Abstract

Fetal hydrocephalus (FH), characterized by the accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), enlarged heads, histological defects, and neurological dysfunction, is the most common neurological disorder of newborns. Although the etiology of FH remains unclear, it is known to be associated with intracranial hemorrhage. Here, we report that lysophosphatidic acid (LPA), a blood-borne lipid that activates signaling through G protein-coupled receptors, provides a molecular explanation for FH associated with hemorrhage and other conditions that increase LPA levels. A mouse model of intracranial hemorrhage in which the brains of mouse embryos were exposed to blood or LPA resulted in characteristics of FH that were dependent on the presence of the LPA1 receptor expressed by neural progenitor cells (NPCs). Administration of an LPA1 receptor antagonist blocked development of FH. These findings identify the LPA signaling pathway in the etiology of FH and suggest potential targets toward developing new therapeutics to treat FH.

Keywords: hydrocephalus, LPA, hemorrhage, G-protein coupled receptor, N-cadherin

Introduction

Fetal hydrocephalus (FH) is a life threatening condition resulting from excessive accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that occurs in 1 in 1500 newborns annually (1). FH is treated by palliative shunt placement or ventriculostomy to drain excess fluid from the brain; other neurosurgical and pharmacological interventions have proven suboptimal (2). There is some evidence for genetic contributions to rare forms of hydrocephalus but most cases are sporadic with an unclear etiology (3).

Intriguing observations have linked FH to prenatal bleeding events, such as intracranial or germinal matrix hemorrhage, which could produce pathophysiological exposure to blood derivatives like plasma and serum (1). This suggests that factors associated with blood could contribute to FH (2). Furthermore, FH has been associated with alterations in neural cell fate in the cerebral cortex, suggesting that intracranial hemorrhage and FH may share a common pathogenic process (3). A molecule found in blood and the developing cerebral cortex is the lipid lysophosphatidic acid (LPA). LPA is produced through multiple biochemical pathways (4) and has numerous biological properties that are mediated through a family of six known G protein-coupled receptors, LPA1–6 (5, 6). LPA is also a normal component of blood and blood derivatives such as plasma and serum. Human serum may have LPA concentrations exceeding 30 μM during clotting (4); this is approximately 1000-fold more than the EC50 of its receptors as measured in neural progenitor cell (NPC) assays (7). Multiple LPA receptors are expressed in the embryonic cerebral cortex (8). LPA receptor-dependent signaling influences a broad range of cellular processes that can alter the electrophysiological, cytoskeletal, morphological, anti-apoptotic, and proliferative properties of NPCs (5). NPCs, including radial glia, can divide and give rise to post-mitotic neural cells that form the stereotyped structure of the mature cerebral cortex. Additionally, radial glia generate the ciliated, ependymal cells that line the surface of the ventricles. LPA receptor-dependent effects can thus alter the overall organization of the embryonic cortex (9, 10).

To assess whether exposure of the embryonic brain to prenatal blood, serum or LPA may be implicated in FH, we developed an embryonic mouse model of FH. In this model, the brains of mouse embryos were exposed to blood components or to LPA and were analyzed pre- and postnatally for development of FH. We further investigated the role of LPA and its cognate LPA1 receptor in the induction of FH and were able to block FH development in our model using a small molecule that inhibits LPA1 receptor signaling.

Results

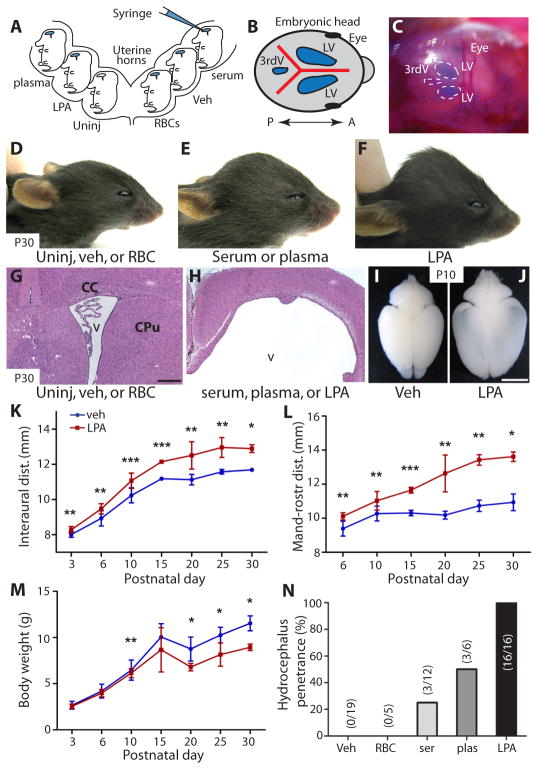

Serum or plasma exposure induces FH

Intracranial hemorrhage and blood clotting can expose the developing brain to a combination of red blood cells (RBCs), plasma, or serum. These components were isolated and delivered intraventricularly to the cerebral cortex of mouse embryos at embryonic day 13.5 (E13.5) by intracranial injection (Fig. 1A–C). Here, timed-pregnant animals underwent laparotomy in which the uterine horns were accessed, the embryos visualized by direct illumination, and the solutions delivered through the uterine wall and cranium as a single, bolus dose into the lateral ventricles. The mice were analyzed at selected fetal ages or postnatally for the development of FH. Fetal delivery of serum or plasma induced development of FH, with postnatal animals displaying characteristic dome-shaped, enlarged heads, dilated lateral ventricles (LVs), and thinning of the cortex (Fig. 1, E and H). Cohorts exposed prenatally to serum or plasma developed hydrocephalus in 25% and 50% of animals (Fig. 1N; n = 12 and n = 6, respectively), whereas uninjected animals or those exposed to vehicle or injection of RBCs did not (Fig. 1D, G, and N; n = 19). In addition, early cortical wall disruption appeared in wildtype animals after 24 hours of exposure to serum or plasma but not to RBCs (fig. S1A–F). These data indicated that hydrocephalus could be initiated by hemorrhagic components, which is consistent with epidemiological data (1) and an animal model of intracranial bleeding that reported the development of ventricular dilation and hydrocephalus (11). These data also demonstrated that neither RBCs nor an acute increase in ventricular fluid volume produced by vehicle injection were sufficient to produce sustained ventricular dilation or FH (Fig. 1, D and N). This supports the possibility that a serum or plasma factor or factors is capable of initiating hydrocephalus.

Fig. 1. Induction of hydrocephalus in mouse embryos exposed to plasma, serum, or LPA.

(A) Diagram of in utero injections. Timed-pregnant dams at E13.5 underwent laparotomy, the embryos were visualized by direct illumination, and 3 μl solutions of vehicle (HBSS), plasma, serum, RBC, or LPA were injected into individual embryonic cortices. The dams were sutured and embryos were examined after 1 day (E14.5), 5 days (E18.5), or postnatally at P4, P10, P21, and 4 weeks. (B, C) Visualization (blue) of lateral ventricles (LV) and 3rd ventricles (3rdV), indicating diffusion of injected material. Blue dye was mixed with the injection solutions so that accurate targeting of the lateral ventricles could be monitored. The presence of blue color in all ventricles indicated cerebroventricular patency. A = anterior, P = posterior. (D–F) Mice at postnatal day 30 (P30) developed macrocephalic heads after injection of plasma, serum, or LPA, but not after injection of vehicle or RBCs. (G, H) Histological examination of these injected mice (P30) showed grossly dilated ventricles (v) and thinning of the overlying cerebral cortex. (I, J) Whole-brain preparations from mice at postnatal day 10 comparing control-and LPA-injected cortex; note the increased dimensions and transparency characteristic of hydrocephalus in the LPA-injected mice (J). (K–M) Animals exposed to LPA (n = 7) (red) showed increased head dimensions and decreased body weight compared to vehicle control (n = 10) (blue). (Average ± s.d., Mann-Whiney test, see table S2 for P values, * P ≤ 0.05, ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤ 0.001). (N) Hydrocephalus penetrance was quantified for each exposure condition; numbers in parentheses represent the number of hydrocephalic animals/cohort. CC = corpus callosum, CPu = caudate and putamen. Scale bars = 400 μm (G, H) and 0.5 cm (I, J).

