Summary

Carbonated beverages are commonly available and immensely popular, but little is known about the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the perception of carbonation in the mouth. In mammals, carbonation elicits both somatosensory and chemosensory responses, including activation of taste neurons. We have now identified the cellular and molecular substrates for the taste of carbonation. By targeted genetic ablation and the silencing of synapses in defined populations of taste receptor cells, we demonstrate that the sour-sensing cells act as the taste sensors for carbonation, and show that carbonic anhydrase 4, a glycosyl-phosphatidyl inositol (GPI)-anchored enzyme, functions as the principal CO2 taste sensor. These studies reveal the basis of the taste of carbonation, and the contribution of taste cells in the orosensory response to CO2.

Humans perceive five qualitatively distinct taste qualities: bitter, sweet, salty, sour and umami. Sweet and umami are sensed by members of the T1R family of heteromeric guanine-nucleotide binding protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) (1–3), bitter stimuli are detected by T2R GPCRs (4–7), and sour is sensed by cells expressing the ion channel PKD2L1 (8–10). In the tongue, these receptors function in distinct classes of taste cells, each tuned to a specific modality (7, 8, 11, 12).

In addition to these well-known stimuli, the taste system appears to be responsive to CO2 (13, 14, 15). Mammals have multiple sensory systems that respond to CO2, including nociception (16, 17), olfaction (18), and chemoreception essential for respiratory regulation (19), yet the molecular mechanisms for CO2 reception remain poorly defined. Thus, we wondered how taste receptor cells (TRCs) detect and respond to carbonation.

We studied the electrophysiological responses of TRCs to CO2 by recording tastant-induced action potentials from one of the major nerves innervating taste receptor cells of the tongue (chorda tympani; 15); this physiological assay monitors the activity of the gustatory system at the periphery, and provides a reliable measure of taste receptor cell function (12, 20). Indeed, the taste system displayed robust, dose-dependent, and saturable responses to CO2 stimulation. The responses were evident for carbonated drinks (e.g. club soda), CO2 dissolved in buffer, and even direct stimulation of the tongue with gaseous CO2 (Fig. 1). In contrast, stimulation with pressured air did not elicit any gustatory response (Fig. 1).

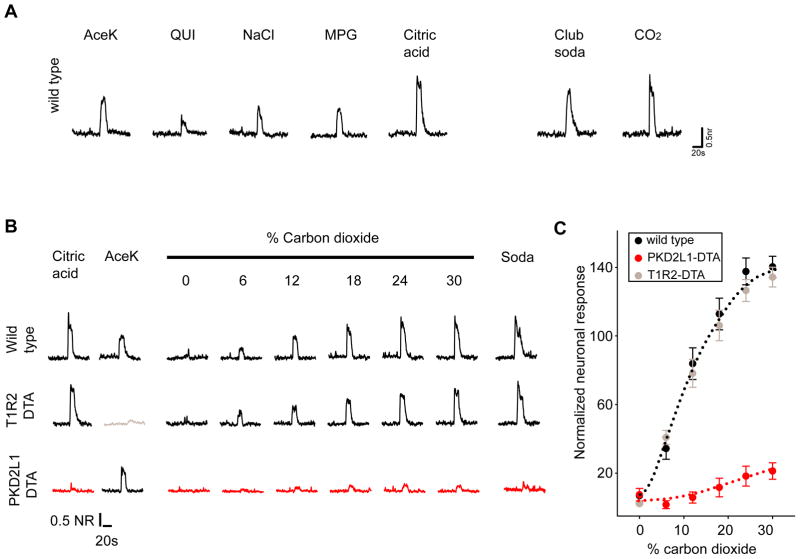

Fig. 1. PKD2L1-expressing sour-sensing cells mediate taste responses to carbonation.

(a) Wild-type mice show neural responses to carbonated solutions and carbon dioxide. Shown are chorda tympani nerve responses to control sweet (30mM acesulfameK, AceK), bitter (10mM quinine, QUI), salty (120mM NaCl), amino-acid (30mM mono potassium glutamate+0.5mM inosine mono phosphate, MPG), and sour (50mM Citric acid) stimuli as well as carbonated water (Club soda) and gaseous CO2 normalized to the responses to 250 mM NaCl (NR; see Materials and Methods). (b–c) Dose-response to CO2 in wild-type mice or in animals lacking sour-sensing cells (PKD2L1-DTA), and in control animals lacking sweet-sensing cells (T1R2-DTA). (c) Quantitation of carbon dioxide responses in wild-type (n=6), T1R2-DTA (n=4) and PKD2L1-DTA (n=5) animals. The values are mean ± sem of normalized chorda tympani responses.

