Abstract

Purpose/Objectives

To describe processes for fostering community engagement among Haitian women to facilitate breast health education and outreach that are consonant with Haitians’ cultural values, literacy, and linguistic skills.

Data Sources

Existing breast cancer education and outreach efforts for Haitian immigrant communities were reviewed. Local community partners were the primary source of information and guided efforts to create a series of health-promoting activities. The resultant partnership continues to be linked to a larger communitywide effort to reduce cancer disparities led by the Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network.

Data Synthesis

A systematic framework known as the CLEAN (Culture, Literacy, Education, Assessment, and Networking) Look Checklist guided efforts for improved communications.

Conclusions

Community engagement forms the foundation for the development and adaptation of sustainable breast education and outreach. Understanding and considering aspects of Haitian culture are important to the provision of competent and meaningful care.

Implications for Nursing

Nurses should expand their skills, knowledge, and competencies to better address the changing demographics of their communities. Nurses also can play a critical role in the development of outreach programs that are relevant to the culture and literacy of Haitian women by forming mutually beneficial partnerships that can decrease health disparities in communities.

Cancer is a significant part of the national dialogue on health disparities and is a priority for Healthy People 2010 (Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006). The ultimate causes of cancer disparities are not well understood but likely arise from a complex interplay of factors that impede awareness about screening and limit access to preventive and follow-up care; such factors include, but are not limited to, low socioeconomic status, culture, education level achieved, literacy, social injustice, and poverty (Albano et al., 2007; Braveman & Gruskin, 2003; Chu, Miller, & Springfield, 2007; Singh, Miller, Hankey, & Edwards, 2003). The factors affect access to care and cancer survival and yield an uneven distribution of cancer morbidity and mortality that substantially affects marginalized and disadvantaged populations (Brookfield, Cheung, Lucci, Fleming, & Koniaris, 2009). For example, African American women are disproportionately burdened with poor breast and gynecologic cancer outcomes, often as a result of late-stage diagnoses (Tammemagi, 2007). As a result, identifying special populations that suffer a heavy burden of cancer, determining the causes, and applying relevant interventions to eliminate the disparities are critical (Freeman, 2004).

Immigrants living in the United States are a special population that is impacted heavily by health disparities. International-born status has many implications for women regarding healthcare access, including breast and cervical cancer screening (Goel et al., 2003). For example, immigrant women from ethnically diverse populations tend to have lower incidence but higher mortality from breast cancer; reasons most often cited for this disparity are structural in nature (e.g., late presentation because of limited access to care, healthcare navigation miscommunications, low English proficiency, citizenship status, economic marginalization, social conditions that arise from a combination of these factors) (Andrulis & Brach, 2007; de Alba, Hubbell, McMullin, Sweningson, & Saitz, 2005; Echeverria & Carrasquillo, 2006; Seeff & McKenna, 2003). In addition, immigrant women often experience more breast and cervical cancer and mortality than women born in the United States because of a lack of preventive care access in their countries of origin (Kramer, Ivey, & Ying, 1999; Lewis, 2004) and belief systems incongruent with preventive screening behaviors (Consedine, Magai, Spiller, Neugut, & Conway, 2004; McMullin, De Alba, Chavez, & Hubbell, 2005; Suh, 2008). In general, cancer education and outreach in Haitian communities in the United States has been met with difficulties because of Haitian immigrants’ fatalistic orientations toward cancer (Consedine, Magai, & Neugut, 2004; David, 2001). Such orientations are understandable given the lived realities and context of experience that immigrant women may draw upon for reference. A recent study that assessed colorectal cancer knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among Haitian adults indicated many misperceptions about cancer; however, focus group participants displayed a willingness to follow physicians’ advice (Francois, Elysée, Shah, & Gany, 2008).

Cities in Florida contain large and growing Haitian communities that contribute to the rich diversity of the region. An examination of the health profile of the country of origin and an understanding of health beliefs, practices, and structural constraints in the social context of immigration are key concepts to inform thinking about the potential gravity of a health issue and how best to approach intervention design. The elements suggest a need for an interdisciplinary team of healthcare providers, community partners, and academic researchers to address social, cultural, political, clinical, and public health aspects that combine to affect the disease process in immigrant populations.