LPA exposure induces histological changes and FH

LPA is a bioactive factor present in both plasma and serum that can alter the organization of the embryonic cerebral cortex ex vivo (9), and its activities might contribute to the induction of FH. The effects of embryonic LPA exposure were examined in wildtype embryos at E13.5, an age when neural progenitor cells respond robustly to LPA (7, 9), and at later developmental ages. Strikingly, LPA-injected animals developed severe hydrocephalus 100% of the time (Fig. 1F, H, and N; n = 16) that was clearly visible by postnatal day 10 (P10) based on ventricular dilation and cortical thinning (Fig. 1, H and J). Hydrocephalus was not observed in vehicle-injected (n = 19) or non-injected littermates (n = 10) (Fig. 1D, G, I, and N). Hydrocephalic animals showed progressively increasing head width (interaural distance, Fig. 1K), head height (mandibular-rostral distance, Fig. 1L), and body weight loss (Fig. 1M), although there was no significant difference in the anterior-posterior dimension (fronto-occipital distance) (fig. S3A). In addition, these hydrocephalic animals displayed dome-shaped heads (Fig. 1F) and altered subcortical structures such as caudate, putamen and corpus callosum (Fig. 1H). Hydrocephalic animals survived from 2–6 weeks after birth (fig. S3B).

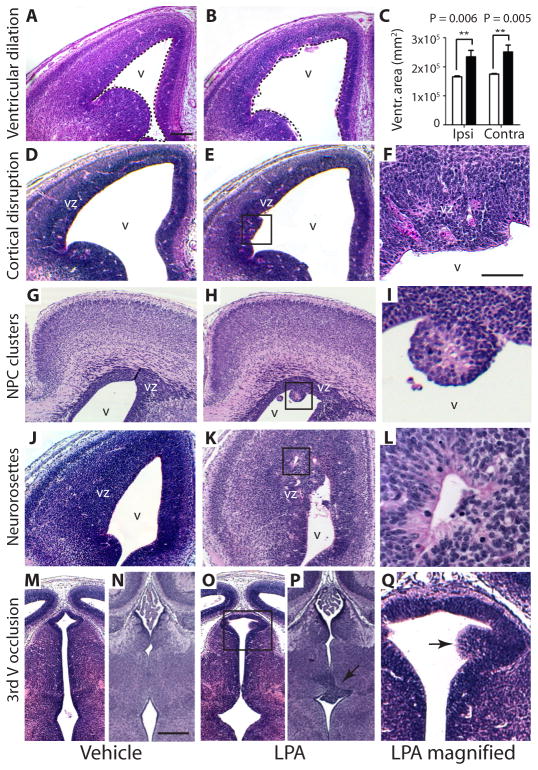

Histological alterations found in mouse models and clinical cases of human hydrocephalus (Table 1) were observed after exposure to LPA, but not vehicle control. Lateral ventricular size was bilaterally increased after LPA exposure compared to vehicle control (Fig. 2A–C and fig. S4A–L). In addition, the apical ventricular surface (comprising of NPCs at this age) was disrupted and showed protrusions into the lateral ventricles (Fig. 2D–F). In severely disrupted areas, rounded cell clusters appeared to detach from the ventricular surface (Fig. 2G–I). These clusters were immunoreactive for nestin (an NPC marker), incorporated bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU), and expressed Lpar1 detected by in situ hybridization (fig. S5A–I). Lpar1 expression is present in the ventricular zone (VZ) of the brain, confirming that the clusters were of VZ origin. Furthermore, the formation of neurorosettes – abnormal, radially-oriented cells – within the VZ was observed (Fig. 2J–L). Finally, other areas of the cerebroventricular system were also affected. The 3rd ventricle, another CSF-filled cavity located caudal and medial to the lateral ventricles, was also affected. Cells from the 3rd ventricular wall protruded into the CSF-filled ventricle, consistent with partial 3rd ventricle occlusion (Fig. 2M–Q). This abnormal localization of cells is consistent with observed heterotopia formation in FH (12). One mechanism that could contribute to these diverse histological findings is altered adhesion of NPCs to affect cell migration and positioning that could be induced by LPA signaling (13).

Table 1.

Shared histological features of hydrocephalus in mouse models and FH patients.

| Top features of fetal hydrocephalus | Clinical evidence | References* | Evidence from experimental models | References* | Serum, plasma, or LPA exposure (current study) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of intracranial hemorrhage | Strongest co-morbidity factor for FH in epidemiological studies, occurring in 30% of cases | 1, 23, 34 | To model hemorrhage in FH, neonatal rats were injected with whole and citrated blood, producing ventricular dilation and hydrocephalus | 11, 35 | Reported in this study that exposure to the blood-borne lipid LPA itself or from blood component sources initiates FH in a novel mouse model |

| Ventricular dilation | Defined as an atrial width > 3 standard deviations above mean and typically precedes frank FH in epidemiological studies. Often but not always associated with intracranial hemorrhage. | 1, 3, 25, 34 | Reported in models of blood injections; reported in genetic null mice in which proteins related to cilia, cell polarity, or cell adhesion function were removed | 11, 16–20, 24, 26–29, 35 | Embryonic mice developed cerebral ventricular dilation within 24 hours after exposure to these agents |

| Neural progenitor cell disruption | Clusters of β-III-tubulin+ neuroblasts protruding into the ventricles of neonates suffering from FH | 12, 25 | Reported in N-cadherin and hyh mutant mice. Embryonic cortical walls showed mitotic displacement whereby neural progenitor cells at the apical surface of the lateral ventricles were located misplaced basally | 14, 15, 19, 29, 45 | Exposure of embryonic mice to LPA or blood components caused mitotic displacement, as seen in N-cadherin null mutants |

| Ependymal cell loss | Incomplete loss within lateral ventricles at 16 weeks of gestation, progressive severity by 36–40 weeks with concomittant gliosis. Also reported cell loss within 4th ventricle, especially at sites of hemorrhage | 23, 25 | Reported in genetic null mice in which proteins related to cilia, cell polarity, or cell adhesion function were removed. | 16, 18, 20, 24, 29, 35 | Ependymal loss occurred by early postnatal ages, appearing as loss of S100β+ cells that line the ventricles |

| Neurorosette appearance | These aberrant, radially-shaped structures were found localized near areas of ependymal cell loss and hemorrhage | 23, 25 | Observed in cortical walls of N-cadherin null mutants, in cases of administration of N-cadherin neutralizing antibodies, and in genetic null mutants of cell polarity | 14, 15, 19, 20, 29 | Observed in the cortical walls within the VZ layer or more basally in embyos exposed to these agents |

| Heterotopia appearance | In FH, misplacement of β-III-tubulin+ cells within the glial layer seen; FH also associated with periventricular nodular heterotopia (gray matter nodules protuding into lateral ventricles) | 12, 23 | Columns of β-III-tubulin+ cells observed in cell adhesion genetic null mutant mice. Also abnormal protrusion of neurons into the 4th ventricle and closure of the spinal canal in myosin null mutants, consistent with nodular heterotopias | 17, 19 | Heterotopic β-III tubulin+ cells protruding into the lateral and 3rd ventricles were found in LPA and blood exposed embryos, forming nodular structures that caused narrowing and partial occlusion, particularly in the 3rd ventricle |

| Presence of ciliary defects | Loss of ciliated ependymal cells may explain, in part, altered CSF dynamics in FH | 25 | Loss of cilia function or structure occurring in either genetic deletion of cilia proteins or in ependymal cell loss by cell adhesion null mutants lead to development of FH | 26–28, 30 | LPA and blood component exposure caused in-complete loss of S100β+ ciliated ependymal cells, leading to cilia loss and aong cerebral ventricular walls |

| 3rd ventricle occlusion or aqueductal stenosis | Occlusion or stenosis appear as protrusions of cells from the ventricular wall into the ventricular spaces | 23, 25, 34 | Genetic deletion of cilia proteins and myosin II-B and IXa caused stenosis of the Sylvian aqueduct between the 3rd and 4th ventricles, as well as the spinal canal. This aqueductal block-age also occurred in the H-Tx rat model of hydrocephalus | 17, 18, 27, 45 | LPA and blood component exposure caused nodular protrusions within the lateral ventricle and 3rd ventricle, producing partial occlusion of these structures |

The reference list is not meant to be an exhaustive review of the literature.

Fig. 2. Exposure of mouse embryos to LPA induces FH.

Shown are data from mouse embryos cortically injected at embryonic day 13.5 (E13.5) with LPA (B, E, F, H, I, K, L, O, P, Q (magnified in F, I, L, Q) or vehicle control (A, D, G, J, M, N). (A–C) Ventricular dilation. Embryos injected with LPA (analyzed at E14.5) showed dilation of the lateral ventricles compared to embryos injected with vehicle (dotted outlines indicate ventricles), with changes quantified in (C) (n = 3 embryos per condition, average ± s.d., P = 0.006, P = 0.005, unpaired t test; Ipsi = ipsilateral, Contra = contralateral). (D–F) Cortical disruption. LPA exposure (analyzed at E14.5) produced cortical disruption of ventricular zone (VZ) organization and protrusions of NPCs along the apical ventricular surface (boxed area magnified in F). (G–I) Neural progenitor cell clusters in the lateral ventricles. Clusters of neural progenitor cells protrude from the apical VZ surface and can be found as isolated clusters throughout the ventricle (analyzed at E18.5). (J–L) Neurorosettes. These LPA-induced structures are composed of radially-oriented NPCs located throughout the VZ. (M–Q) Partial occlusion of the 3rd ventricle. Disruption of the 3rd ventricular wall, associated with partial ventricular occlusion was observed (analyzed at E14.5 in M, O, Q, see arrow; or E18.5 in N, P) v = ventricle, scale bars = 200 μm (A, B, D, E, G, H, J, K, M, N, O, P) and 50 μm (F, I, L, Q).

