Abstract

Background. Because Mycoplasma genitalium is a prevalent and emerging cause of sexually transmitted infections, understanding the mechanisms by which M. genitalium elicits mucosal inflammation is an essential component to managing lower and upper reproductive tract disease syndromes in women.

Methods. We used a rotating wall vessel bioreactor system to create 3-dimensional (3-D) epithelial cell aggregates to model and assess endocervical infection by M. genitalium.

Results. Attachment of M. genitalium to the host cell's apical surface was observed directly and confirmed using immunoelectron microscopy. Bacterial replication was observed from 0 to 72 hours after inoculation, during which time host cells underwent ultrastructural changes, including reduction of microvilli, and marked increases in secretory vesicle formation. Using genome-wide transcriptional profiling, we identified a host defense and inflammation signature activated by M. genitalium during acute infection (48 hours after inoculation) that included cytokine and chemokine activity and secretion of factors for antimicrobial defense. Multiplex bead-based protein assays confirmed secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, several of which are involved in leukocyte recruitment and hypothesized to enhance susceptibility to human immunodeficiency type 1 infection.

Conclusions. These findings provide insight into key molecules and pathways involved in innate recognition of M. genitalium and the response to acute infection in the human endocervix.

Keywords: Mycoplasma genitalium, Mycoplasma, sexually transmitted infection, cervix, endocervix, epithelial, immune response, transcriptome

Sexually transmitted bacterial infections are among the most commonly reported notifiable diseases in the United States [1]. Mycoplasma genitalium is an emerging cause of male and female urogenital inflammation and has been implicated in male urethritis [2] and in several lower and upper reproductive tract syndromes of women, including cervicitis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and tubal-factor infertility [3, 4]. M. genitalium can persist for extended periods at urogenital sites, including the endocervix [5–8]. However, mechanistic evidence for establishment and persistence of infection remains scarce. Importantly, the host innate and adaptive immune responses are largely unknown and serve as impediments to our understanding of the pathogenesis of M. genitalium infection.

Several lines of clinical evidence exist for M. genitalium as an independent cause of cervical inflammation [3, 4]. First, M. genitalium is a common endocervical infection, with prevalence values on par with those of other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and has been associated significantly with cervicitis in pooled calculations of risk from 14 studies of high- and low-risk populations (odds ratio, 2.2; 95% confidence interval, 1.6–2.9) [4]. In addition, persistent cervical infection appears to be common, with an incidence of chronic M. genitalium infection of >20% in one longitudinal study [6]. Last, although the primary site(s) of infection is unknown, the mechanisms of disease are intriguing because M. genitalium has the smallest genome of any known human bacterial pathogen [9] and, consequently, represents a minimal bacterium to investigate mucosal pathogenesis.

Experimental evidence also supports the hypothesis that M. genitalium infection can lead to mucosal inflammation at female urogenital sites. First, the organism can survive and replicate in cultures of human vaginal, cervical, and endometrial epithelial cells [10–12], resulting in acute and persistent proinflammatory responses [10, 11]. Among lower reproductive tract sites, human endocervical epithelial cells are most responsive to M. genitalium infection [11], during which secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines appears to be mediated in part by activation of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) [13–15]. Intracellular localization is hypothesized to be an important strategy for evasion of the host immune response and has been observed clinically [16]. However, outside of focused evaluations of acute and persistent cytokine responses, the pathologic consequences of endocervical M. genitalium infection and host response are almost entirely unknown.

We used a well-characterized and physiologically relevant model of human endocervical epithelial cells [17] to study interactions of M. genitalium with the host cell. This organotypic model effectively recapitulates physical structural and barrier properties necessary for studying host-microbe interactions [18]. Previously, microbial products have been shown to elicit a specific endocervical innate immune signature that included antimicrobial peptide and mucin expression [19]. Using next-generation sequencing and human transcriptome analysis, we report key cellular pathways that are activated during acute M. genitalium infection. Comparative analyses provide unique insight into the mechanisms of reproductive tract inflammation induced by M. genitalium.

METHODS

Generation of 3-Dimensional (3-D) Endocervical Aggregates and Cellular Response Assays

Human endocervical epithelial cells (A2EN) were isolated from clinically obtained tissues and immortalized as described previously [20]. A2EN cells were cultured in the rotating wall vessel bioreactor with collagen-coated dextran microcarrier beads to form aggregates (Figure 1A) in a single layer with a cobblestone appearance (Figure 1B), as described previously [17]. Differentiated 3-D endocervical aggregates were distributed evenly into 24-well plates for infection and experimental manipulation (6–8 × 105 cells/mL). Secreted cytokines were quantified from culture supernatants, using the Milliplex MAP cytometric bead array assay (human premixed 14-plex panel of cytokine/chemokine targets; Millipore, Billerica, MA). Epithelial cell cytotoxicity was determined using the Cytotoxicity Detection KitPLUS (Roche Applied Science, Indianapolis, IN) in accordance with the manufacturer's suggested protocol, as described previously [10]. Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction quantification of antimicrobial peptide gene expression was performed as described previously [19].

