SUMMARY

Interactions between phytohormones play important roles in the regulation of plant growth and development, but knowledge of the networks controlling hormonal relationships, such as between oxylipins and auxins, is just emerging. Here, we report the transcriptional regulation of two Arabidopsis YUCCA genes, YUC8 and YUC9, by oxylipins. Similarly to previously characterized YUCCA family members, we show that both YUC8 and YUC9 are involved in auxin biosynthesis, as demonstrated by the increased auxin contents and auxin-dependent phenotypes displayed by gain-of-function mutants as well as the significantly decreased IAA levels in yuc8 and yuc8/9 knockout lines. Gene expression data obtained by qPCR analysis and microscopic examination of promoter-reporter lines reveal an oxylipin-mediated regulation of YUC9 expression that is dependent on the COI1 signal transduction pathway. In support of these findings, the roots of the analyzed yuc knockout mutants displayed a reduced response to methyl jasmonate (MeJA). The similar response of the yuc8 and yuc9 mutants to MeJA in cotyledons and hypocotyls suggests functional overlap of YUC8 and YUC9 in aerial tissues, while their function in roots show some specificity, likely in part related to different spatio-temporal expression patterns of the two genes. These results provide evidence for an intimate functional relationship between oxylipin signaling and auxin homeostasis.

Keywords: YUCCA genes, auxin, jasmonic acid, hormone signaling, plant hormone interaction, root development, Arabidopsis

INTRODUCTION

Oxylipins, such as jasmonates and their precursor 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid (OPDA), are pleiotropic plant growth regulators that are widely represented throughout the plant kingdom (Böttcher and Pollmann, 2009). These bioactive signaling molecules regulate various plant developmental processes including anther dehiscence, pollen maturation, and root growth. In addition, they are well-known mediators of abiotic and biotic stress responses, e.g. to pathogen attack and herbivory (Howe and Jander, 2008; Wasternack, 2007).

There is mounting evidence of extensive interaction between phytohormones in the regulation on plant growth and development or their adaptation to external stimuli (Wolters and Jürgens, 2009). These interactions are in some cases governed by shared components of signal transduction pathways, but in other cases reflect the modulation that a given hormone exerts on the synthesis or action of another one (Hoffmann et al., 2011). Jasmonates make no exception and numerous interactions of jasmonates with other hormones have been reported (Kazan and Manners, 2008). Among those, the interaction between jasmonic acid (JA) and auxin is still poorly understood despite growing evidence for significant interactions between these two seemingly antagonistic signaling molecules, in particular in regulating adventitious root initiation (Gutierrez et al., 2012), and coleoptile photo- and gravitropism (Gutjahr et al., 2005; Riemann et al., 2003). In addition, there seems to be an intimate interplay between JA and IAA in the control of lateral root formation (Sun et al., 2009).

Besides shared components in ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation pathways such as AXR1 and AXR6 (Ren et al., 2005; Tiryaki and Staswick, 2002), and shared co-repressors like TPL (Pauwels et al., 2010; Szemenyei et al., 2008), auxin and JA pathways are linked through the action of auxin response factors (ARFs) which regulate the transcription of auxin-dependent genes. In addition to an impaired auxin response, arf6/arf8 mutants exhibit aberrant flower development, and JA deficiency as well as reduced transcription of JA biosynthetic genes in their flowers (Nagpal et al., 2005). The essential role of JA in the regulation of flower development has been previously documented (Ishiguro et al., 2001). Moreover, auxin is capable of inducing the expression of JA biosynthetic genes (Tiryaki and Staswick, 2002), while JA increases the metabolic flux into the L-tryptophan (Trp) pathway by inducing gene expression of ANTHRANILATE SYNTHASE α1 (ASA1) and β1 (ASB1). Elevated ASA1 and ASB1 expression leads to increased production of Trp, a precursor for the synthesis of active auxin, namely indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), and indole glucosinolate (Dombrecht et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2009). Recently, jasmonates have also been reported to be involved in the regulation of auxin transport through effects on the distribution of the auxin exporter PIN-FORMED 2 (PIN2) (Sun et al., 2011).

Although the intricacies of IAA biosynthesis still need to be fully elucidated, both genetic and biochemical studies suggest that YUCCA enzymes play a role in the production of IAA (Dai et al., 2013; Mashiguchi et al., 2011; Stepanova et al., 2011; Won et al., 2011). In Arabidopsis, the YUCCA gene family consists of eleven members encoding flavin-containing monooxygenase-like proteins. Several YUCCA enzymes, i.e. YUC1-6 and YUC10-11, have been implicated in the local production of auxin (Cheng et al., 2006, 2007; Kim et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2007; Woodward et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2001) and the transcription of the YUCCA genes appears to be strictly spatio-temporally regulated (Zhao, 2008). Knowledge of the transcriptional networks by which the expression of the YUCCA genes is regulated, however, just emerges.

Recent studies attracted our attention by providing circumstantial evidence for the induction of two YUCCA genes, YUC8 and YUC9, by wounding. For example, induction of YUC9 expression was described in response to OPDA treatment both in the tga2/5/6 triple-mutant and the wild type background (Mueller et al., 2008). Another dataset from an Arabidopsis cell culture experiment gave evidence for a 4-fold rapid and transient increase of YUC8 gene expression in response to MeJA application (Pauwels et al., 2008). These results prompted us to hypothesize that YUC8 and YUC9 may play an important role in linking oxylipin signaling and IAA metabolism.

Here, we analyze these two as yet uncharacterized members of the Arabidopsis YUCCA gene family. We demonstrate a role of the two genes in auxin homeostasis and root development as well as in hypocotyl and leaf phenotypes typically associated with changes in IAA levels. We show that both genes participate in the induction of auxin synthesis by MeJA and other oxylipins. Our data provide evidence for partial redundancy between the two genes, but also reveal specific functions with respect to their spatio-temporal expression patterns as well as their involvement in the interplay of auxin and oxylipins.

RESULTS

YUC8 and YUC9 contribute to auxin production in vivo

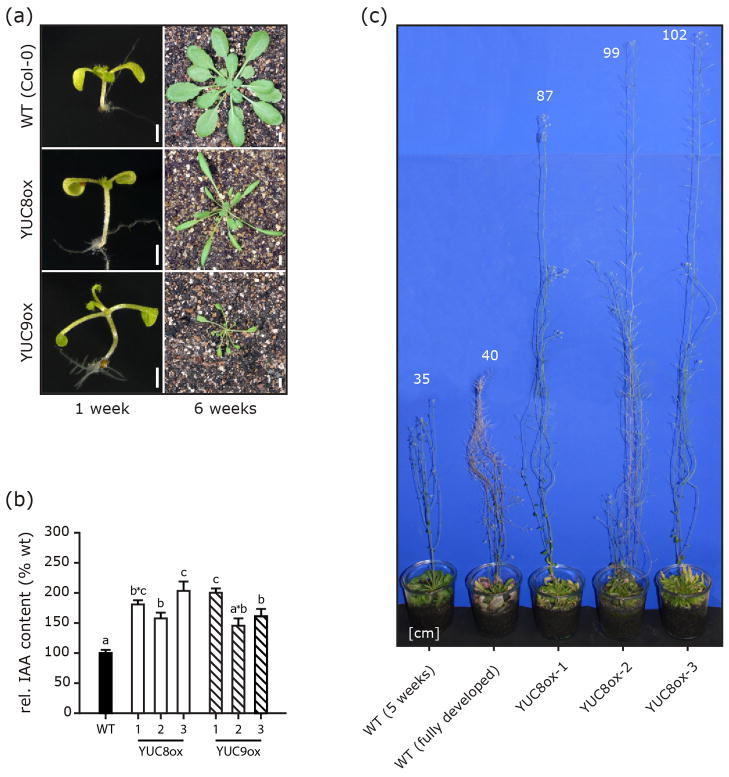

As a first step to investigate YUC8 and YUC9 function, we generated stable 35S::YUC8 and 35S::YUC9 overexpression lines (YUC8ox, YUC9ox). Several independent homozygous YUC8ox and YUC9ox lines were recovered. All displayed a phenotype similar to other auxin overproducers, e.g. yucca, CYP79B2ox, or rooty (Zhao et al., 2002), with elongated hypocotyls, epinastic cotyledons, reduced primary root lengths, and narrow elongated leaf blades and petioles (Figure 1a). Hypocotyl length in YUC8ox and YUC9ox was 1.6- and 2-fold greater, respectively, than in wild type, similar to hypocotyl elongation earlier observed in sur1/rooty or sur2 mutants, showing a 2- to 3-fold increase (Boerjan et al., 1995; King et al., 1995). It is noteworthy, however, that free IAA levels in both YUC8ox and YUC9ox (Figure 1b), as well as in other previously characterized YUCCA overexpressing lines (Zhao et al., 2001) are only 1.5- to 2-fold higher than those in wild type. This contrasts with the 5- to 20-fold increase of IAA contents in sur1/rooty and sur2 (King et al., 1995; Sugawara et al., 2009). This may emphasize the importance of the spatio-temporal distribution of IAA-overproduction, constitutive and unspecific in the YUCox lines due to the use of a 35S promoter to drive overexpression, but most probably tissue/cell specific in the superroot knockout mutants.