LPA exposure disrupts neural progenitor cell function

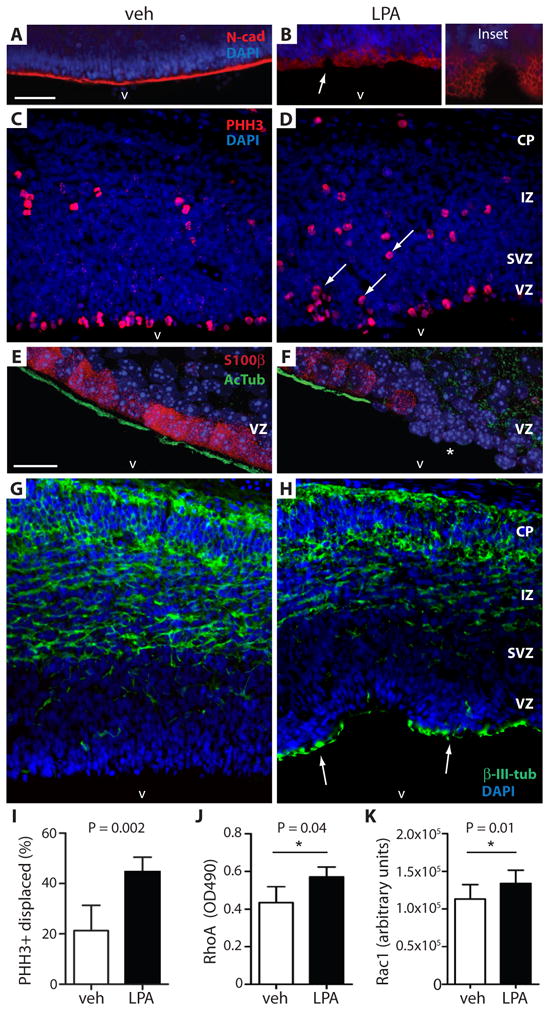

Cell adhesion molecules required for the formation of adherens junctions between cells help to maintain the luminal integrity of the cerebroventricular system. Knockout or knockdown of various molecular components that maintain ventricular integrity such as N-cadherin (14, 15), Celsr 2 and 3 (cadherin EGF LAG seven-pass G-type receptor types 2 and 3) (16), myosin II-B (17), myosin IXa (18), Lgl1 (lethal giant larvae 1) (19), and Dlg5 (discs, large homolog 5) (20) all produce histological features found in humanhydrocephalus (Table 1). LPA has been shown to both increase and decrease cell-cell contacts mediated by N-cadherin in a cell-type and receptor-subtype specific manner (13, 21). This suggests that modulation of LPA signaling may affect the integrity of the brain’s ventricles. The apical surface of the lateral ventricles was examined for N-cadherin expression that was found to be discontinuous in LPA-exposed mouse embryos but not vehicle control-treated embryos (Fig. 3, A and B). Consistent with N-cadherin’s function in maintaining the correct attachment of dividing NPCs to the apical surface (15), LPA-injected embryos showed a significant increase in the incorrect upward and basal positioning of mitotic cells (Fig. 3C, D, and I; P = 0.002, unpaired t test). In addition, clusters of NPC spheres (Fig. 2, H and I) (29 ± 7.1 per LPA-exposed embryo) were observed floating within the ventricles of LPA-treated embryos. This is consistent with the finding of NPCs in the CSF of newborns with post-hemorrhagic hydrocephalus (22).

Fig. 3. Cell and molecular effects of LPA exposure.

Exposure of mouse embryos to LPA results in displacement of mitotic neural progenitor cells, produces heterotopias that are incorrect cell locations, and activates Rho/Rac signaling. (A, B) Exposure to LPA, but not vehicle (analyzed at E14.5), disrupted the apical ventricular surface and altered N-cadherin expression (N-cad, red; arrow magnified in inset). Cell nuclei are counterstained with DAPI (blue). (C, D) The displacement of mitotic neural progenitor cells was identified by immunolabelling phosphorylated histone H3 (PHH3+, red). Displaced mitotic cells are abnormally positioned superficially in the VZ (D, arrows; LPA treated) rather than along the ventricular surface as in C (vehicle treated). (E, F) Immunolabeled ependymal cells of the VZ (S100β+, red) show loss of their cilia (AcTub+, green) after LPA exposure (F) compared to vehicle controls (E) when analyzed at postnatal day 4. LPA exposure decreased the number of S100β+ ependymal cells resulting in loss of cilia from the ventricular surface (asterisk, F). (G, H) Postmitotic neurons identified by immunolabeling with β-III-tubulin (β-III-tub+, green) indicated VZ disruption in regions of the cortex exposed to LPA and the presence of heterotopic neurons (H, arrows) compared to vehicle control (G). (I) Quantification of mitotically-displaced neural progenitor cells identified by PHH3 immunolabeling (n = 5 embryos per condition, average ± s.d., unpaired t test, ** P = 0.0022). (J, K) Quantification of RhoA and Rac1 activation in ex vivo mouse embryonic cortex following exposure to LPA or vehicle for 3 min. Ex vivo culture involved dissection and removal of whole cortical hemispheres from E13.5 embryos for growth in cell media with timed exposure to either condition. RhoA: n = 5 pairs of matched cortical hemispheres exposed to vehicle or 10 μM LPA; average ± s.d., P = 0.0408, paired t test. Rac1: n = 6 pairs matched cortical hemispheres exposed to vehicle or 10 μM LPA, average ± s.d., paired t test, P = 0.01. CP = cortical plate, IZ = intermediate zone, SVZ = subventricular zone, VZ = ventricular zone. Scale bars = 50 (A–D, G, H) and 20 μm (E, F).

A cause of hydrocephalus is loss of cilia or ciliary function on the ependymal cells lining the ventricular surface, where the cilia are thought to reduce the flow of CSF along the ventricle walls (23–30). Ependymal cells differentiate during mid to late neurogenesis in the developing brain, and mature in early postnatal life to form a single multi-ciliated cell layer that can be identified by immunostaining for S100β and acetylated α-tubulin (31). Following exposure of mouse embryos to LPA, alterations in ependymal cells were observed at postnatal day 4. Incomplete loss of mature ependymal cells, identified by the co-absence of S100β and acetylated α-tubulin immunoreactivities, manifested as discrete stretches of missing cells (Fig. 3, E and F, and videos S1 and S2). These results are consistent with the loss, or denudation, of ependymal cells in both clinical cases and mouse models of FH (25, 29).

LPA activates Rho and Rac in the embryonic cortex

LPA receptors, particularly LPA1, are powerful activators of the small GTPase Rho (32), as well as the closely related GTPase, Rac (33). To determine the possible involvement of these pathways in LPA-induced FH, Rho and Rac signaling were examined using ex vivo cerebral cortical cultures grown in the presence or absence of LPA, followed by measurements using an ELISA assay. There was activation of both prototypical members RhoA (n = 6 pairs, P = 0.04, paired t test) and Rac1 (n = 6 pairs, P = 0.01, paired t test) in the embryonic cortex (7) after LPA stimulation (Fig. 3, J and K, and fig. S6A–C). These results confirm the activation of both Rho and Rac by LPA signaling in the mouse embryonic cerebral cortex under conditions that could promote FH.

