Abstract

Loss-of-function mutations in the gene coding for perforin (PRF1) markedly reduce the ability of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and natural killer cells to kill target cells, causing immunosuppression and impairing immune regulation. In humans, nearly half of the cases of type 2 familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis are due to bi-allelic PRF1 mutations. The partial inactivation of PRF1 due to mutations that promote protein misfolding or the common hypomorphic allele coding for the A91V substitution have been associated with lymphoid malignancies in childhood and adolescence. To investigate whether PRF1 mutations also predispose adults to cancer, we genotyped 566 individuals diagnosed with melanoma (101), lymphoma (65), colorectal carcinoma (30) or ovarian cancer (370). The frequency of PRF1 genotypes was similar in all disease groups and 424 matched controls, indicating that the PRF1 status is not associated with an increased susceptibility to these malignancies. However, four out of 15 additional individuals diagnosed with melanoma and B-cell lymphoma during their lifetime expressed either PRF1A91V or the rare pathogenic PRF1R28C variant (p = 0.04), and developed melanoma relatively early in life. Both PRF1A91V- and PRF1R28C-expressing lymphocytes exhibited severely impaired but measurable cytotoxic function. Our results suggest that defects in human PRF1 predispose individuals to develop both melanoma and lymphoma. However, these findings require validation in larger patient cohorts.

Keywords: A91V, FHL, dual tumors, lymphoma, melanoma, perforin

Introduction

Perforin (PRF1) is a pore-forming protein that is critical for the function of cytotoxic lymphocytes (CLs), which kill not only transformed cells but also cells harbouring intracellular pathogens.1 CLs span both the innate and adaptive immune compartments, and comprise cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), natural killer (NK) cells, NKT cells and γδ T cells. These cells can secrete PRF1constitutively or in response to a pathogenic (“danger”) signal, and most often do so together with serine proteases (granzymes), which synergize with PRF1 to mediate the death of target cells. PRF1 and granzymes are co-stored in acidic secretory vesicles and—upon the exocytosis of these granules—diffuse across the immune synapse to reach target cells.2

The fact that PRF1 is critical in both humans and mice can be gauged from the spectrum of pathologies associated with its deficiency.2 Targeted Prf1-disruption in mice results in severe immunosuppression, which manifests primarily as an increased susceptibility to multiple viruses and (mostly intracellular) bacteria.3 In addition, Prf1−/− mice succumb more readily to transplanted,4 virus-induced5 and spontaneous malignancies6 than their wild-type (WT) counterparts. Specifically, more than 60% of Prf1-deficient mice develop aggressive B-cell lymphomas beyond the age of 12 mo6 and are more susceptible to sarcomas induced by the chemical carcinogen methylcholanthrene.4 Congenital PRF1 deficiency in humans has been described for the first time relatively recently. Sporadic inactivating mutations of PRF1 are infrequent, with a rate of heterozygosity of 1 in every 150 individuals in outbred populations.7 Accordingly, bi-allelic mutations are rare but still account for around 50% of cases of the autosomal recessive disorder known as type 2 familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (FHL), which affects 1 in 90,000 live births.8

Children affected by type 2 FHL and null for PRF1 activity present in early infancy (< 6 mo of age) with a profound immunoregulatory disorder, the hallmarks of which are pancytopenia, hemophagocytosis in the spleen and bone marrow, intractable fevers, neurological and renal dysfunction and markedly raised levels of circulating cytokines.9 This condition is generally fatal unless the immune system is reconstituted through allogenic stem cell transplantation.10,11 Conversely, in cases in which missense PRF1 mutations allow for (some) residual PRF1 activity, the clinical presentation can be delayed to adolescence or even adulthood, and the manifestations may be atypical.2 Many of these individuals present indeed with hematological cancers, intractable viral infections (in particular by the Epstein–Barr virus) or post-viral syndromes such as the polyneuropathy known as Guillain–Barre syndrome.12

