Abstract

Background

Adults with chronic medical conditions are more likely to report unmet health care needs. Whether unmet health care needs are associated with an increased risk of adverse health outcomes is unclear.

Methods

Adults with at least one self-reported chronic condition (arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, hypertension, mood disorder, stroke) from the 2001 and 2003 cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey were linked to national hospitalization data. Participants were followed from the date of their survey until March 31, 2005, for the primary outcomes of all-cause and cause-specific admission to hospital. Secondary outcomes included length of stay, 30-day and 1-year all-cause readmission to hospital, and in-hospital death. Negative binomial regression models were used to estimate the association between unmet health care needs, admission to hospital, and length of stay, with adjustment for socio-demographic variables, health behaviours, and health status. Logistic regression was used to estimate the association between unmet needs, readmission, and in-hospital death. Further analyses were conducted by type of unmet need.

Results

Of the 51 932 adults with self-reported chronic disease, 15.5% reported an unmet health care need. Participants with unmet health care needs had a risk of all-cause admission to hospital similar to that of patients with no unmet needs (adjusted rate ratio [RR] 1.04, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.94–1.15). When stratified by type of need, participants who reported issues of limited resource availability had a slightly higher risk of hospital admission (RR 1.18, 95% CI 1.09–1.28). There was no association between unmet needs and length of stay, readmission, or in-hospital death.

Interpretation

Overall, unmet health care needs were not associated with an increased risk of admission to hospital among those with chronic conditions. However, certain types of unmet needs may be associated with higher or lower risk. Whether unmet needs are associated with other measures of resource use remains to be determined.

Approximately 1 in 3 Canadians have one or more chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, arthritis, or heart disease,1-4 and the direct cost associated with management of these conditions in Canada exceeds $40 billion per year.5 Consequently, improving care for patients with chronic disease has become a major focus in health services research and public health policy.6-9 However, despite multidisciplinary care programs, many Canadians do not receive adequate care for management of their chronic medical conditions.10-12 As such, patients with chronic medical conditions, particularly those with multiple conditions, are more likely to report a perceived unmet health care need, a commonly used indicator of inadequate access to care.13

A perceived unmet health care need is often defined as the difference between services judged necessary to deal effectively with a health problem and services actually received.14 It is conceivable that an unmet need may result in delays in receiving medical attention and, in turn, worse health outcomes.14 If so, then determining the association between unmet health care needs and adverse outcomes is important from the standpoint of health services delivery, as recognition and elimination of potentially modifiable barriers to care may improve health outcomes. However, the evidence relating unmet needs to health care utilization and health outcomes is limited and inconsistent.

Some previous work has shown that unmet needs are associated with higher rates of emergency department visits,15,16 whereas other studies have found equivocal changes in rates of hospital admission and visits to general physicians within the general population.14 Studies employing other commonly used measures of inadequate access to care have found that patients who reported a delay in receiving health care or difficulties in accessing medical services had higher rates of hospital admission and longer lengths of stay,17,18 but other studies have shown no differences in adverse outcomes, including mortality and functional decline.19 These discrepant results may be due to differences in study populations, issues of recall bias, and the use of self-reported measures of health care utilization. Few studies have addressed the effect of unmet needs and outcomes in a high-risk population of patients with chronic disease. Furthermore, the majority of studies to date could not determine if there were differential effects of the type of unmet need on health outcomes.

To address these limitations, we used Canadian population-based data to determine the association between unmet health care needs and risk of admission to hospital among adults with chronic disease. We also sought to determine if unmet health care needs were associated with features of the admission, including length of stay, readmission, and in-hospital death. We hypothesized that, for patients with chronic disease, the presence of a perceived unmet need would result in a higher risk of these outcomes than would be the case in the absence of unmet needs.

Methods

Study population

We obtained data from the 2001 and 2003 cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) with linkage to the national hospitalization file (the Health Person-Oriented Information database) from April 1, 1997, to March 31, 2005. The CCHS is a national survey conducted by Statistics Canada that provides self-reported estimates of health determinants, health status, and health care utilization at the health region level. The target population of the CCHS is household residents aged 12 years and older in the 10 provinces and 3 territories, excluding those living on First Nations reserves or Crown land, full-time members of the Canadian Forces, institutional residents, and some residents of remote areas of Canada.20 The national hospitalization file captures administrative, clinical, and demographic information on hospital stays and provides detailed discharge statistics from Canadian health care facilities, including the dates of admission and discharge, the length of stay, and in-hospital death, as well as diagnostic and procedure codes for each patient. The file includes discharge data received from acute care facilities and selected chronic care and rehabilitation facilities across Canadian provinces except Quebec.21 Within the hospitalization file, diagnostic and procedure codes were based on International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 9th revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) coding until 2001/2002, after which coding from the 10th revision (ICD-10) was implemented.