To define the identity of the TRCs needed to taste carbonation we examined CO2 responses from engineered mice in which specific populations of TRCs were genetically ablated by targeted expression of attenuated diphtheria toxin (e.g. sweet-less, umami-less, sour-less mice, etc. Refs. 8, 21), and determined whether the taste system remained responsive to CO2. Selective ablation of sour sensing (i.e. PKD2L1-expressing) cells not only abolished all gustatory responses to acidic stimuli, but also eliminated responses to gaseous or dissolved CO2 (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S1). These results demonstrate that PKD2L1-expressing cells are essential for CO2 detection.

To identify a candidate CO2 receptor, we carried out gene expression profiling of sour cells. We reasoned that transcripts for genes involved in carbonation sensing should be enriched in PKD2L1-expressing cells, but be relatively rare in taste tissue in which PKD2L1 cells have been ablated. Thus, we conducted complementary microarray experiments using mRNA isolated from hand-picked green fluorescence protein (GFP)-labeled sour TRCs, and as a counter-screen, with mRNA from taste buds of animals lacking sour-sensing cells (PKD2L1-DTA mice Ref. 8). One gene, Car4, was particularly attractive as it was highly specific for PKD2L1-expressing cells versus other TRC types (Fig. 2), and most significantly, encoded carbonic anhydrase 4, a member of a large family of enzymes implicated in sensing, acting on, and responding to CO2 in various systems, including chemosensation (17–19, 22–28).

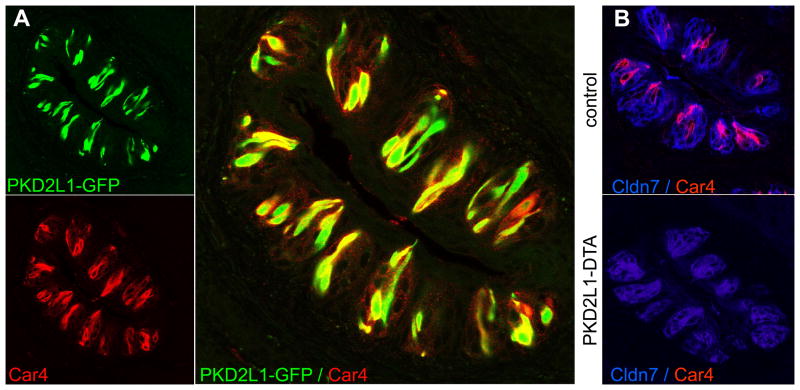

Fig. 2. Selective localization of carbonic anhydrase 4 to PKD2L1-expressing sour cells.

(a) Immunohistochemal staining of Car4 expression (lower panel, red) in taste buds of transgenic mice in which sour-sensing cells were marked by GFP fluorescence (PKD2L1-GFP; upper panel, green); large panel shows the superimposed double labeling. (b) Diphtheria toxin-mediated ablation of sour cells. Upper panel: Double label immunofluorescence with a marker of taste receptor cells, claudin 7 (Cldn7, blue), and antibodies to Car4 (red). Lower panel: labeling in PKD2L1-DTA mice stained as above. Shown are sections of foliate papillae, equivalent results were obtained in taste buds from other regions of the oral cavity (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Carbonic anhydrases (CAs) reversibly catalyze the conversion of CO2 into bicarbonate ions and free protons (29, 30). Car4 is a mammalian carbonic anhydrase that functions as an extracellular, GPI-anchored enzyme (30, 31). If Car4 is the CO2 sensor in the taste system then (i) pharmacological block of extracellular carbonic anhydrases should abolish CO2 taste responses, and (ii) a knockout of Car4 should selectively affect CO2 taste detection. We examined nerve responses in the presence of benzolamide, a membrane impermeant inhibitor of carbonic anhydrase (32, 33; see Supplementary Fig. S2). As predicted, gustatory (chorda tympani nerve) responses to CO2 were highly susceptible to carbonic anhydrase inhibition (Fig. 3). Next, we characterized Car4−/− mutant mice (32). Indeed, gustatory responses to CO2 were severely reduced in the mutants at all concentrations tested. However, responses to other taste stimuli, including sour, were unaltered. Thus, Car4 functions selectively as the main CO2 sensor in the taste system.

