Abstract

Objective

To describe self-reported health status and quality of life (QOL) of ambulatory youths with cerebral palsy (CP) compared with sex- and age-matched typically developing youth (TDY).

Design

Prospective cross-sectional cohort comparison.

Setting

Community-based.

Participants

A convenience sample of 81 youth with CP (age range, 10–13y) with Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) levels I through III and 30 TDY participated. They were recruited from 2 regional children’s hospitals and 1 regional military medical center.

Interventions

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measures

Participants completed the Child Health Questionnaire–Child Form (CHQ-CF87) for health status and the Youth Quality of Life for QOL.

Results

Youth with CP reported significantly lower health status than age- and sex-matched TDY in the following CHQ-CF87 subscales: role/social behavioral physical, bodily pain, physical function, and general health (CP mean rank, 46.8–55.2; TDY mean rank, 62.2–80.9). There were significant differences across GMFCS levels. There were no significant differences in self-reported QOL.

Conclusions

Self-reported health status, but not QOL, appears sensitive to the functional health issues experienced by ambulatory youth with CP. Pain management and psychosocial support may be indicated for them.

Keywords: Cerebral palsy, Health status, Quality of life, Rehabilitation

The types of cerebral palsy (CP) compatible with independent ambulation, hemiplegia, and diplegia, comprise 48% to 79% of all cases.1 All ambulatory persons with CP experience limitations in walking and other physical activities. It is generally believed that people who experience such limitations have less than optimal quality of life (QOL); below normal health-related QOL (HRQOL) in youth with CP has been reported by parents and other surrogate reporters.2,3 Improving QOL for youth with CP is consistent with the major policy goals of Healthy People 2010 for persons with disability and with a recent National Institutes of Health program announcement for the study of QOL issues in persons with limited mobility.4 To date, descriptions of the health status and/or QOL of ambulatory children with CP have primarily been oriented toward functional health skills (ie, walking ability) and have been obtained from reports by parents or other surrogates, rather than by youths’ self-reports of their perceived QOL.

The concept of QOL as an aspect of “health” was first proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO)5 in 1948. Health was defined as not only an absence of illness but also the presence of physical, mental, and social well-being. The current WHO definition of QOL includes a person’s “perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value system in which they live, and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns.”6(p42),7(p1-2) This definition does not include issues related to physical or functional health (ie, walking ability), and suggests that youth themselves (rather than parents) should define and report their own QOL.8

Health status, functional status, well-being, quality of life, and health-related quality of life are terms that are often employed interchangeably in the outcomes literature. There is no clear consensus of definition and/or application. In 2000, Patrick and Chiang9 proposed useful distinctions between health status, QOL, and HRQOL. “Health status” is presented as a unique concept with domains that range from positive aspects of life to the more negatively perceived aspects. For example, within the study of health status, “functional status” measures would relate to limitations in performance of activities agreed to be important for society or to the individual. Numerous measures are labeled QOL or HRQOL in the literature but most items in these measures describe functional status (ie, Child Health Questionnaire [CHQ]).8 Although intuitively it may seem that functional status would be highly associated with QOL, many persons who have activity limitations and/or use wheelchairs report having a high QOL.9

“Quality of life,” as defined by the WHO, is a broader construct than “health status” because it includes aspects of the social and physical environment that may or may not be affected by health or a treatment.6 HRQOL is often applied as an outcome measure that focuses on the aspects of life and activity that are influenced by health conditions or services. Patrick and Chiang9 suggested that “health status” and “health-related quality of life” are most useful in the context of assessment of health services and treatment efficacy, while “quality of life” measures should be used to evaluate environments and/or issues external to the context of health care.

The literature on health and/or QOL in youth with CP has been primarily based on parental report and historically has combined the constructs of “health” with “QOL” in reporting CHQ data as HRQOL. Liptak et al2 described caregiver perceptions of health status with the Child Health Questionnaire–Parent Form (CHQ-PF28) in children with moderate to severe CP. Caregivers perceived those children to have worse general and physical health compared with the CHQ norms. These data, demonstrating that increased severity of CP is associated with lower CHQ scores, support the concept that perceived health status is related to medical conditions. Kennes et al3 reported a strong association of caregiver-reported functional ambulatory health status to level of motor impairment. Perceptions of health status by caregivers of 408 school-aged children were inversely correlated with walking impairment. CHQ data for a sample of ambulatory Australian youth with CP documented parental reported health status to be lower than a normative sample.10 Vargus-Adams11 also documented a direct negative correlation with parental reported CHQ physical function with Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) level. Ambulation skill was negatively associated to a lesser degree with the general health and role–physical CHQ subscales.

Varni et al12 recently documented child self-report HRQOL with the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL). The healthy normative sample reported higher HRQOL than youth with CP. In a cross-sectional study of 90 youth with CP, ages 7 to 13 years, Pirpiris et al,13 using the parental-report PedsQL and the Pediatric Outcomes Data Collection Instrument (PODCI), also documented lower HRQOL compared with normative samples.

Self-reported life experiences for youth with CP based on the current WHO definition of QOL, separate from health status or HRQOL, have not been documented. In this cross-sectional study, our aim was to investigate health status unique from QOL of youth with CP (appendix 1) compared with an age- and sex-matched group of typically developing youth (TDY). This comparison group controls for cultural factors (home, school environment) that may influence self-report of health status and/or QOL. We selected the matched comparison group rather than simply using an existing “normative” sample in order to better control for social and environmental factors that are important in the WHO definition of QOL. This investigation was conducted as part of a larger descriptive study of the relation between physical activity and health status and QOL in youth with CP.14,15 The a priori hypothesis was that self-reported health status and QOL would be ordered by activity capacity and functional level, as measured by the GMFCS, such that TDY would be greater than level I, level I greater than level II, and level II greater than level III.16

METHODS

Participants

Criteria for inclusion for the youth with CP were: GMFCS levels I through III, ages 10 to 13 years, and ability to read and understand at the 10-year age level as confirmed by the Wide Range Achievement Test 3 (WRAT3) reading subtest.17 Inclusion criteria for the TDY were: age 10 to 13 years, matched sex of a participant with CP and at least a 10-year age reading level. Subjects were excluded if they had orthopedic or neurologic surgery in the past 12 months, had incurred a fracture, sprain, and/or strain injury of their legs in the past 6 months, or reported having exercise-induced asthma, cardiovascular compromise from a congenital heart defect, and/or a seizure disorder not controlled by medication.

