and to allow for the treatment period. Participants were not eligible after 5 years post-diagnosis because the five-year mark is generally considered to reflect remission, and coping may take on a different meaning after this time. Patients with any type of cancer were eligible. The exception was for nonmelanoma skin cancer, which is generally less severe and not considered to be life-threatening.

The recruitment protocol included local African American radio stations and newspapers. In addition, a number of oncologist offices, key community leaders, and other community organizations provided potential recruitment leads. No eligible individual refused participation. Nine individuals were ineligible. Of these, eight were diagnosed outside of the eligibility time frame and one was determined not to have had cancer. Another was eligible but was deemed incapable to participate in the interview due to poor health status.

Data collection

A highly experienced African American female interviewer was trained in the telephone interview protocol for this study. Individuals who came into contact with recruitment materials (e.g., fliers, advertisements, personal appeals) and were interested in participating called the interviewer who screened them for eligibility criteria. Those who were interested and eligible completed the interview at this initial contact or scheduled an appointment with the interviewer.

The interview began with a verbal informed consent script where participants were given ample opportunity to ask questions about the project. The structured interview itself began with questions about the role of support from others in the cancer experience (e.g., family, friends), moved into questions about religion/spirituality, and ended with a demographics module. Participants received a $25 gift card through the mail. Sample demographic characteristics appear in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant demographic characteristics

| (N = 100) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 50 |

| Female | 50 | |

| Age mean (sd) | 58.54 (10.69) | |

| Age median | 59 | |

| Relationship status | Single | 7 |

| Married | 48 | |

| Separated | 6 | |

| Divorced | 28 | |

| Widowed | 11 | |

| Education | Grades 1–8 | 4 |

| Grades | 5 | |

| 9–11 | ||

| Grade 12 or GED | 29 | |

| 1–3 years college | 29 | |

| 4+ years college | 32 |

Numbers may not sum to 100 due to missing data

Measures

Religious involvement & spirituality

Religious involvement

Religious involvement was measured using an established scale that has been utilized and validated with African Americans (Lukwago et al. 2001; Holt et al. 2003). In this instrument, religiosity is treated as a two-dimensional construct. Five items assess the behavioral dimension, which involves things such as church service attendance and involvement in other church activities (α = .79; .74 present sample). Four items assess the belief dimension, which involves things such as feeling the presence of God in one's life and perceiving a personal relationship with God (α = .85; .86 present sample). This two-dimensional model has been used successfully among African Americans and has demonstrated adequate test–retest reliability (r = .89) (Lukwago et al. 2001). Possible scores range from 5 to 21 for the behavioral subscale and 4–20 for the belief subscale, with higher scores indicating higher religious involvement.

Spirituality

Spirituality was assessed using the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual Well-Being scale (FACIT-SP-12 version 4) (Peterman et al. 2002). This instrument is comprised of 12 items assessed using a 5-point Likert-type scale (not at all…very much) and is widely used in medically ill populations. The reliability and validity of the instrument has been demonstrated previously (Peterman et al. 2002; Cella et al. 1993). The instrument has been illustrated to have strong internal reliability (α = .81–.88) and was positively associated with quality of life. It has also been shown to have convergent validity with measures of religion and spirituality in cancer patient samples. Internal reliability in the present sample was high (α = .87). The FACIT-SP contains two subscales (meaning and peace “I feel peaceful”; and faith “I find strength in my faith or spiritual beliefs”) as well as a total score; the total score was used in the present analysis. Possible scores range from 0 to 48, with higher scores representing higher spiritual well-being.

Proposed mediators

Positive and negative affect

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) was utilized to assess affect (Watson et al. 1988). The instrument is comprised of 20 adjectives representing positive (e.g., “interested”; “strong”) and negative (e.g., “upset”; “guilty”) affect (10 each), to which the respondent indicates the extent to which they have felt that way during the past week (1 = a little…5 = extremely). Scores are summed for a total possible of 10–50 for each subscale, with higher scores indicating higher experience of the affective state. Internal reliability was reported as high in previous samples (α = .80 and above) and there is a negative correlation between the two subscales (Watson et al. 1988). Internal reliability was also high in the present sample (α = .88 for positive affect; α = .79 for negative affect). Eight week test–retest reliability has ranged from .45 to .71 in a sample of cancer patients (Manne and Schnoll 2001). Test–retest reliability for one year was .60 and for a few weeks was .48 (Watson et al. 1988). The scale also showed factorial, convergent, and discriminant validity.

