Abstract

Objective

The detailed assessment of soft tissues over bony prominences and identification of methods of predicting pressure sores would improve the quality of care for patients with spinal cord injury (SCI). Comparing skin thicknesses on bony prominences in patients with SCI to those in healthy individuals will represent, to our knowledge, the first study aimed at determining whether differences in skin thicknesses between these groups can be detected by ultrasound.

Design

In both patients and controls, skin thicknesses on the sites at risk for pressure ulcers – sacrum, greater trochanter, and ischium – were evaluated using high-frequency ultrasound. The waist was also evaluated by the same method for control as it was considered to be a pressure-free region.

Participants

Thirty-two patients with complete thoracic SCI and 34 able-bodied individuals.

Results

The skin was significantly thinner over the sacrum and ischial tuberosity in individuals with SCI compared with healthy individuals. No significant differences were observed in skin thicknesses over the greater trochanter or the waist between the two groups.

Conclusions

Protecting skin integrity in patients with paraplegia is challenging due to many contributing factors, such as prolonged pressure, frictional/shearing forces, and poor nutrition. Thinning of the skin can increase the risk of soft tissue damage, leading to pressure ulcers. The significant differences in skin thickness at the sacrum and ischium provide the basis for establishing the early signs of pressure damage. Measuring skin thickness by ultrasound is a reliable non-invasive method that could be a promising tool for predicting pressure ulcers.

Keywords: Skin thickness, Pressure ulcers, Ultrasonography, Spinal cord injuries, Paraplegia, Prevention, Muscle thickness, Rehabilitation

Introduction

In recent years, ultrasound has gained significant importance for visualizing the inside of joints, tendons, muscles, bursae, and nerves. The skin and subcutaneous tissues are other interesting targets of ultrasound.1 Increased skin thickness in patients with systemic sclerosis and in patients with psoriasis has been assessed and quantitated with ultrasound in dermatological studies.2,3

In addition to the importance of skin thickness, the skin and soft tissues over bony prominences has been a subject of concern in patients with spinal cord injury (SCI). Pressure sores, a frustrating problem affecting wheelchair users, are caused by both external factors such as elevated soft tissue strains and stresses over a critical prolonged period of time as well as internal factors like malnutrition, dehydration, and anemia.4,5 Recently, it has been shown that due to muscle atrophy in individuals with SCI, muscle thickness over bony prominences such as the ischial tuberosity is less than that in healthy individuals as determined by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans.6 It has also been stated that the decreased volume of muscles underlying the bony prominences in individuals with SCI increases vulnerability to pressure ulcers.7 Recent studies using MR images have examined deep tissue deformations and physiological characteristics of the skin, subcutaneous fat and muscle in weight-bearing and supine positions.8,9 However, there have been no controlled studies comparing differences in skin thickness over bony prominences between patients with SCI and control subjects using ultrasonographic measurements. The aim of this study was to evaluate the differences in the thickness of the skin overlying the greater trochanter, ischial tuberosity, and sacrum between individuals with SCI and volunteers without SCI.

Materials and methods

Thirty-two consecutive chronic wheelchair users with SCI and 34 healthy subjects participated in this study. The inclusion criteria for this study were complete thoracic paraplegic individuals with no previous pressure sores and no non-blanching erythema at the time of the study. Demographic data collected included gender, age, level of injury, duration since injury, weight, and height. Patients were questioned regarding hours of daily wheelchair usage and frequency of push-up motion. Persons included in this study were at least 18 years old with traumatic SCI at the thoracic level due to an injury occurring >6 months before the beginning of the study, and they had used a wheelchair for mobility >3 months before the beginning of the study.

