Abstract

Objective

To investigate the association between overeating (without loss of control) and binge eating (overeating with loss of control) and adverse outcomes.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

Adolescents and young adults living throughout the United States.

Participants

16,882 males and females participating in the Growing Up Today Study who were 9–15 years old at enrollment in 1996.

Main Exposure

Overeating and binge eating assessed via questionnaire every 12–24 months between 1996 and 2005.

Main Outcome Measures

Risk of becoming overweight or obese, starting to binge drinking frequently, starting to use marijuana, starting to use other drugs, and developing high levels of depressive symptoms. Generalized estimating equations were used to estimate associations. All models controlled for age and sex; additional covariates varied by outcome.

Results

Among this large cohort of adolescents and young adults, binge eating is more common among females than males. In fully-adjusted models, binge eating, but not overeating, was associated with incident overweight/obesity (OR=1.73, 95% CI=1.11, 2.69) and with the onset of high depressive symptoms (OR=2.19, 95% CI=1.40, 3.45). Neither overeating nor binge eating was associated with starting to binge drink frequently, while both overeating and binge eating predicted starting to use marijuana and other drugs.

Conclusions

Although any overeating, with or without loss of control, predicted the onset marijuana and other drug use, we found that binge eating is uniquely predictive of incident overweight/obesity and the onset of high depressive symptoms. These findings suggest that loss of control is an important indicator of severity of overeating episodes.

INTRODUCTION

The DSM-IV defines binge eating as (1) eating, in a discrete period of time, an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat in a similar period of time under similar circumstances and (2) feeling a lack of control over eating during the episode.1 Binge eating among treatment seeking obese adolescents is common2,3 and overweight and obese adolescents are far more likely than their healthy weight peers to report binge eating.4,5 Moreover, adolescents who binge have higher levels of eating-disordered attitudes3 and more symptoms of anxiety3. In addition, binge eating has been found to predict excess weight gain6,7 and obesity onset8,9 among adolescents. Binge Eating Disorder (BED), defined as binge eating which occurs at least once a week for three months, is strongly associated with mood and anxiety disorders and substance abuse in adolescents.10 Although binge eating appears to be common in youth10–15, there is ongoing debate over how it should be defined, in part because determining what portion of food should be considered larger than normal is challenging in the present food environment where extra-large portion sizes have become the norm.16 Some have argued that loss of control (LOC), not overeating itself, is the crucial element in binge eating.17,18

LOC eating (hereafter referred to as binge eating) is cross-sectionally associated with higher weight, greater anxiety, more depressive symptoms, and more body dissatisfaction among children.19 Children with binge eating also exhibit more impulsivity, lower self-directedness, cooperativeness, and greater novelty seeking.20 Furthermore, youth who report binge eating consume a greater percentage of energy from carbohydrates, largely due to intake of dessert and snack foods21,22 and may have poorer recall of sweet food consumption.23 In prospective studies of children, binge eating has been found to predict weight gain24, disordered eating attitudes25, and higher depressive symptoms.25

Among adolescents, binge eating is cross-sectionally associated with obesity12, drug and alcohol use10,26, negative psychological experiences such as lower body satisfaction and self-esteem27, and mental disorders.10 Prospective studies of adolescent girls find that eating pathology including binge eating predicts weight gain7,8, the onset of high depressive symptoms28, and increases in substance abuse.29 However, there are no prospective studies which separately explore the consequences of overeating and binge eating among adolescents. Such studies could further substantiate the importance of LOC as a diagnostic feature or severity indicator of overeating episodes. The aim of the present study was to explore whether overeating and binge eating are prospectively associated with adverse health outcomes such as overweight/obesity, depressive symptoms, frequent binge drinking, marijuana use, and other drug use. Further, we sought to assess whether the risks are similar for adolescents who did and did not experience LOC during overeating episodes.

METHODS

Sample

Participants are members of the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS), an ongoing cohort study of adolescents throughout the United States that was established in 1996. GUTS recruited children of women participating in the ongoing Nurses’ Health Study II (NHSII), a cohort study of over 116,000 female registered nurses established in 198930. At enrollment in 1996, GUTS participants were 9 to 14 years old. Approximately 68% of the invited female participants (n=9,039) and 58% of the invited male participants (n=7,843) returned completed questionnaires, thereby assenting to participate in the cohort study. GUTS participants were asked to complete questionnaires annually from 1996 to 2001, and then biennially through 2007. The data collection periods in the 2001, 2003, 2005, and 2007 cycles spanned approximately 2 years. The study was approved by the human subjects committees at Children’s Hospital Boston and Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, MA.