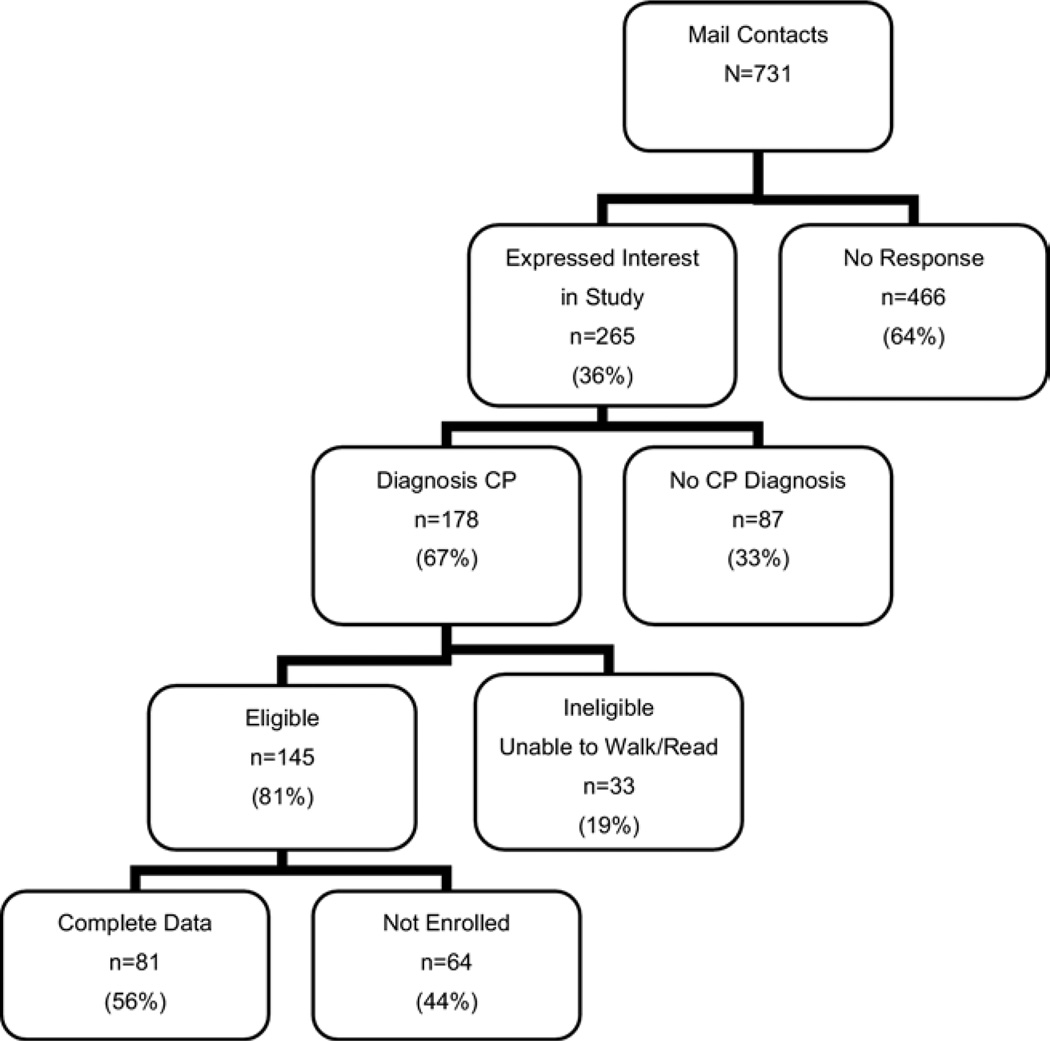

The study sample was recruited using a focused direct mailing to the guardians of ambulatory children with CP who had been seen at 3 children’s hospitals or 1 regional military hospital in the Pacific Northwest, to school-based nurses, and physical and occupational therapists practicing in Washington state. The study sample totaled 111 youth—81 with CP and 30 TDY. Recruitment outcomes are shown in figure 1 for the youth with CP. The comparison cohort sample of TDY was comprised of 15 participants who were siblings of the participants with CP, 5 who were friends of the subjects with CP, and 10 who were the TDY recruited through a postal mailing.

Fig 1.

Recruitment results for participants with CP showing numbers and reasons for exclusions. Adapted from Bjornson et al.14 Reprinted with permission.

Outcome Measures

Participants with CP were categorized by GMFCS levels I to III as a definition of functional status (see appendix 1).16 The GMFCS classifies the motor involvement of children with CP on the basis of their functional sitting and walking abilities and their need for assistive technology and wheeled mobility. Youth in level I are able to climb stairs without upper-extremity assistance, level II require upper-extremity assist to climb stairs, while youth in level III are unable to climb stairs and walk only with an assistive device.

Self-perceived functional health status of the youth participating was measured by the Child Health Questionnaire–Child Form (CHQ-CF87) child version (see appendix 1).18 The CHQ-CF87 is a generic norm-referenced child health status instrument constructed to measure the physical and psychosocial well-being of children 5 years of age and up across 9 subscales of physical, emotional, and behavioral health. The developers of the CHQ report a Cronbach α range of .80 to .94, indicating acceptable internal consistency.