Albumin and hemoglobin levels were measured in the patients with SCI to determine whether those indices of nutrition and anemia might be correlated with skin thickness in our cohort.5

We performed ultrasonography by using a linear array probe (7–12 MHz Logiq P5; GE Medical Systems, Wisconsin, USA). To reduce inter-operator error, all measurements were collected by the same physiatrist trained in neuromuscular ultrasound. This physiatrist has used ultrasound for the last 3 years and had 11 years of experience in the management of patients with SCI. The ultrasound room is adequate for the mobilization of the patient and the device with adjustable lighting from bright to dark. All ultrasonic measurements were made ensuring the axis of the transducer was perpendicular to the skin to maximize specular reflection at the skin and subcutaneous tissue interface, so that the most accurate thicknesses was obtained (Fig. 1).

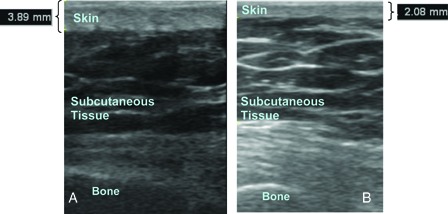

Figure 1.

Skin thickness of (A) a control subject over the ischium, and (B) a patient over the ischium.

Slightest transducer force on the skin was applied through the probe to ensure the transducer rested on the thick layer of gel to avoid affecting the skin thickness. The field depth was 4.5 cm and the focus zone was 1.0 cm. The full skin thickness (epidermis and dermis) from the anterior echogenic border of the epidermis to the posterior echogenic border of the dermis was measured in B-mode. Because the cortical surface of the bone is highly reflective on ultrasound, it could be visualized as a well-defined hyperechoic continuous line in all three measurements10 (Fig. 2). Ultrasonic images were taken three times at each body site in each subject and mean results were calculated. All images were stored in the hard-drive of the ultrasound machine for analyses. After informed consent was taken, the patients were requested to lie prone on the couch. The thickness of the skin at the greater trochanter, ischial tuberosity, and sacrum was measured in the transverse plane. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the waist just at the lateral side of the umbilicus was carried out at the same time. The measurement of the waist was taken as a reference measurement to confirm whether the skin thickness of the two groups was similar at pressure-free areas.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram and ultrasonographic image of skin thickness measurements over the sacrum.

Statistical analyses

The measurements at each of the points of the skin were compared with corresponding points of the control group using the Student's t-test. Pearson's correlation coefficients were calculated between the skin thickness of the sites and with the laboratory (albumin, hemoglobin) and clinical (time since injury, daily hours of wheelchair usage and frequency of push-up intervals) parameters. In all analyses, a P value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

During a 6-month period, 32 wheelchair users (10 women, 22 men; 21 inpatients, 11 outpatients) with complete thoracic SCI and 34 healthy volunteers without SCI (18 men, 16 women) were consecutively recruited to this study. Only three of the inpatient wheelchair users represented primary hospitalization; the others were secondary hospitalizations for neurogenic bladder and psychological and occupational rehabilitation. None of the inpatient wheelchair users was hospitalized due to pressure ulcers.

The healthy volunteers were mainly employees from different sections of the physical and rehabilitation medicine department. The mean age of the patient group was 31 ± 11.1 years and of the control group was 33.7 ± 11.0 years. The average weight was 67.9 ± 12.9 kg in the patient group and 69.7 ± 10.5 kg in the control group. There was no significant difference in age (P = 0.32) or weight (P = 0.53) between the patients and control subjects (95% confidence interval (CI) for age: (−8.15) – (2.74); for weight: (−7.59) – (3.99)]. The mean time since SCI was 17.6 ± 17.8 (range: 6–72) months. All of the patients were (American Spinal Injury Association Classification) ASIA A, and the neurologic levels of the patients were classified as follows: T4: 7 patients; T5: 2 patients; T7: 3 patients; T8: 4 patients; T9: 2 patients; T10: 7 patients; T11: 4 patients; and T12: 3 patients (Table 1).

Table 1.

