Summary

How is visual space represented in cortical area MT+? At a relatively coarse scale, the organization of MT+ is debated: Retinotopic, spatiotopic, or mixed representations have been proposed. However, none of these entirely explains perceptual localization of objects at a fine spatial scale—a scale relevant for tasks like navigating or manipulating objects. For example, perceived positions of objects are strongly modulated by visual motion: stationary flashes appear shifted in the direction of nearby motion. Does spatial coding in MT+ reflect these shifts in perceived position? We performed an fMRI experiment employing this “flash-drag effect”, and found that flashes presented near motion produced patterns of activity similar to physically shifted flashes in the absence of motion. This reveals a motion-dependent change in the neural representation of object position in human MT+, a process that could help compensate for perceptual and motor delays in localizing objects in dynamic scenes.

Introduction

One of the best-studied cortical visual areas in primates is the middle temporal complex (area MT+). Despite a large and comprehensive literature, the way that MT+ represents visual space is debated. Area MT in the macaque monkey, and its human homologue hMT+, has been shown to represent positions coarsely in a retinotopic manner (Gattass and Gross, 1981; Huk et al., 2002; Wandell et al., 2007). Detailed mapping procedures revealed up to four retinotopic maps collectively forming the MT+ complex in humans (Dukelow et al., 2001; Amano et al., 2009; Kolster et al., 2010). Recently, some researchers have proposed that MT+ contributes to stable perception across eye movements by representing object locations in a world-centered, or spatiotopic coordinate frame (Melcher and Morrone, 2003; d'Avossa et al., 2007; Ong et al., 2009; Crespi et al., 2011). Others have only found evidence for retinotopic, and not spatiotopic coordinate frames in MT+ (Gardner et al., 2008; Morris et al., 2010; Hartmann et al., 2011; Ong and Bisley, 2011; Au et al., 2012; Golomb and Kanwisher, 2012), a difference that may be due to the location of covert visual attention (Gardner et al., 2008; Crespi et al., 2011). Most of these studies investigated spatial representations in MT+ at a relatively coarse spatial scale. However, during routine activities such as navigating around obstacles or manipulating objects, the visual system's ability to localize objects on a fine spatial scale defines our ability to interact successfully with the world.

At a population level, MT+ represents fine-scale spatial information, discriminating position shifts of a third of a degree of visual angle or less (Fischer et al., 2011). At these fine scales, a number of visual phenomena show remarkable dissociations between the perceived position of an object and its retinal or spatial position: for example, motion in the visual field can shift the perceived positions of stationary or moving objects (Fröhlich, 1923; Ramachandran and Anstis, 1990; De Valois and De Valois, 1991; Nijhawan, 1994; Whitney and Cavanagh, 2000; Krekelberg and Lappe, 2001; Whitney, 2002; Eagleman and Sejnowski, 2007). Disrupting activity in area MT+ by transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) reduces these motion-induced mislocalization illusions (McGraw et al., 2004; Whitney et al., 2007; Maus et al., 2013). This is strong evidence for an involvement of MT+ in these illusions, yet it does not resolve questions about the underlying spatial representation in area MT+. However, these findings raise the possibility that MT+ represents fine-scale positional biases induced by visual motion, and that spatial representations in MT+ are dependent on visual motion.

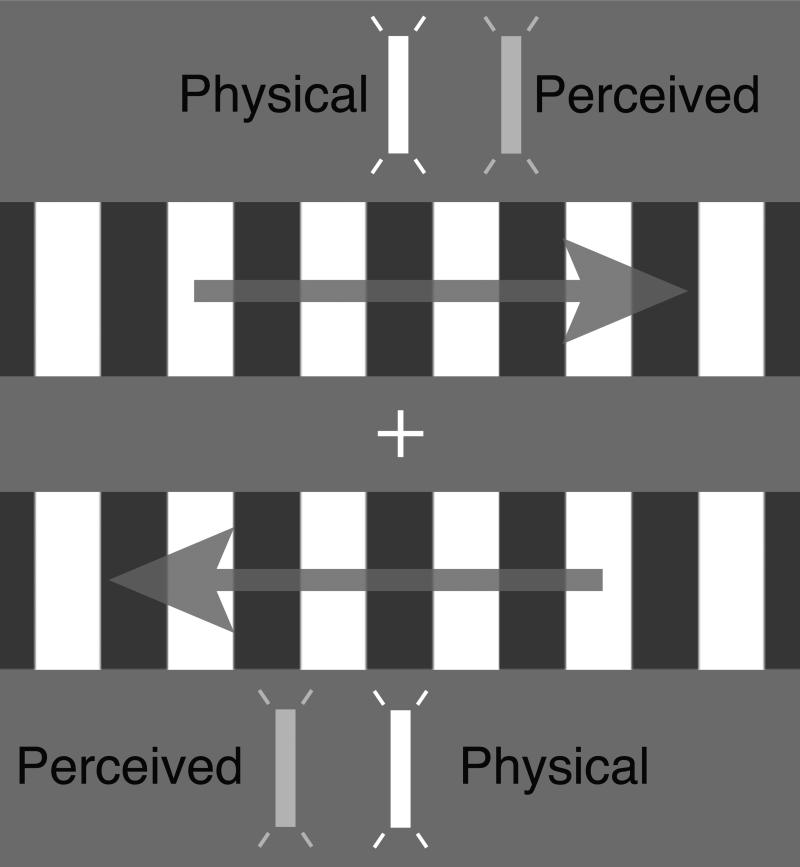

Here, we investigated whether position representations in area MT+ are modulated by motion using the flash-drag effect (Whitney and Cavanagh, 2000; Tse et al., 2011; Kosovicheva et al., 2012). When flashes are presented in the vicinity of motion, they appear to be ‘dragged’ in the direction of nearby motion and are perceived in illusory positions distinct from their physical (retinal) position (Fig. 1). Our aim was to test whether position coding in MT+ reflects these perceptual distortions introduced by visual motion. We found that flashed objects presented near visual motion produce patterns of BOLD activity that are similar to patterns of activity generated by physically shifted flashes in the absence of motion. This reveals a motion-dependent change in the neural representation of object position in human MT+.

