Abstract

The nervous and vascular systems are both exquisitely branched and complicated systems and their proper development requires careful guidance of nerves and vessels. The recent realization that common ligand-receptor pairs are used in guiding the patterning of both systems has prompted the question of whether similar signaling pathways are used in both systems. This review highlights recent progress in our understanding of the similarities and differences in the intracellular signaling mechanisms downstream of semaphorins, ephrins, and VEGF in neurons and endothelial cells during neural and vascular development. We present evidence that similar intracellular signaling principles underlying cytoskeletal regulation are used to control neural and vascular guidance, while the specific molecules used in neurons and endothelial cells are often different.

The development and proper function of the nervous and vascular systems are essential for the survival of all higher organisms. Interestingly, these two systems share many similarities. Developmentally, they are the first specific tissue systems to appear in embryonic development, and both continue to dynamically remodel throughout life. Anatomically, they are both highly branched and complicated networks, yet both are remarkably reproducible from one individual to another. Functionally, they both extend to every part of the organism and either coordinate function or provide oxygen and nutrients. They also regulate each other’s function; for example, arteries supply neurons with oxygenated blood and nerves control blood vessel dilation and contraction. In addition, in the periphery, blood vessels and nerves often run in parallel [1].

This similarity also extends to the cellular level. Neurons explore their environment and find targets using growth cones (dynamic palmate structures at the leading edge of the growing axon that can sense and react to environmental cues). Similarly, vessels use specialized tip cells, which are located at the front of navigating blood vessels and are morphologically and functionally similar to the axonal growth cone [2]. Actin filaments and microtubules are the major cytoskeletal components that determine the structure and motility of growth cones and tip cells, thereby controlling axon guidance and endothelial cell migration (Box 1).

Box 1: Cytoskeletal reorganization in neuronal growth cone dynamics, dendritic spine morphorgenesis, and endothelial tip cell motility.

Actin filaments are a major cytoskeletal component that determines the structure and motility of growth cones and tip cells and are organized into two distinct morphological elements: dense, fingerlike projections called filopodia and loosely interwoven, veil-like structures termed lamellipodia. In addition, microtubules are the other major structural element of growth cones and tip cells. Microtubules dynamically extend and retract along the filopodial actin filaments.

Cytoskeletal reorganization is the central event for axon guidance, dendritic spine morphogenesis, and endothelial cell migration. The leading edge of the growth cone senses the attractive or repulsive cues, which, through various signaling pathways, changes the balance between the polymerization of actin at its barbed ends and the retrograde flow of the entire filament. In the case of chemoattraction, the polymerization of actin drives the filopodia and lamellipodia in the direction of attractive cues. Once the initial filopodial contact is established, microtubules follow and form stable bundles in the axon shaft. Whether the function of microtubules is only to stabilize the extending axons is still controversial. In the case of chemorepulsion, repulsive signals initiate the cytoskeletal reconfigurations necessary for redirecting the axonal path by inducing the focal loss of actin bundles followed by the focal loss of dynamic microtubules [88]. Like growth cones, tip cells are highly dynamic structures that use lamellipodia and filopodia to detect the extracellular environment and lead the growing vessel in the correct direction [2]. The movement of these protrusions is driven by actin polymerization in the direction of attractive cues. For example, Netrin receptor Unc5b is expressed in the endothelial tip cells. Unc5b knock-out mice exhibit excess filopodial extension. Exposure of tips cells to Netrin-1 induces rapid filopdial retraction and backward movement of the cells [89]. In addition, endothelial cells can be stabilized by adherence to the extracellular matrix (ECM) or to adjacent cells. These adhesions serve as traction sites as the cell moves forward over them, and are disassembled at rear of the cell, allowing it to detach [2, 90]. Thus, in order to understand the guidance mechanisms behind growth cone and tip cell movement, it is important to determine how guidance cues are transduced and affect actin and microtubule dynamics and organization. Dendritic spines are specialized post-synaptic structures which emanate from the dendritic shaft. They are formed from dendritic filopodia, small, actin-rich protrusions which are rapidly formed and retract from the dendritic shaft. Similarly to axons, actin rearrangements are critical for this rapid filopodial formation/retraction. Actin treadmilling, with disassembly of fibers closer to the spine shaft and polymerization at the tip of the filopodia/spine, has been observed in filopodia. Long, thin filopodia are remodeled into shorter and stubbier mature spines in development, a process which could involve the nucleation and branching of actin. Rho family GTPases have been found to link intracellular signals to actin dynamics within the spine and depending on which family members are activated, spines can retract, elongate, or change shape.

Recently, it has become clear that neuronal and vascular morphogenesis is also tightly interwoven at the molecular level. Thus far, four major axon guidance molecule families (ephrins, semaphorins, slits, and netrins), which are widely expressed by multiple cell types and exert diverse biological functions, have been implicated in angiogenesis [1, 3–6]. In addition, VEGF, a well-known angiogenic factor, has been shown to participate in the function of the nervous system. This raises the question of whether these molecules use the same downstream signaling pathways to exert their effects on neurons and endothelial cells to control axon and vascular guidance. This review highlights recent progress in our understanding of the similarities and differences in the intracellular signaling mechanisms utilized by semaphorins, ephrins, and VEGF in neurons and endothelial cells. Currently less is known about the intracellular signaling of slits and netrins in endothelial cells, for discussion of their dual role in axon and vascular guidance, see review [1, 3–5].

Semaphorins

The semaphorins are the largest family of guidance molecules containing both secreted molecules capable of long-range diffusion and membrane-bound proteins that function as short-range guidance cues [7] (Box 2) . Great progress has been made recently on the semaphorin down-stream signaling in neurons and endothelial cells. Here we will discuss two semaphorins, the transmembrane Sema4D and the secreted Sema3A, and compare their signaling mechanisms in the nervous and vascular systems. Short descriptions of the proteins mentioned in each section can be found in Table 1.

Box 2: Background about the Semaphorin, Ephrin, and VEGF families of proteins.

The semaphorins are the largest family of guidance molecules composed of 8 classes with a total of 29 members, containing both secreted molecules capable of long-range diffusion and membrane-bound proteins that function as short-range guidance cues [7]. Semaphorins signal through multimeric receptor complexes. Secreted class 3 semaphorins generally signal through a holoreceptor composed of the ligand-binding subunit Npn (Neuropilin) and the signal transducing subunit PlexinA receptors to induce growth cone guidance, with the exception of Sema3E, which can signal through a Plexin-D alone [40]. Most of the membrane-bound semaphorins can signal directly through plexins. Plexins make up a family of large transmembrane proteins. PlexinA was first identified as the Drosophila class I and II semaphorin receptor, but plexins are now understood to be a critical receptor for many other members of the semaphorin family. Semaphorins were initially implicated as axon guidance cues but are now known to play broader roles in morphogenesis, including vascular development and tumor angiogenesis [7, 42, 43].

There are two families of ephrins; the ephrin-A family is GPI-linked and consists of five members, while ephrin-Bs are transmembrane and the family is made up of three proteins. Their corresponding Eph receptors, the nine EphA receptors and five EphB receptors, are receptor tyrosine kinases. With very few exceptions, ephrin-As bind promiscuously to EphA receptors, while the ephrin-Bs bind to EphB receptors. Among the domains present on the Eph receptors are an extracellular ephrin binding domain and intracellular kinase and PDZ-binding domains. Interestingly, since ephrin ligands are either membrane-tethered or transmembrane proteins, Eph-ephrin signaling can be bidirectional. When the signaling proceeds through the Eph receptor, this is termed “forward” signaling. When the signaling is mediated through the ephrin ligand, this is referred to as “reverse” signaling. While Eph-ephrin signaling was first described as being important in axon repulsion, ephrins have been implicated in a wide variety of biological processes such as cell survival, proliferation, and migration. For a review of ephrin function, see [91].

The VEGF family is comprised of five classes—VEGF-A, -B, -C, -D and PLGF (placental growth factor). Alternate splicing of VEGF-A generates three different sized proteins—VEGF121,VEGF165, and VEGF180, which have different receptors and functional significance. VEGF165 has been shown to be most important for many aspects of embryonic development and will be the variant referred to throughout this review. VEGF plays crucial roles during the development of the vascular system through its tyrosine kinase receptors, VEGFR1 (also called Flt1), which regulates monocyte migration, VEGFR2 (also called Flk1), which regulates many aspects of endothelial cell biology like migration, proliferation, and permeability, and VEGFR3, which is important for the development of the lymphatic system. In addition to these receptors, the VEGFR2 co-receptor Neuropilin-1 (Npn-1) binds both VEGF121 and VEGF165 [35, 39]. Endothelial tip cells migrate towards higher concentrations of VEGF, while the endothelial stalk cells that follow the tip cells proliferate in response to high VEGF concentrations [2]. Several recent studies have also revealed the role of VEGF-regulated- Dll4-Notch signaling in suppressing endothelial tip cell formation. During vessel sprouting, VEGF induces the expression of the Notch ligand Dll4 (Delta-like ligand (Dll)4). Higher Dll4 expression in the leading tip cells activates Notch in the adjacent stalk cells and suppresses them from become tip cells. This results in the proper ratio between tip and stalk cells required for correct sprouting and branching patterns. In addition, Dll4-Notch signaling also provides a negative feedback loop to prevent overexuberant angiogenic sprouting, promoting the timely formation of a well differentiated vascular network [92].

Table.