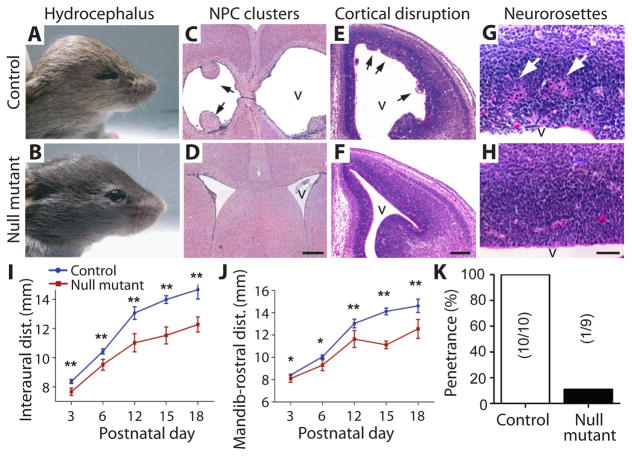

Serum, plasma, and LPA induce LPA receptor-dependent FH

Several blood-related factors such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) have been reported to be elevated in CSF from hydrocephalic individuals (34). When administered to young mice, these growth factors can cause ventricular dilation and hydrocephalus (35). This raised the possibility that factors in addition to LPA, present in plasma and serum, could be responsible for producing FH and associated histological changes observed in this mouse model. To address this question, mouse embryos with genetic deletion of specific LPA receptors were injected with plasma, serum, or LPA and were then assessed pre- and post-natally. Based on gene expression studies, LPA1 and LPA2 were expressed in the NPC population of the VZ (figs. S7A–L and S8, A and B) and are known to be coupled to the same G proteins that mediate LPA signaling (9, 36). To minimize receptor compensation, LPA1 and LPA2 double-null mutant mice (LPA1−/− LPA2−/−) were examined together with LPA2 homozygous null/LPA1 heterozygote (LPA1+/− LPA2−/−) mice. Both LPA1−/− LPA2−/− and LPA1+/− LPA2−/− mouse embryos were exposed to plasma, serum, or LPA. These analyses revealed that exposure to these agents in LPA1+/− LPA2−/− mice produced results indistinguishable from wildtype controls, indicating a primary role for the LPA1 receptor in the induction of FH (Fig. 4A–K, fig. S9A–G, table S1, and table S2). Both wildtype and LPA1+/− LPA2−/− mice were subsequently used as controls and compared to double-null mutant animals. Both plasma and serum induced cortical disruption that was abrogated in double-null mutant mice (fig. S1A, B, D, and E). Critically, LPA’s ability to induce FH and associated histological changes (Table 1 and table S1) was strongly dependent on the expression of LPA1. In LPA1+/− LPA2−/− control animals exposed to LPA, FH showed complete penetrance (n = 10, 100%). In contrast, FH was reduced to approximately 10% in double-null mutant mice (n = 9, 11%) (Fig. 4K, fig. S9A–G, and table S1). The rare occurrence of FH in double-null mutant animals likely reflects contributions by one or more of the remaining four LPA receptors rescuing the double-null phenotype. These data suggest that FH, along with associated histological changes, induced by plasma, serum, or LPA exposure, is primarily dependent on the LPA1 receptor.

Fig. 4. LPA does not induce hydrocephalus in LPA1/LPA2 receptor double-null mice.

(A, B) Head dilation and hydrocephalus are observed in postnatal animals after LPA exposure at E13.5 in control (LPA1+/− LPA2−/−) (A) but not double-null mutant mice (LPA1−/− LPA2−/−) (B). (C–H) LPA-injected positive control animals showed neural progenitor cell clusters (C, arrows), early cortical disruption at E14.5 (E, arrowheads), and neurorosettes (G, arrows); these were generally absent (see K) in double-null mutant mice exposed to LPA (D, F, H). (I, J) LPA exposure in control mice (n = 10, blue line) revealed increased interaural (I) and mandibular-rostral distance (J) as early as postnatal day 3 that was attenuated in the double null mutant animals (n = 9, red line) (see Fig. 1, wildtype LPA exposure) (n ≥ 3 embryos per genotype, average ± s.d., unpaired t-test, P < 0.05, see table S2) (K) Penetrance of LPA-induced hydrocephalus was quantified; numbers in parentheses represent number of hydrocephalic animals/total cohort. v = lateral ventricle. Scale bars = 400 μm (C, D), 200 μm (E, F), and 50 μm (G, H).

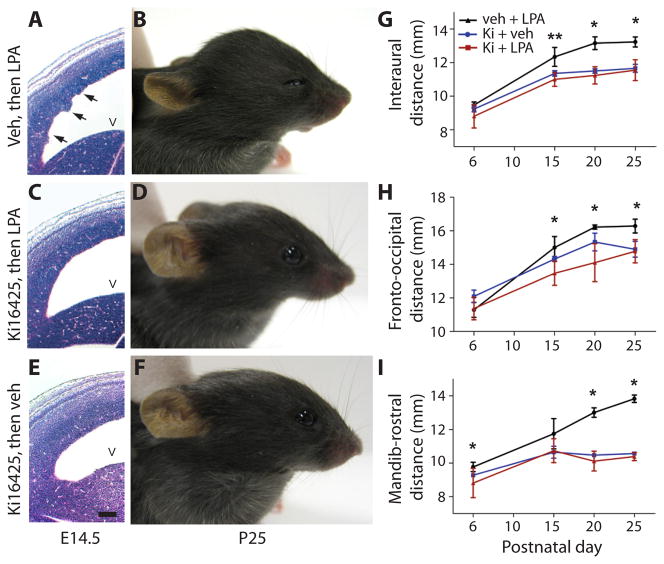

Pharmacological LPA1 receptor blockade prevents FH and histological changes

The identification of LPA receptor signaling as a potential initiating cause of FH suggested that pharmacological modulation of LPA receptors could influence the development of FH. Ki16425, a receptor antagonist with proven specificity against LPA1 and LPA3 (37), was intraventricularly injected prior to LPA exposure. Available genetic and expression data did not support a role for LPA3 in LPA-induced FH (38, 39). Mouse embryos that were treated with vehicle followed by LPA showed similar cortical defects compared to mice treated with LPA only (n = 5) (Fig. 5A and B). In contrast, mouse embryos treated with Ki16425 followed by LPA showed a dramatic reduction in FH and related histological changes (n = 5) (Fig. 5C, D, G–I). As a control, treatment with Ki16425 followed by vehicle produced no such effects (n = 4) (Fig. 5E–I). These data demonstrate that pharmacological intervention targeting LPA receptors, particularly LPA1, could attenuate development of LPA-induced FH. These pharmacological studies on wildtype mice independently support the results obtained with the receptor-null mice and also eliminate the possibility that constitutive receptor deletion producesdevelopmental artifacts that somehow prevent FH.

Fig. 5. Hydrocephalus can be blocked by an LPA1 receptor antagonist.

Mouse embryos were injected sequentially with vehicle followed by LPA 10 min later at E13.5 and were examined at embryonic day 14.5 (A, E14.5) or were assessed for hydrocephalus postnatally (B, postnatal day 25). Pharmacological intervention with the Ki16425 (Ki) antagonist of LPA1 and LPA3 receptors was assessed in the same way but replacing vehicle with Ki16425 followed by LPA, and then analyzing the animals during embryonic development (C) and postnatally (D). The effects of antagonist alone were assessed using Ki16425 followed by vehicle, and then embryonic and postnatal assessment for hydrocephalus (E, F). Apical protrusions of ventricular cell clusters (A, arrows) were observed 24 hours later in embryos injected with vehicle and then LPA but not in embryos injected with drug and then LPA, or drug then vehicle (C, E). (G–I) Quantitative assessments measured head dimensions in positive controls and animals exposed to drug. Positive controls (animals exposed to vehicle then LPA) showed the expected changes in head dimensions and hydrocephalus (black lines, G–I). In each set of head dimension measurements, statistically significant increases were observed in vehicle+LPA treated mice compared with the normal head measurements obtained with drug+LPA treated animals (red and blue lines, G–I). No statistically significant changes were observed between drug and vehicle (blue line) and drug and LPA (red line) injected embryos (n ≥ 3 embryos per condition, average ± s.d., unpaired t-test, P > 0.05, see table S2). v = lateral ventricle. Scale bar = 100 μm.

Discussion

In this study, we generated a novel mouse model of fetal hydrocephalus through embryonic exposure to blood components or the bioactive lipid LPA. Using this model, we showed that the histological consequences of FH occurred mainly through the LPA1 signaling pathway in NPCs within the developing cerebral cortex, and that these effects could be blocked by either genetic removal or pharmacological inhibition of this G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR). We propose that LPA1 signaling is a molecular mechanism that may account for the epidemiological observations linking prenatal bleeding and FH (Fig. 6). Intracranial hemorrhage into the germinal matrix (or VZ layer) of the developing cerebral cortex and CSF results in abnormally high levels of LPA that over-activate LPA receptors expressed on NPCs. This in turn over-activates downstream intracellular signaling components to produce disorganization and thinning of cortical layers and ultimately FH (Fig. 6). Additional histological consequences of LPA receptor over-activation include NPC cluster formation, 3rd ventricular occlusion, and cilia loss along the lateral ventricular walls. How these changes relate precisely to each other remains to be determined. Additional endpoints such as CSF overproduction and elevated intracranial pressure, remain to be tested in this model, particularly as they relate to these histological changes. Aberrant activation of LPA receptors may explain the diverse histological presentation reported for human FH, and is consistent with other FH-relevant animal models (Table 1). Based on genetic and pharmacological studies, the primary receptor mediating these effects is LPA1 with comparatively minor contributions by other LPA receptor subtypes. Although other contributory factors in addition to LPA may be present in blood, genetic deletion of LPA receptors prevented plasma and serum from inducing FH. This suggests a primary role for receptor-mediated LPA signaling in the development of FH.

