Abstract

Although it is widely accepted that sleep must serve an essential biological function, little is known about molecules that underlie sleep regulation. Given that insomnia is a common sleep disorder that disrupts the ability to initiate and maintain restorative sleep, a better understanding of its molecular underpinning may provide crucial insights into sleep regulatory processes. Thus, we created a line of flies using laboratory selection that share traits with human insomnia. After 60 generations, insomnia-like (ins-l) flies sleep 60 min a day, exhibit difficulty initiating sleep, difficulty maintaining sleep, and show evidence of daytime cognitive impairment. ins-l flies are also hyperactive and hyperresponsive to environmental perturbations. In addition, they have difficulty maintaining their balance, have elevated levels of dopamine, are short-lived, and show increased levels of triglycerides, cholesterol, and free fatty acids. Although their core molecular clock remains intact, ins-l flies lose their ability to sleep when placed into constant darkness. Whole-genome profiling identified genes that are modified in ins-l flies. Among those differentially expressed transcripts, genes involved in metabolism, neuronal activity, and sensory perception constituted over-represented categories. We demonstrate that two of these genes are upregulated in human subjects after acute sleep deprivation. Together, these data indicate that the ins-l flies are a useful tool that can be used to identify molecules important for sleep regulation and may provide insights into both the causes and long-term consequences of insomnia.

Introduction

Sleep has been observed in all mammals, birds, reptiles, and invertebrates in which it has been thoroughly investigated (Shaw and Franken, 2003; Allada and Siegel, 2008). In mammals, sleep is not regulated from a single brain center or by a solitary neurotransmitter (Saper et al., 2005). Rather, sleep is modulated by a variety of neurochemicals operating through multiple neuronal systems distributed throughout the neuraxis (Borbély and Tobler, 1989; Obal and Krueger, 2003). Given the complexity of sleep regulation, it is not surprising that sleep disorders are highly prevalent in the general population. Although sleep disorders are believed to have a strong genetic component, it is rare for these disorders to be attributed to single gene defects (Tafti et al., 2005). Thus, sleep is a complex behavior that is regulated by many genes and their interactions.

This principle of a distributed sleep regulatory network also appears to be true for the genetic model organism Drosophila melanogaster (Joiner et al., 2006; Pitman et al., 2006; Foltenyi et al., 2007; Sheeba et al., 2008). Moreover, sleep in flies is also influenced by a variety of molecular pathways (Shaw et al., 2002; Andretic and Shaw, 2005; Cirelli et al., 2005; Kume et al., 2005; Foltenyi et al., 2007; Koh et al., 2008). Interestingly, a closer inspection of large populations of wild-type flies reveals that many individuals display disrupted sleep (Andretic and Shaw, 2005; Seugnet et al., 2008). As with humans, it is likely that the changes in sleep regulation observed in these individuals is attributable to modifications in many genes which may also increase the vulnerability of these individuals to sleep disruption (e.g., gene × environment interactions). Thus, populations of wild-type flies naturally possess sufficient genetic variability to induce complex sleep phenotypes.

Recently, several labs have used laboratory selection as an efficient strategy to identify genes that underlie complex behavior (Dierick and Greenspan, 2006; Edwards et al., 2006; Sørensen et al., 2007). Given that insomnia is a highly prevalent, naturally occurring condition that disrupts the ability to initiate and maintain restorative sleep, a better understanding of its molecular underpinning may provide crucial insights into sleep regulatory processes. Thus, we have used laboratory selection to create a unique line of flies that share many traits with human insomnia and have identified genes that are both important for sleep regulation and may provide insights into the causes and long-term consequences of insomnia.

Materials and Methods

Fly stocks, sleep monitoring, and sleep deprivation.

Canton-S (Cs) flies were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila stock center. Insomnia-like (ins-l) flies used for behavioral and molecular evaluation were obtained from generation 65 to 85 of the selection. Flies were cultured at 25°C, 50–60% humidity, in a 12 h light/dark (LD) cycle, on a standard food containing yeast, dark corn syrup, molasses, dextrose, and agar. Newly eclosed female adult flies were collected from culture vials daily under CO2 anesthesia. Three-day-old flies were then individually placed into 65 mm glass tubes so that sleep parameters could be continuously evaluated using the Trikinetics activity monitoring system as described previously (Shaw et al., 2000). Flies were sleep deprived using an automated sleep deprivation apparatus that has been found to produce waking without nonspecifically activating stress responses (Shaw et al., 2002). The Sleep Nullifying Apparatus (SNAP) tilts asymmetrically from −60° to +60°, such that sleeping flies are displaced during the downward movement six times per minute. This stimulus is effective presumably because it initiates a geotactic response. The SNAP effectively eliminates all sleep (Shaw et al., 2000). Thus, 100% of the sleep that would normally occur during stimulation is abolished. Flies were sleep deprived using the SNAP from zeitgeber time (ZT) 12 (beginning of the dark phase) to ZT0 (beginning of the light phase). Unless otherwise stated, at least 32 flies were analyzed for each experimental condition. Differences in sleep time were assessed using either a Student's t test or ANOVA which were followed by planned pairwise comparisons with a Tukey correction.

Locomotor rhythms.

Flies were individually placed into 5 × 65 mm tubes with regular food and placed into constant conditions for 10 d. Locomotor activity was continuously recorded in 30 min bins using the Trikinetics system. Locomotor rhythms were analyzed for 6 or 9 d using MATLAB-based computational tools designed by Joel Levine (Levine et al., 2002). Flies that did not show a significant peak on the periodogram were considered arrhythmic. At least 30 flies were analyzed for each genotype.

Falls.

Five flies aged 4–5 d and placed in 5 × 65 mm tubes were simultaneously observed by one experimenter during 30 min. Experimenters were blind to the condition. Data obtained with two different experimenters and two generations of ins-l flies were similar and pooled for the analysis.

Learning.

Learning was evaluated using aversive phototaxic suppression (APS) (Le Bourg and Buecher, 2002). Flies are individually tested in a T-maze where they are allowed to choose between a dark and a lighted vial. Adult flies are phototaxic and choose the lighted alley in the absence of reinforcer. During the test, a filter paper soaked with a quinine solution is placed in the lighted vial to provide an aversive association. In the course of 16 trials through the maze, flies learn to make more frequent choices to the dark vial (photonegative choices). The number of photonegative choices is tabulated during four successive blocks of four trials, and the performance score is the percentage of photonegative choices made in the last block of four trials. At least eight flies were evaluated for each condition. For each experiment, learning was evaluated by the same experimenter who was blind to genotype and condition. All flies were tested in the morning between ZT0 and ZT4. Flies were sleep deprived using the SNAP from ZT12 (beginning of the dark period) to ZT0 (beginning of the light period) and until each fly was tested for learning. Learning scores are normally distributed (Seugnet et al., 2008). Differences between scores were assessed using either a Student's t test or ANOVA which were followed by planned pairwise comparisons with a Tukey correction. Photosensitivity was evaluated using the T-maze with no filter paper. The average proportion of choices to the lighted vial during 10 trials was calculated for each individual fly. The phototaxis index (PI) is the average of the scores obtained for at least five flies ±SEM. Sensitivity to quinine/humidity was evaluated as in Le Bourg and C. Buecher (2002) with the following modifications: each fly was individually placed in a 14 cm transparent cylindrical tube covered with filter paper, uniformly lighted, and maintained horizontal. In one-half of the apparatus, the filter paper is soaked with quinine solution, whereas the other half is kept dry. The quinine/humidity sensitivity index [referred to as quinine sensitivity index (QSI)] was determined by calculating the time in seconds that the fly spent on the dry side of the tube when the other side had been wetted with quinine during a 5 min period.

Lifespan.

Three-day-old flies were individually placed into 5 × 65 mm tubes, and sleep was monitored until death. Food was replaced every 4 d. Three independent groups of 30 flies were analyzed for each genotype. Similar results were obtained by aging three groups of 10 flies in regular vials and visually monitoring dead flies every day.

Stress resistance.

Three-day-old flies were placed in 5 × 65 mm tubes for 2 baseline days and then placed in empty tubes (desiccation) or tubes with 1% agar (starvation) at ZT2, and locomotor activity was monitored until all flies died. Three independent groups of 30 flies were analyzed for each genotype.