Participants who provided information in one or more consecutive questionnaire cycles between 1996–2007 were included in the present analysis. Participants who were prevalent cases at baseline were censored from the analyses for that outcome. Incident cases were censored from analyses of subsequent time periods. After these exclusions, 10,246 participants remained for the analyses predicting becoming overweight or obese, 7,694 participants remained for the analyses predicting the development of high levels of depressive symptoms, 10,100 participants remained for the analyses predicting starting to binge drink frequently, 7,513 participants remained for the analyses predicting the onset of marijuana, and 8,000 participants remained for the analyses predicting starting to use other drugs. Of the 16,882 participants who completed the baseline questionnaire, 14,166 (83.9%) were included in the analyses of at least one of the five outcomes.

Measures

Overeating status

Overeating status is a three-level variable representing no overeating, overeating, or binge eating. Overeating and binge eating were assessed on all questionnaires using a two part question. Participants were first asked how often during the past year they had eaten a very large amount of food. Participants who reported eating a very large amount of food at least occasionally were asked a follow-up question about whether they felt out of control (yes/no) during these episodes, like they could not stop eating even if they wanted to stop. We defined overeating as at least weekly episodes of eating a large amount of food, but with no LOC during the episodes. We defined binge eating as at least weekly episodes of eating a large amount of food with LOC during the episodes based on frequency criteria for BED proposed for the fifth edition of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5).31

Weight Status

We calculated body mass index (BMI) [wt (kg)/ht (m)2] using self-reported weight and height which was assessed on all questionnaires. Children and adolescents younger than 18 years were classified as overweight or obese based on age- and gender-specific International Obesity Task Force (IOTF) cut-offs.32 Participants 18 years or older were classified as overweight if they had a BMI between 25 and 30 and obese if they had a BMI greater than 30. Studies of the validity of self-reported weight and height find that adolescents generally provide valid information.33–36

Depressive symptoms

We assessed depressive symptoms in 1999, 2001, and 2003 using the six item validated scale of the McKnight Risk Factor Survey (MRFS) IV.37 All responses were scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from never to always. In 2007, we used the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CESD-10) to measure depressive symptoms.38 Participants in the top decile of depressive symptoms were considered cases. We classified females who were in one of the bottom nine deciles of depression symptoms on one assessment and in the top decile on the next assessment as incident cases of high levels of depressive symptoms.

Binge drinking

A question on binge drinking was asked on the 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2003, and 2007 questionnaires. Children who reported that they ever consumed alcohol were asked a series of questions about their drinking behavior. We assessed binge drinking using one question which asked about the frequency of drinking four or more drinks over a few hours in the past year.39 Although studies of adult binge drinking use a monthly frequency cutoff40, we used a more conservative cutoff given the young age of our sample and the related low prevalence of monthly binge drinking during the early waves of assessment. Instead, we used a frequency cutoff of at least 6 episodes of binge drinking per year which would be appropriate across the ages represented in all waves of analyses

Drug use

Questions on drug use were included on the 1999, 2001, 2003, and 2007 questionnaires. Participants were asked a series of questions about drug use. The questions regarding illicit drug use asked whether they had used marijuana or hashish, cocaine, crack (1999 and 2001), heroin, ecstasy, PCP (1999 and 2001), GHB (1999, 2001, and 2007), LSD, mushrooms, ketamine (1999 and 2001), crystal meth (2007), Rohypnol, and amphetamines. In 2007, questions about the use of prescription drugs such as tranquilizers, pain killers, sleeping pills, and stimulants without a prescription were asked. Participants who reported using marijuana or hashish and had never reported using it at an earlier time period were classified as incident marijuana use cases. Participants who reported using any illicit drug, except marijuana or hashish, or prescription drug without a prescription and had never reported using any of those drugs at an earlier time period were classified as incident drug use cases.