This article describes the process of linking national directives to local needs through community partnerships and engagement using effective health education and outreach strategies in the Haitian community in Tampa, FL. Most women participants in the outreach and education programs were Haitian immigrants, as opposed to women of Haitian ethnicity born in the Unites States. The use of a systematic model for designing audience-appropriate cancer communications is presented. The five-pronged approach illustrates the importance of various factors that contribute to successful interventions in community outreach programs. The example provided in this article is specific to breast cancer education but can be applied to other subject matter across the spectrum of cancer care.

Bridging National Directives to Local Efforts

National efforts to reduce cancer disparities through the implementation of local-level programs that can reach medically underserved, socially marginalized communities are in development. Cancer education outreach in the local Haitian community is part of broad community education and outreach at Moffitt and is integral to the Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network (TBCCN). TBCCN is one of 25 community network programs in the country funded by the National Cancer Institute’s Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities. All community network programs are charged with reducing cancer disparities by partnering with community-based organizations, local health departments, faith-based groups, adult literacy centers, and other such agencies to design, implement, and evaluate community-based cancer education interventions and screenings. Because Florida has a sizeable and growing Haitian immigrant community, outreach to the local Haitian community is a foci of TBCCN.

Interventions aimed to reduce cancer or health disparities in Haitian immigrant communities must include an examination of the intersection of culture, literacy, language proficiency, preferred learning modalities, and the sociopolitical context of immigrant status. Intervention design must be guided by the context of community members’ lived realities, which is best understood by soliciting community advice to guide health promotion efforts (Meade, Menard, Martinez, & Calvo, 2007). In addition, a participatory approach that emphasizes community input and involvement at all phases of an intervention provides the groundwork for sustainable interventions and encourages community involvement, engagement, and ownership of health programs, particularly in cross-cultural contexts (Minkler, 2000; Wallerstein & Bernstein, 1994). Therefore, interventions must be congruent with culturally mediated definitions of healthiness and the social realities of what puts a community at risk.

Background, Setting, and Intervention

The systematic model used in the current study is the CLEAN (Culture, Literacy, Education, Assessment, and Networking) Look Checklist (Meade et al., 2007), a useful mnemonic tool that guides the inclusion of elements critical to health education on intervention efforts. The model is applicable at the community outreach level, as well as to that of a clinical-encounter opportunity for patient education. In the context of cancer education, communications with patients and community members alike are considerably improved when these elements are incorporated. Table 1 shows the CLEAN model elements and key questions when incorporating them into health education (for an expanded discussion, see www.moffitt.org/CCJRoot/v14n1/pdf/70.pdf). To use the checklist, nurses should ask themselves some of the key questions to begin the process of gaining population insights and understanding. The steps do not need to occur sequentially, but the order should represent a careful deliberation on how the elements can be applied collectively to bolster community health-promoting efforts. Using the CLEAN model, the current study presents several examples of program and material adaptation to fit the sociocultural context and linguistic and literacy needs and preferences of Haitian immigrant and Haitian American women regarding breast cancer education.

Table 1.

CLEAN Model Elements Applied to Health Education

| Element | Questions to Consider |

|---|---|

| Culture |

|

| Literacy |

|

| Education |

|

| Assessment |

|

| Networking |

|

Note. Based on information from Meade et al., 2007.

Culture: Incorporation of Social Norms and Beliefs

Understandings of health and illness are linked inextri cably to culture, which provides a cognitive framework for comprehending disease and guiding health-seeking behaviors. Illness beliefs often are patterned in ways that reflect historical and geographic influences. Culturally mediated illness beliefs usually are not shed upon immi gration to a new country, as seen in the pluralistic medi cal system in Haitian culture. The system is comprised of ethnomedical and biomedical elements; for example, cultural beliefs about illness causality include distinctions between supernatural and natural illnesses. Supernatural illnesses may be perceived to be caused by familial spirits or as the manifestation of ill will sent by a jealous neighbor or other known person through the use of a traditional Voodoo practitioner (e.g., houngan, manbo) (Brodwin, 1996). Concepts relevant to Voodoo beliefs and practices may be important considerations because these beliefs can shape attitudes and compliance with treatment (Des rosiers & St. Fleurose, 2002). Classic ethnographic data indicate that natural illnesses often are attributed to bodily imbalance, particularly of hot and cold, as influenced by humoral theory, which posits that an imbalance of bodily constitutional humors (fluids) results in illness (Foster, 1993; Laguerre, 1981). Within this orientation, certain ill nesses have corresponding hot or cold remedies, such as avoidance of foods or climates with the same properties while ill (Laguerre, 1987; Miller, 2000).

