Abstract

Accumulating evidence suggests that African American men and women experience unique challenges in developing and maintaining stable, satisfying romantic relationships. Extant studies have linked relationship quality among African American couples to contemporaneous risk factors such as economic hardship and racial discrimination. Little research, however, has examined the contextual and intrapersonal processes in late childhood and adolescence that influence romantic relationship health among African American adults. We investigated competence-promoting parenting practices and exposure to community-related stressors in late childhood, and negative relational schemas in adolescence, as predictors of young adult romantic relationship health. Participants were 318 African American young adults (59.4% female) who had provided data at four time points from ages 10–22 years. Structural equation modeling indicated that exposure to community-related stressors and low levels of competence-promoting parenting contributed to negative relational schemas, which were proximal predictors of young adult relationship health. Relational schemas mediated the associations of competence-promoting parenting practices and exposure to community stressors in late childhood with romantic relationship health during young adulthood. Results suggest that enhancing caregiving practices, limiting youths’ exposure to community stressors, and modifying relational schemas are important processes to be targeted for interventions designed to enhance African American adults’ romantic relationships.

Keywords: African American, community stress, family, romantic relationship, schema, young adult

Introduction

Accumulating evidence indicates that young African American adults experience significant challenges in developing and maintaining stable, satisfying romantic relationships (Burton & Tucker 2009; Dixon 2009; Fields 2004). Studies indicate that, compared with other racial/ethnic groups, romantic relationships among African Americans in general and young adults in particular are characterized by considerable conflict, instability, and dissatisfaction (Anderson, 1999; Kurdek, 2008; Wilson, 2003). Their dramatically declining marriage rates during the past three decades provide further evidence of the disproportionate relationship challenges that African Americans experience. In 1986, 56% of African American women 25 to 29 years of age reported having been married in their lifetimes compared with 31% in 2009 (Kreider & Ellis 2011). Many African Americans who do marry experience high divorce rates (Fields & Casper, 2001; Sweeney & Phillips, 2004) and low marital quality (Oggins, Veroff, & Leber, 1993), underscoring the importance of research on the factors that contribute to romantic relationship difficulties among African American couples.

To date, research on the factors associated with African Americans’ romantic relationship quality has focused primarily on contemporaneous contextual factors that are negatively associated with relationship health (Chapman, 2007). Indicators of poverty, including unemployment and perceived financial instability, are associated with the quality and long-term stability of African American couples’ romantic relationships (Conger et al., 2002; Cutrona, Russell, Burzette, Wesner, & Bryant, 2011). Cutrona and colleagues (2011) reported that income level and financial strain predicted relationship quality in a sample of married and cohabitating African American couples living in nonurban communities. Although the effect of financial hardship on romantic relationships is similar across racial and ethnic groups, African Americans are disproportionately affected by financial hardship (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor, & Smith, 2009). Economic hardship also covaries extensively with residence in disadvantaged neighborhoods, which negatively affects relationship satisfaction and stability (Cutrona et al., 2003). Racial discrimination is a common experience among African Americans that appears to take a toll on couple’s relationship quality. Studies link racial discrimination with reduced marital satisfaction and relationship quality (Riina & McHale, 2010); the combination of racial discrimination and economic distress has been found to be particularly challenging for African American couples (Lincoln & Chae, 2010).

Although investigations of the influence of contemporaneous contextual factors on African Americans’ relationship quality have identified important risk factors, this research does not include consideration of childhood and adolescent experiences that could be pivotal in determining how individuals will experience later romantic relationships. The majority of studies on romantic relationships among youth and young adults, in fact, have been conducted with Caucasian samples; thus, little is known about the possible, prospective influence of community and family processes on African Americans’ romantic relationships. Studies with Caucasians suggest that family and community contextual processes experienced in late childhood and adolescence affect adults’ likelihood of forming satisfying, committed relationships (Karney, Beckett, Collins, & Shaw, 2007). Significantly, contextual factors experienced in childhood and adolescence are thought to contribute to internal working models, or schemas (Simons et al., 2006), of relationships, which may account for the enduring effects of preadolescent experiences into adulthood. Few studies, however, have investigated the pathways from contextual influences to relationship schemas among African Americans; the present study addresses this issue.

Ecological and attachment perspectives on the development of romantic relationship behavior (Collins, Welsh, & Furman 2009) informed our hypotheses regarding the late childhood and adolescent factors that influence African Americans’ relationships in young adulthood. Consistent with an ecological perspective on youth development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998) and with research on Caucasian samples, we view family and community environments as interaction contexts that shape not only youths’ immediate behavior but also their future relationships during later stages of development. Attachment theories suggest that experiences in late childhood, particularly with family relationships, will be internalized as relationship schemas (Dinero, Conger, Shaver, Widaman, & Larsen-Rife, 2008) that carry forward to influence romantic relationship health in young adulthood and beyond. Although family environments are thought to be particularly influential, experiences in community environments, particularly in stressful or disadvantaged contexts, have been hypothesized to affect relational schemas as well (Simons et al., 2006). In the following sections, we review evidence for the roles of family and community environments and relationship schemas as processes that forecast romantic relationship health among African American young adults.

Preadolescent Family and Community Environments and Romantic Relationships

Studies conducted primarily with Caucasian samples indicate that family factors forecast youths’ behavior in romantic relationships (Collins et al., 2009). Using a prospective design, Conger and colleagues (2000) examined the association between family processes in late childhood and romantic relationship quality in adulthood. Among their sample of families in Iowa, youth who experienced warm and supportive relationships with their caregivers during late childhood were more likely to be satisfied with the romantic relationships they formed in their late twenties. In a study with adolescents, Furman et al. (2002) found that supportive parent-youth relationships were associated with youth-reported support in romantic relationships. In other research examining the influences of the family of origin on romantic relationship dynamics, warmth and sensitivity in family interactions during adolescence predicted nurturing and supportive interactions with romantic partners during early adulthood (Dinero et al., 2008). Black and Schutte (2006) found that young adults who reported warm and loving relationships with their caregivers during late childhood also reported substantial warmth and cooperative communication with their romantic partners. Combined, these studies suggest that parenting practices in late childhood may be a potent factor that shapes young people’s participation in romantic relationships as adults.

