Abstract

Human adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) secrete cytokines and growth factors that can be harnessed in a paracrine fashion for promotion of angiogenesis, cell survival, and activation of endogenous stem cells. We recently showed that hypoxia is a powerful stimulus for an angiogenic activity from ASCs in vitro and here we investigate the biological significance of this paracrine activity in an in vivo angiogenesis model. A single in vitro exposure of ASCs to severe hypoxia (<0.1% O2) significantly increased both the transcriptional and translational level of the vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) and angiogenin (ANG). The angiogenicity of the ASC-conditioned medium (ASCCM) was assessed by implanting ASCCM-treated polyvinyl alcohol sponges subcutaneously for 2 weeks in mice. The morphometric analysis of anti-CD31-immunolabeled sponge sections demonstrated an increased angiogenesis with hypoxic ASCCM treatment compared to normoxic control ASCCM treatment (percentage vascular volume; 6.0%±0.5% in the hypoxic ASCCM vs. 4.1%±0.7% in the normoxic ASCCM, P<0.05). Reduction of VEGF-A and ANG levels in the ASCCM with respective neutralizing antibodies before sponge implantation showed a significantly diminished angiogenic response (3.5%±0.5% in anti-VEGF-A treated, 3.2%±0.7% in anti-ANG treated, and 3.5%±0.6% in anti-VEGF-A/ANG treated). Further, both the normoxic and hypoxic ASCCM were able to sustain in vivo lymphangiogenesis in sponges. Collectively, the model demonstrated that the increased paracrine production of the VEGF-A and ANG in hypoxic-conditioned ASCs in vitro translated to an in vivo effect with a favorable biological significance. These results further illustrate the potential for utilization of an in vitro optimized ASCCM for in vivo angiogenesis-related applications as an effective cell-free technology.

Introduction

The regenerative potential of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) has been studied extensively in animal models of cardiovascular disease since their discovery [1,2]. With their well-known paracrine activity that promotes angiogenesis, enhances cell survival, and activates endogenous stem cells [3,4], methods that augment such paracrine activity with an aim to further the therapeutic potential of MSCs have also been investigated. For example, transplantation of MSCs overexpressing different angiogenic and cytoprotective factors, such as the stromal-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) [5], vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) [6], angiopoietin-1 [7], and angiogenin (ANG) [8] significantly improve cardiac function through increased myocardial vascular density in animal models of myocardial infarction. In addition, targeting transcription factors, such as Akt-1 [9] and GATA-4 [10] that regulate the expression of multiple paracrine factors in MSCs, have also resulted in a significant increase in the in vitro production of various angiogenic and cytoprotective factors, and cardioprotection of the infarcted heart when the cells are implanted into the myocardium.

Genetic modification of MSCs has been used to enhance their paracrine activity; however, this technique increases the risk of insertion mutation and reduces their clinical potential on safety grounds. Subsequently, nongenetic approaches that enhance the MSC paracrine activity have emerged as safer and clinically suitable alternative strategies. The idea of conditioning stem cells by subjecting them to hypoxia originated from observations in an ischemic myocardium, where a brief episode of sublethal ischemia can render the heart more resistant to subsequent lethal ischemic insults [11]. This method has since been adopted in various cell therapies in an attempt to increase the survival of cells through transplantation into a hostile ischemic environment [12]. Studies have shown that MSCs subjected to hypoxic preconditioning lead to increased expression of prosurvival and proangiogenic factors, including the hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), angiopoietin-1, VEGF, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL in vitro, and transplantation of these preconditioned MSCs improved cardiac function, most likely due to increased angiogenesis post-myocardial infarction (MI) [3,12–14].

Human adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) are a suitable stem cell population for angiogenesis-dependent applications as compared to MSCs isolated from bone marrow or dermal tissue because of their relatively more proangiogenic paracrine effect and accessibility [15]. We have previously shown that hypoxic preconditioning of ASCs enhanced their paracrine effects on endothelial cell survival and endothelial tube formation in vitro [16], but the effects of hypoxic preconditioning on angiogenic paracrine action of ASCs is yet to be examined in vivo. Therefore, the present study aimed to determine whether hypoxia-enhanced ASCs have a greater angiogenic paracrine activity by using an in vivo murine subcutaneous sponge model and to investigate the underlying mechanisms.

Materials and Methods

Collection of human tissue for isolation and primary culture of ASCs

Tissues were collected with informed consent according to the National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines and performed with approval from the St. Vincent's Health Human Research Ethics Committee. Normal human abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissues discarded during surgical procedures were collected for isolation of primary ASCs as previously described [15,17]. Briefly, minced adipose tissues were digested with 0.075% type I collagenase (Worthington Biochemical) in phosphate-buffered saline. Following centrifugation at 300g, cell pellets were resuspended in a complete medium [Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)]-low glucose containing 10% fetal calf serum and a 1% antibiotic–antimycotic solution; Invitrogen), filtered through a 100-μm nylon mesh, and centrifuged at 700g for 5 min, after which, red blood cells were lysed by resuspending the cell pellet in a 0.16 M ammonium chloride lysis buffer. The cells centrifuged at 700g for 5 min were resuspended in the complete DMEM and placed into tissue culture flasks for overnight incubation at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Media were changed every 2–3 days and passaged when cells reach 90% confluent. ASCs between passages 3 and 6 were used in these experiments.

Hypoxic conditioning

ASCs seeded at the density of 5×103 cells per cm2 were cultured in the complete DMEM until the cells were 80% confluent for all experiments unless otherwise stated. Two different methods were employed for inducing hypoxia to levels of 1% O2 and <0.1% O2 content, respectively. For the 1% O2 content, ASCs were cultured in the serum-free DMEM in the Heraeus® HERAcell® 150 tri-gas humidified incubator set at 37°C, 1% O2, and 5% CO2 for 24 h. To create a hypoxia level of <0.1%, the commercially available hypoxia system, GENbox Jar (BioMerieux), was used as previously described [16]. ASCs cultured in the serum-free DMEM were placed inside the GENbox Jar, which was hermetically sealed and placed in a humidified incubator set at a temperature of 37°C for 12, 24, or 72 h.