Description of the signaling molecules involved in semaphorin, ephrin, and VEGF pathways

| Abbreviated name |

Full name | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Akt | Protein kinase B | General protein kinase. Signals downstream of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) to mediate the effects of various growth factors. |

| Cdk5 | cyclin-dependent kinase 5 | A serine/threonine kinase; initially identified for their involvement in cell cycle progression. Most studied functions were in nervous system. |

| Cofilin | Actin binding protein which disassembles actin filament | |

| CRMP2 | collapsing-response-mediator protein2 | Tubulin binding protein which stimulates microtubule assembly; necessary for Sema3 signaling and subsequent remodeling of the cytoskeleton. |

| CXCR4 | Chemokine receptor 4 | A receptor for SDF-1. |

| ECM | extracellular matrix | The extracellular part of animal tissue that usually provides structural support to the cells in addition to performing various other important functions. |

| Ephexin | A RhoGEF which activates Rho by converting Rho-GDP to Rho-GTP. | |

| ErbB2 | Human Epidermal growth factor Receptor 2 | Receptor tyrosine kinase. |

| ERM | Ezrin–radixin–moesin (ERM) proteins | A class of proteins that mediates linkage between the plasma membrane and the F-actin cytoskeleton and regulates filopodia. |

| FAK | Focal Adhesion Kinase | A focal adhesion-associated protein kinase involved in cellular adhesion and spreading processes. |

| FARP2 | FERM, RhoGEF and pleckstrin domain-containing protein 2 | A Rac1GEF which activates Rac1 by converting Rac1-GDP to Rac-GTP. |

| Fer | fer (fps/fes related) tyrosine kinase | A member of the FPS/FES family of non-transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinases. It regulates cell-cell adhesion and mediates signaling from the cell surface to the cytoskeleton via growth factor receptors. |

| Fes | c-fes/fps protein | Fes has tyrosine-specific protein kinase activity that is required for the maintenance of cellular transformation. |

| Fyn | A member of the Src family of nonreceptor tyrosine kinases. | |

| Girdin | (also known as) Girders of actin filament | Actin binding protein. |

| Grb4 | SH2/SH3 domain containing adaptor protein. | |

| GRIP1 | Glutamate receptor interacting protein 1 | An adaptor protein which contains seven PDZ domains. |

| GSK3 | glycogen synthase kinase 3 | Serine/threonine protein kinase. The phosphorylation of target proteins by GSK-3 usually inhibits them. |

| Kalirin | A RhoGEF which activates Rho by converting Rho-GDP to Rho-GTP | |

| L1 | L1 cell adhesion molecule | Cell adhesion molecule with an important role in the development of the nervous system. |

| LIMK | LIM motif-containing protein kinase | Protein kinase which regulates actin filament dynamics. Phosphorylates and inactivates the actin binding/depolymerizing factor Cofilin, thereby stabilizing the actin cytoskeleton. |

| Met | mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor | Receptor for hepatocyte growth factor and scatter factor. Has a tyrosine-protein kinase activity. |

| Nck1/2 | non-catalytic region of tyrosine kinase adaptor protein 1 (and 2) | SH2/SH3 domain containing adaptor protein. |

| Npn-1 | neuropilin 1 | Transmembrane co-receptor for both vascular endothelial growth factor and semaphorin family members. Npn-1 plays versatile roles in angiogenesis, axon guidance, cell survival, migration, and invasion. |

| p75-NTR | p75 neurotrophin receptor | A low-affinity receptor for neurotrophins with wide-ranging roles in nervous system development and tumor growth |

| PAK | p21 protein (Cdc42/Rac)-activated kinase | Activated by Cdc42 and Rac1. Involved in dissolution of stress fibers and reorganization of the cytoskeleton. |

| PDZ-RhoGEF | PDZ domain containing Rho-guanine nucleotide exchange factor | A RhoGEF which activates Rho by converting Rho-GDP to Rho-GTP, and also contains PDZ domain. |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide Kinase-3 | PI 3-kinases have been linked to an extraordinarily diverse group of cellular functions. Many of these functions relate to the ability of class I PI 3-kinases to activate protein kinase B (PKB, aka Akt). |

| PIPKIγ661 | type-I phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase γ661 | An enzyme that generates PI4,5P2, targeted to and regulating focal adhesions. |

| PLC-γ | phospholipase-c gamma | Catalyzes the formation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol from phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, which then have multiple roles in intracellular signaling events. |

| PTEN | phosphatase and tensin homolog | Antagonizes the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway by dephosphorylating phosphoinositides and thereby modulating cell cycle progression and cell survival. |

| Pyk2 | FAK-related proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 | A non-receptor tyrosine kinase. |

| Rac1GEF | Rac1-guanine nucleotide exchange factor | Positive regulator of Rac1 that converts inactive Rac1-GDP to active Rac1-GTP. |

| ROCK | Rho-kinase | A serine/threonine-specific protein kinase which is activated by GTP-bound RhoA. |

| R-RasGAP | R-Ras GTPase-activating proteins | Negative regulator of Ras that converts active Ras-GTP to inactive Ras-GDP. |

| SDF-1 | Stromal derived factor 1 | A chemoattractant chemokine involved in cell migration. |

| Shb | Src homology 2 domain-containing transforming protein B | Adaptor protein. |

| Tiam1 | T-cell lymphoma and metastasis 1 | A Rac1 GEF which activated Rac1 by converting Rac1-GDP to Rac1-GTP. |

| TSAd | (also known as) SH2 domain protein 2a | Adaptor protein. |

| α2-chimaerin | A RacGAP which inactivates Rac by converting RacGTP to RacGDP. |

Sema4D signaling in the nervous and vascular systems

Sema4D binds to Plexin-B1, inducing growth cone collapse and preventing axon outgrowth in cultured E18.5 hippocampal neurons [8–10], an effect that is blocked in neurons from Plexin-B1 knockout mice [11]. In the vascular system, Sema4D increases endothelial cell migration [12] and is possibly involved in tumor-induced angiogenesis [13]. Sema4D or Plexin-B1 knockout mice display defects in the ability of cancer cells to generate tumor masses and metastases [14], and detailed in vivo histological analysis of the vascular and nervous systems in both knockout mice is warranted.

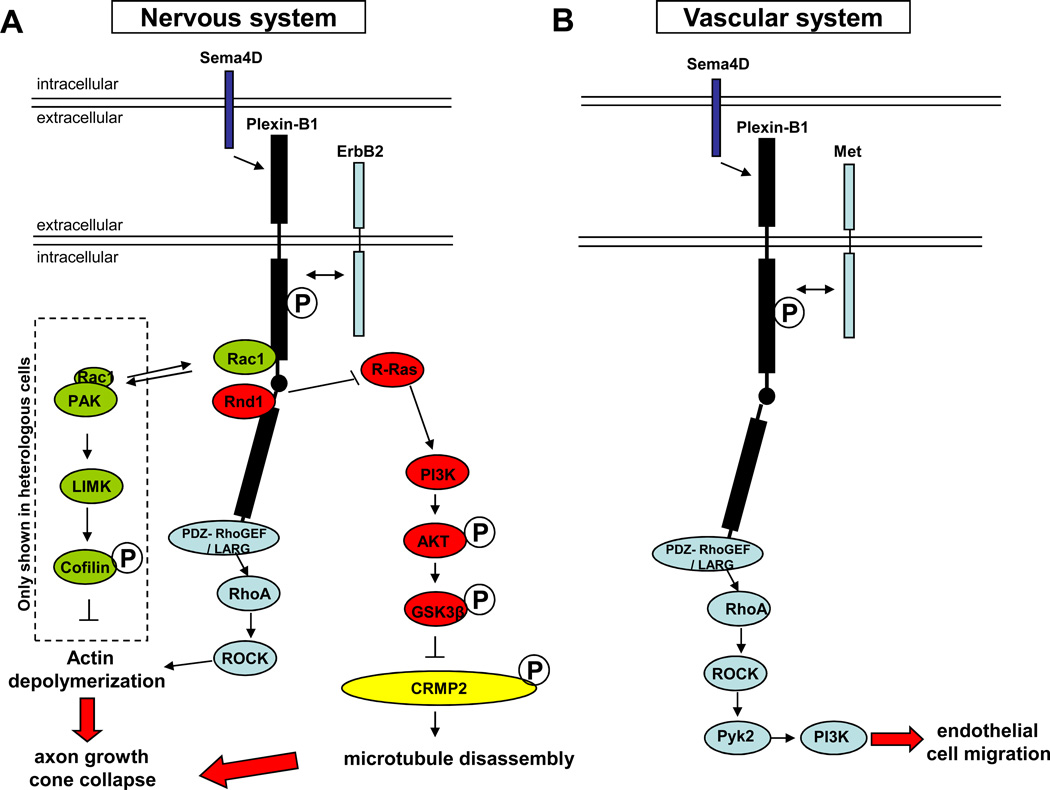

The small GTPase RhoA is a central player in Sema4D–Plexin-B1 signaling in both neurons and endothelial cells. GTPases are small proteins that participate in many cellular processes. They are present in an active GTP-bound form and an inactive GDP-bound form. Two types of proteins regulate their function—GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) stimulate hydrolysis of GTP into GDP, thus inactivating the GTPase, whereas guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) replace GDP with GTP, thus activating the GTPase. In both cultured hippocampal neurons and endothelial cells, Plexin-B1 binds to PDZ-RhoGEF and leukemia-associated RhoGEF (LARG) through a C-terminal PDZ binding motif (Figure 1A,B). Upon Sema4D binding, a receptor tyrosine kinase (ErbB2 in neurons and Met in endothelial cells [18,19]) binds to and subsequently phosphorylates Plexin-B1, activating PDZ-RhoGEF and LARG, and increasing active RhoA and ROCK (RhoA-activated kinase) [15]. The activation of RhoA/ROCK then induces the collapse of cultured hippocampal neuron growth cones and promotes endothelial cell migration and vessel formation [12] through different downstream signaling pathways.

