Abstract

Objective

To examine the role of anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents in predicting work disability in subjects with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

We studied 953 subjects with rheumatologist-diagnosed RA from a US cohort using a nested, matched, case–control approach. Subjects provided data on medication usage and employment every 6 months for 18 months, were employed at baseline, and were age <65 years at last followup. Cases were subjects who were not employed at followup (n = 231) and were matched ~3:1 by time of entry into the cohort to 722 controls who were employed at followup. Risk of any employment loss, or loss attributed to RA, at followup as predicted by use of an anti-TNF agent at baseline was computed using conditional logistic regression. Stratification on possible confounding factors and recursive partitioning analyses were also conducted.

Results

Subjects’ mean age was 51 years, 82% were female, 92% were white, and 72% had more than a high school education. Nearly half (48%) used an anti-TNF agent at baseline; characteristics of anti-TNF agent users were similar to nonusers. In the main analyses, anti-TNF use did not protect against any or RA-attributed employment loss (odds ratio [95% confidence interval] 1.1 [0.7–1.6] versus 0.9 [0.5–1.5]). However, a protective effect was found for users with disease duration <11 years (odds ratio [95% confidence interval] 0.5 [0.2–0.9]). In recursive partitioning analyses, age, RA global severity, and functional limitation played a much greater role in determining employment loss than anti-TNF agent use.

Conclusion

Anti-TNF agent use did not protect against work disability in the main analyses. In stratified analyses, their use was protective among subjects with shorter RA duration, whereas in nonparametric analyses, age and disease factors were the prominent predictors of work disability.

INTRODUCTION

In the past, the indirect costs of rheumatoid arthritis (RA; chiefly from work disability) were often higher than direct costs of medical care (1–3). However, direct costs have increased substantially since the advent of expensive biologic agents, notably the anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents (4,5). It is hoped that use of these agents will reduce work disability and thereby offset higher direct costs (6 – 8). Given that anti-TNF agents provide good control of symptoms, reduce functional limitation, and slow radiologic progression (6,9,10), there are good reasons to believe their use will reduce work disability.

Work disability includes both loss of employment and reduced productivity, i.e., absenteeism and reduced work output. The number of studies that have examined work disability outcomes in subjects with RA treated with anti-TNF agents is still relatively small. Thus far, these studies suggest that use of these agents results in improved productivity (10 –13). The costliest outcome, however, is loss of employment. Studies examining this outcome have used data from subjects in anti-TNF clinical trials, and only 1 found a significant improvement in employment rate among anti-TNF (etanercept) users compared with nonusers (11). That finding must be interpreted with caution because the study compared subjects from clinical trials with patients in an observational cohort. A randomized trial to fully test the effect of anti-TNF agents on employment outcomes has been recommended (6,11), but is currently recognized as probably unfeasible, given the clinical effectiveness of these agents.

The purpose of our study was to examine the role of anti-TNF agent use in predicting employment loss in subjects with RA. The chief advantages of our study compared with prior studies are that all subjects were from the same observational cohort, most subjects were recruited from clinical practices rather than pharmaceutical trials, and our definition of work disability was the same as in most studies. We used several recommended study design and data analysis methods to reduce the effect of possible confounding from extraneous factors (14).

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Data source and collection

We used data from participants in the National Data Bank (NDB) longitudinal study of RA outcomes; individuals are added to this observational cohort continuously, and ~8% decline to participate per year. All participants have rheumatologist-diagnosed RA and reside in the US. Participants are recruited from 2 sources: 1) approximately two-thirds are patients recruited consecutively from rheumatologists’ practices, 90% of which are private, and 2) the remainder are from registries sponsored by pharmaceutical companies. Data are collected from participants every 6 months by mail or online survey. For the present study, surveys conducted between January 2002 and July 2005 included detailed questions about employment. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

Subjects

To ensure complete followup data, we selected NDB participants who supplied employment and other data consecutively over an 18-month span (4 surveys) within the 2002–2005 time period. The first survey in a subject’s 18-month period was the baseline survey, and the next 3 surveys were the first, second, and third followup surveys. All subjects were employed at baseline and were age <64 years at first followup and therefore under age 65 years, the normal age for retirement, at the last followup.

Design

Because cohort studies are exposed to confounding from extraneous factors (14), we used a nested, matched, case– control design, in addition to analytic methods, to address possible confounding. The time of subjects’ baseline survey varied over a 2-year period, and such variation could affect employment outcomes because of external changes such as the unemployment rate. In addition, while the majority of subjects (>90%) supplied data in all 3 followup surveys, we included subjects who missed the second followup survey and reported the same employment status at first and third followup (not employed or employed in both surveys) under the assumption that their employment status was the same in all followup surveys. To ensure equal distribution of these factors, cases and controls were matched on time of baseline survey and completeness of data supplied.