Survey and hospitalization data were linked at the individual level using an established probabilistic linkage methodology based on unique identifying information, including health insurance number, postal code, date of birth, and sex.22 Linkage was conducted for all CCHS respondents living outside Quebec who provided consent to link their survey data to other sources of health information. Within this linked data source, we identified adults (18 years or older) with at least one self-reported chronic medical condition (specifically arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD] or emphysema, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, hypertension, mood disorders, or stroke) as defined within the CCHS. The Health Council of Canada has recognized these 7 chronic conditions as those with the highest prevalence or the greatest impact on health care utilization.2,3

Perceived unmet health care needs

The exposure of interest was self-reported unmet health care needs identified within the CCHS. Each respondent was asked, “During the past 12 months, was there ever a time when you felt you needed health care but didn’t receive it?” If a respondent answered “yes” to this initial question, additional information was prompted with a follow-up question: “Thinking of the most recent time, why didn’t you get care?” Reasons for an unmet need were classified into 4 categories (accessibility, availability, acceptability, or personal choice), modified from a classification system developed by Chen and Hou.23 These categories were established to separate personal reasons for unmet needs from reasons related to the health care system and to further identify issues related to an individual’s assessment or evaluation of the system (i.e., acceptability) from those related to personal circumstances and unrelated to the health care system (i.e., choice) (Appendix A).

Outcomes

The primary outcomes of interest were all-cause and cause-specific hospital admissions identified within the hospitalization file. The study period for each respondent was defined by date of participation in the CCHS, with follow-up to March 31, 2005 (the most recent date for which hospitalization data were available). For all-cause hospitalization, we assessed the number (count) of hospital admissions, excluding pregnancy-related events. Given that a number of the chronic conditions used to define our study cohort commonly occur together and are associated with vascular-related morbidity,24-26 cause-specific admission for acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and stroke were identified using prespecified ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 codes within the most responsible diagnosis field (Appendix B). Secondary outcomes were in-hospital length of stay (defined as the count of in-hospital days for all admissions following participation in the CCHS survey), 30-day and 1-year all-cause readmission to hospital (identified between the first and second hospital admission after participation in the CCHS), and in-hospital death during any admission.

Other variables of interest

Socio-demographic variables and health behaviours were based on the Behavioral Model of Health Services Use proposed by Andersen,27 a framework to understand determinants affecting health services use and patient satisfaction. The framework includes predisposing factors, enabling factors, personal health choices, and health care system and environmental factors. With the components of this framework in mind, we considered the following variables as potential confounders: age, sex, marital status, education, household income, immigration status, residency type (urban or rural), Aboriginal status, presence of a regular family doctor, perceived health status, body mass index (BMI), smoking and drinking status, and level of physical activity (definitions available at The Canadian Community Health Survey).

Statistical analysis

We described respondents’ socio-demographic information and health behaviours using proportions, which were compared across unmet health care need status using χ2 tests. All descriptive statistics were weighted to reflect the Canadian population, using sampling weights provided by Statistics Canada. Given the multistage sampling methodology of the CCHS surveys, we used bootstrapping techniques to obtain estimates of variance and confidence intervals (CIs).

To determine the relationship between unmet health care needs and risk of all-cause hospitalization, we used multivariate zero-inflated negative binomial regression with backward elimination techniques. This regression analysis addresses the excess of zero counts (participants with no admissions), as well as the potential for overdispersion observed within the distribution of hospital events as compared with the Poisson distribution. We identified potential effect modifiers a priori and developed interaction terms for unmet need × age and unmet need × sex. We assessed model fit by the likelihood ratio test. We calculated rate ratios (RRs) for respondents with an unmet health care need compared with those without unmet needs (reference group), with adjustment for socio-demographic variables, health behaviours, health status, and survey cycle (to account for change across time). Age was categorized as 18–44 years, 45–64 years, or 65 years and older. BMI was categorized as obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) or non-obese (< 30 kg/m2). For household income, “missing” was included as a separate category because of the large number of respondents for whom data were missing for this variable. Similar models were developed to determine whether the association between unmet health care need and all-cause hospitalization differed by the type of unmet need reported (accessibility, availability, acceptability, or personal choice).