To capture QOL unique from health status, we administered the Youth Quality of Life Instrument–Research Version (YQOL-R) (see appendix 1).8,19 YQOL has documented self-reported QOL in youth with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and across adolescent health risk behaviors.20,21 The YQOL-R assesses 5 domains: total QOL, sense of self, social relationships, culture and community environment, and general QOL. The items are designed to assess the youths’ “position in life” as defined by the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) group.6 Psychometrics on the YQOL-R perceptual scales have yielded acceptable internal consistency (Cronbach α range, .77–.96), reproducibility (intraclass correlation coefficient range, .74–.85), associations with similar concepts (r=.73), and ability to distinguish among groups with disabilities (Cronbach α range, .77–.96).8,19

Demographics included sex, age, and socioeconomic status (SES). The education level of the consenting guardian served as a proxy measure of SES. Because youth in this age range are prone to “good and bad” days in their perception of their lives, a single question was collected to measure this potential confounding factor. “How do you feel about your life today?” was asked as a covariate to measure this variable—“current day outlook.”15 This question was scored on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (terrible) to 7 (delighted) and served as a proxy measure to test for seasonal variation of responses.22

Procedures

All study procedures were approved by the local human subjects institutional review boards (IRBs). Participants completed written informed assent and parents or legal guardians provided written informed consent after initial contact by phone and/or mail per IRB guidelines and approval. The WRAT3 reading subtest was administered to each participant to assure 10-year-old reading level. Participants completed the CHQ-CF87 and then the YQOL-R in a home-based study visit. Data were collected only during the months when school was in session in order to sample school-aged youth during their typical daily lives (September 2004–June 2005 and September 2005–November 2005). Questionnaires were administered by the principal investigator and a trained research assistant. Procedural reliability was maintained (99% agreement) between the principal investigator and research assistant throughout the project.

Statistical Analysis

Comparability of groups (CP vs TDY) was tested using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or chi-square test. A factorial ANOVA controlling for age, sex, SES, and current day outlook tested for mean differences in CHQ and YQOL across GMFCS levels. Current day outlook significantly impacted the variance of the CHQ and YQOL scores, thus we utilized a post hoc Mann-Whitney U test. The Kruskal-Wallis mean ranks tested the CHQ subscales and YQOL domains for differences between youth with CP and TDY due to non-normal distributions. We employed a post hoc Mann-Whitney to test for differences within the GMFCS levels. All analysis was completed with SPSS softwarea with a statistical significance set at the .05 level.

RESULTS

At baseline, no significant differences between the group with CP and TDY were found for any demographic variables (table 1). Participants with CP were 52% boys with a mean age ± standard deviation of 11.8±1.3 years; 77.8% white and 9.9% Hispanic. TDY participants were 50% male with a mean age of 11.9±1.2 years and white (83.3%). GMFCS levels were: level I, 31; level II, 30; and level III, 20. The percentage of parents or legal guardians having some college education was slightly greater for the youth with CP as compared with those of TDY (39.5% vs 26.7%). The mean current day outlook scores for the 2 groups was 5.6 (CP) and 5.8 (TDY), respectively. Age, sex, and SES did not significantly impact the variance of CHQ and YQOL across GMFCS levels. When SES was not controlled for, the outcome of within or between group differences did not change. Current day outlook significantly impacted only the general QOL domain of the YQOL (P<.02), suggesting no seasonal influence on the CHQ subscale and the remaining YQOL domains.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Sample (N = 111)

| Youth Characteristics | Youth With CP |

TDY | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 81 | 30 | NA |

| Mean age (y) | 11.8 ± 1.3 | 11.9 ± 1.2 | .98 |

| Sex (% boys) | 42 (52) | 15 (50) | .86 |

| GMFCS | |||

| Level I | 31 | NA | NA |

| Level II | 30 | NA | NA |

| Level III | 20 | NA | NA |

| Race (%) | |||

| White | 63 (77.8) | 25 (83.3) | .78 |

| Hispanic | 8 (9.9) | 1 (3) | NA |

| Asian | 5 (6.2) | 3 (10) | NA |

| Black | 3 (3.7) | 1 (3) | NA |

| Other | 2 (2.4) | 0 (0) | NA |

| SES of parents/guardians | |||

| % Vocational school/college | 32 ± 39.5 | 8 ± 26.7 | .18 |

| Mean current day outlook | 5.6 ± 1.4 | 5.8 ± 1.2 | .53 |

NOTE. Values are mean ± standard deviation or n (%). Adapted from Bjornson et al.14 Reprinted with permission.

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Level of significance was determined by 1-way ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-square test for categorical variables.