Figure 1.

Phenotype of YUC8 and YUC9 overexpression lines. One-week-old and six-week-old plants of wt as well as YUC8ox and YUC9ox lines are shown (a). [Scale bars, 1 mm on the left, 5 mm on the right]. (b) Elevated levels of IAA in YUC8- and YUC9-overexpressing lines. IAA levels were determined by GC-MS analysis. For each construct, three independent lines were analyzed and compared to wt. IAA levels are normalized to 100% in wt. Means are given with their SE (n = 6). Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments. Different letters indicate significant differences between means [P < 0.05]. (c) Arabidopsis overexpressing YUC8 exhibit strongly enhanced shoot growth and stem elongation. Numbers in the figure indicate plant heights in cm. Similar results were obtained for 35S::YUC9 lines, showing maximum heights of 120 cm (data not shown).

Like 35S::YUC6 transgenic plants (Kim et al., 2011), adult YUC8ox and YUC9ox plants showed considerable longevity, with some lines reaching heights of more than one meter (Figure 1c). To test the hypothesis that elevated IAA levels were the cause of the aberrant phenotypes associated with YUC8/9 overexpression, auxin levels were measured in a number of independent transgenic lines by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. In agreement with previous reports on auxin contents in other YUCCA-overexpressing lines (Zhao et al., 2001), endogenous auxin levels in our lines were increased by 1.5- to 2-fold when compared to wild type levels (Figure 1b). Consistent with the assumption of a role of YUCCA genes in Trp-dependent auxin synthesis (Mashiguchi et al., 2011; Stepanova et al., 2011; Won et al., 2011; Zhao et al., 2001), the examined lines showed an increased resistance towards toxic 5-methyl-tryptophan (5-mT) (Figure S1). Even though 5-mT is ultimately lethal to wild type and YUCCA overexpressing plants by inhibiting Trp formation and blocking the function of proteins in which this amino acid is incorporated (Hull et al., 2000), it seems as if part of the 5-mT is shunted into non-toxic 5-methyl IAA thereby increasing the resistance of YUC8ox and YUC9ox.

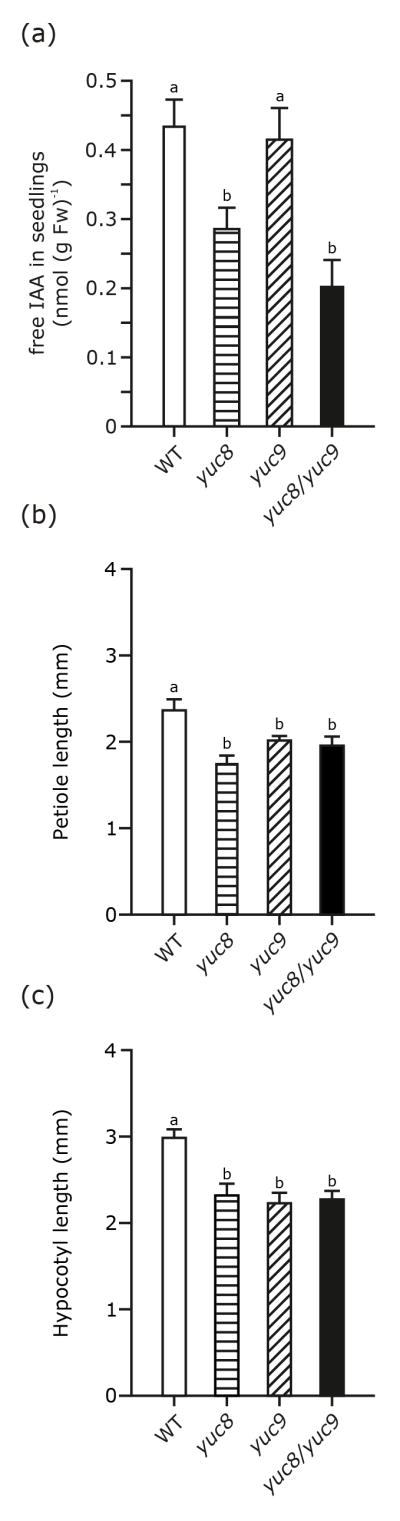

We also used the 35S::YUC8 and 35S::YUC9 overexpression vectors to perform transient assays on Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. Within 18 hrs post-infiltration, leaves infiltrated with either construct showed strong curling compared to control leaves infiltrated with Agrobacterium tumefaciens harboring an empty vector (Figure S2a–b). Inspection of leaf epidermis revealed that expression of both YUC8 and YUC9 caused a 2–2.5-fold increase in pavement cell size (Figure S2c-e). These observations are in agreement with previous studies on auxin overproducers showing similar leaf curling (Zhang et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2001). To confirm the results obtained in our YUC8 and YUC9 overexpression experiments, we analyzed IAA levels in seven-day-old yuc8 and yuc9 single- and yuc8/yuc9 double-knockout mutants. Relative to the wild type, two out of three mutants showed significantly reduced IAA contents (Figure 2a). The most severe reduction was detected in yuc8/yuc9 double-knockout seedlings with an IAA level approximately 50% of that in wt compared to 70% for the yuc8 single mutant. The impact of YUC9 loss-of-function on the endogenous IAA pool was not statistically significant with a decrease of only 5–10% compared to wild-type levels. All mutants showed slightly reduced hypocotyl (75%) and petiole (83%) lengths (Figure 2b–c), in line with observations in other mutants with low auxin contents such as the ilr1/iar3 double-and the ilr1/iar3/ill2 triple-knockout mutants or the sav3-2 mutant (Rampey et al., 2004; Tao et al., 2008). Taken together, these results indicate that YUC8 and YUC9 both contribute to auxin synthesis in Arabidopsis. In addition, the additive effects on the IAA levels detected in the mutant seedlings under normal conditions (Figure 2a) reveal that YUC8 and YUC9 seemingly act in parallel to maintain auxin homeostasis.

Figure 2.

Endogenous auxin contents and phenotype of yuc8 and yuc9 single- and double-knockout mutants. (a) IAA contents in seven-day-old seedlings. Auxin contents were quantified by GC-MS analysis. Means are given with their SE (n = 6). Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. Different letters indicate significant differences between means [P < 0.05]. Seedlings grown for seven days on vertical MS plates were analyzed for their (b) petiole and (c) hypocotyl length. Both petioles and hypocotyls are significantly shorter in the mutants. Given are means with their SE (n = 8–10 seedlings). Different letters indicate significant differences between means [P < 0.05].

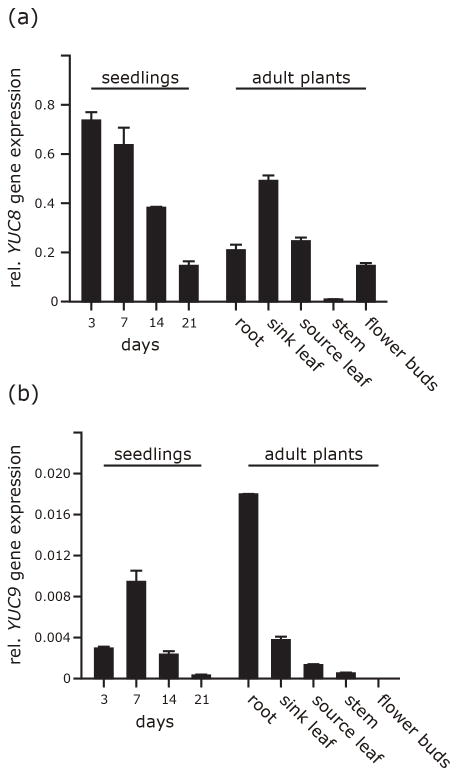

YUC8 and YUC9 have distinct expression patterns

To examine the degree of redundancy between the two genes, we analyzed tissue-specific expression levels by qRT-PCR (Figure 3). YUC8 expression was highest in very young 3 and 7d-old seedlings, thereafter declining. In adult 6–8 week-old plants, YUC8 transcript levels were highest in young sink leaves, lower in mature source leaves, roots, and flower buds, and hardly detectable in stems (Figure 3a). YUC9 gene expression was generally one order of magnitude lower than YUC8 expression (Figure 3b). It was also developmentally regulated in young seedlings but with a peak 7 days after germination. In adult plants, YUC9 was predominantly expressed in roots and at a much lower level in sink leaves, while being undetectable in floral tissue. These patterns are consistent with microarray data deposited in public databases, e.g. the Genevestigator database (Hruz et al., 2008), and indicate marked differences in the spatio-temporal expression patterns of the two genes.