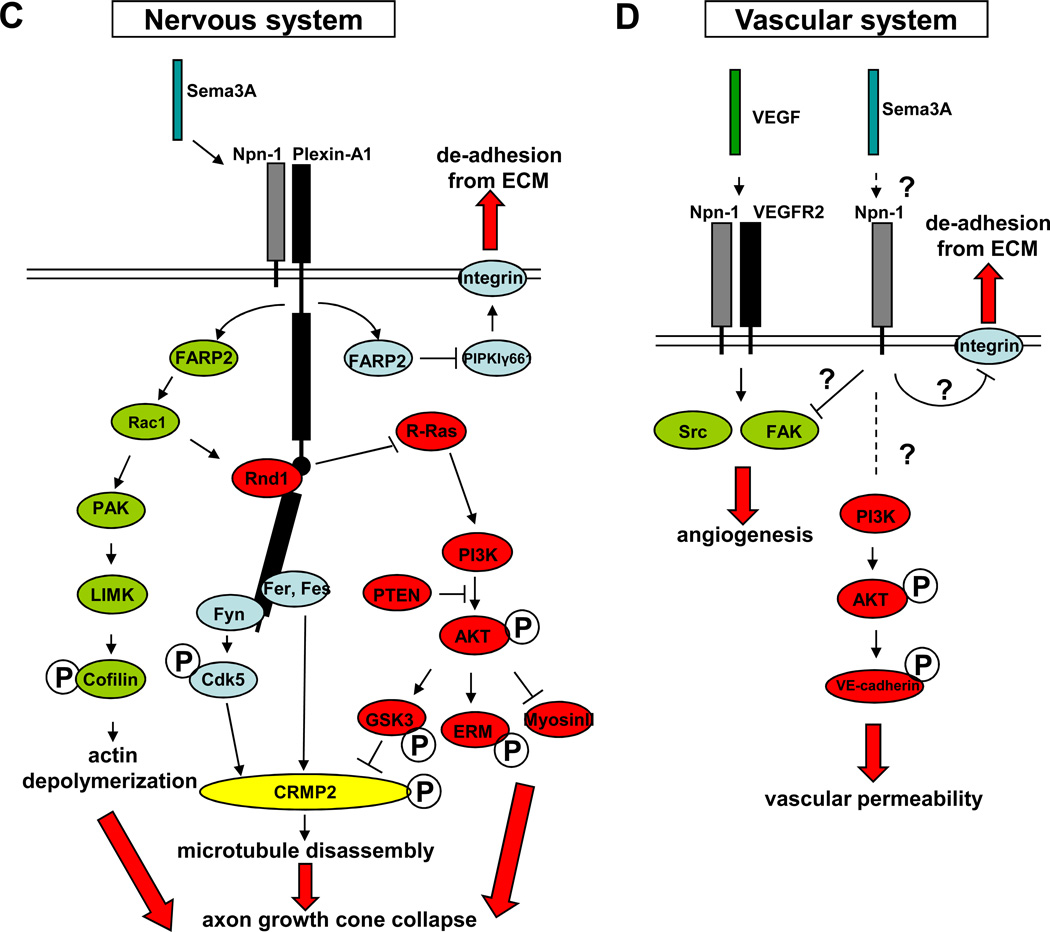

Figure 1. Sema4D and Sema3A signaling in the nervous and vascular systems.

Plexin-B1 and Plexin-A1 are shown in black, with the intracellular C1 and C2 domains represented by black rectangles and the linker region in between as a black circle. A: Sema4D signaling in the nervous system. Proteins in the R-Ras pathway are shown in red: in the presence of Sema4D, Rnd1 is recruited to Plexin-B1. Plexin-B1 R-RasGAP activity is activated and downregulates the active form of R-Ras. The decrease of active R-Ras inhibits PI3K-Akt activity, decreasing GSK3β phosphorylation and activing it. GSK3β then phosphorylates and deactivates CRMP2 and causes microtubule disassembly. Proteins in the RhoA pathway are shown in blue: in the presence of Sema4D, receptor tyrosin kinase ErbB2 binds and subsequently phosphorylates Plexin-B1 (as indicated by the double-headed arrow) and then activates PDZ-RhoGEF/LARG, which associates with Plexin-B1. PDZ-RhoGEF/LARG activates RhoA, causing actin depolymerization through ROCK. Proteins in the Rac1 pathway are shown in green: Upon Sema4D binding, activated Plexin-B1 competes for active Rac1 with PAK. The shift on the equilibrium between Plexin-B1- and PAK- bound Rac1 results in decrease of PAK activity, LIMK activity, and Cofillin phosphorylation, thus causing actin depolymerization. This pathway so far has only been shown in heterologous cells, as indicated by the dashed box. Both the actin depolymerization and microtubule disassembly lead to axon growth cone collapse. B: Sema4D signaling in the vascular system. Proteins in the RhoA pathway are shown in blue: in the presence of Sema4D, the receptor tyrosine kinase Met binds and phosphorylates Plexin-B1 (as indicated by the double-headed arrow) and then activates PDZ-RhoGEF, which activates RhoA and leads to endothelial cell migration through the ROCK, Pyk2, and PI3K pathway. It is not clear how this pathway affects actin dynamics or microtubule dynamics in vascular system. C: Sema3A signaling in the nervous system. Rac1 regulating proteins are shown in green: in the presence of Sema3A, FARP2 is released from PlexinA1 and actives Rac1. Rac1 then activates PAK and LIMK and, as a result, phosphorylates Cofilin, which finally causes actin depolymerization. R-Ras regulating proteins are shown in red: in the presence of Sema3A, Rac1 facilitates Rnd1 recruitment to PlexinA1, which induces PlexinA1’s R-RasGAP activity and downregulates active R-Ras. Decrease of active R-Ras downregulates PI3K-Akt activity and leads to axon growth cone collapse through 3 different pathways: reduced phorporylatesGSK3β, reduced phosphorylation of ERM, and activation of myosinII. Kinases are shown in blue: in the presence of Sema3A, FARP2 inhibits PIPKIγ661 and suppresses integrin-induced adhesion. Fer and Fes are activated upon Sema3A binding to Plexin-A1 and phosphorylate and inactivate CRMP2, which leads to microtubule disassembly. Fyn is also activated after its binding to PlexinA1 and inactivates CRMP2 by phosphorylating and activating Cdk5. Both actin depolymerization and microtubule disassembly lead to axon growth cone collapse. D: Sema3A signaling in the vascular system. Sema3A, through an unknown mechanism (possibly through Npn-1 and/or a co-receptor, shown as a dashed line and question mark), inhibits VEGF-induced activation of Src and FAK and contributes to angiogenesis. Sema3A may also function through Npn-1 to inhibit integrin-mediated adhesion of endothelial cells to the ECM. Sema3A can induce VE-cadherin phosphorylation and causes vascular permeability through unknown mechanisms (indicated by question marks), in which PI3K-Akt is involved.

In addition to the different upstream regulators of RhoA activation in neuron and endothelial cells, i.e. ErbB2 and Met, respectively, the signals downstream of RhoA are also distinct in the two systems. Downstream of RhoA, endothelial cells have a unique pathway through Pyk2, a non-receptor tyrosine kinase that can be activated by RhoA/ROCK. Activation of Pyk2 triggers the PI3K-Akt pathway and leads to cytoskeletal reorganization and endothelial cell migration [16] (Figure 1B).

Sema4D–Plexin-B1 signaling in neurons also involves two small GTPases not yet shown to be critical for this signaling in endothelial cells (Figure 1A). One of these is R-Ras. Plexin-B1 has two conserved R-RasGAP homology motifs located in its C1 and C2 domains, which are autoinhibited in the absence of Sema4D [9]. In cultured hippocampal neurons, upon Sema4D treatment, Rnd1, a constitutively active small GTPase, is recruited to Plexin-B1 and induces the R-RasGAP activity of Plexin-B1 by releasing the inhibitory interaction between the C1 and C2 domains in the intracellular region [8, 9] leading to conversion of active R-Ras-GTP to inactive R-Ras-GDP. Sema4D-induced down-regulation of R-Ras activity dephosphorylates PI3K/Akt and activates GSK3β. GSK3β then phosphorylates and inactivates CRMP2, causing hippocampal neuron growth cone collapse [10, 17]. CRMP2 is a member of collapsing-response-mediator protein family, which stimulates microtubule assembly in neurons [17]. The second small GTPase involved in Sema4D–Plexin-B1 signaling in neurons is Rac1, a member of the Rho small GTPase family. Sema4D binding to Plexin-B1 promotes the binding of active Rac1 to Plexin-B1, which results in a reduction of the amount of active Rac1 bound to the p21-activated kinase (PAK) and therefore reduces PAK activity [18, 19]. In cultured fibroblasts, Rac1 activates LIMK (LIM-kinase) via PAK and LIMK phosphorylates and inactivates Cofilin, an actin severing protein. Thus, Sema4D binding to Plexin-B1 sequesters active Rac1 by down-regulating PAK-LIMK activity, thus releasing the inhibition of Cofilin, and causing growth cone collapse [18, 19] (Figure 1A). It will be interesting to test whether comparable mechanisms involving R-Ras and/or Rac1 exist in Sema4D–Plexin-B1 signaling in the vascular system.

Sema3A signaling in the nervous and vascular systems

Sema3A was the first semaphorin identified in vertebrates and genetic studies have implicated it in a variety of neural wiring processes including axon guidance, fasciculation (axon bundling), branching, pruning, dendrite development, and neuronal migration [7]. In neurons, it is well established that Sema3A signals through the Npn-1–PlexinAs complex to induce cytoskeletal reorganization and growth cone collapse. Both Sema3A null mutant embryos and Npn-1Sema- knock-in mutants, in which Sema3A–Npn-1 binding is selectively abolished due to an engineered mutations in the Sema3A binding site of Npn-1, have severe abnormalities in many CNS and PNS axon projections [7].