The association between unmet needs and cause-specific hospitalization for acute myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and stroke among respondents with chronic disease was also assessed. Recognizing that associations with barriers to care and cause-specific hospital outcomes may differ by type of chronic disease, we also performed a sensitivity analysis for participants with self-reported vascular-related chronic conditions (hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, and stroke). We performed a number of additional sensitivity analyses on the primary outcome. First, given the possibility that an unmet health care need might affect patients with chronic disease in a more immediate fashion, we aimed to assess the influence of follow-up time on all-cause hospitalization by limiting study follow-up to 1 year after participation in the CCHS survey. Second, because individuals with multiple chronic conditions are more likely to report an unmet need,13 we performed additional analyses to determine the influence of the number of chronic conditions on all-cause hospitalization.

For the secondary outcomes (length of stay, all-cause readmission to hospital within 30 days or 1 year, and in-hospital death), we limited the cohort to participants with chronic disease who had at least one admission to hospital. To determine the relationship between unmet health care needs and length of stay, we performed multivariate negative binomial regression modelling. We used multivariate logistic regression to model the odds of readmission to hospital and in-hospital death by unmet health care need status. Model development and assessment were similar to those described for the primary outcomes.

For all statistical tests, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted at the Prairie Regional Data Centre in Calgary, Alberta, using STATA 11.0 (Statacorp, College Station, TX). This study was approved by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Calgary and by Statistics Canada.