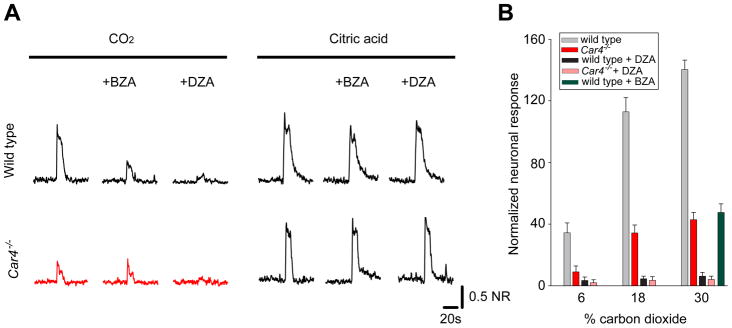

Figure 3. Requirement of carbonic anhydrase 4 for taste responses to carbon dioxide.

(a) Representative integrated chorda tympani responses to CO2 and sour stimulation in wild type or Car4−/− animals exposed to the cell-impermeant carbonic anhydrase inhibitor benzolamide (BZA) or the cell permeant, broad spectrum inhibitor dorzolamide (DZA). (b) Quantitation of carbon dioxide responses in wild-type and Car4−/− animals; mean ± sem (n=6). Green bar denotes wild type responses to 30% CO2 in the presence of BZA. See Supplementary Fig S5 for responses to other taste stimuli.

Given that CO2 taste sensing is completely eliminated in the absence of PKD2L1-expressing cells, we wondered why there are residual taste responses to CO2 in the Car4−/− animals. We hypothesized that the activity of additional carbonic anhydrases in these cells might provide the remaining activity. Notably, dorzolamide, a broadly acting, membrane permeable CA blocker (33; see Supplementary Figure S2) abolished the residual gustatory responses to CO2, even at the highest CO2 concentrations tested (Figure 3). Together, these studies strongly substantiate carbonic anhydrase as the CO2 receptor, and support a mechanism in which the products of Car4 activity at the extracellular surface of TRCs (i.e. HCO3− and H+) are the principal salient stimuli for detection of carbonation.

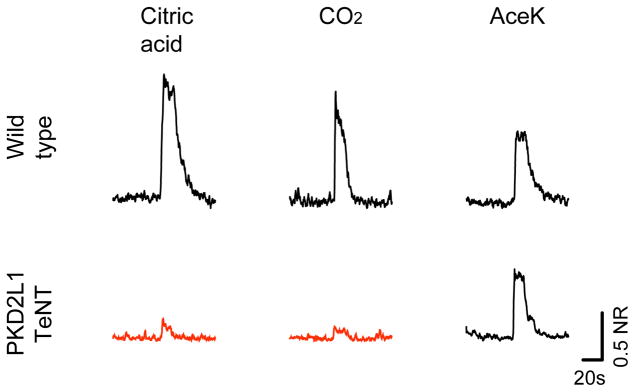

Bicarbonate does not stimulate TRCs (Supplementary Fig. 3), thus protons may be the relevant signal. Each of the basic taste modalities is mediated by distinct TRCs, with taste at the periphery proposed to be encoded via labeled lines (i.e. a sweet-line, a sour-line, a bitter-line, etc. 21). Given that Car4 is specifically tethered to the surface of sour-sensing cells, and thus ideally poised to provide a highly localized acid signal to the sour TRCs, we reasoned that carbonation might be sensed through activation of the sour labeled-line. A prediction of this postulate is that preventing sour cell activation should eliminate CO2 detection, even in the presence of wild-type Car4 function. To test this hypothesis we engineered animals in which the activation of nerve fibers innervating sour-sensing cells was blocked by preventing neurotransmitter release from the PKD2L1-expressing TRCs. In essence, we transgenically targeted expression of tetanus toxin light chain (TeNT, an endopeptidase that removes an essential component of the synaptic machinery Refs. 34–36) to sour-sensing TRCs, and then monitored the physiological responses of these mice to sweet, sour, bitter, salty, umami and CO2 stimulation. As predicted, taste responses to sour stimuli were selectively and completely abolished, whereas responses to sweet, bitter, salty and umami tastants remained unaltered (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 5). However, these animals also displayed a complete loss of taste responses to CO2 even though they still express Car4 on the surface of PKD2L1 cells. Together, these results implicate the extracellular generation of protons, rather than intracellular acidification (15), as the primary signal that mediates the taste of CO2, and demonstrate that sour cells provide not only the membrane anchor for Car4, but in addition serve as the cellular sensors for carbonation.

Figure 4. Requirement of PKD2L1-sour cells for the taste of carbonation.

Represeantative integrated chorda tympani responses to sour, sweet and CO2 stimuli in wild type, or in animals expressing TeNT in PKD2L1 sour-sensing taste receptor cells. See Supplementary Fig. S5 for responses to additional tastants and quantitative analysis.