Arousal.

To evaluate arousal during the day, Cs and ins-l flies were transferred in groups of 10 to an empty vial. All flies were awake both before and after the transfer. The vial was then subjected to a rapid shock to induce geotaxis. The percentage of flies present in the top half of a 50 ml tube was calculated after 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, and 120 s. To evaluate responsivity during the flies primary sleep period, we exposed Cs and ins-l flies to a 1 min pulse of light at ZT15; flies that were awake did not contribute to the score. The level of light was sufficiently strong to awaken all animals. The amount of sleep was then calculated for the following hour and expressed as a percentage of baseline sleep.

HPLC.

For each condition, independent sets of 20 fly heads (n = 4 replicates) were frozen and collected at age 5–6 d and at ZT0. Samples were sent to Dr. Raymond F. Johnson, Neurochemistry Core Laboratory, Nashville, TN, for HPLC analyses.

Lipid analysis.

Whole flies (10–15) were collected for each condition (ZT0). Samples were frozen at −80°C and homogenized in a 2:1 methanol:chloroform solution for lipid extraction. Lipid content was evaluated using colorimetric assays according to kit manufacturer's instructions. Triglycerides and cholesterol were evaluated with the Infinity kit (Thermo Electron), and nonesterified free fatty acids with the non-esterified fatty acids C kit (Wako). Lipid measurements were normalized to the initial weight of the flies (n = 3 replicates).

Quantitative PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from sets of 20 fly heads with Trizol (Invitrogen) and DNase I digested. cDNA synthesis was performed in quadruplicate using superscript III (Invitrogen), according to manufacturer protocol. To evaluate the efficiency of each reverse transcription, equal amounts of cDNA were used as a starting material to amplify RP49, a gene which expression is not changing during sleep deprivation (Shaw et al., 2002; Seugnet et al., 2008). cDNA from comparable reverse transcription reactions were pooled and used as a starting material to run four quantitative PCR (QPCR) replicates. Expression values for RP49 were used to normalize results between groups.

Microarray gene profiling.

Three groups of 20 short-sleeping ins-l flies (criteria, total daily sleep <60 min; daily sleep average, 16 ± 5 min) and three groups of Cs flies (daily sleep average, 725 ± 5 min) were collected at age 5–6 d. Total RNA was extracted from whole heads using the Trizol protocol (Invitrogen) and processed for cDNA synthesis and cRNA amplification according to the Affymetrix protocol. Over-represented gene ontology (GO) categories were identified using the GOToolBox software (Martin et al., 2004) with the hypergeometric statistical method. The following criteria were used to select over-represented GO categories shown in Figure 5 A: (1) a representation increased at least twofold in the experimental set compared with the reference; (2) at least 20 genes present in the given category in the experimental data set; and (3) over-represented with a p < 0.01 after false discovery rate correction.

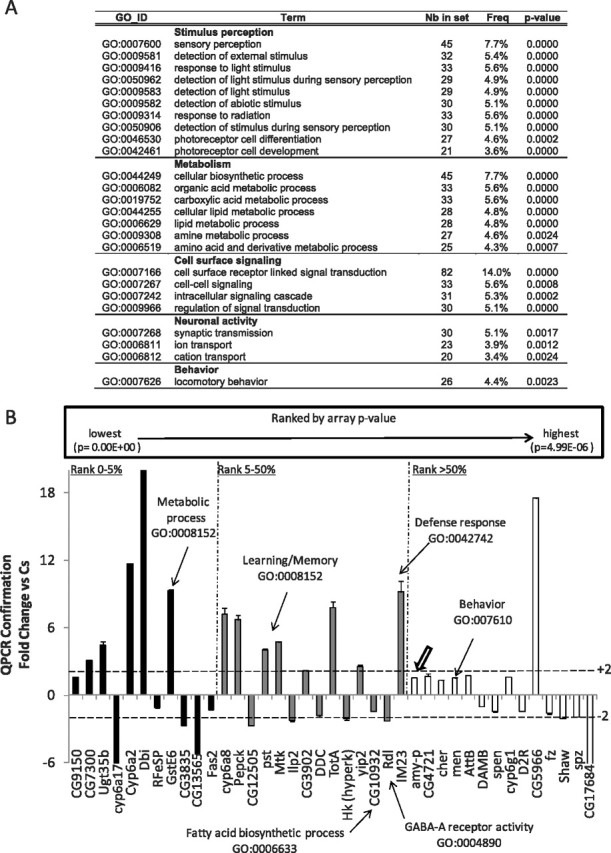

Figure 5.

Gene expression in ins-l flies. A, GO categories identified using GOToolBox software schematic. Note the overrepresentation of genes involved in sensory perception. Nb in set, Number of genes differentially expressed for the corresponding the GO category; Freq, number of genes with the corresponding GO annotation divided by the total number of GO-annotated genes differentially expressed. B, QPCR confirmation of gene expression changes in short-sleeping ins-l flies expressed as fold change from normal-sleeping Cs controls. RNA was collected from all flies after 3 h of spontaneous waking at ZT3. Genes were rank ordered by p value, and confirmation was conducted on the top 5% (black), 5–50% (gray), and bottom 50% (white) of all genes. Thick arrow indicates confirmation of Amylase expression. Error bars represent SEM.

Human samples.

Nine healthy human adult volunteers (seven men and two women) were enrolled in the study after providing their consent. The sleep protocol was performed at the Sleep Medicine Center, Department of Neurology, Washington University School of Medicine, and was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Washington University School of Medicine. The subjects were randomly separated in two groups, which where scheduled to alternate two weekends of either normal sleep or 28 h of continuous waking. On the normal-sleep weekend, the volunteers were allowed to fall asleep at 10:00 P.M. Normal sleep architecture was confirmed by standard polysomnography. The SD group remained awake and was allowed ad libitum access to water during the night. Saliva was collected from plain (noncitric acid) cotton Salivettes (Sarstedt), rapidly frozen over dry ice, and kept at −80°C until assayed. RNA was isolated from cell-free supernatant and processed for QPCR as described previously (Seugnet et al., 2006). Control experiments removing either mRNA or reverse transcriptase from the reaction failed to result in amplification (data not shown), indicating that the signal was mRNA and not attributable to contamination. Results were evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Results

Isolation of flies presenting insomnia-like traits using laboratory selection

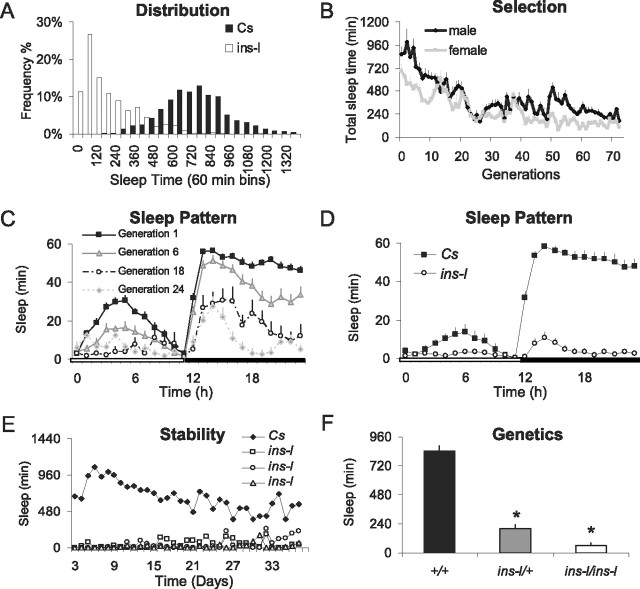

Evaluation of a normative dataset of wild-type Cs flies indicates that they display a sufficient range of sleep times and activity levels to make them suitable for laboratory selection (Fig. 1 A, black bars). In humans, insomnia starting earlier in life is believed to be under greater genetic influence than insomnia that is associated with aging (Watson et al., 2006). Thus, sleep was evaluated in 3-d-old male and female Cs flies for 4 d according to standard protocols (Shaw et al., 2000). For each generation, we identified 8–12 individual male and female flies that simultaneously demonstrated reduced sleep time in combination with increased sleep latency, reduced sleep bout duration, and elevated levels of waking activity (ins-l flies). These flies were then bred over successive generations. As seen in Figure 1, B and C, total sleep time was progressively reduced during selection and stabilized after ∼30 generations. Although sleep time was reduced both during the day and night, the increase in total wake time in selected flies came primarily at the expense of night time sleep (Fig. 1 C). Although total sleep time averaged 100 min or less by generation 65 (Fig. 1 D), ∼50% of ins-l flies obtained <60 min of sleep in a day. Moreover, the distribution of sleep times was shifted dramatically to the left (Fig. 1 A, white bars). Direct observation of 14 h of fly behavior revealed that all the ins-l flies were indeed awake and active with very few episodes of quiescence (see also supplemental Video1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material, for a comparison of ins-l and Cs flies).