Results

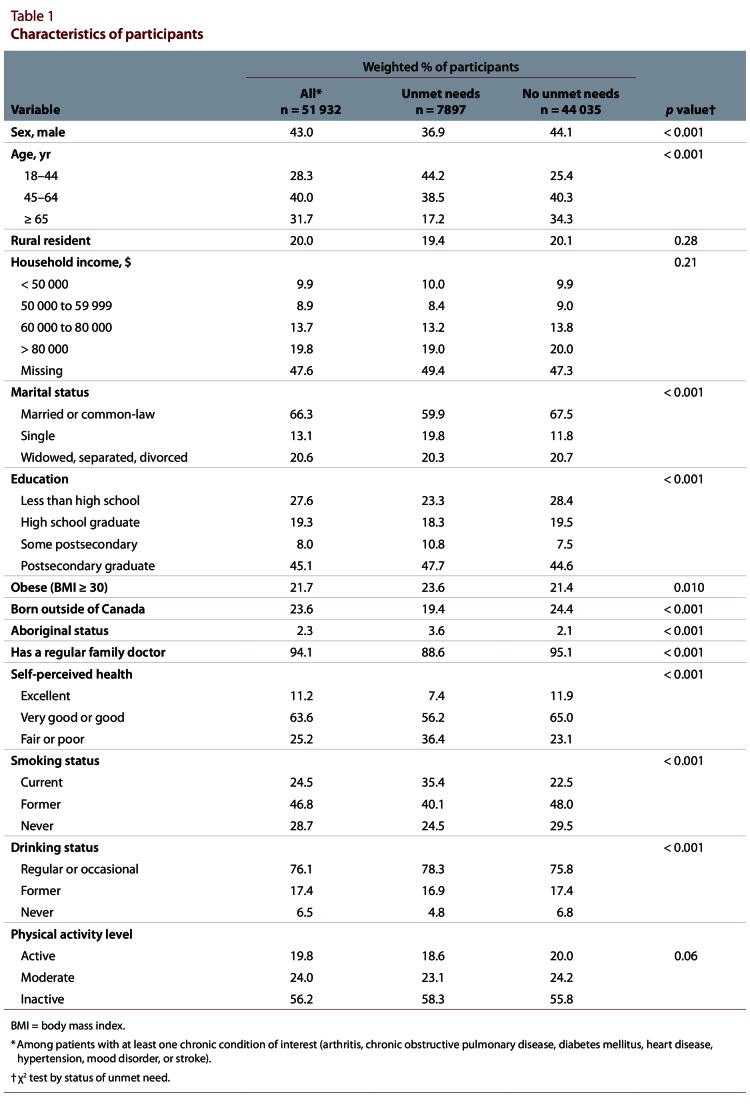

A total of 51 932 adult respondents with at least one chronic medical condition were included in the study cohort, of whom 15.5% reported an unmet need in the previous year. Participants with an unmet need were younger, were more likely to be female, had higher levels of education, and were more likely to be obese relative to those with no reported unmet needs. Furthermore, the proportion of respondents with a regular family doctor was lower among those with a reported unmet need (Table 1). Among the 7897 participants with a reported unmet need, the most commonly reported unmet needs related to availability (50.4%) and personal choice (35.8%). The proportion of participants reporting an unmet need also varied by type and number of chronic conditions present (Appendix C). Specifically, participants with mood disorders were most likely to report an unmet need (25.6%), whereas individuals with hypertension and diabetes were least likely to do so (10.8% and 12.2%, respectively). Generally, the proportion of participants reporting unmet needs increased with the number of chronic conditions. Among respondents with a single chronic condition, 15.3% reported an unmet need. This proportion increased to 17.9% among respondents with 3 or more chronic conditions.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

Association between unmet needs and all-cause admission to hospital

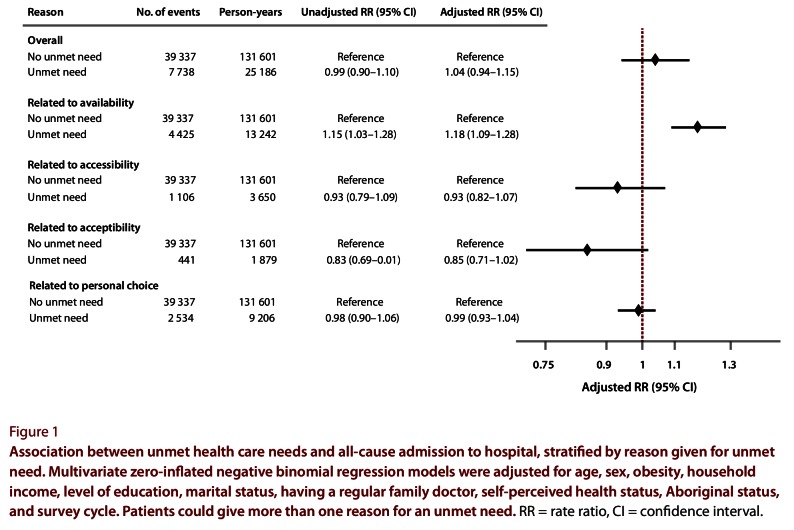

The mean follow-up time for participants was 3.0 years (standard deviation 1.1 years). During the study period, 21 166 participants experienced a total of 47 075 all-cause admissions to hospital. Compared with respondents without unmet needs, there was no greater risk of all-cause hospitalization for respondents with an unmet need (adjusted RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.94–1.15) (Figure 1). There was no evidence of effect modification by age (p = 0.61) or sex (p = 0.12). When the data were stratified by type of unmet need, we found that participants reporting an unmet need related to availability of resources had a slightly greater risk of admission to hospital than those with no unmet needs (adjusted RR 1.18, 95% CI 1.09–1.28). For participants reporting unmet needs related to acceptability, there was no difference in the risk of hospital admission relative to those with no unmet needs (adjusted RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.71–1.02). Participants reporting unmet needs related to availability tended to be older, were more likely to live in rural areas, and had higher levels of education and income than participants reporting other types of unmet need (accessibility, acceptability, and personal choice) (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Association between unmet health care needs and all-cause admission to hospital, stratified by reason given for unmet need.

Association between unmet needs and cause-specific admission to hospital

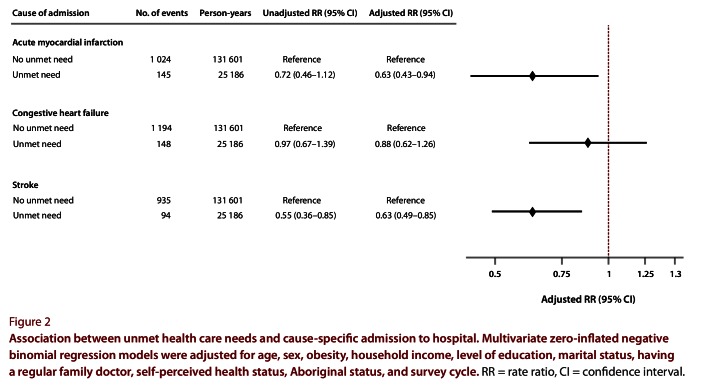

Compared with participants with no unmet needs, participants who had unmet needs were less likely to be admitted to hospital for acute myocardial infarction (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.43–0.94) or stroke (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.49–0.85) (Figure 2). No differences were observed in the risk of admissions related to congestive heart failure (RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.62–1.26).

Figure 2.