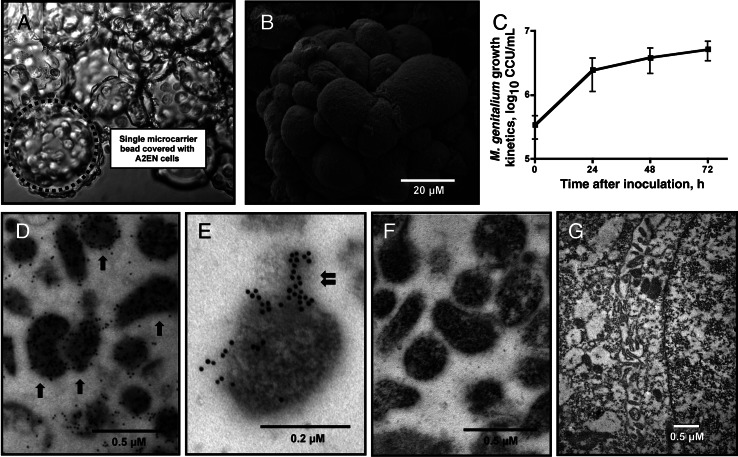

Figure 1.

Mycoplasma genitalium replication and immunoelectron microscopy. A and B, Immortalized human endocervical epithelial cells were cultivated in the rotating wall vessel bioreactor on collagen-coated microcarrier beads, ultimately forming tissue-like epithelial aggregates. The dotted circle indicates a single microcarrier bead (A); most beads were covered completely with A2EN cells, forming differentiated endocervical aggregates. An individual bead covered with a single layer of A2EN cells with a cobblestone-like appearance is pictured (B). C, The growth kinetics of viable M. genitalium organisms was quantified from 0 to 72 hours after inoculation, using a modified color-changing unit (CCU) assay. D–G, Shown are results from an empirically optimized protocol that was based on an immunoelectron microscopy procedure we developed. M. genitalium strain G37 was first grown axenically to mid-log phase in Friis medium and then processed for immunoelectron microscopy (D and E). Arrows indicate individual M. genitalium organisms after immunoelectron microscopy; the double-arrow denotes the M. genitalium tip organelle. To assess nonspecific binding of the secondary antibody, M. genitalium organisms were processed identically but without primary P1B labeling (F). Nonspecific binding of the P1B antibody to host cellular components was assessed by probing mock-inoculated aggregates, followed by secondary gold labeling (G).

M. genitalium Strain Information, Culture Conditions, and Bacterial Titration

The G37 type strain of M. genitalium was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (reference no. 33530) and cultured in modified Friis FB medium [21] at 37°C without CO2. Mid-log phase organisms were harvested, washed 3 times with PBS, and used to inoculate the 3-D endocervical aggregates. Viable M. genitalium organisms were quantified from endocervical aggregate cultures, using a modified 96-well color changing unit assay as described previously [11]. Heat inactivation was accomplished by incubation of high-titer log-phase organisms at 80°C for 5 minutes. The absence of viability following heat treatment was verified by a lack of bacterial growth in Friis medium at 37°C for 14 days.

Electron Microscopy

Human endocervical aggregates were fixed, processed for electron microscopy, and imaged as described previously [17, 22]. For immunoelectron microscopy, fixed specimens were dehydrated by sequential exposure to 40%–80% ethanol (10 minutes each), followed by three 1-minute washes with 100% ethanol. Samples were embedded into gel capsules, using LR White resin (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) and polymerized by use of UV light for 24 hours at 4°C. Next, the sections were blocked and exposed to a 1:250 dilution of P1B polyclonal rabbit antiserum (provided by Dr Jorgen S. Jensen, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark) for 15 minutes at room temperature, followed by overnight incubation at 4°C. The secondary gold-conjugated antibody was diluted 1:50 in 1% bovine serum albumin solution (goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G 10 nm conjugate; MP Biomedical, Solon, OH) and applied to the sections for 1 hour at room temperature. Last, sections were stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate and air-dried for imaging.