Analysis

We modeled the log-odds of the hazard rate for the five outcomes using PROC GENMOD (SAS version 9.2). The models were fit using generalized estimating equations (GEE) with an independent working covariance matrix and empirical variance to account for the correlation between siblings. We conducted a lagged analysis with time-varying covariates so that outcomes were modeled as a function of predictors assessed on the previous questionnaire. All models controlled for age and sex. Additional covariates varied by outcome. In models predicting the development of overweight/obesity, BMI and dieting were adjusted for in the final models. In analyses predicting starting to binge drink frequently, starting to use marijuana, starting to use other drugs, and developing high depressive symptoms, fully-adjusted models included having friends who use drugs, having > 1 friend who drinks, having a sibling who uses drugs, and having a sibling who started drinking before age 18. Models predicting developing high depressive symptoms additionally adjusted for BMI. We tested for an interaction between overeating status and sex in fully-adjusted models for all outcomes. For both overeating without LOC and binge eating, we report the odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for developing our five outcomes with individuals who report no overeating as the referent group.

RESULTS

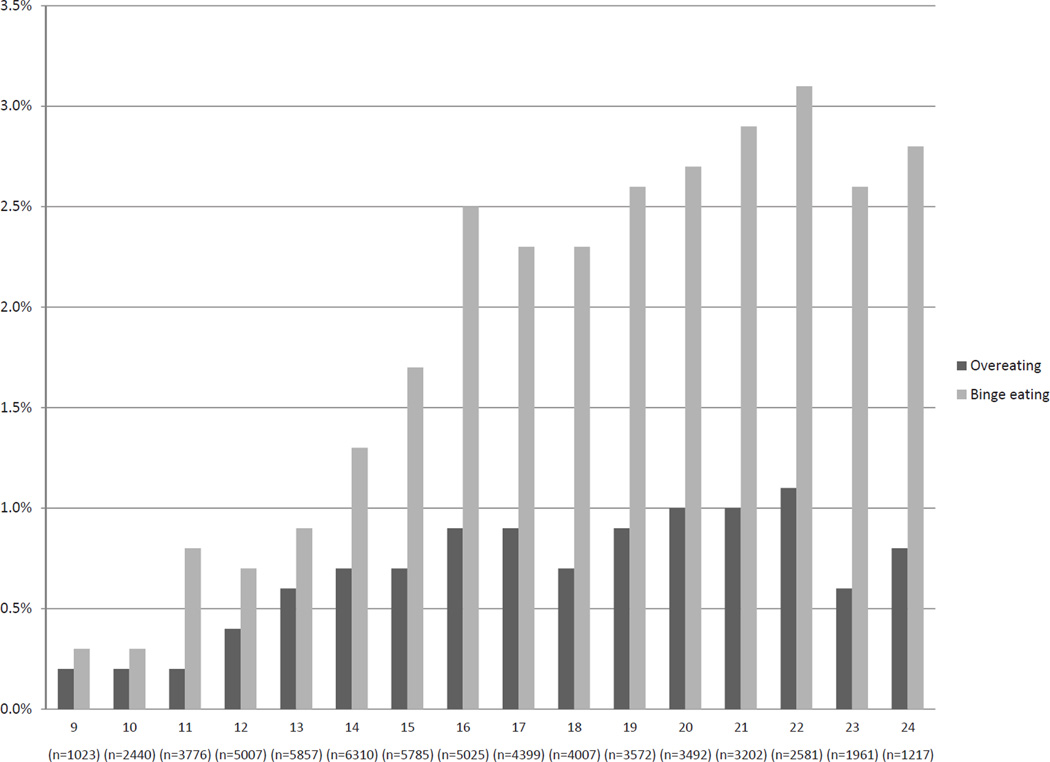

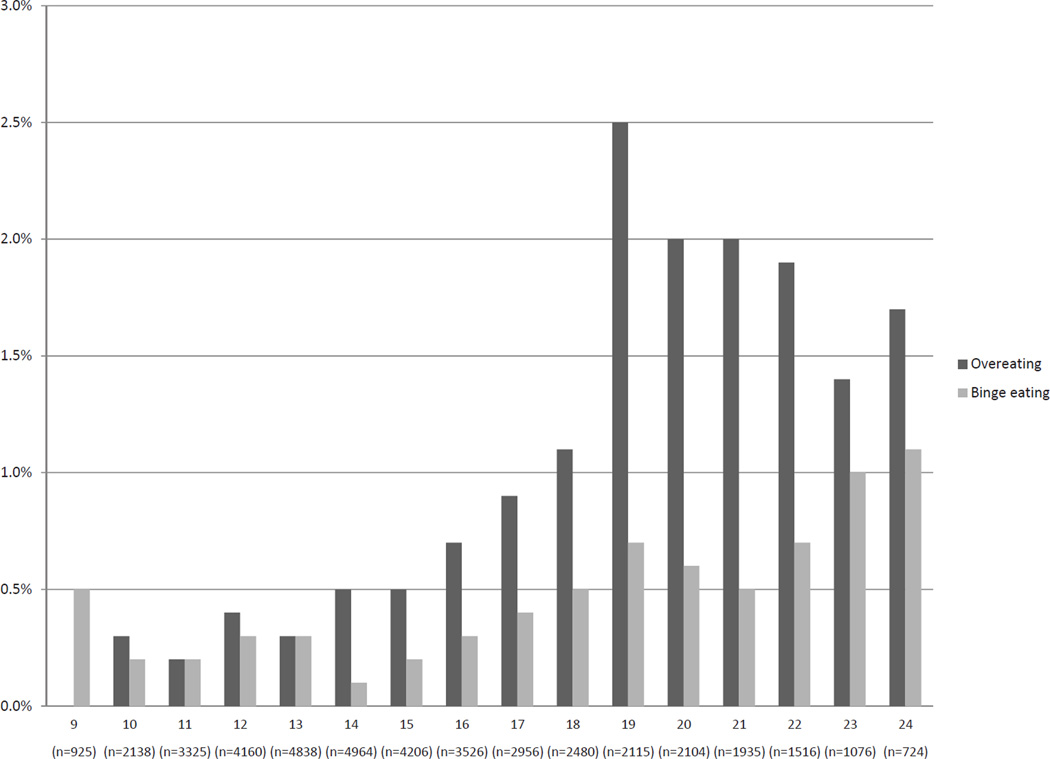

At baseline in 1996, the mean (sd) age of the participants was 11.0 (1.6) years (Table 1). At time of first measurement, 22.3% of participants were overweight or obese, 4.3% of participants were binge drinking frequently, 12.2% had used marijuana, and 9.1% had used a drug other than marijuana. The pattern of overeating and binge eating differed by sex. Among females, the prevalence of binge eating exceeded the prevalence of overeating at all ages (Figure 1). Conversely, the prevalence of overeating exceeded the prevalence of binge eating at all ages among males (Figure 2). Among females, the prevalence of either overeating or binge eating tended to increase with age with 0.5% of the sample endorsing either overeating or binge eating at age 9 and 3.6% of the sample endorsing one of the behaviors at age 24 (Figure 1). The prevalence of either overeating or binge eating also generally increased with age during adolescence among males, but peaked at 3.2% at age 19 (Figure 2). Binge eating is more common among females than males with 2.3–3.1% of females and 0.3–1.0% of males reporting binge eating between the ages 16 and 24.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of female and male participants in the Growing Up Today Study