Association between unmet health care needs and cause-specific admission to hospital.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses limiting the study cohort to participants with vascular-related chronic conditions (n = 14 618) did not change the observed association between unmet needs and all-cause hospitalization (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.91–1.26). However, the associations between unmet needs and cause-specific admissions were attenuated and became nonsignificant: for acute myocardial infarction, RR 1.05 (95% CI 0.70–1.56); for stroke, RR 0.57 (95% CI 0.32–1.03), and for congestive heart failure, RR 1.20 (95% CI 0.63–2.26). Limiting study follow-up to a 1-year period after participation in the CCHS survey resulted in a similar risk of all-cause hospitalization among participants with and without unmet needs (adjusted RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.81–1.19). Similarly, individual models assessing the association between unmet needs and all-cause hospitalization by number of chronic conditions found no association: for 1 condition, adjusted RR 0.98 (95% CI 0.86–1.12); for 2 conditions, RR 1.18 (95% CI 0.98–1.39); and for 3 or more conditions, RR 0.96 (95% CI 0.84–1.09).

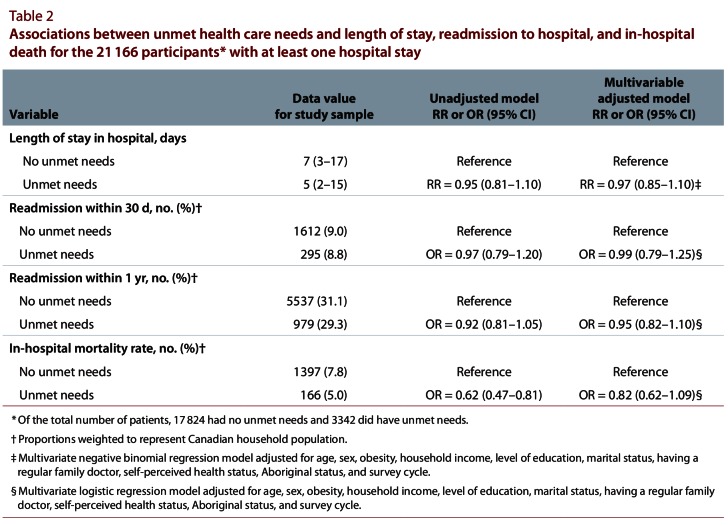

Association between unmet needs and length of stay, readmission, and in-hospital death

Among participants with at least one hospital admission, we found no differences in length of stay between participants with unmet needs and those without such needs (adjusted RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.85–1.10) (Table 2) or in the risk of 30-day or 1-year readmission to hospital (Table 2). Similarly, there was no association between unmet needs and in-hospital death (adjusted odds ratio 0.82, 95% CI 0.62–1.09).

Table 2.

Associations between unmet health care needs and length of stay, readmission to hospital, and in-hospital death for the 21 166 participants* with at least one hospital stay

Interpretation

Using a large population-based survey linked to national hospitalization records, we found no association between perceived unmet health care needs and risk of hospitalization (all-cause or cause-specific) among participants with chronic disease. Only among adults reporting unmet needs related to resource availability was there a slightly increased risk of all-cause hospitalization, relative to those with no unmet needs. Furthermore, there was no association between unmet health care needs and certain features of the hospital admission, including length of stay, subsequent readmission, or in-hospital death.

Previous studies using the CCHS have found that unmet needs are associated with increased use of health care resources, including general physician visits and emergency department visits.14-16 Although few studies have explored the association between unmet needs and hospital admissions specifically, it has been suggested that respondents with unmet needs also have more hospital admissions than those with no unmet needs.14 However, the findings of that study, based on self-reported measures of health care use, were statistically nonsignificant. One strength of our current study was the ability to measure the outcomes of interest within national administrative data, which eliminated concerns about recall bias that may have been present in prior studies.

In relation to other commonly used measures of limited access to care, our findings contrast with previous work suggesting that limited access or delays in seeking care may result in increased risk of hospital admission and longer lengths of stay.17,18 Bindman and colleagues17 explored the association between self-reported access to care and risk of hospital admission in California and reported that individuals with poor perceived access to medical care (according to a 5-point scale that asked respondents how difficult it was for them to get health care) had higher rates of admission to hospital for chronic diseases than those with no access difficulties. Similarly, Weissman and colleagues18 observed that patients who reported a delay in receiving medical attention had hospital stays that were 9% longer compared with patients who reported no delays. Although these results suggest a potential association between limited access to care and hospital-related outcomes, both studies had a cross-sectional design and could not be used to determine if the perceived barriers to care preceded the outcomes of interest. In our study, the prospective design eliminated issues of temporality. A prior study also employing a prospective design found no association between self-reported delays in care and health outcomes. Specifically, Rupper and colleagues19 showed that delays in seeking medical attention did not increase the risk of mortality or functional decline in a population of community-dwelling elderly participants. They concluded that additional work is needed to explore the process of seeking health care and to better understand the current measures of limited access to care that are used in health research.