Variables

Outcome variables

The outcome was work disability, which was consistent not-employed status across the followup surveys, beginning with the first followup. Because subjects were employed at baseline, this represented loss of employment over 1–1.5 years. Case subjects were not employed in the followup surveys, and controls remained employed in all surveys.

We used 2 different work disability outcomes, each representing case status. The primary outcome was any employment loss. Because subjects could have stopped working for reasons entirely unrelated to RA, and use of anti-TNF agents would most likely affect RA-related work disability, we included a secondary work disability outcome: RA-attributable employment loss. In the NDB survey, subjects were asked, “Did you ever retire early or permanently stop working because of your arthritis or other pain problem?” Among primary work disability outcome cases, we assessed whether subjects gave a positive response to this question in any of the followup surveys; subjects who did were considered RA-attributable work disability cases. Subjects who were not employed but did not attribute this to RA were not included in analyses with this outcome.

Employment was defined as any amount of employment work, which was assessed with 2 questions. First, subjects were queried about whether their “main form of work” was “unemployed, paid work, retired, housework, student, or disabled.” Second, subjects were asked whether they performed any amount of employment work. We combined the responses to these questions so that subjects were employed if they reported paid work as their main form of work or, when their main form of work was unemployed, retired, housework, student, or disabled, if they simultaneously reported performing some amount of employment work. Employed subjects also had to report weekly or monthly work hours. This definition is similar to that used in the US Current Population Survey (15).

Predictor variables

The exposure of interest was use of an anti-TNF agent (infliximab, etanercept, or adalimumab) at baseline. We conducted a literature search and considered risk factors that could confound the effect of anti-TNF agent use on the work disability outcomes. These risk factors fell into 4 categories: demographic, RA disease, general health, and work characteristics (16,17).

The demographic variables were age, sex, race, marital status, educational attainment, and personal income from employment. RA disease factors were disease duration in years, functional limitation (assessed by the Health Assessment Questionnaire [HAQ] disability index) (18), pain, fatigue, disease activity joint count, and RA global severity. The latter was assessed by the question, “Considering all the ways your illness affects you, rate how you are doing on the following (0 –10) scale.” General health risk factors were overall health status, number of comorbidities, and depression. Work factors were the number of hours worked per week, degree of commuting difficulty, the physical demand of subjects’ jobs, self-employment, type of job (professional or managerial versus other), use of job-related health insurance or retirement benefits, stressful job, coworker and supervisor support (19), and work preference (full time, part time, or not to work) (20).

Statistical analyses

Matched case– control analyses (main analyses)

The main method of analysis was conditional logistic regression to examine the role of anti-TNF agents in predicting work disability at followup, i.e., case–control status. The first step was to conduct crude analyses for each of the 2 work disability outcomes: the primary outcome of any employment loss and the secondary outcome of RA-attributed employment loss.

The second step was to examine the relationship between anti-TNF agent use and the risk of work disability, adjusting for possible confounding factors. Using analysis of variance for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables, we compared the characteristics of the participants by work disability status and anti-TNF agent use status. In the multivariable conditional logistic models, we adjusted for other variables on which cases and controls, or anti-TNF users and nonusers, differed significantly, or that were considered important, while matching on time of entry to the cohort and completeness of outcome data. The other factors were age, sex, education, personal income, RA duration, functional limitation, RA global severity, hours worked per week, professional or managerial versus other job types, self-employment, stressful job, and work preference.

Stratified analyses

To further assess whether the association between anti-TNF agent use and risk of work disability is modified by particular risk factors, we performed matched conditional logistic analyses stratified by such factors. The factors were those included in the main multivariable conditional logistic regression models; the analyses were adjusted for the other factors, including the stratified factor. Within each stratum, we examined the relationship between anti-TNF use and risk of work disability. If the result indicating the effect of anti-TNF use varied according to the stratified variable, we added an interaction term into the regression model to test if such an interaction term was statistically significant. A 2-sided P value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Variable stratification was conducted as follows. Older age has been found to be a significant risk factor for RA work disability in all studies (16,17) and may, to some extent, represent retirement that is unrelated to RA. We therefore stratified age by ≤59 years and >59 years because people can begin to withdraw personal retirement funds at age 59.5 years. We were particularly interested in the effect of anti-TNF agents in the younger age stratum.