In neurons, similarly to Sema4D, small GTPases (Rac1 and R-Ras) and kinases are involved in Sema3A signaling. For Rac1, the same pathway of Rac1-PAK-LIMK-Cofilin activation that is used in Sema4D also participates in Sema3A signaling. However, in contrast to the Sema4D signaling pathway, Rac1 activity is enhanced immediately in the presence of Sema3A. Rac1 activation is achieved by FARP2, a Rac1GEF, which is released from PlexinA and activated upon Sema3A binding (Figure 2A) [20]. Another difference between Sema3A and 4D signaling is that an as yet unknown factor downstream of Sema3A can re-activate Cofilin after its inactivation by LIMK [20]. Therefore, even though Sema3A increases Rac1 activity, the end result of Rac1 signaling is still growth cone collapse.

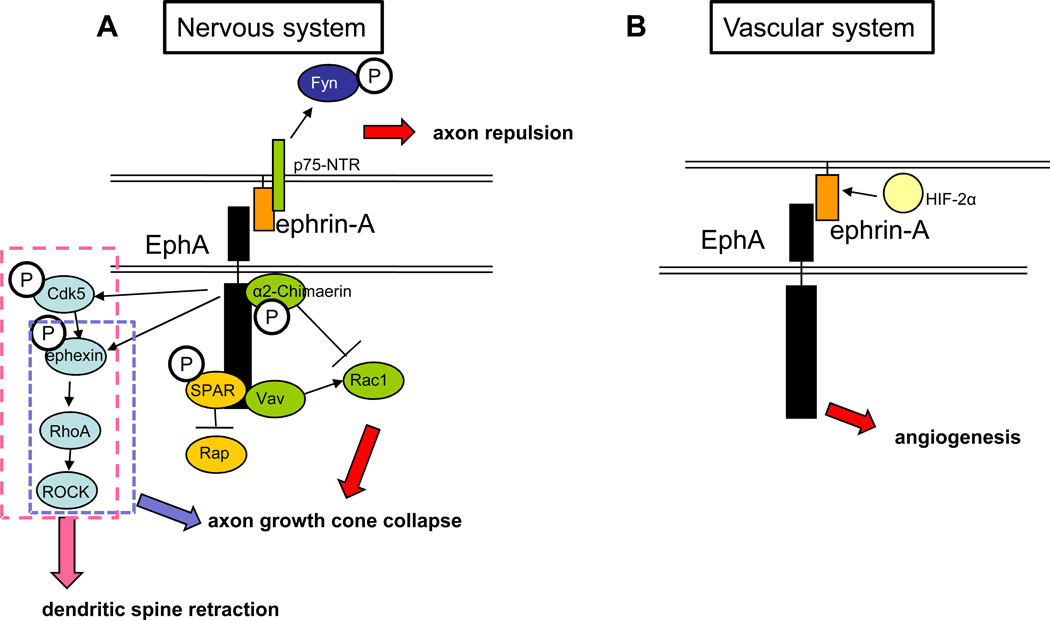

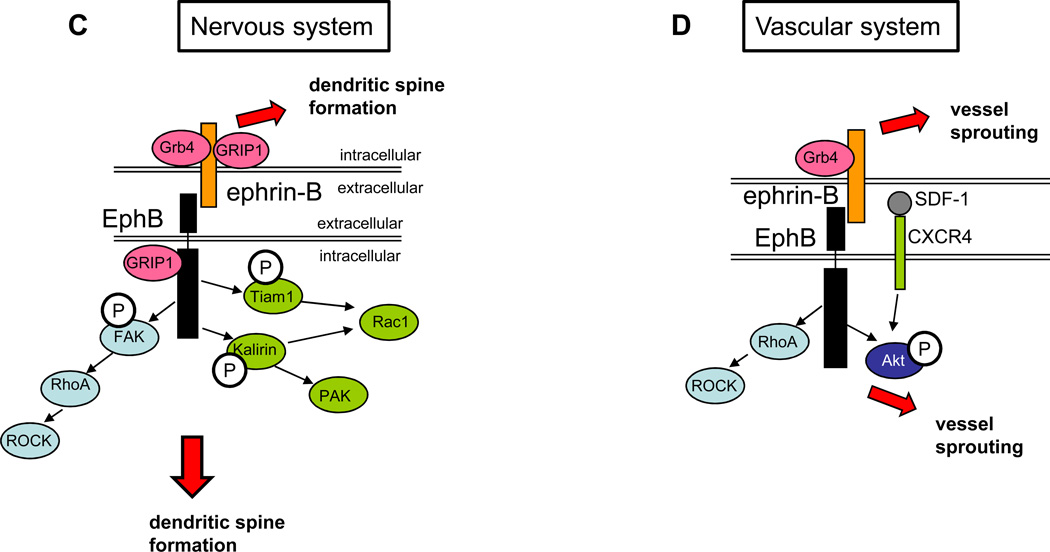

Figure 2. Ephrin-Eph signaling in the nervous and vascular systems.

A: ephrin-A-EphA signaling in the nervous system. The Rap pathway is shown in yellow: EphA activation leads to tyrosine phosphorylation of SPAR, a RapGAP that binds to EphA4 through its PDZ domain. SPAR then inactivates Rap. The RhoA pathway is shown in light blue: Upon ephrin-A treatment, EphA recruits and phosphorylates Cdk5, which in turn phosphorylates and activates a RhoGEF, ephexin, activating RhoA. RhoA then activates ROCK, leading to dendritic spine retraction (as shown by the dashed pink box). The dashed blue box indicates the part of this pathway that has been shown to be important for growth cone collapse. The Rac pathway is shown in green: Activation of EphA receptors leads to binding and phosphorylation of the RacGAP α2-chimaerin, which then inactivaes Rac1 in cortical neurons, leading to growth cone collapse. In retinal axons, ephrin binding to EphA receptors leads to activation of the Rho family GEF Vav2, which then activates Rac1. Vav2-mediated activation of Rac1 leads to endocytosis of the membrane, eventually leading to growth cone collapse. In reverse signaling, ephrin-A associates with the p75-NTR receptor. This complex works to phosphorylate Fyn and cause axon repulsion from EphA-expressing cells when EphA binds ephrin-A. B: ephrin–A-EphA signaling in the vascular system. There is limited information on how this signaling regulates angiogenesis, but ephrin-A expression is known to be regulated by HIF-2α expression in surrounding tissue and signaling through EphA in the vascular system can lead to angiogenesis in tumor models. C: ephrin–B-EphB signaling in the nervous system. EphB is recruited to the membrane by GRIP1, a multi-PDZ domain scaffolding protein. The Rac1 pathway is shown in green: Rac1 is activated by the GEFs Kalirin and Tiam1. Both Tiam1 and Kalirin bind to and are phosphorylated by the activated receptor and then activate Rac1, leading to increased dendrite morphogenesis. The RhoA pathway is shown in blue: EphA activation leads to phosphorylation of FAK, which then activates RhoA, activating ROCK and leading to increased dendrite morphogenesis. For reverse signaling through the ephrin-B ligand, several adaptor proteins are required. GRIP1 binds to ephrin-B3 and is perhaps involved in clustering it at the synapse. The SH2-SH3 domain containing adaptor protein Grb4 binds ephrin-Bs and links them with multiple downstream regulators and enhancing dendrite morphogenesis in the ligand-expressing cell. D: ephrin-B–EphB signaling in the vascular system. EphB activation leads to the activation of RhoA and ROCK. In addition, EphB signaling enhances SFD/CXCR4 signaling as seen by increased phosphorylation of Akt. Both pathways lead to endothelial cell migration and sprouting. For reverse signaling, ephrin-B binds the SH2-SH3 domain containing adaptor protein Grb4, leading to vessel sprouting, presumably through multiple downstream regulators recruited by Grb4.

Regarding the pathway regulated by R-Ras, Sema3A uses the same Rnd1-R-Ras activation mechanism and downstream PI3K-Akt—GSK3β-CRMP2 pathway as Sema4D [21]. In addition, Sema3A-induced inactivation of PI3K can also trigger two other cytoskeletal changes that contribute to growth cone collapse. First, Sema3A-induced signal inhibits ERM phosphorylation in growth cone filopodia and causes growth cone collapse [22]. Secondly, Sema3A-induced signal activates myosinII through the PI3K-Akt pathway. Activated myosinII then associates with actin to generate cellular contractile forces in DRG neurons, contributing to growth cone collapse [23]. In addition, a recent report suggests that PTEN, an antagonist of PI3K, induces GSK3β activation in DRG neurons upon Sema3A treatment, probably through the suppression of PI3K activity [24] (Figure 2A).

In addition to the aforementioned small GTPases, several kinases have also been shown to play important roles in Sema3A signaling. The first is PIPKIγ661, which is inhibited by the FARP2 released from PlexinA1, suppresses integrin induced adhesion in the leading edge of growth cone [20]. Secondly, Fyn, which is activated by associating with PlexinA1, activates another kinase, Cdk5, which then phosphorylates CRMP2 [25, 26]. Finally, Fer and Fes, which binds PlexinA1 and directly phosphorylate CRMP2 after Sema3A treatment [27, 28] (Figure 2A). For information about additional Sema3A signaling pathways in neurons, see the review by Tran and colleagues [7].

In vitro treatment of endothelial cells with Sema3A inhibits their migration, vessel formation, and promotes permeability [29–33]. Whether Sema3A–Npn-1/PlexA signaling mediates these effects in endothelial cells in vivo is unclear, even though endothelial cells express Npn-1 and plexin receptors [34]. One complication of studying this signaling event in endothelial cells is that Npn-1 is also a receptor for VEGF, a protein that is critically important for endothelial cell development and function [35]. In zebrafish, either overexpression or a deficiency of Sema3A orthologs lead to vessel-patterning defects [32], suggesting that Sema3A is essential for vascular development, although the penetrance of these defects is low. However, no detectable vascular defect was found in either Sema3A knockout mice or Npn-1Sema- mice lacking Sema3A–Npn-1 signaling. This suggests that Sema3A–Npn-1 signaling is not essential for general vascular development in mice [36, 37], but it would be interesting to test whether Sema3A signaling functions in pathological processes.