Figure 1. The flash-drag effect.

Visual motion can change the perceived position of brief flashes presented nearby: they appear “dragged” in the direction of motion.

Results

The flash-drag effect

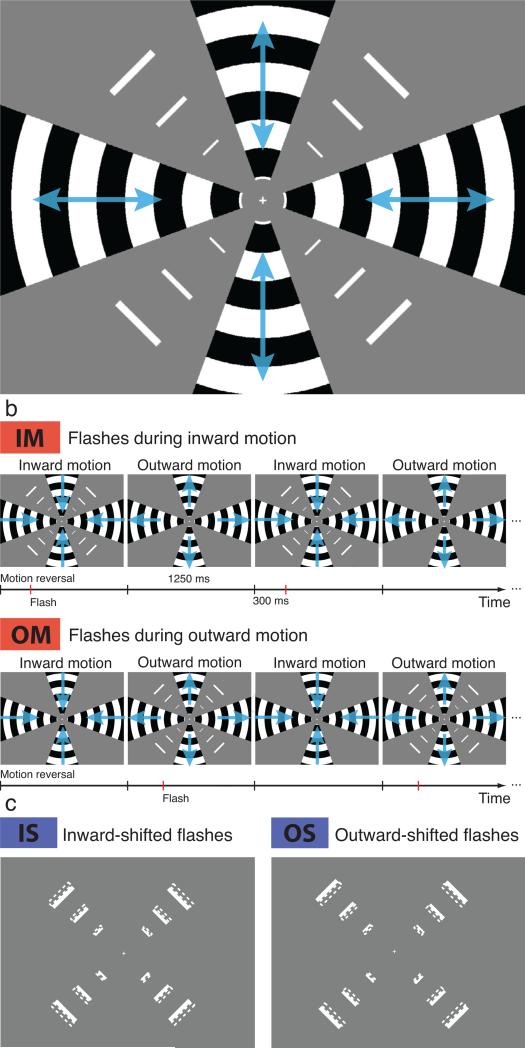

First, we psychophysically quantified the magnitude of the perceptual shift in our flash-drag stimulus (Fig. 2a). We presented a drifting grating in wedges along the horizontal and vertical visual field meridians, oscillating between inward and outward motion. In the spaces between the gratings, we presented flashed bars either during inward or during outward motion (Fig. 2b). There were three flashed bars in each visual field quadrant, scaled in size by their eccentricity (see Experimental Procedures). The flashes were presented in the same physical positions on all trials. After three presentations of the flashes, we presented comparison flashes whose positions were manipulated, shifted inward or outward by 0, 1, or 2 bar widths on separate trials. Four participants performed a method of constant stimuli task judging whether the comparison flashes appeared shifted inward or outward relative to the flashes displayed while motion was present. Aggregate psychometric functions for this experiment are shown in Fig. S1. Flashes presented during inward motion were perceived more centrally (closer to the fovea) than flashes presented during outward motion. In other words: flashes appeared to be shifted, or “dragged”, in the direction of the surrounding motion. The point of subjective equality (PSE) was shifted by 0.82 bar widths inward for flashes presented during inward motion, and 0.16 bar widths outward for flashes during outward motion. Bootstrapped 95%-confidence intervals of PSEs were not overlapping (horizontal error bars in Fig. S1), and every individual observer showed a difference between PSEs in the expected direction.

Figure 2. Stimulus and conditions in the fMRI experiment.

(a) Gratings along the visual field meridians were oscillating between inward and outward motion, flashes were presented once per cycle in the space between the gratings. (b) IM and OM conditions both contained inward and outward motion, only the timing of the flashes relative to the phase of the oscillating motion changed. (c) In IS and OS conditions the physical position of flashes was shifted inward or outward by 1 bar width. See also Figure S1.

Our stimuli were optimized for use in an fMRI experiment (i.e., flashes were presented repeatedly and distributed throughout the visual field to generate robust BOLD response). Participants were instructed not to attend to any one flash location specifically. For these reasons, we measured a relatively small flash-drag effect compared to other studies (e.g. Whitney and Cavanagh, 2000; Tse et al., 2011; Kosovicheva et al., 2012), but the perceived shift of the flashes was robust and reliable. In the fMRI experiment, the observers’ perception of the flash-drag effect was not explicitly probed; rather, subjects performed an attentionally demanding task at the fixation point to rule out possible attentional confounds. Our goal was to investigate whether visual motion leads to changes in the spatial representation of the flashes, regardless of the observer's task and attentional engagement.

fMRI experiment

The fMRI experiment consisted of six different stimulation conditions, presented in randomly interleaved blocks of 12 s duration: Fixation only (F), Motion only (M), Flashes during Inward Motion (IM), Flashes during Outward Motion (OM), physically Inward-Shifted flashes only (IS), and physically Outward-Shifted flashes only (OS) (see Fig. 2b and c). In the conditions IM and OM, the flashes were presented either during inward or during outward motion, respectively, exactly once per oscillation cycle of the moving gratings. In each block, the motion was identical between these two conditions and the flashes were always presented in the same positions; only the timing of the flashes relative to the direction of motion was changed. In the IS and OS conditions, the position of each flash was shifted inward or outward (toward or away from the fovea, respectively) by the width of one flashed bar and thus roughly matched the perceptual mislocalization measured in the psychophysical study.

In all participants, we localized area MT+ in separate localizer runs by a contrast of moving and stationary random dot stimuli, as well as early visual areas V1 – V3A by a standard retinotopic mapping procedure (see Experimental Procedures). Fig. S2 shows the boundaries between retinotopic areas and the outline of MT+ on an “inflated” visualization of the cortical sheet for one participant. Fig. S2 also shows activity in response to the flashes alone (IS and OS) or the moving gratings alone (M). These maps were generated by fitting a General Linear Model (GLM) to the functional data and contrasting IS and OS vs. F (baseline) and M vs. F, respectively, with a False Discovery Rate threshold set at q = 0.05.