| n | Mean (sd) / % prevalence(n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in 1996 (years) | 16,882 | 12.0 (sd=1.6) |

| Overweight or obese* | 16,557 | 22.3% (n=3,689) |

| Binge drinks frequently¶ | 10,558 | 4.3% (n=452) |

| Uses marijuana§ | 10,759 | 12.2% (n=1,314) |

| Uses drugs other than marijuana§ | 10,788 | 9.1% (n=977) |

First assessed in 1996

First assessed in 1998

First assessed in 1999

Figure 1.

Prevalence of at least weekly overeating and binging episodes among females in the Growing Up Today Study from 1996 to 2007.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of at least weekly overeating and binging episodes among males in the Growing Up Today Study from 1996 to 2007.

Between 1996 and 2007, 30.7% (n=3,143) became overweight or obese. Between 1999 and 2007, 60.0% (n=6,065) started binge drinking frequently. From 2001 to 2007, 40.7% (n=3,061) of participants started to use marijuana, 31.9% (n=2,549) started to use other drugs, and 22.5% (n=1,732) developed high levels of depressive symptoms.

As shown in Table 2, binge eating, but not overeating, was associated with incident overweight/obesity in age- and sex-adjusted models (OR=1.74, 95% CI=1.18, 2.57) and in fully-adjusted models (OR=1.73, 95% CI=1.11, 2.69). Similarly, binge eating, but not overeating, was significantly associated with the onset of high depressive symptoms in age- and sex-adjusted models (OR=1.98, 95% CI=1.33, 2.93) and in fully-adjusted models (OR=2.19, 95% CI=1.40, 3.45). Neither overeating nor binge eating was associated with starting to binge drink frequently in either age- and sex-adjust or fully-adjusted models, while both overeating and binge eating predicted starting to use marijuana and starting to use other drugs. In fully-adjusted models, both overeating (OR=2.67, 95% CI=1.68, 4.23) and binge eating (OR=1.85, 95% CI=1.27, 2.67) were significantly associated with starting to use marijuana. Both overeating (OR=1.89, 95% CI=1.18, 3.02) and binge eating (OR=1.59, 95% CI=1.08, 2.33) were significantly associated with starting to use drugs in fully-adjusted models.