Figure 1.

Sleep patterns of ins-l flies over generations. A, Frequency distribution of total sleep time in 60 min bins in wild-type Cs flies (n = 1000) and in ins-l flies at generation 65 (n = 364). B, Total sleep time in males (n = 40) and females (n = 40) for successive generations of ins-l flies. C, Daily sleep patterns (min/h) for progressive generations of ins-l flies (n ≈ 32/generation). D, Sleep in minutes per hour for 24 h in Cs (n = 32) and ins-l (generation 65; n = 32) flies. E, Daily total sleep time is shown for 37 d in one Cs and three ins-l flies. F, Daily total sleep time is decreased in ins-l/ins-l as well as in ins-l/Cs flies compared with Cs (ANOVA, F (1,89) = 5.50E + 06, p = < 0.0005). Error bars represent SEM.

In humans, primary insomnia is a chronic condition that may persist for 10 years (Janson et al., 2001). Thus, we evaluated sleep in ins-l flies over their lifespan. Sleep remains disturbed in ins-l flies over time (Fig. 1 E). Total sleep for three representative ins-l flies and one Cs fly are shown in Figure 1 E. These three ins-l flies obtained a total of 358 ± 128 min of sleep during their first 20 d of life versus 17,567 ± 655 min over the same time period in Cs flies. Importantly, the shortest-sleeping ins-l flies do not become longer sleepers or vice versa. To assay for dominant effects, we evaluated sleep in heterozygous ins-l/+ flies and found an intermediate sleep phenotype indicating the effects are semidominant (Fig. 1 F).

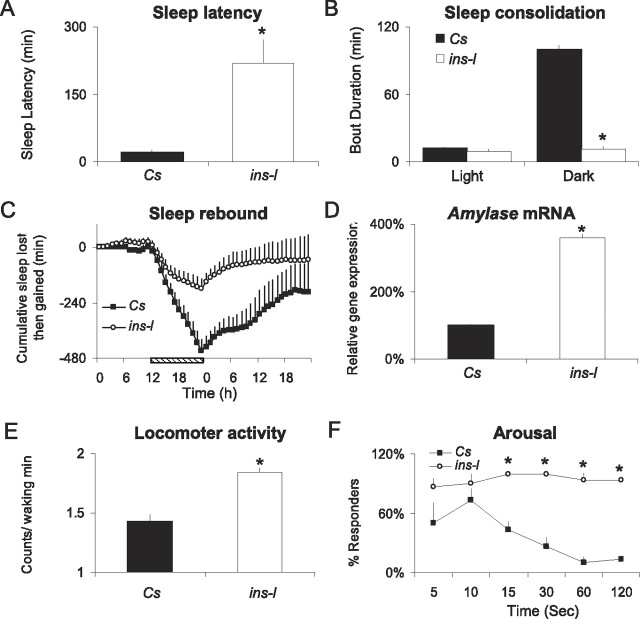

In addition to selecting for short-sleeping flies, we also selected for flies with an increased sleep latency, disrupted sleep consolidation, and hyperactivity. As seen in Figure 2 A, ins-l flies show increased latency from lights off to the first sleep bout of the night, suggesting that they have difficulty initiating sleep (Andretic and Shaw, 2005). ins-l flies also have difficulties maintaining sleep as evidenced by an inability to consolidate sleep into long bouts (Fig. 2 B, average sleep bout duration) (Andretic and Shaw, 2005). Indeed, the maximum episode of consolidated sleep that can be generated by an ins-l fly is only 36 ± 9 min versus 257 ± 22 min in Cs flies. Although ins-l flies exhibit fragmented sleep, they do not compensate by initiating more sleep episodes (6.8 ± 0.8 bouts vs 10.4 ± 0.2 bouts for ins-l and Cs flies, respectively). Since ins-l flies do not compensate by initiating more sleep episodes, it is possible that they are simply short-sleepers with a reduced need for sleep. Interestingly, ins-l flies exhibit a normal homeostatic response after 12 h of sleep deprivation, indicating that they are able to compensate for acute sleep loss (Fig. 2 C). However, human insomniacs also respond to acute sleep loss (Pigeon and Perlis, 2006), and thus, homeostasis cannot distinguish between short-sleep and insomnia. In humans, insomnia is associated with increased daytime sleepiness (Edinger et al., 2008). To determine whether ins-l flies also exhibit daytime sleepiness, we evaluated Amylase transcript levels using real-time QPCR. We have shown that, in flies, Amylase levels are only elevated after waking conditions that are associated with increased sleep drive and are not induced by stress (Seugnet et al., 2006). RNA was extracted from whole heads of Cs and ins-l flies that had been spontaneously awake for 3 h between ZT0 and ZT3. As seen in Figure 2 D, ins-l flies show elevated levels of Amylase mRNA relative to Cs flies, suggesting that they may experience increased sleep drive during their primary wake period.

Figure 2.

Characterization of insomnia-like traits. A, Sleep latency is increased in ins-l flies (n = 28) versus Cs flies (n = 33; *p = 8.78 × 10−8, one-tailed t test). B, Average sleep bout duration is reduced during the dark period in ins-l (n = 32) versus Cs (n = 32) flies; ANOVA F (1,122) = 4.34 × 104, p < 0.0005, *p < 0.05 planned comparison with Tukey correction). C, Cumulative sleep lost or gained during 12 h of sleep deprivation and subsequent recovery in ins-l (n = 32) and Cs (n = 32) flies; striped bar indicates sleep deprivation. For each hour, the amount of sleep obtained during baseline is subtracted from the respective amount of sleep time obtained during the corresponding hour of the sleep deprivation and recovery days; the difference scores are then summed across each hour to create the cumulated gained-lost plot. A negative slope indicates sleep lost, a positive slope indicates sleep gained; when the slope is zero, recovery is complete. D, Amylase mRNA levels are elevated in ins-l flies (percentage of Cs expression) at ZT0–1 (p = 0.0002, one-sample t test). E, Intensity of locomotor activity as measured by the counts/waking minutes for 24 h in Cs flies (n = 57) and ins-l flies (n = 61; *p = 1.67 × 10−10, two-tailed t test). F, Geotaxic response to a sudden shock is greater in ins-l versus Cs flies. Percentage of flies present in the top half of a 50 ml tube (responders). Three groups of 10 flies were tested for each genotype (genotype × time interaction, F (6,24) = 4.301, p = 0.0006). Error bars represent SEM.

As mentioned above, patients with insomnia are believed to be hyperaroused. Thus, we selected for flies with increased locomotor activity during waking. As seen in Figure 2 E, our selection procedure significantly increased the intensity of waking locomotor activity. The levels of activity during waking in ins-l flies are high during the day and during the night, and these levels are not statistically different (p = 0.56, paired t test). Insomniacs also show greater reactivity to stressors (Drake et al., 2008). To determine whether this would be true for ins-l flies as well, we exposed them to environmental perturbation during both the day and the night. As seen in Figure 2 F, ins-l flies are more responsive than Cs flies to mechanical stimulation during the day. ins-l flies are also more responsive to perturbations at night. When Cs and ins-l flies were exposed to a 1 min light pulse during their primary sleep period at ZT15, Cs flies briefly woke up in response to the light pulse but quickly went back to sleep (12.2 ± 9% of sleep lost during the following hour). In contrast, all the ins-l flies woke up and remained awake for an entire hour (100% of sleep lost, n = 16 flies per group, p < 0.05). Together, these data suggest that ins-l flies are in a state of increased arousal.