Figure 3.

Tissue specific expression of YUC8 (a) and YUC9 (b) in wild type. Transcript abundance values are given relative to the geometric means of APT1 and UBQ10 transcripts. Error bars are given ± SE.

We next generated pYUC8::GUS and pYUC9::GUS reporter lines allowing for finer resolution in the examination of cellular and tissue specificity in YUC8 and YUC9 expression. Within two days of germination, expression of both YUC8 and YUC9 was detectable in primary root tips, and within the next two days became visible in the root vasculature (Figure S3). In older plants, GUS reporter activity was absent from leaves (YUC8) or confined to the very margin of sink leaves (YUC9, Figure S4h). The two genes were expressed in reproductive organs but with quite distinct patterns. YUC8 showed high specific expression in flower buds (Figure S4c). Closer examination of flowers revealed YUC8 promoter activity in the young anthers of immature flowers (Figure S4i) and in the vascular tissues of sepals and petals of mature flowers as well as in anther filaments (Figure S4i–m) and the funiculus and integuments of young ovules (Figure S5b–d). These results extend the previously described pattern of YUC8 promoter activity (Rawat et al., 2009) and suggest a role for YUC8 in reproductive development. By contrast, there was no detectable YUC9 promoter activity in floral tissues, but transient expression in the suspensor of the embryo, at the 8- and 16-cell stage (Figure S5a,e–g). As suspensor cells are known to synthesize IAA (Kawashima and Goldberg, 2010), the expression pattern of YUC9 suggests a role of YUC9 in IAA supply during early embryo development. Overall and consistent with our qRT-PCR data, these results confirm tissue specificity in YUC8 and YUC9 gene expression. In order to compare the subcellular localization of the encoded proteins, both genes were fused to the green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter gene. The resulting constructs were then used to transiently transfect Arabidopsis pavement cells by ballistic gene transfer. Confocal laser scanning microscopy revealed an exclusive cytoplasmic localization of the fusion proteins (Figure S6).

YUC8 and YUC9 contribute to MeJA-induced auxin synthesis at the organ level

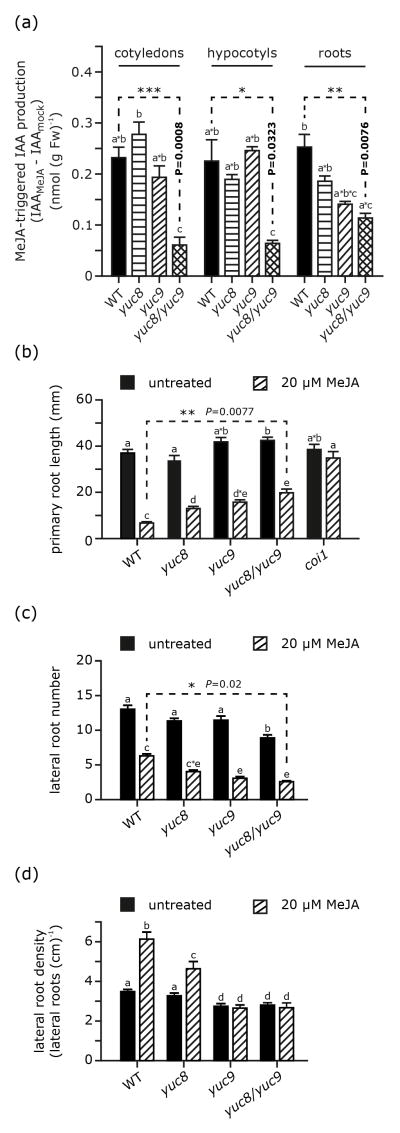

Previous studies reported that treatment with either MeJA or coronatine promotes auxin production (Dombrecht et al., 2007; Sun et al., 2009; Uppalapati et al., 2005). Hence, we next analyzed auxin levels and responsiveness to MeJA application in wild type and yuc8 and yuc9 single- and double-knockout mutants. Seven-day-old seedlings were treated for 2 hrs with either 50 μM MeJA or a control solution (0.5% methanol (v/v)) and then dissected into cotyledons, hypocotyls, and roots for separate analysis of IAA contents. Endogenous IAA levels in control mock treated seedlings were affected by YUC loss-of-function to varying degrees depending on the organ considered, with no effect in cotyledons, a decrease in hypocotyls in yuc9 and more so in yuc8, and for roots a decrease in the yuc8 mutant only (Figure S7). Combining the two mutations had no effect in cotyledons, but data for the double mutant suggested some additive effects of the yuc8 and yuc9 mutations in hypocotyls while in roots IAA levels in the double mutant mirrored those measured in yuc8. MeJA application consistently caused an elevation of IAA contents (Figure 4a), but the extent of this effect was organ- and line-dependent. While the double mutant showed reduced responsiveness to MeJA in all organs, single mutations affected responsiveness not significantly. These results indicate a role of both YUC8 and YUC9 in overall auxin homeostasis and MeJA-induced IAA production.

Figure 4.

Comparison of MeJA-induced auxin formation as well as root phenotypes in wild type and both yuc8 and yuc9 single and double mutants. (a) Auxin accumulation after MeJA treatment is given by the difference of IAA levels in mock treated samples and those in MeJA treated ones. The corresponding absolute amounts are given in Figure S7. After the treatment seedlings were dissected to separate cotyledons, hypocotyls, and roots. All organs were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. Means are given ± SE (n = 6). Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. (b) Analysis of wild type, coi1, yuc8, yuc9 and yuc8/yuc9 mutant primary root lengths. Without supplementation the primary root length of the compared lines does not significantly differ. When grown on media containing 20 μM MeJA, the examined yuc mutant roots are significantly longer than the wt ones; however, they are considerably shorter than coi1 primary roots. Means are given with their SE (n = 8–10 seedlings) (c) Relative to wild type roots, the roots of yuc8 and yuc9 single- and double-mutants show a significantly reduced number or lateral roots. Moreover, lateral root density given in number of lateral roots calculated per cm primary root is lower (d). For comparison, root systems of seedlings grown on ½ MS media or media supplemented with MeJA were analyzed. Illustrated are means ± SE (n = 15–20). Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. Mean values within a graph are significantly different [P < 0.05] where superscript letters differ.

The root response to MeJA treatment is impaired in yuc8 and yuc9

Wild-type seedlings respond to jasmonate treatment by a reduction of primary root growth (Figure 4b), consistent with earlier reports (Staswick et al., 1992). This MeJA-induced inhibition of root elongation was partially suppressed in all mutant lines (Figure 4b), most significantly so in the yuc8/yuc9 double mutant. Primary roots of MeJA-treated seedlings of this mutant were 53% shorter than corresponding untreated yuc8/yuc9 mutants, while treated yuc8 and yuc9 mutants showed 62% shorter primary roots. Under these same conditions primary roots in MeJA-treated wild-type seedlings were 82% shorter relative to the untreated wild-type plants. These gradual effects are in agreement with the differential reductions in MeJA-induced IAA synthesis in these mutants (Figure 4a).

MeJA treatment also caused a considerable reduction in the number of lateral roots, in all lines (Figure 4c). In wild type, this reduction was of relatively smaller magnitude than in the yuc8 and yuc9 single and double mutants. While in MeJA-treated wild-type seedlings the lateral root number is decreased to 48% compared to the untreated control, the reduction was more pronounced in yuc9 and yuc8/yuc9 mutants, with a decrease to 27% and 30%, respectively, relative to the corresponding untreated samples. However, when combining the observation of primary root growth inhibition with those on lateral root numbers, considering lateral root density as the index figure, we were able to detect that MeJA-treatment did not result in a diminished lateral root density, which is likely due to the pronounced inhibition of primary root growth (Figure 4d). While wild-type seedlings responded to MeJA application with a nearly 2-fold increase in lateral root density, this promoting effect was partly suppressed by the yuc8 mutation and completely abolished in by the yuc9 mutation. In both the yuc9 and yuc8/yuc9 double mutants, MeJA no more enhanced lateral root formation: lateral root density was similar on treated and untreated roots. These results show that YUC9, and possibly YUC8 are involved in mediating the promoting effect of MeJA on lateral root formation.