RNA Preparation and Sequencing

From 3 independent studies, RNA was isolated from 3-D endocervical aggregates 48 hours after inoculation, using the RNeasy MIDI kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol, with optional DNAse treatment. The efficacy of DNAse treatment was verified by quantitative PCR analysis of GAPDH DNA levels [23], whereby <10 copies were detected per eluted RNA sample. The purity of extracted RNA was verified by UV spectrophotometry on the NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). RNA integrity was assessed using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Foster City, CA). Equal 1-μg quantities of RNA were pooled from each experiment and used for library preparation (truSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit v2), cluster generation (TruSeq Single Read Cluster generation Kit v3-cBot-HS), and messenger RNA sequencing (mRNA-Seq; TruSeq SBS Kit v3-HS) on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA). mRNA-Seq was conducted by SeqWright according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Pathway Analysis and Bioinformatics

Raw sequencing reads were mapped to the annotated human genome hg19 assembly (Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 37), using CLC Genomics Workbench, version 5.5 (CLC bio, Aarhus, Denmark). Fold-change values using normalized fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments mapped (FPKM) were generated for all annotated genes by calculating the sum of the expression values in each sample, dividing the input values by the expression value sum within each sample, and multiplying by the factor 1 × 106. Normalized FPKM values were used for comprehensive pathway analysis by MetaCore, version 6.0 (GeneGo, Carlsbad, CA). Genes that were not expressed in either group (FPKM = 0) and/or genes that were not found in the Consensus CDS database (available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/CCDS) were excluded prior to pathway analysis. A FPKM pseudocount of 0.01 was added to all genes to allow log2-fold calculations between M. genitalium and mock-inoculated groups (log2-fold cutoff, 1.5). Pathways were identified and retained on the basis of functional relationships among the most differentially expressed genes between the groups (false-discovery rate–adjusted P ≤ .05). The most common functional groups among the top 200 GeneGO processes and GeneGO molecular functions were then manually identified. Host defense and inflammation-related pathways were explored in more detail, using a log2-fold cutoff of ±0.85, followed by exclusion of genes with a FPKM value of <0.5 in either the mock-inoculated or M. genitalium–inoculated group. Heat maps were generated in Mac OS X, using R, version 2.15.1.

RESULTS

Ultrastructural Alterations Following Acute M. genitalium Infection of 3-D Endocervical Aggregates

Prior to M. genitalium inoculation, scanning electron microscopy revealed a single layer of epithelial cells on the collagen-coated microcarrier beads (Figure 1A), forming differentiated aggregates (Figure 1B) with a cobblestone-like appearance. This was consistent with the simple endocervical epithelium in vivo. Among 3 independent experiments, we observed >10-fold increases in viable bacterial titers from 0 to 72 hours after infection (Figure 1C), indicating robust replication of the organism in cultures of 3-D endocervical aggregates. To more specifically characterize the interactions of M. genitalium with the host epithelial cell, we first investigated the P1B rabbit antiserum (generated against whole M. genitalium lysates) for its usefulness in immunoelectron microscopy. When we probed axenically grown M. genitalium G37 organisms, the P1B antiserum (generated against whole M. genitalium lysates) showed concentrated immunolabeling of the bacterial cells and few gold particles seen in extracellular spaces (Figure 1D and 1E). Gold particles appeared to be concentrated on the tip organelle for some but not all organisms. No gold particles were observed in sections of axenically grown organisms when the primary antiserum was withheld (Figure 1F) or when mock-inoculated aggregates were probed using P1B followed by secondary gold labeling (Figure 1G).