Sense of meaning

Sense of meaning was assessed using a 14-item Meaning in Life instrument developed by Krause (2004). Four dimensions are proposed to be represented in the instrument (values: “I have a system of values and beliefs that guide my daily activities”; purpose: “In terms of my life, I see a reason for my being here”; goals: “In my life, I have clear goals and aims”; and reflection on the past: “I feel good when I think about what I have done in the past”). However, it was recommended that the instrument be treated as a single composite score (Krause 2004), the approach used in the present analysis. Items were assessed in 4-point Likert-type format (1 = disagree strongly…4 = agree strongly), ranging from 14 to 56, with higher scores reflecting greater sense of meaning. Internal reliability for the total score was high (α = .87) in the present sample.

Religious coping

Religious coping was assessed with the widely used Brief RCOPE (Pargament et al. 1998). This 14-item instrument assesses positive (e.g., “Looked for a stronger connection with God”) and negative (e.g., “Wondered whether God had abandoned me”) religious coping strategies. Scores range from 7 to 28 for each subscale, with higher scores representing more use of the coping mechanism. The instrument has demonstrated adequate internal consistency (α = .87–.90, α = .78–.81, respectively, and was also high in the present sample (α = .88, .81, respectively). Factorial validity was demonstrated, supporting the two-factor solution. Items are assessed in 4-point Likert-type format (1 = not at all…4 = a great deal).

Physical and emotional functioning

Functioning was assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) SF-12 (Stewart et al. 1988). This widely used 12-item short form has been shown to have reliability and validity comparable to the longer versions (Stewart et al. 1988). The first 8 items assess physical health status and functioning (e.g., “ability to do moderate activities”; “limitations in work or activities”) and the last 4 assess emotional functioning (e.g., “accomplished less than desired as result of emotional problems”; “did work or activities less carefully than usual due to emotional problems”). Internal reliability was adequate in the present sample (α = .80 each for physical and emotional functioning). Participants rate the items using a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = none of the time; 5 = all of the time). Several items are reversed scored. Scoring follows a series of formulas using a norm-based method and calibration in which scores range from 0 to 100 with a mean of 50 and standard deviation of 10. Higher scores represent better functioning.

Analysis

Correlations were assessed to determine the bivariate relationships between all variables (see Table 2). Mediational models were tested using the method outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986; Kenny 2009). This method uses four steps in which regressions are used to assess whether either full or partial mediation occurs. In step 1, the dependent variable is “regressed onto” (entered into the regression model as the dependent variable) the independent variable. In step 2, the mediator is regressed onto the independent variable. In steps 3 and 4, the dependent variable is regressed onto both the independent variable and the mediator. The paths in steps 1 and 2 should be significant. Step 3 should demonstrate that the mediator is associated with the dependent variable. Finally, step 4 assesses the difference in the parameter estimate (independent-dependent variable relationship) as compared to step 1. The bootstrapping test of the mediation effect was used (Shrout and Bolger 2002). Bootstrapping has become the most popular method of testing mediation because it does not require the normality assumption to be met, and because it can be effectively utilized with smaller sample sizes (Preacher and Hayes 2004). If the bootstrapping test yields a significant effect for the mediator while a nonsignificant result for the independent variable, there is evidence for complete mediation. If the effect of the independent variable is attenuated, there is evidence for partial mediation. To account for potential confounders, all analyses were controlled for age and education. For the emotional functioning outcome health status was also included as a control variable. Health status was not included as a control variable in the physical health models as it was already part of the SF-12 scoring for physical functioning. This list of covariates was recommended previously for use in religion-health research (Powell et al. 2003). Covariates were entered as step one of hierarchical regression models, with predictor variables entered as step 2.

Table 2.