Table 2.

Associations of weekly overeating or binging and the onset of adverse outcomes among males and females in the Growing Up Today Study

| Age and Sex-adjusted* OR (95% CI) |

Fully Adjusted* OR (95% CI) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No overeating |

Overeating | Binge eating |

No overeating |

Overeating | Binge eating | |

| Overweight/ obesity§ | 1 (ref) |

1.48 (0.96 2.29) |

1.74 (1.18, 2.57) |

1 (ref) |

1.24 (0.70, 2.21) |

1.73 (1.11, 2.69) |

| High depressive symptoms† | 1 (ref) |

1.58 (0.95, 2.62) |

1.98 (1.33, 2.93) |

1 (ref) |

1.58 (0.83, 3.03) |

2.19 (1.40, 3.45) |

| Frequent binge drinking‡ | 1 (ref) |

1.15 (0.80, 1.67) |

1.38 (1.06, 1.80) |

1 (ref) |

1.01 (0.64, 1.57) |

1.14 (0.83, 1.57) |

| Marijuana use‡ | 1 (ref) |

2.32 (1.60, 3.36) |

2.16 (1.58, 2.96) |

1 (ref) |

2.67 (1.68, 4.23) |

1.85 (1.27, 2.67) |

| Other drugs use‡ | 1 (ref) |

1.52 (1.01, 2.29) |

1.91 (1.39, 2.62) |

1 (ref) |

1.89 (1.18, 3.02) |

1.59 (1.08, 2.33) |

Lagged analysis, using generalized estimating equations

Fully adjusted model for overweight/obesity adjusted for sex, age, BMI, and dieting

Fully adjusted model for developing high depressive symptoms adjusted for sex, age, BMI, having ≥ 1 parent who drinks, having a sibling who started drinking before age 18, having ≥ 1 friend who drinks, having a sibling who uses drugs, and having friends who use drugs

Fully adjusted model for starting to binge drink frequently, starting to use drugs, and starting to use marijuana adjusted for sex, age, having ≥ 1 parent who drinks, having a sibling who started drinking before age 18, having ≥ 1 friend who drinks, having a sibling who uses drugs, and having friends who use drugs

We saw no significant interactions between overeating status and sex, although the p-value for the interaction term between overeating status and sex approached significance in the models predicting the onset of high depressive symptoms (p=0.08) and frequent binge drinking (p=0.08). In sex-stratified analyses, overeating predicted the onset of high depressive symptoms among females (OR=2.85, 95% CI=1.31, 6.20), but not males (OR=0.52, 95% CI=0.12, 2.21), while binge eating was associated with the onset of high depressive symptoms among both females (OR=2.12, 95% CI=1.32, 3.40) and males (OR=3.21, 95% CI=0.68, 15.27). The non-significant association seen among males is likely a reflection of limited power due to low prevalence of binge eating among males. Although the main effect of overeating status on the onset of frequent binge drinking was null, overeating predicted the onset of frequent binge drinking among males (OR=2.02, 95% CI=1.05, 3.89), but not females (OR=0.68, 95% CI=0.37, 1.25). Binge eating was not associated with the onset of frequent binge drinking among either females (OR=1.15, 95% CI=0.83, 1.59) or males (OR=1.13, 95% CI=0.36, 3.55).

DISCUSSION

Among this large cohort of adolescents and young adults, binge eating is more common among females than males with 2.3–3.1% of females and 0.3–1.0% of males reporting binge eating between the ages 16 and 24. Excluding prevalent cases at first measurement, about 20% of participants developed high depressive symptoms, about 30% became overweight/ obese or started to use drugs other than marijuana, about 40% started using marijuana, and about 60% started binge drinking frequently during the 6–10 years of follow-up.