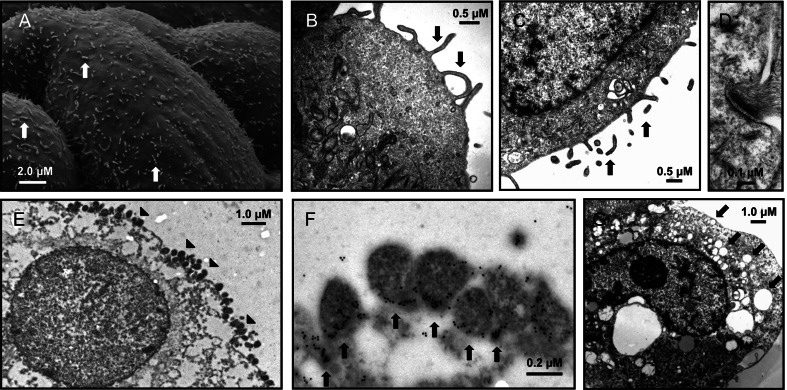

Prior to bacterial inoculation, microvilli were abundant 24 hours (Figure 2A) and 48 hours (Figure 2B and 2C) after harvest from the rotating wall vessel bioreactor. Hemidesmosomes, asymmetrical membrane complexes involved in cell-cell adhesion in epithelial membranes, were observed at cell-cell junctions throughout the endocervical aggregates (Figure 2D). Together, the 3-D endocervical aggregates exhibited several characteristics of the in vivo epithelium, as described previously [19]. Secretory vesicle formation appeared to be minimal in mock-inoculated cells 48 hours after inoculation (Figure 2B and 2C), but marked increases in vesicle formation were observed after M. genitalium inoculation (MOI 20; Figure 2G). Using the optimized immunoelectron microscopy procedure, we observed that when 3-D endocervical aggregates were exposed to M. genitalium (the multiplicity of infection [MOI] was 500, for the purpose of electron microscopy), bacterial attachment to the apical cellular surface was extensive (Figure 2E and 2F), with specific localization of gold particles to the tip organelle or at the junction of cellular attachment (Figure 2F). Evidence of intracellular localization was sparse and observed in <5% of examined cells, a finding also observed at the lower MOI of 20 (data not shown). The P1B antiserum appeared to be highly specific for M. genitalium, whereby very few gold particles were bound to host cell structures in sections of infected 3-D endocervical aggregates.

Figure 2.

Ultrastructural characteristics of acute Mycoplasma genitalium infection of 3-dimensional (3-D) endocervical aggregates. Prior to M. genitalium inoculation, electron microscopy of mature 3-D endocervical aggregates revealed abundant microvilli on the apical cell surface (A–C; arrows) and, together with abundant desmosomes (D), served as markers of cell polarization. Endocervical aggregates were inoculated first with a high inoculum of M. genitalium (multiplicity of infection, 500) to facilitate visualization of bacterium-host cell interactions 48 hours after inoculation (E; attached M. genitalium organisms are marked with arrowheads). Confirmation of pleomorphic M. genitalium organisms at the apical cell surface was accomplished with immunoelectron microscopy, whereby gold particles were concentrated on the tip organelle or at the junction of cell attachment (F; arrows). Increased secretory activity (arrows) and absence of abundant microvilli in response to acute M. genitalium infection were visualized by electron microscopy 48 hours after inoculation (G).

Genome-Wide Host Transcriptional Response to Acute M. genitalium Infection of 3-D Endocervical Aggregates

Using Illumina sequencing and bioinformatics tools, we detected a total of 524 Consensus CDS–annotated genes upregulated (log2-fold ≥1.5) and 803 genes downregulated (log2-fold less than or equal to −1.5) in response to M. genitalium 48 hours after inoculation (Supplementary Materials). MetaCore pathway analysis indicated that 1256 GeneGO processes and 73 GeneGO molecular function pathways were upregulated significantly (false-discovery rate–adjusted P ≤ .05) 48 hours after M. genitalium inoculation. Considering all downregulated genes, 802 GeneGO processes and 75 GeneGO molecular function pathways differed significantly between treatment groups. The most common functional groups of activated cellular pathways identified from GeneGO processes and GeneGO molecular function pathways are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Results of MetaCore Pathway Analysis Showing Functional Grouping of GeneGO Processes Modulated Significantly 48 Hours After M. genitalium Inoculation of Human 3-Dimensional Endocervical Aggregates

| GeneGO Processes |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Groupa | Upregulated, No. | P, Mean | Downregulated, No. | P, Mean |

| Defense and inflammation | 28 | 2.83 × 10–7 | 7 | 4.33 × 10–6 |

| Phospholipase and lipase activity | 20 | 2.70 × 10–11 | 6 | 8.22 × 10–8 |

| cAMP and adenylate cyclase activity | 15 | 1.51 × 10–12 | 13 | 1.68 × 10–7 |

| Ion homeostasis and transporter activity | 7 | 6.97 × 10–8 | 29 | 2.93 × 10–7 |

Abbreviation: cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophosphate.

a The most common functional groups were compiled from the top 200 GeneGO processes identified during MetaCore pathway analysis.

Table 2.

Results of MetaCore Pathway Analysis Showing Functional Grouping of GeneGO Molecular Functions Modulated Significantly 48 Hours After Mycoplasma genitalium Inoculation of Human 3-Dimensional Endocervical Aggregates

| GeneGO Molecular Functions |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Groupa | Upregulated, No. | P, Mean | Downregulated, No. | P, Mean |

| Ion homeostasis and transporter activity | 12 | 9.11 × 10–4 | 29 | 2.46 × 10–4 |

| Defense and inflammation | 8 | 1.22 × 10–4 | 6 | 1.62 × 10–3 |

| Melanocortin and GPCR binding | 5 | 3.30 × 10–22 | 2 | 1.85 × 10–3 |

Abbreviation: GPCR, G-protein coupled receptor.

a The most common functional groups were compiled from all GeneGO molecular functions identified during MetaCore pathway analysis (n = 73).

