Abstract

Developing specific medications to treat (+)-methamphetamine (METH) addiction is a difficult challenge because METH has multiple sites of action that are intertwined with normal neurological function. As a result, no small molecule medication for the treatment of METH addiction has made it through the FDA clinical trials process. With the invention of a new generation of protein-based therapies, it is now possible to consider treating drug addiction by an entirely different approach. This new approach is based on the discovery of very high affinity anti-METH monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), which are non-addictive and antagonize METH effects from the blood stream without entering the brain. Due to a very long biological half-life, anti-METH mAbs would only need to be administered once every 2-4 weeks, aiding in patient compliance. As a relapse prevention medication, anti-METH mAbs could reduce or prevent the rewarding effects of a relapse to METH use and thereby improve a patient's probability of remaining in therapy and recovering from their addiction. In this review, we discuss the discovery process of anti-METH mAbs, with a focus on the preclinical development leading to high affinity anti-METH mAb antagonists.

Keywords: Addiction, amphetamines, monoclonal antibodies, pharmacokinetics, rat, vaccines

Introduction

Development of pharmacotherapies for the treatment of addiction is primarily focused on the discovery and testing of small molecule agonists and antagonists. These therapies can act as substitutes or replacements for the drug of abuse, with more or less tolerable effects. For example, methadone serves as a substitute for morphine with similar pharmacologic activity at the opioid receptors, but it produces a more tolerable addiction for the patient. Likewise, nicotine replacement therapy helps patients avoid the many disease-producing constituents in cigarette smoke. The success of these therapies results, in part, from their ability to mimic the effects of a specific drug of abuse at a primary site of action in the brain. Thus, the disease target for most anti-addiction medications is a brain receptor. For stimulant drugs of abuse like (+)-methamphetamine (METH), scientists have tested many small molecule pharmacotherapies that act on the various CNS receptors involved in METH addiction, but have failed to find a viable disease target with demonstrable clinical success.

An alternative therapeutic strategy is to make METH itself the disease target for this addiction therapy. With this approach, slowing or blocking the rate of entry of METH into the brain becomes the therapeutic goal. The mechanism of action for this class of medications is termed pharmacokinetic antagonism, as these therapies act by favorably altering the clearance, volume of distribution and receptor binding of their target drug of abuse. Members of this class of medications include both enzymes and antibodies specific for a drug of abuse.

A systemically administered metabolic enzyme could theoretically antagonize METH effects by increasing the rate of elimination of METH in patients. However, this approach is not currently feasible because of the following reasons. First, and most important, the enzyme system(s) that metabolically clear(s) a major portion of a METH dose is (are) intracellular, membrane-bound cytochrome P450 enzymes, which are not viable candidates for systemic administration into the blood stream. Second, about 45% of a given METH dose is eliminated by the kidney unchanged in the urine without the need for metabolic clearance [1]. Thus enzymatic conversion of METH would not necessarily improve the overall rate of METH clearance, unless the metabolic conversion to an inactive metabolite was much more rapid than renal clearance. For instance, butylcholinesterase (an enzyme in the plasma compartment of the blood stream) metabolizes cocaine to an inactive metabolite in the plasma compartment at an extremely high rate.

Whereas both small molecule pharmacotherapies and enzyme-based therapies have inherent limitations in their viability for treating METH addiction, high affinity anti-METH monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) are a novel treatment approach that demonstrates significant preclinical efficacy [2, 3]. With this approach, patients undergoing cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for METH addiction could be given an anti-METH mAb medication to assist in preventing relapse to METH use. While the primary goal of CBT is to develop the life skills, coping skills and self-motivation necessary to overcome addiction, CBT cannot generally protect the patient from the immediate and compelling urge to use METH when they are away from counseling. Anti-METH mAb could serve as an adjunct to CBT to prevent or blunt any relapse to METH use. Rather than serving as a replacement therapy, the mAb acts to “reduce the high” or the reward that a recovering addict may experience should they self-administer METH while recovering. As a relapse prevention tool, it could significantly improve the probability of recovery from addiction. In this review, we discuss the process by which anti-METH mAbs were discovered, with a focus on the preclinical development leading to high affinity anti-METH mAb antagonists.

Monoclonal Antibodies Versus Active Immunization for Treating Addiction

Passive administration of monoclonal antibodies or production of anti-METH polyclonal antibodies through active immunization with a METH conjugate vaccine could potentially offer beneficial therapy. Both immunotherapeutic strategies have advantages and disadvantages. Active immunization (e.g., [4, 5]) for long-term protection would be significantly less expensive for the patient. However, the amount (or titer) of anti-addiction antibodies that could be generated from the active immunization of a patient is substantially less than the amount of mAb that could be passively infused into a patient. This is because a patient's adaptive immune system serves as an early defense system, which is prepared to remove only low doses of invading antigens (or drugs in this case). It is estimated that the mammalian immune system responds to an invading antigen with <1-10% of its potential production of immunoglobulin G (IgG). This molar amount of IgG binding sites in the body equates to about 2-20 μMol of IgG. A typical “recreational” dose of a drug like phencyclidine (PCP, a dissociative anesthetic drug that is also abused) is considered to be about 5 mg, which is 21 μMol of PCP. Consequently, the repeated administration of PCP would in theory quickly deplete the binding capacity of the antibody reservoir resulting from an active immunization. The doses of METH that are typically self-administered are even higher than those for PCP.