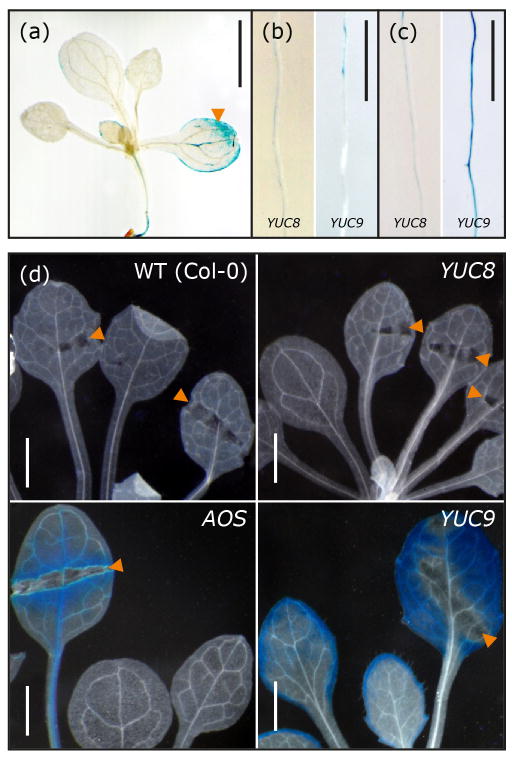

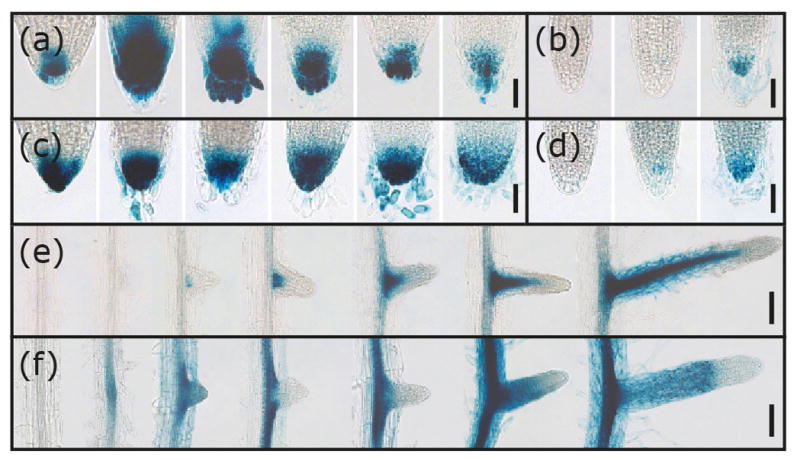

The different responses to MeJA of the yuc8 and yuc9 mutants prompted us to more closely examine the expression patterns of the two genes in roots using our GUS reporter lines. Both lines were consistently expressed in root tips (Figure 5a–d), YUC8 promoter activity was visible early during lateral root formation at the sites of primordia initiation and was very high in the vasculature of the young emerged lateral roots (Figure 5e). YUC9 expression was detectable even earlier, but was more diffuse in young lateral roots and also expressed in the vasculature of subtending roots (Figure 5f). These not totally overlapping expression pattern may suggest distinct roles of YUC8 and YUC9 in the local auxin supply through which the growth of lateral roots may be supported. Overall, these data suggest that YUC8 and YUC9 promote lateral root formation, possibly in a synergistic manner.

Figure 5.

Histochemical staining of root tips and emerging lateral roots in transgenic promoter reporter lines. Depicted are GUS-stained primary root tips of pYUC8::GUS (a) and pYUC9::GUS (c) at 1, 2, 4, 7, 10, and 14 days after germination. YUC8 (b) and YUC9 (d) promoter activity in the tips of lateral roots at 8, 12, and 14 days after emergence from the epidermis. [Scale bars, 50 μm (a–d)]. β-glucuronidase activity in pYUC8::GUS (e) and pYUC9::GUS (f) reporter lines during lateral root formation. Plants were grown sterilely on plates and then stained for reporter activity. [Scale bars: 100 μm (e–f)].

Induction of YUC9 expression by oxylipins is COI1 dependent

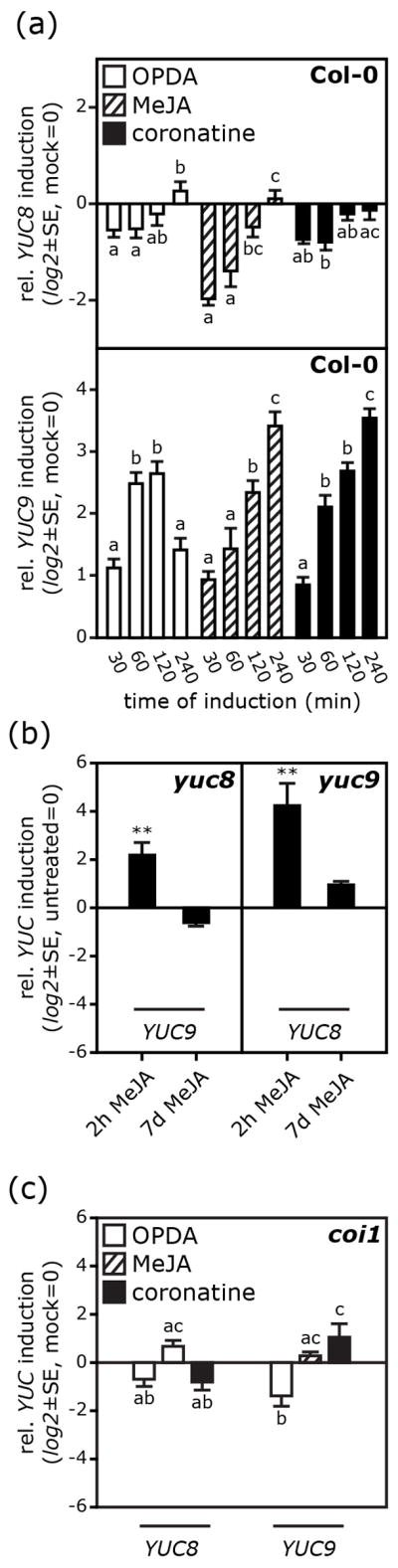

Our findings here of an increase in IAA levels after MeJA treatment as well as published gene expression datasets (Mueller et al., 2008; Pauwels et al., 2008) indicated oxylipin-dependent changes of YUC8 and YUC9 gene expression and/or activity. We therefore investigated the hypothesis that the reduced responsiveness of the yuc8 and yuc9 mutants to MeJA may reflect a role of oxylipins on the transcriptional regulation of YUC8 and YUC9. To address this, we measured YUC8 and YUC9 transcript abundance by qRT-PCR (Figure 6) following application of MeJA, OPDA or coronatine, a bacteriotoxin that mimics the bioactive jasmonate JA-Ile (Fonseca et al., 2009). In wild-type seedlings, all treatments resulted in a statistically significant reduction of YUC8 transcript levels within 30’, followed by a progressive recovery within the next 3 hrs (Figure 6a). This pattern is in line with published expression data on transcriptional responses mediated by jasmonates (Mandaokar et al., 2006), from which one can extract a similar kinetic of YUC8 transcripts. The YUC8 induction by MeJA previously observed in cell culture (Pauwels et al., 2008) may result from a transient and more general stress response and not from a specific oxylipin induction as suggested by the recent report that protoplasting of root tissue leads to a 10-fold increase of YUC8 expression (Dinneny et al., 2008). In contrast to YUC8, YUC9 transcription was not repressed but rather induced by oxylipins (Figure 6a), with a 7-fold increase in transcript levels after 120 min of OPDA treatment while MeJA and coronatine caused an even stronger induction (11- and 12-fold increase in transcript abundance 240 min post-treatment, respectively). YUC9 induction by MeJA is consistent with the increases in IAA levels and alterations of root development shown in Figure 4. The transient down-regulation of YUC8 was, however, unexpected given the apparent synergy of the two genes in increasing responsiveness to oxylipins. To further examine the interaction between YUC8 and YUC9, we asked whether a loss of either gene function might be compensated for by an up-regulation of the other one; therefore we analyzed YUC8/9 expression in the corresponding knockout background (Figure 6b). Relative to untreated seedlings YUC8 and YUC9 transcript levels were significantly more abundant after short-term MeJA treatments, which may also explain why yuc8 mutants show oxylipin-related phenotypic defects. These experiments indicate that the two genes can, at least partially, compensate for a loss of function of the other and that both genes are functionally linked. This highlights that in addition to the already reported YUC8/9 induction by high temperatures (Stavang et al., 2009), the transcriptional regulation of both genes can be considerably affected by MeJA.

Figure 6.