In addition to the etiologic beliefs, a great importance is placed on blood, including its movement and direc tionality in the body, quality, quantity, and temperature (Laguerre, 1987; Miller, 2000). Blood equilibrium in those aspects is central to good health. Balance is maintained through the observance of external sources, including environmental temperatures, certain foods, or emotional extremes, which could influence blood stability. In addition, home remedies often are used for maintaining health and for affecting cures, particularly for less serious illnesses (Miller). Home remedies primarily consist of teas and poultices made from medicinal plants. The authors observed that the plants often are grown in women’s yards and cultivated for health purposes. Home remedies also may consist of over-the-counter medicines and balms. Importantly, using home remedies as a first resort is a common practice in Haitian culture. Therefore, clinical practitioners and educators should inquire about the use of home remedies when asking what “other” medicines Haitian women are taking (Laguerre, 1984).

Haitian women’s understanding of breast cancer is informed by experience (e.g., personal, knowledge of others’ experiences and outcomes) and culturally mediated beliefs about disease causality and course. Women’s comments and questions to the community health worker during cancer education outreach events reflected themes that incorporated mixed elements of ethnomedical and biomedical models of illness causality for breast cancer. For example, cancer most often is perceived as fatal because of cultural beliefs and structural realities. A woman stated, “I’ve never seen anyone who gets surgery on her breast come out alive.” Others said, “X-ray while having a mammogram can cause cancer,” and, “Cancer is a sent sickness; it is not a natural disease.” The women’s questions and comments revealed perceptions that breast cancer could be caused by previous injury to the breast (physical trauma); the result of a past transgression, manifesting as some form of moral retribution; or a condition “sent” upon them by someone intending to do harm through supernatural means. The beliefs were addressed openly but sensitively by the Haitian clinicians who took part in the intervention programs and were aware of the influence of culture on etiologic beliefs. The expressed beliefs also were consonant with findings from researchers working with Haitian immigrant communities elsewhere in the United States (Consedine, Magai, & Neugut, 2004; Consedine, Magai, Spiller, et al., 2004; David et al., 2005). In addition, overall time spent in the United States interacted with greater breast cancer screening usage, particularly among Haitians (Brown, Consedine, & Magai, 2006). The results have implications for health-promoting behaviors and suggest a need to expand outreach strategies to Haitian women, particularly recent immigrants, who represent a vulnerable group at risk for breast cancer.

Many women generally do not distinguish one form of cancer from another, or cancer by site, which is a critical point for outreach and education given the success rates of treatment for cervical cancer with early detection and improved survival for breast cancer with early detection and treatment. To illustrate, questions such as, “Can a person get breast cancer in the leg?” and, “Is cancer contagious?” were asked of the community outreach worker when delivering education sessions. The examples demonstrate a need for educators to be aware of cultural beliefs as well as how people understand cancer as a disease in general. Educators should operate from this worldview to open effective health communications.

Literacy and Education: Meeting Community-Directed Needs

Attention to cross-cultural literacy in the context of health is critical for creating acceptable, relevant materials that resonate with the intended population (Ramirez, 2003; Simon, 2006). For many immigrant communities, literacy and language are closely linked and may contribute to newcomers’ social isolation (Zanchetta & Poureslami, 2006). Language needs in the Haitian immigrant community present somewhat unique challenges for health educators seeking to create relevant education materials. First, the education levels of Haitian immigrants may vary widely. The 2003 estimated literacy rate in Haiti (i.e., the percentage who can read and write) is 53% for the total population and slightly less for women (U.S. Central Intelligence Agency, 2007). French is the language of the government and education system in Haiti; however, Haitian Creole (Kreyol) is spoken by everyone. Spoken and written French fluency generally is reserved for those with more education, and knowledge of and ability to speak French is an important indicator of social status (Zéphir, 1997). Creole is largely a spoken language and far fewer people read in Creole than speak it. In addition, access to formal education in the United States for disenfranchised immigrants and access to English language courses given outside of the demands of work hours, family obligations, and transportation to course sites is problematic. Together, the factors give rise to a situation in which printed materials, even when provided in Creole, may be unusable.