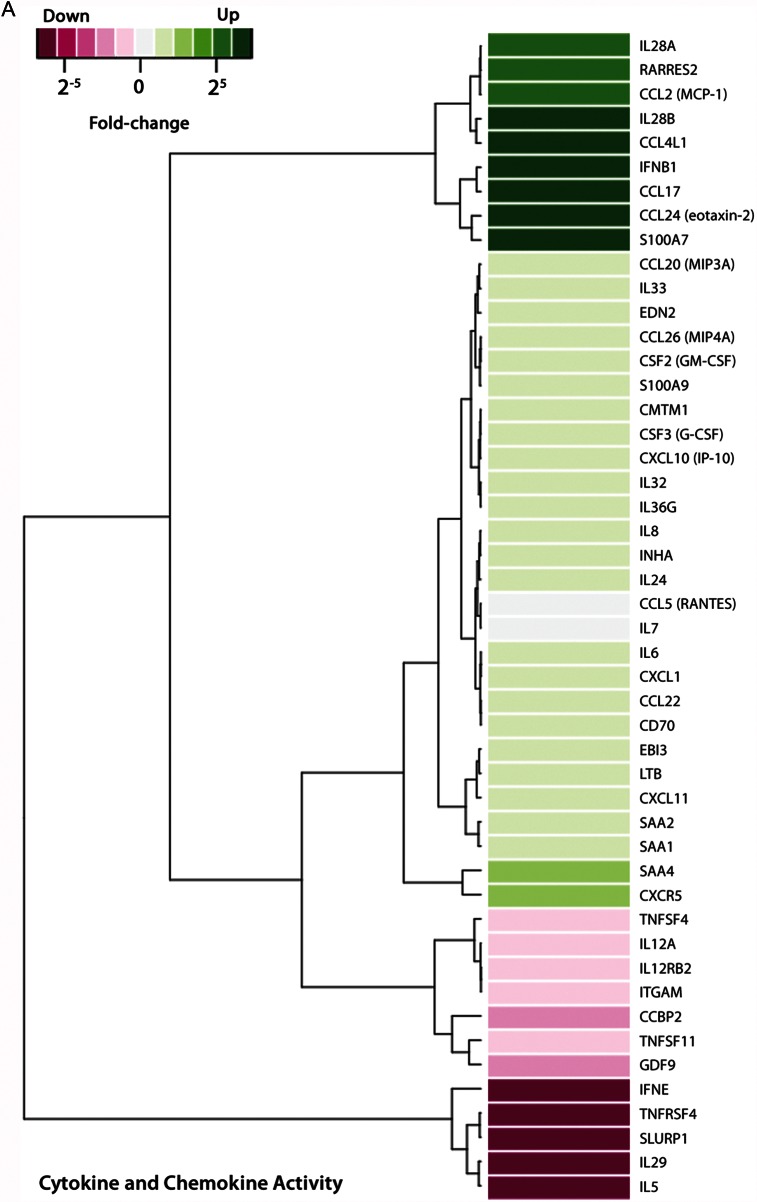

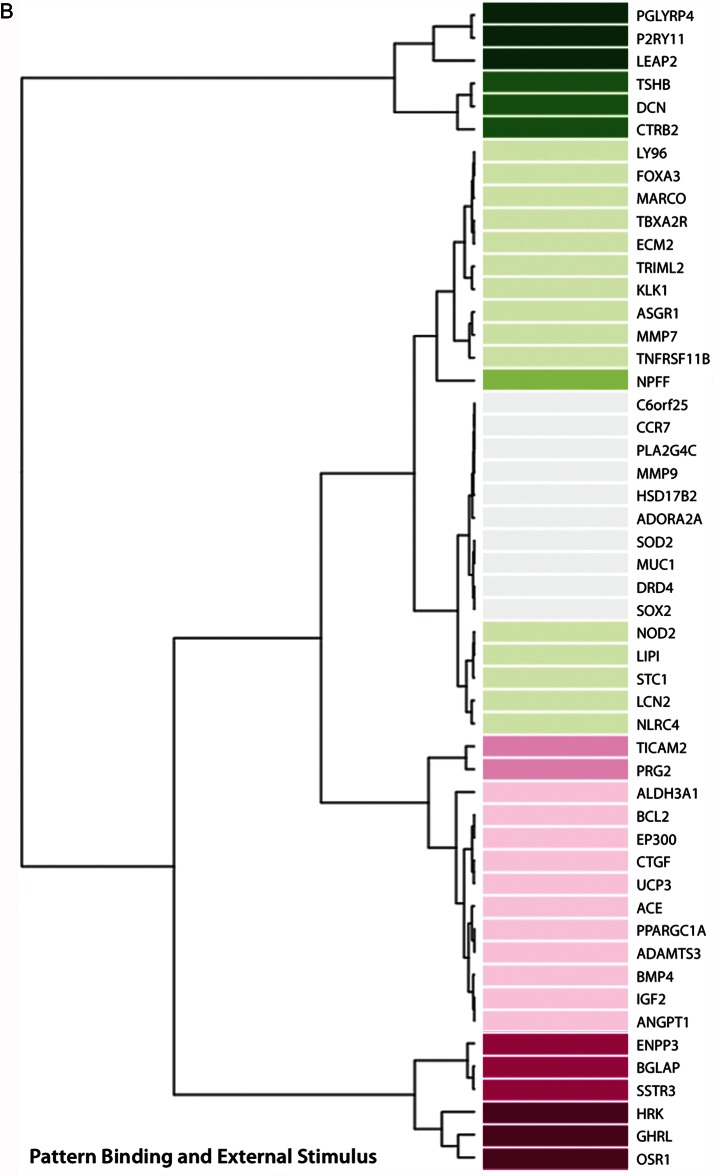

Detailed exploration of host defense and inflammation-related pathways yielded 3 groups of genes upregulated or downregulated in response to M. genitalium infection (Figure 3). Expression of >30 genes increased in response to infection, including those encoding proinflammatory cytokines/chemokines and associated receptors, or molecules involved in cytokine/chemokine signaling pathways (Figure 3A). In addition, 51 genes associated with pathways related to pattern binding and response to external stimuli, antimicrobial peptides, and the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2 (NOD2) receptor were upregulated in M. genitalium–infected 3-D endocervical aggregates (Figure 3B). Genes significantly upregulated or downregulated from the third functional group, consisting of defense and inflammation-related genes, are presented in Figure 3C.

Figure 3.

Human genome-wide transcriptional response to Mycoplasma genitalium infection by 3-dimensional (3-D) endocervical aggregates. Forty-eight hours after inoculation with M. genitalium G37 (multiplicity of infection, 20), host transcriptome analysis of 3-D endocervical aggregates was assessed using next-generation sequencing and bioinformatics tools. MetaCore pathway analysis (log2-fold cutoff, 1.5) revealed that host defense and inflammation-related genes were most commonly activated and comprised 3 functional groups: cytokine and chemokine activity, pattern binding and external stimulus, and other defense and inflammation.