Collection and concentration of ASC-conditioned medium

The ASC-conditioned medium (ASCCM) was prepared by culturing ASCs in the serum-free DMEM and incubated under normoxic (20% O2) or hypoxic (<0.1% O2) conditions for 24 h. Media were then collected, centrifuged at 875g for 10 min to remove cell debris, and filtered through a 0.2-μm filter. Media were then concentrated by a factor of 50 times using Amicon® Ultra-15 centrifugal filter columns with 3-kDa molecular weight cutoff (Millipore).

Real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction

At the end of hypoxic/normoxic incubation period of 12, 24, or 72 h, total mRNA was extracted from cells using the TriReagent (Invitrogen) followed by standard RNA precipitation with chloroform (Sigma-Aldrich) and isopropanol (Sigma). cDNA was synthesized using the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems). Real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction was then conducted with the TaqMan® technology using the following primers: SDF-1 (Hs00930455_m1), VEGF-A (Hs00900054_m1), VEGF-C (Hs00153458_m1), VEGF-D (Hs01128659_m1), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; Hs00266645_m1), HGF (Hs00300159_m1), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1; Hs01547656_m1), nerve growth factor (NGF; Hs00171458_m1), ANG (Hs02379000_s1), and interleukin-8 (IL-8; Hs00174103_m1). Endogenous eukaryotic 18S ribosomal mRNA (18S, Hs99999901_s1) was amplified as the house-keeping control gene. All primers were purchased from Applied Biosystems; Assay-On-Demand primers, Australia. Reactions were carried out in duplicates in 96-well plates with the 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The real-time polymerase chain reaction was performed at 95°C for 20 s to activate the AmpliTaq Gold polymerase and continued with 50 cycles of 1 s at 95°C and 20 s at 60°C for primer dissociation and annealing/elongation, respectively. Relative fold changes were compared to the normoxia group, which were normalized to 1, and all results were expressed as relative fold changes in candidate gene expression for each treatment group.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for quantification of VEGF protein level

Secreted VEGF-A, VEGF-C, and VEGF-D proteins in the ASCCM was quantified using the Quantikine® kit (R&D Systems) according to the manufacturer's protocol. A reconstituted standard stock solution was used to prepare protein standards by serial dilution. The optical density was measured at 450 nm with λ correction at 550 nm using a VMax Kinetic Microplate Reader with the SoftMax Pro 5 Software (Molecular Devices). A standard curve was extrapolated using Prism v4.0b Software (GraphPad Software Inc.) by generating a fourth-order polynomial curve fit. The secreted protein concentration was then determined by interpolating and expressed as pg/mL.

Western blotting analysis for relative quantification of ANG protein level

The level of the ANG protein in the ASCCM was analyzed with immunoblotting. The protein concentration was quantified using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instruction. Protein samples were mixed with the Laemmli buffer and boiled for 10 min. Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were fractionated using the NuPAGE Novex 4%–12% Bis-Tris gel system (Invitrogen) by electrophoresis and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Immobilon P; Millipore) using a wet transfer method (Xcell II Blot Module; Invitrogen). The transfer of the protein was completed with a current of 250 mA for 2 h at 4°C. The membrane was blocked in 5% skim milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 for 1 h at room temperature before overnight incubation with a goat anti-human ANG antibody (1:250; R&D Systems) at 4°C followed by Alexa Fluor®680 donkey anti-goat (1:5000; Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was scanned using an Odyssey® system at 700-nm wavelength and the relative protein level was quantified with densitometry using National Institutes of Health ImageJ software.

Growth factor pull-down assay of hypoxic ASCCM

To determine the contribution of VEGF-A and ANG in ASCCM-induced angiogenesis in vivo, neutralizing antibodies against the VEGF-A (30 μg/mL; Santa Cruz) and/or ANG (10 μg/mL; R&D Systems) were incubated with the hypoxic ASCCM for 2 h at 4°C with constant agitation. The protein G Sepharose (0.25 μL protein G per μL VEGF-A antibody or 0.5 μL protein G per μL ANG antibody; Sigma-Aldrich) was then incubated with the hypoxic ASCCM containing the antibody-bound VEGF-A and ANG for another 2 h at 4°C, allowing the resin to bind to the Fc portion of the neutralizing antibodies (immunoglobulin G). At the end of the incubation period, the protein G Sepharose-conjugated neutralizing antibody-bound VEGF-A and ANG in the hypoxic ASCCM were pelleted by centrifugation at 500 g for 5 min. The supernatant was used immediately for in vivo experiments.

Murine subcutaneous sponge implantation

Experimental procedures performed were approved by the St. Vincent's Hospital Animal Ethics Committee (Melbourne, VIC, Australia) and were conducted in accordance with the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council guidelines for the care and maintenance of animals. Male C57BL/6 mice (8–10 weeks old; Animal Resources Centre, Perth, Western Australia) were maintained in-house with a 12-h dark/12-h light cycle and given water and chow ad libitum.

An established murine subcutaneous sponge model [18] was used with a slight modification to examine the in vivo angiogenic response induced by the ASCCM. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane (Baxter Healthcare Ltd.) and a midline incision (∼5 mm) made on the dorsal skin. Two subcutaneous pockets were created with blunt dissection on either side of the front limbs. A pretreated polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) sponge (10 mm in diameter and 1.5 mm thick; PVA Unlimited) was inserted into each pocket. Skin wounds were closed with sterile clips and the animals were allowed to recover. Two weeks postimplantation, the animals were euthanized with cervical dislocation and the sponges rapidly excised. Harvested sponges were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, cut into two halves through the center (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd), and paraffin embedded for routine histology and immunohistochemistry. Experimental groups include (1) the serum-free DMEM (negative control), (2) the serum-free DMEM+10 ng/mL recombinant human transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) (PeproTech) (positive control), (3) the normoxic ASCCM, (4) the hypoxic ASCCM, (5) the hypoxic ASCCM+anti-VEGF-A antibody, (6) the hypoxic ASCCM+anti-ANG antibody, and (7) the hypoxic ASCCM+anti-VEGF-A antibody+anti-ANG antibody. Investigator performing the subcutaneous implantation was blinded to the experimental groups during surgical implantation.