The flashes were centered in each visual field quadrant, and, accordingly, activity can be observed near the centers of quarterfield representations in areas V1-V3 (Fig. S2a). Since three flashes at different eccentricities were presented in each quadrant, we did not expect to see a clearly localized peak of BOLD activity at a single eccentricity in the retinotopic map. Instead, we pursued a sensitive multi-voxel pattern analysis strategy that utilizes information from a large number of voxels within a Region of Interest (ROI, see below).

The motion-only stimulus (M) consisted of four 40°-wedges along the horizontal and vertical field meridians containing a high-contrast moving radial square-wave grating (Fig. 2a). This stimulus generated robust activity throughout the visual cortex, which, not surprisingly, spread to portions of the cortical representation that did not correspond to stimulated locations (Fig. S2b).

Multi-voxel pattern analysis

The conditions of main interest are IM and OM, where physically identical flashes were presented during either inward or outward motion of the gratings, respectively. Because we were interested in the representations of the flashes, and the motion in IM and OM conditions was identical, we computed voxel-wise differences of GLM beta values between IM and OM conditions. This isolated the effect that the direction of motion in the grating wedges had on the representation of the flashes. It is of crucial importance here that stimulation in the moving wedges was identical between IM and OM conditions: The gratings always oscillated between inward and outward motion; also, the flashes were always presented in the same physical position. Only the timing of the flashes relative to the motion differed between IM and OM conditions; they were presented either during inward or outward motion. The only activity remaining in these difference maps (IM–OM) reflects the influence of motion direction on the representation of the flashes.

Similarly we computed the voxel-wise difference between GLM beta values for IS and OS (flashes physically shifted inward or outward, respectively). This resulted in a map (IS–OS) reflecting the differential representation of the physically shifted flashes.

We assessed the statistical similarity of the BOLD activity pattern evoked by illusory shifted flashes in the flash-drag effect to that evoked by physically shifted flashes. For this, we computed the correlation between the IM–OM difference map (flashes presented during inward minus outward motion) and the IS–OS map (inward minus outward shifted flashes). As mentioned above, IM and OM conditions consist of spatially identical visual stimulation; if MT+ represents object positions in a strictly retinotopic manner, one would expect a difference map of these two conditions to only consist of noise. If, however, motion causes flashes to be represented similarly to physically shifted flashes in MT+, we expect a positive correlation between these two difference maps across a population of voxels; i.e., the physical shift of flashes between IS and OS conditions predicts how flashes are represented in IM and OM conditions. Any reliably positive correlation is evidence for similarity in the representations of illusory shifted flashes and physically shifted flashes in the population of voxels.

Fig. 3 demonstrates this analysis in area MT+ for one participant. We selected an ROI of voxels representing the locations of the flashes by a GLM contrast of IS and OS vs. F (flashes vs. fixation; p < 0.01, Bonferroni corrected). We also repeated the analysis with independently defined ROIs and obtained the same results (see Experimental Procedures). Fig. 3a shows the difference maps, IM–OM and IS–OS, computed as described above, within this ROI. The difference values for each voxel are shown on a scatter plot in Fig. 3b. For the ROI in MT+ in this participant, consisting of a total of N = 350 voxels, there is a positive correlation between the two difference maps (r = 0.729), indicating similarity between the patterns of activity. Correlation coefficients r were transformed to Fisher z’ scores to enable linear comparisons (z’ = 0.928).

Figure 3. Multi-voxel pattern analysis strategy.

(a) We calculated differences between flashes presented during inward and outward motion (IM – OM) and flashes in physical positions shifted inward and outward (IS – OS). Insets show maps for MT+ in one subject (color code in b). (b) These difference maps were correlated with each other for a ROI responding to the flashes within area MT+ (one subject shown; each point on the correlation plot is one voxel within MT+). A positive correlation signifies a similar representation of illusorily and physically shifted flashes. (c) Histogram of resulting correlation values for the same voxels after random shuffling of condition labels. See also Figure S2.

To demonstrate that positive correlations are neither present everywhere in the brain nor an artefact of our analysis strategy, we conducted the following two analyses. First, we repeated the same correlation analysis for 1000 sets of random voxels, picked (with replacement) from all cortical grey matter areas covered by our scan volume. Random sets of equal size (350 voxels) showed no correlation (mean z’ = 0.000, SD = 0.055), and no single random set yielded higher correlations than MT+ (p < 0.001). Similar results were obtained for randomly selected contiguous grey matter regions from all brain areas. One thousand randomly selected contiguous ROIs of the same size from all grey matter areas showed only small correlations (mean z’ = 0.095, SD = 0.011), significantly lower than the ROI in MT+ (p = 0.005).

We further assessed the significance of correlations by a permutation test. Using the same functional data, we randomly shuffled the condition labels of the IM and OM conditions 1000 times. With this reshuffling of IM and OM condition labels, the information about the motion direction at the time of the flashes is lost, while keeping slow temporal correlations and information about the presence of motion in the stimulus in place. Applying the same analysis (fitting a GLM, generating difference maps of IS–OS and IM–OM, and calculating correlations as above) resulted in a null distribution of correlation coefficients centered around zero (Fig. 3c). The correlation score obtained with the original condition labels (indicated by the red vertical line) falls in the positive extreme end of the distribution (p = 0.013).

The mean Fisher z’ value across subjects for correlations between IS–OS and IM–OM in MT+ was 0.370 (SD = 0.147). We assessed significance at the group level by a bootstrap procedure that tested whether mean correlations in the group were higher than expected under the null hypothesis, comparing the actual correlations to the those obtained from shuffling condition labels (see Experimental Procedures). The correlation in MT+ was highly significant (p = 0.005), indicating that the representation of the flashes in MT+ is biased in the direction of the perceptual shift. Similarly high correlations were found in area V3A (z’ = 0.385, p = 0.050), a mid-level motion-sensitive area that has been implicated in other motion-induced positions shifts (Maus et al., 2010). Earlier areas showed positive but non-significant correlations (V1: z’ = 0.157, p = 0.111; V2: z’ = 0.027, p = 0.437; V3: z’ = 0.100, p = 0.274; see Fig. 4 and S3). The pattern of results across visual areas cannot be explained by different numbers of voxels (Pearson's r = -0.151, p = 0.434) or different signal-to-noise ratios (r = -0.208, p = 0.279).

