Abstract

Hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS) is an uncommon hematological disorder that manifests as fever, splenomegaly, and jaundice, with hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow and other tissues pathologically. Secondary HPS is associated with malignancy and infection, especially viral infection. The prevalence of cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection in ulcerative colitis (UC) patients is approximately 16%. Nevertheless, HPS in UC superinfected by CMV is very rare. A 52-year-old female visited the hospital complaining of abdominal pain and hematochezia for 6 days. She was diagnosed with UC 3 years earlier and had been treated with sulfasalazine, but had stopped her medication 4 months earlier. On admission, her spleen was enlarged. The peripheral blood count revealed pancytopenia and bone marrow aspiration smears showed hemophagocytosis. Viral studies revealed CMV infection. She was treated successfully with ganciclovir. We report this case with a review of the related literature.

Keywords: Colitis, ulcerative; Inflammatory bowel diseases; Cytomegalovirus infections; Lymphohistiocytosis, hemophagocytic

INTRODUCTION

Hemophagocytic syndrome (HPS), also known as hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, is a rare life-threatening disease that can affect the bone marrow, lymph nodes, and cerebrospinal f luid [1,2]. This syndrome is characterized by an abnormal increase in immune cells, called histiocytes, which include monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. HPS can be classified into two forms: primary or familial HPS and secondary or reactive HPS. Primary HPS is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern and can have associated defects in the perforin, munc 13-4, and syntaxin 11 genes [2]. Secondary HPS can occur with various viral infections, including cytomegalovirus (CMV) and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [1,2]. CMV infection in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is relatively common [3], with a reported prevalence of CMV colitis in IBD of approximately 16% [3]. Although the exact mechanism of CMV in ulcerative colitis (UC) is unknown, the CMV infection in UC is associated with disease severity [3]. Some authors have reported that CMV infection increased the mortality of UC patients [4]. However, cases of HPS caused by CMV infection in UC patients are extremely rare [5]. Recently, we experienced HPS caused by CMV in a patient with UC. Therefore, we report this extremely rare case with a review of the related literature.

CASE REPORT

A 52-year-old female was admitted to hospital with fever, abdominal pain, and hematochezia for 6 days. She had been diagnosed with UC (left-side colitis) 3 years earlier and had been treated with sulfasalazine. She was in remission 5 months earlier. However, she had stopped her medication 4 months earlier on her own. On physical examination, splenomegaly was found. The blood examination showed pancytopenia (hemoglobin 6.7 g/dL, hematocrit 20.3%, total leukocyte count 400/mm3 with an absolute neutrophil count [ANC] of 64/mm3, platelets 24,000/mm3). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 120 mm/hr and the C-reactive protein 34.09 mg/dL. The serum ferritin level was elevated (956.1 µg/L). The peripheral smear showed leukopenia (neutropenia and lymphopenia), normocytic, normochromic anemia, and thrombocytopenia. A bone marrow study showed 15% hypocellularity with decreased granulopoiesis and erythropoiesis. In addition, histiocytosis with hemophagocytosis was observed (Fig. 1). Viral testing was positive for CMV serum antigenemia. Sigmoidoscopy revealed continuous hyperemic friable mucosal lesions with spontaneous bleeding (Fig. 2) and the histology showed multiple giant cells with intranuclear and cytoplasmic inclusion bodies (Fig. 3). Initially, considering the possibility of a UC flare-up, we started intravenous steroid. However, her condition did not improve. At that time, the bone marrow examination, viral assays, and sigmoidoscopic biopsy indicated CMV infection. Therefore, we started intravenous ganciclovir and tapered the steroid dose. Subsequently, her symptoms improved and the blood count normalized. She was discharged and has not relapsed during follow-up.

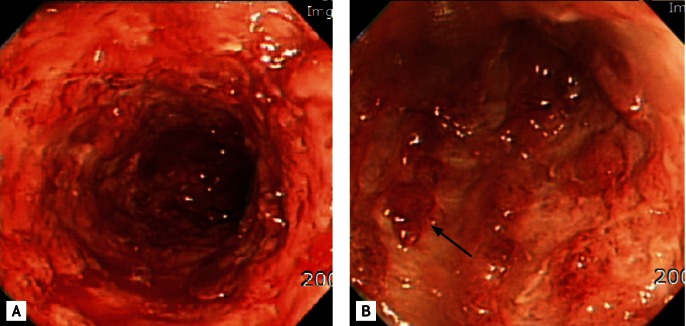

Figure 1.