In endothelial cells, three possible mechanisms for Sema3A signaling have been proposed based on in vitro studies (Figure 1D). First, Sema3A, by an unknown mechanism, changes integrin affinity for the ECM, which inhibits integrin-mediated adhesion of endothelial cells to the ECM and allow for the de-adhesion necessary for vascular remodeling [31]. Secondly, Sema3A, through unknown mechanisms, blocks VEGF-induced FAK and Src phosphorylation and consequently disrupts VEGF-mediated angiogenesis [29]. Although some have suggested that Sema3A affects VEGF-induced angiogenesis by competing with VEGF for Npn-1 [30], more evidence has shown that Sema3A and VEGF use different, non-overlapping sites on Npn-1 for binding, making competitive binding unlikely [38, 39]. Finally, Sema3A induces tyrosine phosphorylation of VE-cadherin through the PI3K-Akt pathway, thus promoting vascular permeability [29]. How Sema3A is linked to the PI3K-Akt pathway in the vascular system is not yet clear, and it would be interesting to see whether the molecules involved in Sema3A-induced PI3K-Akt signaling in the nervous system also participate in endothelial cells. It is important to point out that if indeed there is Npn-1 mediated Sema3A signaling in endothelial cells, it is not clear whether PlexinA receptors or VEGFR2 are its co-receptors. Recent evidence suggests that another plexin, Plexin-D1, might be the co-receptor of Npn-1 for Sema3A signaling. Studies in zebrafish show that knockdown of Sema3a1, Sema3a2, and Plexin-D1 lead to vessel patterning defects, presumably through a Npn-1–PlexinD1 complex [33]. However, in mice, another class 3 semaphorin, Sema3E, not Sema3A, binds and signals through Plexin-D1 directly and independently of Npn-1 to pattern developing blood vessels [40].

The recent discovery of Sema3E and its receptor Plexin-D1 might serve as a better example to demonstrate the dual function of class 3 semaphorins in neurons and endothelial cells. Both in vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that Sema3E exerts a repulsive effect through Plexin-D1 in the vascular and nervous systems [40, 41] and the presence of Npn-1 converts this repulsive effect into attraction in neurons [41]. Identification of their downstream signaling pathways in both neurons and endothelial cells will provide further insight into the similarities and differences of class 3 semaphorin signaling in neurons and endothelial cells.

In summary, semaphorins have been studied as key guidance cues regulating neural and vascular development via similar and distinct signaling mechanisms. Although there are many different regulators in the two systems, partly due to the difference in cell type, semaphorin signaling uses similar principles. For example, in both systems, Sema4D uses the same small GTPases (for example RhoA) as its main mode of action, but is also is able to either use the same (PDZGEF and LARG) or different (ErbB2 or Met) regulators to activate the network. Another example is the PI3K-Akt pathway, which is used in both Sema3A and Sema4D signaling cascades and is shared in the nervous and vascular systems. Moreover, further investigation of the signaling pathways of other semaphorin family members that also play guidance functions in both neurons and endothelial cells, including Sema3C, 3F, Sema5A/5B and Sema6A [7, 42, 43], will shed new light on the mechanistic similarities between both systems. Finally, it is worth pointing out that most of the mechanistic work described in this section has been performed in vitro, so in vivo validation of these signaling molecules and how they function together will be required.

Ephrins

Ephrin ligands and their Eph receptors play important roles in neural and vascular development [44]. There are two families of ephrins—the ephrin-A and ephrin-B family. Ephrin-A ligands are GPI-anchored to the membrane and bind to EphA receptors, while ephrin-B ligands are transmembrane proteins that bind to EphB receptors (Box 2).

Ephrin-A–EphA signaling in the nervous and vascular systems

Ephrin-A signaling has been studied more extensively in the neuronal system than in the vascular system. Ephrin-A–EphA signaling leads to axon growth cone collapse and dendrite retraction (Figure 2A). EphAs play important role in establishing axon topographic maps especially from the retina to the superior colliculus and EphA7 knockout mice exhibit an aberrant innervation pattern in the superior colliculus [45]. EphA–ephrin-A signaling has not been extensively studied in the developing vasculature, but rather in pathological contexts. Ephrin-A1 and EphA2 are expressed in tumor neovasculature as well as in HUVECs. Treatment of HUVECs expressing a dominant-negative EphA2 with ephrin-A1 inhibits capillary tube-like formation [46]. Ephrin-A1 expression in tumor vasculature is regulated by hypoxia-inducible response factor-2α in the surrounding tissue, and blocking ephrin-A1 with an inhibitor can impair angiogenesis [47] (Figure 2B).

Small GTPases play a critical role in ephrin-A signaling (Figure 2A). Firstly, in hippocampal axons, EphAs have been shown to interact with the spine-associated RapGAP (SPAR), leading to the inactivation of the small GTPase Rap1 and causing growth cone collapse [48]. Secondly, Rac1 regulation of filopodial dynamics and membrane internalization is involved in EphA-mediated growth cone collapse. Both the activation and inactivation of Rac1 can cause growth cone collapse, and whether these events both occur in the same cell using the same players is unclear. In cortical neurons, Rac1 is inactivated by the RacGAP α2-Chimaerin, which interacts with EphA4 and leads to actin depolymerization followed by growth cone collapse. Blocking α2-Chimaerin prevents growth cone collapse in vitro and, importantly, α2-Chimaerin knockout mice phenocopy the EphA4 knockout neuronal phenotype of abnormal corticospinal and spinal interneuron circuitry, ultimately leading to a hopping gait [49–51]. In retinal ganglion cells, Rac1 is activated by the Vav family of GEFs, leading to internalization of the membrane, reorganization of F-actin, and growth cone collapse [52]. Thirdly, RhoA activity is involved in ephrin-A–EphA triggered growth cone collapse. The activation of EphA receptors leads to the activation of of ephexin, a RhoGEF that activates RhoA, leading to ROCK activation and growth cone collapse via depolymerization of F-actin and inhibition of F-actin turnover [53]. In hippocampal neurons, EphA4 activation leads to Cdk5 phosphorylation, which then phosphorylates ephexin, leading to RhoA activation and dendritic spine retraction [54]. EphA4 regulates spine morphogenesis via activation of PLCγ, leading to activation of Cofilin, actin fiber destabilization, and resulting dendritic spine retraction [55]. Whether these same small GTPases play a role in ephrin-A–EphA signaling in endothelial cells is unknown.

Even though ephrin-A ligands are not transmembrane proteins, they do engage in reverse signaling (Figure 2A). A recent study has shown that in retinal axons, ephrin-A forms a complex with the p75 neurotrophin receptor (NTR), causing Fyn phosphorylation upon activation of EphA receptors and leading to axon repulsion from inappropriate targets [56]. Retinal-specific p75(NTR) knockout mice have defects in retinal axon target innervation in the brain. Whether or not this is a mechanism employed by endothelial cells is still an open question.

Ephrin-B–EphB signaling in the nervous and vascular systems

In neurons, ephrin-Bs regulate both axon guidance and dendritic spine morphogenesis (Box 2). Dendritic spines are post-synaptic structures that are primarily composed of actin and are capable of changing their shape in a very short time scale (Box 1) [57]. Hippocampal neurons express ephrin-B ligands both pre- and postsynaptically and EphB receptors postsynaptically [58]. Treatment of hippocampal neurons with exogenous ephrin-B or EphB receptor leads to increased spine morphogenesis and EphB1/B2/B3 triple knockout mice have reduced dendritic spine density [59]. Ephrin-B–EphB signaling has also been shown to play a role in the repulsive axon guidance of several neuronal populations, see review [60].

In the vascular system, ephrin-B2 is expressed in the arteries, whereas EphB4 is expressed in the veins, and this division allows for demarcation of the vessel types. Ephrin-B2 and EphB2/B3 null mice die early in development with disorganized vasculature. Animals lacking the cytoplasmic domain of ephrin-B2 phenocopy the ephrin-B2 nulls, indicating that reverse signaling through the ephrin ligand is also important for vascular development. In addition, just as treatment of neurons with exogenous ephrin-B2 leads to excess dendritic spine formation, treatment with ephrin-B1 causes excess capillary sprouting in vitro [61].

Forward signaling through Eph receptors is used in both neurons and endothelial cells, and common players such as the small GTPase RhoA play an important role in both systems. In neurons, after receptor phosphorylation upon ligand binding, EphB2 is targeted and maintained at the post-synaptic membrane via the multi-PDZ domain scaffold protein GRIP1, which binds many post-synaptic proteins [59]. Ephrin-B1 activation of EphB2 leads to several events which ultimately affect RhoA or Rac1: First, the Rac1GEF Tiam1 (Table 1) is phosphorylated and interacts with EphB2, leading to cytoskeletal rearrangement and increased spine formation in vitro. Eliminating Tiam1 from neurons using RNAi silencing leads to a dearth of spines [62]. Secondly, the RhoGEF Kalirin is activated and translocates to the dendrite, leading to the activation of Rac1 and PAK, thus increasing spine morphogenesis [63]. Thirdly, focal adhesion kinase (FAK) is phosphorylated upon ligand binding and activates RhoA and consequently knock-out of either of these genes in cultured neurons blocked ephrin–induced increases in dendrite number (Figure 2C) [64]. Similarly, in endothelial cells, RhoA is also activated following EphB activation. Ephrin-B treatment of HUVECs (human umbilical vein endothelial cells) leads to cell retraction, and this effect can be partially blocked by the application of RhoA/ROCK inhibitors [65] (Figure 2D).