Figure 4. Results of the multi-voxel pattern analysis.

Mean correlation scores (n = 6) are shown for ROIs in V1-V3A and MT+. Errorbars are bootstrapped 95%-confidence intervals. See also Figure S3.

In an additional control analysis we tested whether spatial representations in MT+ are of sufficient resolution to pick up small position shifts. We employed a multi-voxel pattern classification approach, using a Support Vector Machine (SVM) to classify the activity patterns from single blocks as stemming from IS or OS stimulation conditions, and separately for IM and OM conditions. Feature selection and training of the SVM was done on a different subset of the data than the evaluation of classification performance, and cross-validated 200 times for different sets of training and test data (see Experimental Procedures). This SVM approach classified IS and OS conditions accurately on average on 67.1% of blocks, and 57.5% of IM and OM blocks. Statistical significance of classification performance was assessed by a permutation test, randomly shuffling block condition labels 1200 times and repeating the same analysis on shuffled labels. Classification performance was significantly better than expected from this empirical null distribution for IS v OS (p = 0.0025) and marginally better for IM v OM (p = 0.0608). These additional results confirm that spatial representations in MT+ and our MRI recording sequence are of sufficient resolution to measure small but reliable spatial shifts.

Attention

Throughout the fMRI experiment, participants performed an attentionally demanding detection task, responding with a key press to a brief contrast decrement of the fixation cross. We analyzed proportions of correctly detected contrast decrements and reaction times (RT) in each of the stimulation conditions to test for differences of attentional engagement between conditions. The fixation (F) and motion-only (M) conditions, as well as IM and OM, led to equivalent performance, with between 87.7 and 89.3% correct responses and RT between 0.53 and 0.57 s. Crucially, performance in IM and OM conditions was no worse than in the baseline condition F (paired one-tailed t-tests, RT: t(3) < -1.94, p > 0.926; accuracy: t(3) < 0.862, p > 0.272), ruling out attention to the positions of the flashes in the motion conditions as a cause for our effect. Performance was slightly (non-significantly) worse in the IS and OS conditions (76.8 – 78.1% correct; paired two-tailed t-tests, t(3) > 1.55, p < 0.219) and reaction times were longer (0.93 – 0.96 s; t(3) > 14.2, p < 0.002). However, attentional differences between motion conditions and flashes-only conditions would not affect our main analysis, because we calculated differences in activation between IS and OS (and separately IM and OM) to assess correlations in patterns of activity. Performance and RTs between IS and OS (and between IM and OM) were equivalent (IS vs. OS: t(3) < 2.58, p > 0.082; IM vs. OM: t(3) < 0.613, p > 0.584).

Discussion

Here we provide evidence that visual motion biases the fine-scale cortical localization of briefly presented objects in human MT+. The spatial coding of perceptually shifted objects (as a result of nearby motion) is similar to the coding of physically shifted objects in MT+. This representational change is small and would be hard to detect as a shift in the peak BOLD response within a retinotopic map with conventional analytic methods. Instead we employed multiple flashes distributed throughout all four quadrants of the visual field and a sensitive analysis of multi-voxel patterns. By calculating correlations between difference maps—the differences induced by a perceptual shift in the flash-drag effect and by physically different retinal positions—we were able to show that, in area MT+, the representation of stationary flashes in the flash-drag effect is biased in the direction of the motion.

The nature of spatial representations within area MT+ is debated. Some propose that MT+ represents positions in world-centered coordinates (Melcher and Morrone, 2003; d'Avossa et al., 2007; Ong et al., 2009; Crespi et al., 2011), others maintain that MT+ is strictly retinotopic (Gardner et al., 2008; Hartmann et al., 2011; Au et al., 2012; Golomb and Kanwisher, 2012). Attention may be a key factor in determining which reference frame dominates in a given experiment (Gardner et al., 2008; Crespi et al., 2011). Our results go beyond these accounts, because flashes in identical physical locations (both in retinal and spatial coordinates) are represented differently in MT+ depending on the direction of visual motion present, and we rule out that differences in attention can explain this effect (see below). Therefore, at a fine spatial scale—one that is critical for perception and action—MT+ incorporates information about visual motion in the scene into its position representation. An intriguing possibility is that spatial representations in MT+ are based on an integration of visual motion and other cues (such as retinal position and gaze direction). Consistent with this notion, a previous report has shown that patterns of fMRI activity in MT+ are highly selective for perceived object positions on a trial-by-trial basis (Fischer et al., 2011). Here, we systematically manipulated perceived positions of objects using a well-known motion-induced position illusion, and demonstrated that position coding in MT+ is modulated by motion in a manner consistent with the perceived positions of the objects.

Our manipulation of perceived position was on a relatively fine spatial scale. Previous studies investigating spatial representations in MT+ have used large-scale manipulations of spatial positions, e.g., with stimuli presented in either the left or right visual fields (d'Avossa et al., 2007; Golomb and Kanwisher, 2012). Here we measure much more fine-grained spatial representations, which are nonetheless of the utmost importance for successful perception and action in dynamic environments. Localization errors of just fractions of a degree can mean the difference between, for example, successfully hitting or missing a baseball, or avoiding a pedestrian while driving. At these fine spatial scales, localization errors due to neural delays of moving objects would have dramatic effects.

Motion-induced shifts in represented positions might improve the spatial accuracy of perception (Nijhawan, 1994, 2008) and visually guided behavior (Whitney et al., 2003; Whitney, 2008; Whitney et al., 2010) by compensating for neural delays in signal transmissions and coordinate transformations when localizing objects in dynamic scenes. Indeed, large-field visual motion, of the sort that MT+ is selective for, biases reaching movements in a manner that makes reaching more accurate (Whitney et al., 2003; Saijo et al., 2005); interfering with neural activity in MT+ using TMS reduces the beneficial effects of background visual motion on reaching (Whitney et al., 2007). More recently, Zimmerman and colleagues (2012) found that visual motion biases saccade targeting, consistent with the idea that background visual motion is used for predictively updating target positions for saccades, as well as for perception and visually guided reaching.