Bone marrow biopsy findings. (A) The biopsy section shows hypocellularity (H&E, × 200) and (B) histiocytes containing red blood cells (black arrow), and cellular debris or particles (Wright & Giemsa stain, × 1,000).

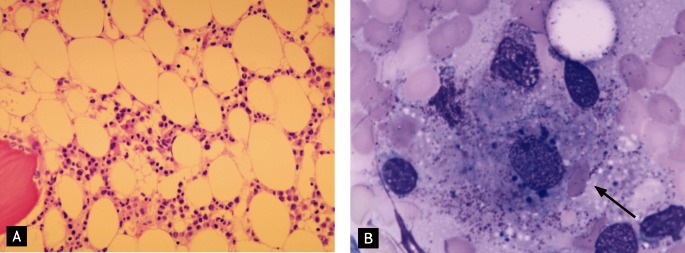

Figure 2.

Sigmoidoscopic findings. (A) A continuous hyperemic friable mucosal lesion with spontaneous bleeding is observed, and (B) multiple pseudopolyps (black arrow) are noted.

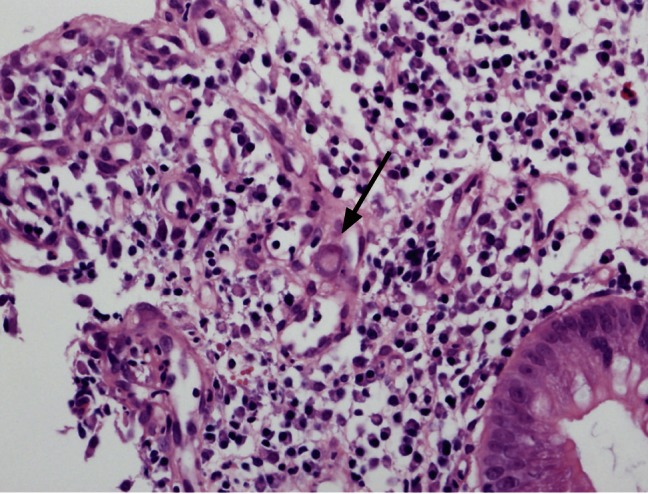

Figure 3.

The sigmoidoscopic biopsy shows giant cells with intranuclear and cytoplasmic inclusion bodies (black arrow) (H&E, × 400).

DISCUSSION

CMV is a member of the Herpesviridae family, along with herpes simplex viruses, EBV, and varicella-zoster virus. CMV is a double-stranded DNA virus that replicates in the host nucleus, causing typical pathological findings of large intranuclear inclusion bodies and smaller cytoplasmic inclusions [6]. CMV infection is common and 50% to 80% of the global population is seropositive for CMV. However, CMV infection in an immunocompetent host is usually so mild that it goes undetected clinically or is asymptomatic [6]. The virus remains within host white blood cells in a chronic latent state, and viral proliferation is prevented by host cell-mediated immunity. However, CMV can reactivate and lead to systemic infection when the host is immunocompromised, such as in transplant recipients, or patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) or hematological malignancies, or being treated with chemotherapy or corticosteroids [4,6].

In patients with IBD, CMV colitis is common and some authors have reported a 10% to 16% prevalence of CMV infection in active UC patients [3]. CMV infection in UC patients is related to severe colonic mucosal inflammation. Proinflammatory cytokines (interferon [INF]-γ and tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α) can reactivate and facilitate CMV replication in mucosal inflammation [7]. Moreover, CMV disease in active UC might be facilitated by the tropism of CMV for granulation tissue, which is seen in UC patients [8]. The role of CMV infection in UC patients is not clear. Several studies have indicated that CMV infection is associated with disease refractoriness to conventional therapy and toxic megacolon [3,4]. In addition, CMV infection might lead to resistance to conventional therapy via a reduction in either glucocorticoid receptor ligand or DNA binding [8]. In another report, CMV infection in IBD patients led to high colectomy (67%) and mortality (37%) rates [4]. However, Kim et al. [3] stated that CMV in IBD patients was an innocent bystander and might be a marker of disease severity. At endoscopy, CMV colitis resembles an IBD flare-up, with mucosal erythema, erosions, ulcerations, hemorrhage, and nodular-plaque or polypoid lesions. Therefore, a colonoscopic biopsy must be considered in patients with severe UC who are resistant to steroid therapy. The standard management of UC patients with CMV infection is conservative, with ganciclovir and partial colectomy considered when medical treatment fails [4].