Oxylipin-mediated induction of YUCCA gene expression. Quantitative real time reverse transcriptase PCR for YUC8 and YUC9 gene expression in wild type (a), and both yuc8 and yuc9 (b), as well as coi1 (c) mutant seedlings after treatment under variable conditions. Seedlings were either treated with a 50 μM MeJA, 50 μM OPDA, 10 μM coronatine or control solution (½ MS media, 0.5% MeOH (v/v)). The duration of induction varied between 30 to 240 min (a) and 2 h (b,c). Additionally, a long-term treatment with 20 μM MeJA in plates was conducted (b). Then, seedlings were harvested, total RNA extracted, and transcript levels examined by qRT-PCR. Relative expression levels of the genes are normalized to levels in mock controls or untreated control samples and represent the average of three biological replicates, with error bars denoting the standard error. [Student’s t test; ** P < 0.01]. Mean values within a graph are significantly different [P < 0.05] where superscript letters differ.

JA signal transduction proceeds via the COI1 signal transduction pathway (Browse, 2009; Chini et al., 2009; Feys et al., 1994). The root phenotype of yuc8 and yuc9 mutants grown on MeJA-containing media is intermediate between that of wild type and the jasmonate-insensitive coi1 mutant (Figure 4b). The yuc8 and yuc9 single and double mutants, however, retain a residual sensitivity to MeJA, as shown by our phenotypic analyses and quantification of IAA levels, even though their responsiveness is significantly reduced (Figure 4b). To investigate whether oxylipin-dependent YUCCA expression is also governed by COI1, we treated the coi1 mutant with the various oxylipins and examined changes in YUC8 and YUC9 expression (Figure 6c). When compared to responses obtained 2 hrs after induction of wild-type plants, transcriptional responses to oxylipin treatment appeared almost entirely suppressed in the coi1 background. This suggests that the tested oxylipins most likely regulate YUC8 and YUC9 transcription through a COI1-dependent pathway (Figure 6c).

In agreement with the qRT-PCR results, the pYUC9::GUS reporter showed substantial induction in primary roots transiently treated with 50 μM MeJA, while no significant change in YUC8 promoter activity could be detected (Figure 7b,c). When plants were grown continuously on plates containing MeJA, activation of the pYUC8::GUS reporter was detectable but at an obviously lower level than that of the pYUC9::GUS reporter (Figure S8). Local application of MeJA on leaves also activated the YUC9 promoter (Figure 7a). We next examined whether the oxylipin levels produced in response to wounding (Glauser et al., 2009) were sufficient to trigger YUC8 and YUC9 promoter activation. YUC9 expression responded strongly, similar to the wound-inducible ALLENE OXIDE SYNTHASE promoter (Kubigsteltig et al., 1999), while there was no detectable reporter activity in the pYUC8::GUS lines (Figure 7d). Overall, these data indicate that YUC9- but not YUC8 expression is up-regulated by jasmonates through a COI1-dependent pathway.

Figure 7.

Induction of YUC gene expression. (a–c) GUS staining of pYUC8::GUS and pYUC9::GUS promoter reporter lines after treatment with MeJA. (a) YUC9 promoter activation 2 hours after application of 10 μL 1 mM MeJA on a single leaf (arrow). Promoter activity in primary root segments of seven-day-old pYUC8::GUS and pYUC9::GUS lines 2 hours after treatment with either a mock control (b) or with a solution containing 50 μM MeJA (c). [Scale bars: 1 cm (a–c)]. (d) Pattern of GUS activity in four-week-old sterilely grown wild type, AOS-promoter GUS line 4-1 (AOS) (Kubigsteltig et al., 1999), pYUC8::GUS (YUC8) and pYUC9::GUS (YUC9) lines 12 hours after wounding with sterile forceps (arrows). [Scale bars: 20 μm (d)].

DISCUSSION

Auxin is an essential plant growth hormone ubiquitous throughout the plant kingdom and well known to contribute to a wide array of physiological processes, acting either alone or in interaction with other phytohormones (Davies, 2010). However, the intricacies of the biosynthesis of the primary plant auxin, IAA, are yet to be fully uncovered. Currently, IAA formation is proposed to mainly proceed through four Trp-dependent pathways (Lehmann et al., 2010; Novák et al., 2012). In this context, YUCCA enzymes have received much attention since their discovery. The molecular function of YUCCA monooxygenases has been disclosed recently (Mashiguchi et al., 2011; Stepanova et al., 2011; Won et al., 2011). They are thought to play a key-role in auxin production, catalyzing the conversion of indole-3-pyruvate to IAA. YUCCA monooxygenases have been extensively studied, not only in Arabidopsis but also in tomato, maize, petunia, and rice (Expósito-Rodríguez et al., 2011; LeClere et al., 2010; Tobeña-Santamaria et al., 2002; Yamamoto et al., 2007), but despite intensive work their transcriptional regulation is still not entirely clear. Thus far, from the eleven YUCCA homologues in Arabidopsis eight have been studied in more detail (Cheng et al., 2006, 2007; Kim et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2007; Woodward et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2001). At present, only the functions of YUC7-9 have not been settled. The results described here give evidence that, as other YUCCAs, both YUC8 and YUC9 also participate in auxin production in Arabidopsis. In addition, detailed analysis of YUC8 and YUC9 gene expression during the course of plant development and in response to oxylipins demonstrates partial functional overlap between the two genes but also specificity based on their different spatio-temporal expression patterns.

Phenotypically, yuc8 and yuc9 single and double mutants grown on MS media do not substantially differ from the wild type, except for slightly shorter hypocotyls and petioles as well as a slightly reduced number of lateral roots (Figure 2, 4). The root phenotype of the yuc8 and yuc9 mutants and the localized GUS staining observed in our reporter lines (Figure 5) imply an involvement of YUC8 and YUC9 in lateral root development.

Our data also give evidence for a direct link between oxylipin signaling and auxin biosynthesis. The examined oxylipins seem to transiently repress the expression of YUC8, although YUC8 expression in the yuc9 background appears to be increased after MeJA treatment (Figure 6a,b). Also, the YUC8 promoter gets activated when seedlings are raised on plates containing MeJA (Figure S8). Similarly to the increased YUC8 response in yuc9 mutants, induction of YUC9 expression is more pronounced in yuc8 seedlings, suggesting that the two genes are functionally linked and that they can, to a certain extent, compensate for each other (Figure 6a,b). The regulatory effect of oxylipins both on YUC8 and YUC9 expression is, however, abrogated in the coi1 background, pointing to an involvement of the COI1-dependent signaling pathway in the regulation of the two genes (Figure 6a,c).

A limited number of previous studies have already provided evidence for a tight connection between JA and auxin homeostasis as well as for an involvement of the jasmonate signaling machinery in the regulation of auxin biosynthesis (for review see, Hoffmann et al., 2011). Those studies revealed a moderate impact of MeJA on YUC2 expression (Sun et al., 2009), mainly focusing on JA-mediated processes upstream of the auxin biosynthetic pathways (i.e. Trp production), auxin transport or auxin responsiveness (Dombrecht et al., 2007; Gutjahr et al., 2005; Riemann et al., 2003; Sun et al., 2011). The present results on the regulation of YUC8 and YUC9 provide novel insight into the intimate relationship between jasmonate signaling and auxin biosynthesis, pointing out that JA not only triggers substrate production for subsequent auxin synthesis (Sun et al., 2009), but also induces the formation of IAA by the direct induction of IAA synthesis-related genes.

The asa1-1 mutation appears to interfere with the enhancing effect of MeJA on lateral root formation, which is completely abolished upon treatment with more than 20 μM MeJA (Sun et al., 2009). Under these same conditions (20 μM MeJA), the number of lateral roots in yuc8 and yuc9 mutants is also substantially reduced. This effect is most significant in the yuc8/yuc9 double mutation (Figure 4d), but unlike in asa1-1 where lateral root development is totally suppressed, yuc8/yuc9 mutants still exhibit lateral roots (70% of the number of emerged lateral roots compared to untreated yuc8/yuc9 seedlings). This indicates that YUC8 and YUC9 are likely not the only components of auxin formation downstream of ASA1, linking jasmonate signaling to auxin biosynthesis.

In this context, it appears noteworthy that we did not observe an increase in lateral root number upon MeJA-treatment as point out previously (Sun et al., 2009). Rather, we detected a substantial decrease (52%) in the number of lateral roots when comparing untreated and 20 μM MeJA-treated wild-type seedlings. This discrepancy may be explained by the fact that Sun and colleagues (2009) included lateral root primordia in their assessment, while we focused on already emerged lateral roots only. On the other hand, differences in growth conditions, e.g. sugar contents in the medium, could be responsible for this inconsistency. While the asa1-1 mutation does not considerably impact on the MeJA-triggered suppression of primary root elongation, yuc8 and yuc9 mutations attenuate the inhibitory effect of MeJA on primary root elongation. This finding extends the previous observations made by Sun and colleagues (2009). Collectively, these results highlight that application of MeJA triggers an increase in IAA levels by inducing both the production of the major auxin precursor, L-Trp, and auxin synthesis.