In reality, these calculations are only estimations of circulating IgG levels and do not include the body burden of antibody still in tissues like the spleen, where antibodies are being generated during an active immune response. Furthermore, the results from some of the early preclinical studies testing active immunization are much more impressive than indicated by these estimates [4, 5]. In addition, our preclinical studies in the rat model on the dose of anti-PCP monoclonal antibody needed to neutralize PCP effects suggest that only very small doses of anti-PCP mAb are needed to protect the brain from high concentrations of PCP. In these studies, the dose of antibody (in moles of anti-PCP mAb binding sites) was calculated to be <1:100 of the moles of PCP in the body [6]. Thus, without actual data on the use of an anti-METH conjugate vaccine for treatment of METH addiction, we should not rule out the feasibility of this medical approach. Nevertheless, passive administration of IgG has important advantages over active immunization since the patient treatment dose can be accurately controlled, the total dose of IgG can be substantially greater, and the patients can be offered immediate protection without waiting weeks for an immune response.

The Medical and Societal Impact of Addiction to Meth

The highly addictive nature of METH can cause rapid progression from the infrequent use of relatively low METH doses to an out of control pattern of “binge” use. This phase of the addiction disease is characterized by shorter time intervals between use and escalating METH doses [7]. Since the time interval between each METH dose is minimal relative to the terminal elimination half-life (t1/2λn) of METH (12 hrs in humans [1]), a significant body (and brain) accumulation of the drug occurs. The metabolism of METH in humans also produces a pharmacologically active metabolite, (+)-amphetamine (AMP), which has its own stimulant and addictive properties.

To elicit the euphoric “rush” from METH use, chronic users progressively prefer more rapid routes of administration like inhalation (smoking), nasal insufflation (snorting) and intravenous (iv) injection [8]. The user makes these changes in patterns of use in an attempt to maintain or enhance the euphoric “rush” of pharmacological effects, as increasing use produces tolerance to these effects. Such rapid routes of administration correlate with increased cravings, making it more difficult for users to quit as they progress in their disease [9]. In a patient's drive to achieve the next high, it is not unusual for highly addicted users to self-administer 1 g/day. The significant increase in the frequency and doses of METH leads to an increase in the adverse effects and addiction liability [10].

Medical problems associated with chronic METH use include depression, acute psychosis and schizophrenia-like symptoms [10, 11]. The effects on heavy users are often severe, debilitating and sometimes lethal. There are also reports of long-term neurotoxicity that continue long after the cessation of METH use [12-15]. Studies of large or even moderate METH doses are not medically acceptable in humans and thus animal models of the addiction process must be used to help predict human toxicity and adverse effects.

Animal Models for Studying Immunotherapy for Meth Addiction

Since our anti-METH mAb medications were designed to function as pharmacokinetic antagonists, one of our first studies was to characterize the baseline pharmacokinetics of METH and AMP in the rat brain and other organs [16]. A METH iv bolus dose (1.0 mg/kg) was administered to male Sprague-Dawley rats after which serial blood draws and tissue collection was used to determine METH concentrations over time in the serum and key organ systems. Based on the analysis of the area under the METH concentration-time curves (AUC) after iv dosing, the rank order of METH tissue accumulation is 1) kidney, 2) spleen, 3) brain, 4) liver, 5) heart and 6) serum with METH t1/2λn values ranging from 53-66 min in all tissues. METH concentrations are always highest at the first measured time point after iv dosing, except for the spleen where the maximum concentration occurs at 10 min.

Importantly, the ratio of the brain-to-serum concentrations increases from a value of 7:1 at 2 min up to a peak of about 13:1 by 20 min after dosing. By 2 hrs the brain-to-serum ratio is equilibrated to a constant value of 8:1, where it remains for the remainder of the experiment. AMP (a pharmacologically active metabolite of METH) concentrations peak at 20 min in all tissues, followed by t1/2λn values ranging from 68-75 min. Analysis of the area under the concentration-time curve of AMP (the metabolite) and METH show AMP accounts for approximately one-third to one-half of the drug exposure in all tissues, including the brain.

These data emphasize the important contributions of METH and AMP to the cumulative pharmacological effect profile following iv METH dosing of rats. However, rat pharmacokinetic parameters are significantly different from human parameters. Importantly, METH's t1/2λn in humans is 12 hrs vs 1 hr in rats. Furthermore, a human converts only about 15% of the dose to AMP, whereas the rat converts up to 45-50% of the METH dose to AMP. Finally, the renal (not metabolic) route of elimination accounts for approximately 45% of METH elimination in humans, while metabolism is the major route of elimination in rats [1, 10].

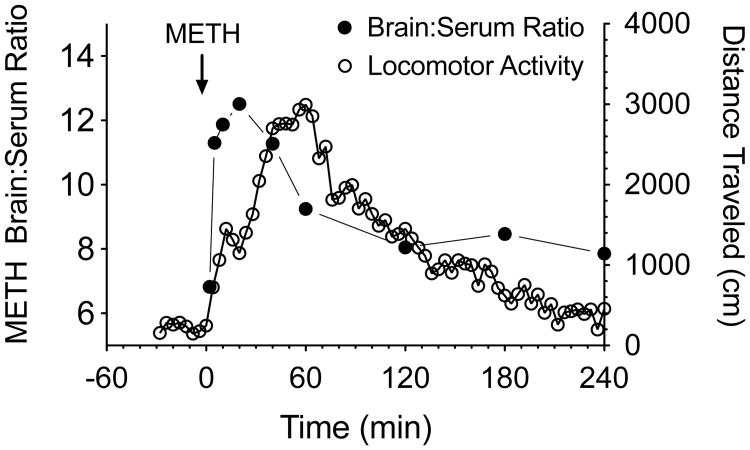

These pharmacokinetic data, along with rat behavioral locomotor data collected in our laboratory [16], suggest the peak behavioral stimulant effects of METH occur slightly after the time to peak brain-to-serum ratio values (see Fig. 1). We think the time course of the increase and then decrease of METH brain-to-serum ratios over time reflects METH binding to, and then release from, pharmacologically active sites. A report of a similar observation for nicotine brain concentrations was reported by Russell and Feyerabend [17] with a rise and fall in the nicotine brain-to-blood ratio after iv bolus administration in mice. The nicotine brain-to-blood ratio remained elevated for 1 h, and then decreased to a relatively constant value for the rest of the study. They suggested, “that the brain cells bind and retain nicotine against a concentration gradient over and above what is determined by lipid solubility”.