Because anti-TNF agents are thought to be most effective in early disease, we wished to stratify disease duration into early and longer periods. However, there were insufficient numbers of subjects with 1–2 years of disease, therefore duration was stratified at the median, 10.9 years (10.7 years for RA-attributable employment loss). The other continuous variables were likewise stratified by their median scores, except for number of hours worked, which was stratified by full-time (≥35 hours) and part-time work. The other factors were all dichotomous.

Classification tree and random forest analyses

Although detecting possible confounding by each individual risk factor is useful, RA work disability likely stems from complex interactions among demographic, disease and health, and work characteristics. Predicting work disability without consideration of interactions among these factors, some of which, at least, cannot be foreseen, disregards the complex relationship between details of an individual’s situation and the decision to stop working. Nonparametric techniques of recursive partitioning have been suggested to detect synergistic interactions among various risk factors (21,22), and we used these techniques to examine how use of an anti-TNF agent might interact with other factors to predict work disability.

Recursive partitioning is data-driven, but internally cross-validated successive splitting of risk factors to construct a classification tree for a categorical outcome. All risk factors are examined, and the factor that gives the best split (i.e., the one that gives the best classification in the resulting subgroups) is chosen. The “best” classification tree is a tree pruned based on specific criteria that are a compromise to the complexity of the classification tree and classification error. We used the R software rpart, version 3.1–38 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) for the recursive partitioning, which was based on the work by Breiman et al (23). The primary definition of work disability was the outcome; a wider variety of risk factors than in the conditional logistic regression models was included.

We also used random forest techniques (R package randomForest; R Foundation for Statistical Computing) to determine the importance of anti-TNF agent use in predicting work disability in relation to the other risk factors (24,25). We ran a random forest procedure for each of the outcomes (any employment loss and RA-attributable employment loss).

RESULTS

Sample

A total of 272 cases were identified. Examination of strata formed by time of the baseline survey and completeness of followup data revealed that ≥3 controls were available for cases in all strata, therefore 816 controls were matched to cases in an approximately 3:1 ratio. However, 135 subjects had missing data on several work characteristic variables and were excluded. In the resulting sample of 953 subjects, 231 were cases and 722 were controls; controls were rematched ~3:1 to cases. Of the cases, 152 (66%) had RA-attributable employment loss.

The sample was predominantly middle aged (mean age 51 years), female (82%), and white (92%); nearly three-quarters (72%) had an education beyond high school. At baseline, 457 (48%) subjects had used ≥1 anti-TNF agent during the prior 6 months; of 470 reported uses, 270 (58%) used infliximab, 184 (38%) used etanercept, and 16 (4%) used adalimumab.

Cases differed from controls on many characteristics (Table 1), but equal proportions (46% versus 49%; P = 0.47) used an anti-TNF agent. The characteristics of anti-TNF agent users and nonusers were quite similar, although due to the relatively large sample size, small differences were sometimes significant (Table 2). Users were a year younger (mean age 51 years versus 52 years; P = 0.004), had shorter RA duration (mean 12 years versus 14 years; P = 0.0003), and had greater functional limitation (mean HAQ score 0.9 versus 0.7; P = 0.003).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline data of cases and controls*

| Characteristic | Cases (n = 231) | Controls (n = 722) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD years | 54.0 ± 8.1 | 50 ± 8.4† |

| Female | 85 | 81 |

| White | 94 | 92 |

| More than high school education | 63 | 75† |

| More than US median income‡ | 31 | 56† |

| RA duration, mean ± SD years | 15 ± 9.9 | 13 ± 9.4§ |

| HAQ score, mean ± SD¶ | 1.0 ± 0.7 | 0.7 ± 0.6† |

| RA global severity, mean ± SD# | 3.8 ± 2.6 | 2.7 ± 2.2† |

| Use anti-TNF agent | 46 | 49 |

| Hours worked per week, mean ± SD | 29 ± 15.6 | 37 ± 13.0† |

| Community difficulty, mean ± SD** | 4.8 ± 5.2 | 3.7 ± 4.1† |

| Self-employed | 25 | 15† |

| Professional/managerial job | 30 | 48† |

| Stressful job†† | 23 | 19 |

| Work preference | ||

| Full time | 22 | 48† |

| Part time | 45 | 41 |

| Not to work | 33 | 11 |

Values are the percentage unless otherwise indicated. RA = rheumatoid arthritis; HAQ = Health Assessment Questionnaire; anti-TNF = anti–tumor necrosis factor.

P < 0.001.

Personal income from employment.

P ≤ 0.05.

Measure of functional limitation (0 –3 scale, 3 = greater limitation).