YUC9 expression also responds to wounding and MeJA treatment in a COI1-dependent manner (Figure 6a,7). Moreover, the yuc8 and yuc9 knockouts show a root phenotype that is intermediate between the wild type and the JA-insensitive coi1 mutant, with both YUCCA gene products seemingly forming a functional unit acting synergistically on root development and root growth responses. These observations suggest that reduced primary root elongation in response to MeJA treatment is not solely due to primary JA effects, e.g. through inhibition of mitosis (Zhang and Turner, 2008). Rather, MeJA-mediated primary root growth inhibition also involves the induction of auxin synthesis and the subsequent action of this additionally formed plant hormone.

As pointed out before, the asa1-1 mutation does not result in altered primary root elongation responses to MeJA when compared to wild type plants. Thus, the inhibitory effect of MeJA on root elongation does not seem to depend on ASA1. By contrast, the examined combined yuc8 and yuc9 mutations do significantly suppress the inhibitory effect of MeJA on primary root elongation (Primary roots of MeJA-treated yuc8/yuc9 mutants appeared 2.9-fold longer than the roots of equally treated wild-type plants, P-value = 0.0077) (Figure 4b). Both ASA1 and the YUCCA genes impact on IAA levels, but ASA1 might play a more general role and act on the formation of L-Trp, a primary building block in protein synthesis. Data deposited in public databases (Genevestigator) show a medium to strong ASA1 expression in nearly all tissues and organs. In contrast, all YUCCA genes examined so far are characterized by a very tight spatio-temporal regulation of their expression. This more specific expression pattern may be the reason why yuc8 and yuc9 mutations do alter the inhibitory effect of MeJA on primary root elongation.

In summary, we propose a modified model in which the observed root growth responses are collectively mediated by JA and IAA action. Besides its primary functions, we demonstrate that JA induces the overexpression of YUC9. Together with the action of other induced enzymes, the increased YUC levels cause transient IAA overproduction. In fact, this is a good example of an indirect mode of interaction (Hoffmann et al., 2011). In turn, the increased IAA levels result in altered lateral root development and local YUC action seems to also contribute to the inhibition of primary root elongation by MeJA-induced IAA production. As phytohormones act in a dose-dependent manner, with elevated auxin concentrations exerting inhibitory effects on growth (Thimann, 1938), the increased IAA content may reinforce the jasmonate growth inhibiting effect. A transient, local increase in IAA levels may lead to local growth inhibition and also override positional auxin signals, for example, auxin gradients or local auxin maxima. In this context, it is interesting that jasmonates have been reported to interfere with auxin polar transport in a concentration dependent manner (Sun et al., 2011; Sun et al., 2009).

The relationships between JA signaling and IAA production described here might provide a further regulatory mechanism for the control of the plant responses to biotrophic or necrotrophic pathogens. The defense against these two types of pathogens is generally governed by an antagonistic relationship between salicylic acid (SA, induced by biotrophs) and jasmonic acid/ethylene (JA/ET, induced by necrotrophs and herbivores). Several studies have, however, already pointed to an interconnection between auxin and SA or JA/ET dependent pathogen responses (Chen et al., 2007; Truman et al., 2010). As the complex networks of phytohormone interaction are slowly deciphered, further insights on the sophisticated cellular processes that are affected by YUCCA enzymes will be revealed.

METHODS

Plant material and growth conditions

In this study, we analyzed the Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Col-0, the mutants coi1 (Feys et al., 1994), yuc8 and yuc9 (Tao et al., 2008), and the promoter fusions 35S::GUS (Biesgen and Weiler, 1999) as well as pAOS::GUS (Kubigsteltig et al., 1999). Seeds were germinated on solidified ½-strength MS medium supplemented with 1% sucrose in a growth chamber under controlled conditions (110 μE·m−2·s−1 photosynthetically active radiation, supplied by standard white fluorescent tubes. 8 h light at 24 °C, 16 h darkness at 20 °C).

Oxylipin treatment

Oxylipin treatment prior to the quantification of free IAA levels and RNA extraction was carried out as follows: If not stated otherwise, seedlings were grown on ½-MS medium (1% sucrose) for seven days. Next, they were transferred to either 50 μM MeJA solution (in liquid ½ MS media containing 0.5% MeOH (v/v)) or a control solution (liquid ½ MS media, 0.5% MeOH (v/v)) and incubated for the indicated period of time. In case of long-term treatments, i.e. seven days, seedlings were grown on ½-MS media (1% sucrose) containing 20 μM MeJA and directly taken from the plates. Control plants were grown on similar plates lacking MeJA. For the GUS staining of roots on plates (Figure 7b–c), seedlings of the reporter lines were grown on vertical ½-strength MS media plates supplemented with 1% sucrose. To trigger responses, 5 ml of either a mock or a 50 μM MeJA solution (vide supra) was administered to the plates. After the indicated period of time the plants were washed with ½ MS solution before they were stained for β-glucuronidase activity as explained below.

RT-PCR

Reverse-transcription was performed on total RNA isolated from wild-type plants as well as yuc8, yuc9, and coi1 mutant lines. RNA was prepared from 100 mg plant tissue by using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The mRNA was further purified using an Oligotex mRNA kit (Qiagen). First strand synthesis was performed according to the supplier’s instructions, using M-MLV-reverse transcriptase and oligo(dT)15 primer (Promega).

Expression analysis by qRT-PCR

Seedlings were grown, RNA isolated and qRT-PCR carried out as previously described (Lehmann and Pollmann, 2009). Samples were run in triplicate. Relative quantification of expression was calculated after data analysis using the Opticon monitor software (ver. 2.02.24, MJ Research) by the comparative 2−ΔΔCT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) with APT1 and UBQ10 as reference genes (Czechowski et al., 2005). For validation of reference genes and determination of amplification efficiencies the geNORM and LinRegPCR algorithms, respectively, were used (Ramakers et al., 2003; Vandesompele et al., 2002) Primer sets were as follows: APT1 (At1g27450): Pri15-Pri16; UBQ10 (At4g05320): Pri17-Pri18; YUC8: Pri19-Pri20; YUC9: Pri21-Pri22 (primer sequences are given in supporting Table S1).

GUS staining

All analyzed seedlings were grown on plates as described above. For analysis of the older plants and generative organs, plantlets were transferred into liquid MS media (1% sucrose) two weeks after germination. Plant material was pre-cleared with 90 % acetone for 0.5 hour and then stained in 50 mM citrate buffer (pH 7) containing 1 mM potassium ferrocyanide, 1 mM potassium ferricyanide, 0,1 % Triton X-100 and 1 mM 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl β-D-glucuronide cyclohexylammonium salt for 14 h at RT. Thereafter, plant material was dehydrated with an ethanol series (20%, 35%, 50%, 70%, 80%, 90% (v/v)). Prior to microscopy, GUS-stained tissues were incubated in Hoyers solution overnight (Liu and Meinke, 1998).

Microscopy

Arabidopsis leaves were transformed by particle bombardment and the microscopic analysis of the distribution of GFP-tagged fusion proteins was carried out as previously described (Pollmann et al., 2006). After incubation for 16–18 h, the YUC-GFP expressing cells were analyzed by confocal laser scanning microscopy.

GUS-stained tissues were examined with a Zeiss Axioskop 100. Images were captured on a Zeiss Axiocam MRc camera. Whole seedlings were analyzed with a Leica MZ12 microscope, and digital images were captured with a Nikon D200 camera.

Auxin quantification

Whole or dissected seedlings were immediately frozen in liquid N2. Approx. 100 mg tissue was pooled per sample and at least 3 biological replicates were harvested for each independent experiment. IAA was quantified on a Varian Saturn 2000 GC-MS/MS system as previously described (Pollmann et al., 2009).

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed with one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s-B post-hoc test to allow for comparisons among all means or with Student’s t-test when two means were compared. Statistical analyses were conducted using Prism version 5.03 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, USA).

Supplementary Material

Growth of YUC8ox and YUC9ox on 5-methyl-tryptophan-containing medium.

Transient expression of YUC8 and YUC9 in N. benthamiana.

YUC8 and YUC9 expression during seedling development.

GUS pattern in flowers and leaves.

YUC8 and YUC9 expression in siliques and ovules.

Intracellular localization of YUC8- and YUC9-GFP fusion proteins.

GC-MS analysis of IAA levels in wt and yuc mutant seedlings.

pYUC8::GUS and pYUC9::GUS lines grown on plates containing MeJA.