There are several neurophysiologically plausible mechanisms that could serve to shift the representation of objects in the direction of visual motion. For example, neurophysiological recordings in visual cortex of monkey (Sundberg et al., 2006) and cat (Fu et al., 2004) have shown that neurons’ spatial receptive field properties can change and shift in response to moving stimuli. Even in the retinae of salamanders and rabbits, receptive fields of ganglion cells are known to shift towards a moving stimulus, effectively anticipating stimulation (Berry et al., 1999; Schwartz et al., 2007). These single-unit electrophysiological results were obtained with moving stimuli, and there are obvious differences between the BOLD signal and single unit recordings (e.g. Logothetis, 2003). However, the fMRI results in the present study point to similar motion-induced changes in population receptive fields in MT+ that affect spatial coding even for briefly presented static objects.

Previous single unit studies in monkeys have found that MT+ receptive fields also shift with attention, even when no motion is present (Womelsdorf et al., 2006; Womelsdorf et al., 2008). However, attention cannot explain our pattern of results. The flash-drag effect is usually measured in psychophysical paradigms requiring observers to attend to the flash locations to be able to make perceptual judgments (Whitney and Cavanagh, 2000). In the present experiments we presented observers with a stimulus that normally causes misperceptions of flash positions, but did not require them to make perceptual judgments. Instead, observers performed an attentionally demanding task at the fixation point, and we analyzed the representation of passively viewed flashes in MT+. Performance for trials with inward and outward-shifted flashes was equivalent to baseline trials, indicating no attentional capture of the flashes presented during motion. Thus the representational change we found is not due to an effect of voluntary or involuntary attention to different spatial locations, nor does it require attention to be detectable in MT+.

The motion-dependent position coding in MT+, revealed here, may play a causal role in perceiving object positions. Using TMS over area MT+, several studies have shown a reduction of motion-induced mislocalization phenomena during and after stimulation of MT+ (McGraw et al., 2004; Whitney et al., 2007; Maus et al., 2013). These studies show the causal necessity of activity in MT+ for perceptual localization. However, our present results go far beyond those studies. Previous TMS experiments could not address the spatial representation of objects in MT+, whether it is modulated by motion, whether MT+ causes changes in position representations in another area, or whether it actually represents shifted positions.

The present experiments provide the first evidence that motion-induced position shifts are represented by population activity in MT+. This provides new insight into the way visual space is represented in area MT+ and how it contributes to visual localization of objects for perception and action.

Experimental Procedures

Participants

Six participants (1 female; mean age 26.5, range 22-29) volunteered to take part in the study, including two of the authors. Four of the participants also took part in the psychophysical study outside of the scanner. All participants were informed about the procedure, thoroughly checked for counter-indications for MRI, were neurologically healthy, and had normal or corrected-to-normal visual acuity. The study was approved by the University of California Davis Institutional Review Board and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

MRI Acquisition

The MRI scans were performed with a Siemens Trio 3T MR imaging device with an 8-channel head coil at the UC Davis Imaging Research Center in Sacramento, CA. Each participant underwent a high-resolution T1-weighted anatomical scan using an MPRAGE sequence with 1 × 1 × 1 mm voxel resolution. Functional scans were obtained with a T2*-weighted echo planar imaging sequence (TR = 2000 ms, TE = 26 ms, FA = 76°, matrix = 104 × 104). The 28 slices (in plane resolution 2.1 × 2.1 mm; slice thickness 2.8 mm; gap between slices 0.28 mm) were oriented approximately parallel to the calcarine sulcus and covered all of occipital and most of parietal cortex, while missing inferior parts of temporal and frontal cortices.

Stimulus Presentation

In the psychophysics study, stimuli were presented on a CRT monitor (spatial resolution 1024 × 768 pixels) running at 75 Hz refresh rate. Participants viewed the screen from 57 cm distance with their heads immobilized on a chin rest. In the MRI scanner, stimuli were back-projected onto a frosted screen at the foot end of the scanner bed using a Digital Projection Mercury 5000HD projector running at 75 Hz refresh rate. Participants viewed the stimuli via a mirror mounted on the head coil. All stimuli were generated using Matlab (The Mathworks, Inc.) and the Psychtoolbox extensions (Brainard, 1997; Pelli, 1997).

Stimuli

The basic layout of the stimulus is shown in Fig. 2a. The moving stimulus was a concentric square wave grating (spatial frequency 0.4 cycles per degree), visible only in wedges spanning an angle of 40° along the horizontal and vertical visual field meridians. White and black parts of the grating had a luminance of 75.8 cdm-2 and 3.51 cdm-2, respectively (Michelson contrast = 91%). The grating's carrier wave drifted within the wedges at a constant speed of 9.1 degrees per second (8 pixels per frame) and reversed direction every 1.25 s. The central area, 1.8 degrees around the fixation cross, and the area between the grating wedges was uniform grey (luminance 25.3 cdm-2). White flashes could be presented in the areas between the gratings. To maximize BOLD response to the flashes, we presented several flashes, three in each sector of the visual field, scaled in size with eccentricity (see Fig. 2a). The innermost flashes at 2.9 degree eccentricity measured 0.9 × 0.1 degrees, the next flashes at 5.4 degrees 1.7 × 0.2 degrees, and the outermost flashes at 7.9 degrees 2.5 × 0.3 degrees. The flashes were presented 300 ms after a reversal of motion direction in the gratings and lasted 2 refresh frames (26.7 ms).