Histology and morphometric analysis of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis in sponges

Five-micrometer-thick transverse sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for examination of tissue morphology. To determine the percentage volume of blood and lymphatic vessels within the sponges, sections were stained immunohistochemically for CD31 (BD Pharmingen) and LYVE-1 (Abcam) to identify blood and lymphatic vessels, respectively. In brief, sections were dewaxed and rehydrated through a graded series of ethanol washes before antigen retrieval with Proteinase K (Dako) at room temperature (CD31) or a 10 mM citric acid buffer at 95°C (LYVE-1). Sections were then blocked with a serum-free protein block (Dako) and incubated with the rat anti-mouse CD31 antibody (1:100 dilution; BD Pharmingen™) or rabbit anti-mouse LYVE-1 antibody at (1:300 dilution; Abcam) overnight at 4°C. Biotinylated secondary antibodies (rabbit anti-rat IgG for CD31 and swine anti-rabbit IgG for LYVE-1) used at 1:200 dilution for 1 h at room temperature were used to detect a bound primary antibody, followed by the avidin-biotinylated-peroxidase complex (Vectastain Elite ABC Standard, PK6100; Vector) for CD31 or HRP-conjugated Streptavidin (Dako) for LYVE-1 and detection by diaminobenzidine (Thermo Scientific). The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, and mounted in DPX (VWR International). Sections with CD31 staining were analyzed by video microscopy under ×20 magnification with a computer-generated 25-point square grid (CAST system; Olympus). Fields were sampled systematically and randomly such that 50% (CD31) of the specimen was assessed. Two independent observers were blinded to the identity of the tissues. These proportional counts of tissue components were expressed as a percentage of the total points counted.

Statistical analysis

Statistics were performed using GraphPad Prism v4.0b Software. Data are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean from at least 3 independent experiments. Statistical comparisons were made using an unpaired t-test or one-way analysis of variance followed by a Bonferroni multiple comparison post hoc test where appropriate. The results were considered statistically significant when P<0.05.

Results

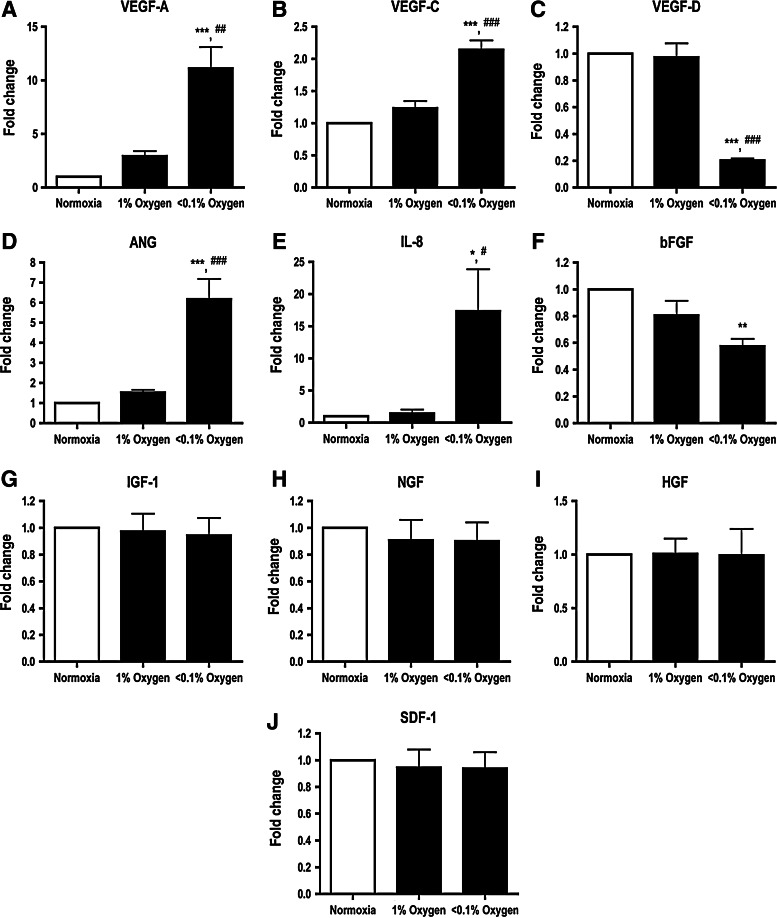

Hypoxia-regulated ASC paracrine factor profile is dependent on O2 concentration

To determine whether different degrees of hypoxia influence expression of angiogenic paracrine factors in ASCs, cells were incubated in hypoxic environments of 1% or <0.1% O2 for 24 h. mRNA expression for the VEGF-A (Fig. 1A), VEGF-C (Fig. 1B), ANG (Fig. 1D), and IL-8 (Fig. 1E) increased with <0.1% O2, but not 1% O2. In contrast, the expression levels of the VEGF-D (Fig. 1C) and bFGF (Fig. 1F) were significantly reduced in ASCs subjected to <0.1% O2. Expression levels of the IGF-1 (Fig. 1G), NGF (Fig. 1H), HGF (Fig. 1I), and SDF-1 (Fig. 1J) mRNA were unaffected by either level of hypoxia.

FIG. 1.

Degree of hypoxia differentially regulated the adipose derived stem cell (ASC) paracrine factor profile. Expression levels of the vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) (A), VEGF-C (B), angiogenin (ANG) (D), and interleukin-8 (IL-8) (E) were upregulated when ASCs were subjected to hypoxia for 24 h, while mRNA levels of the VEGF-D (C) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (F) mRNA were significantly downregulated with decreasing O2 content. mRNA expression levels of the insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) (G), nerve growth factor (NGF) (H), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) (I), and stromal-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) (J) were not affected by hypoxia. Results were expressed as relative fold change compared to the normoxia group. n=4. *, **, *** indicate P<0.05, 0.01, 0.001 versus normoxia, respectively; #, ##, ### indicate P<0.05, 0.01, 0.001 versus 1% O2 group, respectively.