To our knowledge, no prospective research has investigated the potential effects of parenting practices in late childhood on African Americans’ romantic relationships. Brody and colleagues (Brody, Kim, Murry, & Brown, 2004; Brody, Murry, et al., 2004) have identified a cluster of parenting practices that enhance African American youths’ development. African American youth who demonstrate psychosocial competence despite difficult environments experience diligent monitoring of their behavior as part of close, warm parent-youth relationships. As youth become adolescents, parents also use inductive rearing practices, soliciting youths’ opinions about matters that involve the youth rather than unilaterally imposing rules. Inductive parenting interactions have been linked to protective sexual behavior in romantic relationships (Kogan et al., 2012; Kogan, Yu, Brody, & Allen, 2012). These competence-promoting parenting practices occur together in the families of resilient youth. Although competence-promoting parenting practices have not been investigated as precursors of African Americans’ healthy romantic relationships in young adulthood, they are linked to African American youths’ development of prosocial behavior, self-regulatory processes, and conventional norms and attitudes (Brody, Dorsey, Forehand, & Armistead, 2002; Brody et al., 2001). These factors, in turn, have been linked to romantic relationship health (Florsheim & Moore, 2008; Ciarocco, Echevarria, & Lewandowski, 2012). We thus extend the present research base by investigating youth-reported parental monitoring, parent-child warmth, and inductive interactions as precursors to romantic relationship well-being in young adulthood.

Consistent with an ecological perspective, we expect that exposure to community-related stressors during late childhood will shape the ways in which African Americans view and participate in romantic relationships. Studies of African American youth reveal that exposure to community-related stressors has a profound influence on several developmental outcomes, including educational attainment, externalizing problems, and substance use (Brody et al., 2001; Lee, 2012; McNulty & Bellair, 2003). Of particular significance, African Americans are more likely than their peers from other racial/ethnic groups to experience high rates of community-related stressors that can compromise development (Thomas, Woodburn, Thompson & Leff, 2011). In this research, we focused on three of these stressors: community crime, personal victimization, and racial discrimination.

Prevalent crime in a community can undermine youths’ prosocial development (Jones, 2007; McKelvey et al., 2011). Burton and Tucker (2009) suggested that disadvantaged, high-crime neighborhoods also can restrict involvement in healthy romantic relationships. Such contexts are hypothesized to foster uncertainty about the future, which can discourage commitment and foster distrust in close relationships (Anderson, 1999; Burton & Tucker, 2009; Simons, et al., 2012). The personal experience of victimization has been found to undermine mental health and relationship functioning (Kelly, Schwartz, Gorman, & Nakamoto, 2008; Scarpa & Haden, 2006). General community deviance and personal victimization both have been found to facilitate the development of negative emotions and foster a sense of loss of control over one’s life (Sieger, Rojas-Vilches, McKinney, & Renk, 2004). This may result in a heightened level of stress that can influence the behaviors that individuals direct toward their romantic partners (Beach, Smith, & Fincham 1994; Wickrama, Bryant, & Wickrama 2010).

Racial discrimination is a common stressor for African Americans, one that research indicates negatively influences adults’ romantic relationships (Bryant et al. 2010). Discrimination can be overt, such as clearly race-based hostile comments, as well as covert. Covert discrimination occurs when a person is treated unfairly based on race, but the situation is ambiguous in terms of the reason for unfair treatment. For example, a minority individual may be more carefully scrutinized in a store as a potential shoplifter (Deitch et al., 2003). Studies suggest that both forms of discrimination influence relationships by inducing negative emotions and fostering a state of vigilance arising from the anticipation of future unfair treatment (Boyd-Franklin 2003). As a result, individuals may adopt a generally defensive orientation (Simons et al., 2006) as a means of self-protection and survival. Experiences with racial discrimination, which become common among African American youth beginning in late childhood (Brody et al., 2006), have been linked to African American adolescents’ mental health (Brody, et al 2006; Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006), involvement in delinquent and aggressive behaviors (Simons et al. 2006), and involvement in risk behaviors such as substance use (Brody, Kogan, & Chen, 2012) and risky sex (Kogan et al., 2010). The extent to which discrimination in late childhood affects African Americans’ romantic relationship health in adulthood has not been studied. Consistent with studies indicating that discrimination is associated negatively with relationship health among African American adults, we expect experiences with discrimination in late childhood to be associated negatively with relationship health in young adulthood.

In the present study, we examine the accumulation of exposure to community crime, victimization, and racial discrimination over a 2-year period during late childhood as a precursor to romantic relationship health. Cumulative models of exposure to stress emphasize the numbers of risks experienced. Although any particular risk has limited value in predicting child development, the experience of multiple risks contributes dramatically to youths’ problem behavior and success in school (Ackerman, Brown, & Izard, 2004; Felix Ortiz & Newcomb, 1999; Gutman, Sameroff, & Eccles, 2002). We expect that the accumulation of community stressors in late childhood and early adolescence will shape young adult behavior in romantic relationships.

Relational Schemas and African Americans’ Romantic Relationship Health

Relational schemas are cognitive structures that represent patterns of relating within interpersonal contexts (Baldwin 1992). Developed in response to one’s history of interpersonal interactions with important others, relational schemas help individuals to define situations more efficiently by drawing attention to salient cues in the social environment, goals associated with response options, and consequences associated with particular responses (Baldwin 1992; Crick & Dodge 1994). Interactions in family environments are thought to be particularly influential in the development of adults’ processing of information about their current relationships. For example, Homer et al. (2007) found that negative family experiences in childhood were linked to adults’ mistrust of their romantic partners’ motives. Simons et al. (2012) found that youth who experienced harsh parenting during late childhood also reported cynical and hostile views of relationships in general. These studies suggest potential roles for relationship schemas characterized by hostile views of relationships and insecure attachment styles in mediating the effects of family environments on romantic relationship health.

The influence of community-related stressors on relational schemas has been less well studied. As noted previously, experiences with community-related stressors can induce a sense of mistrust in close relationships. Researchers have speculated that uncertainty about the future and the potential for losing a loved one due to chaotic living situations contribute generally to negative relationship outlooks (Burton & Tucker, 2009). Simons (2012) reported that experiences with community deviance contributed to hostile and cynical attitudes toward romantic relationships in adolescence. We thus expect African Americans’ exposure to community-related stressors to forecast relationships schemas characterized by hostile and cynical views of relationships and avoidant attachments styles.