Fig. (1).

Time-dependent changes in METH brain to serum concentration ratios over 4 hrs in rats (left axis, solid symbols) versus time-dependent changes in METH-induced locomotor activity over the same time period (right axis, open symbols). These data show that the time course and general shape of the METH brain to serum concentration ratio curve is similar to the METH-induced locomotor activity curve. The major difference in the correlation between these two effect curves is that time to peak effects are offset by about 15-20 min. Data for the brain-to-serum concentrations are from Rivière et al. [16]. Data for the locomotor activity were generated by administering 1 mg/kg of METH (calculated as the free base) sc to male Sprague-Dawley rats (n=4), and then monitoring behavior as described by Byrnes-Blake et al. [44].

Given that the rapid rate of distribution of METH from the blood into the brain is a significant pharmacological factor in the overall observed biological effects, mAb antagonists must significantly block or interfere with this pharmacological process. Since METH peak ratios occur in the brain noticeably earlier than the maximum locomotor effects (see Fig. 1), it is also likely that even if an antibody rapidly removes METH from the brain, there will still be a time lag in the reduction or termination of pharmacological effects. By analogy, when braking is applied to a rapidly moving car, the car does not stop immediately. These data, along with similar findings of PCP partitioning in the brain of rats [18, 19], strongly suggest the need to follow changes in brain drug (i.e., METH) concentrations as a sensitive and predictive measure of anti-addiction mAb efficacy.

Pharmacokinetic Properties of mAbs

Current theory of mAb disposition suggests that the IgG class of immunoglobulins are protected (or “salvaged”) from rapid clearance in mammals by a saturable “protection receptor.” This so-called neonatal fragment crystallizable receptor (FcRn) [20-22] also facilitates IgG transport from the mother to her newborn infants [23]. In this salvage pathway, IgG non-specifically enters vascular endothelial cells where FcRn binds to the Fc domain of IgG at the acidic pH of the endosome and shuttles IgG back to the cell surface avoiding intracellular degradation (see Roopenian and Akilesh [24] for a review). This pathway provides IgG (and albumin) with the longest half-life of any serum protein. The human IgG pharmacokinetic profile is quite similar in males and non-pregnant females with a t1/2λn of ∼18-21 days [25, 26]. In the rat the t1/2λn is ∼7-10 days. Importantly, mAb pharmacokinetics in humans and rats appear dose- and sex-independent indicating that rats can function as a viable preclinical species for the study of mAb medications.

Disposition of mAbs is radically different and much more complex in pregnant female rats. Results from studies investigating the pharmacokinetics of anti-PCP and anti-METH mAbs in pregnant rats in our laboratory show that systemic clearance, volume of distribution and t1/2λn all change significantly over the course of pregnancy in an intriguing pattern. Our most interesting finding during pregnancy is that each pharmacokinetic shift occurs over a 2-3 day period that is precisely timed to coincide with biological changes across each of the three phases of rat pregnancy [22]. Furthermore, during each of these three phases of rat pregnancy, mAb disposition appears to be constant and dose-independent. While there is no available evidence that these unique changes occur during human pregnancy, we think these findings could be an important consideration for the preclinical development of mAb medications, especially in the context of developmental biology overlaid with substance abuse. It is also important to realize that METH abuse has expanded in the human population over time to include an approximately equal number of male (55%) and female (45%) users [27, 28], and these female users are most often in their child bearing years.

Studies of the fate of anti-PCP and anti-METH mAbs over the last several decades in male and female rats suggest that mAbs are neuroprotective without crossing the blood brain barrier (BBB). Under normal physiologic conditions, mAbs do not readily cross the BBB, but if there is a loss of BBB integrity, mAbs are actively transported out of the brain by the FcRn [29]. Our primary evidence for the lack of penetration of the BBB by anti-addiction mAbs comes from experimental data from studies of the disposition of anti-PCP and anti-METH mAbs in the presence and absence of PCP and METH, respectively (e.g., [6, 30, 31]). When high affinity anti-PCP or anti-METH mAbs are administered to rats in the presence of PCP or METH, respectively, the brain concentration of each drug is significantly decreased relative to buffer-treated control animals, suggesting that the mAbs retain each drug of abuse outside the CNS.