We observed that the association between binge eating and overeating and the development of adverse outcomes differed by outcome. We found that overeating, but not binge eating, predicted incident overweight/obesity and the onset of high depressive symptoms. In accordance with a recent review41 and previous research which suggests that the presence of LOC, rather than quantity of food consumed, is associated with eating disordered cognitions17,25,42,43 and greater distress19,44, these findings suggest that LOC is a unique and important feature of overeating episodes and should be retained as a diagnostic criteria. In contrast, we did not observe differences in the association between overeating and binge eating for binge drinking, starting to use marijuana, or starting to use other drugs. We observed that participants who reported either binge eating or overeating were more likely to start using marijuana or other drugs than those who reported no overeating episodes. Neither binge eating nor overeating was associated with starting to binge drink frequently.

To our knowledge, this is first study to prospectively examine the associations of both overeating and binge eating and adverse outcomes among adolescents. Our findings align with those of a cross-sectional study of adolescents from Minnesota which found that binge eating, but not overeating, was associated with negative psychological experiences.27 Specifically, girls who reported binge eating had greater body dissatisfaction, lower self esteem, more depressed mood, and higher suicide risk than those who reported overeating, but not binge eating.27 Our study adds to the growing literature exploring the consequences of binge eating among adolescents. Our findings that binge eating predicts the onset of high depressive symptoms replicates previous work in children25 and adolescent girls28 which suggests that elevated binge eating predicts an increase in depressive symptoms, perhaps because of the shame and guilt associated with these behaviors28. Although one longitudinal study of children found that baseline binge eating predicted subsequent elevated depressive symptoms only if participants engaged in binge eating throughout the follow-up.25 Our finding that binge eating predicts later weight gain is supported most,7,8,24 but not all45, by prospective studies of children and adolescents. Similarly, a longitudinal association between eating pathology and substance abuse has been reported in a previous study of adolescents.29

This investigation has several limitations. Our sample is more than 90% white and likely under represents youth of low socioeconomic status (SES) because the our sample consists of children of nurses, thus it is unclear if our results are generalizable to racial/ethnic minorities or adolescents of low SES. Further, we relied on self-reports, which may have resulted in some misclassification. Self-reported weight and height, which were used in the ascertainment of weight status, have been observed to be highly valid.33–35 Although our measure of binge eating has been validated46, studies have demonstrated a number of limitations of self-reported binge eating in children and adolescents.47 The inclusion of instructions defining "large amount" has been useful in reducing these limitations47,48, though such instructions were not included in our study. As such, our measurement of overeating should more accurately be described as perceived overeating and may not represent objective overeating episodes. Although assessing LOC eating, rather than binge eating, is preferred when working with children and adolescents in order to be inclusive of all episodes involving LOC17, we were not able to identify participants who experience LOC while eating in the absence of perceived overeating episodes because participants who did not report overeating were not asked whether they ever felt LOC while eating. Although interactions between overeating status and sex failed to meet significance, it is notable that females make up the majority of binge eating cases in our sample. Known gender differences in the experience of a binge may contribute to the disproportionate prevalence observed49 and ongoing research is needed to explore differences in definition and assessment of binge eating between males and females.

The strengths of the study outweigh the limitations. This is the largest prospective study to follow a sample through adolescence and into young adulthood, a period of high risk for developing overweight/obesity and high depressive symptoms and for starting to use drugs or binge drink frequently. Binge eating and overeating were assessed every 12–24 months and we had multiple measurements of adverse outcomes in addition to information on a wide range of confounders. Moreover, this is the first study to examine whether perceived overeating without LOC is predictive of adverse outcomes.

In summary, we found that binge eating, but not overeating predicted the onset of overweight/obesity and of worsening depressive symptoms. We further observed that any overeating, with or without loss of control, predicted the onset of marijuana and other drug use. Findings from this investigation and previous research suggest that LOC is an important indicator of severity of overeating episodes and highlight the importance of ascertaining LOC, in addition to whether adolescents engage in overeating episodes. Given that binge eating is uniquely predictive of some adverse outcomes and because previous work has found that binge eating is amenable to intervention,50,51 clinicians should be encouraged to screen adolescents for binge eating. Moreover, school and community-based interventions focused on prevention of binge eating might prevent both eating disorders and obesity among children, adolescents, and young adults.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

The analysis was supported by a research grant (MH087786-01, PI: Field) from the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Kendrin R. Sonneville, Division of Adolescent Medicine, Department of Medicine, Children’s Hospital Boston and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; Channing Laboratory, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Nicholas J. Horton, Department of Mathematics and Statistics, Smith College, Northampton, MA.

Nadia Micali, University College London, Institute of Child Health, Behavioural and Brain Sciences Unit, London, UK.