Reverse signaling through ephrin-B ligands is also involved in neural and vascular development. For example, common adaptor proteins are recruited to the ephrin-B complex in both neurons and endothelial cells (Figures 2C and D). In neurons, the scaffolding protein GRIP1 interacts with postsynaptic ephrin-B3 and regulates synapse number in the postsynaptic membrane [66]. In addition, Grb4, a SH2 and SH3 domain containing adaptor protein is localized in hippocampal dendrites and mediates ephrin-mediated dendrite morphogenesis [67] by linking ephrin-B to downstream effectors including Abi-1, Pak1, Cbl-associated protein (CAP), and Dynamin [68]. Similarly, in endothelial cells, Grb4 is also recruited to the ephrin-B–EphB complex following EphB activation and causes vessel sprouting [69]. For additional information about ephrin-B reverse signaling, see review [70].

Ephrin-B signaling in endothelial cells is also mediated by molecules not found to be involved in the nervous system. EphBs can cross-talk with other ligand-receptor pairs. For example, ephrin-B1 and –B2 activate human endothelial cells that express EphB2 and B4, enhancing the effects of the ligand–receptor pair SDF-1–CXCR4 as seen by enhanced Akt phosphorylation during in vitro endothelial cell assembly into capillary-like structures (Figure 2D) [71].

In summary, ephrin-A and –B signaling is important for both neuronal and vascular development and some common themes emerge. First, both in the vascular and nervous systems, ephrins–Ephs are trafficked and carefully regulated at the membrane by scaffolding proteins such as Grb4. In the nervous system, Ephs are also precisely compartmentalized within the cell, with EphBs primarily found in dendrites, and EphAs mostly localized in axons. Although endothelial cells in the vasculature lack this complex cytoarchitecture, it would be interesting to see whether Ephs are differentially localized in endothelial cells with differing functions, such as tip or stalk cells, or whether different Eph receptors are localized at the leading or trailing end of the migrating cell. Secondly, processes in both systems, including dendritic spine formation, endothelial cell migration, and angiogenesis, use both forward and reverse signaling to regulate cytoskeletal dynamics via small GTPases (RhoA). However, there are still some challenges in the field. Unlike the semaphorin family, ephrins are very promiscuous in their binding, with most A-family ligands binding most EphA receptors, and most B-family ligands binding most EphB receptors. Knocking down ephrins or Ephs in vivo can often lead to compensation by other family members, making the identification of their exact signaling and function difficult. Additionally, while some of the signaling molecules downstream of these proteins have been identified and even confirmed in vivo, how these molecules are linked together to form a coherent picture to mediate ephrin– Eph effects is not known. As more molecules involved in the vascular signaling of ephrins and Ephs are identified, the similarities or differences between the two systems will become more apparent.

VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a key regulator of angiogenesis (Box 2). VEGF mediates vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and vascular permeability by affecting cellular processes such as proliferation and cell migration. Recently, VEGF was also shown to play an autocrine role in the maintenance of adult vasculature, as mice lacking VEGF in adult vasculature undergo progressive endothelial degeneration eventually leading to death [72]. VEGF and its receptors are also expressed in neurons and glia, and preliminary reports have indicated that they play a role in the maintenance of neural precursor identity and proliferation, neuroprotection, adult neurogenesis, and neuronal migration [73].

VEGF-A signaling in the vascular and nervous systems

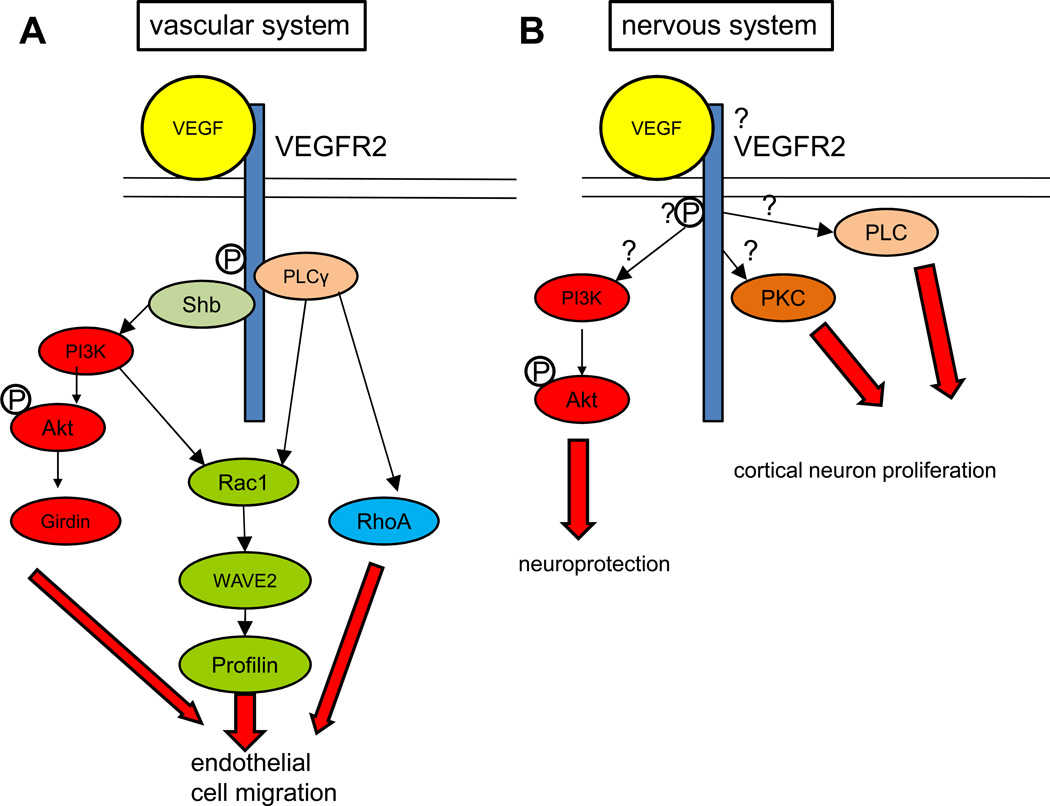

In endothelial cells, VEGF induces VEGR2 phosphorylation via several sites. Tyr 1175 is critical for proper vascular development, as knock-in mice with an amino acid substitution at Tyr 1175 (Tyr→Phe) lack Tyr 1175 autophosphorylation and phenocopy VEGFR2 knockout mice, which die early in development with impaired vasculogenesis [74]. Phosphorylation of VEGFR2 at Tyr1175 leads to binding of adaptor proteins such as Shb and subsequently activates PI3K. PI3K activates Akt, which mediates endothelial cell migration through substrates such as Girdin, an actin binding protein [75] (Figure 3A). PI3K also leads to the activation of the small GTPase Rac1. Rac1 stimulates membrane ruffling, or the formation of new actin-rich cell protrusions, by associating with WAVE2, which regulates profilin, an actin binding protein involved in the polymerization of actin filaments. In addition, VEGFR2 can directly activate PLCγ. PLC activates the small GTPases Rac1 and RhoA to induce endothelial cell migration [76]. For more discussion of VEGF signaling, see Box 2 and review [77].

Figure 3. VEGF-VEGFR2 signaling in the nervous and vascular systems.

A: VEGF signaling in the vascular system: The PI3K-Akt pathway is shown in red: VEGF binding to VEGFR2 causes autophosphorylation of the receptor. Phosphorylation of the receptor at tyrosine 1175 causes the recruitment of the adaptor protein Shb, which then activates PI3K. PI3K phosphorylates Akt, which acts through substrates like the actin binding protein Girdin to regulate endothelial cell migration. The Rac1 pathway is shown in green: PI3K also activates Rac1, which regulates migration through the effectors WAVE2 and the actin binding protein Profilin. Phosphorylation of Tyr1175 also causes activation of PLCγ, which activates the small GTPases Rac1 and RhoA to regulate endothelial cell migration. B: VEGF-VEGFR2 signaling in the nervous system: Many of the same proteins used by VEGFR2 signaling in the vascular system are also implicated to act in the nervous system, but the evidence for this is less clear (indicated by question marks). PI3K inhibitors abrogate VEGFs neuroprotective effect, while PLC and PKC inhibitors prevented the neurotrophic effect exerted by VEGF on cortical neurons.

Similarly, the PI3K-Akt pathway is also involved in VEGFR2 signaling in neurons. VEGF treatment of several neuronal types leads to neuroprotection against injury. Spinal cord motorneurons of SOD mice, a genetic model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), are protected from degeneration by exogenous treatment with VEGF [78] and PI3K inhibitors prevent this protective effect [79]. However, whether this protective effect affects neurons directly or indirectly is still unknown. Axotimized retinal ganglion cells have also been found to be protected from degeneration by treatment with VEGF, and show increased levels of phosphorylated Akt after VEGF treatment. The neuroprotective effect exerted by VEGF on retinal neurons is blocked by Akt inhibitors [80]. In vitro studies have also indicated that VEGF signaling involves PI3K, PLC, and PKC to mediate cortical neuron proliferation [81] (Figure 3B), but whether these pathways are also involved in processes like VEGF-mediated neuronal migration is not known.

The role of the VEGFR2 co-receptor Npn-1 in VEGF signaling is starting to be uncovered. As mentioned previously, Npn-1 binds both VEGF and Semaphorin3A. In vivo studies show that an endothelial-specific Npn-1 knockout mouse has severe vascular defects. However, a Npn-1Sema- knock-in mouse that has no Npn-1–Sema3 binding has none of these defects, indicating that Sema3-Npn1 interaction is not necessary for vascular development [36]. This suggests that the VEGF-Npn-1 interaction plays a vital role in vascular development. Several lines of evidence point to the fact that Npn-1 can enhance VEGF–VEGFR2 mediated vascular function. VEGFR2 and Npn-1 complex formation is induced by by VEGF binding and they are internalized together via a clathrin-dependent mechanism [82]. VEGF has a greater anti-apoptotic effect on Npn-1/VEGFR2 expressing cells than on cells expressing only VEGFR2 [83]. In addition, injection of function-blocking antibodies against Npn-1 and VEGF into the postnatal retina inhibited angiogenesis more severely than that of an anti-VEGF antibody alone. The same effect is seen with antibody injection in a tumor angiogenesis model [84]. Npn-1 has also been shown to enhance VEGFR2 induces p38MAPK activation [85].