The neurologic levels of the patients

| Neurologic levels | n |

|---|---|

| T4 | 7 |

| T5 | 2 |

| T7 | 3 |

| T8 | 4 |

| T9 | 2 |

| T10 | 7 |

| T11 | 4 |

| T12 | 3 |

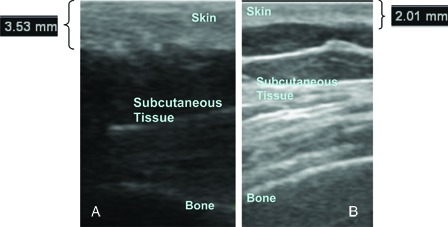

Mean skin thickness of the patient group was 1.8 ± 0.4 mm at the trochanter, 2.1 ± 0.9 mm at the sacrum, 2.2 ± 0.6 mm at the ischium, and 2.3 ± 0.5 mm at the waist. Mean skin thickness of the control group was 1.9 ± 0.5 mm at the trochanter, 3.2 ± 0.5 mm at the sacrum, 2.6 ± 0.5 mm at the ischium, and 2.5 ± 0.6 mm at waist (Figs 1 and 3). The skin was significantly thinner over the sacrum and ischial tuberosity in SCI individuals compared with healthy volunteers. No significant differences were observed in skin thickness over the greater trochanter or waist between the two groups (Table 2).

Figure 3.

(A) Skin thickness of a control subject over the sacrum. (B) Skin thickness of a patient over the sacrum.

Table 2.

Mean skin thickness of patient and control group

| Mean skin thickness (mm) | Patient | Control | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sacrum | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 3.2 ± 0.5 | <0.05 |

| Ischium | 2.2 ± 0.6 | 2.6 ± 0.5 | <0.05 |

| Trochanter | 1.8 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 0.149 |

| Waist | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 0.22 |

One patient was diagnosed with deep tissue injury by ultrasound. The ultrasonographic evaluation of this patient revealed ill-defined layered structure, discontinuous fascia, and heterogeneous hypoechoic area.

There were no significant differences in skin thicknesses between the inpatient and outpatient groups (P = 0.217).

A positive correlation was found between the skin thickness over the trochanter and sacrum in the control group (r = 0.485), but this correlation was not significant in the patient group.

No correlation was noted between skin thickness at any site and the laboratory variables (albumin, hemoglobin), time since injury, hours of wheelchair usage, or time of push-up intervals.

Discussion

Previously published papers have reported significant effects of age, gender, body site, and ethnic origin on skin thickness.11–15 It has also been shown that dermatologic diseases like systemic sclerosis and psoriasis, and also some therapeutic approaches such as radiotherapy, can alter skin thickness.2,3,16 However, to our knowledge, our report is the first to focus on skin thickness over bony prominences among a wheelchair-user population.

The skin of patients with SCI can become thin due to many reasons. Paralysis itself leads to muscle atrophy and loss of collagen, which weakens the skin and reduces its resilience. Impaired sensation increases the vulnerability of the skin to various external factors like heat, cold, friction, shear, and pressure. Furthermore, poor nutrition, hydration, overweight, impaired circulation and oxygenation, impaired cognition, substance abuse, depression, age, undesired weight loss, incontinence, diabetes mellitus, anemia, smoking, corticosteroids therapy, previous ulcers or surgical wounds, and structural deformities of the spinal column all lead to increased risk for skin breakdown through various mechanisms.17–21

The results of this study indicate that skin thickness was decreased at sites under pressure, such as the sacrum and ischial tuberosity. There was no significant difference between the patient and control group regarding skin thickness at relatively pressure-free areas like the waist and greater trochanter. In addition, the observed skin thickness in our study at the waist in both groups was in accordance with the previous literature.15,16 A possible explanation for this result is that the shearing/frictional forces and excessive dryness leading to pressure ulcers could also cause pouring and thinning of the epithelium at sites under prolonged pressure. Thinning of the skin increases the vulnerability of the subcutaneous tissue over bony prominences to pressure ulcers.4 Thus, thinning of the skin could be an early sign of pressure damage. With supporting evidence determined in further studies, the skin thickness on bony prominences could be a follow-up criterion for determining the risk of pressure ulcers in susceptible patient populations.

We did identify a positive correlation between skin thicknesses of the sacrum and trochanter in the control group (rho = 0.485); this finding could not be shown in the patient group.