Gender and Young Adults’ Romantic Relationship Health

Prior research indicates that gender is an important consideration when investigating contextual and intrapersonal influences on romantic relationships (Miller, Gorman-Smith, Sullivan, Orpinas, & Simon, 2009). In general, men tend to be more satisfied in romantic relationships than are women; it is not clear, however, if this is true for African Americans (Bryant, Taylor, Lincoln, Chatters, & Jackson, 2008). Studies also reveal that male and female youth differ in the extent to which family relationships and community-related stressors affect their behavior. For example, among African American adolescents, discrimination has been found to exert a greater effect on behavior problems among male youth than female youth (Brody et al. 2006). Conversely, early experiences with protective family processes have been found to have a stronger impact on academic performance among female youth than male youth (Kogan et al. 2010). Accordingly, we addressed gender in two ways in our investigation. First, gender was controlled to test a general model of relationship health. Second, a series of multigroup analyses was conducted contrasting models for male and female youth. These analyses allowed us to examine the possibility that the influence of community and family relationships varied by gender in this African American sample.

The Present Study

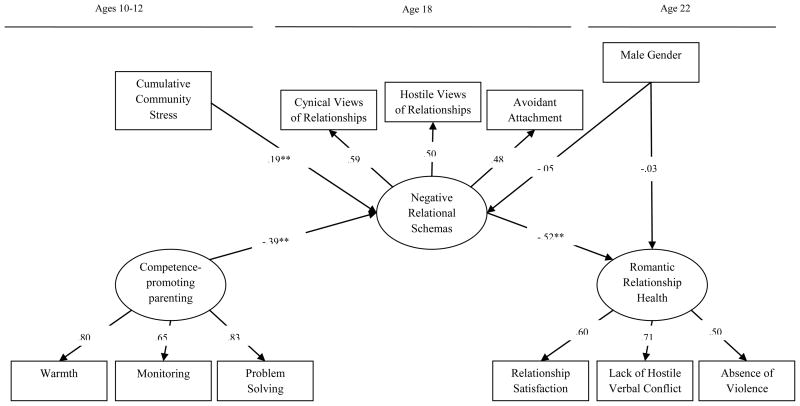

In this study, we investigated the ways in which parent and community processes in late childhood and negative relational schemas in adolescence affect African Americans’ romantic relationship health during young adulthood. Our hypotheses are summarized in Figure 1. We expected competence-promoting parenting, as indicated by youths’ report at ages 10 and 12 of parental monitoring, parental warmth, and parent-youth problem solving interactions, to predict negatively African American young adults’ negative relational schemas. We predicted that exposure during late childhood and early adolescence to community-related stressors, including community crime and deviance, victimization, and racial discrimination, would predict independently youths’ reports at age 18 of negative relational schemas. We expected youths’ reports of negative relational schemas, defined as hostile or cynical views of relationships and avoidant attachment styles, to predict romantic relationship health at age 22. We also expected family and community environments at ages 10 and 12 to affect indirectly romantic relationships in young adulthood via their influence on relational schemas. In our analyses, romantic relationship health was defined as a composite of young adult-reported satisfaction with the relationship, an absence of hostile angry conflict, and an absence of physical violence. Hypotheses were tested with a sample of 318 African American young people participating in a multiwave longitudinal study who reported having a steady dating partner.

Figure 1.

Study Hypotheses

Method

Sample

Hypotheses were tested with data from the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS), a multisite investigation of neighborhood and family effects on African Americans’ health and development (Simons, Lin, Gordon, Brody, & Conger, 2002). Census data were used to identify block group areas in Iowa and Georgia in which the percentages of African American families were 10% or higher. Families with a child 10 to 12 years of age were selected randomly from rosters and contacted via postal mail, with a follow-up telephone call to determine their interest in participating in the project. The response rate for the contacted families was 72%. Baseline data were collected on 889 families in Georgia (n = 467) and Iowa (n = 422).

Youths’ average age at baseline was 10.4 years (SD = .53); 54% were female. Of the primary caregivers, 84% were the youths’ biological mothers, 6% were fathers, 6% were grandmothers, and 4% were others; 92% of all primary caregivers identified themselves as African American, 6% as Caucasian, and 2% as other. Single-parent-headed households comprised approximately 52% of the sample. At baseline, primary caregivers’ mean age was 37.1 years (range = 23–80 years). Self-reported education levels and employment status indicated that 18% of the primary caregivers had less than a 12th grade education, 39% had a high school diploma or GED, 33% completed some college, 10% had a bachelor’s or graduate degree, 66% were employed full or part time, 3% were self-employed, 15% were unemployed, 4% were disabled, 2% were retired, 5% were students, and 5% were full-time homemakers. Median family income was $26,227, and mean number of children in the family was 3.42. Baseline data were collected in 1997–1998. Data from the two sites were merged due to considerable consistency in family demographic characteristics (Murry, Brown, Brody, Cutrona, & Simons 2001).

Hypotheses were tested with FACHS data from four time points. Target youths’ ages were 10.4 (SD = .53) years at Time 1, 12.2 (SD = .89) at Time 2, 18.2 (SD = .95) at Time 3, and 21.6 (SD = .83) at Time 4. At Time 4, 81% of the initial sample remained in the study. Demographic variables (e.g., target gender, caregiver education, and family income) did not differ by attrition status at Time 4. Of the 689 participants in the study at Time 4, 318 (46.2%) reported being in a committed romantic relationship (dating, cohabitating, or married); 189 of those in a committed relationship (59.4%) were female.

Procedures

To enhance rapport and cultural understanding, African American university students and community members served as field interviewers to collect data in the families’ homes. Project coordinators with a master’s degree in a behavioral science field were responsible for training and supervising the field interviewers. Project coordinators and investigators developed a manual and a training program for field interviewers, to ensure consistent and competent delivery of the measures at home visits. Before collecting data, the interviewers received approximately 20 hours of training in the administration of self-report instruments.