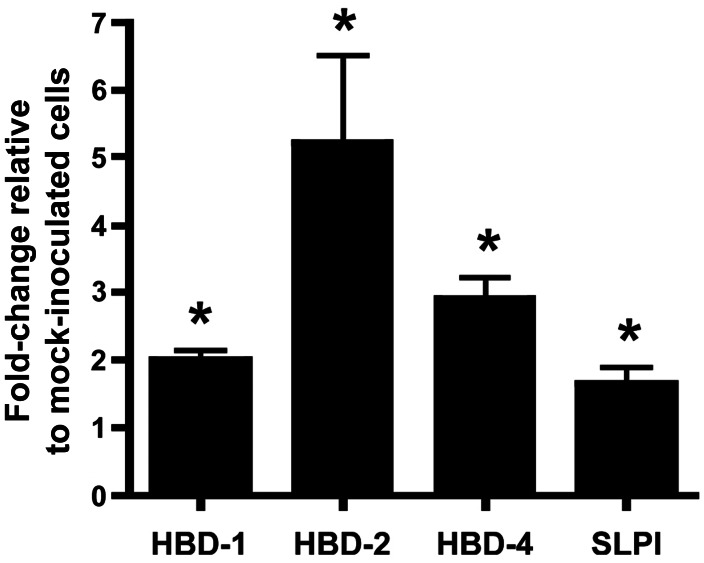

Expression of 3 human β defensin genes (hBD1, hBD2, and hBD4) was significantly increased (P < .05, by the Student t test) in 3-D endocervical aggregates after M. genitalium infection as compared to mock-inoculated aggregates (Figure 4). Expression of the secreted leukocyte peptidase inhibitor gene (SLPI), which encodes an important antimicrobial peptide of the reproductive tract, was also moderately increased in M. genitalium–infected cells (P < .05; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Transcriptional modulation of select antimicrobial peptide genes in 3-dimensional endocervical aggregates. Differences in messenger RNA expression for 3 human β defensins (HBD-1, HBD-2, and HBD-4) and the secreted leukocyte peptidase inhibitor (SLPI) were evaluated by quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction in human endocervical aggregates inoculated 48 hours earlier with Mycoplasma genitalium G37. To account for differences in cell numbers between treatment groups, samples from replicate experiments were normalized to mean GAPDH expression levels. Data are expressed as normalized mean fold-changes relative to mock-inoculated cells (± standard error of the mean). *P < .05, by the Student t test, in normalized copies of each gene as compared to mock-inoculated control cells.