Status considering all effects of RA illness (0 –10 scale; 0 = very well, 10 = poor).

0 –10 scale, 10 = reater difficulty.

High-demand, low-control job.

Table 2.

Comparison of anti–tumor necrosis factor agent users and nonusers at baseline*

| Characteristic | Users (n = 457) | Nonusers (n = 496) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD years | 51 ± 9 | 52 ± 8† |

| Female | 81 | 83 |

| White | 93 | 92 |

| More than high school education | 71 | 73 |

| More than US median income‡ | 49 | 45 |

| RA duration, mean ± SD years | 12 ± 9 | 14 ± 10† |

| HAQ score, mean ± SD§ | 0.9 ± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.6† |

| RA global severity, mean ± SD¶ | 2.8 ± 2.1 | 3.1 ± 2.5 |

| Hours worked per week, mean ± SD | 34 ± 14 | 35 ± 15 |

| Community difficulty, mean ± SD# | 4.1 ± 4.4 | 3.8 ± 4.5 |

| Self-employed | 18 | 17 |

| Professional/managerial job | 44 | 42 |

| Stressful job** | 19 | 21 |

| Work preference | ||

| Full time | 46 | 39 |

| Part time | 40 | 44 |

| Not to work | 14 | 18 |

Values are the percentage unless otherwise indicated. RA = rheumatoid arthritis; HAQ = Health Assessment Questionnaire.

P ≤0.01.

Personal income from employment.

Measure of functional limitation (0 –3 scale, 3 = greater limitation).

Status considering all effects of RA illness (0 –10 scale; 0 = very well, 10 = poor).

0 –10 scale, 10 = greater difficulty.

High-demand, low-control job.

Matched case–control analyses (main analyses)

Anti-TNF use did not predict employment status at followup. The crude odds ratio (OR) for anti-TNF use in the model for the primary work disability outcome was 0.8 (n = 953) (Table 3). When adjusted for the other risk factors, the OR was 1.1 (95% confidence interval [95% CI] 0.7–1.6; n = 780). The OR for anti-TNF use in the adjusted model for the secondary outcome, RA-attributable work disability, was 0.9 (95% CI 0.5–1.5; n = 720).

Table 3.

Prediction of work disability by use of anti-TNF agents*

| Work disability outcome | Anti-TNF use | No. of cases | No. of controls | Crude OR | Adjusted OR (95% CI)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any employment loss | Yes | 106 | 351 | 0.8 | 1.1 (0.7–1.6) |

| No | 125 | 371 | 1.0 | 1.0 (reference) | |

| RA-attributable employment loss | Yes | 61 | 300 | 0.9 (0.5–1.5) | |

| No | 63 | 296 | 1.0 (reference) |

Anti-TNF = anti–tumor necrosis factor; OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; RA = rheumatoid arthritis.

Adjusted for age, sex, education, personal income, RA duration, functional limitation, RA global severity, hours worked per week, type of job, self-employment, stressful job, and work preference.