The Relationship Between mAb Affinity for Drugs of Abuse and Efficacy

Our research shows that a single dose of a high affinity anti-PCP Fab (the antigen binding fragment of a full-length IgG; KD = 1.8 nM) can effectively reverse the effects of PCP overdose in rats [32]. The full-length anti-PCP mAb (KD = 1.3 nM) [33] also provides immediate protection from a PCP overdose with greater and longer lasting reduction in brain PCP levels [6, 30]. Importantly, only one dose of anti-PCP mAb (IgG) is needed to protect against PCP-induced behavioral effects for over 2 weeks. Anti-PCP mAb protective effects are achieved even though the dose of PCP far exceeds the stoichiometric binding capacity of the mAb, and this protection occurs even in the presence of repeated iv challenge doses of PCP [34]. We have observed these results with both anti-METH and anti-PCP mAbs [6, 30]. We hypothesize that several factors contribute to the unexpected effectiveness at relatively low doses of mAb to target drug. First, the brain is the primary organ for METH addiction and behavioral effects so it is essential to lower or block METH partitioning into this critical organ. Second, the vascular cerebral space represents an extremely small volume relative to the entire systemic vascular space, and the BBB restricts mAb (and mAb bound to METH) to the plasma compartment of the vascular space. In fact, mAbs have a very small apparent volume of distribution (Vd) of 0.142 l/kg vs METH's very high Vd of 9 l/kg [9]. Third, unbound METH freely and rapidly equilibrates across the blood-brain barrier, but the actual fraction of the total METH dose in the brain is extremely small (0.1–0.2% for METH and PCP [7]). Taken together, these factors work in concert to allow temporarily greater drug-mAb occupancy with each pass through the brain, which then lowers brain concentrations and thereby reduces METH effects.

This means mAb protection from METH- or PCP-induced effects continues even when the molar dose of each drug is in significant excess to the molar dose of mAb binding sites. This finding of long-lasting protection despite relatively low doses of mAb is extremely important since a major criticism of anti-drug mAb therapies is that their effectiveness is limited by stoichiometric antigen-binding capacity.

Undoubtedly a major reason for anti-PCP mAb's effectiveness is its very high affinity for PCP. Our calculations show the affinity of anti-PCP mAb for PCP is about 80-fold greater than the affinity of PCP for the N-methyl D-aspartate receptor [18, 30], which is the primary site of action for PCP in the brain. Although it may seem obvious that high affinity mAbs provide an important clinical advantage relative to low affinity mAbs, there is likely an optimal balance between in vivo drug association with the antibody (to neutralize the drug of abuse and block biological effects) and drug dissociation from the mAb (to permit clearance of the drug and regeneration of the binding capacity).

In a study by Byrnes-Blake et al. [35] using early prototypes of our anti-METH mAbs, a very high (KD = 11 nM) and a low (KD = 250 nM) affinity anti-METH mAb were tested for their ability to alter METH pharmacokinetics and acute METH-induced locomotor activity. The mAbs were administered either prior to METH administration in a pretreatment model, or after administration of METH, in a model simulating reversal of a drug overdose. The higher affinity mAb was significantly more effective than the lower affinity mAb in both therapeutic models. Nevertheless, both mAbs appeared less effective at blocking or reducing METH-induced behavior if administered as a pretreatment before dosing the rats with METH. These data demonstrated that mAb affinity and time of administration (relative to METH dosing) are critical determinants of therapeutic success. However, we later determined that these seemingly confusing results following pretreatment with high affinity mAb6H4 was caused by a rapid loss of mAb6H4 METH binding function in vivo. This finding is discussed in more detail in the next section.

What We Learned From The Unexpected Case of Anti-Meth mAb6h4

Over the course of several years of study, we began to suspect that the in vivo METH-binding function of our highest affinity anti-METH mAb (mAb6H4, METH KD = 4 nM) might be significantly reduced in some preclinical scenarios even though the initial characterization of the mAb predicted promising in vivo efficacy. In our earliest determination, the KD (affinity) value of mAb6H4 appeared to be 11 nM. As a note, improvements in our assay sensitivity now show the KD value is actually 4 nM.

We began these studies realizing that the mAbs had potential as a treatment for METH overdose and as a protective pre-treatment for patients who needed to block or at least reduce the harmful effects of an uncontrolled relapse to METH use during addiction behavioral treatments. The challenge for the anti-METH mAb antagonist is different in these two scenarios. In the METH overdose model, the majority of the METH molecules are already diffused into tissues throughout the body. Therefore, the mAb will first bind to METH in the blood stream and then to METH from tissues like the brain, which can very rapidly re-equilibrate with the blood stream. In the mAb pre-treatment model, all of the METH molecules enter through the blood stream and the mAb is initially presented with the maximum possible METH dose because the METH has not had time to distribute into tissues, which are either non-critical or critical to METH effects. In this treatment scenario, the initial dose of METH could initially overwhelm the antibody binding capacity. Therefore, we routinely test our antibody medications for safety and efficacy in both treatment scenarios.

In an overdose model of METH abuse, where high doses of METH were administered prior to mAb dosing, mAb6H4 proved to be much more efficacious than a lower affinity (KD = 250 nM) mAb in reducing METH-induced stimulant effects, like horizontal locomotion, as we predicted due to its higher affinity for METH. However, when mAb6H4 was administered prior to a METH challenge (i.e., a pre-treatment model), mAb6H4 appeared to lose efficacy rather quickly and could only alter METH-induced locomotor effects if the METH was administered within the first 24 hrs after mAb6H4 administration. It also appeared as if mAb6H4 had similar efficacy to the very low affinity (KD = 250 nM) anti-METH mAb. This finding made it appear as if the in vivo efficacy of anti-METH mAbs was not predictable from the in vitro affinity. The actual reason for time-dependent changes in the efficacy of this and some of our other early prototype anti-METH mAbs turned out to be more complicated.

To determine the immunological and proteomic factors that could be affecting the in vivo function of mAb6H4, we studied the in vitro immunochemical properties, in vivo pharmacokinetics, and in vivo functional properties of five prototype anti-METH mAbs (including mAb6H4), with KD values from 4-250 nM [36]. Each of the mAbs was generated from immunization with a unique METH-like hapten. It was hypothesized that hapten structure would be the major determinate of in vivo mAb function. The five haptens varied in one or more of the following chemical characteristics: 1) they contained a 4-10 molecule spacer arm (i.e., 2, 6 or 10) between the METH-like structure and the carrier protein, 2) they were attached to the METH structure at either the meta or para position of the METH aromatic ring, 3) they were linked to three different carrier proteins, which served as the antigens [37].