Generation of transgenic plants

List of primers used in this study

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by DFG grant SFB480-A10, MICINN grant BFU2011-25925, Marie-Curie grant FP7-PEOPLE-CIG-2011-303744, by a grant of the RUB to promote young academics (SP), and by NIH grant R01GM68631 (YZ). MH was supported by a fellowship from the German National Academic Foundation and a membership of the Research School of the RUB.

References

- Biesgen C, Weiler EW. Structure and regulation of OPR1 and OPR2, two closely related genes encoding 12-oxophytodienoic acid-10,11-reductases from Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 1999;208:155–165. doi: 10.1007/s004250050545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boerjan W, Cervera MT, Delarue M, Beeckman T, Dewitte W, Bellini C, Caboche M, van Onckelen H, van Montagu M, Inze D. superroot, a recessive mutation in Arabidopsis, confers auxin overproduction. Plant Cell. 1995;7:1405–1419. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.9.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böttcher C, Pollmann S. Plant oxylipins: plant responses to 12-oxo-phytodienoic acid are governed by its specific structural and functional properties. FEBS J. 2009;276:4693–4704. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browse J. Jasmonate passes muster: a receptor and targets for the defense hormone. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;60:183–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.043008.092007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Agnew JL, Cohen JD, He P, Shan L, Sheen J, Kunkel BN. Pseudomonas syringae type III effector AvrRpt2 alters Arabidopsis thaliana auxin physiology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20131–20136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704901104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Dai X, Zhao Y. Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases controls the formation of floral organs and vascular tissues in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1790–1799. doi: 10.1101/gad.1415106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Dai X, Zhao Y. Auxin synthesized by the YUCCA flavin monooxygenases is essential for embryogenesis and leaf formation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2430–2439. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.053009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chini A, Boter M, Solano R. Plant oxylipins: COI1/JAZs/MYC2 as the core jasmonic acid-signalling module. FEBS J. 2009;276:4682–4692. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czechowski T, Stitt M, Altmann T, Udvardi MK, Scheible WR. Genome-wide identification and testing of superior reference genes for transcript normalization in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:5–17. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.063743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Mashiguchi K, Chen Q, Kasahara H, Kamiya Y, Ojha S, Dubois J, Ballou D, Zhao Y. The Biochemical Mechanism of Auxin Biosynthesis by an Arabidopsis YUCCA Flavin-containing Monooxygenase. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:1448–1457. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.424077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PJ. Plant Hormones. Biosynthesis, Signal Transduction, Action! 3. Dordrecht, Boston, London: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2010. Revised. [Google Scholar]