Stratified analyses

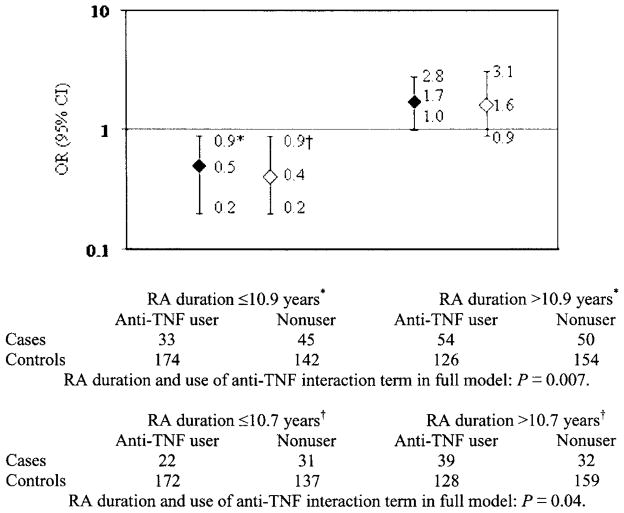

In the stratified analyses, anti-TNF use did protect against work disability among subjects with shorter disease duration (Figure 1). Among 394 subjects with disease duration <11 years (≤10.9 years), the OR for anti-TNF use with the primary work disability outcome was 0.5 (95% CI 0.1– 0.9). The converse was true among 384 subjects with RA duration ≥11 years, i.e., anti-TNF use predicted work disability (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.0 –2.8). The interaction term between disease duration and anti-TNF use was significant (P = 0.007). Findings were similar among subjects with RA-attributable work disability. Among 362 subjects with disease duration <11 years, use of an anti-TNF agent protected against work disability (OR 0.4, 95% CI 0.2– 0.9) and predicted work disability among 358 subjects with disease duration ≥11 years (OR 1.6, 95% CI 0.9 –3.1); the interaction term was also significant (P = 0.04). These analyses were adjusted for the same factors as the main analyses, including RA duration. The age and disease characteristics of users and nonusers in both RA duration subgroups were similar; among those with an RA duration ≥11 years, users were significantly younger, but only by 1.5 years (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Anti–tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) use as a predictor of work disability, stratified by rheumatoid arthritis (RA) duration. * Any employment loss work disability definition. † RA-attributed employment loss work disability definition. OR = odds ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval. Solid diamonds = any employment loss; open diamonds = employment loss attributed to RA.

Table 4.

Comparison of anti–tumor necrosis factor users and nonusers in the shorter and longer RA duration subgroups*

| RA duration ≤10.9 years (n = 394)†

|

RA duration >10.9 years (n = 384)†

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Users | Nonusers | Users | Nonusers | |

| Age, years | 51 | 51 | 52 | 53‡ |

| HAQ score§ | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 0.8 |

| RA global severity score¶ | 2.7 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

Values are the mean. RA = rheumatoid arthritis; HAQ = Health Assessment Questionnaire.

10.9 = median years.

P < 0.05.

Measure of functional limitation (0 –3 scale, 0 = no limitation).

Status considering all effects of RA illness (0 –10 scale; 0 = very well, 10 = poor).

Anti-TNF use did not predict work disability in any of the other stratified risk factor analyses. For example, among 649 subjects age ≤59 years, the OR for anti-TNF use was 1.1 (95% CI 0.7–1.7), whereas among 131 subjects age > 59 years, the OR was 1.0 (95% CI 0.4 –2.4).

Classification tree and random forest analyses

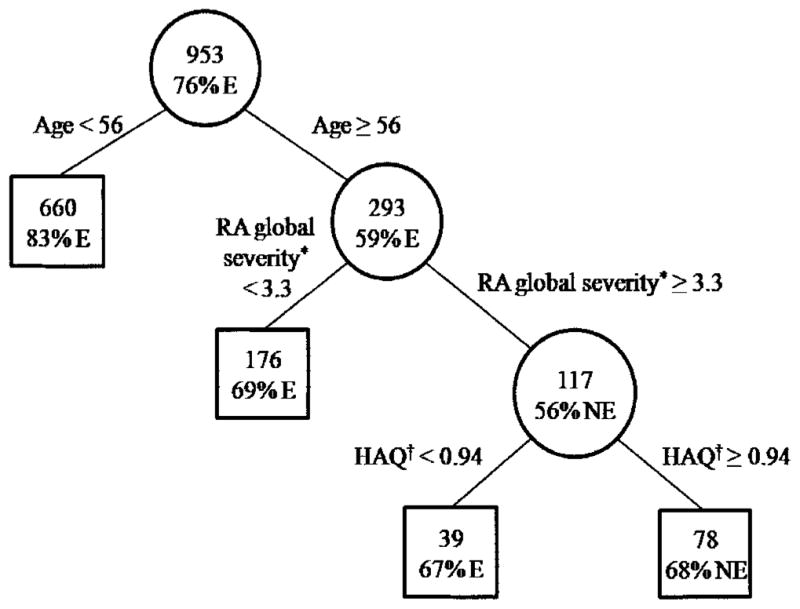

The classification tree with the least relative error produced splits on 3 risk factors and had 4 terminal nodes (Figure 2). The risk factors were age, RA global severity, and functional limitation. Subjects younger than age 56 years were more likely to be employed than older subjects; no other risk factors predicted employment loss among younger subjects. More severe disease, especially the combination of greater global effect of RA and greater functional limitation, predicted loss of employment among older subjects. In a full tree with relative error greater than the accepted standard, anti-TNF use protected against employment loss only among a small number of subjects with a complicated mix of other risk factors (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Classification tree of employment status at followup. Boxes are final nodes. The top number in each circle or box is the number of subjects. The percentage is the dominant proportion. * Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) global severity = status considering all RA effects; higher score = poorer status. † Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) measure of functional limitation: higher score = greater limitation. E = employed; NE = not employed.

In the random forest analysis, anti-TNF agent use was the 16th most important factor of the 20 variables included. The average random forest classification error rate was 22.3%, representing good, but not excellent, predictive accuracy. In an analysis using the RA-attributable work disability outcome, functional limitation replaced age as the highest-ranked factor, but anti-TNF agent use was still ranked as the 16th most important factor. There was less classification error in this analysis (15.5%).