Physiological changes associated with the insomnia-like phenotype

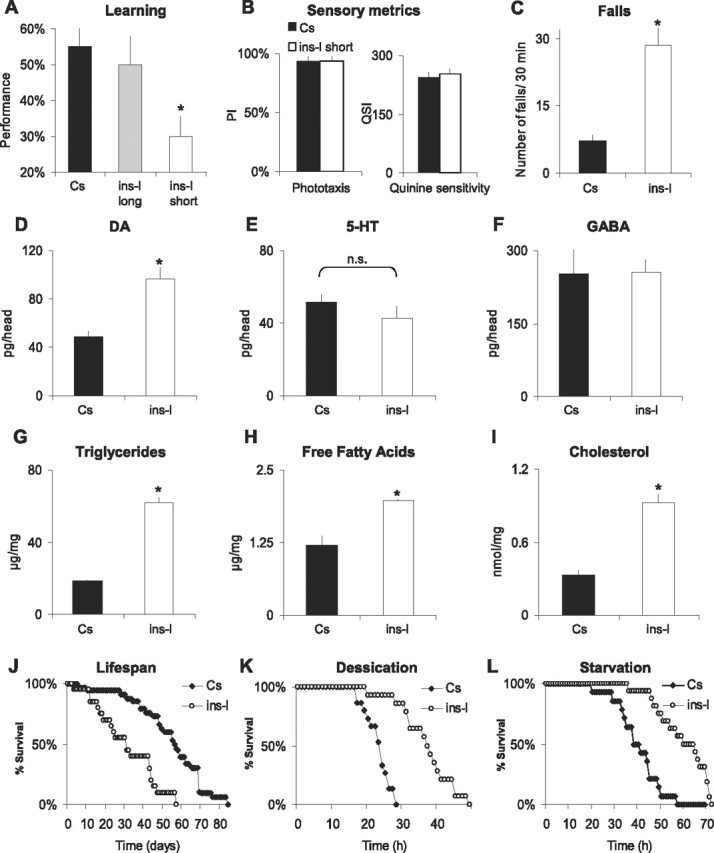

To be considered an insomniac, an individual must display daytime impairment or distress in combination with sleep disruption. Human insomniacs report that they have impaired concentration and poor memory (Orff et al., 2007). Thus, we evaluated learning in ins-l flies using APS (Le Bourg and Buecher, 2002). In this task, flies learn to avoid a light that is paired with an aversive stimulus (quinine/humidity). We have recently shown that APS is sensitive to both sleep loss and sleep fragmentation (Seugnet et al., 2008). As seen in Figure 3 A, learning is significantly impaired in the shortest-sleeping ins-lshort flies compared with Cs controls. To determine whether our selection protocol generated poor-learning flies as an independent phenotype from the observed sleep deficit, we evaluated learning in long-sleeping ins-l flies (ins-llong) (Fig. 1 A). Importantly, longer-sleeping siblings maintain their ability to learn, indicating that our selection procedure did not inadvertently create a poor-learning fly. The time to complete the test, photosensitivity, and quinine sensitivity (control metrics) were similar in Cs, ins-lshort, and ins-llong flies, indicating that the learning deficit was not attributable to differences in sensory thresholds (Fig. 3 B; supplemental Table 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material).

Figure 3.

Physiological changes associated with the insomnia-like phenotype. A, Learning in Cs flies, longer-sleeping ins-l flies (average daily sleep time, 347 ± 55 min), and short-sleeping ins-l flies (average daily sleep, 26 ± 7 min; n = 10 for each group; *ANOVA, F (1,27) = 10.26, p = 0.0005, *p < 0.05, planned comparison with Tukey correction). B, PI and QSI in Cs flies (n = 5) and short-sleeping ins-l flies (n = 5). C, Number of falls during 30 min in Cs (n = 20) and ins-l flies (n = 18; *p < 0.0001, two-tailed t test). D–F, Head neurotransmitter levels in Cs and ins-l flies, as measured by HPLC (n = 4 replicates of 20 heads; *p = 0.02, two-tailed t test). G–I, Whole-body lipid content in Cs and ins-l flies (n = 3 replicates of 10 flies): triglycerides (G), free fatty acids (H), and cholesterol (I) [*p = 0.0001 (G), p = 0.002 (H), p = 0.01 (I), two-tailed t test]. J, Representative survival curve of aging ins-l compared with Cs flies (30 flies/group). K, L, Representative survival curves of ins-l and Cs flies after exposure to desiccation (K) or starvation (L) (30 flies/group). D, Error bars represent SEM.

In addition to cognitive impairments, human insomniacs exhibit deficits in motor coordination as indicated by difficulty in maintaining their balance (Hauri, 1997). Thus, we evaluated the number of spontaneous falls in young age-matched Cs and ins-l flies walking for 30 min in an obstacle-free environment. Cs flies rarely fall under these conditions. In contrast, ins-l flies frequently lose their balance (Fig. 3 C). Given the role of dopamine in learning and motor control, we evaluated transmitter levels in whole heads of ins-l flies. As seen in Figure 3 D, dopamine levels are significantly elevated in ins-l flies (Fig. 3 D). Dopamine is present in the brain as well as in peripheral tissues such as the epidermis where it affects pigmentation. However, no obvious change in cuticle pigmentation is observed in ins-l flies. Thus, the large increase in dopamine level seen in ins-l flies most likely reflects a significant change of the neurotransmitter in the brain. Interestingly, we found that learning impairments after acute sleep deprivation are also associated with an increase in dopamine levels (Seugnet et al., 2008). Levels of 5-HT and GABA, which are also associated with learning and sleep disruption, were not changed (Fig. 3 E,F). Together, these results further implicate dopamine signaling in cognitive impairments after sleep disruption.

Accumulating evidence in humans indicates that sleep disruption may increase the risk of obesity (Knutson and Van Cauter, 2008). Moreover, insomnia is more frequent in obese than nonobese individuals (Janson et al., 2001), and common genetic effects have been observed between insomnia and obesity in a recent twin study (Watson et al., 2006). Thus, we evaluated organismal levels of triglycerides, free fatty acids, and cholesterol in ins-l flies. As with humans, ins-l flies exhibit increased adiposity (Fig. 3 G–I). These data further suggest that ins-l flies are getting less sleep than they need and are not simply short sleepers.

Several recent epidemiological studies have found that sleep duration and insomnia are associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality and reduced lifespan (Tamakoshi and Ohno, 2004). Reduced sleep has also been associated with shortened lifespan in Drosophila (Cirelli et al., 2005; Pitman et al., 2006; Koh et al., 2008). If our selected lines are getting less sleep than they need, one would predict that they would have a shortened lifespan. As seen in Figure 3 J, this is indeed the case. The reduced lifespan observed in our ins-l flies may be attributable to reduced sleep or decreased fitness resulting from inbreeding. To determine whether our ins-l flies exhibited reduced fitness, we exposed them to starvation, desiccation, and paraquat (Fig. 3 K,L, paraquat data not shown). Survival curves clearly indicate that ins-l flies do not exhibit reduced fitness when compared with Cs controls. In addition, ins-l flies have no discernable morphological, developmental, or fertility phenotypes, further indicating that they do not exhibit reduced fitness.