Correlation matrix of all study variables

| Religious beliefs | Religious behaviors | Spiritual well-being | Meaning | PANAS positive affect | PANAS negative affect | RCOPE positive | RCOPE negative | SF-12 physical | SF-12 emotional | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious beliefs | 1.00 | .69** | .57** | .47** | .27* | .09 | .43** | .004 | −.06 | .04 |

| Religious behaviors | 1.00 | .54** | .44** | .44** | −.02 | .44** | −.21* | .04 | .27** | |

| Spiritual well-being | 1.00 | .56** | .45** | −.22* | .42** | −.38** | .18 | .27** | ||

| Meaning | 1.00 | .33** | −.16 | .34** | −.18 | −.04 | .34** | |||

| PANAS positive affect | 1.00 | −.06 | .19 | −.15 | .16 | .49** | ||||

| PANAS negative affect | 1.00 | −.07 | .26* | −.04 | −.55** | |||||

| RCOPE positive | 1.00 | .07 | .03 | .12 | ||||||

| RCOPE negative | 1.00 | −.09 | −.27** | |||||||

| SF-12 physical | 1.00 | −.13 | ||||||||

| SF-12 emotional | 1.00 |

P < .05;

P < .01;

P < .001

Results

Sample characteristics

The 100 participants (half male, half female) had an average age of 58.54 years (see Table 1 for additional information). About one third had a high school education, another third had one to three years of college, and another third had four or more years of college. The median household income before taxes was in the $25,001–$35,000 bracket. Fifty five percent of the sample reported a Baptist religious affiliation and another 13% reported a Methodist affiliation. Other affiliations comprised less than 5% of the sample for each denomination. The present sample had mean levels of religiosity that were high (18.91 beliefs scale; 17.68 behaviors scale), yet comparable to those from a national probability-based sample (N = 1,006) of African Americans who did not have cancer (17.73 beliefs scale; 16.66 behaviors scale; Holt and Clark, unpublished data, 2009).

Step 1: religious involvement, spirituality and physical/ emotional functioning

The hierarchical regressions indicated that religious beliefs and behaviors were not predictive of physical functioning; however, religious behaviors were predictive of emotional functioning, P < .01 (see Table 3). Spiritual well-being was not predictive of either physical or emotional functioning (see Table 3). Contemporary approaches to mediation suggest that step 1 does not need to be present for mediation to exist, and that requiring step 1 may reduce the power to detect mediation (MacKinnon et al. 2007). However, the physical functioning models were not supported in the later steps (step 3, data not shown), thus further mediational analyses were not conducted for this outcome variable.

Table 3.

Step 1 mediation test of the relationship between religious involvement and spirituality, and physical/emotional functioning

| F | df | β | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1. IV ⇒ DV | ||||

| Physical functioning regressed onto religious beliefs | .59 | 3, 95 | −.07 | −.01 |

| Physical functioning regressed onto religious behaviors | .45 | 3, 95 | .03 | −.02 |

| Emotional functioning regressed onto religious beliefs | 2.81** | 4, 94 | .01 | .07 |

| Emotional functioning regressed onto religious behaviors | 4.19 *** | 4, 94 | .22 ** | .12 |

| Physical functioning regressed onto spiritual well-being | 1.29 | 3, 95 | .17 | .01 |

| Emotional functioning regressed onto spiritual well-being | 3.51*** | 4, 94 | .17 | .13 |

All models controlled for age and education; emotional functioning models additionally controlled for self-rated health status. Coefficients are for religious involvement or spirituality

Models for physical functioning at step three were nonsignificant

Bold font = support for step 1

P < .05;

P < .01;

P < .001

Step 2: religious involvement and spirituality, predicting the mediators

Hierarchical regressions indicated that religious beliefs and behaviors were significant predictors of meaning (Ps < .01), positive affect (Ps < .01), and positive religious coping (Ps < .01) (see Table 4). Religious beliefs and behaviors were positively associated with these mediators. Associations between religious beliefs and behaviors and negative affect and negative religious coping were not significant.

Table 4.

Step 2 mediation test of the relationship between religious involvement and spirituality, and physical/emotional functioning

| F | df | β | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 2. IV ⇒ M | ||||

| Religious involvement | ||||

| Meaning regressed onto religious beliefs | 10.60 *** | 4, 94 | .43 *** | .28 |

| Meaning regressed onto religious behaviors | 9.13 *** | 4, 94 | .40 *** | .25 |

| PANAS positive affect regressed onto religious beliefs | 3.93 *** | 4, 94 | .26 *** | .11 |

| PANAS positive affect regressed onto religious behaviors | 7.44 *** | 4, 94 | .41 *** | .21 |

| PANAS negative affect regressed onto religious beliefs | 1.86 | 4, 94 | .12 | .03 |

| PANAS negative affect regressed onto religious behaviors | 1.53 | 4, 94 | .03 | .02 |

| RCOPE positive regressed onto religious beliefs | 7.30 *** | 4, 94 | .44 *** | .21 |