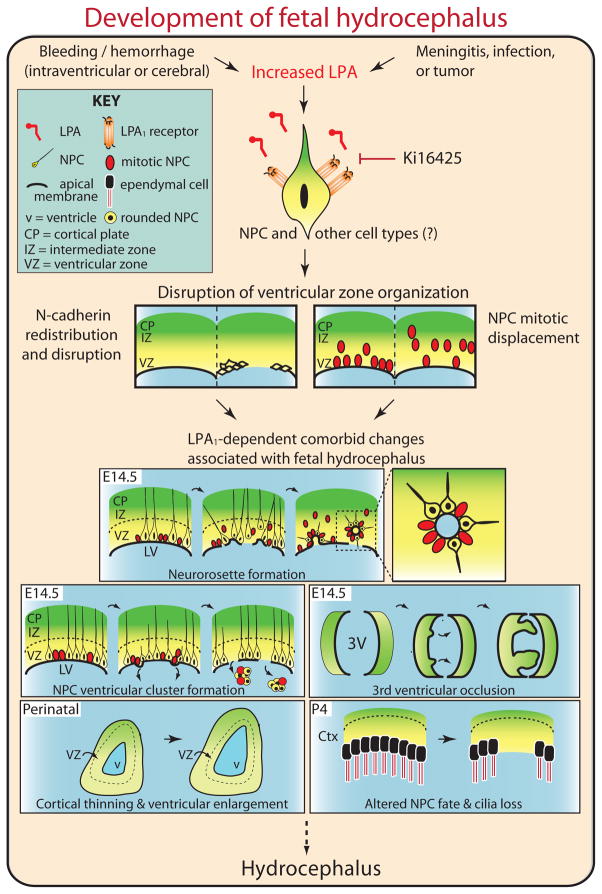

Fig. 6. Model for how LPA could induce FH.

Intraventricular hemorrhage may lead to an increase in the concentration of LPA in the brain resulting in aberrant activation of LPA1 receptors on neural progenitor cells with concomitant activation of downstream G protein signaling components such as the GTPases Rho and Rac. The ensuing disruption of adherens junctions between neuroprogenitor cells results in their mitotic displacement in the ventricular zone, subsequent histological alterations including neurorosette formation, and formation of neural progenitor cells into ventricular clusters. This results in occlusion of the 3rd ventricle, cortical thinning, ventricular enlargement, altered neural progenitor cell fate and loss, which together result in fetal hydrocephalus (FH). Pharmacological blockade of LPA1 receptor signaling using the LPA1 receptor antagonist Ki16425 prevents aberrant activation of this signaling cascade in response to LPA and the formation of FH.

A variety of gene mutations in animals have been reported to result in FH. LPA signaling has been documented to interface with many of these genes and their activated pathways. FH has been linked to cadherins (15, 20), adhesion molecules that are altered by LPA signaling (40). Loss of myosin IIB and IXa both result in hydrocephalus, consistent with participation of myosin pathways in the developing CNS and their modulation by LPA signaling (41). The small GTPase Rho that is activated by LPA (13, 36) has also been linked to FH (18). We showed that this signaling component, along with its partner Rac, was activated in the cerebral cortex of mouse embryos exposed to LPA. Through its presence in blood, LPA thus has the potential to modulate one or more molecular pathways that have been linked to FH.

Genetic deletions in cilia-related proteins, such as Polaris (Tg737), Stumpy, or Hydin (24, 26, 27, 30), or mutations leading to primary ciliary dyskinesia (42), have been implicated in FH suggesting that loss of cilia my contribute to the development of this disorder. The loss of cilia observed in the current study, which appears to result from disruption of neural progenitor cells, is consistent with altered cell fate whereby ciliated ependymal cells are reduced due to death of NPCs or their differentiation into non-ciliated cell types (29). This phenomenon of ciliary loss complements prior genetic data and connects the action of LPA (through pathological exposure of the cerebral cortex to blood) to dysfunction of NPCs and loss of ciliated ependymal cells in FH.

In prior work, over-activation of LPA signaling using an ex vivo organotypic cerebral cortical culture of fetal brain produced major disruption of NPCs and gross disorganization of the cortex that included cortical folding resembling polygyrations. This ex vivo method relied on the dissection, separation, and culturing of intact cortical hemispheres in the continuous presence of LPA. However, its limited survival time (~20 hours) prevented multi-day and prenatal vs. postnatal comparisons. In contrast, we were able to recapitulate ventricular dilation and other histological changes observed in human FH through the in vivo system reported here (9). Both in vivo and ex vivo data implicated displacement of NPCs as a causative factor in FH (Fig. 3) (9). Contrasting effects observed between the in vivo and ex vivo studies can be explained by the existence of additional elements such as growth factors and cytokines in our in vivo system that are known to influence neurogenesis and formation of the cerebral cortex (43, 44). Blockage of CSF flow (not duplicated in ex vivo cultures) may also contribute to FH (45). Other differences between in vivo and ex vivo studies include localized ventricular versus whole brain exposure to LPA and single bolus versus prolonged exposure to LPA, respectively. Despite these differences, the acute disruption of mitotic NPCs and its dependence on LPA1 was conserved between the in vivo and ex vivo studies. Intriguingly, some hydrocephalic patients have also been reported to exhibit cortical polygyrations, consistent with the effects seen during prolonged ex vivo cortical exposure to LPA (46).

The cellular alterations that resulted in dilated ventricles, neurorosettes, ventricular disruption and occlusion, and cilia loss are likely due to the direct effects of LPA receptor activation on NPCs in the VZ rather than on secondary effects that result from hemorrhage or the actions of other factors in blood. First, intraventricular exposure to plasma or serum can induce FH in some but not all exposed mouse embryos. However, FH was absent in LPA1−/− LPA2−/− double-null mice indicating that non-LPA blood products, if present, played a minor role in inducing FH. Second, at the age that mouse embryos were exposed to LPA (E13.5), the LPA1 receptor is expressed primarily by NPCs in the VZ (Fig. S7A–L) (7). The observed histological defects were inconsistent with primary disruption involving the diffuse organization of blood vessels throughout the cerebral wall (38, 47), which should have produced effects throughout the cortex and non-cortical neuraxis where blood vessels are also present. The LPA1 receptor is also expressed in the superficial marginal zone (future layer 1 of the cortex) and developing meninges at E13.5 (fig. S7E, G, I), leaving open possible contributions by the cells in these regions to FH. Third, pharmacological antagonism of the LPA1 receptor prevented LPA-induced FH. This result eliminates the possibility that developmental perturbations of NPCs or blood vessels induced by loss of LPA1−/− and LPA2−/− prevented development of FH. The precise roles of individual LPA receptor subtypes on defined cells in FH remain to be determined.

Several potential limitations of this in vivo model should be mentioned. First, the progression of cortical brain development in mice is similar but not identical to the extended course in humans. Second, the spatiotemporal extent of intracranial hemorrhage and severity of exposure to blood in fetuses is not well-delineated; thus this bolus exposure model likely only approximates the spectrum of pathological insult during human fetal hydrocephalus. Future translational studies focused on patient samples may help refine this model. While this study focused on a preventative strategy in which the LPA1 antagonist was delivered prior to LPA exposure, there was likely considerable temporal overlap between the accessibility of both antagonist and LPA. Furthermore, we note that NPC loss and ventricular dilation occurred prenatally but progressed to severe hydrocephalus only at neonatal ages, indicating that FH progression may occur in stages, as reported in humans (25). This underscores the feasibility of a therapeutic strategy whereby early prenatal diagnosis of intracranial hemorrhage or ventricular dilation could be ameliorated by short-term LPA receptor modulators without damaging LPA-mediated, normal cortical development while reducing or preventing hydrocephalus.

The identification of LPA signaling in the initiation of FH is consistent with a diverse range of reported risk factors that share FH as a common endpoint. Reported risk factors include bleeding, infection, meningitis, and brain tumors, all of which have been associated with increased LPA signaling (48–50). The disparate histological phenomena associated with human FH (Table 1) can be reproduced by exposure of embryonic mouse brain to LPA, supporting a shared molecular mechanism in both mice and humans. The ability to prevent FH by pharmacologically blocking LPA signaling suggests that LPA and the LPA1 receptor have potential as therapeutic targets for treating at least some forms of FH. Whether other forms of FH are amenable to this treatment strategy requires further study. Finally, it is notable that a host of developmentally linked disorders including cerebral palsy (51), schizophrenia (52), and autism (53) have also been epidemiologically associated with prenatal bleeding suggesting that future studies should investigate a potential connection between aberrant LPA signaling and these neurodevelopmental disorders.