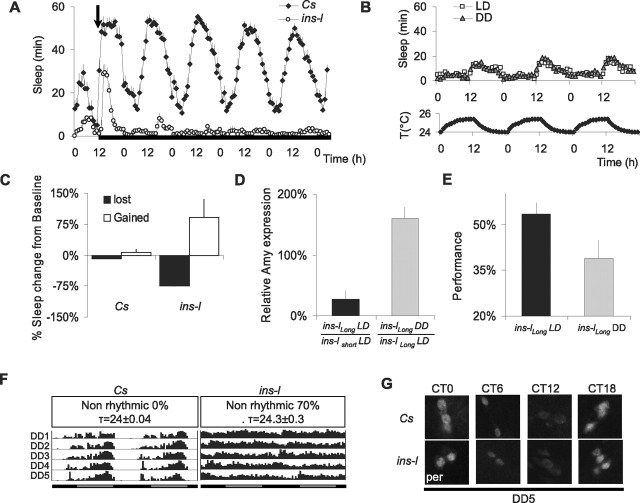

Sleep in the absence of zeitgebers

The misalignment of sleep and circadian cycles can trigger or aggravate insomnia symptoms in humans (e.g., jet lag). To assess the influence of zeitgebers, we evaluated sleep in ins-l flies placed into constant darkness (DD). When zeitgebers are removed, ins-l flies show a further decrease in sleep time (Fig. 4 A, white circles), a result not observed in Cs flies (Fig. 4 A, black diamonds). To determine whether the increased wakefulness was attributable to the absence of light, we placed ins-l flies in constant darkness but allowed temperature to maintain a circadian oscillation of ±1.0°C. ins-l flies were able to entrain to these small circadian fluctuations in temperature, and sleep was not altered compared with LD (Fig. 4 B). To further evaluate the consequences of sleep loss induced by removing zeitgebers, we evaluated the behavior of longer-sleeping ins-l flies. Longer-sleeping ins-l flies were examined to ensure that all flies would have the opportunity to lose sleep when placed into DD. Moreover, since the shortest-sleeping ins-l flies cannot learn, it is not possible to assess whether additional sleep disruption alters cognitive behavior. As seen in Figure 4 C, ins-l flies not only lose sleep when placed into DD for 24 h, they initiate a homeostatic response when placed back into LD. In comparison, Cs flies only lose 7 ± 1% of their baseline sleep in DD. Interestingly, Amylase mRNA levels are lower in ins-llong flies compared with their short-sleeping siblings when maintained in LD, suggesting that they experience lower sleep drive (Fig. 4 D, left). However, when sleep is disrupted by placing ins-llong flies into DD Amylase, mRNA levels increase in comparison with control ins-llong siblings maintained under LD (Fig. 4 D, right). Given the mild-nature of placing flies into constant darkness, these data are consistent with our previous results, demonstrating that, in flies, Amylase levels are responsive to conditions of high sleep drive, do not depend on the method used to keep the animal awake, and are not simply activated by stress. To determine whether waking induced by removing zeitgebers was associated with learning impairments, we evaluated ins-llong flies under LD and after 5 d in DD. As seen in Figure 4 E, ins-llong flies learn normally under LD but are significantly impaired after the additional sleep disruption induced by removing zeitgebers; learning impairments were not associated with changes in control metrics (supplemental Table 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material), and 5 d of DD does not alter learning in Cs flies (data not shown). Thus, the absence of zeitgebers appears to interfere with the ability to obtain needed sleep in ins-l flies.

Figure 4.

Sleep in the absence of zeitgebers. A, Baseline sleep in minutes per hour in Cs and ins-l flies maintained under LD and after placement into DD (arrow). Black rectangle indicates lights off. B, Top graph, Sleep in minutes per hour in ins-l flies maintained in LD or in DD. Bottom graph, Circadian oscillations in temperature used to entrain the flies in DD. C, Sleep was evaluated in Cs and ins-l flies placed into DD for 24 h (black bars) and then into LD for recovery (white bars). Sleep is expressed as a percentage of baseline sleep in LD. D, Amylase levels in ins-llong flies under LD (n = 20) and after 24 h in DD (n = 20); data are presented as percentage change from age-matched ins-lshort and ins-llong flies, respectively (*p < 0.05, two-tailed t test). E, Learning in ins-llong flies in LD (average daily sleep 331 ± 19 min) and after 5 d in DD (average daily sleep at DD5, 72 ± 14 min; n = 10/group; *p = 0.036, one-tailed t test). F, Representative actograms for single female flies from DD1 to DD5 are shown. Similar results were obtained with ins-l males. G, Immunolocalization of PER protein in the sLNvs at DD5 (single confocal sections are shown). Ten brains were evaluated for each time point; a representative example is shown. Error bars represent SEM.

Is sleep loss in DD associated with a deficit in the circadian pacemaker? Seventy percent of ins-l flies appear to lose locomotor rhythms in constant conditions, whereas the remaining cycling flies have a normal 24 h period (Fig. 4 F). The average rhythmicity index (RI) was 0.10 ± 0.02 for ins-l flies for 9 d in DD, compared with 0.43 ± 0.03 for Cs flies. We found that RI was not correlated with either counts/waking minutes (r = 0.04, n = 30) or the amount locomotor activity (r = −0.2, n = 30). In Drosophila, circadian rhythms in DD are controlled by a subset of clock neurons, the small ventral lateral neurons (sLNvs). In ins-l flies, sLNvs neurons still display circadian oscillations of the Period (PER) protein, similar to Cs flies (Fig. 4 G). Normal circadian oscillations of the TIMELESS (TIM) protein were also observed in the sLNvs of ins-l flies: TIM was detected in the cytoplasm at CT18, in the nucleus at CT0, and was not detected at CT6 and CT12 (data not shown). These results suggest that the sleep reduction and loss of rhythmicity observed in ins-l flies in constant conditions is not merely linked to a deficit of the core molecular clock.

Gene profiling of ins-l flies

By using laboratory selection, we generated a line of flies that exhibit a constellation of unique phenotypes that may be useful for both elucidating molecular mechanisms important for aspects of sleep regulation and that may provide insights into both the causes and long-term consequences of insomnia. However, if the behavioral changes seen in ins-l flies are caused by changes in many genes, as is the case for other complex traits, it may not be possible to easily map them using classic genetic strategies. Moreover, since polymorphisms in regulatory regions alter expression levels without disrupting gene function (Mackay, 2004), sequencing strategies may also prove ineffective. Thus, we conducted whole-genome transcript profiling using Affymetrix high density oligonucleotide microarrays to identify genes that are modified in ins-l flies. To maximize the comparison between ins-l and Cs flies and to reduce variability, we monitored sleep for 3 d and identified individuals that displayed stable sleep patterns. Only those ins-l flies that slept <60 min a day for each of the 3 d were included in the study (average daily sleep, 16 ± 5 min). Cs flies display a large range of sleep times (Fig. 1 A). To avoid combining Cs flies with short, fragmented sleep or flies that displayed excessively long sleep and thus might be unhealthy together with normal-sleeping healthy flies, we identified individuals whose total sleep fell at the center of the distribution of daily sleep (average daily sleep, 721 ± 5 min). Sleep was evaluated in three independent groups of ins-l and Cs flies on separate days. RNA was collected from whole heads of flies that had been spontaneously awake for 3 h at CT3; 3 h of spontaneous waking is sufficient to change gene expression in rodents and flies (Shaw et al., 2000; Cirelli et al., 2004). Statistical differences were identified first using the Cyber-T Bayesian statistical framework followed by Bonferroni correction (http://cybert.microarray.ics.uci.edu/) (Baldi and Long, 2001). In addition, the data were independently analyzed using Partek Genomics Suite with a false discovery rate test correction set to p < 0.01 (Partek). Only those genes that were identified as being significant using both Cyber-T and Partek were considered further. Approximately 1350 genes are differentially expressed in ins-l flies, 755 of which were found to have homology with human genes using the Genomic Information for Eukaryotic Organisms Database (www.eugenes.org). The mean, SEM, fold change, and both the corrected and noncorrected p values for all 1350 genes can be found in supplemental Table 2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material.

To further evaluate the 1350 genes that were differentially expressed between Cs and ins-l flies, we conducted a GO analysis using GOToolBox software (Martin et al., 2004) with the hypergeometric statistical method followed by false discovery rate correction. As seen in Figure 5 A, over-represented GO categories include metabolism, neuronal activity, behavior and sensory perception. Changes in genes associated with lipid metabolism and synapse transmission are consistent with the increased adiposity and learning deficits observed in ins-l flies. Importantly, the overrepresentation of genes associated with sensory perception suggest the possibility that hyperarousal in insomniacs may be attributable to increased activity within sensory systems and that these processes may be under genetic control.