The affinity constants and cross-reactivity profiles for the mAbs were determined along with their pharmacokinetic profiles. The pharmacokinetic results from a one-month study in Sprague Dawley rats showed there were no substantive differences in pharmacokinetic properties of the mAbs (e.g., t1/2λn ranged from 6.1–6.9 days for all 5 mAbs) [36]. Thus the mAb proteins were not cleared at different rates and they did not have substantively different volumes of distribution. This also meant that the intravascular administration of the mAbs would result in the same relative serum concentrations throughout the experiment, and differences in the mAb METH-binding function in vivo could not be attributed to differences in clearance of the mAb. The pharmacokinetic profiles of these mAbs were also quite similar to results from previously studied mouse mAbs in rats [38]. It is also worth noting that two of the mAbs (mAb6H4 and mAb6H8) were of the IgG1 subclass while mAb4G9 was an IgG2b. Previous studies show murine IgG1 and IgG2 subclasses with light chains have similar pharmacokinetic parameters [39]. It is known that different mAb isotypes have different affinities for Fc [40], which potentially could affect in vivo effector functions. Fortunately, the mAb isotype did not appear to be a factor in the ability to antagonize or prevent effects of METH in our studies.

In the next set of experiments, we infused rats with METH using sc osmotic minipumps for 14 days. Since METH has an approximately 1 hr t1/2λn in rats, steady-state METH concentrations were reached in 4-7 hrs. This constant METH infusion meant that 50% of the METH dose was replaced every hour during the two-week study. Each mAb was administered in separate groups of rats at a dose equimolar to the METH body burden and the effect of each mAb on METH serum concentration was determined over time. Importantly, functional longevity (ability to increase METH serum levels over time) did not correlate with mAb affinity for METH, and the antigenic carrier protein did not appear to be a factor. However, we found that four of the mAbs appeared to lose METH-binding capacity at a significantly more rapid rate than the other antibody in the study. Furthermore, the very high affinity mAb6H4 raised METH serum levels to the same extent and over a similar time-course to the very low affinity mAb6H8 (METH KD = 250 nM).

We hypothesized that the most effective antibodies would maintain the highest METH concentrations in the blood stream. Indeed, METH has such a large volume of distribution (12 l/kg in the rat) that very little of the total dose of METH resides in the blood stream for long. Because the mAbs have a very small volume of distribution (approximately equal to three times the extracellular fluid space), high affinity binding of METH to the mAbs will substantially increase METH serum concentrations (and serum protein binding) by substantially lowering the METH apparent volume of distribution.

Of the tested mAbs, only mAb4G9 (METH KD = 34 nM) was capable of prolonged efficacy, as judged by the ability to maintain prolonged, high METH serum concentrations. More recent determinations of the METH dissociation constant by improved methods show a KD value of 16 nM [41] for mAb4G9. Mab4G9 caused a 16-fold increase in METH serum area under the METH concentration-time curves from the start of the measures until day compared to animals infused with METH but without mAb treatment. The value for all four other mAbs (including mAb6H4) only increased METH serum values 4.8–5.6-fold over METH infused-buffer treated controls. This indicated loss of function.

MAb4G9 also maintained high AMP serum concentrations, along with significant reductions in METH and AMP brain concentrations. MAb4G9 was produced by immunizing mice with a 10 molecule linker attached to a METH-like base molecule, while all other antibodies were generated with a short linker of only 4-6 molecular spacers. These data support the hypothesis that hapten structure, and in particular the length of the spacer attachment arm, can directly affect the long-term efficacy of the resulting mAbs. The combination of broad specificity for METH-like drugs, high affinity, and prolonged action in vivo suggested mAb4G9 was a potentially efficacious medication for treating human METH-related medical diseases.

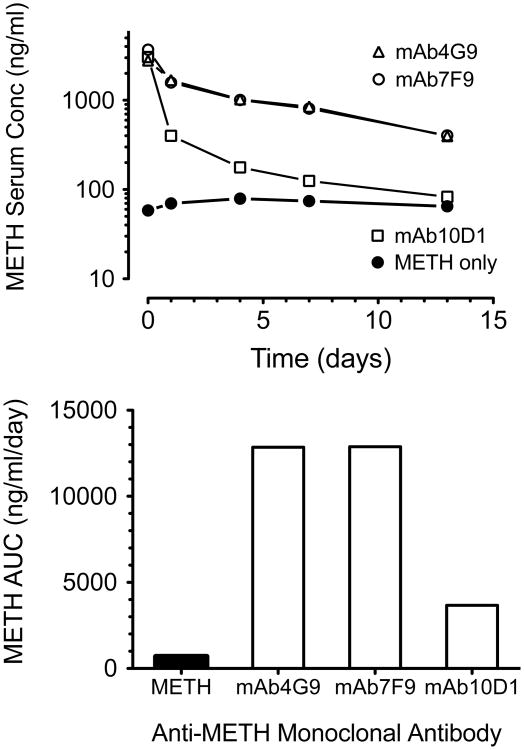

More recent unpublished studies in our lab show that four of five mAbs generated from the same longer spacer arm hapten as mAb4G9 also have prolonged duration of action. Thus we hypothesize a longer spacer arm between the METH backbone structure and the antigen is somehow protective against inactivation. One of these antibodies, mAb7F9 (KD = 9 nM) has emerged as our lead candidate on which to base a human anti-METH mAb medication [41]. Fig. (2) shows the excellent long-term METH-binding function of mAb7F9 in the presence of a constant METH infusion.

Fig. (2).