A number of studies have previously examined the genotype of PRF1 in cohorts of patients affected by hematological malignancies to test whether an association would exist between the relatively common allele encoding PRF1A91V (in which the alanine residue at position 91 is substituted by valine) and cancer susceptibility. PRF1A91V heterozygotes comprise 8–9% of healthy Caucasian populations, although far fewer African Americans and Japanese carry this allele.13,14 Surprisingly, it has recently been shown that the A91V substitution, which was previously assumed to be biochemically “conservative” and therefore of little functional importance, causes a severe reduction in PRF1 activity.15 These findings have added some substance to the observation that A91V is “overrepresented” in the few cases of late onset type 2 FHL identified to date, particularly in a homozygous state. A study conducted on a small patient cohort has identified a tentative relationship between A91V and childhood leukemia/lymphoma.16 This association was not confirmed by a subsequent study involving a larger patient cohort, yet A91V turned out to be more common in a subgroup of 24 patients bearing BCR-ABL+ acute lymphoblastic leukemia.13 Appropriately, the authors recommended caution in assigning biological significance to this observation, due to the small sample size.

Here, we performed a retrospective analysis of the incidence of the A91V-coding allele and other PRF1 mutations in adults diagnosed with a variety of hematological or epithelial malignancies and appropriately matched healthy subjects. Although we found no increased prevalence of PRF1A91V, the frequency of PRF1 mutations was elevated in melanoma patients who had also experienced a second malignancy in their lifetime, especially a B-cell lymphoma. Four unrelated patients out of 15 found in this subset inherited either PRF1A91V or a rare PRF1 allele (PRF1R28C), which we demonstrate here to code for a PRF1 variant that has minimal lytic activity, and hence to represent a second but genuinely defective PRF1 allele.

Materials and Methods

Patients and control subjects

Unless otherwise stated, all patients attended either the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre (Peter Mac) or the Oncology Department of Austin and Repatriation Medical Centre, two large tertiary referral centers in Melbourne (Australia). DNA from healthy control subjects was sourced from the Peter Mac Biobank. Ovarian cancer cases and controls were residents of Southampton, UK between 1993 and 1998, as described previously,17 and comprised representative numbers of serous, mucinous, endometrioid, clear cell and undifferentiated adenocarcinomas. All of the controls were white female volunteers or obstetrics outpatients. The control and cancer groups were drawn from the same geographical area and were predominantly Anglo-Saxon. Surgically excised colon carcinomas were collected at Western General Hospital, Melbourne, Australia, between 1993 and 1999. The collection of all bio-specimens and patient data was approved by the respective human ethics committees, and their use in the current study was approved by Peter Mac’s Human Ethics Committee.

Preparation of genomic DNA

Clinical samples were received as whole blood, tumor tissue or (occasionally) pre-purified genomic DNA. For DNA purification, leukocytes or tissue were digested overnight at 55°C in extraction buffer (100 mM Tris pH 8.0, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 200 mM NaCl) containing 10 mg/mL proteinase K. Residual debris were removed by centrifugation and genomic DNA precipitated by adding an equal volume of ice-cold isopropanol. The DNA pellet was washed with 70% ethanol, air-dried and redissolved in sterile water.

High resolution melt (HRM)

HRM was performed in a 2-plex QIAGEN Rotor-Gene Q apparatus (QIAGEN Australia), to detect PRFA91V. The primers used were F653: 5′-GGCCCGCCAGTTGGTGAG-3′ and R638: 5′-CACCCTCTGTGAAAATGCCCTACAG-3′, producing a product of 85 bp, which was analyzed using QIAGEN Rotor-Gene Q software version 2.0.3.

DNA sequencing

PRF1 exons were amplified using the following primers: Exon 2 (1827: 5′-CCCCTGTCTCTGCAGCTC-3′, 1830: 5′-CCCTAGCCCCAGCTCTCA-3′); first portion of Exon 3 (3F: 5′-CCAGTCCTAGTTCTGCCCACTTAC-3′, 1836: 5′-CATGCTTGGATGAAGGTCAC-3′); second portion of Exon 3 (1835: 5′-CCTCCATTAACGACCTGCTG-3′, 3R: 5′-GAACCCCTTCAGTCCAAGCATAC-3′), and then gel purified. The same primers were used for sequencing, based on the ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing (Applied Biosystems).