The genes listed in supplemental Table 2, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material, were identified from three experimental replicates collected on separate days. Given that the expression data were further analyzed using two independent statistical approaches with extremely conservative adjustments for multiple tests, we believe the results to be reliable. Nonetheless, we collected a fourth independent replicate of the shortest-sleeping ins-l flies and normal-sleeping Cs flies for confirmation using QPCR. As above, flies were monitored for 3 d to ensure that sleep was stable, and the flies were collected at ZT3. Genes were rank ordered by p value and QPCR confirmation was conducted on candidate genes that fell within the top 0–5%, 5–50%, and bottom 50% of all genes. As seen in Figure 5 B, we successfully confirmed expression changes across all levels of significance, providing further validation that the identified genes are modified in ins-l flies.

If these genes are associated with the insomnia phenotypes, their expression should persist even when ins-l flies are placed into a different genetic background. Although we do not yet have a genetic marker for the ins-l flies, our results indicate that ins-l is dominant (Fig. 1 F). Thus, ins-l flies were out-crossed to normally sleeping w1118 flies. After each cross, white-eyed progeny that displayed short-sleep, short-sleep bouts, and hyperactivity were identified and then crossed again to normal-sleeping w1118 flies. This was repeated five times, creating a new stock, ins-lw. ins-lw flies were then divided into two groups and selected again for 20 generations: one group was reselected to amplify insomnia-like phenotypes, whereas the other was back-selected to obtain normal-sleeping flies (nsw flies) (supplemental Fig. 1, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material). Sleep time was modestly increased in ins-lw flies immediately after the outcross but returned to typical ins-l levels within three rounds of selection and remained stable thereafter, indicating that the critical loci were maintained in this new line (data not shown). Importantly, ins-lw flies exhibited all of the phenotypes found in ins-l flies. After the reselection, we performed real-time QPCR on head RNA extracts obtained from ins-lw and normal-sleeping nsw flies for a subset of the genes shown in Figure 5 B. As above, flies were monitored for 3 d to ensure sleep stability, and RNA was collected at CT3. As seen in supplemental Figure 1B, available at www.jneurosci.org as supplemental material, the expression changes seen in ins-lw versus nsw are similar to that observed in ins-l versus Cs flies. Thus, genes associated with insomnia can be identified in at least two different genetic backgrounds.

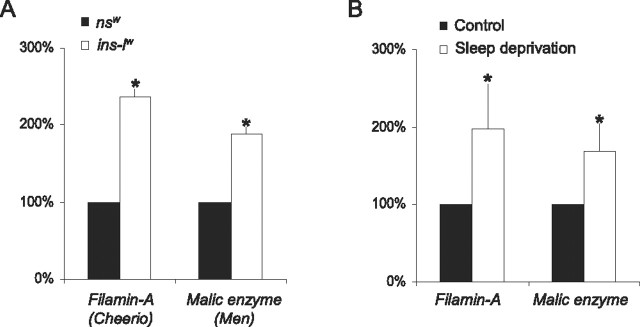

Genes differentially regulated ins-l flies are modulated by sleep loss in humans

An important issue about Drosophila sleep research is whether it has relevance for human sleep research. We have previously shown that Amylase, a biomarker of sleepiness in Drosophila, is upregulated in human saliva after sleep loss (Seugnet et al., 2006). Amylase is not responsive to stress in flies and is only transiently elevated by stress in humans (Takai et al., 2004; Seugnet et al., 2006; Schoofs et al., 2008). Importantly, we demonstrated that Amylase levels were elevated after 28 h but not 24 h of waking in humans, whereas cortisol levels remained unchanged (Seugnet et al., 2006). Thus, it is possible to identify genes in human saliva that are responsive to sleep loss. Saliva contains thousands of mRNAs, and recent studies have demonstrated that they can be used as diagnostic markers for human diseases (Palanisamy et al., 2008). To determine whether genes identified in ins-l flies could be modified by sleep disruption in humans; we designed primers for the human homologues of six genes differentially expressed in ins-l flies. Of these six genes, only two, malic enzyme (homolog of Drosophila men) and Filamin A (homolog of Drosophila cheerio), are reliably detected by QPCR in saliva RNA extracts. men and cheerio have elevated mRNA levels in ins-l flies (Fig. 6 A). Interestingly, their human homologues are upregulated in normal subjects after 28 h of waking, indicating that both genes are modulated by sleep loss in humans and flies (Fig. 6 B).

Figure 6.

Genes differentially regulated ins-l flies are modulated by sleep loss in humans. A, Filamin-A (Cheerio) and Malic enzyme (Men) are both upregulated in ins-lw flies compared with nsw flies. QPCR data from 20 fly heads collected at ZT0. Levels are expressed as percentage of nsw expression. B, Filamin-A and Malic enzyme expressions are elevated after 28 h of waking in humans (n = 8; Wilcoxon signed rank test, p = 0.02 and p = 0.059, respectively). QPCR data obtained from saliva mRNA extracts. Each saliva sample collected after sleep deprivation was compared with a circadian matched baseline sample from the same subject. Levels are expressed as percentage of baseline expression. Error bars represent SEM.

Discussion

Using artificial selection, we have generated a unique line of flies that exhibit a constellation of stable and heritable phenotypes that are directly relevant for addressing fundamental questions about sleep regulation. These flies display large disruptions in sleep and as a consequence can be useful in identifying basic mechanisms of sleep regulation. Importantly, the sleep deficits observed in ins-l flies are not produced by mechanical interventions. Thus, these flies are well suited to evaluate the acute and long-term consequences of sleep disruption at all levels of investigation, including genetic, circuit, physiologic, and behavioral analyses. Our exhaustive characterization of ins-l flies indicates that they may be particularly useful for providing additional insight into mechanisms linking sleep with important physiological processes underlying metabolism, learning, and aging.

An additional and important feature of the ins-l flies is that the changes in behavior are unlikely to be caused by changes in a single gene. The fact that 30 generations were necessary to reach a plateau in the selection process suggests that a large number of genes are involved in the ins-l phenotype. Interestingly, a similar number of generations (20–30) allowed the progressive selection of other complex behaviors such as learning (Mery and Kawecki, 2002), locomotion (Jordan et al., 2007), or aggression (Dierick and Greenspan, 2006). In addition, we selected for multiple phenotypes, each of which exhibited slow incremental changes over the course of many generations. Thus, it is unlikely that we inadvertently selected for a mutation at a single locus. Rather, the ins-l phenotypes are undoubtedly a consequence of individuals inheriting many alleles which exert small but cumulative effects on sleep regulatory circuits (Mackay et al., 2005). This interpretation is consistent with the observation that it is rare for sleep disorders to be attributed to single gene defects (Tafti et al., 2005). Thus, ins-l flies more closely approximate conditions found in human populations, further increasing the utility of these animals for the efficient dissection of sleep regulation.

We chose to create an animal model of insomnia based on our hypothesis that sleep disorders are highly prevalent in general populations because of the inherent complexity of sleep regulation. Insomnia is among the most common of all sleep disorders. As a complaint, insomnia occurs in 30–50% of the population annually; when accompanied by daytime impairment, insomnia afflicts 9–15% of the population, and when diagnosed using DSM-IV criteria, the prevalence is 6% (Ohayon, 2002). Twin studies suggest that genetics may account for approximately one-third of the variance in insomnia complaints (Heath et al., 1990; Watson et al., 2006). If insomnia results, in part, from predisposing trait characteristics, it should be possible to amplify these traits using laboratory selection. Insomnia is defined as difficulty falling asleep, difficulty staying asleep, or poor sleep quality which is accompanied by daytime impairment or distress (Edinger et al., 2004). Moreover, patients with insomnia are hyperaroused and show greater reactivity to stressors than good sleepers (Perlis et al., 2001; Bastien et al., 2008). With this in mind, we used artificial selection to generate flies with insomnia-like traits. Our selection created flies with a tenfold reduction in sleep time. In addition, these flies exhibited (1) difficulty in initiating sleep as defined by increased sleep latency; (2) difficulties in maintaining sleep as indicated by an inability to maintain normal length sleep bouts; (3) hyperarousal, as measured by both an increase in locomotor activity during waking and increased responsivity to environmental perturbations; (4) reduced lifespan; (5) decreased cognitive performance during the day; (6) evidence for increased sleep drive during the animals' primary wake period; and (7) difficulty sleeping after abrupt changes to environmental zeitgebers. To our knowledge, this is the first animal model of insomnia to result in such large, stable, and heritable disruptions in sleep regulation that are not brought about by experimentally induced stress.