Primary caregivers consented to their own and their minor youths’ participation, and minor youth assented to their own participation. Upon reaching 18 years of age, youth consented to their own participation. At each home visit, interviews with youth and with caregivers were conducted privately. Person-to-person interviews were conducted at Times 1 through 3; at Time 4, audio computer-assisted self-interviews were conducted on laptop computers. Interviews took approximately 2 hours. Youth received $70.00 for their participation at Times 1 and 2, $100.00 at Time 3, and $140.00 at Time 4. Caregivers received $100.00 for each completed interview. All protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Georgia and Iowa State University.

Measures

Competence-Promoting Parenting

At Times 1 and 2, youth reported parent-youth relationship warmth, parental monitoring, and inductive parenting. The scales, described below, were developed for the Iowa Youth and Families Project (IYFP; Conger & Elder 1994); these measures have been shown to be valid and reliable with African American families, correlating with observer ratings (Simons 1996). In the case of each measure, associations of Time 1 and Time 2 indicators of parent-youth relationship warmth, parental monitoring, and inductive parenting covaried (r > .4; p < .001) and were summed across times for each measure. The composite scores were used as indicators of a latent construct encompassing competence-promoting parenting behavior that youth experienced from age 10 to 12.

Relationship warmth

Relationship warmth was assessed using nine items on which youth indicated, on a rating scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always), the extent to which their caregivers demonstrated sensitive and supportive behaviors during the past 12 months. A sample item is, “How often did your caregivers act supportive and understanding toward you?” Cronbach’s alphas were .82 at Time 1 and .88 at Time 2.

Parental monitoring

Parental monitoring practices were assessed using five items; for example, “During the past 12 months, how often did your caregiver know where you were and what you were doing?” Youth responded on a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). Cronbach’s alphas were .62 at Time 1 and .70 at Time 2.

Inductive reasoning

Caregiver use of inductive reasoning was assessed using five items concerning explanation of rules and expectations. A sample item is, “When you don’t understand why your [primary caregiver] makes a rule for you to follow, how often does your primary caregiver explain the reason?” The response set ranged from 1 (never) to 4 (always). Cronbach’s alphas were .75 at Time 1 and .80 at Time 2.

Cumulative Community Stress

Community stress was measured at Times 1 and 2 using youth reports of overt discrimination, subtle interpersonal racism, community deviance, and experiences with victimization. Cumulative community stress was calculated by summing the number of community stress indicators across Times 1 and 2 on which each youth scored above the median; possible scores ranged from 0 to 8.

Overt discrimination

Youths’ perceptions of overt discrimination were assessed with four items from the Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff 1996), using a rating scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (several times). A sample item is, “How often has someone yelled a racial slur or racial insult at you just because you are African American?” Cronbach’s alpha was .75.

Subtle, interpersonal discrimination

Subtle interpersonal racism were measured using five items from the Schedule of Racist Events (Landrine & Klonoff 1996) to assess the frequency with which youth experienced various interpersonal discriminatory events during the preceding year. The response set ranged from 1 (never) to 4 (several times). An example item is, “How often have you encountered whites who didn’t expect you to do well just because you are African American?” Cronbach’s alpha was .80.

Community crime

Community crime was assessed using a six-item measure (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls 1997) on which youth reported the frequency with which various criminal acts, such as fighting with weapons, robbery, gang violence, and sexual assault, occurred in their communities during the previous 6 months. The response scale ranged from 1 (never) to 4 (several times). A sample item is, “During the past 6 months, how often was there a robbery or mugging in your neighborhood?” Cronbach’s alpha was .72.

Victimization

Victimization was assessed with a single item: “While you have lived in this neighborhood, has anyone ever used violence, such as in a mugging, fight, or sexual assault, against you or any member of your household anywhere in your neighborhood?” Responses were dichotomous, 1 (yes) or 0 (no).

Negative relational schemas

We developed a latent relational schema construct indexed by youth reports on three measures at Time 3.

Hostile views of relationships

Hostile views of relationships were measured using a 10-item scale (Stewart & Simons 2010) based on Anderson’s (1997) theory of neighborhood street culture’s influences on youths’ delinquent behavior. A sample item is, “People tend to respect a person who is tough and aggressive.” The response scale ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha was .76.

Cynical views of relationships

Cynical views of relationships were measured using a four-item scale, developed for FACHS, to assess the degree of suspicion that youth held toward people and relationships. An example item is, “When people are friendly, they usually want something from you.” Items were rated dichotomously, 1 (true) and 2 (false). Cronbach’s alpha was .68.

Avoidant attachment

Avoidant attachment, defined as a dismissing and fearful orientation toward relationships, was assessed with four items from the Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised measure (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver 1998; Fraley & Shaver 2000). Example items include, “I don’t like people getting too close to me” and “I find it difficult to trust others completely.” Responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha was .81.

Romantic Relationship Health

A latent relationship health construct was developed from three indicators.

Relationship satisfaction

Relationship satisfaction was measured with two items from the Romantic Partner Relationship Satisfaction Scale (Huston, McHale, & Crouter, 1986): “How happy are you, all things considered, with your relationship?” with a response set of 1 (extremely unhappy) to 6 (extremely happy); and “How well do you and your romantic partner get along compared to most couples?” with a response set of 1 (a lot worse) to 5 (a lot better). These items were significantly correlated (r = .39, p <.001) and subsequently standardized and summed.

Lack of verbal abuse

Lack of verbal abuse was assessed by a four-item measure of the respondents’ reports of their verbal abuse (e.g., shout or yell and insult or swear) toward their partners and their partners’ verbal abuse toward them during the previous month (Donnellan, Assad, Robins, & Conger, 2007). The response format for these items ranged from 1 (always) to 4 (never). Cronbach’s alpha was .82. We coded this item dichotomously such that a “1” indicated lack that participants recorded a “4” (never) for all four items. Otherwise the score was coded a “0.”

Absence of violence

Absence of violence was measured by respondents’ reports of the occurrence of physical violence in the past month on items that addressed slapping or hitting, throwing things, or striking with an object). Three items addressed these behaviors implemented by the participant and three items addressed these behaviors implemented by the partner. An example item is “During the past month, how often did your Romantic Partner slap or hit you with (his/her) hands? Participants responded on a scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always). Absence of violence was coded dichotomously; “1” indicated that all six items were scored as never; otherwise the variable was coded as “0.”