M. genitalium Elicited Proinflammatory Cytokine and Chemokine Secretion, but High Organism Loads Were Required for Cytotoxicity

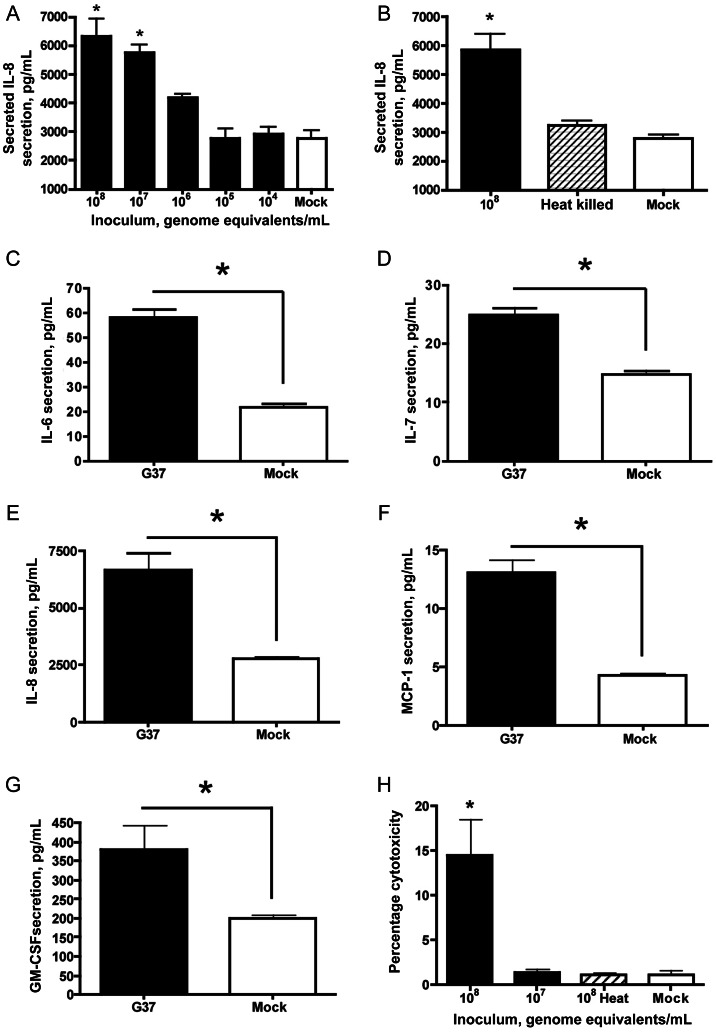

Compared with mock-inoculated endocervical aggregates, significant secretion of interleukin 6 (IL-6), interleukin 7 (IL-7), interleukin 8 (IL-8), monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1), and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) was observed 48 hours after inoculation, at inocula of 1 × 107–1 × 108 genome equivalents/mL (P < .05, by analysis of variance; data for IL-8 are shown in Figure 5A), indicating that the threshold for innate stimulation in this model system was 1 × 106–1 × 107 mycoplasmas/mL (MOIs, 5–50). After heat treatment of the bacterial inoculum, the inflammatory capacity of M. genitalium was almost completely ablated (data for IL-8 are shown in Figure 5B). By using an MOI of 20, significant secretion of IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, MCP-1, and GM-CSF into culture supernatants was observed 24, 48, and 72 hours after inoculation relative to mock-inoculated cells (P < .05, by the Student t test; data at 48 hours are shown in Figure 5C–5G). Cytokines that were tested for but not found to change significantly relative to mock-inoculated cells (P > .05, by the Student t test) included interferon γ, interleukin 1β, interleukin 2, interleukin 4, interleukin 5, interleukin 10, interleukin 12(p70), interleukin 13, and tumor necrosis factor α.

Figure 5.

Cytokine secretion and cellular cytotoxicity elicited by Mycoplasma genitalium infection. Human 3-dimensional endocervical aggregates were inoculated with M. genitalium G37 (multiplicity of infection, 20), and cytokine/chemokine secretion was measured from culture supernatants 48 hours after inoculation. Deescalating doses (A) and heat-killing of M. genitalium (B) organisms were first used to characterize basic innate responses in the novel 3-D model system (interleukin 8 [IL-8] is shown as a representative chemokine). The profile of cytokine and chemokine response is represented by interleukin 6 (IL-6; C), interleukin 7 (IL-7; D), interleukin 8 (IL-8; E), monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1; F), and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF; G). Cytotoxicity engendered by acute M. genitalium infection was evaluated using deescalating doses combined with heat-killing of the inoculum (H). Cytotoxicity data are expressed as percentage cytotoxicity as described in Methods. Data for all panels represent the mean ± standard error of the mean from 3 independent studies (each performed in triplicate wells) normalized to the mean determined from replicate studies. *P < .05, by analysis of variance (A, B, and H) or the Student t test (C–G), for differences in cytokine secretion or cytotoxicity as compared to mock-inoculated control cells.