Health Status

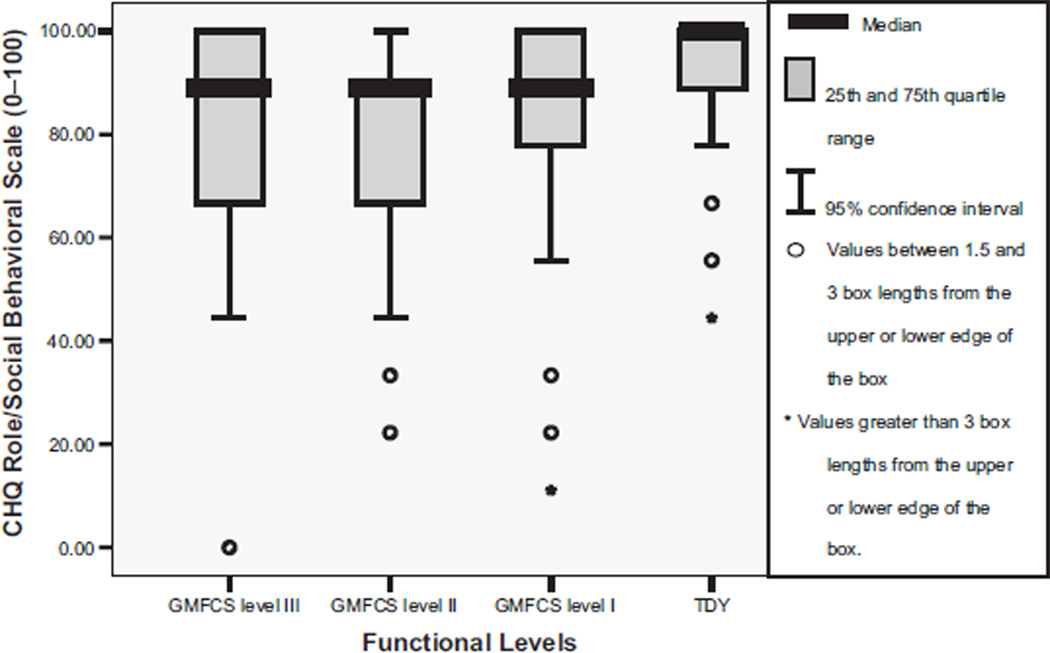

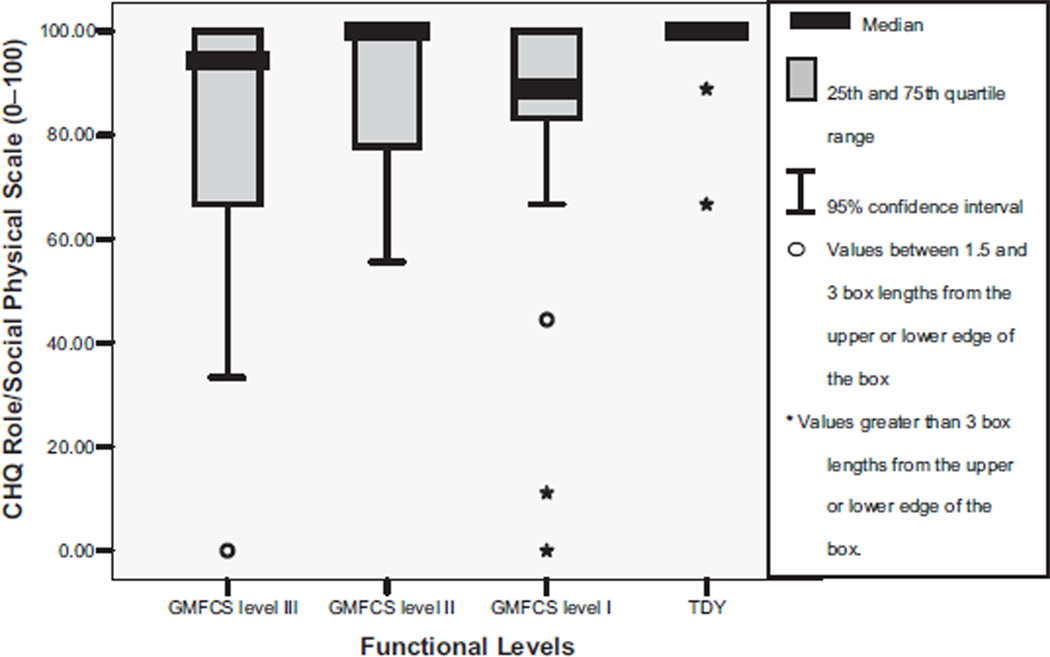

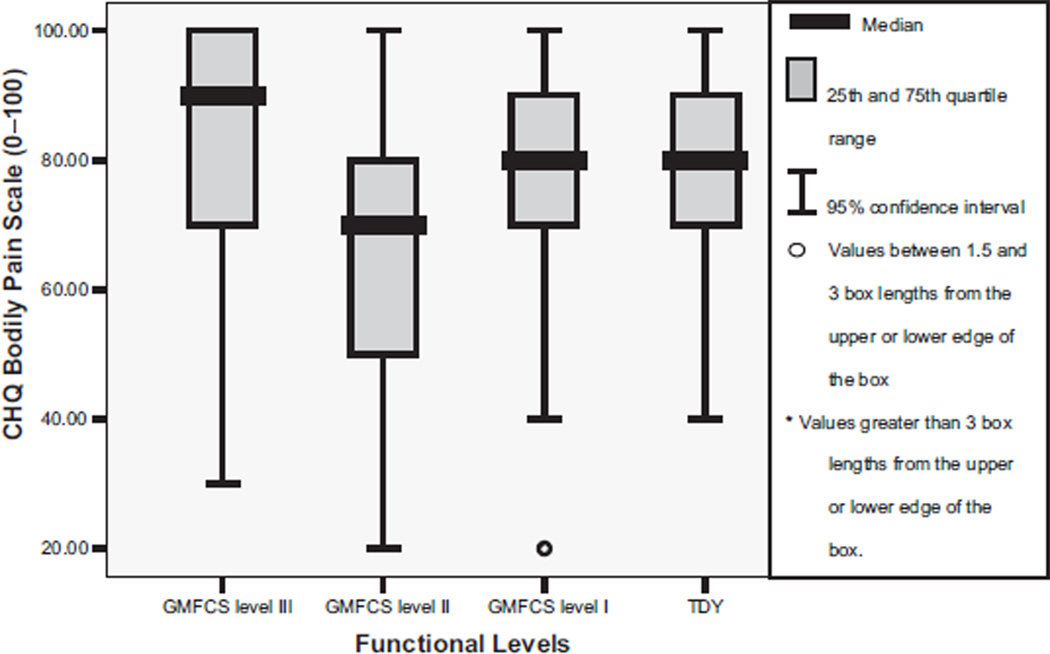

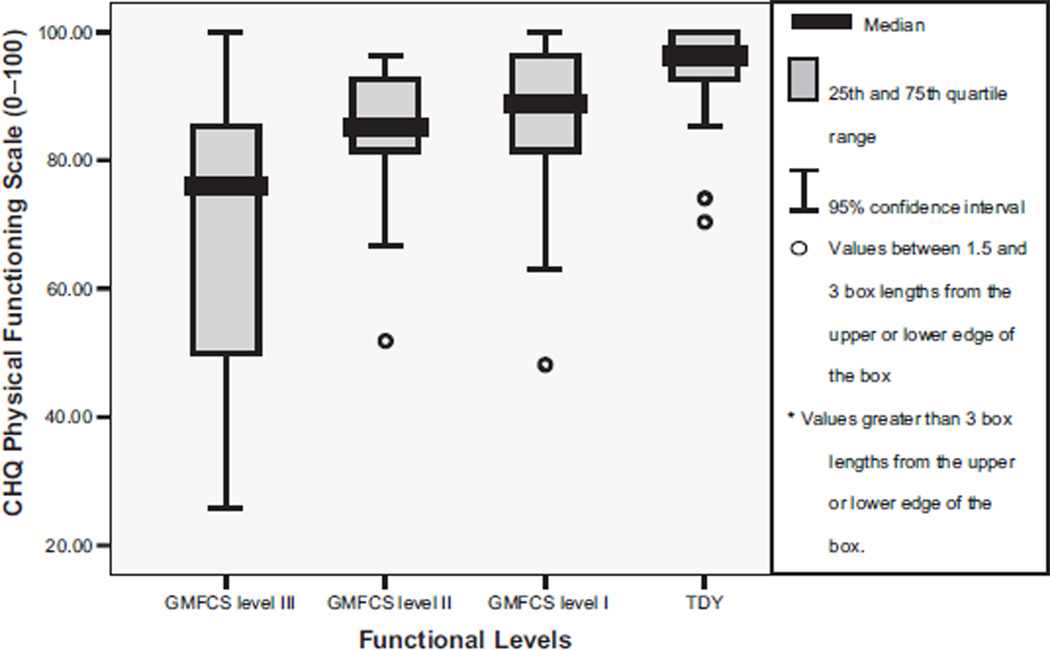

The Cronbach α for the CHQ was .88. Table 2 shows that youth with CP compared with TDY reported significantly different scores on the CHQ subscales of role/social behavioral, role/social physical, bodily pain, physical function, and general health perception (P range, <.001 to .04). Post hoc tests between group differences for the role/social behavioral scale were significant between TDY and level II (fig 2). The role/social physical subscale score was significantly greater for TDY than for the levels I and III (P<.005) youth (fig 3). Bodily pain (fig 4) was reported as higher overall by level II participants with significant between groups differences found for level II compared with TDY. The physical function subscale outcomes were ordered by increasing functional status (fig 5). All between group relationships were significantly different (P range, <.002 to .005) except for between levels I and II (P=.15). General health perception self-report (fig 6) was most varied for youth in level II with significant difference only noted for the TDY compared with levels I and II (P<.001).

Table 2.

Self-Reported Health Status and QOL Comparison of Youth With CP (n = 81) With TDY (n = 30)*

| CHQ-CF87 Subscales† | CP Mean Rank |

TDY Mean Rank |

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical function | 46.8 | 80.9 | <.001 |

| General health perception | 50.3 | 71.3 | .002 |

| Role/social physical | 51.4 | 68.3 | .005 |

| Role/social behavioral | 51.2 | 69.0 | .007 |

| Bodily pain | 55.2 | 62.2 | .04 |

| Self-esteem | 52.8 | 64.6 | .09 |

| Family activities | 53.6 | 62.5 | .19 |

| Role/social emotional | 53.8 | 61.9 | .20 |

| Family cohesion | 54.4 | 60.2 | .38 |

| YQOL domains‡ | |||

| General QOL | 55.7 | 56.9 | .84 |

| Relationships | 55.1 | 58.5 | .61 |

| Environment | 55.0 | 66.0 | .59 |

| Self | 52.3 | 60.9 | .23 |

| Total QOL | 53.7 | 62.2 | .22 |

Results remained the same for analysis where only siblings or nonsiblings as the TDY comparison group.

Physical function measures presence and extent of physical limitations due to health-related problems in areas of self-care, mobility, and activities of varying strenuousness (walk vs run). General health is the subjective assessment of overall health and illness in past, future, and current as well as susceptibility to sickness (rank health in past to now and to others like you). Role/social physical measures limitations in school- as well as nonschool-related activities with friends (does physical health limit ability to do school work and activities with friends). Role/social behavior measures limitations in ability to do school work and activities with friends due to behavioral difficulties (challenges with attention limit your ability to do school work or play specific games with