Example of a preclinical anti-METH mAb in vivo functional assay used to make decisions about which mAbs to carry forward, and which mAbs to reject during the medications discovery process. The figure shows the changes in METH in vivo binding by anti-METH monoclonal antibodies during a 13 day METH (5.6 mg/kg/day) sc infusion via osmotic minipumps. Once METH achieved steady-state levels (pre-mAb) in each of the Sprague-Dawley rats (n = 2 per group), single doses of vehicle treatment (METH only) or treatment with three different anti-METH mAbs were given as an iv bolus (180 mg/kg, equimolar in binding sites to the METH body burden). Serum samples were collected before the mAb treatment and at various time points after mAb treatment for determination of METH concentrations over time (upper panel) by liquid chromatography mass spectrometry [45]. Values represent the mean METH concentration of each group for each time point. METH concentrations for mAb4G9 and mAb7F9 were virtually superimposable (upper graph), and the data (lower graph) yielded similar data for these two mAbs over the 13 day experiment. The data for mAb10D1 (METH KD = 34 nM) suggested its METH binding function decreased quickly during the first few days of the experiment. Based on these data, mAb4G9 and mAb7F9 would pass this testing, and mAb 10D1 would be excluded from further development as a medication.

In summary, these studies demonstrate the importance of both in vitro and in vivo characterization of the functional properties of therapeutic mAbs. These data also suggest that careful structure-activity studies with mAbs generated from a range of haptens can reveal opimal choices for the discovery of vaccines for use in active immunization. Our studies also show that mAb in vivo function is not always predicted from in vitro immunochemical characterization. Despite having multifold higher affinity for METH and similar PCKN characteristics, mAb6H4 was significantly worse at antagonizing METH effects than mAb4G9. Pharmacokinetic studies of mAb medications are also important, but could lead to inaccurate assumptions regarding longer-term in vivo efficacy, since mAb t1/2λn does not correlate with efficacy in these experiments. Studies are underway to address the potential mechanisms facilitating the loss of in vivo METH-binding function of some anti-METH mAbs (e.g., mAb6H4). Nevertheless, these results underscore the need for extensive preclinical characterization of mAb therapeutics, and highlight the importance of prolonged in vivo METH-binding function and efficacy of anti-METH mAb4G9 and mAb7F9.

Anti-Meth mAb Effects on Meth Self-Administration

Because these anti-METH mAbs are being developed for the treatment of human METH addiction, studies of anti-METH mAb efficacy in a rat METH self-administration model of addiction were conducted [42]. As in previous studies of anti-METH effects on METH overdose (see earlier section), low (mAb6H8, KD = 250 nM) and high (mAb6H4 KD = 11 nM) affinity mAbs were studied. MAb6H8 was given in a 1 g/kg dose, 1 day prior to the start of several daily 2-hr self-administration sessions. MAb6H8′s efficacy in these studies depended on the unit dose of METH provided for the rats; that is, mAb6H8 was associated with an increased rate of self-administration at a METH unit dose of 0.06 mg/kg; it appeared to have minimal effects on the self-administration rate of a METH unit dose of 0.03 mg/kg; and it appeared to decrease the self-administration rate of a unit dose of 0.01 mg/kg METH down to the level of saline control values. The mAb6H8-induced changes in self-administration rates occurred early in the self-administration sessions and lasted for 3-7 days.

When mAb6H4 (KD = 11 nM) was administered at either a 0.6 or a 1 g/kg dose 1 day prior to the first of several self-administration sessions, it produced similar effects to mAb6H8, despite mAb6H4′s 62-fold greater affinity for METH. At the time we did not understand why mAb6H4 was not significantly more potent than mAb6H8, however we now know (as discussed in the previous section) mAb6H4 loses significant METH-binding function within a few hours of dosing, which made it appear similar in potency to the much lower affinity mAb6H8.

In these early studies, extremely large mAb doses that would not be financially or technically feasible in humans were given and it has not been determined if significantly lower doses might also produce beneficial effects. Nevertheless these studies show anti-METH mAbs can block or reduce METH's effects as a reinforcer of METH self-administration. Although neither of these mAb medications was considered optimal for treating METH abuse, the experiments demonstrate that anti-METH mAbs can attenuate self-administration of METH, providing clinically meaningful preclinical evidence of efficacy. We have recently completed studies of the therapeutic effects of significantly higher affinity anti-METH mAbs (at significantly lower mAb doses) on the prevention of relapse to METH use in animal models (manuscript in preparation).

Characteristics of A Human Anti-Meth Monoclonal Antibody and Clinical Trials

Plans for clinical trials of the first mAb medication for the treatment of METH abuse are underway. These will be studies of a mouse-human chimeric antibody, which has the METH-binding variable regions of the original murine antibody (mAb7F9, KD= 9 nM), and the constant domains of a human IgG2κ antibody.

This new mAb was designed to be as safe as possible for human administration. First, an IgG2 isotype was chosen because of the lower potential for Fc effector function when compared to IgG1 or IgG3 [43]. Second, its ability to bind and inactivate METH does not require interaction with an Fc receptor because the binding components are on the variable regions. Third, due to its very small size, METH (molecular weight of 149 Da) acts as a monovalent molecule that is incapable of generating the multiple IgG interactions needed to produce Fc effector functions. This reduces or prevents the potential for antibody aggregation in the serum or on cell surfaces, which further reduces the probability of Fc effector functions.