| RCOPE positive regressed onto religious behaviors | 6.90 *** | 4, 94 | .44 *** | .20 |

| RCOPE negative regressed onto religious beliefs | 2.97** | 4, 94 | .04 | .08 |

| RCOPE negative regressed onto religious behaviors | 3.59*** | 4, 94 | −.15 | .10 |

| Spiritual well-being | ||||

| Meaning regressed onto spiritual well-being | 12.52 *** | 4, 94 | .52 *** | .32 |

| PANAS positive affect regressed onto spiritual well-being | 6.92 *** | 4, 94 | .43 *** | .20 |

| PANAS negative affect regressed onto spiritual well-being | 1.94 | 4, 94 | −.14 | .04 |

| RCOPE positive regressed onto spiritual well-being | 7.90 *** | 4, 92 | .50 *** | .22 |

| RCOPE negative regressed onto spiritual well-being | 5.75 *** | 4, 91 | −.33 *** | .17 |

All models controlled for age and education; emotional functioning models additionally controlled for self-rated health status. Coefficients are for religious involvement or spirituality

Models for physical functioning at step three were nonsignificant

Bold font = support for step 2

P < .05;

P < .01;

P < .001

Spiritual well-being was a significant predictor of meaning (P < .01), positive affect (P < .01), and positive and negative religious coping (Ps < .01); (see Table 4). Spiritual well-being was positively associated with the mediators, except for negative religious coping, which carried a negative association. Again, the model for negative affect was not significant.

Step 3: mediators predicting emotional functioning controlling for religious involvement and spirituality

Step three was met for one of the proposed mediators, as evidenced by significant associations with emotional functioning, while controlling for religious beliefs or behaviors. This was true for meaning (P < .01), and positive affect (Ps < .01); (see Table 5). This was not the case for positive or negative religious coping. However, only positive affect had successfully met the previous mediation steps.

Table 5.

Steps 3–4 mediation test of the relationship between religious involvement and spirituality, and physical/emotional functioning

| F | df | β | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steps 3–4. IV & M ⇒ Y | ||||

| Religious involvement | ||||

| Emotional functioning regressed onto religious beliefs and meaning*** | 4.04 *** | 5, 93 | −.13 | .13 |

| Emotional functioning regressed onto religious behaviors and meaning* | 4.09*** | 5, 93 | .14 | .14 |

| Emotional functioning regressed onto religious beliefs and PANAS positive affect*** | 7.85 *** | 5, 93 | −.11 | .26 |

| Emotional functioning regressed onto religious behaviors and PANAS positive affect *** | 7.48 *** | 5, 93 | .04 | .25 |

| Emotional functioning regressed onto religious beliefs and PANAS negative affect*** | 9.91*** | 5, 93 | .07 | .31 |

| Emotional functioning regressed onto religious behaviors and PANAS negative affect*** | 12.10*** | 5, 93 | .23 | .36 |

| Emotional functioning regressed onto religious beliefs and RCOPE positive | 2.96** | 5, 91 | −.07 | .09 |

| Emotional functioning regressed onto religious behaviors and RCOPE positive | 3.41*** | 5, 91 | .17 | .11 |

| Emotional functioning regressed onto religious beliefs and RCOPE negative* | 2.78** | 5, 90 | .01 | .09 |

| Emotional functioning regressed onto religious behaviors and RCOPE negative | 3.60*** | 5, 90 | .19* | .12 |

| Spiritual well-being | ||||

| Emotional functioning regressed onto spiritual well-being and meaning** | 3.73 *** | 5, 93 | .04 | .12 |

| Emotional functioning regressed onto spiritual well-being and PANAS positive affect*** | 7.45 *** | 5, 93 | −.02 | .25 |

| Emotional functioning regressed onto spiritual well-being and PANAS negative affect*** | 10.05*** | 5, 93 | .10 | .32 |

| Emotional functioning regressed onto spiritual well-being and RCOPE positive | 3.04*** | 5, 91 | .11 | .10 |

| Emotional functioning regressed onto spiritual well-being and RCOPE negative | 2.95** | 5, 90 | .10 | .09 |

All models controlled for age and education; emotional functioning models additionally controlled for self-rated health status. Coefficients are for religious involvement or spirituality

Models for physical functioning at step three were nonsignificant

Bold font = support for step 3. Bold font with underline = support for step 4

P < .05;

P < .01;

P < .001

Meaning (P < .05) and positive affect (P < .01) also carried significant associations with emotional functioning while controlling for spiritual well-being (see Table 3). Again, positive and negative religious coping did not. And again, the spiritual well-being models did not satisfy previous mediation steps.