friends). Bodily pain measures bodily discomfort or pain relative to intensity and frequency in the last 4 weeks. Self-esteem measures satisfaction with school and athletic ability, looks/appearance, ability to get along with others, family, and life overall. Family activities measures the frequency of disruption in “usual” family activities over a 4-week recall (does your physical health limit your family from doing spontaneous activities such as going to a movie). Role/social emotional measures limitations in ability to do school work and activities with friends due to emotional difficulties (do challenges with feeling sad or worried limit your ability to do school work or play specific games with friends). Family cohesion asks to rate how well his/her family “gets along with one another” even though family members may disagree and/or get angry.

General QOL refers to enjoying life, feeling life is worthwhile and satisfied with one’s life. Relationships domain describes relationships with others by measuring adult support, caring for others, family relations, freedom, friendships, participation, and peer relations. Environment domains measures the opportunities and obstacles of the youth for good education, liking their neighborhood, monetary resources, personal safety, view of the future, and engagement in activities they chose. Self-domain measures the child’s feelings about themselves by rating belief in self, being oneself, mental and physical health, and spirituality. Total QOL is a summary variable of the other 4 domains above.

Fig 2.

Median and interquartile range (IQR) for CHQ role/social behavioral scale scores by functional levels (GMFCS). NOTE. TDY to level II, P<.002; TYD to levels I and III, P=.07; levels I to II, P=.29; levels I to III, P=.87; levels II to III, P=.37. Adapted from Bjornson.15 Reprinted with permission.

Fig 3.

Median and IQR for CHQ role/social physical scale scores by functional levels (GMFCS). NOTE. TDY to levels I and III, P<.01; TDY to level II, P=.08; levels I to II, P=.31; levels I to III, P=.70; levels I to III, P=.23; levels II to III, P = .31. Adapted from Bjornson.15 Reprinted with permission.

Fig 4.

Median and IQR for CHQ bodily pain scale scores by functional levels (GMFCS). NOTE. TDY to level II, P<.04; TDY to I, P=.81; TDY to III, P=.29; levels I to II, P<.04; levels I to III, P=.37; levels II to III, P<.01. Adapted from Bjornson.15 Reprinted with permission.

Fig 5.

Median and IQR for CHQ physical function scale scores by functional levels (GMFCS). NOTE. TDY to levels I, II, III, P<.002; levels I to II, P=.15; levels I to III, P<.01; levels II to III, P<.02. Adapted from Bjornson.15 Reprinted with permission.

Fig 6.

Median and IQR for CHQ general health perception scale scores by functional levels (GMFCS). NOTE. TDY to levels I and II, P<.01; TDY to level III, P=.12; levels I to II, P=.59; levels I to III, P=.38; levels II to III, P=.22. Adapted from Bjornson.15 Reprinted with permission.