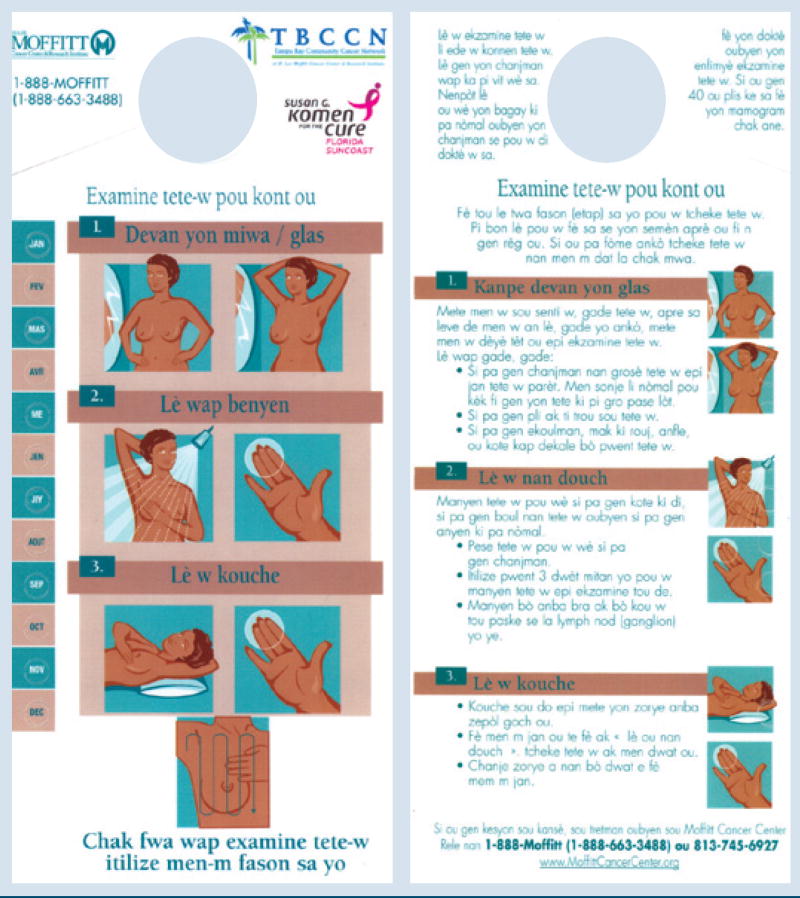

As a result, the authors worked with Haitian community partners to create a breast self-examination shower card with monthly reminders and combined pictorial and written instructions in Haitian Creole on how to perform a self-examination (to view the Haitian Creole shower card, see Appendix A in the online version of this article at http://ons.metapress.com/content/0190-535X). The material is used with oral education provided by a bilingual outreach educator to explain specific points and information about screening guidelines. The educational tool is disseminated at health events, mobile mammography screenings, and yearly festivals, such as the annual Haitian Heritage Celebration. The community partners have expressed a desire for more audiovisual cancer communications in Creole. The modality could help solve the written language dilemma. Future project plans include the development of a Creole language breast and cervical health DVD to benefit local Haitian women.

Assessment: Meeting Community Health Needs

For educational interventions to affect cancer disparities beyond knowledge and informational needs, access to preventive care and follow-up services is essential. The broader health needs of the community and where they locate cancer-related health concerns also should be recognized. Partners described other chronic disease concerns of the community, primarily high blood pressure and diabetes, as well as a general lack of awareness about resources available for medically underserved people, regardless of ability to pay or immigration status. As a result, the authors incorporated other health information and screenings (e.g., blood sugar, cholesterol, blood pressure) into cancer education events to meet community-defined needs. The authors also provided information about local Federally Qualified Health Centers’ state-specific programs for families and children, local resources for literacy and English proficiency instruction, and how to access those services.