Ross D. Crosby, Neuropsychiatric Research Institute and Department of Clinical Neuroscience, University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Fargo, ND.

Sonja A. Swanson, Department of Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA.

Francesca Solmi, University College London, Institute of Child Health, Behavioural and Brain Sciences Unit, London, UK.

Alison E. Field, Division of Adolescent Medicine, Department of Medicine, Children’s Hospital Boston and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; Channing Laboratory, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; Department of Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fourth Edition. Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Decaluwé V, Braet C, Fairburn CG. Binge eating in obese children and adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2003;33:78–84. doi: 10.1002/eat.10110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glasofer DR, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Eddy KT, et al. Binge Eating in Overweight Treatment-Seeking Adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:95–105. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Field AE, Camargo CA, Jr, Taylor CB, et al. Overweight, Weight Concerns, and Bulimic Behaviors Among Girls and Boys. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:754–760. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Hannan PJ, Perry CL, Irving LM. Weight-Related Concerns and Behaviors Among Overweight and Nonoverweight Adolescents: Implications for Preventing Weight-Related Disorders. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:171–178. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Field AE, Austin SB, Taylor CB, et al. Relation Between Dieting and Weight Change Among Preadolescents and Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;112:900–906. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.4.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Haines J, Story M, Eisenberg ME. Why Does Dieting Predict Weight Gain in Adolescents? Findings from Project EAT-II: A 5-Year Longitudinal Study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2007;107:448–455. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stice E, Presnell K, Spangler D. Risk factors for binge eating onset in adolescent girls: A 2-year prospective investigation. Health Psychology. 2002;21:131–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haines J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Wall M, Story M. Personal, Behavioral, and Environmental Risk and Protective Factors for Adolescent Overweight[ast][ast] Obesity. 2007;15:2748–2760. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, Swendsen J, Merikangas KR. Prevalence and Correlates of Eating Disorders in Adolescents: Results From the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:714–723. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stice E, Marti CN, Shaw H, Jaconis M. An 8-year longitudinal study of the natural history of threshold, subthreshold, and partial eating disorders from a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:587–597. doi: 10.1037/a0016481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Field AE, Camargo CA, Jr, Taylor CB, et al. Overweight, Weight Concerns, and Bulimic Behaviors Among Girls and Boys. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:754–760. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199906000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Croll J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Ireland M. Prevalence and risk and protective factors related to disordered eating behaviors among adolescents: relationship to gender and ethnicity. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:166–175. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00368-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Downes B, Resnick M, Blum R. Ethnic differences in psychosocial and health behavior correlates of dieting, purging, and binge eating in a population-based sample of adolescent females. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1997;22:315–322. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199711)22:3<315::aid-eat11>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cassidy OL, Matheson B, Osborn R, et al. Loss of control eating in African-American and Caucasian youth. Eating Behaviors. 2012;13:174–178. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis C, Curtis C, Tweed S, Patte K. Psychological factors associated with ratings of portion size: Relevance to the risk profile for obesity. Eating Behaviors. 2007;8:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shomaker LB, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Elliott C, et al. Salience of loss of control for pediatric binge episodes: Does size really matter? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;43:707–716. doi: 10.1002/eat.20767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pratt EM, Niego SH, Agras WS. Does the size of a binge matter? International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1998;24:307–312. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199811)24:3<307::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan CM, Yanovski SZ, Nguyen TT, et al. Loss of Control Over Eating, Adiposity, and Psychopathology in Overweight Children. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2002;31:430–441. doi: 10.1002/eat.10038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hartmann AS, Czaja J, Rief W, Hilbert A. Personality and psychopathology in children with and without loss of control over eating. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2010;51:572–578. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theim KR, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Salaita CG, et al. Children's descriptions of the foods consumed during loss of control eating episodes. Eating Behaviors. 2007;8:258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanofsky-Kraff M, McDuffie JR, Yanovski SZ, et al. Laboratory assessment of the food intake of children and adolescents with loss of control eating. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;89:738–745. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolkoff LE, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, et al. Self-reported vs. actual energy intake in youth with and without loss of control eating. Eating Behaviors. 2011;12:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Schvey NA, Olsen CH, Gustafson J, Yanovski JA. A prospective study of loss of control eating for body weight gain in children at high risk for adult obesity. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42:26–30. doi: 10.1002/eat.20580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Olsen C, et al. A prospective study of pediatric loss of control eating and psychological outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2011;120:108–118. doi: 10.1037/a0021406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross HE, Ivis F. Binge eating and substance use among male and female adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 1999;26:245–260. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199911)26:3<245::aid-eat2>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Perry C. Overeating Among Adolescents: Prevalence and Associations With Weight-Related Characteristics and Psychological Health. Pediatrics. 2003;111:67–74. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stice E, Hayward C, Cameron RP, Killen JD, Taylor CB. Body-image and eating disturbances predict onset of depression among female adolescents: A longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:438–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Measelle J, Stice E, Hogansen J. Developmental trajectories of co-occurring depressive, eating, antisocial, and substance abuse problems in female adolescents. J Abnorm Psychol. 2006;115:524–538. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solomon CG, Willett WC, Carey VJ, et al. A Prospective Study of Pregravid Determinants of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:1078–1083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Striegel-Moore R, Wonderlich S, Walsh B, Mitchell J. Developing an evidence-based classifciation of eating disorders: Scientific findings for DSM-5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Assoication; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH. Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ. 2000;320:1240–1243. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7244.1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goodman E, Hinden BR, Khandelwal S. Accuracy of Teen and Parental Reports of Obesity and Body Mass Index. Pediatrics. 2000;106:52–58. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strauss RS. Comparison of measured and self-reported weight and height in a crosssectional sample of young adolescents. International Journal of Obesity & Related Metabolic Disorders. 1999;23:904. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shannon B, Smiciklas-Wright H, Wang M. Inaccuracies in self-reported weights and heights of a sample of sixth-grade children. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1991;91:675–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Field AE, Aneja P, Rosner B. The Validity of Self-reported Weight Change among Adolescents and Young Adults[ast] Obesity. 2007;15:2357–2364. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shisslak CM, Renger R, Sharpe T, et al. Development and evaluation of the McKnight Risk Factor Survey for assessing potential risk and protective factors for disordered eating in preadolescent and adolescent girls. The International journal of eating disorders. 1999;25:195–214. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199903)25:2<195::aid-eat9>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Radloff L. The Use of the Center for Epidemiological Studies of Depression Scale in Adolescents and Young Adults. J Youth Adoles. 1991;20:149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. NIAAA council approves definition of binge drinking. NIAAA Newsletter. 2004;3:3. [Google Scholar]