Step 4: reduction in X–Y parameter estimates (Controlling for Mediator) as compared to step 1

For religious behaviors, complete mediation was evidenced for positive affect, in which the emotional functioning estimate reduced to non-significance. No other models satisfied all previous steps, and thus no others were examined at step 4. Bootstrapping indicated a significant mediation effect of positive affect (P = .01) while the independent variable became nonsignificant. The proportion result indicated that approximately 80% of the total effect was mediated by positive affect.

Discussion

The present analyses suggest that in this sample of African Americans with cancer, the positive relationship between religious involvement, specifically religious behaviors, spiritual well-being, and emotional well-being is at least in part explained by the experience of positive affective states. This study provides one of the first mediational models of religion/spirituality and cancer outcomes, particularly in a medically underserved sample. The importance of positive affect as a mediator has been discussed previously in the context of theoretical models of religion and health. It has been proposed that religion/spirituality induces a positive mental state that may act as a mediator with health outcomes (Mullen 1990). Strawbridge et al. (2001) contend that religious service attendance is related to decreased mortality in part because attendance is related to increased mental health. People high in religion/spirituality may experience positive emotions such as love or forgiveness while praying or worshipping (Kaplan et al. 1994), which may have an impact on health (Ellison and Levin 1998; Levin and Vanderpool 1989; Fredrickson 2002; Ader et al. 1991). Religious involvement may lead to positive emotions such as hope and/or gratitude, as discussed by Emmons (Farhadian and Emmons 2009; Emmons 2008). Though the present study also examined negative affect in the context of the PANAS, it was the presence of positive affect that played a mediational role. It is notable that the mediational role was expressed as experience of positive affect rather than avoidance of negative affect.

The current findings did not support a major theme that emerged from the foundational qualitative data, sense of meaning (Holt et al. 2009a; Schulz et al. 2008). The interview participants reported progressing through a journey from diagnosis through treatment, often beginning with shock and strong emotions, followed by intense soul searching in an attempt to answer the “why me” question. The qualitative findings suggested that successful resolution of that question not only leads to better emotional functioning, but that one's religious participation and spiritual well-being provide an interpretive framework for a patient to be able to make meaning out of why a thing such as cancer has happened to them. In a previous study of quality of life among individuals with leukemia and lymphoma, those with higher quality of life were those that were able to make meaning of their cancer experience through cognitive reframing (Zebrack 2000). The patients from the aforementioned qualitative interviews interpreted their cancer as being part of God's plan, allowing them to give their testimony to others, and making them stronger or better people (Holt et al. 2009a). Interestingly, sense of meaning as either a complete or partial mediator was not supported by the present data. It is possible that this may be due to the way that sense of meaning was operationalized in the current study. Perhaps a health- or cancer-specific measure of meaning would have yielded a different result, rather than a measure of general sense of meaning.

Religious coping is an area that has been explored extensively in a variety of contexts including serious illness. Pargament and colleagues describe several styles of religious coping including Self-Directing, Collaborative, and Deferring (Phillips et al. 2004; Pargament et al. 1988, 2001). Positive religious coping was associated with medical diagnoses and poorer functional and cognitive status in a hospitalized sample (Pargament et al. 1998). It is possible that those who are most ill are most likely to employ religious coping strategies. Similar findings were evidenced for negative religious coping. Negative religious coping was associated with poor physical health and quality of life, and positive religious coping was associated with better mental health in another sample of hospitalized older adults (Koenig et al. 1998). Negative religious coping, also referred to as “spiritual struggle,” was found to be associated with both lower quality of life and life satisfaction in a sample of largely White women with breast cancer (Manning-Walsh 2005).

In a sample of patients with colon cancer, a stronger relationship was found between religious coping and adaptation for women than for men (Murken et al. 2010). Among women with breast cancer, use of active surrender religious coping was associated with decreases in emotional distress and increases in emotional well-being over time (Gall et al. 2009). Use of religion while undergoing chemotherapy was associated with post-traumatic growth 2 years later (Bussell and Naus 2010). Hope was found to mediate the relationship between religiosity and styles of coping among Israeli Jewish women with breast cancer (Hasson-Ohayon et al. 2009). Though research suggests that religious coping plays a significant role in quality of life among patient samples, it does not appear to play a mediational role between religious involvement, spirituality and physical/emotional functioning, at least in this patient sample. Examination of the present bivariate relationships indicates that only negative religious coping was negatively associated with emotional functioning.