Material and Methods

Injection solutions

18:1 LPA (Avanti Polar Lipids) solution (10 mM in HBSS (Hank’s buffered salt solution)) was prepared fresh just prior to use by ultrasonication in a water bath (Branson) for 15 minutes at 22°C. Whole blood was obtained from female adult mice by cardiac puncture collection and clotted for 1 hour on ice. The clot was manually removed and the remaining solution spun down at 2000 rpm for 20 min at 4°C. The top “serum” and bottom “red blood cell” (washed and resuspended in HBSS) fractions were collected by centrifugation separation. The “plasma” fraction was obtained as previously described (11). Ki16425 (Kirin Brewery, 1 mM final concentration in HBSS), ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (Sigma, 2 mM final concentration), and Rac inhibitor NSC23766 (EMD Chemicals, 10 mM final concentration) were prepared for intraventricular injections. BrdU solution was prepared (Sigma, 100 mg/kg final concentration) for intraperitoneal injection.

Injections

All procedures followed proper animal use and care guidelines that were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at The Scripps Research Institute. In utero injections of 3 μl vehicle (HBSS), plasma, serum, RBC, or LPA solutions into embryonic cortices were performed on pentobarbital anesthesized (Nembutal, 50 mg/kg), timed-pregnant dams at E13.5. Embryos were examined after 1 day (E14.5), 5 days (E18.5), or postnatally at P4, P10, P21, and 4 weeks. For Ki16425 intervention experiments, E13.5 embryonic cortices were injected with 1.5 μl Ki16425, exposed for 15 minutes, then subsequently injected ipsilaterally with 1.5 μl LPA solution, sutured, and examined 1 day later. For postnatal assessment, pups were allowed to be birthed naturally. Since uterine positional order was lost during delivery, all embryos within each litter were injected with identical ligands. Pharmacological studies were performed using 1.5 μl of each ligand to maintain consistent injection volumes across studies.

Histology

Pregnant dams were intraperitoneally anesthesized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg), during which the embryos were collected whole by surgical dissection, decapitated, and heads fixed in formalin-alcohol-acetic acid solution (FAA) or 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Subsequently, the anesthesized dams were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. Naturally birthed pups were anesthesized with pentobarbital and transcardially perfused with FAA or PFA. Their brains were immersion fixed with FAA or PFA, paraffinized using an automated processor (Sakura), and embedded in paraffin. The tissue was sectioned (6–10 μm thickness), dewaxed, and stained using hematoxylin and eosin. Only healthy embryos with observable heartbeats were analyzed (≥ 95% injected).

Immunofluorescence

Brains preserved in FAA or PFA were examined. Sucrose cryoprotected/frozen heads fixed in PFA were sectioned (16 μm), blocked with species-appropriate serum, and immunolabeled. Paraffin sections (6–10 μm) were additionally dewaxed and processed through sodium citrate buffer (10 mM, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 6.0) antigen retrieval prior to antibody staining. Antibodies specific for the following antigens were used in overnight staining at 4°C: nestin (BD Biosciences, mouse, 1:400), β-III-tubulin (Covance, mouse, 1:1000), phosphorylated histone H3 (Ser10) (Millipore, rabbit, 1:1000), S100β (Abcam, rabbit, 1:500), acetylated-α-tubulin (Sigma, mouse, 1:1000), N-cadherin (Calbiochem, rabbit, 1:200), and BrdU (Roche, rat, 1:50). Mouse, rabbit, or rat-specific secondary antibodies conjugated with AlexaFluor 488 or Cy3 (Invitrogen or Jackson Immunoresearch, donkey, 1:1000) were used for visualization. Nuclei were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Sigma).

Image acquisition and quantification

Epifluorescence images were acquired on a Zeiss Imager 1D microscope (Axiovision 4.7.2 software) using appropriate fluorescence filters. Confocal images were acquired on an Olympus Fluoview 500 laser scanning microscope using appropriate lasers and optimized Z steps, sequential channel acquisition, and Kalman filtering of 4. Confocal image stacks were analyzed and reconstructed into videos using Metamorph software (version 7, Molecular Devices). Images and manual counting were analyzed by investigators blinded as to sample identity. Inadvertent loss of blinding occurred when differences between control and experimental samples were dramatically obvious but would not have altered the basic interpretation and results of this study. Photoshop adjustments (version 11.0, Adobe) were strictly limited to light level and contrast enhancement for visual aesthetics that did not change data interpretation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism software (version 5, Graphpad). Normality of data distribution was tested using the F-test for unequal variance. Normally distributed data was analyzed using unpaired or paired Student’s t test when comparing between two data groups. Non-normally distributed data was analyzed using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney test and Kruskal-Wallis and Dunnett’s post hoc tests when comparing between two and three data groups, respectively. Data were expressed as average ± standard deviation (s.d.) and considered significant if tests indicated P ≤ 0.05.

Head size measurement

Increased head circumference, clinically used as a standard indicator of hydrocephalus, is typically measured using a cloth tape above the ears, but is not technically feasible nor accurately reproducible in early postnatal mice due to small size and incomplete skull calcification. Instead, an electronic caliper (C-master digital gauge) was used to perform three uni-dimensional measurements: interaural distance (ear-to-ear), madibular-rostral distance (jaw-to-top of the head), and fronto-occipital distance (forehead-to-back of the head). Individual measurements were performed in triplicate and averaged. Measurements were performed at postnatal days P3, P6, P10, P12, P15, P18, P20, P25, and P30. Postnatal animals were tattooed for individual identification.

Ventricle area measurement

Paraffinized embryo heads in coronal presentation were serially cut (10 μm thickness). Sections at 100 μm intervals from anterior to posterior were imaged. Lateral ventricles were manually traced, area sizes calculated automatically using Axiovision software (version 4.7.2, Carl Zeiss), and tabulated. At least 6 sections were measured per embryo.

Construction and labeling of in situ hybridization probes

Mouse Lpar1 Exon 3 was amplified by PCR from a BAC template using Pfx50 DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) using the following primers, A1Ex3For: 5′-TTCACAGCCATGAACGAACAAC-3′ and A1Ex3Rev: 5′-ACCAAGCACAATGACCACAGTC-3′, and tailed with Taq polymerase. The 748 bp product was then isolated using the Qiaex II DNA isolation kit (Qiagen), cloned into the pGem-T Easy T vector (Promega), and linearized with appropriate restriction enzymes. DIG labeled sense and antisense runoff transcripts were transcribed using DIG labeling mix (Roche) and SP6 and T7 RNA polymerases (Roche), respectively. DIG-labeled sense and antisense mouse Lpar2 probes were prepared as previously described (38).

In situ hybridization

Embryo heads were examined for Lpar1 and Lpar2 expression as previously described (7). Paraffin sections were dewaxed and rehydrated using DEPC-treated solutions prior hybridization. All probes were hybridized at 65°C.

RhoA and Rac1 activation ELISA assay

Fresh embryonic cortical hemispheres were dissected out in ice-cold Opti-MEM (Invitrogen). Matched hemispheres were cultured in media supplemented with 10 μM LPA and 0.1% fatty-acid free bovine serum albumin (FAFBSA) or without LPA, essentially as previously described (9, 54). LPA stimulation was terminated in ice-cold Opti-MEM without LPA. The cortical wall was dissected away from the ganglionic eminences, triturated in lysis buffer, and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Activation of RhoA and Rac1 were measured using absorbance- or chemoluminescence-based G-LISA kits, respectively, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Cytoskeleton) using an EL800 microplate reader and a SynergyMX luminometer (Bio-Tek). Antibody concentrations were optimized for machine sensitivity. Statistically significant but modest activation levels likely reflect the absence of serum starvation, used to approximate in vivo conditions, along with the influence of other endogenous signaling pathways that increase the basal activation of Rho and Rac.

LPA measurements

The LPA extraction method was adapted with some modification (55). Briefly, 50 μl of tissue homogenate (final concentration 200–400 mg/ml fresh tissue) was used for each sample. 187.5 μl of methanol:HCl 10:1 mixture and 625 μl of methyl-tert-butyl ether (MTBE) were added to each sample and incubated on a nutator at 22°C for one hour. 157 μl of distilled water was then added to the mixture, incubated for 10 minutes, and phase-separated by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 minutes. The initial organic phase was collected, while the aqueous phase was re-extracted with 250 μl of MTBE:methanol:H2O (10:3:2.5 ratio). Both organic phases were combined and dried using a Speedvac concentrator (Savant), and resuspended in 100 μl methanol. Non-natural 17:0 LPA (Avanti Polar Lipids) was added as an internal standard. The extracts were subjected to liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) for LPA measurement at the TSRI Mass Spectrometry Core using an Agilent 6410 triple quad mass spectrometer coupled to an Agilent 1200lc stack. Compounds were eluted with a mobile phase of H20/ACN 90:10 with 10 mM NH4OAc (A) and ACN/H2O with 10 mM NH4OAc (B) at 0.2 ml/min. Agilent 300SB-C8 2.1 mm x 100 mm, 3.5 μm columns were used. The gradient was t = 0, 80:20 (A:B), t = 5 50:50, t = 7 25:75, t = 15 0:100, t = 20 off. There was a 5 min re-equilibration time between samples. The source was maintained at 350°C with a drying gas flow of 10 liters/hour, and data were collected in negative ion mode. The following transition states were monitored: 18:1 LPA m/z ratio 435 → 153, 17:0 LPA m/z 423 → 153. Calibration curves were generated using 10–10,000 fmol/injection of 18:0 LPA. Peak areas of [M-H] for LPA (18:1) form were normalized to the internal standard and plotted versus concentration.