It seems possible that the correlation in the patient group has been altered due to thinning of the skin over the sacrum as a result of the prolonged pressure. On the other hand, these data must be interpreted with caution because the correlation in the control group was only between the sacrum and trochanter and not other sites. As this could be an incidental result due to the small sample size, this finding should not be generalized.

It has been shown that preoperative serum albumin levels less than 3.0 g/d can increase the risk of pressure ulcers.22 Malnutrition and dehydration, which are commonly seen in people with paraplegia, are possible contributing factors to skin thinning.4 We anticipated that the effect of malnutrition and dehydration would be seen at each site measured in our study. Since there was no significant difference in skin thickness at pressure-free points like the trochanter and waist, malnutrition and dehydration were probably not the main factors leading to these results. Furthermore, we also found no correlation in the patient group between albumin and hemoglobin levels and skin thickness at any site. This finding also seems to support our concept of the effect of pressure in thinning the skin in individuals with SCI. Another important risk factor for developing pressure ulcer is structural deformity due to the SCI. When a structural deformity like prominent ischial and sacrococcygeal segment exists, the patient should be referred for evaluation and possible prophylactic surgery, such as shaving of the bone or providing coverage with a muscle flap for pressure ulcers.21

The first step in the prevention of pressure ulcers is educating patients to assume responsibility for their own skin care. Prevention of the mechanical injury like friction and shearing forces during repositioning and transfers, keeping the skin clean and dry, and consuming a healthy diet should be mentioned. Frequent repositioning and utilization of a pressure-relieving wheelchair cushion or pressure-relieving bed mattress should be advised. In this study, we demonstrated ultrasound to be an objective means of assessing skin thickness in patients with SCI. Skin thickness measured with ultrasonic imaging proved to be a reliable quantitative and non-invasive measure to follow the skin status. This quantitative measurement would alert both the clinicians and patients to the possibility of pressure ulcer development. Thus, this finding has important implications for developing protective care to prevent pressure ulcers. In the coming years, ultrasonographic skin follow-up could be incorporated into the clinical setting by utilizing the existent handheld devices at the bedside.

Although MRI remains the widely accepted standard reference imaging technique for a wide range of disorders, high-resolution ultrasonography is an important complementary, and sometimes alternative, technique.23 A previous study showed that skin thickness measurements with MRI scans had the lowest inter-rater reliability in comparison with the soft tissues like fat and muscle. The authors concluded that this was likely because the skin is the thinnest of the three layers.8 It is known that high-frequency sonography can visualize tiny measurements like skin thickness that simply cannot be shown by standard MRI scans.23

High-resolution ultrasound also has great advantages for the diagnostic evaluation of deep tissue injury. Ultrasound showing damaged reticular dermis and subcutaneous tissue under intact epidermis is one of the proposed diagnostic evaluations for deep tissue injury. Among the 32 patients with SCI, only one patient was diagnosed as deep tissue injury with ill-defined layered structure and a heterogeneous hypoechoic area in ultrasonographic scans.

Limitations

A limitation of this study is that the numbers of patients and controls were relatively small. However, empirical findings in this study provide a new understanding of the alterations of the intact skin in individuals with SCI. This research can serve as a base for future studies to determine whether the significant differences in skin thickness between the sacrum and ischium may increase vulnerability to pressure ulcers. We also emphasize the predictive role of ultrasonography in the early diagnosis and detection of pressure ulcers by providing a means of monitoring skin thickness on bony prominences.

Another possible limitation of this study could be that the skin thickness has been measured by a physician aware of the neurological status of the participants. It would be interesting to assess the measurements of skin thickness in a blinded study.

Conclusion

The significant differences in skin thickness at the sacrum and ischium between the patient and control groups provide the basis for an effect of prolonged pressure on ulcer development. We believe ultrasonography has merit as a predictive tool for pressure-related skin damage; this should be corroborated with further studies. This study provides clinicians with an approach to monitoring the skin changes in patients with SCI as a means of early detection of pressure-related changes.