An interesting finding that warrants further exploration was the differential effect of the type of unmet need and the risk of all-cause hospitalization. We found a small but statistically significant increased risk of all-cause hospitalization among participants with an unmet need related to availability (lengthy wait times and unavailable services) but not for other types of need (related to accessibility, acceptability or personal choice). A prior study suggested a trend toward increased risk of hospitalization for patients with an unmet need related to wait times and limited resource availability, but the results were not statistically significant.14 Although it is difficult to determine the exact mechanism behind this association, we speculate that not receiving timely care may result in additional requirements for care at a later date. Regardless, these findings highlight the need for a disaggregated approach to the study of unmet needs in future studies and suggest that specific types of unmet needs may put patients with chronic disease at greater risk for adverse outcomes.

We found that participants with chronic disease and an unmet health care need were less likely to have cause-specific admissions to hospital for acute myocardial infarction and stroke. This may, in part, be a result of the chronic conditions used to define our study cohort. Reasons for hospital admission may be different between patients with symptomatic chronic conditions (arthritis, COPD, mood disorders) and patients with vascular-related chronic conditions (diabetes, hypertension, heart disease, stroke). Furthermore, this association was attenuated and nonsignificant when we limited our cohort to participants with vascular-related chronic conditions.

Our overall finding of no association between unmet needs and risk of admission to hospital, readmission to hospital, or mortality can be interpreted in a number of ways. First, it may indicate that the Canadian health care system, with universal access, is adequate to meet the needs of individuals with chronic disease. Despite 15.5% of adults with chronic disease reporting an unmet need, these unmet needs did not translate into an increased risk of inpatient hospitalization and related events. Second, patients with unmet needs may be accessing other elements of the health care system to maintain their health status and avoid admission to hospital. Specifically, unmet needs have been associated with increased visits to the emergency department16 and to general practitioners practising in emergency departments as opposed to primary care settings.15 Finally, it is also possible that our current measures of limited access to care are nonspecific and cannot discriminate between those who are and are not at risk for adverse outcomes. The need for future work to better understand the meaning of the term “unmet need” and how patients interpret questions about unmet needs in the setting of health surveys has been emphasized.28

Limitations and strengths

Our results should be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. First, our exposure of interest was obtained from self-reported survey data that were measured at one point in time for each patient. As a result, we could not determine if an unmet need reported at the beginning of the study period for a particular participant was sustained throughout follow-up or represented a short-term need that was later resolved. Although it is possible that our relatively long follow-up period is one reason for the null findings (since the effect of an unmet need might be more immediately realized in this population), the results were similar in our sensitivity analysis in which follow-up was limited to 1 year. Future studies should consider the use of a time-varying covariate to measure the effect of unmet needs over time. However, given the constant need for care among patients with chronic disease, in particular those with multiple chronic conditions, it is likely that a perceived unmet need would be sustained throughout follow-up. Second, our study cohort was also based on self-reported data and may underestimate the true prevalence of chronic disease in the population. The cohort was heterogeneous and included patients with several different chronic conditions. Given that unmet health care needs varied by the type of chronic condition, it is possible that differential associations by disease type would explain the null finding between unmet needs and all-cause hospitalization. Unfortunately, we could not adequately model these associations with our study sample. Third, social and behavioural risk factors such as BMI and smoking status may have changed during the study period. Given that these covariates were also measured at a single point in time, we are unable to determine their influence on our study findings. Furthermore, there is a possibility of residual confounding, as we could not adjust for severity or duration of chronic disease, 2 variables that may affect the potential association in question. We did, however, adjust for self-perceived health status and a number of other relevant covariates using the Behavioral Model of Health Services Use proposed by Andersen27 and feel that any unmeasured variables would have had to be very strong to have influenced our findings. Finally, we did not capture outpatient deaths and were unable to account for this as a potential competing risk in our analysis. However, the number of deaths outside hospitals is likely to be low and similar across categories of unmet need.