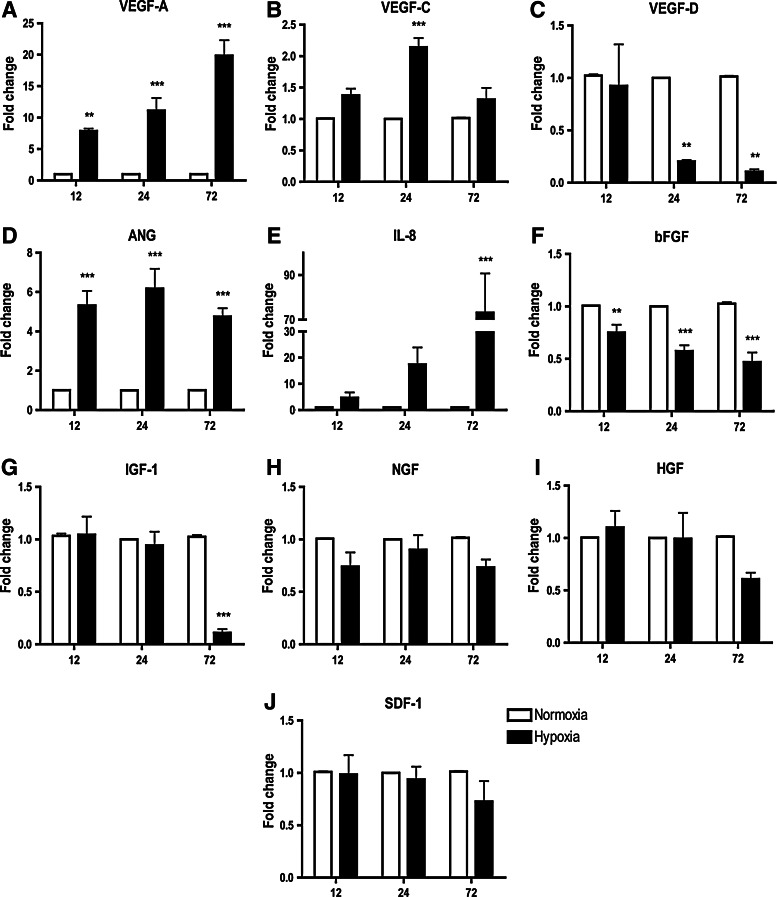

Hypoxia regulation of ASC paracrine factor profile is dependent on hypoxia duration

Hypoxia with <0.1% O2 was used in subsequent experiments as it significantly increased expression of several ASC paracrine factors. ASCs were exposed to hypoxic periods of 12, 24, or 72 h to examine whether the hypoxia duration influenced mRNA expression of candidate paracrine factors. Expression of the VEGF-A was significantly upregulated after 12 h of hypoxia (7.9±0.4-fold change) and was further increased as the hypoxia period extended to 24 (11.1±2.0-fold change) and 72 h (19.8±2.4-fold change) (Fig. 2A). A similar trend was also observed for IL-8, where the mRNA level gradually increased and was significantly upregulated at 72 h (73.1±17.6-fold change; Fig. 2E). VEGF-C expression was only significantly upregulated at 24 h (Fig. 2B), whereas the increased ANG mRNA level was apparent at 12 h (6.3±0.7-fold) and sustained for both 24 and 72 h (Fig. 2D). Hypoxia downregulated VEGF-D mRNA at 24 (0.2±0.02-fold change) and 72 h (0.1±0.02-fold change) (Fig. 2C). Expression of the bFGF was downregulated at all 3 time points (Fig. 2F). IGF-1 expression was significantly reduced only after 72 h of hypoxia (0.1±0.03-fold change; Fig. 2G). Expression of the NGF (Fig. 2H), HGF (Fig. 2I), and SDF-1 (Fig. 2J) was not influenced at any time point when exposed to hypoxia.

FIG. 2.

Effect of hypoxic period on expression of ASC paracrine factor profile. At <0.1% O2, expression of VEGF-A (A) and ANG (D) mRNA levels was significantly increased at all 3 time points, while expression of IL-8 (E) was only significantly increased at 72 h and the VEGF-C (B) was only moderately upregulated at 24 h. Conversely, VEGF-D (C), bFGF (F), and IGF-1 (G) mRNA expressions were reduced by hypoxia. Expression of the NGF (H), HGF (I), and SDF-1 (J) was not affected by hypoxia at the time points examined. Results were expressed as relative fold change compared to the normoxia group. n=4. **, *** indicate P<0.01, 0.001 versus normoxia, respectively.

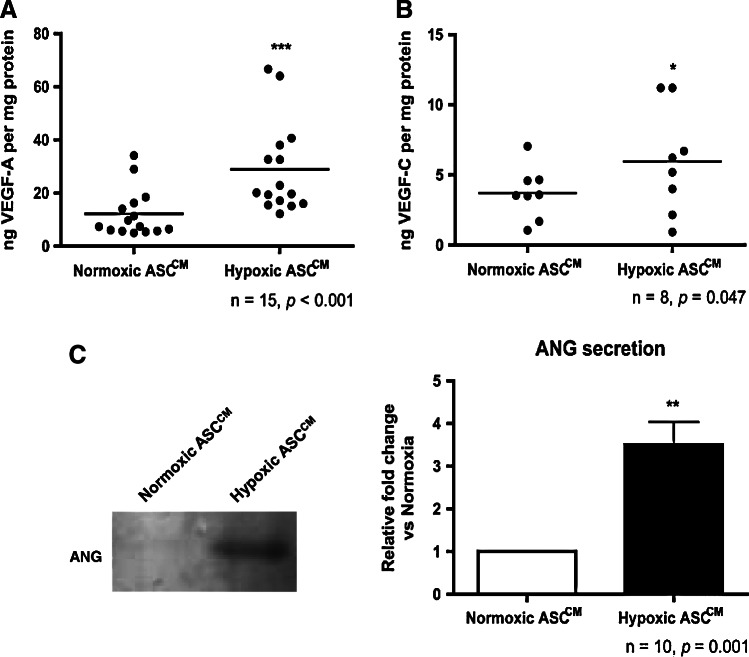

Hypoxia increases VEGF-A and ANG secretion

To confirm that increased VEGF-A, VEGF-C, and ANG mRNA levels were translated into a corresponding increase in protein secretion, the ASCCM collected from cells subjected to 24 h of normoxia or hypoxia (<0.1% O2) were analyzed by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for the VEGF and by western blotting for ANG. The VEGF-A secretion was increased nearly 3-fold in the hypoxic ASCCM as compared to the normoxic ASCCM (28.0±4.7 vs. 10.6±1.8 ng per mg protein, P<0.05; Fig. 3A). The VEGF-C protein secretion by ASCs was also increased in the hypoxic ASCCM as compared to the normoxic ASCCM (6.0±1.3 vs. 3.7±0.7 ng per mg protein, P<0.05; Fig. 3B). The VEGF-D protein level was undetectable by ELISA in all conditioned media (data not shown). A densitometry analysis revealed a 3.5-fold increase in the ANG protein in the hypoxic ASCCM as compared to the normoxic ASCCM (3.50±0.53-fold, P<0.05; Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Hypoxia increased VEGF-A, VEGF-C, and ANG secretion from ASCs. Treatment of ASCs with <0.1% O2 for 24 h led to an increase in secretion of the VEGF-A (A), VEGF-C (B), and ANG (C) compared to the protein level secreted by the normoxic ASC-conditioned medium (ASCCM). *, **, *** indicate P<0.05, 0.01, 0.001 versus the normoxic ASCCM, respectively.