- 40.National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2001 http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/nhsda/2k1nhsda/vol1/chapter3.htm.

- 41.Wolfe BE, Baker CW, Smith AT, Kelly-Weeder S. Validity and utility of the current definition of binge eating. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2009;42:674–686. doi: 10.1002/eat.20728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Faden D, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Yanovski JA. The perceived onset of dieting and loss of control eating behaviors in overweight children. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;38:112–122. doi: 10.1002/eat.20158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Marmarosh C, Morgan CM, Yanovski JA. Eating-Disordered Behaviors, Body Fat, and Psychopathology in Overweight and Normal-Weight Children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:53–61. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goldschmidt AB, Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, et al. Momentary Affect Surrounding Loss of Control and Overeating in Obese Adults With and Without Binge Eating Disorder. Obesity. 2011 doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stice E, Presnell K, Shaw H, Rohde P. Psychological and Behavioral Risk Factors for Obesity Onset in Adolescent Girls: A Prospective Study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:195–202. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Field AE, Taylor CB, Celio A, Colditz GA. Comparison of self-report to interview assessment of bulimic behaviors among preadolescent and adolescent girls and boys. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2004;35:86–92. doi: 10.1002/eat.10220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldschmidt AB, Doyle AC, Wilfley DE. Assessment of binge eating in overweight youth using a questionnaire version of the child eating disorder examination with instructions. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:460–467. doi: 10.1002/eat.20387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goldfein JA, Devlin MJ, Kamenetz C. Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire with and without instruction to assess binge eating in patients with binge eating disorder. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2005;37:107–111. doi: 10.1002/eat.20075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reslan S, Saules KK. College students’ definitions of an eating “binge” differ as a function of gender and binge eating disorder status. Eating Behaviors. 2011;12:225–227. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones M, Luce KH, Osborne MI, et al. Randomized, Controlled Trial of an Internet-Facilitated Intervention for Reducing Binge Eating and Overweight in Adolescents. Pediatrics. 2008;121:453–462. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Wilfley DE, Young JF, et al. A pilot study of interpersonal psychotherapy for preventing excess weight gain in adolescent girls at-risk for obesity. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;43:701–706. doi: 10.1002/eat.20773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]