Despite these limitations, our study had a number of strengths. Our ability to link national survey data with national hospitalization records offered a unique opportunity to comprehensively assess the effect of unmet health care needs on health care utilization and outcomes in patients with chronic disease. The use of a prospective cohort design also ensured that the defined exposure preceded the outcomes of interest and allowed us to account for differential follow-up times among study participants. Finally, the use of a population-based cohort of adults (at least 18 years of age) with at least one high-impact chronic condition increased the generalizability of the study results. This is particularly important given the growing burden of chronic disease in Canada and abroad.

Conclusions

Our study has provided a national perspective on the association between unmet health care needs and hospital outcomes among adults with chronic medical conditions, indicating that adults with chronic conditions and perceived unmet needs do not experience an increased risk of hospital-specific outcomes. The small increased risk for the subgroup with an unmet need defined by limited resource availability may suggest a high-risk group in which unmet needs result in poor health outcomes. Future work should focus on identifying such groups, as well as exploring other measures of health care utilization that may better reflect the effects of perceived unmet needs.

Biographies

Paul E. Ronksley, MSc, is a PhD candidate in the Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

Claudia Sanmartin, PhD, is a Senior Research Analyst for the Health Analysis Division of Statistics Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. She is also an Assistant Professor in the Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

Hude Quan, MD, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

Pietro Ravani, MD, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the Departments of Medicine and of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

Marcello Tonelli, MD, SM, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta.

Braden Manns, MD, MSc, is an Associate Professor in the Departments of Medicine and of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

Brenda R. Hemmelgarn, MD, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the Departments of Medicine and of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta.

Appendices

Appendix A.

Categorization of types of unmet need

Appendix B.

ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 codes for identifying cause-specific hospitalizations

Appendix C.

Proportion of participants reporting an unmet health care need, by type and number of chronic medical conditions

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Funding source: Paul Ronksley is supported by a Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Hude Quan, Marcello Tonelli, Braden Manns, and Brenda Hemmelgarn are supported by career awards from Alberta Innovates – Health Solutions. Dr. Hemmelgarn is also supported by the Roy and Vi Baay Chair in Kidney Research. The study was supported by a team grant from Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (now Alberta Innovates – Health Solutions). The analyses were based on data collected by Statistics Canada. However, the results and interpretations presented in this paper do not represent the opinions of Statistics Canada.

Paul Ronksley was involved in the conception and design of the study. He was also responsible for drafting the manuscript, conducting the analysis, and interpreting the data. Claudia Sanmartin contributed to conception and design and to interpretation of data, as well as providing intellectual content. Hude Quan, Pietro Ravani, Marcello Tonelli, and Braden Manns contributed to the conception and design of the study and provided interpretation and intellectual content to subsequent drafts of the manuscript. Brenda Hemmelgarn also contributed to the study conception and design, data interpretation, and manuscript revisions. All authors read and approved the final draft. Dr. Hemmelgarn is the study guarantor.