Plan of Analysis

Preliminary analyses were conducted to determine if the subsample of individuals who identified themselves as being in a committed relationship differed from those who did not on key study variables. Study hypotheses were tested with structural equation modeling using Mplus software (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). Models were tested using full information maximum likelihood procedures, which test the model against all available data. Thus, data missing due to attrition do not produce missing cases; the interview protocols rendered nonresponse to individual items negligible. The measurement model was examined with a confirmatory factor analysis prior to hypothesis testing. The model presented in Figure 1 was then tested, with gender controlled and the significance of indirect pathways tested with bootstrapping. We then used multigroup modeling procedures to determine whether gender moderated the influence of competence-promoting parenting or community-related stressors on negative relational schemas. Model fit was assessed using chi-square, χ2/df < 2.0, comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

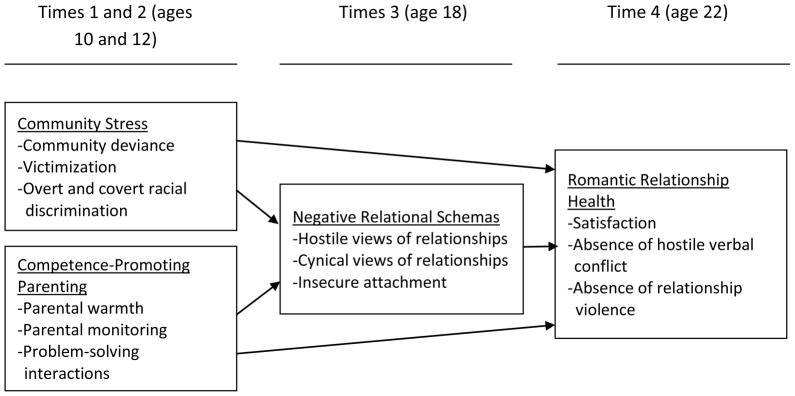

We first investigated mean differences between FACHS participants who at Time 4 reported a committed relationship and those who did not on gender and on indicators of competence-promoting parenting, exposure to community-related stress, and negative relationship schemas. No significant differences emerged. We then conducted a confirmatory factor analysis of the measurement model: χ2 (40) = 88.62, p = .00; χ2/df = 2.22; CFI = .91; RMSEA = .06 (.04, .08). All factor loadings were significant and in the expected direction, λ > .4. Associations among study variables, with means and standard deviations, are presented in Table 1. Indicators and their loadings on their respective constructs are presented as part of the final model in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Pearson Correlation Matrix Among Competence Promoting Parenting, Relational Schemas, and Romantic Relationship Health Indicators

| Indicator Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Cumulative community stress | — | ||||||||||

| 2. Warmth | −.118* | — | |||||||||

| 3. Monitoring | −.136* | .513** | — | ||||||||

| 4. Inductive reasoning | −.094 | .586** | .465** | — | |||||||

| 5. Cynical views of relationships | .170** | −.175** | −.189** | −.124* | — | ||||||

| 6. Hostile views of relationships | .141* | −.097 | −.210** | −.033 | .293** | — | |||||

| 7. Avoidant attachment | .052 | −.198** | −.186** | −.231** | .315** | .223** | — | ||||

| 8. Relationship satisfaction | −.025 | .190** | .152* | .137* | −.214** | −.181** | −.168** | — | |||

| 9. Lack of verbal abuse | −.148* | .079 | .104† | −.065 | −.201** | −.213** | −.101† | .415** | — | ||

| 10. Absence of violence | −.029 | .200** | .192** | .062 | −.154** | −.102† | −.009 | .273** | .393** | — | |

| 11. Gender | .045 | −.080 | .150* | −.012 | .066 | −.189** | −.014 | −.031 | −.037 | .096 | — |

|

| |||||||||||

| M | 3.000 | −.025 | −.017 | .006 | 1.768 | 25.233 | 14.011 | 8.281 | 13.573 | .7871 | .590 |

| SD | 2.081 | 1.737 | 1.682 | 1.648 | 1.354 | 4.345 | 5.425 | 1.813 | 2.177 | .411 | .493 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Figure 2.

Structural Equation Model of Pathways to African American Young Adults’ Relationship Health

χ2 = 81.93, df = 38, p = .00. RMSEA = .05 and CFI = .92. **p ≤.01; *p ≤.05, †p < .10 (two-tailed tests), N = 318.

Test of the Conceptual Model

The test of the conceptual model with standardized parameter coefficients is presented in Figure 2. The model fit the data well: χ2(44) = 101.73, p < .001; x2/df = 2.3; CFI = .94; RMSEA = .0439 (.027, .067). χ2 = 101.728, df = 44, p = .000. RMSEA = .039 and CFI=.94. As hypothesized, cumulative community stress and competence-promoting parenting in late childhood were significant predictors of relational schemas at age 19. In turn, relational schemas constituted a robust (β = .50) and significant (p < .01) predictor of romantic relationship health at age 22. Mediational pathways were tested with bootstrapping; the results of the indirect effect analysis are presented in Table 2. Consistent with our hypotheses, the exogenous variables (community stress or competence-promoting parenting) had a significant indirect effect on romantic relationship health via their influence on negative relational schemas. Participant gender, which was included in the model as a control variable, was not a significant predictor of either relational schemas or romantic relationship health.

Table 2.

Indirect Effects

| Predictors | Mediator | Outcome | Indirect Effect [95% CI] | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community stress | Negative Relational Schemas | Relationship Health | −.050 [−.099, −.001] | .045 |

| Competence-promoting parenting | .125 [.021, .229] | .018 |

The role of gender as a moderator of the associations among competence-promoting parenting, community-related stressors, negative relational schemas, and romantic relationship health was investigated. We first estimated a multigroup model in which the parameters for each path were constrained to equality. A second analysis allowed each parameter to vary by gender. A significant difference in model chi-square suggests moderation. No significant differences emerged, suggesting that the effects in the model operated similarly for men and women.