HPS is a rare, often fatal disease. The clinical findings include fever, chill, gastrointestinal symptoms, pancytopenia, and hepatosplenomegaly [1,2]. Secondary or reactive HPS occurs in adults who have underlying immune dysfunction, including infection or malignancies such as NK-T cell lymphoma [1,2]. Therefore, patients with HPS should be evaluated for infection, malignancies, and autoimmune disease, such as systemic lupus erythematosus [2]. Risdall et al. [9] reported that 79% of HPS was associated with infection, frequently CMV and EBV. Virus-infected T lymphocytes undergo clonal proliferation, producing high levels of activating cytokines, including INF-γ, TNF-α, interleukin (IL)-12, and IL-18. The production of these cytokines contributes to macrophage activation and results in hemophagocytosis [10]. The wide-spread use of immunosuppressants in patients with IBD, such as corticosteroids, azathioprine, cyclosporine A, infliximab, and new biological agents, increases the risk of infection and subsequently the risk of secondary HPS [1]. Most cases of HPS in IBD develop in association with a viral infection while the patient is taking immunosuppressant medications. Nevertheless, our case was thought not to be related to immunosuppressants because the patient had not taken any such medications for 4 months. The patient was still severely immunocompromised, as the CMV infection was serious. Therefore, we postulated that the CMV infection influenced the UC flare-up and HPS directly, as immunosuppressants were not used.

To make a diagnosis of HPS, five of the following criteria should be met: 1) fever for 7 days; 2) splenomegaly; 3) unexplained progressive cytopenia of two lines: ANC < 1 × 103/µL, hemoglobin < 9 g/dL, platelet count < 100 × 103/µL; 4) hypertriglyceridemia > 265 mg/dL or hypofibrinogenemia < 1.5 g/L; 5) hyperferritinemia > 500 µg/L; 6) increased soluble CD25 > 2,400 U/mL; 7) low/absent natural killer cell activity; and 8) pathology showing hemophagocytosis (bone marrow, spleen, and lymph nodes) [2]. Our patient met five of the eight criteria: fever, splenomegaly, cytopenia, elevated ferritin, and pathology showing hemophagocytosis. No treatment for secondary HPS has been established. Most guidelines recommend supportive care, cessation of any causative immunosuppressive agents, and specific treatments targeting the underlying pathogen. In a CMV infection, immunoglobulin with ganciclovir is useful [1].

In conclusion, it is important to perform a colonoscopic biopsy to confirm CMV infection in a patient who is resistant to the conventional management of an IBD flare-up, because the endoscopic findings of CMV colitis in this case resembled an IBD flare-up. In addition, patients with pancytopenia, fever, and splenomegaly should be studied further to rule out the possibility of secondary HPS.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article is reported.

References

- 1.James DG, Stone CD, Wang HL, Stenson WF. Reactive hemophagocytic syndrome complicating the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:573–580. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000225333.83861.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janka GE. Hemophagocytic syndromes. Blood Rev. 2007;21:245–253. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JJ, Simpson N, Klipfel N, Debose R, Barr N, Laine L. Cytomegalovirus infection in patients with active inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1059–1065. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Begos DG, Rappaport R, Jain D. Cytomegalovirus infection masquerading as an ulcerative colitis flare-up: case report and review of the literature. Yale J Biol Med. 1996;69:323–328. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koketsu S, Watanabe T, Hori N, Umetani N, Takazawa Y, Nagawa H. Hemophagocytic syndrome caused by fulminant ulcerative colitis and cytomegalovirus infection: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1250–1253. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0543-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosugi I. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Uirusu. 2010;60:209–220. doi: 10.2222/jsv.60.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soderberg-Naucler C, Fish KN, Nelson JA. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha specifically induce formation of cytomegalovirus-permissive monocyte-derived macrophages that are refractory to the antiviral activity of these cytokines. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:3154–3163. doi: 10.1172/JCI119871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cottone M, Pietrosi G, Martorana G, et al. Prevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in severe refractory ulcerative and Crohn's colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:773–775. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Risdall RJ, McKenna RW, Nesbit ME, et al. Virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome: a benign histiocytic proliferation distinct from malignant histiocytosis. Cancer. 1979;44:993–1002. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197909)44:3<993::aid-cncr2820440329>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisman DN. Hemophagocytic syndromes and infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:601–608. doi: 10.3201/eid0606.000608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]