DISCUSSION

In the main multivariable regression analyses, we found that use of an anti-TNF agent did not protect against work disability, whether defined as any loss of employment or loss attributed to RA. Our data are from an observational cohort, and determining true treatment effects using such data is challenging. To further address possible confounding, we conducted stratified analyses on the risk factors included in the multivariable analyses, where we found a protective effect of anti-TNF use among subjects with a shorter duration of RA, i.e., <11 years. This effect was found in subjects who attributed their employment loss to RA and those with any employment loss, and makes clinical sense because anti-TNF agents are especially effective in early disease. Nevertheless, the finding must be interpreted with caution. A number of factors other than RA disease likely influence patients’ decisions to stop working prematurely. In nonparametric analysis assessing interactions among variables, use of anti-TNF agents was protective for only a small number of subjects. The elimination of matching in recursive partitioning analyses is a possible explanation for the discrepant findings.

The results of our analyses are similar to those found by Wolfe et al (26) and Smolen et al (10) and are partly different from the findings of Yelin et al (11). Wolfe et al used more narrow definitions of work disability, i.e., self-reported disability (as main work status) or receipt of Social Security disability pension, rather than employment status at followup, the definition used in our study and the other 2 studies. Samples in our study and those by Smolen et al and Yelin et al were similar in that they were limited to subjects age ≤65 years. However, the samples differed in disease duration, with all subjects in the study by Smolen et al having early disease (≤3 years), all subjects in the study by Yelin et al having disease durations >3 years, and subjects in our sample having disease durations both shorter and longer than 3 years. Duration of anti-TNF agent use varied to a limited extent among the studies: 1 year in the Smolen et al study, >1 year but probably <5 years in the Yelin et al study, and unknown duration in our study, although unlikely to be long, given the amount of time the agents have been on the market. Study design differed: the Smolen et al study was a randomized trial, the main analysis in the Yelin et al study compared subjects from anti-TNF trials with those in an observational cohort, and our study used subjects from the same observational cohort. In a secondary analysis in the Yelin et al study, no significant difference in employment status was found among all subjects using etanercept, whether they were from a trial or the observational cohort, compared with nonusers.

Reduced work disability resulting from anti-TNF agents is expected given their substantial effect on symptoms, functional limitation, and radiologic progression (6,9), so why did our study not find this effect across all subjects? One possibility is that because anti-TNF agents are most effective very early in the course of RA, a protective effect against work disability might occur only in subjects with short disease duration. We did not have adequate numbers of subjects to examine effect in those with 1–2 or 1–5 years of disease duration; however, Smolen et al (10) did not find an effect on employment status in their sample of subjects with early RA. It is possible that work cessation early in the course of disease is difficult to eliminate. An excess incidence of work disability in the first year or 2 of disease has been found in many studies, at times occurring even prior to treatment initiation (16,17,27), and could be interpreted as the effect of simply having RA on individuals close to stopping work before onset of the disease. Puolakka et al, however, found that work disability was reduced in subjects with early RA whose disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) treatment induced clinical remission (28).

The effect of anti-TNF agents on RA work disability may become evident as more patients are treated in the very early disease period and for longer periods of time (6,29). Although subjects in the Smolen et al study (10) had short durations of RA, they were followed for only 1 year (54 weeks). Some of our subjects likely used these agents longer than a year, but in most cases their use would not have been initiated early in the course of disease.

We considered the possibility that anti-TNF agents do not have unique efficacy for work disability; various DMARD combination therapies are effective (30). This was explored in further conditional logistic regression analyses with variables representing use of methotrexate alone, use of an anti-TNF agent alone, and combined use of an anti-TNF agent and methotrexate. None of these treatment variables predicted employment status at followup (data not shown).

Last, although the anti-TNF agents are quite effective in treating RA, the disease does not go into remission in most patients (31), in part perhaps because patients treated with these agents have more severe disease (32). Three studies suggest that remission, or at least minimal disease activity, is required to have a substantial impact on work disability. Among patients treated with synthetic DMARDs early in the course of disease, permanent work disability was substantially reduced only among those who were in clinical remission (28). In a recent study by Wolfe et al, subjects whose disease was in a minimal disease activity state had a 10-fold reduction in work disability, as defined by receipt of Social Security disability pension (32). And in a study of subjects with Crohn’s disease treated with infliximab, a significantly higher proportion of subjects whose disease went into remission returned to work than those whose disease did not achieve remission (33).