Discussion

Accumulating evidence indicates that young African American adults experience significant challenges in developing and maintaining stable, satisfying romantic relationships (Burton & Tucker 2009; Dixon 2009; Fields 2004). To date, research on the factors associated with African Americans’ romantic relationship quality has focused primarily on contemporaneous contextual factors that are negatively associated with relationship health (Chapman, 2007; Conger et al., 2002; Cutrona, Russell, Burzette, Wesner, & Bryant, 2011). Although important, this research does not include consideration of childhood and adolescent experiences that could be pivotal in determining how individuals will experience later romantic relationships. Informed by ecological (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998) and attachment (Steinberg, Davila, & Fincham 2006) perspectives on the development of romantic relationship behavior we investigated the pathways from contextual influences in late childhood and relationship schemas in adolescence on young adult romantic relationship health among African Americans. We hypothesized that competence-promoting parenting and community-related stressors at ages 10 and 12 would predict African American youths’ negative relational schemas at age 18. We expected youths’ reports of negative relational schemas, to predict romantic relationship health at age 22. Hypotheses were tested with a sample of 318 African American young people participating in a multiwave longitudinal study who reported having a steady dating partner.

Study results were consistent with our predictions. Competence-promoting parenting and community stressors in late childhood forecast relational schemas in late adolescence, which in turn predicted reported relationship health. Indirect effect analyses supported the role of relational schemas in mediating the influence of parenting and community contextual processes at an earlier stage of development on subsequent relationship health.

Findings from this study are consistent with attachment perspectives on the development of adult romantic relationships (Conger et al., 2000). According to these perspectives, caregiving practices experienced during childhood and adolescence affect relationships in adulthood. We hypothesized that warm, regulated caregiver behavior characterized by nurturing, monitoring, and inductive parenting practices affect youths’ working models of relationships in general, which shape their interpretations of experiences within adult romantic relationships (Steinberg, Davila, & Fincham 2006). From an attachment perspective, this core relationship experience suggests that relationships can be nurturing and predictable, with the potential for negotiation. Consistent with past research primarily with Caucasian youth (Conger et al., 2000; Furman & Escudero, 2006), parenting practices were a robust predictor of relationship schemas. Those youth who experienced competence-promoting parenting were less likely to report relationship schemas characterized by hostility, cynicism, and avoidance. Bolstering the proposition that, among African Americans, parenting influences future romantic relationship health via internalized schemas, the relational schema construct was a significant mediator of the link between competence-promoting parenting and young adult relationship health.

Study results indicate that community-based contextual variables also influence relational schemas. Though families are the most proximal influence on youth development, an ecological perspective (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998) emphasizes the ways in which communities affect development. This is particularly true during adolescence, when youth become more independent and spend more time away from home and from adult supervision. African American youth are disproportionally exposed to community-related stressors that have the potential to disrupt healthy development and affect romantic relationship health (Burton & Tucker 2009). Exposure to deviance in communities and racial discrimination can lead individuals to expect poor treatment from others in interpersonal relationships (Guyll, Cutrona, Burzette, & Russell 2010) and contribute to a negative view of relationships. Such experiences can lead individuals to become defensive, guarded, and overly focused on self-reliance, rendering formation of healthy relationships with romantic partners difficult. African Americans’ disproportionate exposure to discrimination, community poverty, and deviance may form the basis of racial disparities in the establishment and maintenance of long-term romantic unions (Dixon 2009). Among the African American young people in the study, exposure to community-related stressors in late childhood predicted negative relational schemas independently of parenting.

The results of this study have implications for research, practice, and policy. To address disparities in marital and dating relationship quality, clinicians, interventionists, and policy makers must consider the characteristics of African Americans’ preadolescent and adolescent environments that shape relationship behavior. Intervention that takes place while young people are developing relational schemas may have enduring effects on later relationship quality or marital quality. Such intervention should target the enhancement of competence-promoting parenting practices and the reduction of youths’ exposure to community-related stressors. For example, the Strong African American Families (SAAF) program is an evidence-based family skills intervention suitable for both single-parent and two-parent homes. The program targets competence-promoting parenting and is effective in reducing youth substance use and conduct problems (Brody, Kogan, & Grange, 2012; Brody, Murry, et al., 2004). Although the intervention did not focus on romantic relationships, the present findings suggest that the parenting behaviors targeted in SAAF and similar programs also may influence young people’s involvement in healthy relationships as young adults. Moreover, the enhancement of practices such as parental monitoring may be valuable in limiting the influence that community stressors exert on youth development. For example, Brody and associates (Brody, Chen, et al., 2006) found that competence-promoting parenting attenuated the influence of racial discrimination on youths’ psychological adjustment. Individuals’ relationship schemas also may constitute an important mechanism of change for behavioral interventions. Studies indicate that relational schemas are malleable and can respond to intervention (Toth, Maughan, Manly, Spagnola, & Cicchetti, 2002).

Limitations of this study should be noted. The analyses were based on single-informant reports; thus, they may be subject to method bias. Most of the caregivers in the sample were mothers. Consequently, we cannot generalize the findings to the role that fathers may have in the development of relational schemas and relationship health. Future research may benefit from considering the influences of mothers and fathers separately.

These limitations notwithstanding, the current research adds to the understanding of issues affecting relationship experiences among African American young adults. Prior research is limited in its focus on contemporaneous correlates of relationship health and prospective studies in this area have not focused on African American young people. The present research identifies key contextual contributors experienced in late childhood that contribute to relationship health. These contextual factors provide intervention targets for prevention efforts underscoring the importance of enhancing parenting and reducing youths’ exposure to community stressors. This study also identified a key cognitive mediator of contextual effects through which late childhood experiences carry forward to affect later romantic relationships. Consideration of relationship schemas allows interventionists to identify and respond to adolescents who may experience relationship problems in the future and offers a malleable, cognitive process that can be targeted in interventions to improved relationship health.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Award R01MH062669 from the National Institute of Mental Health, Award R01DA21898 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and Award R01HD030588 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, or the National Institutes of Health. Yi-fu Chen is now at the Department of Sociology, National Taipei University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Biographies

Steven M. Kogan is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Science at the University of Georgia. He received his PhD in Child and Family Development from the University of Georgia. His research interests include the development of romantic and sexual behavior among African American youth and the development of prevention programs to deter youth risk behavior.

Christina R. Grange is a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Georgia. She received her PhD in Clinical Psychology from Virginia Commonwealth University. Her major research interests include contextual factors that facilitate adaptive co-parenting among African American emerging adults, and factors associated with their development of healthy intimate relationships prior to becoming parents.