Recent studies suggest that Npn-1 can also signal independently of VEGFR2. When the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of Npn-1 were fused to the extracellular portion of the EGF receptor and transfected into HUVECs, EGF treatment could still induce cell migration in the presence of VEGFR2 function-blocking antibodies [86]. Conversely, function-blocking antibodies against Npn-1 block VEGF121 mediated endothelial cell migration despite the fact that VEGF121 is unable to promote Npn-1 and VEGFR2 complex formation [39]. To definitively identify the role of VEGF–Npn-1 function in both the nervous and vascular systems, a mouse model that selectively eliminates VEGF binding to Npn-1 in a temporally and spatially controlled manner is needed.

In summary, more is known about VEGF-A signaling in the vascular than nervous system. However, these studies have mostly been performed in vitro using biochemical approaches or by antibody injection in animals. Mouse models are required in order to fully parse the in vivo roles of individual signaling molecules in each process. Due to the importance of many of these signaling components to the survival of the organism, mouse models must both be temporally and spatially tractable. Moreover, as some of the signaling pathways used in the vascular system have begun to be implicated in the neuronal system, future studies will focus on their in vivo significance. It will also be important to begin to address the VEGF signaling pathways involved in neuronal migration and neurogenesis. Finally, there is no doubt that knowledge about VEGF signaling in the vascular system could guide future studies on its signaling in the nervous system.

Concluding remarks

Both the nervous and vascular systems are dynamic, highly adaptable organ systems whose development is controlled using a multitude of cues, including the proteins covered here, as well as molecules such as Netrins and Slits. Similarities exist between the signaling mechanisms used in the nervous and vascular systems on several levels. First, the working principles used in both systems are similar. For example, the activation of each receptor leads to the re-arrangement of the cytoskeleton through small GTPases, whether for the purpose of growth cone guidance, dendrite formation, or vascular tip cell guidance. Secondly, some common receptors are used by different ligands to regulate both neuronal and vascular development. For example, Npn-1 is a receptor both for semaphorins and VEGF, and VEGFR2 is a receptor for Sema6D in addition to VEGF [87]. Thirdly, there is cross-talk between the downstream signaling molecules from different ligand-receptor pairs. For example, Sema3A influences VEGF function by blocking some of its downstream signaling molecules [29]. An interesting question for the future is how growth cones or endothelial cells integrate multiple signals to control cell behavior when they encounter multiple environmental cues. Moreover, whether ligands and receptors expressed in nerves interact with their counterparts on vessels, and vice versa, and how their signaling contributes to vessel-nerve interaction is an exciting question for the future. Future studies on this topic can focus on identifying more players, not only the signals that directly lead to cytoskeletal changes, but also signals regulating receptor expression and trafficking, generating a better picture of the relationships between all of the involved players, and a more thorough understanding of the in vivo roles of each of the proteins involved in this process. Furthermore, identification of molecules involved downstream of Ephrins, Semaphorins, and VEGF can provide novel therapeutic targets for both vascular and neurological diseases. Since some of the same molecules are used in both systems, drugs currently used in one system could potentially be applicable to disorders of the other system.