Additional assessment included identifying complementary ways to promote cancer education awareness and conduct effective educational outreach for breast and cervical cancer. In recognition of the high degree of religiousness in primarily Christian denominations observed in the Haitian community, the authors proposed adapting and implementing the Witness Project®, a faith-based breast and cervical cancer education program originally developed for African American women (Erwin, Spatz, & Turturro, 1992), with the Haitian women in our community. The evidence-based program focuses on the delivery of culturally appropriate breast-cancer education messages in ways that are consonant with learning preferences, cultural norms, and communication styles in acceptable venues, including church-based facilities and community centers. The messages are designed to influence women’s participation in early detection practices and screenings, including breast self-examinations, clinical breast examinations, mammography as indicated, and Pap testing (Erwin et al., 2003).

While taking care not to impose the culturally salient intervention model for African American women onto a different ethnic group, the possibility of adapting and implementing the program in a Haitian faith-based setting was explored with members of a Haitian women’s church organization. Women from the group noted that health programs were welcomed and needed to benefit local women, even though cancer was a topic that elicited many disparate beliefs about disease causality and incited fear. The women’s church group worked diligently with the outreach team to deliver a successful program customized to the language and linguistic needs of Haitian women. Program information was announced after church services and through key community contacts using word of mouth as well as e-mail announcements. The social networks of the community partners were critical to ensure that the information reached women in the community in a timely way.

In the traditional format of a Witness Project® program, breast cancer survivors served as role models who told their stories about their experience (i.e., witnessed) and promoted early detection. Initially, several African American women involved in the existing Witness Project® shared their cancer journey with the aid of a Creole translator. The women were regarded highly for sharing their stories. Next, the program was enhanced by using Haitian healthcare professionals. Knowing that doctors and nurses are respected highly and regarded as trusted spokespersons in the Haitian community, the authors asked local Haitian clinicians to become part of the program. The clinicians provided critical support for addressing clinical questions from participants and reiterating important health education points. For example, a physician worked with the community’s high religiosity by stating that going to church does not grant immunity from disease and women must take care of their health the same way that they do their souls.

Networking: Creating Linkages and Navigating Through Systems

Collaborations formed after a period of time spent establishing rapport and developing relationships with community stakeholders. Community members were enthusiastic about having breast and cervical cancer outreach efforts personalized to the specific needs of local Haitian immigrant women and learning of critical linkages to services such as screening mammography. In addition, the authors linked cancer education and awareness efforts with the accessibility of mammography for women aged 40 years or older whose income qualified and facilitated referrals for younger women who had a family history of breast cancer. Meeting the critical access need was a significant element that contributed to the ongoing success of outreach in the Haitian community because most Haitian women served are under- or uninsured. Women with abnormal mammograms are navigated to care within the authors’ cancer center; as a result, the authors are able to connect the current and subsequent outreach education efforts with focused screening and navigation.

Results

From the program’s inception in 2005, thousands of people have been outreached with culturally appropriate cancer education and information through community outreach efforts. In addition, hundreds of women have received mammograms. The cancer center’s partnership with the Haitian community has grown, and TBCCN and the cancer center’s outreach program have fueled additional development of cancer educational materials in Creole; cosponsored an annual cultural, educational, and health fair event; and leveraged funding from other sources for cancer education for the Haitian community. The authors have used the CLEAN checklist to create a plain language Creole shower card and adapt a program that matches the high religiosity of the community. As stated by Meade and Calvo (2001), effective community partnerships for health education and outreach include a framework based on a network of partners with common goals; communication processes based on trust; and bilingual, bicultural, and culturally competent staff. The approach situates cultural competence and proficiency in close alignment with community-centered nursing care (Engebretson, Mahoney, & Carlson, 2008).

Discussion and Conclusions

When developing cancer outreach programs, one must layer additional levels of understanding and sensitivity to the social, cultural, and political conditions of community members’ home countries; language and literacy needs; basic healthcare access obstacles; cultural significance of gender and age roles; culturally mediated etiologic perceptions of disease; and illness experiences, religiosity, and the sociopolitical nature of immigration situations. All of the factors affect health communication, education, and general health status. Partnerships with community-based organizations, participation from community gatekeepers (e.g., respected physicians), and support from clergy are key elements to outreach success for a marginalized community. Nurses should become engaged in their community and include community members in the process—from planning to implementation to evaluation—to ensure program effectiveness and sustainability.