The present set of mediators did not play a significant role in physical functioning. This runs counter to previous theory and research in the religion/spirituality-health connection. However, this was a patient sample and much of the previous research and theory on religion/spirituality-health that informed the mediator selection had been conducted with healthy samples.

Generally the same group of mediators carried associations in the models with both religiosity and spirituality and emotional functioning. This finding suggests that both organized religious involvement and inner spiritual well-being may serve a similar function with regard to facilitating a sense of meaning, positive affect, and positive religious coping. However, again the mediational aspect of these models was not supported.

Strengths and limitations

Though this is one of the first studies to provide a mediational analysis of the role of religion/spirituality and health outcomes in a minority patient dataset, the data is cross sectional and therefore must be appropriately interpreted. Future longitudinal studies in this area are needed to further explore these complex relationships. In addition, though the associations between religious beliefs, spiritual well-being, and emotional functioning were statistically significant and moderate in magnitude, each accounted for only 7% of the variance in emotional functioning. This indicates that there are additional clinically significant factors that were not assessed in the current models, which also play an important role in functioning. There are sample limitations such as geographic and demographic, which limit the generalizability of the findings. Finally, due to sampling bias, individuals who were either very low in religious involvement or spirituality, or experiencing significant “spiritual struggle” (Manning-Walsh 2005) were unlikely to enroll in the study. This may have resulted in a sample that was slightly higher in overall religion/spirituality than average. However, the mean levels of religiosity in the present sample were comparable to those from a national probability-based sample of African Americans who did not have cancer (see “sample characteristics”).

Future research

The scientific study of the role of religion/spirituality in health behaviors and outcomes has only begun to examine the role of mediators and empirically test explanatory models and theories. There is much work to be done in this area, in both healthy and clinical populations. For example, the present work could be extended to populations such as Whites or Latinos to determine whether the mediators are similar or different. In addition, the mediators are likely to differ with other health issues such as sickle cell anemia or diabetes. This is particularly because some health issues have clear behavioral roots while others do not. The attributions that come along with these different conditions may make for a different role of religion/spirituality in the coping process. Finally, in our previous qualitative work (Holt et al. 2009a; Schulz et al. 2008), we observed that some patients reported increases in their religion/spirituality through the course of their cancer experience while others did not. This “religious/spiritual trajectory” is another area that may have both psychological and clinical relevance in a patient population.

Conclusions/implications

In sum, the present research revealed evidence for a mediational role of positive affect in the role of religious participation and emotional functioning in a sample of African Americans dealing with cancer. The findings have implications for survivorship interventions aimed at increasing quality of life in patient populations. For example, using worship and spiritual wellness to facilitate the experience of positive affective states may have an impact on emotional functioning. Interventions can be designed to capitalize on this mediator in the context of the faith-based experience. Such interventions are one way in which cancer survivorship and quality of life in the African American community can be strengthened.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Drs. Mark Dransfield, Andres Forero, Helen Krontiras, and Sharon Spencer, for their assistance with participant access and recruitment for this study, and Elise McLin, for her role in data collection and study coordination. This publication was supported by Grant Number (#1 U54 CA118948) from the National Cancer Institute, and was approved by the University of Alabama at Birmingham Institutional Review Board (#X051004004).

References

- Ader R, Feiten DL, Cohen N, editors. Psychoneuroimmunology. 2nd ed. Academic Press; San Diego: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Waldron W, Ruhl J, Howlader N, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Cronin K, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Stinchcomb DG, Edwards BK, editors. SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2007. National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2009. based on November 2009 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER Web site, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- American Cancer Society Cancer facts & figures for African Americans 2009–2010. Cancer epidemiological data for African Americans. 2009 cited 2009 January 23, 2009. Available from: http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/CAFF2007AAacspdf2007.pdf.