One strength of our study was use of data from a US national cohort of subjects with rheumatologist-diagnosed RA and detailed assessment of anti-TNF agent use and employment information. Second, although confounding is a problem in using observational cohort data for the study of treatment effects, we used a number of recommended strategies to address possible confounding (14). These strategies included subject matching, literature search for confounding factors, regression analyses that included these factors, and analyses stratified by each of the factors. In addition, we used nonparametric analytic procedures to assess synergistic relationships among risk factors.

A limitation of our sample is that it was not population based. Subjects were more often of white race and had a higher educational attainment than the US population, and both characteristics offer employment advantages. Perhaps use of anti-TNF agents is more effective in reducing work disability among persons with fewer employment advantages, for example, those with physically demanding jobs. In addition, the NDB cohort may not be representative of RA patients in that approximately one-third (32% of our sample) are from pharmaceutical registries. Registry subjects in our sample differed significantly from nonregistry subjects in that they were more likely to be male (23% versus 16%), had shorter disease duration (mean 12 years versus 14 years), had greater functional limitation (mean HAQ score 0.9 versus 0.8), and were less likely to have a professional or managerial job (38% versus 46%). However, there was no difference in the proportion of registry subjects among our study cases and controls (34% versus 31%; P = 0.5).

In addition, our sample was a subgroup of the full NDB cohort. Twelve percent of the NDB cohort completed short questionnaires containing no questions about employment and therefore were not eligible for our sample. These participants were more likely to be recruited from the pharmaceutical registries (45% versus 35%). They differed from participants who completed full questionnaires in that they were less likely to be white or married and had lower educational attainment. NDB participants who supplied data on an irregular basis were also not eligible for our sample. A total of 3,680 participants age <63.5 years and employed at their first observation, but not eligible for our sample, were very similar to 1,088 eligible participants. However, due to large sample sizes, ineligible participants were significantly younger (mean age 50 years versus 51 years), were more likely to be male (22% versus 18%) or nonwhite (10% versus 8%), had shorter disease duration (mean 12 years versus 13 years), and worked more hours per week (mean 38 versus 35). They were just as likely to have been recruited via a pharmaceutical registry.

In summary, we did not find that anti-TNF agent use protected against work disability in the main analyses. In stratified analyses, we did find a protective effect of their use among subjects with shorter (<11 years) RA duration. This finding makes clinical sense because the agents are known to be particularly effective in early disease. However, in nonparametric analyses, the RA global severity and functional limitation disease factors played much more prominent roles in predicting work disability than anti-TNF agent use.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, NIH, Bethesda, Maryland (grant P60-AR-47785).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dr. Allaire had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study design. Allaire, Wolfe, LaValley.

Acquisition of data. Allaire, Wolfe.

Analysis and interpretation of data. Allaire, Wolfe, Niu, Yuqing Zhang, Bin Zhang, LaValley.

Manuscript preparation. Allaire, Yuqing Zhang, Bin Zhang, LaValley.

Statistical analysis. Allaire, Niu, Yuqing Zhang, Bin Zhang, LaValley.

References

- 1.Yelin E. The costs of rheumatoid arthritis: absolute, incremental, and marginal estimates. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1996;44:47–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pugner KM, Scott DI, Holmes JW, Hieke K. The costs of rheumatoid arthritis: an international long-term view. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2000;29:305–20. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(00)80017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merkesdal S, Ruof J, Schoffski O, Bernitt K, Zeidler H, Mau W. Indirect medical costs in early rheumatoid arthritis: composition of and changes in indirect costs within the first three years of disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44:528–34. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200103)44:3<528::AID-ANR100>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hallert E, Husberg M, Skogh T. Costs and course of disease and function in early rheumatoid arthritis: a 3-year follow-up (the Swedish TIRA project) Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006;45:325–31. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jacobsson LT, Lindroth Y, Marsal L, Juran E, Bergstrom U, Kobelt G. Rheumatoid arthritis: what does it cost and what factors are driving those costs? Results of a survey in a community-derived population in Malmö. Sweden Scand J Rheumatol. 2007;36:179– 83. doi: 10.1080/03009740601089580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verstappen SM, Jacobs JW, Hyrich KL. Effect of anti-tumor necrosis factor on work disability. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:2126– 8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kobelt G, Lindgren P, Singh A, Klareskog L. Cost effectiveness of etanercept (Enbrel) in combination with methotrexate in the treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis based on the TEMPO trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64:1174–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.2004.032789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laas K, Peltomaa R, Kautiainen H, Puolakka K, Leirisalo-Repo M. Pharmacoeconomic study of patients with chronic inflammatory joint disease before and during infliximab treatment. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:924– 8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.041574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weaver AL. The impact of new biologicals in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43(Suppl 3):iii17–23. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smolen JS, Han C, van der Heijde D, Emery P, Bathon JM, Keystone E, et al. Infliximab treatment maintains employability in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:716–22. doi: 10.1002/art.21661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yelin E, Trupin L, Katz P, Lubeck D, Rush S, Wanke L. Association between etanercept use and employment outcomes among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3046–54. doi: 10.1002/art.11285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farahani P, Levine M, Gaebel K, Wang EC, Khalidi N. Community-based evaluation of etanercept in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:665–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, Bansback N, Guh D, Li X, Nosyk B, Marra CA, et al. Short-term impact of adalimumab on productivity outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis [abstract] Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56 (Suppl 9):S89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klein-Geltink JE, Rochon PA, Dyer S, Laxer M, Anderson GM. Readers should systematically assess methods used to identify, measure and analyze confounding in observational cohort studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:766–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.US Census Bureau. Basic Monthly Survey CPS Questionnaire. 1997 URL: http://www.bls.census.gov/cps/bqestair.htm.