Implications for Nursing

Nurses are in an ideal position to combine their skills, knowledge, and resources to affect the health and well-being of diverse community members, to establish relationships with key community members, and to promote trust and commitment within the community. This nursing position, with a sincere demonstration of respect for cultural beliefs that influence health behaviors of community members, is crucial to achieving positive outcomes. Working within the cultural belief frameworks and incorporating those beliefs into educational messages is critical. In addition, the nurse as a health educator facilitates the development of effective strategies in consideration of literacy levels and cultural norms that support community members in acting on cancer prevention messages (Miller, 2000). Therefore, nurses should be engaged with community leaders and become immersed in their communities to gain an understanding of the health beliefs, backgrounds, and language needs of the groups that they are trying to reach with their interventions. Keeping an open and inquiring attitude will increase the possibilities of gaining new understanding of the groups served. Nurses also should examine the utility of the components of the CLEAN Model Checklist for enhancing their educational encounters and communications. In this manner, cancer outreach programs can better echo the realities of people’s everyday lives, reduce cancer health disparities, and contribute to improved health and well-being.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge key collaborators and partners in the community: Haitian American Alliance, Inc., Haitian Organization for Population Activities and Education, Inc., Pastor and Sister Thésée of Eglise Baptiste Haïtienne, and Group Fanm of Our Lady of Perpetual Help Catholic Church in Tampa.

This project was supported, in part, by the National Cancer Institute (Grant No. U01 CA114627). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities. The project also was supported by the Susan G. Komen for the Cure, Suncoast Affiliate, Tampa, FL. Meade can be reached at cathy.meade@moffitt.org, with copy to editor at ONFEditor@ons.org.

Appendix A. Breast Self-Examination Shower Card in Haitian Creole

Note. Image courtesy of H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute, Inc. Used with permission.

Contributor Information

Cathy D. Meade, Department of Oncologic Sciences in the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control at H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute in Tampa, FL, and an adjunct faculty in the College of Nursing at the University of South Florida in Tampa.

Janelle Menard, Division of Cancer Prevention and Control at Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center in Miami, FL.

Claudine Thervil, Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute.

Marlene Rivera, Tampa Bay Community Cancer Network, H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center and Research Institute.

References

- Albano JD, Ward E, Jemal A, Anderson R, Cokkinides VE, Murray T, et al. Cancer mortality in the United States by education level and race. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2007;99(18):1384–1394. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrulis DP, Brach C. Integrating literacy, culture, and language to improve health care quality for diverse populations. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2007;31(1, Suppl):S122–S133. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2007.31.supp.S122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braveman P, Gruskin S. Defining equity in health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57(4):254–258. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.4.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodwin PE. Medicine and morality in Haiti: The contest for healing power. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Brookfield KF, Cheung MC, Lucci J, Fleming LE, Koniaris LG. Disparities in survival among women with invasive cervical cancer: A problem of access to care. Cancer. 2009;115(1):166–178. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WM, Consedine NS, Magai C. Time spent in the United States and breast cancer screening behaviors among ethnically diverse immigrant women: Evidence for acculturation? Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2006;8(4):347–358. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9005-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu KC, Miller BA, Springfield SA. Measures of racial/ethnic health disparities in cancer mortality rates and the influence of socioeconomic status. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2007;99(10):1092–1100. 1102–1104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consedine NS, Magai C, Neugut AI. The contribution of emotional characteristics to breast cancer screening among women from six ethnic groups. Preventive Medicine. 2004;38(1):64–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consedine NS, Magai C, Spiller R, Neugut AI, Conway F. Breast cancer knowledge and beliefs in subpopulations of African American and Caribbean women. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2004;28(3):260–271. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.28.3.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David M. Communication, cultural models of breast cancer beliefs, and screening mammography: An assessment of attitudes among Haitian immigrant women in eastern Massachusetts. Boston: Boston Medical Center; 2001. (Rep. No. A226683) [Google Scholar]