Sponge histology

Explanted sponges were intact and showed no sign of degradation at 2 weeks after implantation (Supplementary Fig. S1). H&E-stained sections showed cellular infiltration was generally most prominent at the outer edges of the sponge (Supplementary Fig. S1). Compared to the negative control, TGF-β1 treatment promoted cell infiltration further into the sponge with a denser cell population and a less fibrin matrix apparent (Supplementary Fig. S2). Patent vessels with erythrocyte-filled lumens could be identified easily in the sponge postimplantation (Supplementary Fig. S2). A quantitative analysis of sections immunostained for CD31 showed increased vascularization in TGF-β1-treated sponges at 2 weeks postimplantation (5.9%±1.1% vs. 3.3%±1.5% in the negative control, P<0.05; Supplementary Fig. S2).

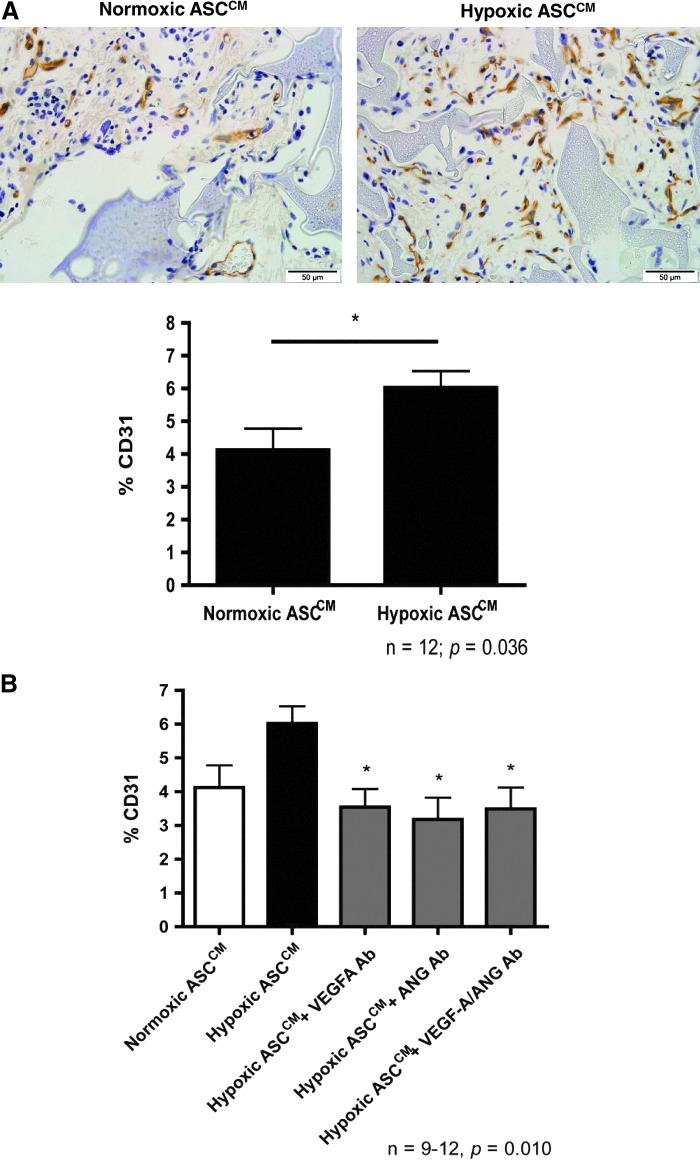

Hypoxic ASCCM promotes angiogenesis in vivo

Treatment of sponges with the hypoxic ASCCM increased CD31-positive vessels by nearly 50% when compared to normoxic ASCCM treatment at 2 weeks postimplantation (6.0%±0.5% vs. 4.1%±0.7% in the normoxic ASCCM, P<0.05; Fig. 4A). Relatively few LYVE-1 positive vessels were present (<1% of the sponge volume; Supplementary Fig. S2) at the periphery of some sponges. Only 42% (5 of 12 sponges) of the sponges treated with the normoxic ASCCM had LYVE-1-positive vessels and this level was not increased in those treated with the hypoxic ASCCM (54%; 7 of 13; P>0.05, the Fisher's exact test).

FIG. 4.

The hypoxic ASCCM promoted angiogenesis in vivo in a VEGF-A- and ANG-dependent manner. (A) The hypoxic ASCCM increased CD31-positive vessels grown into the sponges at 2 weeks postimplantation. Removal of the VEGF-A and/or ANG from the hypoxic ASCCM significantly reduced the percentage of CD31-positive vessels (B). * indicates P<0.05 versus the hypoxic ASCCM.

Enhanced angiogenic effect of hypoxia on ASCCM is dependent on VEGF-A and ANG

The hypoxic ASCCM incubated with the VEGF-A neutralizing antibody, which was subsequently bound to the protein G, resulting in a reduced level of the VEGF-A protein in the conditioned media to a similar level as in the normoxic ASCCM (9.08±2.91 ng VEGF-A per mg protein in the normoxic ASCCM vs. 5.56±4.58 ng VEGF-A per mg protein in the hypoxic ASCCM with VEGF-A neutralizing antibody treated) (Supplementary Fig. S3). Incubation with an ANG neutralizing antibody in the pull-down assay similarly reduced the level of ANG to a comparable level as in the normoxic ASCCM (0.94±0.08-fold change in the hypoxic ASCCM with the ANG neutralizing antibody treated vs. the normoxic ASCCM) (Supplementary Fig. S3). Incubation with an IgG antibody did not affect the VEGF-A and ANG levels in the hypoxic ASCCM, confirming the specificity of the antibodies used in the assay.