Recently, several labs have used artificial selection coupled with whole-genome arrays as an efficient strategy to identify genes that underlie complex behavior (Dierick and Greenspan, 2006; Edwards et al., 2006; Jordan et al., 2007; Sørensen et al., 2007; Zhou et al., 2007). Follow-up studies using single gene mutations were then evaluated to demonstrate that the identified gene modified the behavior of interest in an otherwise wild-type background. One reason that no attempt was made to use genetic tools to rescue the phenotypes observed in the selected lines is that the behavior observed in these selected lines is likely attributable to small changes in many genes. As a consequence, modifying a change in a single gene may not result in a large change in the behavior in the selected lines. Thus, no gene has yet been shown to be causally involved in producing the behavioral phenotype in the selected flies themselves. Of course the goal of the selection strategy is to find genes whose function can be generalized beyond an isolated and rare genetic line of flies. In that regard, artificial selection combined with whole-genome gene profiling has successfully identified candidate genes, many of which have been shown to alter behavior using genetic strategies.

Using whole-genome arrays, we identified 1350 genes that are differentially expressed in ins-l flies compared with their genetic controls. The changes in gene expression are robust and were observed even when ins-l was placed into a separate genetic background. ins-l flies are dominant, and thus, we were able to follow specific insomnia-like traits over multiple crosses. The new line, ins-lw, displays all of the characteristic traits found in ins-l flies, including those that were not actively selected during the outcross, such as an inability to sleep after the removal of zeitgebers. The observation that two genes, which were identified in ins-l flies, are also responsive to acute sleep deprivation in humans increases our confidence that the genes identified in the microarrays are robust and useful for investigating genes involved in sleep regulation.

It is important to acknowledge that all gene profiling experiments are correlation in nature and thus identify genes that are causative for a given behavior and those that are consequence of the behavioral change (Robinson et al., 2005). Thus, for each gene identified by transcriptional gene profiling, genetic experiments are required to determine whether the gene activation/inactivation reveals a pathway that regulates sleep, that is regulated by sleep, or that is part of a compensatory mechanism for sleep loss. This latter distinction is particularly relevant for the ins-l flies. That is, although they display substantial reduction in sleep in combination with cognitive impairments, increased adiposity, and reduced lifespan, ins-l flies also show signs of resistance to the deleterious effects of waking. For example, a substantial number of ins-l flies are able to remain continuously awake for several days without dying or showing overt signs of sickness. Interestingly, the longest-sleeping ins-l flies retain many insomnia-like traits, including severely fragmented sleep. Nonetheless, they retain their ability to learn in the face of this challenge, whereas Cs flies with similarly fragmented sleep are learning impaired (Seugnet et al., 2008). Although the changes in learning may appear to be minor, they are well within the range of effect sizes observed after sleep loss in humans and rodents across a number of cognitive domains (Graves et al., 2003; Frey et al., 2004; Fu et al., 2007; Piérard et al., 2007). Together, these data suggest that both sleep disruption and resilience to sleep loss are components of the genetic condition and are likely to be reflected in gene expression changes.

Although we have identified a large number of candidate genes, our extensive phenotypic characterization of ins-l flies directs us toward specific classes of genes and neuronal circuits. For example, one of the most highly over-represented category of genes that are differentially modulated in ins-l flies is those involved in sensory perception. Thus, the increased amount of waking that is observed in ins-l flies may be due, in part, to the continued activity of specific sensory networks during sleep. In that regard, it is interesting to note that human insomniac patients have also been hypothesized to display persistent sensory processing during sleep as indicated by increased metabolism in the thalamus (Nofzinger et al., 2004; Desseilles et al., 2008).

Given the established role of sleep in synaptic plasticity and the learning deficits observed in ins-l flies, it is perhaps not surprising to find that another large class of over-represented genes in ins-l flies is involved in cell surface signaling (80 genes) or synaptic transmission (30 genes). Interestingly, human insomniacs show deficits in specific brain structures involved in memory and behavioral flexibility (Nofzinger et al., 2004; Riemann et al., 2007). Similarly, specific structures involved in learning and memory, such as dopaminergic neurons or the mushroom bodies (MBs), may play a key role in the deficit observed in ins-l flies. MBs regulate total sleep time and play an important role in protecting flies from learning deficits after sleep deprivation (Joiner et al., 2006; Pitman et al., 2006; Seugnet et al., 2008). Thus, the MBs are likely to play an important yet complex role in the circuitry underlying insomnia. Finally, ins-l flies lose their ability to sleep after the removal of zeitgebers, suggesting that aspects of insomnia might involve specific subsets of clock neurons. Recent studies have found that artificially increasing the electrical excitability of large ventral lateral neurons, which are responsive to light, increases waking (Parisky et al., 2008; Shang et al., 2008; Sheeba et al., 2008). Although it is not clear whether more physiologic manipulations will produce similar results, genes affecting this circuitry are of particular interest. Our data suggest that a gene can play multiple roles in the brain, thereby producing an individual that exhibits evidence of both sleep disruption and resilience to sleep loss. Identifying genes that confer resilience may provide crucial insight into mechanisms of sleep regulation.

Footnotes

This study was funded in part by National Institutes of Health Grants 1 R01 NS051305-01A1 and 5 K07 AG21164-02, the McDonnell Center for Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, and the National Institutes of Health Neuroscience Blueprint Core Grant (NS057105). We thank Isabelle Raymond Shaw and Anne Germaine for helpful comments. L.S. designed the research, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote this manuscript; Y.S., L.G., S.I.G., and S.P.D. all performed research. M.T. performed research and wrote this manuscript. P.J.S. designed the research, performed research, analyzed data, and wrote this manuscript. All authors commented on this manuscript.