PRF1 expression and function

WT and mutant PRF1R28C (generated by site-directed mutagenesis18) were expressed in rat basophilic leukemia (RBL) cells or in primary cytotoxic T lymphocytes of Prf1−/− mice that were also transgenic for an ovalbumin-specific T-cell receptor (Prf1−/−.OT-1 mice) and cytotoxicity was assessed as described previously.15

Statistical analyses

The frequency of PRF1 mutations in melanoma patients was compared with healthy control samples using two-tailed Fisher’s exact test. In the case of ovarian cancer, the equivalent comparison was made with a control population with benign ovarian conditions collected in the same geographic area (Southampton, UK).

Results

In order to investigate a possible association between the severely hypomorphic allele PRF1A91V and adult cancer, we genotyped 566 individuals who had been diagnosed with melanoma, lymphoma, colorectal or ovarian cancer. We have previously shown that the A91V substitution, which has a frequency of 8–10% in various Caucasian populations, results in severe PRF1 dysfunction.19 We found that the frequency of PRF1A91V heterozygosity in an independent, healthy, gender-matched control population was 7.6% (9/118), which was not statistically different from the PRF1A91V frequency observed among 30 colorectal cancer (2/30, 6.7%) or ovarian cancer (21/370, 5.7%) patients (Table 1; Table S1). There was no over-representation of PRF1A91V in either of the major histological subtypes of ovarian cancer, mucinous or serous (data not shown). The incidence of PRF1A91V in a further group of women diagnosed with various benign ovarian pathologies was slightly elevated (25/241, 10.4%) in comparison to that of ovarian cancer patients, but this did not reach statistical significance (p < 0.07).

Table 1. Frequency of perforin mutations in melanoma patients.

| Tumor group | Samples, n | A91V, n | Other variants, n | A91V variant, % | Variant (total), % | Fisher’s Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control |

118 |

9 |

0 |

7.6 |

7.6 |

N/A |

| Melanoma |

143 |

14 |

2* |

9.8 |

11.2 |

p = 0.40 |

| Melanoma + lymphoma |

15 |

2 |

2 |

13.3 |

26.7 |

p = 0.04 |

| Melanoma + other | 28 | 3 | 0* | 10.7 | 10.7 | p = 0.71 |

The N252S polymorphism, which has no apparent effect on perforin function in vitro, was found in a third patient but s/he was not included in the statistical calculations.