Why do animals need CO2 sensing? CO2 detection could have evolved as a mechanism to recognize CO2-producing sources (18, 37), for instance to avoid fermenting foods. This view would be consistent with the recent discovery of a specialized CO2 taste detection in insects where it mediates robust innate taste behaviors (38). Alternatively, Car4 may be important to maintain the pH balance within taste buds, and might gratuitously function as a detector for carbonation only as an accidental consequence. Although CO2 activates the sour-sensing cells, it does not simply taste sour to humans. CO2 (like acid) acts not only on the taste system, but also in other orosensory pathways, including robust stimulation of the somatosensory system (17, 22), thus the final percept of carbonation may be a combination of these sensory inputs. Notably, the “fizz” and “tingle” of heavily carbonated water is often likened to mild acid stimulation of the tongue and in some cultures seltzer is even named for its salient sour taste (e.g. saurer Sprudel or Sauerwasser).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Wei Guo and Ann Becker for generation and maintenance of mouse lines, Dr. Mark Hoon for help in the initial phase of this work, Dr. E.R. Swenson for a generous gift of benzolamide, Dr. Martyn Goulding for Rosa26-flox-STOP-TeNT mice and Dr. Abdul Waheed for Car4 antibodies. We thank members of the Zuker laboratory for valuable comments. This research was supported in part by the intramural research program of the NIH, NIDCR (N.J.P.R.). C.S.Z. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- 1.Nelson G, et al. Cell. 2001;106:381. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nelson G, et al. Nature. 2002;416:199. doi: 10.1038/nature726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li X, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4692. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072090199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adler E, et al. Cell. 2000;100:693. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80705-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandrashekar J, et al. Cell. 2000;100:703. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80706-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsunami H, Montmayeur JP, Buck LB. Nature. 2000;404:601. doi: 10.1038/35007072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mueller KL, et al. Nature. 2005;434:225. doi: 10.1038/nature03352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang AL, et al. Nature. 2006;442:934. doi: 10.1038/nature05084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishimaru Y, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602702103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopezjimenez ND, et al. J Neurochem. 2006;98:68. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, et al. Cell. 2003;112:293. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00071-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao GQ, et al. Cell. 2003;115:255. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00844-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawamura AAY. In: Olfaction and taste II. HT, editor. Pergamon; New York: 1967. pp. 431–437. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komai M, Bryant BP, Takeda T, Suzuki H, Kimura S. In: Olfaction and Taste XI. Kurikara SNK, Ogawa H, editors. Springer-Verlag; Tokyo: 1994. p. 92. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lyall V, et al. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;281:C1005. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.281.3.C1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dessirier JM, Simons CT, O’Mahony M, Carstens E. Chem Senses. 2001;26:639. doi: 10.1093/chemse/26.6.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simons CT, Dessirier JM, Carstens MI, O’Mahony M, Carstens E. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8134. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-18-08134.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu J, et al. Science. 2007;317:953. doi: 10.1126/science.1144233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lahiri S, Forster RE., 2nd Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2003;35:1413. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(03)00050-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dahl M, Erickson RP, Simon SA. Brain Res. 1997;756:22. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandrashekar J, Hoon MA, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. Nature. 2006;444:288. doi: 10.1038/nature05401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komai M, Bryant BP. Brain Res. 1993;612:122. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller LG, Miller SM. J Fam Pract. 1990;31:199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Graber M, Kelleher S. Am J Med. 1988;84:979. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(88)90091-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown D, Garcia-Segura LM, Orci L. Brain Res. 1984;324:346. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(84)90046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daikoku H, et al. Chem Senses. 1999;24:255. doi: 10.1093/chemse/24.3.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bottger B, Finger TE, Bryant B. Chem Senses. 1996;21:580. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akiba Y, et al. Gut. 2008;57:1654. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.144378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Supuran CT. Curr Pharm Des. 2008;14:603. doi: 10.2174/138161208783877884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sly WS, Hu PY. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okuyama T, Waheed A, Kusumoto W, Zhu XL, Sly WS. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;320:315. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(95)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah GN, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:16771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508449102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vullo D, et al. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:971. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.12.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamamoto M, et al. J Neurosci. 2003;23:6759. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-17-06759.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu CR, et al. Neuron. 2004;42:553. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y, et al. Neuron. 2008;60:84. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suh GS, et al. Nature. 2004;431:854. doi: 10.1038/nature02980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fischler W, Kong P, Marella S, Scott K. Nature. 2007;448:1054. doi: 10.1038/nature06101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.