Because the target of the mAb (i.e., METH) is not endogenous in humans, the initial safety studies can be conducted in healthy humans subjects, without the need to study addicted patients. Subsequent Phase 1 studies of the interactions of METH and the mAb will involve METH users, and the opportunity to discover both safety and preliminary efficacy data. Phase 2 studies will be designed to be pivotal, and if successful could provide the opportunity for an early entry point into treatment of METH addiction. This could be allowed because of the unmet medical need for treating METH addiction. Because this will be a first of kind study of a highly specific monoclonal antibody for the treatment of addiction, these clinical studies will likely have a large impact on the use of active immunization and monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of addiction related diseases.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA07610, DA11560, RC2DA028915, DA031944, F30 DA029372 to WTA), and the National Center for Research Resources (1UL1RR029884).

Abbreviations

- Abs

Antibodies

- AMP

(+)-Amphetamine

Area under the serum concentration-versus-time curve from time zero to day 13

- BBB

Blood brain barrier

- CBT

Cognitive behavioral therapy

- FcRn

Fragment crystallizable receptor

- IgG

Immunoglobulin G

- KD

Dissociation constant

- mAbs

Monoclonal antibodies

- METH

(+)-Methamphetamine

- t1/2λn in

Terminal elimination half-life

- Vd

Apparent volume of distribution

Footnotes

Conflicts Of Interest: S.M.O. and W.B.G. have financial interests in and serve as Chief Scientific Officer and Chief Medical Officer, respectively, of InterveXion Therapeutics LLC (Little Rock, AR), a pharmaceutical biotechnology company focused on treating human drug addiction with antibody-based therapy.

Protection Of Human Subjects And Animals In Research: All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as adopted and promulgated by the National Institutes of Health, and were performed with the prior approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