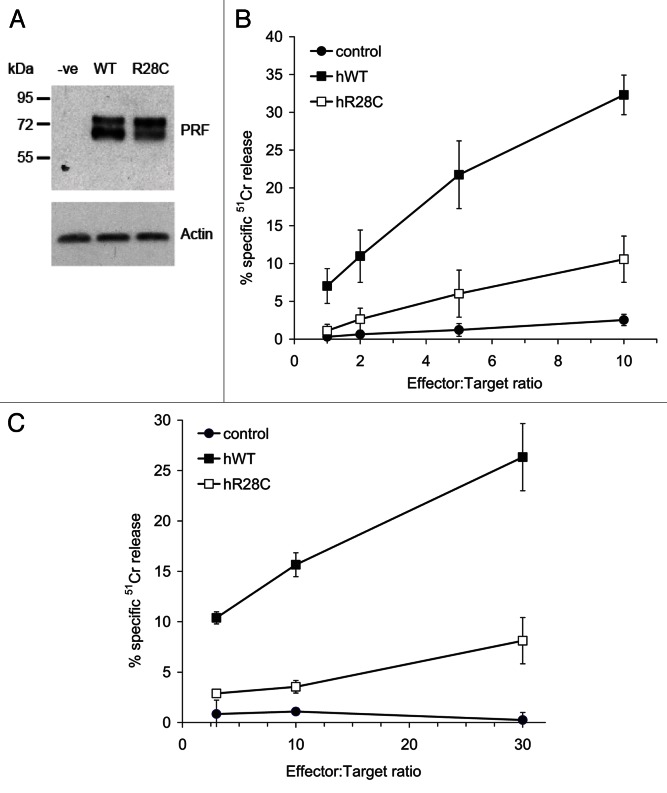

We tested 143 patients that had been diagnosed with malignant skin melanoma, an immunogenic cancer that has never been analyzed with respect to PRF1 mutations. Fourteen patients (9.8%) were positive for the A91V substitution, not significantly more than the control healthy population (7.6%) (Table 1). We were surprised to find two patients bearing a heterozygous mutation encoding PRF1R28C, which has recently been described for the first time in a patient affected by juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and the macrophage activation syndrome.20 As the original report had not characterized PRF1R28C functionally, we studied this PRF1 variant in a number of in vitro cytotoxicity assays. Using standard 4 h 51Cr release assays to quantify target cell death, we found that primary cytotoxic T lymphocytes from Prf1−/− mice expressing PRF1R28C exhibit a dramatic functional impairment (> 80%) as compared with the same cells expressing WT PRF1 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Effect of R28C mutation on perforin function. The gel panel shows a western blot for perforin levels in transiently-transfected RBL cells (A). Results of representative cytotoxicity assays are shown for a RBL cytotoxicity assay (B), and an assay using CD8+ T cells from Prf1−/−.OT-1 mice (C). Data points represent the mean values from 3 experiments ± standard error of the mean. In all of these experiments, effector cells were electroporated with human wild-type or R28C mutant PRF1 cloned into pIRES2-eGFP expression vector. Transfected cells were isolated on the basis of identical eGFP fluorescence and their cytotoxic activity against 51Cr labeled and trinitrobenzosulfonic acid-labeled Jurkat cells (in the case of RBL effectors) or SIINFEKL (ova) peptide pulsed EL-4 target cells (in the case of CD8+ Tcells), were tested as described in Materials and Methods.

Including PRF1R28C in the analysis brought the overall incidence of PRF1 variants in the melanoma patient cohort to 11.2% (16/143, Table 1). When we checked the annotated clinical histories of all these patients, we noted that both PRF1R28C-bearing individuals as well as two PRF1A28V-bearing subjects had also experienced B-cell lymphoma. Our melanoma patient cohort included a total of 15 individuals who had experienced both melanoma and B-cell lymphoma, and 4/15 (26.7%) of these subjects were heterozygous for a pathological PRF1 mutation, be it A91V or R28C (p = 0.04). We identified additional 28 patients who had melanoma and a second primary malignancy other than B-cell lymphoma, three of whom were positive for A91V while one carried PRF1N252S, which has previously been reported to have normal activity.19 Globally, PRF1 mutations were hence identified in 8 out of 43 subjects who had experienced melanoma and another malignancy, corresponding to 18.6% of this patient subgroup (p = 0.08).

Among patients diagnosed with two cancers including a melanoma, the time interval between the two diagnoses widely varied between a synchronous diagnosis and 25 y, and a similar proportion of patients developed melanoma as the first or second malignancy (48.5% or 51.5%, respectively). This was also the case for individuals diagnosed with both melanoma and B-cell lymphoma during their lifetime. However, it was interesting to note that melanoma was diagnosed relatively early (mean = 44.8 y, n = 4) in patients bearing a PRF1 mutation as compared with individuals carrying WT PRF1 in homozygosity (mean = 63.3 y, n = 11). By contrast, hematological malignancies developed at a similar age irrespective of whether the patients carried a PRF1 mutation (mean = 56.8 y) or not (mean = 59.6 y).

Discussion

The specific and pronounced susceptibility of Prf1−/− mice to develop spontaneous B-cell lymphomas indicates that, at least in mice, the immune system in general and CLs in particular play an important role in eliminating transformed cells before tumors become clinically evident. The rarity of FHL and the fact that PRF1-deficient children do not often survive infancy has made it very difficult to ascertain whether a similar mechanism also exists in humans, although previous studies have found evidence in support of this contention.13,16 We have previously shown that PRF1 is likely to protect humans against hematological cancers, as of all non-consanguineous patients recorded in the literature bearing bi-allelic PRF1 mutations including PRF1A91V (n = 26) but remaining disease-free to the age of > 10 y, 50% presented with a spectrum of hematological cancers.12