Man-Kit Lei is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Sociology at the University of Georgia and a Statistician at the Center for Family Research. His interests focus on the influence of community environments on adult health.

Ronald L. Simons is a Distinguished Research Professor of Sociology at the University of Georgia. He received his PhD in Sociology from Florida State University. His major research interests include risks that contribute to delinquency and emotional problems among adolescents, the causes and consequences of domestic violence, and racial socialization as a moderator of the consequences of discrimination.

Gene H. Brody is a Regents’ Professor Emeritus and the Director of the Center for Family Research at the University of Georgia. He received his PhD in Developmental Psychology from the University of Arizona. His major research interests include family, community, and genetic contributions to child and adolescent development; resilience processes; and the development, evaluation, and dissemination of family-centered preventive interventions.

Frederick X. Gibbons is a Research Professor in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Dartmouth College. He received his PhD from the University of Texas. His major research interests include health and clinical applications of social psychology theory and principles, the association of racial discrimination with health behaviors, and the application of the Prototype/Willingness model to the study of risk behaviors.

Yi-fu Chen is now at the Department of Sociology at the National Taipei University in Taiwan. He received his PhD in Sociology at Iowa State University with a minor in statistics. His major research interests include mental health, parenting, and peer relationships as they apply to the development of adolescent delinquency. He is also interested in the development of methodology that can be applied to the study of these topics.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

SK conceived of the study, led design and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. ML and YC conducted data analyses CG participated in the design of the study, data analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. RS, GH, and FG participated in data acquisition and made substantive contributions to the manuscript regarding interpretation of findings and significance of the research.

References

- Ackerman BP, Brown ED, Izard CE. The relations between contextual risk, earned income, and the school adjustment of children from economically disadvantaged families. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:204–216. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Violence in the inner city. In: McCord J, editor. Violence and childhood in the inner city. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson E. Code of the street: Decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. New York, NY: Norton; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin MW. Relational schemas and the processing of social information. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;112:461–484. [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Smith DA, Fincham FD. Marital interventions for depression: Empirical foundation and future prospects. Applied & Preventive Psychology. 1994;3:233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Black KA, Schutte ED. Recollections of being loved: Implications of childhood experiences with parents for young adults’ romantic relationships. Journal of Family Issues. 2006;27:1459–1480. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd-Franklin N. Black families in therapy: Understanding the African American experience. 2. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan KA, Clark CL, Shaver PR. Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Chen Y-f, Murry VM, Ge X, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, et al. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development. 2006;77:1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Kim S, Murry VM, Brown AC. Protective longitudinal paths linking child competence to behavioral problems among African American siblings. Child Development. 2004;75:455–467. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00686.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Kogan SM, Grange CM. Translating longitudinal, developmental research with rural African American families into prevention programs for rural African American youth. In: Maholmes V, King RB, editors. The Oxford handbook of poverty and child development. New York, NY: Oxford University Press-USA; 2012. pp. 553–570. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Murry VM, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Molgaard V, McNair LD, et al. The Strong African American Families program: Translating research into prevention programming. Child Development. 2004;75:900–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Dorsey S, Forehand R, Armistead L. Unique and protective contributions of parenting and classroom processes to the adjustment of African American children living in single-parent families. Child Development. 2002;73:274–286. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Kogan SM, Chen Y-f. Perceived discrimination and longitudinal increases in adolescent substance use: Gender differences in mediational pathways. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:1006–1011. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The ecology of developmental processes. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Volume 1: Theoretical models of human development. 5. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 1998. pp. 993–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant CM, Taylor RJ, Lincoln KD, Chatters LM, Jackson JS. Marital satisfaction among African Americans and Black Caribbeans: Findings from the National Survey of American Life. Family Relations. 2008;57:239–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant CM, Wickrama KAS, Bolland J, Bryant BM, Cutrona CE, Stanik CE. Race matters, even in marriage: Identifying factors linked to marital outcomes for African Americans. Journal of Family Theory and Review. 2010;2:157–174. [Google Scholar]

- Burton LM, Tucker MB. Romantic unions in an era of uncertainty: A post-Moynihan perspective on African American women and marriage. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2009;621:132–148. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman AB. In search of love and commitment. In: McAdoo HP, editor. Black families. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. pp. 258–296. [Google Scholar]

- Ciarocco NJ, Echevarria J, Lewandowski GW., Jr Hungry for love: The influence of self-regulation on infidelity. Journal of Social Psychology. 2012;152:61–74. doi: 10.1080/00224545.2011.555435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Welsh DP, Furman W. Adolescent romantic relationships. Annual Review of Psychology. 2009;60:631–652. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Cui M, Bryant CM, Elder GH., Jr Competence in early adult romantic relationships: A developmental perspective on family influences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:224–237. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Elder GH. Families in troubled times: Adapting to change in rural America. New York, NY: Aldine de Gruyter; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Wallace LE, Sun Y, Simons RL, McLoyd VC, Brody GH. Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:179–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick NR, Dodge KA. A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:74–101. [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Burzette RG, Wesner KA, Bryant CM. Predicting relationship stability among midlife African American couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:814–825. doi: 10.1037/a0025874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Abraham WT, Gardner KA, Melby JM, Bryant C, et al. Neighborhood context and financial strain as predictors of marital interaction and marital quality in African American couples. Personal Relationships. 2003;10:389–409. doi: 10.1111/1475-6811.00056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deitch EA, Barsky A, Butz RM, Chan S, Brief AP, Bradley JC. Subtle yet significant: The existence and impact of everyday racial discrimination in the workplace. Human Relations. 2003;56:1299–1324. [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Current Population Reports, P60–236. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2009. Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dinero RE, Conger RD, Shaver PR, Widaman KF, Larsen-Rife D. Influence of family of origin and adult romantic partners on romantic attachment security. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:622–632. doi: 10.1037/a0012506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon P. Marriage among African Americans: What does the research reveal? Journal of African American Studies. 2009;13:29–46. [Google Scholar]

- Felix Ortiz M, Newcomb MD. Vulnerability for drug use among Latino adolescents. Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:257–280. [Google Scholar]