Acknowledgements

We apologize to all of the authors whose work has been omitted from this review because of space limitations. We would like to thank the Gu lab for their insightful discussions. In addition, we would like to thank Alex Kolodkin, Jeroen Pasterkamp, Vladimir Gelfand, Arie Horowitz, Seth Margolis, Anna Serpinskaya, and Christiana Ruhrberg for reading this review and offering helpful suggestions. Work in the authors’ laboratory was supported by grants from the Basil O’Connor Starter Scholar Research Award from the March of Dimes Foundation, Klingenstein Fellowship Award in the Neurosciences, Whitehall Foundation Award, Sloan Research Fellowship to C.G. M.V.G is a Stuart H.Q. and Victoria Quan Fellow at Harvard Medical School.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carmeliet P, Tessier-Lavigne M. Common mechanisms of nerve and blood vessel wiring. Nature. 2005;436(7048):193–200. doi: 10.1038/nature03875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerhardt H, et al. VEGF guides angiogenic sprouting utilizing endothelial tip cell filopodia. J Cell Biol. 2003;161(6):1163–1177. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freitas C, Larrivee B, Eichmann A. Netrins and UNC5 receptors in angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2008;11(1):23–29. doi: 10.1007/s10456-008-9096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Legg JA, et al. Slits and Roundabouts in cancer, tumour angiogenesis and endothelial cell migration. Angiogenesis. 2008;11(1):13–21. doi: 10.1007/s10456-008-9100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones CA, Li DY. Common cues regulate neural and vascular patterning. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2007;17(4):332–336. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Suchting S, Bicknell R, Eichmann A. Neuronal clues to vascular guidance. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312(5):668–675. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tran TS, Kolodkin AL, Bharadwaj R. Semaphorin regulation of cellular morphology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:263–292. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010605.093554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oinuma I, et al. The Semaphorin 4D receptor Plexin-B1 is a GTPase activating protein for R-Ras. Science. 2004;305(5685):862–865. doi: 10.1126/science.1097545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oinuma I, Katoh H, Negishi M. Molecular dissection of the semaphorin 4D receptor plexin-B1-stimulated R-Ras GTPase-activating protein activity and neurite remodeling in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24(50):11473–11480. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3257-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ito Y, et al. Sema4D/plexin-B1 activates GSK-3beta through R-Ras GAP activity, inducing growth cone collapse. EMBO Rep. 2006;7(7):704–709. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fazzari P, et al. Plexin-B1 plays a redundant role during mouse development and in tumour angiogenesis. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:55. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basile JR, et al. Class IV semaphorins promote angiogenesis by stimulating Rho-initiated pathways through plexin-B. Cancer Res. 2004;64(15):5212–5224. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basile JR, et al. Semaphorin 4D provides a link between axon guidance processes and tumor-induced angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(24):9017–9022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508825103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sierra JR, et al. Tumor angiogenesis and progression are enhanced by Sema4D produced by tumor-associated macrophages. J Exp Med. 2008;205(7):1673–1685. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swiercz JM, Kuner R, Offermanns S. Plexin-B1/RhoGEF-mediated RhoA activation involves the receptor tyrosine kinase ErbB-2. J Cell Biol. 2004;165(6):869–880. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Basile JR, Gavard J, Gutkind JS. Plexin-B1 utilizes RhoA and Rho kinase to promote the integrin-dependent activation of Akt and ERK and endothelial cell motility. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(48):34888–34895. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705467200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fukata Y, et al. CRMP-2 binds to tubulin heterodimers to promote microtubule assembly. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4(8):583–591. doi: 10.1038/ncb825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vikis HG, et al. The semaphorin receptor plexin-B1 specifically interacts with active Rac in a ligand-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(23):12457–12462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.220421797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vikis HG, Li W, Guan KL. The plexin-B1/Rac interaction inhibits PAK activation and enhances Sema4D ligand binding. Genes Dev. 2002;16(7):836–845. doi: 10.1101/gad.966402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toyofuku T, et al. FARP2 triggers signals for Sema3A-mediated axonal repulsion. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(12):1712–1719. doi: 10.1038/nn1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eickholt BJ, Walsh FS, Doherty P. An inactive pool of GSK-3 at the leading edge of growth cones is implicated in Semaphorin 3A signaling. J Cell Biol. 2002;157(2):211–217. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200201098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallo G. Semaphorin 3A inhibits ERM protein phosphorylation in growth cone filopodia through inactivation of PI3K. Dev Neurobiol. 2008;68(7):926–933. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orlova I, Silver L, Gallo G. Regulation of actomyosin contractility by PI3K in sensory axons. Dev Neurobiol. 2007;67(14):1843–1851. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chadborn NH, et al. PTEN couples Sema3A signalling to growth cone collapse. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 5):951–957. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sasaki Y, et al. Fyn and Cdk5 mediate semaphorin-3A signaling, which is involved in regulation of dendrite orientation in cerebral cortex. Neuron. 2002;35(5):907–920. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00857-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uchida Y, et al. Semaphorin3A signalling is mediated via sequential Cdk5 and GSK3beta phosphorylation of CRMP2: implication of common phosphorylating mechanism underlying axon guidance and Alzheimer's disease. Genes Cells. 2005;10(2):165–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2005.00827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mitsui N, et al. Involvement of Fes/Fps tyrosine kinase in semaphorin3A signaling. EMBO J. 2002;21(13):3274–3285. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shapovalova Z, Tabunshchyk K, Greer PA. The Fer tyrosine kinase regulates an axon retraction response to Semaphorin 3A in dorsal root ganglion neurons. BMC Dev Biol. 2007;7:133. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Acevedo LM, et al. Semaphorin 3A suppresses VEGF-mediated angiogenesis yet acts as a vascular permeability factor. Blood. 2008;111(5):2674–2680. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-110205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miao HQ, et al. Neuropilin-1 mediates collapsin-1/semaphorin III inhibition of endothelial cell motility: functional competition of collapsin-1 and vascular endothelial growth factor-165. J Cell Biol. 1999;146(1):233–242. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.1.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Serini G, et al. Class 3 semaphorins control vascular morphogenesis by inhibiting integrin function. Nature. 2003;424(6947):391–397. doi: 10.1038/nature01784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shoji W, et al. Semaphorin3a1 regulates angioblast migration and vascular development in zebrafish embryos. Development. 2003;130(14):3227–3236. doi: 10.1242/dev.00516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Torres-Vazquez J, et al. Semaphorin-plexin signaling guides patterning of the developing vasculature. Dev Cell. 2004;7(1):117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herzog Y, Guttmann-Raviv N, Neufeld G. Segregation of arterial and venous markers in subpopulations of blood islands before vessel formation. Dev Dyn. 2005;232(4):1047–1055. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soker S, et al. Neuropilin-1 is expressed by endothelial and tumor cells as an isoform-specific receptor for vascular endothelial growth factor. Cell. 1998;92(6):735–745. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81402-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gu C, et al. Neuropilin-1 conveys semaphorin and VEGF signaling during neural and cardiovascular development. Dev Cell. 2003;5(1):45–57. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00169-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vieira JM, Schwarz Q, Ruhrberg C. Selective requirements for NRP1 ligands during neurovascular patterning. Development. 2007;134(10):1833–1843. doi: 10.1242/dev.002402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Appleton BA, et al. Structural studies of neuropilin/antibody complexes provide insights into semaphorin and VEGF binding. EMBO J. 2007;26(23):4902–4912. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pan Q, et al. Neuropilin-1 binds to VEGF121 and regulates endothelial cell migration and sprouting. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(33):24049–24056. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gu C, et al. Semaphorin 3E and plexin-D1 control vascular pattern independently of neuropilins. Science. 2005;307(5707):265–268. doi: 10.1126/science.1105416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chauvet S, et al. Gating of Sema3E/PlexinD1 signaling by neuropilin-1 switches axonal repulsion to attraction during brain development. Neuron. 2007;56(5):807–822. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bielenberg DR, Klagsbrun M. Targeting endothelial and tumor cells with semaphorins. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2007;26(3–4):421–431. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9097-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neufeld G, Kessler O. The semaphorins: versatile regulators of tumour progression and tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8(8):632–645. doi: 10.1038/nrc2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Himanen JP, Saha N, Nikolov DB. Cell-cell signaling via Eph receptors and ephrins. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19(5):534–542. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rashid T, et al. Opposing gradients of ephrin-As and EphA7 in the superior colliculus are essential for topographic mapping in the mammalian visual system. Neuron. 2005;47(1):57–69. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ogawa K, et al. The ephrin-A1 ligand and its receptor, EphA2, are expressed during tumor neovascularization. Oncogene. 2000;19(52):6043–6052. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamashita T, et al. Hypoxia-inducible transcription factor-2alpha in endothelial cells regulates tumor neovascularization through activation of ephrin A1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(27):18926–18936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709133200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Richter M, et al. The EphA4 receptor regulates neuronal morphology through SPAR-mediated inactivation of Rap GTPases. J Neurosci. 2007;27(51):14205–14215. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2746-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beg AA, et al. alpha2-Chimaerin is an essential EphA4 effector in the assembly of neuronal locomotor circuits. Neuron. 2007;55(5):768–778. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wegmeyer H, et al. EphA4-dependent axon guidance is mediated by the RacGAP alpha2-chimaerin. Neuron. 2007;55(5):756–767. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Iwasato T, et al. Rac-GAP alpha-chimerin regulates motor-circuit formation as a key mediator of EphrinB3/EphA4 forward signaling. Cell. 2007;130(4):742–753. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cowan CW, et al. Vav family GEFs link activated Ephs to endocytosis and axon guidance. Neuron. 2005;46(2):205–217. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shamah SM, et al. EphA receptors regulate growth cone dynamics through the novel guanine nucleotide exchange factor ephexin. Cell. 2001;105(2):233–244. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00314-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fu WY, et al. Cdk5 regulates EphA4-mediated dendritic spine retraction through an ephexin1-dependent mechanism. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(1):67–76. doi: 10.1038/nn1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou L, et al. EphA4 signaling regulates phospholipase Cgamma1 activation cofilin membrane association, and dendritic spine morphology. J Neurosci. 2007;27(19):5127–5138. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1170-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lim YS, et al. p75(NTR) Mediates Ephrin-A Reverse Signaling Required for Axon Repulsion and Mapping. Neuron. 2008;59(5):746–758. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schubert V, Dotti CG. Transmitting on actin: synaptic control of dendritic architecture. J Cell Sci. 2007;120(Pt 2):205–212. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takasu MA, et al. Modulation of NMDA receptor-dependent calcium influx and gene expression through EphB receptors. Science. 2002;295(5554):491–495. doi: 10.1126/science.1065983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hoogenraad CC, et al. GRIP1 controls dendrite morphogenesis by regulating EphB receptor trafficking. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(7):906–915. doi: 10.1038/nn1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reber M, Hindges R, Lemke G. Eph receptors and ephrin ligands in axon guidance. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2007;621:32–49. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-76715-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lamont RE, Childs S. MAPping out arteries and veins. Sci STKE. 2006;2006(355):e39. doi: 10.1126/stke.3552006pe39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tolias KF, et al. The Rac1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor Tiam1 mediates EphB receptor-dependent dendritic spine development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(17):7265–7270. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702044104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Penzes P, et al. Rapid induction of dendritic spine morphogenesis by trans-synaptic ephrinB-EphB receptor activation of the Rho-GEF kalirin. Neuron. 2003;37(2):263–274. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Moeller ML, et al. EphB receptors regulate dendritic spine morphogenesis through the recruitment/phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase and RhoA activation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(3):1587–1598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511756200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Groeger G, Nobes CD. Co-operative Cdc42 and Rho signalling mediates ephrinB-triggered endothelial cell retraction. Biochem J. 2007;404(1):23–29. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aoto J, et al. Postsynaptic ephrinB3 promotes shaft glutamatergic synapse formation. J Neurosci. 2007;27(28):7508–7519. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0705-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Segura I, et al. Grb4 and GIT1 transduce ephrinB reverse signals modulating spine morphogenesis and synapse formation. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10(3):301–310. doi: 10.1038/nn1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cowan CA, Henkemeyer M. The SH2/SH3 adaptor Grb4 transduces B-ephrin reverse signals. Nature. 2001;413(6852):174–179. doi: 10.1038/35093123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Georgakopoulos A, et al. Metalloproteinase/Presenilin1 processing of ephrinB regulates EphB-induced Src phosphorylation and signaling. EMBO J. 2006;25(6):1242–1252. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cowan CA, Henkemeyer M. Ephrins in reverse, park and drive. Trends Cell Biol. 2002;12(7):339–346. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)02317-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Salvucci O, et al. EphB2 and EphB4 receptors forward signaling promotes SDF-1-induced endothelial cell chemotaxis and branching remodeling. Blood. 2006;108(9):2914–2922. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-023341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lee S, et al. Autocrine VEGF signaling is required for vascular homeostasis. Cell. 2007;130(4):691–703. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rosenstein JM. VEGF in the Nervous System. In: Ruhrberg C, editor. VEGF in Development. Austin, TX: Landes Bioscience; 2008. p. 118. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sakurai Y, et al. Essential role of Flk-1 (VEGF receptor 2) tyrosine residue 1173 in vasculogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(4):1076–1081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404984102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kitamura T, et al. Regulation of VEGF-mediated angiogenesis by the Akt/PKB substrate Girdin. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(3):329–337. doi: 10.1038/ncb1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Taylor CJ, Motamed K, Lilly B. Protein kinase C and downstream signaling pathways in a three-dimensional model of phorbol ester-induced angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2006;9(2):39–51. doi: 10.1007/s10456-006-9028-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Olsson AK, et al. VEGF receptor signalling - in control of vascular function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(5):359–371. doi: 10.1038/nrm1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Storkebaum E, et al. Treatment of motoneuron degeneration by intracerebroventricular delivery of VEGF in a rat model of ALS. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(1):85–92. doi: 10.1038/nn1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tolosa L, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor protects spinal cord motoneurons against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Neurochem. 2008;105(4):1080–1090. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kilic U, et al. Human vascular endothelial growth factor protects axotomized retinal ganglion cells in vivo by activating ERK-1/2 and Akt pathways. J Neurosci. 2006;26(48):12439–12446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0434-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhu Y, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor promotes proliferation of cortical neuron precursors by regulating E2F expression. FASEB J. 2003;17(2):186–193. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0515com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Salikhova A, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and semaphorin induce neuropilin-1 endocytosis via separate pathways. Circ Res. 2008;103(6):e71–e79. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.183327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang L, et al. Neuropilin-1 modulates p53/caspases axis to promote endothelial cell survival. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(11):e1161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pan Q, et al. Blocking neuropilin-1 function has an additive effect with anti-VEGF to inhibit tumor growth. Cancer Cell. 2007;11(1):53–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Kawamura H, et al. Neuropilin-1 in regulation of VEGF-induced activation of p38MAPK and endothelial cell organization. Blood. 2008;112(9):3638–3649. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-125856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang L, et al. Neuropilin-1-mediated vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor-dependent endothelial cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(49):48848–48860. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310047200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Toyofuku T, et al. Dual roles of Sema6D in cardiac morphogenesis through region-specific association of its receptor, Plexin-A1, with off-track and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor type 2. Genes Dev. 2004;18(4):435–447. doi: 10.1101/gad.1167304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gallo G, Letourneau PC. Regulation of growth cone actin filaments by guidance cues. J Neurobiol. 2004;58(1):92–102. doi: 10.1002/neu.10282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lu X, et al. The netrin receptor UNC5B mediates guidance events controlling morphogenesis of the vascular system. Nature. 2004;432(7014):179–186. doi: 10.1038/nature03080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lamalice L, Le Boeuf F, Huot J. Endothelial cell migration during angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2007;100(6):782–794. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000259593.07661.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Pasquale EB. Eph-ephrin bidirectional signaling in physiology and disease. Cell. 2008;133(1):38–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Siekmann AF, Covassin L, Lawson ND. Modulation of VEGF signalling output by the Notch pathway. Bioessays. 2008;30(4):303–313. doi: 10.1002/bies.20736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]