The percentage of anti-CD31-labeled profiles in the tissue section was reduced by removal of either the VEGF-A (3.5%±0.5%) or ANG (3.2%±0.7%) compared to the hypoxic ASCCM (6.0%±0.5%, P<0.05; Fig. 4B). However, removal of both the VEGF-A and ANG (3.5%±0.6%; Fig. 4B) did not further reduce angiogenesis as compared to either VEGF-A or ANG neutralizing antibodies alone.

Discussion

We found that hypoxic preconditioning enhanced the ASC paracrine angiogenic activity in vivo, an effect that was dependent on the VEGF-A and ANG. The murine subcutaneous sponge model employed in the present study excludes the potential cellular contribution of ASCs to angiogenesis through vascular differentiation and integration, or to changes in their paracrine factor profile when challenged with the implantation microenvironment. Instead, the observed local vessel formation in the sponges was due to paracrine factor-induced angiogenesis in vivo. Many of the published studies examining the paracrine activity of MSCs choose direct injection or transfusion of the conditioned medium, such as in the case of ischemia-induced brain damage in neonatal rats [19], porcine acute MI from surgical left circumflex coronary artery ligation [20], or the isoproterenol-induced global heart failure in rats [21]. However, methods like these largely examine the systemic delivery of the conditioned medium and effects of the paracrine activity are rapidly diluted out, especially in the case of intravenous infusion of the conditioned medium.

In the present study, ASCs subjected acutely to <0.1%, but not 1%, of O2 tension showed significantly upregulated gene expression for the VEGF-A, VEGF-C, ANG, and IL-8 and decreased gene expression for the bFGF and VEGF-D. This supports our previous data showing regulation of the HIF-1 and its downstream target VEGF-A [16], and suggests a potential involvement of O2-sensing mechanisms in acute regulation of a range of ASC paracrine factors. While tissue hypoxia may be caused by a number of conditions in vivo, such as low partial pressure of O2 in arterial blood; reduced delivery of O2 due to anemia; decreased tissue perfusion of O2; and altered microvessel geometry [22], mammalian cells have developed an intricate mechanism to detect O2 levels and initiate compensatory mechanisms when under hypoxic conditions. Several proteins and enzymes have been recognized as O2 sensors in various cell types, including potassium channels, mitochondrial complex III/IV, NADPH oxidase, and heme oxygenases [23]. Further, generation of intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) has also been considered as a part of the O2-sensing mechanisms for potassium channels and other O2-sensitive pathways [24,25]. Recent studies have reported a pivotal role for generation of ROS in ASCs through NADPH oxidase 4 when stimulated with 2% O2 tension hypoxia, leading to phosphorylation of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β and activation of ERK and Akt signaling pathways [26,27]. Hypoxia-sensitive channels have been identified in cardiomyocytes and depending on the level of O2 as well as the duration of hypoxia, some of these cardiac ion channels may be activated [25]. Further studies to define these O2 sensors in ASCs are warranted, and methods that directly activate the subsequent downstream signaling could potentially be utilized for hypoxia-independent regulation.

Production of the VEGF-A and ANG was significantly increased when the ASCs were subjected to <0.1% O2 tension. This observation was in agreement with previous findings, where hypoxia has been shown to activate the HIF-1α in various cell types that resulted in upregulation of the VEGF-A [16,28] and ANG [29,30] or both factors [31,32]. Since its discovery, the VEGF-A has been incorporated into various treatments that promote vascularization in the myocardium. While some have chosen gene transfer to promote angiogenesis post-MI [33], it has been shown that the uncontrolled expression of the VEGF can lead to vascular tumor formation, increased vessel permeability, loss of vessel stability, and vessel hyperplasia [34]. Meanwhile, treatment of post-MI cardiac failure using VEGF-A overexpressing MSCs as a carrier for persistent secretion of the angiogenic factor resulted in a reduced infarct size and an increase in angiogenesis in the myocardium [6]. ANG is an angiogenic protein with amino acid sequence resembling bovine pancreatic ribonuclease A [35], which binds to actin on the surface of endothelial cells [36] and becomes endocytosed, and then translocated to the nucleus to promote blood vessel formation [37]. Like the VEGF-A, transplantation of MSCs that overexpress ANG resulted in improvement of myocardial perfusion and cardiac function through increased vasculogenesis [8,38]. However, while the overexpression of the VEGF-A and/or ANG successfully increases the angiogenic paracrine activity of MSCs, the risks associated with use of genetically modified cells are considered to be significant limitations to clinical application. The use of hypoxia to efficiently increase the production of VEGF-A and ANG from ASCs in vitro may therefore represent an easy and clinically adaptable approach.

The increased secretion of angiogenic paracrine factors by hypoxic ASCs observed in vitro and the associated increase in angiogenesis in vivo in the implanted subcutaneous sponges loaded with the hypoxic ASCCM have confirmed the biological significance for the in vitro hypoxic regulation method. While previous studies have reported that transplantation of hypoxic preconditioned stem cells improved functional recovery of ischemic tissues in vivo [12,13,18], the improved angiogenesis in these studies was partly attributed to the enhanced survival of transplanted MSCs. Therefore, the use of the conditioned medium in the current study provides a direct evidence for the enhanced angiogenic paracrine activity of hypoxic ASCs. It remains to be seen whether the hypoxia-stimulated ASCCM provides a better wound-healing treatment than that reported for the normoxic ASCCM [39,40]. Further, we have identified the VEGF-A and ANG as major active paracrine factors that mediate the enhanced angiogenic effect of the hypoxic ASCCM. The lack of synergistic reduction in angiogenesis in vivo when both the VEGF-A and ANG were removed from the hypoxic ASCCM may suggest that the VEGF-A and ANG act on similar downstream pathways to regulate angiogenesis in vivo.