- Fields J. Current Population Reports, P20–553. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2004. America’s families and living arrangements: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Florsheim P, Moore DR. Observing differences between healthy and unhealthy adolescent romantic relationships: Substance abuse and interpersonal process. Journal of Adolescence. 2008;31:795–814. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Shaver PR. Adult romantic attachment: Theoretical developments, emerging controversies, and unanswered questions. Review of General Psychology. 2000;4:132–154. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Escudero H. The role of developmental context in romantic relationships. Paper presented at the Society for Research on Adolescence; San Francisco, CA. 2006. Mar, [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Simon VA, Shaffer L, Bouchey HA. Adolescents’ working models and styles for relationships with parents, friends, and romantic partners. Child Development. 2002;73:241–255. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:218–238. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman LM, Sameroff AJ, Eccles JS. The academic achievement of African American students during early adolescence: An examination of multiple risk, promotive, and protective factors. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30:367–400. doi: 10.1023/A:1015389103911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyll M, Cutrona C, Burzette R, Russell D. Hostility, relationship quality, and health among African American couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:646–654. doi: 10.1037/a0020436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huston T, McHale S, Crouter A. When the honeymoon’s over: Changes in the marriage relationship over the first year. In: Gilmour R, Duck S, editors. The emerging field of personal relationships. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1986. pp. 109–132. [Google Scholar]

- Jones JM. Exposure to chronic community violence: Resilience in African American children. Journal of Black Psychology. 2007;33:125–149. [Google Scholar]

- Karney BR, Beckett MK, Collins RL, Shaw R. Adolescent romantic relationships as precursors of healthy adult marriages: A review of theory, research, and programs. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly BM, Schwartz D, Gorman AH, Nakamoto J. Violent victimization in the community and children’s subsequent peer rejection: The mediating role of emotion dysregulation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:175–185. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Brody GH, Chen Y-f, Grange CM, Slater LM, DiClemente RJ. Risk and protective factors for unprotected intercourse among rural African American emerging adults. Public Health Reports. 2010;25:709–717. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Yu T, Brody GH, Allen KR. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2012. Nov 14, The development of conventional sexual partner trajectories among African American male adolescents. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogan SM, Brody GH, Molgaard VK, Grange C, Oliver DAH, Anderson TN, et al. The Strong African American Families–Teen trial: Rationale, design, engagement processes, and family-specific effects. Prevention Science. 2012;13:206–217. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0257-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreider RM, Ellis R. Number, timing, and duration of marriages and divorces: 2009. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek LA. Differences between partners from Black and White heterosexual dating couples in a path model of relationship commitment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2008;25:51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Landor A, Simons LG, Simons RL, Brody GH, Gibbons FX. The role of religiosity in the relationship between parents, peers, and adolescent risky sexual behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2011;40:296–309. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9598-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA. The Schedule of Racist Events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:144–168. [Google Scholar]

- Lee R. Community violence exposure and adolescent substance use: Does monitoring and positive parenting moderate risk in urban communities? Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;40:406–421. [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln KD, Chae DH. Stress, marital satisfaction, and psychological distress among African Americans. Journal of Family Issues. 2010;31:1081–1105. [Google Scholar]

- McKelvey LM, Whiteside-Mansell L, Bradley RH, Casey PH, Conners-Burrow NA, Barrett KW. Growing up in violent communities: Do family conflict and gender moderate impacts on adolescents’ psychosocial development? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39:95–107. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9448-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNulty TL, Bellair PE. Explaining racial and ethnic differences in adolescent violence: Structural disadvantage, family well-being, and social capital. Justice Quarterly. 2003;20:1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Gorman-Smith D, Sullivan T, Orpinas P, Simon TR. Parent and peer predictors of physical dating violence perpetration in early adolescence: Tests of moderation and gender differences. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38:538–550. doi: 10.1080/15374410902976270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. Mplus Version 7: User’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Riina EM, McHale SM. Parents’ experiences of discrimination and family relationship qualities: The role of gender. Family Relations. 2010;59:283–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997 Aug 15;277:918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpa A, Haden SC. Community violence victimization and aggressive behavior: The moderating effects of coping and social support. Aggressive Behavior. 2006;32:502–515. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield TJ, Conger RD, Conger KJ, Martin MJ, Brody G, Simons R, et al. Neighborhood disorder and children’s antisocial behavior: The protective effect of family support among Mexican American and African American families. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;50:101–113. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9481-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sieger K, Rojas-Vilches A, McKinney C, Renk K. The effects and treatment of community violence in children and adolescents: What should be done? Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2004;5:243–259. doi: 10.1177/1524838004264342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons R. Understanding differences between divorced and intact families: Stress, interaction, and child outcome. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Lin KH, Gordon LC, Brody GH, Conger RD. Community differences in the association between parenting practices and child conduct problems. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:331–345. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Simons LG, Burt CH, Drummund H, Stewart E, Brody GH, et al. Supportive parenting moderates the effect of discrimination upon anger, hostile view of relationships, and violence among African American boys. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2006;47:373–389. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Simons LG, Lei MK, Landor A. Relational schemas, romantic relationships, and beliefs about marriage among young African American adults. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2012;29:77–101. doi: 10.1177/0265407511406897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg SJ, Davila J, Fincham F. Adolescent marital expectations and romantic experiences: Associations with perceptions about parental conflict and adolescent attachment security. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35:333–348. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart EA, Simons RL. Race, code of the street, and violent delinquency: A multilevel investigation of neighborhood street culture and individual conduct norms. Criminology. 2010;48:569–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2010.00196.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DE, Woodburn EM, Thompson CI, Leff SS. Contemporary interventions to prevent and reduce community violence among African American youth. In: Lemelle AJ, Reed W, Taylor S, editors. Handbook of African American health: Social and behavioral interventions. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. pp. 113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Maughan A, Manly JT, Spagnola M, Cicchetti D. The relative efficacy of two interventions in altering maltreated preschool children’s representational models: Implications for attachment theory. Development and Psychopathology. 2002;14:877–908. doi: 10.1017/s095457940200411x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickrama KAS, Bryant CM, Wickrama TKA. Perceived community disorder, hostile marital interactions, and self-reported health of African American couples: An interdyadic process. Personal Relationships. 2010;17:515–531. [Google Scholar]