- 16.Verstappen SM, Bijlsma JW, Verkleij H, Buskens E, Blaauw AA, ter Borg EJ, et al. on behalf of the Utrecht Rheumatoid Arthritis Cohort Study Group. Overview of work disability in rheumatoid arthritis patients as observed in cross-sectional and longitudinal surveys [review] Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:488–97. doi: 10.1002/art.20419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allaire SH. Update on work disability in rheumatic diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2001;13:93– 8. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200103000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fries JF, Spitz PW, Young DY. The dimensions of health outcomes: the Health Assessment Questionnaire, disability and pain scales. J Rheumatol. 1982;9:789–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lacaille D, Sheps S, Spinelli JJ, Chalmers A, Esdaile JM. Identification of modifiable work-related factors that influence the risk of work disability in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51:843–52. doi: 10.1002/art.20690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reisine S, McQuillan J, Fifield J. Predictors of work disability in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a five-year followup. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:1630–7. doi: 10.1002/art.1780381115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cook EF, Goldman L. Empiric comparison of multivariate analytic techniques: advantages and disadvantages of recursive partitioning analysis [published erratum appears in J Chronic Dis 1986;39:157] J Chronic Dis. 1984;37:721–31. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(84)90041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bloch DA, Moses LE, Michel BA. Statistical approaches to classification: methods for developing classification and other criteria rules. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1137– 44. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breiman L, Friedman JH, Olshen RA, Stone CJ. Classification and regression trees. Monterey (CA): Wadsworth; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Breiman L. Manual on setting up, using, and understanding random forests V3.1. 2002 URL: http://oz.berkeley.edu/users/breiman/Using_random_forests_V3.1.pdf.

- 26.Wolfe F, Allaire S, Michaud K. The prevalence and incidence of work disability in rheumatoid arthritis, and the effect of anti-tumor necrosis factor on work disability. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:2211–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eberhardt K, Larsson BM, Nived K, Lindqvist E. Work disability in rheumatoid arthritis: development over 15 years and evaluation of predictive factors over time. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:481–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puolakka K, Kautiainen H, Mottonen T, Hannonen P, Korpela M, Hakala M, et al. for the FIN-RACo Trial Group. Early suppression of disease activity is essential for maintenance of work capacity in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: five-year experience from the FIN-RACo trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:36– 41. doi: 10.1002/art.20716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wakefield RJ, Freeston JE, Hensor EM, Bryer D, Quinn MA, Emery P. Delay in imaging versus clinical response: a rationale for prolonged treatment with anti–tumor necrosis factor medication in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:1564– 67. doi: 10.1002/art.23097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Donahue KE, Gartlehner G, Jonas DE, Lux LJ, Thieda P, Jonas BL, et al. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness and harms of disease-modifying medications for rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148:124–34. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-2-200801150-00192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felson DT, Zhang B, Siegel JN. Trials in rheumatoid arthritis: choosing the right outcome measure when minimal disease is achievable. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:580–3. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.079632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolfe F, Rasker JJ, Boers M, Wells GA, Michaud K. Minimal disease activity, remission, and the long-term outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:935– 42. doi: 10.1002/art.22895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lichtenstein GR, Yan S, Bala M, Hanauer S. Remission in patients with Crohn’s disease is associated with improvement in employment and quality of life and a decrease in hospitalizations and surgeries. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:91– 6. doi: 10.1046/j.1572-0241.2003.04010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]