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1. Serum and plasma but not RBCs produce LPA receptor dependent cortical wall disruption.

Fig. S2. Experimental parameters of LPA cortical exposure model.

Fig. S3. Lack of fronto-occipital changes and survival curve of LPA injected animals that develop hydrocephalus over time.

Fig. S4. Bilaterally increased ventricular area and mitotic displacement following LPA exposure.

Fig. S5. LPA exposure induces the formation of denuded cell clusters that originate from the ventricular zone of the developing cortex.

Fig. S6. LPA induces RhoA and Rac1 activation.

Fig. S7. Expression of Lpar1 in the developing embryonic brain at E13.5.

Fig. S8. Expression of Lpar2 in the developing embryonic brain at E13.5.

Fig. S9. LPA-induced cortical disruption and mitotic displacement are abrogated in double-null mutant mice.

Table S1. Histological features associated with hydrocephalus are abrogated in LPA1 and LPA2 double-null animals.

Table S2. Average ± s.d., n, and P-values of data graphed in Figs. 1, 4, and 5.

Video S1: Ciliated ependymal cells are maintained at the apical ventricular surface after vehicle exposure.

Video S2: Ciliated ependymal cells are lost in a patchy fashion at the apical ventricular surface after LPA exposure.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Kennedy and D. Trajkovic for in situ hybridization and histological assistance, B. Webb and G. Siuzdak for assistance with mass spectrometry, K. Spencer for confocal microscopy assistance, W. Balch and M. McHeyzer-Williams for use of equipment, B. Pham and D. Chiu for slide preparation, members of the Chun lab for discussions and support, D. Letourneau for editorial assistance, S. Liu for supplying a custom syringe for injections, and Kirin Brewery for providing Ki16425.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants MH051699, NS048478, Scripps Translational Science Initiative grant U54 RR025774 (JC), and an NSF predoctoral fellowship (YCY). YCY is currently a Hydrocephalus Association Mentored Young Investigator.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Y.C.Y. and J.C. designed the research, Y.C.Y performed head size measurements and examined tissue via in situ hybridizations, Y.C.Y. and T.M. performed animal experiments and examined the tissue, M-E.L. optimized and prepared lipid extracts for measurements, Y.C.Y and K.N. performed Rac and Rho ELISA measurements, R.R.R. generated the receptor-null animals, Y.C.Y, J.W.C, and M.A.K. blindly quantified mitotic displacement and ventricular size, Y.C.Y. performed data analysis, and Y.C.Y. and J.C. wrote the paper.

Competing interests: J.C. is a scientific advisory board member for Amira Pharmaceuticals. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References and Notes