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourjolly JN. Differences in religiousness among black and white women with breast cancer. Social Work in Health Care. 1998;28:21–39. doi: 10.1300/J010v28n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowie J, Curbo B, Laveist T, Fitzgerald S, Pargament K. The relationship between religious coping style and anxiety over breast cancer in African-American women. Journal of Religion and Health. 2001;40:411–424. [Google Scholar]

- Bowie J, Sydnor KD, Granot M. Spirituality and care of prostate cancer patients: A pilot study. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2003;95:951–954. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Mo M, Cella D. A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8:417–428. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<417::aid-pon398>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussell VA, Naus MJ. A longitudinal investigation of coping and posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2010;28:61–78. doi: 10.1080/07347330903438958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Levin JS. The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education and Behavior. 1998;25:700–720. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmons RA. Gratitude: The science and spirit of thankfulness. In: Goleman D, Small G, Braden G, Lipton B, McTaggart L, editors. Measuring the immeasurable: The scientific case for spirituality. Sounds True; Boulder, CO: 2008. pp. 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Farhadian C, Emmons RA. The psychology of forgiveness in religions. In: Kalayjian A, Paloutzian RF, editors. Forgiveness and reconciliation: Psychological pathways to conflict transformation and peace building. Springer; New York: 2009. pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. How does religion benefit health and well-being? Are positive emotions active ingredients? Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13:209–213. [Google Scholar]

- Gall TL. Integrating religious resources within a general model of stress and coping: Long-term adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Religion and Health. 2000;64:65–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gall TL, Guirguis-Younger M, Charbonneau C, Florack P. The trajectory of religious coping across time in response to the diagnosis of breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18:1165–1178. doi: 10.1002/pon.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Larson DB, Koenig HG, McCullough ME. Spirituality and health: What we know, what we need to know. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2000;19:102–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson LM, Parker V. Inner resources as predictors of psychological well-being in middle-income African American breast cancer survivors. Cancer Control. 2003;10:52–59. doi: 10.1177/107327480301005s08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson-Ohayon I, Braun M, Galinsky D, Baider L. Religiosity and hope: A path for women coping with a diagnosis of breast cancer. Psychosomatics. 2009;50:525–533. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson PD, Fogel J. Support networks used by African American breast cancer support group participants. Association of Black Nursing Faculty Journal. 2003;14:95–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Caplan L, Schulz E, Blake V, Southward VL, Buckner AV. Development and validation of measures of religious involvement and the cancer experience among African Americans. Journal of Health Psychology. 2009a;14:525–535. doi: 10.1177/1359105309103572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Caplan L, Schulz E, Blake V, Southward P, Buckner A, et al. Role of religion in cancer coping among African Americans: A qualitative examination. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2009b;27:248–273. doi: 10.1080/07347330902776028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Lukwago SN, Kreuter MW. Spirituality, breast cancer beliefs and mammography utilization among urban African American women. Journal of Health Psychology. 2003;8:383–396. doi: 10.1177/13591053030083008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins RA, Pargament KI. Religion and spirituality as resources for coping with cancer. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1995;13:51–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan BH, Monroe-Blum H, Blazer DG. Religion, health, and forgiveness: Traditions and challenges. In: Levin JS, editor. Religion in aging and health: Theoretical foundations and methodological frontiers. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1994. pp. 52–77. [Google Scholar]

- Kappeli S. Between suffering and redemption. Religious motives in Jewish and Christian cancer patients' coping. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Science. 2000;14:82–88. doi: 10.1080/02839310050162307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. [Accessed 10/5/2009];Mediation. 2009 [online]. . Available: http://davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm.