References

- 1.Cook CE, Jeffcoat AR, Hill JM, Pugh DE, Patetta PK, Sadler BM, White WR, Perez-Reyes M. Pharmacokinetics of methamphetamine self-administered to human subjects by smoking S-(+)-methamphetamine hydrochloride. Drug Metab Dispos. 1993;21:717–723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kosten T, Owens SM. Immunotherapy for the treatment of drug abuse. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;108:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gentry WB, Rüedi-Bettschen D, Owens SM. Anti-(+)- methamphetamine monoclonal antibody antagonists designed to prevent the progression of human diseases of addiction. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;88:390–393. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2010.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrera MR, Ashley JA, Parsons LH, Wirsching P, Koob GF, Janda KD. Suppression of psychoactive effects of cocaine by active immunization. Nature. 1995;378:727–730. doi: 10.1038/378727a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox BS, Kantak KM, Edwards MA, Black KM, Bollinger BK, Botka AJ, French TL, Thompson TL, Schad VC, Greenstein JL, Gefter ML, Exley MA, Swain PA, Briner TJ. Efficacy of a therapeutic cocaine vaccine in rodent models. Nat Med. 1996;2:1129–1132. doi: 10.1038/nm1096-1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laurenzana EM, Gunnell MG, Gentry WB, Owens SM. Treatment of adverse effects of excessive phencyclidine exposure in rats with a minimal dose of monoclonal antibody. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:1092–1098. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.053140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho A, Melega W. Patterns of methamphetamine abuse and their consequences. J Addictive Dis. 2001;21:21–34. doi: 10.1300/j069v21n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rawson RA, Condon TP. Why do we need an Addiction supplement focused on methamphetamine? Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl 1):1–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galloway GP, Singleton EG, Buscemi R, Baggott MJ, Dickerhoof RM, Mendelson JE. Methamphetamine Treatment Project Corporate Authors: An examination of drug craving over time in abstinent methamphetamine users. Am J Addict. 2010;19:510–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho AK. Ice: a new dosage form of an old drug. Science. 1990;249:631–634. doi: 10.1126/science.249.4969.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seiden LS, Sabol KE, Ricaurte GA. Amphetamine: effects on catecholamine systems and behavior. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1993;33:639–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.33.040193.003231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sekine Y, Ouchi Y, Takei N, Yoshikawa E, Nakamura K, Futatsubashi M, Okada H, Minabe Y, Suzuki K, Iwata Y, Tsuchiya KJ, Tsukada H, Iyo M, Mori N. Brain serotonin transporter density and aggression in abstinent methamphetamine abusers. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:90–100. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCann UD, Wong DF, Yokoi F, Villemagne V, Dannals RF, Ricaurte GA. Reduced striatal dopamine transporter density in abstinent methamphetamine and methcathinone users: evidence from positron emission tomography studies with [11C]WIN-35,428. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8417–8422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08417.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ernst T, Chang L, Leonido-Yee M, Speck O. Evidence for long-term neurotoxicity associated with methamphetamine abuse: A 1H MRS study. Neurology. 2000;54:1344–1349. doi: 10.1212/wnl.54.6.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volkow ND, Chang L, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Franceschi D, Sedler M, Gatley SJ, Miller E, Hitzemann R, Ding YS, Logan J. Loss of dopamine transporters in methamphetamine abusers recovers with protracted abstinence. J Neurosci. 2001;21:9414–9418. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-23-09414.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rivière GJ, Gentry WB, Owens SM. Disposition of methamphetamine and its metabolite amphetamine in brain and other tissues in rats after intravenous administration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:1042–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Russell MA, Feyerabend C. Cigarette smoking: a dependence on high-nicotine boli. Drug Metab Rev. 1978;8:29–57. doi: 10.3109/03602537808993776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Proksch JW, Gentry WB, Owens SM. The effect of rate of drug administration on the extent and time course of phencyclidine distribution in rat brain, testis, and serum. Drug Metab Dispos. 2000;28:742–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pitas G, Laurenzana EM, Williams DK, Owens SM, Gentry WB. Anti-phencyclidine monoclonal antibody binding capacity is not the only determinant of effectiveness, disproving the concept that antibody capacity is easily surmounted. Drug Metab Dispos. 2006;34:906–912. doi: 10.1124/dmd.105.005934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brambell F, Hemmings W. A theoretical model of gamma-globulin catabolism. Nature. 1964;203:1352–1354. doi: 10.1038/2031352a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lobo ED, Hansen RJ, Balthasar JP. Antibody pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. J Pharm Sci. 2004;93:2645–2668. doi: 10.1002/jps.20178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hubbard JJ, Laurenzana EM, Williams DK, Gentry WB, Owens SM. The fate and function of therapeutic antiaddiction monoclonal antibodies across the reproductive cycle of rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;336:414–422. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.175083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu W, Zhao Z, Zhao Y, Yu S, Zhao Y, Fan B, Kacskovics I, Hammarström L, Li N. Over-expression of the bovine FcRn in the mammary gland results in increased IgG levels in both milk and serum of transgenic mice. Immunology. 2007;122:401–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02654.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Roopenian DC, Akilesh S. FcRn: the neonatal Fc receptor comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:715–725. doi: 10.1038/nri2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arizono H, Ishii S, Nagao T, Kudo S, Sasaki S, Kondo S, Kiyoki M. Pharmacokinetics of a new human monoclonal antibody against cytomegalovirus. First communication: plasma concentration, distribution, metabolism and excretion of the new monoclonal antibody, regavirumab after intravenous administration in rats and rabbits. Arzneimittelforschung. 1994;44:890–898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bichler J, Schöndorfer G, Pabst G, Andresen I. Pharmacokinetics of anti-D IgG in pregnant RhD-negative women. BJOG. 2003;110:39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Anglin MD, Burke C, Perrochet B, Stamper E, Dawud-Noursi S. History of the methamphetamine problem. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32:137–141. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen JB, Greenberg R, Uri J, Halpin M, Zweben JE. Women with methamphetamine dependence: research on etiology and treatment. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;(4):347–351. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2007.10399896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Y, Pardridge WM. Mediated efflux of IgG molecules from brain to blood across the blood-brain barrier. J Neuroimmunol. 2001;114:168–172. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(01)00242-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Proksch JW, Gentry WB, Owens SM. Anti-phencyclidine monoclonal antibodies provide long-term reductions in brain phencyclidine concentrations during chronic phencyclidine administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;292:831–837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laurenzana EM, Byrnes-Blake KA, Milesi-Hallé A, Gentry WB, Williams DK, Owens SM. Use of anti-(+)-methamphetamine monoclonal antibody to significantly alter (+)-methamphetamine and (+)-amphetamine disposition in rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 2003;31:1320–1326. doi: 10.1124/dmd.31.11.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valentine JL, Owens SM. Antiphencyclidine monoclonal antibody therapy significantly changes phencyclidine concentrations in brain and other tissues in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;278:717–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McClurkan MB, Valentine JL, Arnold L, Owens SM. Disposition of a monoclonal anti-phencyclidine Fab fragment of immunoglobulin G in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;266:1439–1445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hardin JS, Wessinger WD, Wenger GR, Proksch JW, Laurenzana EM, Owens SM. A single dose of monoclonal anti-phencyclidine IgG offers long-term reductions in phencyclidine behavioral effects in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:119–126. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Byrnes-Blake KA, Laurenzana EM, Landes RD, Gentry WB, Owens SM. Monoclonal IgG affinity and treatment time alters antagonism of (+)-methamphetamine effects in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;521:86–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Laurenzana E, Hendrickson H, Carpenter D. Functional and biological determinants affecting the duration of action and efficacy of anti-(+)-methamphetamine monoclonal antibodies in rats. Vaccine. 2009;27(50):7011–7020. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peterson EC, Gunnell M, Che Y, Goforth RL, Carroll FI, Henry R, Liu H, Owens SM. Using hapten design to discover therapeutic monoclonal antibodies for treating methamphetamine abuse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322:30–39. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.117150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bazin-Redureau MI, Renard CB, Scherrmann JM. Pharmacokinetics of heterologous and homologous immunoglobulin G, F(ab')2 and Fab after intravenous administration in the rat. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1997;49:277–281. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1997.tb06795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Montaño RF, Morrison SL. Influence of the isotype of the light chain on the properties of IgG. J Immunol. 2002;168:224–231. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.1.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roskos LK, Davis CG, Schwab GM. The clinical pharmacology of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Drug Dev Res. 2004;61:108–120. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carroll FI, Abraham P, Gong PK, Pidaparthi RR, Blough BE, Che Y, Hampton A, Gunnell M, Lay JO, Peterson EC, Owens SM. The synthesis of haptens and their use for the development of monoclonal antibodies for treating methamphetamine abuse. J Med Chem. 2009;52:7301–7309. doi: 10.1021/jm901134w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McMillan DE, Hardwick WC, Li M, Gunnell MG, Carroll FI, Abraham P, Owens SM. Effects of murine-derived anti-methamphetamine monoclonal antibodies on (+)-methamphetamine self-administration in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;309:1248–1255. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.061762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang XR, Song A, Bergelson S, Arroll T, Parekh B, May K, Chung S, Strouse R, Mire-Sluis A, Schenerman M. Advances in the assessment and control of the effector functions of therapeutic antibodies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10:101–111. doi: 10.1038/nrd3365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rivière GJ, Byrnes KA, Gentry WB, Owens SM. Spontaneous locomotor activity and pharmacokinetics of intravenous methamphetamine and its metabolite amphetamine in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:1220–1226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hendrickson H, Laurenzana E, Owens SM. Quantitative determination of total methamphetamine and active metabolites in rat tissue by liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometric detection. AAPS J. 2006;8:E709–E717. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]