Psychophysics Procedure and Analysis

To verify that our stimuli gave rise to the perception of the flash-drag effect, we performed a psychophysical study outside of the scanner. We presented 3 cycles of the grating wedges oscillating between inward and outward motion with flashes presented once per cycle either during inward or during outward motion. Immediately afterwards, the gratings remained stationary, and the flashes were presented one more time in physically altered locations. All flashed bars could be shifted inward or outward by one or two times their own width. Observers were asked to judge whether on the final presentation the flashes appeared spaced closer or wider (shifted inward or outward) than when presented during the motion, without attending to any one flash location in particular. Four observers performed 100 trials in a Method of Constant Stimuli design (2 motion directions during flashes [inward/outward] × 5 physical comparison flash positions [shifted by -2, -1, 0, 1, 2 bar widths] × 10 repetitions).

To analyse this experiment, we fitted cumulative Gaussian functions to observers’ responses and estimated PSEs, where the flashes in physically shifted positions were perceived in the same positions as those presented during motion, and confidence intervals for these values (Wichmann and Hill, 2001a, b).

fMRI Procedure

In the fMRI experiment, there were six different stimulation conditions: Fixation only (F), Motion only (M), Flashes during Inward Motion (IM), Flashes during Outward Motion (OM), Inward-shifted Flashes only (IS), and Outward-shifted Flashes only (OS). In the conditions with flashes during motion (IM and OM), the flashes were presented either during inward drift or during outward drift, exactly once per oscillation cycle, 300 ms after the reversal of motion direction in the gratings (Fig. 2b). The phase of the grating's dark and light bars, and the phase of the motion direction oscillating between inward and outward at the start of each trial was randomized. Overall, the motion was equated between these two conditions; only the timing of the flashes relative to the direction of motion was changed. In the Flashes-only conditions (IF and OF), the position of each flash was shifted inward or outward by the width of one bar (i.e., scaled by eccentricity; Fig. 2c) from the original position in the IM and OM conditions. Flashes were repeated continuously at 4 Hz (i.e., flashed every 0.25 s).

We used a blocked design: each stimulus condition was shown continuously for 11.5 seconds (with a 0.5 second fixation-only period before the next stimulus condition started). Each subject completed a scan session containing 6 runs of the main experimental stimuli, consisting of 4 repetitions of F, M, IS, and OS conditions, and 7 repetitions of IM and OM conditions. All stimulus conditions were presented in randomly interleaved order. Each run started and ended with 4 seconds of fixation only. Throughout a run, i.e., during all conditions, participants performed an attentionally demanding task at the central fixation cross. The white fixation-cross (0.3 × 0.3 degrees) decreased contrast randomly every 4 - 8 s (at least once during every stimulation block). Participants had to press a button on the response box as soon as they detected each contrast decrement. Due to technical difficulties with the response boxes, responses could not be recorded from one participant and only in half of the runs from 2 more participants.

To define cortical areas we performed independent localizer runs. To identify area MT+ we presented a stimulus consisting of low contrast black and white random dots on a mid-grey background that were either stationary for the duration of a block, or oscillated between centrifugal and centripetal motion (speed of motion: 7 degrees/sec, rate of oscillation: 1.25 Hz). To define the boundaries of retinotopic maps V1 – V3A in early visual cortex we presented bow tie flickering checkerboards along either the horizontal or vertical visual field meridian, spanning 15° opening angle and flickering at 4 Hz. These stimuli allowed us to identify the meridians separating early retinotopic areas in visual cortex.

fMRI Analysis

The BrainVoyager QX software package (BrainInnovation B.V.) was used for preprocessing and visualization of the data. Functional data from each run were corrected for slice acquisition time and head movements, and spatially co-registered with each other. Voxel timecourses were temporally high-pass filtered with a cut-off at 3 cycles per run (0.008 Hz). We did not perform spatial smoothing. Functional data were then aligned with the high-resolution anatomical scan, spatially normalized into Talairach space (Talairach and Tournoux, 1988), and subsampled into isotropic voxels of 2 × 2 × 2 mm. We further separated white from grey matter and used the resulting boundary to “inflate” each brain hemisphere for better visualization of the cortical sheet. Spatial normalization was performed solely to facilitate comparison of coordinates between subjects. All analysis was performed on single subjects and there was no averaging of functional imaging data between subjects.

The localizer runs were analyzed by fitting a GLM using BrainVoyager's canonical hemodynamic response function. We corrected for serial correlations by removing first-order autocorrelations and refitting the GLM. For the delineation of areas V1 to V3A we contrasted stimulation conditions of horizontal vs. vertical meridians and drew lines by hand along the maxima and minima of the unthresholded t-map on the inflated representation of visual cortex. Area MT+ was defined using a contrast of moving vs. static dots.

All other analysis steps were performed using custom code in Matlab. For the main experiment, we fit a GLM to each voxel's concatenated timecourse from all six runs using a boxcar model of the six stimulation conditions (F, M, IM, OM, IS, OS) convolved with a canonical hemodynamic response function and corrected for serial autocorrelation. Beta values from the GLM are used as an index of a voxel's activation in response to each stimulation condition. We then computed two difference maps: IM-OM and IS-OS (see Fig. 3a). The stimulation due to the moving wedges is identical in the IM and OM conditions, and flashes are always presented in identical positions. The only physical difference between IM and OM is in the timing of the flashes relative to the phase of the motion. The second difference map (IS-OS) represents the difference in activations resulting from the two physical flash positions. Similar to other multi-voxel pattern analyses (e.g. Haxby et al., 2001), we determine how similar a physical shift of the flashes is to the motion's influence on the flash by correlating the values from the two difference maps IM-OM and IS-OS for a given set of voxels. The correlation approach is evaluating the similarity of the pattern of activity within a ROI rather than individual voxel's activation values. Pearson's correlation coefficients r were converted to Fisher z’ scores to facilitate linear comparisons of values.