The current study aimed to examine the incidence of mono-allelic PRF1A91V and when possible, other PRF1 mutations in populations of adult individuals affected by lymphoma or epithelial malignancies. We elected to study several hundred patients previously diagnosed with melanoma, lymphoma, ovarian cancer or colorectal cancer, diseases in which there is independent evidence in support of a role for CD8+ T cells in the prevention of disease progression and/or metastasis. Melanoma has long been recognized as an “immunogenic” cancer, one of the few human malignancies in which circulating CTLs with overt antitumor activity ex vivo can be easily isolated.21,22 In both ovarian and colorectal carcinoma, tumor infiltration by CD8+ lymphocytes has been associated with a favorable patient prognosis.23 This is particularly the case for colorectal cancer, in which the degree of lymphocytic infiltration has been claimed to be a more reliable predictor of overall survival than cancer stage at the time of diagnosis.24 We found a marginal increase in the frequency of PRF1 mutations among 143 melanoma patients (11.9%, comprising 14 PRF1A91V-positive individuals, 2 patients bearing the rare PRF1R28C allele and 1 subject carrying PRF1N252S), as compared with a healthy, gender-matched control population. Still, the PRF1 mutation appeared to be particularly enriched in melanoma patients who had also been diagnosed with a second malignancy, mainly B-cell lymphoma. Although this was a small sub-group, melanoma occurred at a relatively early age among the carriers of mutant PRF1, supporting the notion that PRF1 mutations negatively influence immunosurveillance, hence accelerating the development of clinically manifest lesions.

In our opinion, it is unlikely that the treatment for melanoma predisposed patients to B-cell lymphoma or vice versa. Surgical excision, interferon treatment (rarely used) and radiotherapy are indeed unlikely to cause any of the second malignancies seen among melanoma patients, and the chemotherapy for advanced melanoma does not involve anthracyclines (which have previously been implicated in the development of secondary acute myeloid leukemia). Along similar lines, there is no therapeutic approach for hematological malignancies known to predispose to melanoma, exception made—perhaps—for therapy-related immunosuppression itself, which is transient in successfully treated individuals.

How then, in a mechanistic sense, could mono-allelic PRF1 mutations adversely affect cancer immunosurveillance, given a co-dominant allelic expression? We have previously shown that PRF1A91V can exert a “dominant negative” effect, that is, it can substantially reduce the activity of WT PRF1 with which it is packaged in CL granules.15 As granzymes are entirely dependent on PRF1 to effect apoptosis,25 it is possible the presence of PRF1A91V might substantially reduce the overall cytotoxic activity of CLs, even when WT PRF1 is co-expressed. While evidence in support of this hypothesis is still lacking, it is also possible that polymorphisms affecting the large and complicated PRF1 promoter/enhancer might impact negatively on PRF1 as produced by the WT allele, so that PRF1A91V or PRF1R28C would be synthetized in relative excess. Further studies are needed to investigate this possibility.

This is the first report linking a partial loss of PRF1 activity to a non-hematological neoplasm, melanoma. Given the small number of patients bearing dual primary cancers included in our study, we look forward to other groups testing our conclusions in independent patient cohorts. As CLs play a critical role in killing virus-infected cells, we are also interested in determining whether PRF1 defects affect the incidence or clinical course of malignancies that have a viral etiology.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Melanoma Research Alliance (MRA), Victorian Cancer Agency (VCA), the Victorian State Government Operational Infrastructure Support Program and the NHMRC Independent Research Institutes Infrastructure Support Scheme.