References

- 1.Broemeling Anne-Marie, Watson Diane E, Prebtani Farrah. Population patterns of chronic health conditions, co-morbidity and healthcare use in Canada: implications for policy and practice. Healthc Q. 2008;11(3):70–76. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2008.19859. http://www.longwoods.com/product.php?productid=19859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Why health care renewal matters: learning from Canadians with chronic health conditions. Toronto (ON): Health Council of Canada; 2007. [accessed 2011 Apr. 17]. http://www.healthcouncilcanada.ca/tree/2.20-Outcomes2FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadians’ experience with chronic illness care in Canada: a data supplement to Why health care renewal matters: learning from Canadians with chronic health conditions. Toronto (ON): Health Council of Canada; 2007. [2011 Apr. 17]. http://www.healthcouncilcanada.ca/rpt_det.php?id=144. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manuel Douglas G, Leung Mark, Nguyen Kathy, Tanuseputro Peter, Johansen Helen. Burden of cardiovascular disease in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2003;19(9):997–1004. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=12915926. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mirolla M. The cost of chronic disease in Canada. Ottawa (ON): Chronic Disease Prevention Alliance of Canada; 2004. [2012 Jan. 19]. http://www.gpiatlantic.org/pdf/health/chroniccanada.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed Sara, Gogovor Amede, Kosseim Mylene, Poissant Lise, Riopelle Richard, Simmonds Maureen, Krelenbaum Marilyn, Montague Terrence. Advancing the chronic care road map: a contemporary overview. Healthc Q. 2010;13(3):72–79. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2010.21819. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=20523157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dancer Susan, Courtney Maureen. Improving diabetes patient outcomes: framing research into the chronic care model. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2010 Oct 19;22(11):580–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis R M, Wagner E H, Groves T. Managing chronic disease. BMJ. 1999 Apr 24;318(7191):1090–1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7191.1090. http://www.bmj.com/cgi/doi/10.1136/bmj.318.7191.1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wagner E H. Managed care and chronic illness: health services research needs. Health Serv Res. 1997;32(5):702–714. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/9402910. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canadian Health Care Matters Bulletin 2. Toronto (ON): Health Council of Canada; 2010. [accessed 2011 Jan. 4]. Helping patients help themselves: Are Canadians with chronic conditions getting the support they need to manage their health? http://www.healthcouncilcanada.ca/tree/2.17-AR1_HCC_Jan2010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Disparities in primary health care experiences among Canadians with ambulatory care sensitive conditions. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2012. [accessed 2012 Mar. 30]. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webster Greg, Sullivan-Taylor Patricia, Terner Michael. Opportunities to improve diabetes prevention and care in Canada. Healthc Q. 2011;14(1):18–21. doi: 10.12927/hcq.2011.22152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ronksley Paul Everett, Sanmartin Claudia, Quan Hude, Ravani Pietro, Tonelli Marcello, Manns Braden, Hemmelgarn Brenda R. Association between chronic conditions and perceived unmet health care needs. Open Med. 2012;6(2):48–58. http://www.openmedicine.ca/article/view/483/459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allin Sara, Grignon Michel, Le Grand Julian. Subjective unmet need and utilization of health care services in Canada: What are the equity implications. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(3):465–472. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.10.027. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0277953609007175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCusker Jane, Roberge Danièle, Lévesque Jean-Frédéric, Ciampi Antonio, Vadeboncoeur Alain, Larouche Danielle, Sanche Steven. Emergency department visits and primary care among adults with chronic conditions. Med Care. 2010;48(11):972–980. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181eaf86d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zuckerman Stephen, Shen Yu-Chu. Characteristics of occasional and frequent emergency department users: Do insurance coverage and access to care matter. Med Care. 2004;42(2):176–182. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000108747.51198.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bindman A B, Grumbach K, Osmond D, Komaromy M, Vranizan K, Lurie N, Billings J, Stewart A. Preventable hospitalizations and access to health care. JAMA. 1995 Jul 26;274(4):305–311. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03530040033037. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=7609259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weissman J S, Stern R, Fielding S L, Epstein A M. Delayed access to health care: risk factors, reasons, and consequences. Ann Intern Med. 1991 Feb 15;114(4):325–331. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-4-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rupper Randall W, Konrad Thomas R, Garrett Joanne M, Miller William, Blazer Dan G. Self-reported delay in seeking care has poor validity for predicting adverse outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(12):2104–2109. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52572.x. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=15571551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Béland Y. Canadian community health survey–methodological overview. Health Rep. 2002;13(3):9–14. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/studies-etudes/82-003/archive/2002/6099-eng.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanmartin C, Khan S LHAD Research Team. Hospitalizations for ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSC): the factors that matter. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2011. [accessed 2011 Dec. 17]. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-622-x/82-622-x2011007-eng.pdf. Health Research Working Paper Series. Cat. no. 82-622-X — No. 007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rotermann Michelle. Evaluation of the coverage of linked Canadian Community Health Survey and hospital inpatient records. Health Rep. 2009;20(1):45–51. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-003-x/2009001/article/10773-eng.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Jiajian, Hou Feng. Unmet needs for health care. Health Rep. 2002;13(2):23–34. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/studies-etudes/82-003/archive/2002/6061-eng.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adler A I, Stratton I M, Neil H A, Yudkin J S, Matthews D R, Cull C A, Wright A D, Turner R C, Holman R R. Association of systolic blood pressure with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 36): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321(7258):412–419. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.412. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/10938049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kannel W B, McGee D L. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The Framingham study. JAMA. 1979 May 11;241(19):2035–2038. doi: 10.1001/jama.1979.03290450033020. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=430798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stratton I M, Adler A I, Neil H A, Matthews D R, Manley S E, Cull C A, Hadden D, Turner R C, Holman R R. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321(7258):405–412. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405. http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/10938048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andersen Ronald M. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. doi: 10.2307/2137284. http://www.scholaruniverse.com/ncbi-linkout?id=7738325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson Kathi, Rosenberg Mark W. Accessibility and the Canadian health care system: squaring perceptions and realities. Health Policy. 2004;67(2):137–148. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(03)00101-5. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0168851003001015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]