- David MM, Ko L, Prudent N, Green EH, Posner MA, Freund KM. Mammography use. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97(2):253–261. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Alba I, Hubbell FA, McMullin JM, Sweningson JM, Saitz R. Impact of U.S. citizenship status on cancer screening among immigrant women. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2005;20(3):290–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers A, St Fleurose S. Treating Haitian patients: Key cultural aspects. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 2002;56(4):508–521. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2002.56.4.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echeverria SE, Carrasquillo O. The roles of citizenship status, acculturation, and health insurance in breast and cervical cancer screening among immigrant women. Medical Care. 2006;44(8):788–792. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000215863.24214.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engebretson J, Mahoney J, Carlson ED. Cultural competence in the era of evidence-based practice. Journal of Professional Nursing. 2008;24(3):172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin DO, Spatz TS, Turturro CL. Development of an African American role model intervention to increase breast self-examination and mammography. Journal of Cancer Education. 1992;7(4):311–319. doi: 10.1080/08858199209528188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster GM. Hippocrates’ Latin American legacy: Humoral medicine in the New World. New York: Gordon and Breach; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Francois F, Elysée G, Shah S, Gany F. Colon cancer knowledge and attitudes in an immigrant Haitian community. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2008;11(4):319–325. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9126-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman H. Poverty, culture, and social injustice: Determinants of cancer disparities. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2004;54(2):72–77. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel MS, Wee CC, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Ngo-Metzger Q, Phillips RS. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer screening: The importance of foreign birth as a barrier to care. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18(12):1028–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2003.20807.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer EJ, Ivey SL, Ying Y. Immigrant women’s health: Problems and solutions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Laguerre MS. Haitian Americans. In: Harwood A, editor. Ethnicity and medical care. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1981. pp. 172–210. [Google Scholar]

- Laguerre MS. American odyssey: Haitians in New York City. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Laguerre MS. Afro-Caribbean folk medicine. South Hadley, MA: Bergin and Garvey; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MJ. A situational analysis of cervical cancer in Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington, DC: Pan American Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- McMullin JM, De Alba I, Chavez LR, Hubbell FA. In-fluence of beliefs about cervical cancer etiology on Pap smear use among Latino immigrants. Ethnicity and Health. 2005;10(1):3–18. doi: 10.1080/1355785052000323001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CD, Calvo A. Developing community-academic partnerships to enhance breast health among rural and Hispanic migrant and seasonal farm worker women. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2001;28(10):1577–1584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CD, Menard JM, Martinez D, Calvo A. Impacting health disparities through community outreach: Utilizing the CLEAN look (culture, literacy, education, assessment, and networking) Cancer Control. 2007;14(1):70–77. doi: 10.1177/107327480701400110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NL. Haitian ethnomedical systems and biomedical practitioners: Directions for clinicians. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2000;11(3):204–211. doi: 10.1177/104365960001100307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M. Using participatory action research to build healthy communities. Public Health Reports. 2000;115(2–3):191–197. doi: 10.1093/phr/115.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez AG. Consumer-provider communication research with special populations. Patient Education and Counseling. 2003;50(1):51–54. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00080-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeff LC, McKenna MT. Cervical cancer mortality among foreign-born women living in the United States, 1985–1996. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 2003;27(3):203–208. doi: 10.1016/s0361-090x(03)00062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon CE. Breast cancer screening: Cultural beliefs and diverse populations. Health and Social Work. 2006;31(1):36–43. doi: 10.1093/hsw/31.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh GK, Miller BA, Hankey BF, Edwards BK. Area socioeconomic variations in U.S. cancer incidence, mortality, stage, treatment, and survival, 1975–1999. 2003. Retrieved September 22, 2009, from http://seer.cancer.gov/publications/ses/contents.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh EE. The sociocultural context of breast cancer screening among Korean immigrant women. Cancer Nursing. 2008;31(4):E1–E10. doi: 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305742.56829.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammemagi CM. Racial/ethnic disparities in breast and gynecologic cancer treatment and outcomes. Current Opinions in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;19(1):31–36. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3280117cf8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. CIA world factbook: Haiti. 2007. Retrieved March 18, 2007, from https://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/ha.html.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. 2006. Retrieved December 9, 2006, from http://www.healthypeople.gov/default.htm.

- Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Introduction to community empowerment, participatory education, and health. Health Education Quarterly. 1994;21(2):141–148. doi: 10.1177/109019819402100202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanchetta MS, Poureslami IM. Health literacy within the reality of immigrants’ culture and language. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2006;97(2, Suppl):S26–S30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zéphir F. The social value of French for bilingual Haitian immigrants. French Review. 1997;70(3):395–406. [Google Scholar]