- Dinneny JR, Long TA, Wang JY, Jung JW, Mace D, Pointer S, Barron C, Brady SM, Schiefelbein J, Benfey PN. Cell identity mediates the response of Arabidopsis roots to abiotic stress. Science. 2008;320:942–945. doi: 10.1126/science.1153795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrecht B, Xue GP, Sprague SJ, Kirkegaard JA, Ross JJ, Reid JB, Fitt GP, Sewelam N, Schenk PM, Manners JM, Kazan K. MYC2 differentially modulates diverse jasmonate-dependent functions in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2225–2245. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.048017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expósito-Rodríguez M, Borges AA, Borges-Pérez A, Pérez JA. Gene structure and spatiotemporal expression profile of tomato genes encoding YUCCA-like flavin monooxygenases: the ToFZY gene family. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2011;49:782–791. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2011.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feys B, Benedetti CE, Penfold CN, Turner JG. Arabidopsis mutants selected for resistance to the phytotoxin coronatine are male sterile, insensitive to methyl jasmonate, and resistant to a bacterial pathogen. Plant Cell. 1994;6:751–759. doi: 10.1105/tpc.6.5.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca S, Chini A, Hamberg M, Adie B, Porzel A, Kramell R, Miersch O, Wasternack C, Solano R. (+)-7-iso-Jasmonoyl-L-isoleucine is the endogenous bioactive jasmonate. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:344–350. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glauser G, Dubugnon L, Mousavi SA, Rudaz S, Wolfender JL, Farmer EE. Velocity estimates for signal propagation leading to systemic jasmonic acid accumulation in wounded Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:34506–34513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.061432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez L, Mongelard G, Flokova K, Pacurar DI, Novak O, Staswick P, Kowalczyk M, Pacurar M, Demailly H, Geiss G, Bellini C. Auxin controls Arabidopsis adventitious root initiation by regulating jasmonic acid homeostasis. Plant Cell. 2012;24:2515–2527. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.099119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutjahr C, Riemann M, Müller A, Düchting P, Weiler EW, Nick P. Cholodny-Went revisited: a role for jasmonate in gravitropism of rice coleoptiles. Planta. 2005;222:575–585. doi: 10.1007/s00425-005-0001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M, Hentrich M, Pollmann S. Auxin-oxylipin crosstalk: Relationship of antagonists. J Integr Plant Biol. 2011;53:429–445. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2011.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe GA, Jander G. Plant immunity to insect herbivores. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2008;59:41–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruz T, Szabo G, Wessendorp F, Bleuler S, Oertle L, Widmayer P, Gruissem W, Zimmermann P. Genevestigator V3: a reference expression database for the meta-analysis of transcriptomes. Adv Bioinformatics. 2008:420747. doi: 10.1155/2008/420747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull AK, Vij R, Celenza JL. Arabidopsis cytochrome P450s that catalyze the first step of tryptophan-dependent indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2379–2384. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040569997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishiguro S, Kawai-Oda A, Ueda J, Nishida I, Okada K. The DEFECTIVE IN ANTHER DEHISCIENCE1 gene encodes a novel phospholipase A1 catalyzing the initial step of jasmonic acid biosynthesis, which synchronizes pollen maturation, anther dehiscence, and flower opening in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2001;13:2191–2209. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawashima T, Goldberg RB. The suspensor: not just suspending the embryo. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazan K, Manners JM. Jasmonate signaling: Toward an integrated view. Plant Physiol. 2008;146:1459–1468. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.115717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JI, Murphy AS, Baek D, Lee SW, Yun DJ, Bressan RA, Narasimhan ML. YUCCA6 over-expression demonstrates auxin function in delaying leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot. 2011;62:3981–3992. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JI, Sharkhuu A, Jin JB, Li P, Jeong JC, Baek D, Lee SY, Blakeslee JJ, Murphy AS, Bohnert HJ, Hasegawa PM, Yun DJ, Bressan RA. yucca6, a dominant mutation in Arabidopsis, affects auxin accumulation and auxin-related phenotypes. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:722–735. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.104935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King JJ, Stimart DP, Fisher RH, Bleecker AB. A mutation altering auxin homeostasis and plant morphology in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 1995;7:2023–2037. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.12.2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubigsteltig I, Laudert D, Weiler EW. Structure and regulation of the Arabidopsis thaliana allene oxide synthase gene. Planta. 1999;208:463–471. doi: 10.1007/s004250050583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeClere S, Schmelz EA, Chourey PS. Sugar levels regulate tryptophan-dependent auxin biosynthesis in developing maize kernels. Plant Physiol. 2010;153:306–318. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.155226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann T, Hoffmann M, Hentrich M, Pollmann S. Indole-3-acetamide-dependent auxin biosynthesis: A widely distributed way of indole-3-acetic acid production? Eur J Cell Biol. 2010;89:895–905. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2010.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehmann T, Pollmann S. Gene expression and characterization of a stress-induced tyrosine decarboxylase from Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1895–1900. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CM, Meinke DW. The titan mutants of Arabidopsis are disrupted in mitosis and cell cycle control during seed development. Plant J. 1998;16:21–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandaokar A, Thines B, Shin B, Lange BM, Choi G, Koo YJ, Yoo YJ, Choi YD, Browse J. Transcriptional regulators of stamen development in Arabidopsis identified by transcriptional profiling. Plant J. 2006;46:984–1008. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mashiguchi K, Tanaka K, Sakai T, Sugawara S, Kawaide H, Natsume M, Hanada A, Yaeno T, Shirasu K, Yao H, McSteen P, Zhao Y, Hayashi K, Kamiya Y, Kasahara H. The main auxin biosynthesis pathway in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18512–18517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108434108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller S, Hilbert B, Dueckershoff K, Roitsch T, Krischke M, Mueller MJ, Berger S. General detoxification and stress responses are mediated by oxidized lipids through TGA transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2008;20:768–785. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagpal P, Ellis CM, Weber H, Ploense SE, Barkawi LS, Guilfoyle TJ, Hagen G, Alonso JM, Cohen JD, Farmer EE, Ecker JR, Reed JW. Auxin response factors ARF6 and ARF8 promote jasmonic acid production and flower maturation. Development. 2005;132:4107–4118. doi: 10.1242/dev.01955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novák O, Hényková E, Sairanen I, Kowalczyk M, Pospíšil T, Ljung K. Tissue-specific profiling of the Arabidopsis thaliana auxin metabolome. Plant J. 2012;72:523–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels L, Barbero GF, Geerinck J, Tilleman S, Grunewald W, Perez AC, Chico JM, Bossche RV, Sewell J, Gil E, Garcia-Casado G, Witters E, Inze D, Long JA, De Jaeger G, Solano R, Goossens A. NINJA connects the co-repressor TOPLESS to jasmonate signalling. Nature. 2010;464:788–791. doi: 10.1038/nature08854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauwels L, Morreel K, De Witte E, Lammertyn F, Van Montagu M, Boerjan W, Inze D, Goossens A. Mapping methyl jasmonate-mediated transcriptional reprogramming of metabolism and cell cycle progression in cultured Arabidopsis cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:1380–1385. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711203105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollmann S, Düchting P, Weiler EW. Tryptophan-dependent indole-3-acetic acid biosynthesis by ‘IAA-synthase’ proceeds via indole-3-acetamide. Phytochemistry. 2009;70:523–531. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollmann S, Neu D, Lehmann T, Berkowitz O, Schäfer T, Weiler EW. Subcellular localization and tissue specific expression of amidase 1 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta. 2006;224:1241–1253. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0304-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakers C, Ruijter JM, Deprez RH, Moorman AF. Assumption-free analysis of quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) data. Neurosci Lett. 2003;339:62–66. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(02)01423-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rampey RA, LeClere S, Kowalczyk M, Ljung K, Sandberg G, Bartel B. A family of auxin-conjugate hydrolases that contributes to free indole-3-acetic acid levels during Arabidopsis germination. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:978–988. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.039677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawat R, Schwartz J, Jones MA, Sairanen I, Cheng Y, Andersson CR, Zhao Y, Ljung K, Harmer SL. REVEILLE1, a Myb-like transcription factor, integrates the circadian clock and auxin pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:16883–16888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813035106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren C, Pan J, Peng W, Genschik P, Hobbie L, Hellmann H, Estelle M, Gao B, Peng J, Sun C, Xie D. Point mutations in Arabidopsis Cullin1 reveal its essential role in jasmonate response. Plant J. 2005;42:514–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann M, Müller A, Korte A, Furuya M, Weiler EW, Nick P. Impaired induction of the jasmonate pathway in the rice mutant hebiba. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:1820–1830. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.027490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staswick PE, Su W, Howell SH. Methyl jasmonate inhibition of root growth and induction of a leaf protein are decreased in an Arabidopsis thaliana mutant. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6837–6840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavang JA, Gallego-Bartolomé J, Gómez MD, Yoshida S, Asami T, Olsen JE, García-Martínez JL, Alabadi D, Blázquez MA. Hormonal regulation of temperature-induced growth in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2009;60:589–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova AN, Yun J, Robles LM, Novak O, He W, Guo H, Ljung K, Alonso JM. The Arabidopsis YUCCA1 flavin monooxygenase functions in the indole-3-pyruvic acid branch of auxin biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2011;23:3961–3973. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.088047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara S, Hishiyama S, Jikumaru Y, Hanada A, Nishimura T, Koshiba T, Zhao Y, Kamiya Y, Kasahara H. Biochemical analyses of indole-3-acetaldoxime-dependent auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5430–5435. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811226106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Chen Q, Qi L, Jiang H, Li S, Xu Y, Liu F, Zhou W, Pan J, Li X, Palme K, Li C. Jasmonate modulates endocytosis and plasma membrane accumulation of the Arabidopsis PIN2 protein. New Phytol. 2011;191:360–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Xu Y, Ye S, Jiang H, Chen Q, Liu F, Zhou W, Chen R, Li X, Tietz O, Wu X, Cohen JD, Palme K, Li C. Arabidopsis ASA1 is important for jasmonate-mediated regulation of auxin biosynthesis and transport during lateral root formation. Plant Cell. 2009;21:1495–1511. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szemenyei H, Hannon M, Long JA. TOPLESS mediates auxin-dependent transcriptional repression during Arabidopsis embryogenesis. Science. 2008;319:1384–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.1151461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y, Ferrer JL, Ljung K, Pojer F, Hong F, Long JA, Li L, Moreno JE, Bowman ME, Ivans LJ, Cheng Y, Lim J, Zhao Y, Ballaré CL, Sandberg G, Noel JP, Chory J. Rapid synthesis of auxin via a new tryptophan-dependent pathway is required for shade avoidance in plants. Cell. 2008;133:164–176. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thimann KV. Hormones and the analysis of growth. Plant Physiol. 1938;13:437–449. doi: 10.1104/pp.13.3.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiryaki I, Staswick PE. An Arabidopsis mutant defective in jasmonate response is allelic to the auxin-signaling mutant axr1. Plant Physiol. 2002;130:887–894. doi: 10.1104/pp.005272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobeña-Santamaria R, Bliek M, Ljung K, Sandberg G, Mol JN, Souer E, Koes R. FLOOZY of petunia is a flavin mono-oxygenase-like protein required for the specification of leaf and flower architecture. Genes Dev. 2002;16:753–763. doi: 10.1101/gad.219502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truman WM, Bennett MH, Turnbull CG, Grant MR. Arabidopsis auxin mutants are compromised in systemic acquired resistance and exhibit aberrant accumulation of various indolic compounds. Plant Physiol. 2010;152:1562–1573. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.152173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uppalapati SR, Ayoubi P, Weng H, Palmer DA, Mitchell RE, Jones W, Bender CL. The phytotoxin coronatine and methyl jasmonate impact multiple phytohormone pathways in tomato. Plant J. 2005;42:201–217. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandesompele J, De Preter K, Pattyn F, Poppe B, Van Roy N, De Paepe A, Speleman F. Accurate normalization of real-time quantitative RT-PCR data by geometric averaging of multiple internal control genes. Genome Biol. 2002;3:RESEARCH0034. doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-7-research0034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack C. Jasmonates: an update on biosynthesis, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. Ann Bot. 2007;100:681–697. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolters H, Jürgens G. Survival of the flexible: hormonal growth control and adaptation in plant development. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:305–317. doi: 10.1038/nrg2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won C, Shen X, Mashiguchi K, Zheng Z, Dai X, Cheng Y, Kasahara H, Kamiya Y, Chory J, Zhao Y. Conversion of tryptophan to indole-3-acetic acid by TRYPTOPHAN AMINOTRANSFERASES OF ARABIDOPSIS and YUCCAs in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:18518–18523. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108436108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward C, Bemis SM, Hill EJ, Sawa S, Koshiba T, Torii KU. Interaction of auxin and ERECTA in elaborating Arabidopsis inflorescence architecture revealed by the activation tagging of a new member of the YUCCA family putative flavin monooxygenases. Plant Physiol. 2005;139:192–203. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.063495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto Y, Kamiya N, Morinaka Y, Matsuoka M, Sazuka T. Auxin biosynthesis by the YUCCA genes in rice. Plant Physiol. 2007;143:1362–1371. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.091561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Turner JG. Wound-induced endogenous jasmonates stunt plant growth by inhibiting mitosis. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3699. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Li Q, Li Z, Staswick PE, Wang M, Zhu Y, He Z. Dual regulation role of GH3.5 in salicylic acid and auxin signaling during Arabidopsis-Pseudomonas syringae interaction. Plant Physiol. 2007;145:450–464. doi: 10.1104/pp.107.106021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. The role of local biosynthesis of auxin and cytokinin in plant development. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2008;11:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Christensen SK, Fankhauser C, Cashman JR, Cohen JD, Weigel D, Chory J. A role for flavin monooxygenase-like enzymes in auxin biosynthesis. Science. 2001;291:306–309. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5502.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y, Hull AK, Gupta NR, Goss KA, Alonso J, Ecker JR, Normanly J, Chory J, Celenza JL. Trp-dependent auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis: involvement of cytochrome P450s CYP79B2 and CYP79B3. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3100–3112. doi: 10.1101/gad.1035402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Growth of YUC8ox and YUC9ox on 5-methyl-tryptophan-containing medium.

Transient expression of YUC8 and YUC9 in N. benthamiana.

YUC8 and YUC9 expression during seedling development.

GUS pattern in flowers and leaves.

YUC8 and YUC9 expression in siliques and ovules.

Intracellular localization of YUC8- and YUC9-GFP fusion proteins.

GC-MS analysis of IAA levels in wt and yuc mutant seedlings.

pYUC8::GUS and pYUC9::GUS lines grown on plates containing MeJA.

Generation of transgenic plants

List of primers used in this study