References

- Allada R, Siegel JM. Unearthing the phylogenetic roots of sleep. Curr Biol. 2008;18:R670–R679. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andretic R, Shaw PJ. Essentials of sleep recordings in Drosophila: moving beyond sleep time. Methods Enzymol. 2005;393:759–772. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)93040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldi P, Long AD. A Bayesian framework for the analysis of microarray expression data: regularized t-test and statistical inferences of gene changes. Bioinformatics. 2001;17:509–519. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.6.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastien CH, St-Jean G, Morin CM, Turcotte I, Carrier J. Chronic psychophysiological insomnia: hyperarousal and/or inhibition deficits? An ERPs investigation. Sleep. 2008;31:887–898. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.6.887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borbély AA, Tobler I. Endogenous sleep-promoting substances and sleep regulation. Physiol Rev. 1989;69:605–670. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1989.69.2.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli C, Gutierrez CM, Tononi G. Extensive and divergent effects of sleep and wakefulness on brain gene expression. Neuron. 2004;41:35–43. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00814-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirelli C, Bushey D, Hill S, Huber R, Kreber R, Ganetzky B, Tononi G. Reduced sleep in Drosophila Shaker mutants. Nature. 2005;434:1087–1092. doi: 10.1038/nature03486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desseilles M, Dang-Vu T, Schabus M, Sterpenich V, Maquet P, Schwartz S. Neuroimaging insights into the pathophysiology of sleep disorders. Sleep. 2008;31:777–794. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.6.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dierick HA, Greenspan RJ. Molecular analysis of flies selected for aggressive behavior. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1023–1031. doi: 10.1038/ng1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake CL, Scofield H, Roth T. Vulnerability to insomnia: the role of familial aggregation. Sleep Med. 2008;9:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edinger JD, Bonnet MH, Bootzin RR, Doghramji K, Dorsey CM, Espie CA, Jamieson AO, McCall WV, Morin CM, Stepanski EJ. Derivation of research diagnostic criteria for insomnia: report of an American Academy of Sleep Medicine Work Group. Sleep. 2004;27:1567–1596. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.8.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edinger JD, Means MK, Carney CE, Krystal AD. Psychomotor performance deficits and their relation to prior nights' sleep among individuals with primary insomnia. Sleep. 2008;31:599–607. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.5.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards AC, Rollmann SM, Morgan TJ, Mackay TF. Quantitative genomics of aggressive behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltenyi K, Greenspan RJ, Newport JW. Activation of EGFR and ERK by rhomboid signaling regulates the consolidation and maintenance of sleep in Drosophila . Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1160–1167. doi: 10.1038/nn1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey DJ, Badia P, Wright KP., Jr Inter- and intra-individual variability in performance near the circadian nadir during sleep deprivation. J Sleep Res. 2004;13:305–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2004.00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu J, Li P, Ouyang X, Gu C, Song Z, Gao J, Han L, Feng S, Tian S, Hu B. Rapid eye movement sleep deprivation selectively impairs recall of fear extinction in hippocampus-independent tasks in rats. Neuroscience. 2007;144:1186–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graves LA, Heller EA, Pack AI, Abel T. Sleep deprivation selectively impairs memory consolidation for contextual fear conditioning. Learn Mem. 2003;10:168–176. doi: 10.1101/lm.48803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauri PJ. Cognitive deficits in insomnia patients. Acta Neurol Belg. 1997;97:113–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath AC, Kendler KS, Eaves LJ, Martin NG. Evidence for genetic influences on sleep disturbance and sleep pattern in twins. Sleep. 1990;13:318–335. doi: 10.1093/sleep/13.4.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janson C, Lindberg E, Gislason T, Elmasry A, Boman G. Insomnia in men-a 10-year prospective population based study. Sleep. 2001;24:425–430. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.4.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner WJ, Crocker A, White BH, Sehgal A. Sleep in Drosophila is regulated by adult mushroom bodies. Nature. 2006;441:757–760. doi: 10.1038/nature04811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan KW, Carbone MA, Yamamoto A, Morgan TJ, Mackay TF. Quantitative genomics of locomotor behavior in Drosophila melanogaster. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R172. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutson KL, Van Cauter E. Associations between sleep loss and increased risk of obesity and diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1129:287–304. doi: 10.1196/annals.1417.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh K, Joiner WJ, Wu MN, Yue Z, Smith CJ, Sehgal A. Identification of SLEEPLESS, a sleep-promoting factor. Science. 2008;321:372–376. doi: 10.1126/science.1155942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kume K, Kume S, Park SK, Hirsh J, Jackson FR. Dopamine is a regulator of arousal in the fruit fly. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7377–7384. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2048-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Bourg E, Buecher C. Learned suppression of photopositive tendencies in Drosophila melanogaster. Anim Learn Behav. 2002;30:330–341. doi: 10.3758/bf03195958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine JD, Funes P, Dowse HB, Hall JC. Signal analysis of behavioral and molecular cycles. BMC Neurosci. 2002;3:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay TF. The genetic architecture of quantitative traits: lessons from Drosophila . Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2004;14:253–257. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackay TF, Heinsohn SL, Lyman RF, Moehring AJ, Morgan TJ, Rollmann SM. Genetics and genomics of Drosophila mating behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(Suppl 1):6622–6629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501986102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D, Brun C, Remy E, Mouren P, Thieffry D, Jacq B. GOToolBox: functional analysis of gene datasets based on Gene Ontology. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R101. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-12-r101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mery F, Kawecki TJ. Experimental evolution of learning ability in fruit flies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14274–14279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222371199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nofzinger EA, Buysse DJ, Germain A, Price JC, Miewald JM, Kupfer DJ. Functional neuroimaging evidence for hyperarousal in insomnia. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2126–2128. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obal F, Jr, Krueger JM. Biochemical regulation of non-rapid-eye-movement sleep. Front Biosci. 2003;8:d520–d550. doi: 10.2741/1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:97–111. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orff HJ, Drummond SP, Nowakowski S, Perils ML. Discrepancy between subjective symptomatology and objective neuropsychological performance in insomnia. Sleep. 2007;30:1205–1211. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.9.1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palanisamy V, Park NJ, Wang J, Wong DT. AUF1 and HuR proteins stabilize interleukin-8 mRNA in human saliva. J Dent Res. 2008;87:772–776. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisky KM, Agosto J, Pulver SR, Shang Y, Kuklin E, Hodge JJ, Kang K, Kang K, Liu X, Garrity PA, Rosbash M, Griffith LC. PDF cells are a GABA-responsive wake-promoting component of the Drosophila sleep circuit. Neuron. 2008;60:672–682. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlis ML, Merica H, Smith MT, Giles DE. Beta EEG activity and insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2001;5:363–374. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piérard C, Liscia P, Philippin JN, Mons N, Lafon T, Chauveau F, Van Beers P, Drouet I, Serra A, Jouanin JC, Béracochéa D. Modafinil restores memory performance and neural activity impaired by sleep deprivation in mice. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;88:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2007.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pigeon WR, Perlis ML. Sleep homeostasis in primary insomnia. Sleep Med Rev. 2006;10:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitman JL, McGill JJ, Keegan KP, Allada R. A dynamic role for the mushroom bodies in promoting sleep in Drosophila . Nature. 2006;441:753–756. doi: 10.1038/nature04739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riemann D, Voderholzer U, Spiegelhalder K, Hornyak M, Buysse DJ, Nissen C, Hennig J, Perlis ML, van Elst LT, Feige B. Chronic insomnia and MRI-measured hippocampal volumes: a pilot study. Sleep. 2007;30:955–958. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.8.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson GE, Grozinger CM, Whitfield CW. Sociogenomics: social life in molecular terms. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:257–270. doi: 10.1038/nrg1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saper CB, Scammell TE, Lu J. Hypothalamic regulation of sleep and circadian rhythms. Nature. 2005;437:1257–1263. doi: 10.1038/nature04284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoofs D, Preuss D, Wolf OT. Psychosocial stress induces working memory impairments in an n-back paradigm. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2008;33:643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seugnet L, Boero J, Gottschalk L, Duntley SP, Shaw PJ. Identification of a biomarker for sleep drive in flies and humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19913–19918. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609463104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seugnet L, Suzuki Y, Vine L, Gottschalk L, Shaw PJ. D1 receptor activation in the mushroom bodies rescues sleep-loss-induced learning impairments in Drosophila . Curr Biol. 2008;18:1110–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shang Y, Griffith LC, Rosbash M. Light-arousal and circadian photoreception circuits intersect at the large PDF cells of the Drosophila brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:19587–19594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809577105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw PJ, Franken P. Perchance to dream: solving the mystery of sleep through genetic analysis. J Neurobiol. 2003;54:179–202. doi: 10.1002/neu.10167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw PJ, Cirelli C, Greenspan RJ, Tononi G. Correlates of sleep and waking in Drosophila melanogaster . Science. 2000;287:1834–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5459.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw PJ, Tononi G, Greenspan RJ, Robinson DF. Stress response genes protect against lethal effects of sleep deprivation in Drosophila . Nature. 2002;417:287–291. doi: 10.1038/417287a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeba V, Fogle KJ, Kaneko M, Rashid S, Chou YT, Sharma VK, Holmes TC. Large ventral lateral neurons modulate arousal and sleep in Drosophila . Curr Biol. 2008;18:1537–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen JG, Nielsen MM, Loeschcke V. Gene expression profile analysis of Drosophila melanogaster selected for resistance to environmental stressors. J Evol Biol. 2007;20:1624–1636. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2007.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tafti M, Maret S, Dauvilliers Y. Genes for normal sleep and sleep disorders. Ann Med. 2005;37:580–589. doi: 10.1080/07853890500372047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai N, Yamaguchi M, Aragaki T, Eto K, Uchihashi K, Nishikawa Y. Effect of psychological stress on the salivary cortisol and amylase levels in healthy young adults. Arch Oral Biol. 2004;49:963–968. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamakoshi A, Ohno Y. Self-reported sleep duration as a predictor of all-cause mortality: results from JACC study, Japan. Sleep. 2004;27:51–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson NF, Goldberg J, Arguelles L, Buchwald D. Genetic and environmental influences on insomnia, daytime sleepiness, and obesity in twins. Sleep. 2006;29:645–649. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.5.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou D, Xue J, Chen J, Morcillo P, Lambert JD, White KP, Haddad GG. Experimental selection for Drosophila survival in extremely low O2 environment. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]