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/oncoimmunology/article/24185

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1.Voskoboinik I, Smyth MJ, Trapani JA. Perforin-mediated target-cell death and immune homeostasis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:940–52. doi: 10.1038/nri1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Voskoboinik I, Dunstone MA, Baran K, Whisstock JC, Trapani JA. Perforin: structure, function, and role in human immunopathology. Immunol Rev. 2010;235:35–54. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kägi D, Hengartner H. Different roles for cytotoxic T cells in the control of infections with cytopathic versus noncytopathic viruses. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:472–7. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(96)80033-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Street SE, Cretney E, Smyth MJ. Perforin and interferon-gamma activities independently control tumor initiation, growth, and metastasis. Blood. 2001;97:192–7. doi: 10.1182/blood.V97.1.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van den Broek ME, Kägi D, Ossendorp F, Toes R, Vamvakas S, Lutz WK, et al. Decreased tumor surveillance in perforin-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1781–90. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smyth MJ, Thia KY, Street SE, MacGregor D, Godfrey DI, Trapani JA. Perforin-mediated cytotoxicity is critical for surveillance of spontaneous lymphoma. J Exp Med. 2000;192:755–60. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.5.755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stepp SE, Dufourcq-Lagelouse R, Le Deist F, Bhawan S, Certain S, Mathew PA, et al. Perforin gene defects in familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Science. 1999;286:1957–9. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henter JI, Elinder G, Söder O, Ost A. Incidence in Sweden and clinical features of familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991;80:428–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1991.tb11878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Janka GE. Familial and acquired hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Annu Rev Med. 2012;63:233–46. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-041610-134208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trottestam H, Horne A, Aricò M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Gadner H, et al. Histiocyte Society Chemoimmunotherapy for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: long-term results of the HLH-94 treatment protocol. Blood. 2011;118:4577–84. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-356261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124–31. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chia J, Yeo KP, Whisstock JC, Dunstone MA, Trapani JA, Voskoboinik I. Temperature sensitivity of human perforin mutants unmasks subtotal loss of cytotoxicity, delayed FHL, and a predisposition to cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9809–14. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903815106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta PA, Davies SM, Kumar A, Devidas M, Lee S, Zamzow T, et al. Children’s Oncology Group Perforin polymorphism A91V and susceptibility to B-precursor childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Leukemia. 2006;20:1539–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishii E, Ohga S, Imashuku S, Kimura N, Ueda I, Morimoto A, et al. Review of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) in children with focus on Japanese experiences. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;53:209–23. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2004.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Voskoboinik I, Sutton VR, Ciccone A, House CM, Chia J, Darcy PK, et al. Perforin activity and immune homeostasis: the common A91V polymorphism in perforin results in both presynaptic and postsynaptic defects in function. Blood. 2007;110:1184–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-072850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santoro A, Cannella S, Trizzino A, Lo Nigro L, Corsello G, Aricò M. A single amino acid change A91V in perforin: a novel, frequent predisposing factor to childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia? Haematologica. 2005;90:697–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baxter SW, Choong DY, Eccles DM, Campbell IG. Transforming growth factor beta receptor 1 polyalanine polymorphism and exon 5 mutation analysis in breast and ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:211–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng L, Baumann U, Reymond JL. An efficient one-step site-directed and site-saturation mutagenesis protocol. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voskoboinik I, Thia MC, Trapani JA. A functional analysis of the putative polymorphisms A91V and N252S and 22 missense perforin mutations associated with familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Blood. 2005;105:4700–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-12-4935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vastert SJ, van Wijk R, D’Urbano LE, de Vooght KM, de Jager W, Ravelli A, et al. Mutations in the perforin gene can be linked to macrophage activation syndrome in patients with systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:441–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clementi R, Dagna L, Dianzani U, Dupré L, Dianzani I, Ponzoni M, et al. Inherited perforin and Fas mutations in a patient with autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome and lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1419–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaugler B, Van den Eynde B, van der Bruggen P, Romero P, Gaforio JJ, De Plaen E, et al. Human gene MAGE-3 codes for an antigen recognized on a melanoma by autologous cytolytic T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;179:921–30. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nelson BH. The impact of T-cell immunity on ovarian cancer outcomes. Immunol Rev. 2008;222:101–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Berger A, Bindea G, Meatchi T, et al. Histopathologic-based prognostic factors of colorectal cancers are associated with the state of the local immune reaction. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:610–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.5425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lopez JA, Susanto O, Jenkins MR, Lukoyanova N, Sutton VR, Law RH, et al. Perforin forms transient pores on the target cell plasma membrane to facilitate rapid access of granzymes during killer cell attack. Blood. 2013;121:2659–2668. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-07-446146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.