Quality of Life

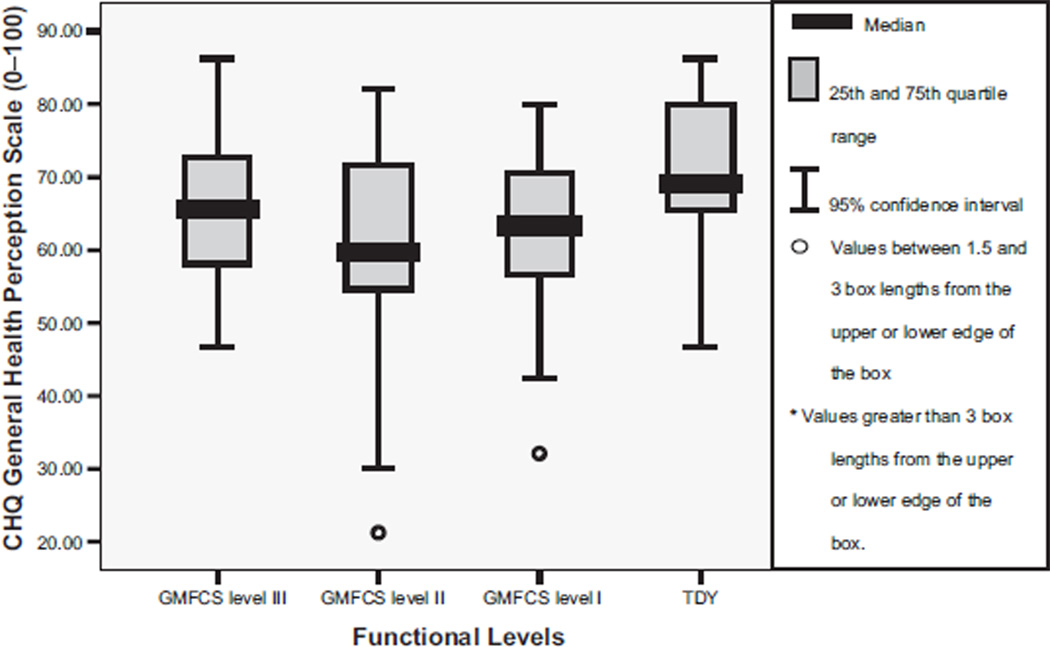

The Cronbach α for the YQOL was .97. The YQOL subscales of general QOL, relationships, environment, self, and total QOL did not differ significantly by self-report between youth with CP and TDY (see table 2). Although there was no significant difference between youth with CP compared with the TDY comparison group, variability by visual analysis of boxplots of reported QOL increased with functional level. This trend was documented for general QOL as well as across all perceptual domains of the YQOL as displayed in figure 7 with the total QOL domain scores.

Fig 7.

Median and IQR for YQOL total QOL scale scores activity by functional levels (GMFCS). Adapted from Bjornson.15 Reprinted with permission.

DISCUSSION

It appears that walking skill is not a primary factor influencing self-reported health status as the data is not ordered by GMFCS level. Despite the clear limitations in walking activity among youth with CP in this sample, the youth in this study sample did not perceive their own QOL as measured by the YQOL to be different than the TDY comparison group. These results are not consistent with previously published child reported HRQOL studies.12 This discrepancy in results of studies may be due to differences in the way in which QOL was assessed. In the prior investigation the PedsQL (which focuses on function and health status) assessed QOL, while in the present study, the YQOL (which assesses aspects of QOL that are independent of health) was used. It appears likely that it is the construct of physical “health” in the published PedsQL data that is reflected in the reported lower HRQOL compared with a normative sample. In the current investigation, we also found differences in self-reported physical function associated with CP levels. In the context of the WHO definition that incorporates the social, environmental, and cultural context of the individual, we did not find differences in QOL that could be attributed to CP. These results are similar to previously documented parental reported health status3,11 and are consistent with the recent child12 and parental13 reported HRQOL data. Self-perceptions of QOL unique from health status and/or HRQOL appear multifactorial for ambulatory youth with CP.

Self-perceived health issues, when measured separately from QOL appear to negatively affect some life experiences for youth with CP compared with TDY. Youth with CP reported lower roles/social behavioral and physical levels compared with age- and sex-matched peers. This is consistent with documented decreased social participation by youth with CP and may warrant psychosocial, physical activity, and/or recreational interventions.23,24 Independent ambulators (levels I and II) with CP in this study perceived themselves to be less healthy than TDY. This may be a function of the age range sampled and history of therapy and medical interventions. Adolescents are more aware of how they fit into their peer group than younger children. The highest functioning groups with CP may need to spend more time with their peers than in structured physical therapy (PT) to enhance their perceptions of “health.”

Nontraditional therapy activities and/or recreational activities may be favorable alternatives and/or complements to regular direct PT interventions. Such activities could vary from Tae Kwon Do, horseback riding, swimming, and skiing to even biking.25,26 Group recreational physical activities have the potential to enhance a child’s sense of participation and/or socialization with peers. Darrah et al27 documented improved muscle strength and perceived physical appearance in adolescents with CP participating in a community fitness program. The authors noted that youth self-reported improved physical appearance after participation in the community fitness program despite no change in athletic competence.

In a study of school-based activity performance and participation in Israel, youth with CP had significantly lower physical activity performance as measured by the School Function Assessment. The youth with CP also participated significantly less often than their typically developing peers in daily school activities (ie, playground games, moving to other areas of the school).24 Motor function has also been shown to be predictive of restrictive participation in mobility, education, and social relations for children with CP.23 The Activity Scale for Kids also addresses participation related to physical activity.28 For high functioning children with CP, the PODCI would be appropriate to measure participation related to musculoskeletal problems. A potential measure of participation across settings and types of activities is also the Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment and the Preferences for Activities of Children.29

It is positive to note that the youth with CP do perceive some aspects of their health as measured by the CHQ-CF87 and all YQOL domains as similar to a comparison group of TDY. The TDY comparison group lives in the same neighborhoods, attend similar schools, and come from some of the same families as the youth with CP. Such a comparison allows control for environmental factors which could influence their perceptions of their QOL or functional health status. These results may be an indication of their individual and/or each family’s ability to accommodate and cope with their mobility limitations within the daily context of their lives.