Lymphangiogenesis has been relatively less studied than angiogenesis; however, it has an important role in the physiological regulation of tissue homeostasis and metabolism. Dysregulated lymphangiogenesis may lead to edema [41], inflammatory disorders [42], and impaired wound healing [43]. Analysis of ASCs showed expression and regulation of VEGF-C and VEGF-D mRNA [15], and hypoxia increased the VEGF-C and decreased the VEGF-D in the current study. While the hypoxic ASCCM did not appear to regulate lymphangiogenesis in this subcutaneous sponge model in vivo, it is important to note that lymphangiogenesis was both limited in extent and inconsistent in sponges. Further study is warranted in alternative lymphangiogenesis models where it has been shown that local application of MSCs could promote lymphatic regeneration in a mouse tail lymphedema model [44] and in combination with the VEGF-C produced a synergistic effect on limb lymphedema [45]. It would be important to determine whether MSCs may exert this effect by inducing lymphangiogenesis either directly through differentiation into lymphatic vessel wall cells [44], or indirectly through secretion of lymphangiogenic factors.

In conclusion, hypoxic conditioning of ASCs for a period of 24 h, significantly increased secretion of angiogenic factors VEGF-A and ANG in vitro. Using a murine subcutaneous sponge implantation model, this study provides a direct evidence for paracrine angiogenic action of ASCs and demonstrated that the hypoxic ASCCM promoted a robust increase in cell infiltration and vessel formation in vivo. This enhanced angiogenesis was attributed to the increase in VEGF-A and ANG secretion by ASCs, as depletion of these angiogenic factors using specific neutralizing antibodies resulted in reduced angiogenesis in vivo. Further, the subcutaneous sponge implantation model was found to also support lymphangiogenesis in vivo. Collectively, these results support use of the in vitro-enhanced ASCCM as an alternative to cell-based therapies, where a medium conditioned by ASCs may serve as an off-the-shelf therapeutic option for acute treatment of pathological conditions that require rapid and localized vessel growth.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Priyadharshini Sivakumaran for technical assistance and grant support from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (509271, 1024817), Postgraduate Scholarship (to S.H.) and Principal Research Fellowship (to G.J.D.) and support by the JO and JR Wicking Trust. The O'Brien Institute and the Centre for Eye Research Australia acknowledge the Victorian State Government's Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development's Operational Infrastructure Support Program.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Barry FP. Murphy JM. Mesenchymal stem cells: clinical applications and biological characterization. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36:568–584. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rastegar F. Shenaq D. Huang J. Zhang W. Zhang BQ. He BC. Chen L. Zuo GW. Luo Q, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: molecular characteristics and clinical applications. World J Stem Cells. 2010;2:67–80. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v2.i4.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mirotsou M. Jayawardena TM. Schmeckpeper J. Gnecchi M. Dzau VJ. Paracrine mechanisms of stem cell reparative and regenerative actions in the heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:280–289. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams AR. Hare JM. Mesenchymal stem cells: biology, pathophysiology, translational findings, and therapeutic implications for cardiac disease. Circ Res. 2011;109:923–940. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang M. Mal N. Kiedrowski M. Chacko M. Askari AT. Popovic ZB. Koc ON. Penn MS. SDF-1 expression by mesenchymal stem cells results in trophic support of cardiac myocytes after myocardial infarction. FASEB J. 2007;21:3197–3207. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-6558com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deuse T. Peter C. Fedak PW. Doyle T. Reichenspurner H. Zimmermann WH. Eschenhagen T. Stein W. Wu JC. Robbins RC. Schrepfer S. Hepatocyte growth factor or vascular endothelial growth factor gene transfer maximizes mesenchymal stem cell-based myocardial salvage after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2009;120:S247–254. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.843680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen SL. Zhu CC. Liu YQ. Tang LJ. Yi L. Yu BJ. Wang DJ. Mesenchymal stem cells genetically modified with the angiopoietin-1 gene enhanced arteriogenesis in a porcine model of chronic myocardial ischaemia. J Int Med Res. 2009;37:68–78. doi: 10.1177/147323000903700108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang SD. Lu FL. Xu XY. Liu XH. Zhao XX. Zhao BZ. Wang L. Gong DJ. Yuan Y. Xu ZY. Transplantation of angiogenin-overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells synergistically augments cardiac function in a porcine model of chronic ischemia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:1329–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gnecchi M. He H. Liang OD. Melo LG. Morello F. Mu H. Noiseux N. Zhang L. Pratt RE. Ingwall JS. Dzau VJ. Paracrine action accounts for marked protection of ischemic heart by Akt-modified mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Med. 2005;11:367–368. doi: 10.1038/nm0405-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li H. Zuo S. He Z. Yang Y. Pasha Z. Wang Y. Xu M. Paracrine factors released by GATA-4 overexpressed mesenchymal stem cells increase angiogenesis and cell survival. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;299:H1772–H1781. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00557.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murry CE. Jennings RB. Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation. 1986;74:1124–1136. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lim SY. Dilley RJ. Dusting GJ. Advances in Regenerative Medicine. InTech; 2011. Cytoprotection and preconditioning for stem cell therapy; pp. 89–118. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu X. Yu SP. Fraser JL. Lu Z. Ogle ME. Wang JA. Wei L. Transplantation of hypoxia-preconditioned mesenchymal stem cells improves infarcted heart function via enhanced survival of implanted cells and angiogenesis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:799–808. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rehman J. Traktuev D. Li J. Merfeld-Clauss S. Temm-Grove CJ. Bovenkerk JE. Pell CL. Johnstone BH. Considine RV. March KL. Secretion of angiogenic and antiapoptotic factors by human adipose stromal cells. Circulation. 2004;109:1292–1298. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000121425.42966.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsiao ST. Asgari A. Lokmic Z. Sinclair R. Dusting GJ. Lim SY. Dilley RJ. Comparative analysis of paracrine factor expression in human adult mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, adipose, and dermal tissue. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:2189–2203. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stubbs SL. Hsiao ST. Peshavariya HM. Lim SY. Dusting GJ. Dilley RJ. Hypoxic preconditioning enhances survival of human adipose-derived stem cells and conditions endothelial cells in vitro. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:2189–2203. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuk PA. Zhu M. Ashjian P. De Ugarte DA. Huang JI. Mizuno H. Alfonso ZC. Fraser JK. Benhaim P. Hedrick MH. Human adipose tissue is a source of multipotent stem cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:4279–4295. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hague S. MacKenzie IZ. Bicknell R. Rees MC. In-vivo angiogenesis and progestogens. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:786–793. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.3.786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei X. Du Z. Zhao L. Feng D. Wei G. He Y. Tan J. Lee WH. Hampel H, et al. IFATS collection: the conditioned media of adipose stromal cells protect against hypoxia-ischemia-induced brain damage in neonatal rats. Stem Cells. 2009;27:478–488. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timmers L. Lim SK. Hoefer IE. Arslan F. Lai RC. van Oorschot AA. Goumans MJ. Strijder C. Sze SK, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium improves cardiac function following myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Res. 2011;6:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li L. Zhang S. Zhang Y. Yu B. Xu Y. Guan Z. Paracrine action mediate the antifibrotic effect of transplanted mesenchymal stem cells in a rat model of global heart failure. Mol Biol Rep. 2009;36:725–731. doi: 10.1007/s11033-008-9235-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hockel M. Vaupel P. Tumor hypoxia: definitions and current clinical, biologic, and molecular aspects. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:266–276. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.4.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Acker T. Fandrey J. Acker H. The good, the bad and the ugly in oxygen-sensing: ROS, cytochromes and prolyl-hydroxylases. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;71:195–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kemp PJ. Detecting acute changes in oxygen: will the real sensor please stand up? Exp Physiol. 2006;91:829–834. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2006.034587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hool LC. Acute hypoxia differentially regulates K(+) channels. Implications with respect to cardiac arrhythmia. Eur Biophys J. 2005;34:369–376. doi: 10.1007/s00249-005-0462-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim JH. Park SH. Park SG. Choi JS. Xia Y. Sung JH. The pivotal role of reactive oxygen species generation in the hypoxia-induced stimulation of adipose-derived stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:1753–1761. doi: 10.1089/scd.2010.0469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim JH. Song SY. Park SG. Song SU. Xia Y. Sung JH. Primary involvement of NADPH oxidase 4 in hypoxia-induced generation of reactive oxygen species in adipose-derived stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:2212–2221. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y. Cox SR. Morita T. Kourembanas S. Hypoxia regulates vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression in endothelial cells. Identification of a 5′ enhancer. Circ Res. 1995;77:638–643. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.3.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hartmann A. Kunz M. Kostlin S. Gillitzer R. Toksoy A. Brocker EB. Klein CE. Hypoxia-induced up-regulation of angiogenin in human malignant melanoma. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1578–1583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kishimoto K. Liu S. Tsuji T. Olson KA. Hu GF. Endogenous angiogenin in endothelial cells is a general requirement for cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2005;24:445–456. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pilch H. Schlenger K. Steiner E. Brockerhoff P. Knapstein P. Vaupel P. Hypoxia-stimulated expression of angiogenic growth factors in cervical cancer cells and cervical cancer-derived fibroblasts. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2001;11:137–142. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1438.2001.011002137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakamura M. Yamabe H. Osawa H. Nakamura N. Shimada M. Kumasaka R. Murakami R. Fujita T. Osanai T. Okumura K. Hypoxic conditions stimulate the production of angiogenin and vascular endothelial growth factor by human renal proximal tubular epithelial cells in culture. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1489–1495. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hao X. Mansson-Broberg A. Grinnemo KH. Siddiqui AJ. Dellgren G. Brodin LA. Sylven C. Myocardial angiogenesis after plasmid or adenoviral VEGF-A(165) gene transfer in rat myocardial infarction model. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;73:481–487. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee RJ. Springer ML. Blanco-Bose WE. Shaw R. Ursell PC. Blau HM. VEGF gene delivery to myocardium: deleterious effects of unregulated expression. Circulation. 2000;102:898–901. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.8.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saxena SK. Rybak SM. Davey RT., Jr. Youle RJ. Ackerman EJ. Angiogenin is a cytotoxic, tRNA-specific ribonuclease in the RNase A superfamily. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:21982–21986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hu GF. Strydom DJ. Fett JW. Riordan JF. Vallee BL. Actin is a binding protein for angiogenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1217–1221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.4.1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moroianu J. Riordan JF. Nuclear translocation of angiogenin in proliferating endothelial cells is essential to its angiogenic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:1677–1681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu XH. Bai CG. Xu ZY. Huang SD. Yuan Y. Gong DJ. Zhang JR. Therapeutic potential of angiogenin modified mesenchymal stem cells: angiogenin improves mesenchymal stem cells survival under hypoxia and enhances vasculogenesis in myocardial infarction. Microvasc Res. 2008;76:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim WS. Park BS. Sung JH. Yang JM. Park SB. Kwak SJ. Park JS. Wound healing effect of adipose-derived stem cells: a critical role of secretory factors on human dermal fibroblasts. J Dermatol Sci. 2007;48:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2007.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim WS. Park BS. Sung JH. The wound-healing and antioxidant effects of adipose-derived stem cells. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2009;9:879–887. doi: 10.1517/14712590903039684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Karkkainen MJ. Jussila L. Ferrell RE. Finegold DN. Alitalo K. Molecular regulation of lymphangiogenesis and targets for tissue oedema. Trends Mol Med. 2001;7:18–22. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(00)01864-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kataru RP. Jung K. Jang C. Yang H. Schwendener RA. Baik JE. Han SH. Alitalo K. Koh GY. Critical role of CD11b+ macrophages and VEGF in inflammatory lymphangiogenesis, antigen clearance, and inflammation resolution. Blood. 2009;113:5650–5659. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-176776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimamura K. Nakatani T. Ueda A. Sugama J. Okuwa M. Relationship between lymphangiogenesis and exudates during the wound-healing process of mouse skin full-thickness wound. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:598–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Conrad C. Niess H. Huss R. Huber S. von Luettichau I. Nelson PJ. Ott HC. Jauch KW. Bruns CJ. Multipotent mesenchymal stem cells acquire a lymphendothelial phenotype and enhance lymphatic regeneration in vivo. Circulation. 2009;119:281–289. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.793208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou H. Wang M. Hou C. Jin X. Wu X. Exogenous VEGF-C augments the efficacy of therapeutic lymphangiogenesis induced by allogenic bone marrow stromal cells in a rabbit model of limb secondary lymphedema. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:841–846. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyr055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.