- Koenig HG, Pargament KI, Nielsen J. Religious coping and health status in medically ill hospitalized older patients. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1998;186:513–521. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199809000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Stressors arising in highly valued roles, meaning in life, and the physical health status of older adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2004;59:S287–S297. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.5.s287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laubmeier KK, Zakowski SG, Bair JP. The role of spirituality in the psychological adjustment to cancer: A test of the transactional model of stress and coping. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;11:48–55. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm1101_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Vanderpool HY. Is religion therapeutically significant for hypertension? Social Science and Medicine. 1989;29:69–78. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(89)90129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine EG, Yoo G, Aviv C, Ewing C, Au A. Ethnicity and spirituality in breast cancer survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2007;1:212–225. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0024-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln CE, Mamiya LH. The black church in the African American experience. Duke University Press; Durham, NC: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lukwago SL, Kreuter MW, Bucholtz DC, Holt CL, Clark EM. Development and validation of brief scales to measure collectivism, religiosity, racial pride, and time orientation in urban African American women. Family and Community Health. 2001;24:63–71. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200110000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manne S, Schnoll R. Measuring cancer patients' psychological distress and well-being: A factor analytic assessment of the mental health inventory. Psychological Assessment. 2001;13:99–109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning-Walsh J. Spiritual struggle: Effect on quality of life and life satisfaction in women with breast cancer. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 2005;23:120–140. doi: 10.1177/0898010104272019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield CJ, Mitchell J, King DE. The doctor as God's mechanic? Beliefs in the Southeastern United States. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;54:399–409. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moadel A, Morgan C, Fatone A, Grennan J, Carter J, Laruffa G, et al. Seeking meaning and hope: Self-reported spiritual and existential needs among an ethnically-diverse cancer patient population. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8:378–385. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<378::aid-pon406>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschella VD, Pressman KR, Pressman P, Weissman DE. The problem of theodicy and religious response to cancer. Journal of Religion and Health. 1997;36:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen K. Religion and health: A review of the literature. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy. 1990;101:85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Murken S, Namini S, Gross S, Korber J. Gender specific differences in coping with colon cancer: Empirical findings with special consideration of religious coping. Rehabilitation. 2010;49:95–104. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musick MA, Traphagan JW, Koenig HG, Larson DB. Spirituality in physical health and aging. Journal of Adult Development. 2000;7:73–86. [Google Scholar]

- Mytko JJ, Knight SJ. Body, mind and spirit: Towards the integration of religiosity and spirituality in cancer quality of life research. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8:439–450. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<439::aid-pon421>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oman D, Thoresen CE. Does religion cause health? Differing interpretations and diverse meanings. Journal of Health Psychology. 2002;7:365–380. doi: 10.1177/1359105302007004326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Kennell J, Hathaway W, Grevengoed N, Newman J, Jones W. Religion and the problem-solving process: Three styles of religious coping. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1988;27:90–104. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, Perez L. Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1998;37:710–724. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Tarakeshwar N, Ellison CG, Wulff KM. Religious coping among the religious: The relationships between religious coping and well-being in a national sample of Presbyterian clergy, elders, and members. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2001;40:497–515. [Google Scholar]

- Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady M, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: The functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp) Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2002;24:49–58. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips RE, Pargament KI, Lynn QK, Crossley CD. Self-directing religious coping: A deistic God, abandoning God, or no God at all? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2004;43:409–418. [Google Scholar]

- Powell LH, Shahabi L, Thoresen CE. Religion and spirituality: Linkages to physical health. American Psychologist. 2003;58:36–52. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz E, Holt CL, Caplan L, Blake V, Southward P, Buckner A, et al. Role of spirituality in cancer coping among African Americans: A qualitative examination. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2008;2:104–115. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0050-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel K, Anderman SJ, Scrimshaw EW. Religion and coping with health-related stress. Psychology and Health. 2001;16:631–653. [Google Scholar]

- Simon CE, Crowther M, Higgerson HK. The stage-specific role of spirituality among African American Christian women throughout the breast cancer experience. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:26–34. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE., Jr. The MOS short-form general health survey. Reliability and validity in a patient population. Medical Care. 1988;26:724–735. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strawbridge WJ, Shema SJ, Cohen RD, Kaplan GA. Religious attendance increases survival by improving and maintaining good health behaviors, mental health, and social relationships. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2001;23:68–74. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2301_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swensen CH, Fuller S, Clements R. Stage of religious faith and reactions to cancer. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 1993;21:238–245. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor EJ, Amenta M. Cancer nurses' perspectives on spiritual care: Implications for pastoral care. The Journal of Pastoral Care. 1994;48:259–265. doi: 10.1177/002234099404800306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor EJ, Outlaw FH, Bernardo TR, Roy A. Spiritual conflicts associated with praying about cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1999;8:386–394. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(199909/10)8:5<386::aid-pon407>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoresen CE. Spirituality, health, and science: The coming revival? In: Roth-Roemer S, Kurpius SR, editors. The emerging role of counseling psychology in health care. W. W. Norton; New York: 1998. pp. 409–431. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GB. Cancer recovery and the spirit. Journal of Religion and Health. 1999;38:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- Walton J, Sullivan N. Men of prayer: Spirituality of men with prostate cancer: A grounded theory study. Journal of Holistic Nursing. 2004;22:133–151. doi: 10.1177/0898010104264778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zebrack B. Quality of life of long-term survivors of leukemia and lymphoma. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 2000;18:39–59. [Google Scholar]