The high levels of bodily pain reported by youth with CP indicate the need for regular assessment and intervention for pain. There is evidence that pain is overlooked and under-treated in adults with CP.30,31 It appears that pediatric rehabilitation specialists and therapists need to consider issues related to pain in youth with CP across the spectrum of motor function present in this population. Based on a parental report of pain using the Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ-PF28), Houlihan et al32 reported increasing pain as motor function decreased for youth classified at GMFCS levels III to V.

Clinically, pain is commonly considered to be an issue for children with CP who have more severe impairments, are nonambulatory, and are unable to move themselves independently (GMFCS levels IV and V). Therapists and caregivers perceive that such a child with CP has discomfort and/or pain due to the lack of active position changes in wheelchairs or adaptive equipment. Results of this study suggest that pain is not just an issue for the child with CP who cannot walk. It is possible that the PT interventions, which are intended to help patients with CP, may be playing a role in the pain they experience. One of the negative memories of adults with CP reported by Kibele33 was pain related to stretching and bracing with PT. Rehabilitation care providers should assess regularly and explore interventions for pain in youth with CP.

Youth with CP often experience painful flexor, extensor, or adductor muscle spasms related to their movement disorders.34 Movement disorders associated with CP (ie, spasticity, dystonia, athetosis) are thought to lead to musculoskeletal pain later in life due to relative overuse, lack of active position changes, and/or abnormal forces across joints.35 Supporting this premise, Hodgkinson et al35 reported that 47% of sample of 234 nonambulatory adults with CP reported hip pain. In a preliminary sample of 20 children and adolescents with CP, Engel et al36 recently documented that 70% of the sample experienced recurrent chronic pain of moderate intensity on a daily or weekly basis.

Adults with CP have reported significant levels of pain. Andersson and Mattsson37 reported that 174 of 221 adults with CP experienced pain in their muscles and joints. In a retrospective study of adults with CP ages 18 to 76 years, Engel et al30 documented the self-report of chronic pain in 64% of the participants. Of those reporting chronic pain, the majority did not access health care providers for help in coping with their pain. The same study team documented the natural history of pain in adults with CP over a 2-year time span.38 No systematic change in pain levels (positive or negative) was identified. Participants reported pain relief from several interventions, but these were rarely used and/or provided to the adults with CP. The lack of and/or loss of walking as youth with CP enter adulthood may be related to secondary complications such as chronic pain.

This project only reports the perspective of the youth and thus may or may not be in agreement with parents and/or other reporters. In a recent review paper, Eiser and Morse39 described the relationship between child and parent report of QOL. The literature suggests that agreement in report of QOL is influenced by the domain of QOL reported, and whether the child was chronically sick or healthy.39 Domains related to physical function have higher agreement compared to social or emotional issues. Evidence was noted that parents of chronically sick children tend to underestimate their child’s QOL compared with the child’s own perspective.40 In 1998, Theunissen et al41 reported that child-parent agreement was related to age and emotional ratings. The authors reported that older children (10–11y) agreed more with their parents than younger children with the same emotional ratings. In studies of youth with epilepsy and asthma, child-parent agreement has been reported to increase with the child’s age.42,43 Future secondary analysis of data collected with this project will include the parental reports of health status and QOL.

Study Limitations

The cross-sectional design and small sample size limits the generalizability of the findings. A longitudinal design would offer insight into the relative stability of the self-reported levels of health status separate from QOL as adolescents mature into adulthood. The responsiveness and clinical relevance to change over time of child-reported health status, QOL and/or HRQOL measures should be tested within intervention trials for CP. Whether clinical management decisions should be based on child-report, parental report, and/or a combination of data as a child grows warrants further investigation. The influence of current day outlook on only the general QOL domain of the YQOL would be expected as the measure was developed based on the WHO definition of QOL. Three questions of the general QOL domain address how the child feels about aspects of life (ie, enjoyment, satisfaction, is it worthwhile).

CONCLUSIONS

Self-reported health status and QOL as measured by the CHQ and YQOL in youth with CP may offer helpful clinical and epidemiologic information. Health issues related to general health and role social behavioral differences of ambulatory youth with CP compared with age- and sex-matched peers living similar lives may suggest the need for increased psychosocial support and/or recreational physical activities to complement structured PT in adolescence. Pain should be assessed and treated in this population.

Acknowledgments

Supported by a Rehabilitation Science Training Grant (grant no. T32 HD07424), an individual National Research Scientist Award (grant no. F31-NS048740), and the Hester McLaws Nursing Scholarship at the University of Washington. Recruitment and technological support was provided by the Neurodevelopmental Program and the Department of Orthopedic Surgery at Children’s Hospital and Regional Medical Center, Seattle, and the Shriner’s Hospital for Children, Portland, OR, and Spokane, WA.

No commercial party having a direct financial interest in the results of the research supporting this article has or will confer a benefit upon the author(s) or upon any organization with which the author(s) is/are associated.

APPENDIX 1: OUTCOME CATEGORIES BY STUDY OUTCOME MEASURES

| Health Status | Functional Status | Quality of Life |

|---|---|---|

| Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ-CF87) | Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) | Youth Quality of Life (YQOL) |

Footnotes

Supplier

Version 13.0; SPSS Inc, 233 S Wacker Dr, 11th Fl, Chicago, IL 60606.