- 1.Persson EK, Anderson S, Wiklund LM, Uvebrant P. Hydrocephalus in children born in 1999–2002: epidemiology, outcome and ophthalmological findings. Childs Nerv Syst. 2007;23:1111–1118. doi: 10.1007/s00381-007-0324-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shooman D, Portess H, Sparrow O. A review of the current treatment methods for posthaemorrhagic hydrocephalus of infants. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res. 2009;6:1. doi: 10.1186/1743-8454-6-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang J, Williams MA, Rigamonti D. Genetics of human hydrocephalus. J Neurol. 2006;253:1255–1266. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0245-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aoki J, Taira A, Takanezawa Y, Kishi Y, Hama K, Kishimoto T, Mizuno K, Saku K, Taguchi R, Arai H. Serum lysophosphatidic acid is produced through diverse phospholipase pathways. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48737–48744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206812200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi JW, Herr DR, Noguchi K, Yung YC, Lee CW, Mutoh T, Lin ME, Teo ST, Park KE, Mosley AN, Chun J. LPA receptors: subtypes and biological actions. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;50:157–186. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yanagida K, Masago K, Nakanishi H, Kihara Y, Hamano F, Tajima Y, Taguchi R, Shimizu T, Ishii S. Identification and characterization of a novel lysophosphatidic acid receptor, p2y5/LPA6. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:17731–17741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808506200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hecht JH, Weiner JA, Post SR, Chun J. Ventricular zone gene-1 (vzg-1) encodes a lysophosphatidic acid receptor expressed in neurogenic regions of the developing cerebral cortex. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1071–1083. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.4.1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noguchi K, Herr D, Mutoh T, Chun J. Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) and its receptors. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kingsbury MA, Rehen SK, Contos JJ, Higgins CM, Chun J. Non-proliferative effects of lysophosphatidic acid enhance cortical growth and folding. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1292–1299. doi: 10.1038/nn1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Estivill-Torrus G, Llebrez-Zayas P, Matas-Rico E, Santin L, Pedraza C, De Diego I, Del Arco I, Fernandez-Llebrez P, Chun J, De Fonseca FR. Absence of LPA1 signaling results in defective cortical development. Cereb Cortex. 2008;18:938–950. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cherian SS, Love S, Silver IA, Porter HJ, Whitelaw AG, Thoresen M. Posthemorrhagic ventricular dilation in the neonate: development and characterization of a rat model. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:292–303. doi: 10.1093/jnen/62.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheen VL, Basel-Vanagaite L, Goodman JR, Scheffer IE, Bodell A, Ganesh VS, Ravenscroft R, Hill RS, Cherry TJ, Shugart YY, Barkovich J, Straussberg R, Walsh CA. Etiological heterogeneity of familial periventricular heterotopia and hydrocephalus. Brain Dev. 2004;26:326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiner JA, Fukushima N, Contos JJ, Scherer SS, Chun J. Regulation of Schwann cell morphology and adhesion by receptor-mediated lysophosphatidic acid signaling. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7069–7078. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07069.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ganzler-Odenthal SI, Redies C. Blocking N-cadherin function disrupts the epithelial structure of differentiating neural tissue in the embryonic chicken brain. J Neurosci. 1998;18:5415–5425. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-14-05415.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadowaki M, Nakamura S, Machon O, Krauss S, Radice GL, Takeichi M. N-cadherin mediates cortical organization in the mouse brain. Dev Biol. 2007;304:22–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tissir F, Qu Y, Montcouquiol M, Zhou L, Komatsu K, Shi D, Fujimori T, Labeau J, Tyteca D, Courtoy P, Poumay Y, Uemura T, Goffinet AM. Lack of cadherins Celsr2 and Celsr3 impairs ependymal ciliogenesis, leading to fatal hydrocephalus. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:700–707. doi: 10.1038/nn.2555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma X, Bao J, Adelstein RS. Loss of cell adhesion causes hydrocephalus in nonmuscle myosin II-B-ablated and mutated mice. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2305–2312. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-01-0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abouhamed M, Grobe K, Leefa Chong San IV, Thelen S, Honnert U, Balda MS, Matter K, Bahler M. Myosin IXa Regulates Epithelial Differentiation and Its Deficiency Results in Hydrocephalus. Mol Biol Cell. 2009 doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-04-0291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klezovitch O, Fernandez TE, Tapscott SJ, Vasioukhin V. Loss of cell polarity causes severe brain dysplasia in Lgl1 knockout mice. Genes Dev. 2004;18:559–571. doi: 10.1101/gad.1178004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nechiporuk T, Fernandez TE, Vasioukhin V. Failure of epithelial tube maintenance causes hydrocephalus and renal cysts in Dlg5−/− mice. Dev Cell. 2007;13:338–350. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yanagida K, Ishii S, Hamano F, Noguchi K, Shimizu T. LPA4/p2y9/GPR23 mediates rho-dependent morphological changes in a rat neuronal cell line. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5814–5824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610767200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krueger RC, Jr, Wu H, Zandian M, Danielpour M, Kabos P, Yu JS, Sun YE. Neural progenitors populate the cerebrospinal fluid of preterm patients with hydrocephalus. J Pediatr. 2006;148:337–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fukumizu M, Takashima S, Becker LE. Neonatal posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus: neuropathologic and immunohistochemical studies. Pediatr Neurol. 1995;13:230–234. doi: 10.1016/0887-8994(95)00183-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banizs B, Pike MM, Millican CL, Ferguson WB, Komlosi P, Sheetz J, Bell PD, Schwiebert EM, Yoder BK. Dysfunctional cilia lead to altered ependyma and choroid plexus function, and result in the formation of hydrocephalus. Development. 2005;132:5329–5339. doi: 10.1242/dev.02153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dominguez-Pinos MD, Paez P, Jimenez AJ, Weil B, Arraez MA, Perez-Figares JM, Rodriguez EM. Ependymal denudation and alterations of the subventricular zone occur in human fetuses with a moderate communicating hydrocephalus. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:595–604. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000171648.86718.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dawe HR, Shaw MK, Farr H, Gull K. The hydrocephalus inducing gene product, Hydin, positions axonemal central pair microtubules. BMC Biol. 2007;5:33. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-5-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Town T, Breunig JJ, Sarkisian MR, Spilianakis C, Ayoub AE, Liu X, Ferrandino AF, Gallagher AR, Li MO, Rakic P, Flavell RA. The stumpy gene is required for mammalian ciliogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:2853–2858. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712385105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wodarczyk C, Rowe I, Chiaravalli M, Pema M, Qian F, Boletta A. A novel mouse model reveals that polycystin-1 deficiency in ependyma and choroid plexus results in dysfunctional cilia and hydrocephalus. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paez P, Batiz LF, Roales-Bujan R, Rodriguez-Perez LM, Rodriguez S, Jimenez AJ, Rodriguez EM, Perez-Figares JM. Patterned neuropathologic events occurring in hyh congenital hydrocephalic mutant mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:1082–1092. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31815c1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lechtreck KF, Delmotte P, Robinson ML, Sanderson MJ, Witman GB. Mutations in Hydin impair ciliary motility in mice. J Cell Biol. 2008;180:633–643. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200710162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spassky N, Merkle FT, Flames N, Tramontin AD, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Adult ependymal cells are postmitotic and are derived from radial glial cells during embryogenesis. J Neurosci. 2005;25:10–18. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1108-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ridley AJ, Hall A. The small GTP-binding protein rho regulates the assembly of focal adhesions and actin stress fibers in response to growth factors. Cell. 1992;70:389–399. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Leeuwen FN, Olivo C, Grivell S, Giepmans BN, Collard JG, Moolenaar WH. Rac activation by lysophosphatidic acid LPA1 receptors through the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Tiam1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:400–406. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210151200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heep A, Stoffel-Wagner B, Bartmann P, Benseler S, Schaller C, Groneck P, Obladen M, Felderhoff-Mueser U. Vascular endothelial growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta1 are highly expressed in the cerebrospinal fluid of premature infants with posthemorrhagic hydrocephalus. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:768–774. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000141524.32142.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cherian S, Thoresen M, Silver IA, Whitelaw A, Love S. Transforming growth factor-betas in a rat model of neonatal posthaemorrhagic hydrocephalus. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2004;30:585–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2004.00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ishii I, Contos JJ, Fukushima N, Chun J. Functional comparisons of the lysophosphatidic acid receptors, LP(A1)/VZG-1/EDG-2, LP(A2)/EDG-4, and LP(A3)/EDG-7 in neuronal cell lines using a retrovirus expression system. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:895–902. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.5.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohta H, Sato K, Murata N, Damirin A, Malchinkhuu E, Kon J, Kimura T, Tobo M, Yamazaki Y, Watanabe T, Yagi M, Sato M, Suzuki R, Murooka H, Sakai T, Nishitoba T, Im DS, Nochi H, Tamoto K, Tomura H, Okajima F. Ki16425, a subtype-selective antagonist for EDG-family lysophosphatidic acid receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:994–1005. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.4.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGiffert C, Contos JJ, Friedman B, Chun J. Embryonic brain expression analysis of lysophospholipid receptor genes suggests roles for s1p(1) in neurogenesis and s1p(1–3) in angiogenesis. FEBS Lett. 2002;531:103–108. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dubin AE, Herr DR, Chun J. Diversity of lysophosphatidic acid receptor-mediated intracellular calcium signaling in early cortical neurogenesis. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7300–7309. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6151-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jourquin J, Yang N, Kam Y, Guess C, Quaranta V. Dispersal of epithelial cancer cell colonies by lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) J Cell Physiol. 2006;206:337–346. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fukushima N, Morita Y. Actomyosin-dependent microtubule rearrangement in lysophosphatidic acid-induced neurite remodeling of young cortical neurons. Brain Res. 2006;1094:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ibanez-Tallon I, Pagenstecher A, Fliegauf M, Olbrich H, Kispert A, Ketelsen UP, North A, Heintz N, Omran H. Dysfunction of axonemal dynein heavy chain Mdnah5 inhibits ependymal flow and reveals a novel mechanism for hydrocephalus formation. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:2133–2141. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyan JA, Zendah M, Mashayekhi F, Owen-Lynch PJ. Cerebrospinal fluid supports viability and proliferation of cortical cells in vitro, mirroring in vivo development. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res. 2006;3:2. doi: 10.1186/1743-8454-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gato A, Desmond ME. Why the embryo still matters: CSF and the neuroepithelium as interdependent regulators of embryonic brain growth, morphogenesis and histiogenesis. Dev Biol. 2009;327:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Owen-Lynch PJ, Draper CE, Mashayekhi F, Bannister CM, Miyan JA. Defective cell cycle control underlies abnormal cortical development in the hydrocephalic Texas rat. Brain. 2003;126:623–631. doi: 10.1093/brain/awg058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Humphreys P, Muzumdar DP, Sly LE, Michaud J. Focal cerebral mantle disruption in fetal hydrocephalus. Pediatr Neurol. 2007;36:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stubbs D, DeProto J, Nie K, Englund C, Mahmud I, Hevner R, Molnar Z. Neurovascular congruence during cerebral cortical development. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(Suppl 1):i32–41. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wikoff WR, Pendyala G, Siuzdak G, Fox HS. Metabolomic analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid reveals changes in phospholipase expression in the CNS of SIV-infected macaques. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2661–2669. doi: 10.1172/JCI34138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baumforth KR, Flavell JR, Reynolds GM, Davies G, Pettit TR, Wei W, Morgan S, Stankovic T, Kishi Y, Arai H, Nowakova M, Pratt G, Aoki J, Wakelam MJ, Young LS, Murray PG. Induction of autotaxin by the Epstein-Barr virus promotes the growth and survival of Hodgkin lymphoma cells. Blood. 2005;106:2138–2146. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kishi Y, Okudaira S, Tanaka M, Hama K, Shida D, Kitayama J, Yamori T, Aoki J, Fujimaki T, Arai H. Autotaxin is overexpressed in glioblastoma multiforme and contributes to cell motility of glioblastoma by converting lysophosphatidylcholine to lysophosphatidic acid. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17492–17500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601803200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vukojevic M, Soldo I, Granic D. Risk factors associated with cerebral palsy in newborns. Coll Antropol. 2009;33(Suppl 2):199–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hultman CM, Sparen P, Takei N, Murray RM, Cnattingius S. Prenatal and perinatal risk factors for schizophrenia, affective psychosis, and reactive psychosis of early onset: case-control study. BMJ. 1999;318:421–426. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7181.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kolevzon A, Gross R, Reichenberg A. Prenatal and perinatal risk factors for autism: a review and integration of findings. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:326–333. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.4.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rehen SK, Kingsbury MA, Almeida BS, Herr DR, Peterson S, Chun J. A new method of embryonic culture for assessing global changes in brain organization. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;158:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matyash V, Liebisch G, Kurzchalia TV, Shevchenko A, Schwudke D. Lipid extraction by methyl-tert-butyl ether for high-throughput lipidomics. J Lipid Res. 2008;49:1137–1146. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D700041-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Serum and plasma but not RBCs produce LPA receptor dependent cortical wall disruption.

Fig. S2. Experimental parameters of LPA cortical exposure model.

Fig. S3. Lack of fronto-occipital changes and survival curve of LPA injected animals that develop hydrocephalus over time.

Fig. S4. Bilaterally increased ventricular area and mitotic displacement following LPA exposure.

Fig. S5. LPA exposure induces the formation of denuded cell clusters that originate from the ventricular zone of the developing cortex.

Fig. S6. LPA induces RhoA and Rac1 activation.

Fig. S7. Expression of Lpar1 in the developing embryonic brain at E13.5.

Fig. S8. Expression of Lpar2 in the developing embryonic brain at E13.5.

Fig. S9. LPA-induced cortical disruption and mitotic displacement are abrogated in double-null mutant mice.

Table S1. Histological features associated with hydrocephalus are abrogated in LPA1 and LPA2 double-null animals.

Table S2. Average ± s.d., n, and P-values of data graphed in Figs. 1, 4, and 5.

Video S1: Ciliated ependymal cells are maintained at the apical ventricular surface after vehicle exposure.

Video S2: Ciliated ependymal cells are lost in a patchy fashion at the apical ventricular surface after LPA exposure.