We performed this correlation analysis for ROIs representing the positions of all flashes within area MT+ and early cortical maps (V1, V2, V3, V3A). To define ROIs, we selected voxels with significant BOLD responses (p < 0.01, Bonferroni corrected) in response to the two flashes-only conditions (IS and OS). Signal to noise ratio within each ROI was assessed by calculating t-values for the contrast of all stimulation conditions vs. the fixation baseline. Note that the selection of ROIs is orthogonal to the correlation analysis: the correlation uses difference maps IM–OM and IS–OS, whereas the ROIs are defined by the union of IS and OS conditions, and these conditions are balanced in the experimental design (Kriegeskorte et al., 2009). However, to confirm that a selection bias did not influence our analysis, we also defined ROIs using independent data by splitting each subject's functional data in odd and even runs, using one half to select the ROIs and the other to perform the correlation analysis (and vice versa). The independently defined ROIs overlapped by 68.4% of voxels with ROIs based on the complete data set; and correlation scores did not statistically differ between ROIs defined based on functional data from the same or different runs (paired t-test, t(9) = 0.28, p = 0.786).

We verified that the observed correlations were specific to ROIs in visual cortex by performing the same correlation analysis for randomly selected voxels and contiguous groups of voxels from all areas of the brain. We repeated the correlation analysis for 1000 sets of random voxels of the same size as the original ROIs, picked (with replacement) from all cortical grey matter areas covered by our scan volume. We also selected 1000 contiguous sets of voxels by growing spherical ROIs from randomly selected seed voxels within grey matter until the same number of voxels was reached. Correlation scores for these random sets of voxels form null distributions to test the spatial specificity of the correlation effect between IM-OM and IS-OS difference maps.

To further assess the statistical significance of correlation scores we employed a permutation test: We shuffled the condition labels of IM and OM conditions in each run 1000 times, refitted the GLM, calculated the same difference maps and performed the same correlation analysis as described above. The distribution of the resulting z’ scores represents the null hypothesis that there is no correlation between the difference maps, without making any assumptions about the underlying distribution. The proportion of shuffled samples leading to higher z’ scores than those obtained for the real, unshuffled labels represents a p value of committing a Type I statistical error.

To assess statistical significance at the group level, we used the following approach: We wanted to assess whether the z’ score for a given area in each participant is reliably larger than it would be under the null hypothesis. For each participant we randomly selected one of the shuffled sample z’ scores (above), subtracted it from the unshuffled z’ score, then calculated the mean of this difference across participants, and repeated this procedure 1000 times. The resulting distribution's portion that is smaller than zero represents a p value for the hypothesis that the z’ score is larger than expected under the null hypothesis in the group.

An additional analysis used a Support Vector Machine (Chang and Lin, 2011) to classify patterns of BOLD activity in area MT+ as stemming from either IS or OS conditions (and separately, IM or OM conditions). Classification was performed on beta weights from a GLM that had one predictor for each block in the stimulus sequence from all 6 runs. In a feature selection step, a subset of voxels (~10-15%) with maximal difference in mean activation between IS and OS (or IM and OM) was selected from the whole of MT+ for the classification procedure. This selection of voxels, and training of the SVM, was done on a different subset of the timecourse data than the evaluation of classification performance, and cross-validated 200 times for different randomly selected sets of training and test data. Statistical significance of classification performance was assessed by a permutation test, randomly shuffling block condition labels 1200 times and repeating the same analysis on shuffled labels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Parts of this work were presented at the European Conference on Visual Perception (ECVP) and the Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience (SfN) in 2009. The authors would like to thank E. Sheykhani and N. Wurnitsch for help with data collection and analysis. This research was supported by grant number EY018216 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amano K, Wandell BA, Dumoulin SO. Visual field maps, population receptive field sizes, and visual field coverage in the human MT+ complex. J. Neurophysiol. 2009;102:2704–2718. doi: 10.1152/jn.00102.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Au RKC, Ono F, Watanabe K. Time Dilation Induced by Object Motion is Based on Spatiotopic but not Retinotopic Positions. Front. Psychol. 2012;3:58. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry MJ, Brivanlou IH, Jordan TA, Meister M. Anticipation of moving stimuli by the retina. Nature. 1999;398:334–338. doi: 10.1038/18678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brainard DH. The Psychophysics Toolbox. Spat. Vis. 1997;10:433–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C-C, Lin C-J. LIBSVM : a library for support vector machines. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology. 2011;2:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Crespi S, Biagi L, d'Avossa G, Burr DC, Tosetti M, Morrone MC. Spatiotopic Coding of BOLD Signal in Human Visual Cortex Depends on Spatial Attention. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e21661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d'Avossa G, Tosetti M, Crespi S, Biagi L, Burr DC, Morrone MC. Spatiotopic selectivity of BOLD responses to visual motion in human area MT. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10:249–255. doi: 10.1038/nn1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Valois RL, De Valois KK. Vernier acuity with stationary moving gabors. Vision Res. 1991;31:1619–1626. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(91)90138-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dukelow SP, DeSouza JF, Culham JC, van den Berg AV, Menon RS, Vilis T. Distinguishing subregions of the human MT+ complex using visual fields and pursuit eye movements. J. Neurophysiol. 2001;86:1991–2000. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.86.4.1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagleman DM, Sejnowski TJ. Motion signals bias localization judgments: A unified explanation for the flash-lag, flash-drag, flash-jump, and Frohlich illusions. J. Vis. 2007;7(4):3, 1–12. doi: 10.1167/7.4.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer J, Spotswood N, Whitney D. The emergence of perceived position in the visual system. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2011;23:119–136. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2010.21417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich FW. Über die Messung der Empfindungszeit. Zeitschrift für Sinnesphysiologie. 1923;54:58–78. [Google Scholar]