References

- 1.Grassi W, Cervini C. Ultrasonography in rheumatology: an evolving technique. Ann Rheum Dis 1998;57(5):268–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ihn H, Shimozuma M, Fujimoto M, Sato S, Kikuchi K, Igarashi A, et al. Ultrasound measurement of skin thickness in systemic sclerosis. Br J Rheumatol 1995;34(6):535–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hermann RC, Ellis CN, Fitting DW, Ho VC, Voorhees JJ. Measurement of epidermal thickness in normal skin and psoriasis with high-frequency ultrasound. Skin Pharmacol 1988;1(2):128–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dealey C. Skin care and pressure ulcers. Adv Skin Wound Care 2009;22(9):421–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bansal C, Scott R, Stewart D, Cockerell CJ. Decubitus ulcers: a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44(10):805–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linder-Ganz E, Shabshin N, Itzchak Y, Yizhar Z, Siev-Ner I, Gefen A. Strains and stresses in sub-dermal tissues of the buttocks are greater in paraplegics than in healthy during sitting. J Biomech 2008;41(3):567–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Linder-Ganz E, Gefen A. Stress analyses coupled with damage laws to determine biomechanical risk factors for deep tissue injury during sitting. J Biomech Eng 2009;131(1):011003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Makhsous M, Lin F, Cichowski A, Cheng I, Fasanati C, Grant T, et al. Use of MRI images to measure tissue thickness over the ischial tuberosity at different hip flexion. Clin Anat 2011;24(5):638–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffmann K, Stücker M, Dirschka T, Görtz S, El-Gammal S, Dirting K. Twenty MHz B-scan sonography for visualization and skin thickness measurement of human skin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1994;3(3):302–13 [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Neill J. Introduction to musculoskeletal ultrasound. In: O'Neill J, (ed.) Musculoskeletal ultrasound anatomy and technique. New York: Springer; 2008. p. 13 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seidenari S, Pagnomi A, Di Nardo A, Giannetti A. Echographic evaluation with image analysis of normal skin: variations according to age and sex. Skin Pharmacol 1994;7(4):201–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rigal JD, Escoffier C, Querleux B, Faivre B, Agache P, Leveques JL. Assessment of aging of human skin by in vivo ultrasonic imaging. J Invest Dermatol 1989;93(5):621–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fornage B, McGavran MH, Duvic M, Waldron ChA. Imaging of the skin with 20 MHz US. Radiology 1993;189(1):69–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laurent A, Mistretta F, Bottigioli D, Dahel K, Goujon C, Nicolas JF, et al. Echographic measurement of skin thickness in adults by high frequency ultrasound to assess the appropriate microneedle length for intradermal delivery of vaccines. Vaccine 2007;25(34):6423–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lasagni C, Seidenari S. Echographic assessment of age dependent variations of skin thickness: a study on 162 subjects. Skin Res Technol 1995;1(2):81–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong S, Kaur A, Back M, Lee KM, Baggarley S, Lu JJ. An ultrasonographic evaluation of skin thickness in breast cancer patients after postmastectomy radiation therapy. Radiat Oncol 2011;6:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jackson J, Carlson M, Rubayi S, Scott MD, Atkins MS, Blanche EI, et al. Qualitative study of principles pertaining to lifestyle and pressure ulcer risk in adults with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil 2010;32(7):567–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caliri MH. Spinal cord injury and pressure ulcers. Nurs Clin North Am. 2005;40(2):337–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dean J. Skin health: prevention and treatment of skin breakdown. Transverse Myelitis Assoc J 2011;5:26–32 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Butler CT. Pediatric skin care: guidelines for assessment, prevention, and treatment. Pediatr Nurs. 2006;32(5):443–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rhim B, Harkless L. Prevention: can we stop problems before they arise? Semin Vasc Surg 2012;25(2):122–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Versluysen M. How elderly patients with femoral fracture develop pressure sores in the hospital. Br Med J 1986;17;292(6531):1311–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nazarian LN. The top 10 reasons musculoskeletal sonography is an important complementary or alternative technique to MRI. Am J Roentgenol 2008;190(6):1621–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]