References

- 1.Stanley F, Blair E, Alberman E. How common are the cerebral palsies? In: Stanley F, Blair E, Alberman E, editors. Cerebral palsies: epidemiology and causal pathways. London: Mac Keith Press; 2000. pp. 22–39. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liptak G, O’Donnell M, Conaway M, et al. The health status of children with moderate to severe cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43:364–370. doi: 10.1017/s001216220100069x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennes J, Rosenbaum P, Hanna SE, et al. Health status of school-aged children with cerebral palsy: information from a population-based sample. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44:240–247. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201002018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. Washington (DC): Government Printing Office; 2000. With understanding and improving health and objectives for improving health. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. World Health Organization: handbook of basic documents. Vol 5. Geneva: Palais des Nations; 1952. Constitution of the World Health Organization; pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization Quality of Life Group. The development of the World Health Organization Quality of Life assessment instrument (WHOQOL) In: Orley J, Kuyken W, editors. Quality of Life assessment: international perspectives. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1994. pp. 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonomi A, Patrick DL, Bushnell DM, Martin M. Validation of the United States’ version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) instrument. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:19–23. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edwards TC, Heubner CE, Connell FA, Patrick DL. Adolescent quality of life. Part I: conceptual and measurement model. J Adolesc. 2002;25:275–286. doi: 10.1006/jado.2002.0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patrick DL, Chiang Y. Measurement of health outcomes in treatment effectiveness evaluations. Med Care. 2000;38(Suppl 9):II14–II25. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200009002-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wake M, Salmon L, Reddihough D. Health status of Australian children with mild to severe cerebral palsy: cross-sectional survey using the Child Health Questionnaire. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2003;45:194–199. doi: 10.1017/s0012162203000379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vargus-Adams J. Health-related quality of life in childhood cerebral palsy. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86:940–945. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varni JW, Burwinkle T, Sherman S, et al. Health-related quality of life of children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: hearing the voices of children. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:592–597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pirpiris M, Gates PE, McCarthy JJ, et al. Function and well-being in ambulatory children with cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26:119–124. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000191553.26574.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bjornson KF, Belza B, Kartin D, Logsdon R, McLaughlin JF. Ambulatory physical activity performance in youth with cerebral palsy and youth who are developing typically. Phys Ther. 2007;87:248–257. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20060157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjornson K. Health, quality of life, and physical activity in youth with cerebral palsy [dissertation] Seattle: Univ Washington; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997;39:214–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1997.tb07414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilkinson GS. [Accessed April 15, 2006];Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT3) 2005 Available at: http://www3.parinc.com/products/product.aspx?Productid_WRAT3. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landgraf J, Abetz L, Ware JE. The CHQ user’s manual. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Patrick DL, Edwards TC, Topolski TD. Adolescent quality of life. Part II: initial validation of a new instrument. J Adolesc. 2002;25:287–300. doi: 10.1006/jado.2002.0471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Topolski TD, Patrick DL, Edwards TC, Huebner C, Connell FA, Mount K. Quality of life and health-risk behaviors among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2001;29:426–435. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00305-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Topolski TD, Edwards TC, Patrick DL, Varley P, Way M, Bueschling D. Quality of life of adolescent males with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Atten Disord. 2004;7:163–173. doi: 10.1177/108705470400700304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lehman AF. A quality of life interview for the chronically mentally ill. Eval Program Plann. 1988;11:51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beckung E, Hagberg G. Neuroimpairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44:309–316. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201002134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schenker R, Coster W, Parush S. Neuroimpairments, activity performance, and participation in children with cerebral palsy mainstreamed in elementary schools. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:808–814. doi: 10.1017/S0012162205001714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fragala-Pinkham MA, Haley SM, Rabin J, Kharasch VS. A fitness program for children with disabilities. Phys Ther. 2005;85:1182–1200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelly M, Darrah J. Aquatic exercise for children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:838–842. doi: 10.1017/S0012162205001775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Darrah J, Wessel J, Nearingburg P, O’Connor M. Evaluation of a community fitness program for adolescents with cerebral palsy. Pediatr Phys Ther. 1999;11:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Young N, Williams JI, Yoshida KK, Wright JG. Measurement properties of the Activities Scale for Kids. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:125–137. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00113-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King G, Law M, King SM, et al. CAPE/PAC Children’s Assessment of Participation and Enjoyment & Preferences for Activities of Children. San Antonio: PsychCorp; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Engel JM, Kartin D, Jensen MP. Pain treatment in persons with cerebral palsy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81:291–296. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200204000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engel JM, Jensen MP, Hoffman AJ, Kartin D. Pain in persons with cerebral palsy: extension and cross validation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:1125–1128. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(03)00263-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Houlihan CM, O’Donnell M, Conaway M, Stevenson R. Bodily pain and health related quality of life in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46:305–310. doi: 10.1017/s0012162204000507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kibele A. Occupational therapy’s role in improving the quality of life of persons with cerebral palsy. Am J Occup Ther. 1989;43:371–377. doi: 10.5014/ajot.43.6.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roscigno CI. Addressing spasticity-related pain in children with spastic cerebral palsy. J Neurosci Nurs. 2002;34:123–133. doi: 10.1097/01376517-200206000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hodgkinson I, Jendrick ML, Duhaut P, Vadot JP, Metton G, Berard C. Hip pain in 234 non-ambulatory adolescents and young adults with cerebral palsy: a cross sectional multicentre study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43:806–808. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201001463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engel JM, Peterina TJ, Dudgeon BJ, McKernan KA. Cerebral palsy and chronic pain: a descriptive study of children and adolescents. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2005;25:73–84. doi: 10.1300/j006v25n04_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersson C, Mattsson E. Adults with cerebral palsy: a survey describing problems, needs, and resources, with special emphasis on locomotion. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43:76–82. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jensen MP, Engel JM, Hoffman AJ, Schwartz L. Natural history of chronic pain and pain treatments in adults with cerebral palsy. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;83:439–445. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200406000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eiser C, Morse M. Can parents rate their child’s health-related quality of life? Results of a systematic review. Qual Life Res. 2001;10:347–357. doi: 10.1023/a:1012253723272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parsons SK, Barlow SE, Levy SL, Supran SE, Kaplan SH. Health-related quality of life in pediatric bone marrow transplant survivors: according to whom? Int J Cancer. 1999;12:46–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(1999)83:12+<46::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Theunissen NC, Vogels TG, Koopman HM, et al. The proxy problem: child report versus parent report in health-related quality of life research. Qual Life Res. 1998;7:387–397. doi: 10.1023/a:1008801802877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ronen GM, Streiner DL, Rosenbaum P the Canadian Pediatric Epilepsy Network. Health-related quality of life in children with epilepsy: development and validation of self-report and parent proxy measures. Epilepsia. 2003;44:598–612. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.46302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Annett R, Bender BD, Lapidus J. Factors influencing parent reports on quality of life for children with asthma. J Asthma. 2003;40:577–587. doi: 10.1081/jas-120019030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]