- Fu YX, Shen Y, Gao H, Dan Y. Asymmetry in visual cortical circuits underlying motion-induced perceptual mislocalization. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:2165–2171. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5145-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner JL, Merriam EP, Movshon JA, Heeger DJ. Maps of visual space in human occipital cortex are retinotopic, not spatiotopic. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:3988–3999. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5476-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gattass R, Gross CG. Visual topography of striate projection zone (MT) in posterior superior temporal sulcus of the macaque. J. Neurophysiol. 1981;46:621–638. doi: 10.1152/jn.1981.46.3.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golomb JD, Kanwisher N. Higher Level Visual Cortex Represents Retinotopic, Not Spatiotopic, Object Location. Cereb. Cortex. 2012;22:2794–2810. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann TS, Bremmer F, Albright TD, Krekelberg B. Receptive field positions in area MT during slow eye movements. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:10437–10444. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5590-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haxby JV, Gobbini MI, Furey ML, Ishai A, Schouten JL, Pietrini P. Distributed and overlapping representations of faces and objects in ventral temporal cortex. Science. 2001;293:2425–2430. doi: 10.1126/science.1063736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huk AC, Dougherty RF, Heeger DJ. Retinotopy and functional subdivision of human areas MT and MST. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:7195–7205. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-16-07195.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolster H, Peeters R, Orban GA. The retinotopic organization of the human middle temporal area MT/V5 and its cortical neighbors. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:9801–9820. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2069-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosovicheva AA, Maus GW, Anstis S, Cavanagh P, Tse PU, Whitney D. The motion-induced shift in the perceived location of a grating also shifts its aftereffect. J. Vis. 2012;12(8):7, 1–14. doi: 10.1167/12.8.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krekelberg B, Lappe M. Neuronal latencies and the position of moving objects. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:335–339. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01795-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegeskorte N, Simmons WK, Bellgowan PSF, Baker CI. Circular analysis in systems neuroscience: the dangers of double dipping. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:535–540. doi: 10.1038/nn.2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis NK. The underpinnings of the BOLD functional magnetic resonance imaging signal. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:3963–3971. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-03963.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maus GW, Weigelt S, Nijhawan R, Muckli L. Does area V3A predict positions of moving objects? Front. Psychol. 2010;1:186. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maus GW, Ward J, Nijhawan R, Whitney D. The Perceived Position of Moving Objects: Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation of Area MT+ Reduces the Flash-Lag Effect. Cereb. Cortex. 2013;23:241–247. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw PV, Walsh V, Barrett BT. Motion-sensitive neurones in V5/MT modulate perceived spatial position. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:1090–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcher D, Morrone MC. Spatiotopic temporal integration of visual motion across saccadic eye movements. Nat. Neurosci. 2003;6:877–881. doi: 10.1038/nn1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris AP, Liu CC, Cropper SJ, Forte JD, Krekelberg B, Mattingley JB. Summation of visual motion across eye movements reflects a nonspatial decision mechanism. J. Neurosci. 2010;30:9821–9830. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1705-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhawan R. Motion extrapolation in catching. Nature. 1994;370:256–257. doi: 10.1038/370256b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhawan R. Visual prediction: Psychophysics and neurophysiology of compensation for time delays. Behav. Brain Sci. 2008;31:197–239. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X08003804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong WS, Bisley JW. A lack of anticipatory remapping of retinotopic receptive fields in the middle temporal area. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:10432–10436. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5589-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong WS, Hooshvar N, Zhang M, Bisley JW. Psychophysical evidence for spatiotopic processing in area MT in a short-term memory for motion task. J. Neurophysiol. 2009;102:2435–2440. doi: 10.1152/jn.00684.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelli DG. The VideoToolbox software for visual psychophysics: transforming numbers into movies. Spat. Vis. 1997;10:437–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran VS, Anstis SM. Illusory displacement of equiluminous kinetic edges. Perception. 1990;19:611–616. doi: 10.1068/p190611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saijo N, Murakami I, Nishida S.y., Gomi H. Large-field visual motion directly induces an involuntary rapid manual following response. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:4941–4951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4143-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz G, Taylor S, Fisher C, Harris R, Berry MJ. Synchronized Firing among Retinal Ganglion Cells Signals Motion Reversal. Neuron. 2007;55:958–969. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg KA, Fallah M, Reynolds JH. A motion-dependent distortion of retinotopy in area V4. Neuron. 2006;49:447–457. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-Planar Stereotaxic Atlas of the Human Brain. G. Thieme; Stuttgart: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Tse PU, Whitney D, Anstis S, Cavanagh P. Voluntary attention modulates motion-induced mislocalization. J. Vis. 2011;11(3):12, 1–6. doi: 10.1167/11.3.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandell BA, Dumoulin SO, Brewer AA. Visual field maps in human cortex. Neuron. 2007;56:366–383. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney D. The influence of visual motion on perceived position. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2002;6:211–216. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(02)01887-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney D. Visuomotor extrapolation. Behav. Brain Sci. 2008;31:220–221. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney D, Cavanagh P. Motion distorts visual space: shifting the perceived position of remote stationary objects. Nat. Neurosci. 2000;3:954–959. doi: 10.1038/78878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney D, Ellison A, Rice NJ, Arnold D, Goodale M, Walsh V, Milner D. Visually Guided Reaching Depends on Motion Area MT+. Cereb. Cortex. 2007;17:2644–2649. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney D, Murakami I, Gomi H. The utility of visual motion for goal-directed reaching. In: Nijhawan R, Khurana B, editors. Space and Time in Perception and Action. Cambride University Press; Cambridge: 2010. pp. 121–145. [Google Scholar]

- Whitney D, Westwood DA, Goodale MA. The influence of visual motion on fast reaching movements to a stationary object. Nature. 2003;423:869–873. doi: 10.1038/nature01693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann FA, Hill NJ. The psychometric function: I. Fitting, sampling, and goodness of fit. Percept. Psychophys. 2001a;63:1293–1313. doi: 10.3758/bf03194544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann FA, Hill NJ. The psychometric function: II. Bootstrap-based confidence intervals and sampling. Percept. Psychophys. 2001b;63:1314–1329. doi: 10.3758/bf03194545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womelsdorf T, Anton-Erxleben K, Pieper F, Treue S. Dynamic shifts of visual receptive fields in cortical area MT by spatial attention. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9:1156–1160. doi: 10.1038/nn1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Womelsdorf T, Anton-Erxleben K, Treue S. Receptive field shift and shrinkage in macaque middle temporal area through attentional gain modulation. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:8934–8944. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4030-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann E, Morrone MC, Burr D. Visual motion distorts visual and motor space. J. Vis. 2012;12(2):10, 1–8. doi: 10.1167/12.2.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.