Cytotoxicity, as measured by cellular lactate dehydrogenase leakage into supernatants of 3-D endocervical aggregate cultures, was significant at the highest inoculum of 1 × 108 mycoplasmas/mL (P < .05, by analysis of variance). Similar to the capacity to elicit cytokine secretion, the cytotoxic effect was ablated after heat killing of the organism (Figure 5H).

DISCUSSION

Models that most accurately recapitulate the in vivo environment are crucial to gathering meaningful experimental data, and ultimately provide enhanced value to managing disease in the clinical setting. The rotating wall vessel bioreactor generates differentiated 3-D epithelial aggregates that are structurally and functionally different from 2-dimensional (monolayer) cell cultures that lack directionality and the architecture characteristic of mucosal tissues in vivo. Apical-basolateral polarity was illustrated in our 3-D endocervical aggregates, with evidence of hemidesmosomes and tight junction formation, as well as prominent microvilli on the apical surface of the cells (Figure 2). Replication of M. genitalium in this system was robust and on par with other models of epithelial infection [10, 11], thereby validating this challenge model of acute infection. The observed interaction of M. genitalium with the apical cell surface highlights the importance of the tip organelle [24] for attachment to human epithelial cells, since virtually all attached organisms showed gold particles concentrated on the tip structure (Figure 2). Localization of anti–M. genitalium antibodies to the tip organelle is explained by the fact that the MgPa protein is not only an important functional component of the tip organelle [25], but also the most potent immunogen in men and women [26–29] and experimentally inoculated laboratory animals [30–35]. Interestingly, despite clearly established interactions of M. genitalium with the epithelial membrane, NOD2 was the only pattern recognition receptor gene activated in response to acute infection. This is somewhat surprising considering the significant lipoprotein composition of mycoplasmas and the previous reports of M. genitalium's ability to bind TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6 [13–15]. However, TLR2 and TLR6 are highly expressed in these endocervical epithelial cells in the absence of infection [20], suggesting that increased transcription may not be necessary for their functional response to acute infection. The ability of MD-2 to enhance TLR2-mediated recognition of bacteria [36] might be an important component of the response to M. genitalium infection, since we observed a >4-fold increase in expression in our studies.

Of significant interest is the approximately 200-fold induction of secreted peptidoglycan recognition receptor 4 (PGLYRP4) expression during M. genitalium infection. All mycoplasma species lack a peptidoglycan-containing cell wall, and therefore it is hypothesized that increased PGLYRP4 expression is part of the innate host defense initiated by TLR2 and NOD2 binding. However, whether PGLYRP4 has a role in controlling M. genitalium infection or a secondary effect on other reproductive tract microbes is unclear. Expression of SLPI, which encodes a peptide that is essential to antimicrobial activity in the reproductive mucosae and a common component of cervical mucus [37, 38], was moderately increased following M. genitalium inoculation. Microbial products such as polyinosinic:cytidylic acid and outer membrane components such as diacylated and triacylated lipoproteins have been shown to induce expression of antimicrobial peptides, including SLPI, in 3-D endocervical aggregates [19]. Additionally, it has been shown that HBD proteins are produced in 3-D endocervical aggregates and that HBD1 and HBD2 expression is induced following exposure to TLR agonists [19]. The observed pattern of hBD1, hBD2, and hBD4 upregulation appears to be unique to M. genitalium, since it has not been previously observed following exposure of 3-D endocervical aggregates to other bacterial and viral components. In addition, increased expression of genes encoding the macrophage receptor with collagenous structure and the liver-expressed antimicrobial peptide 2 is, to our knowledge, novel and not a previously described component of the mucosal response to mycoplasmas. Together, although a clear-cut mechanism for innate activation by M. genitalium remains absent, antibacterial factors, including antimicrobial peptides, are likely components of the host response and induced through specific extracellular pattern recognition receptor activation.

Intracellular survival of M. genitalium could provide a protected niche for bacterial persistence, since intracellular organisms have been observed in cultured epithelial cells of the vagina, endocervix and ectocervix, and endometrium [11, 12, 39–41]. In contrast to 2-D cultures of the same A2EN cells [11], very few intracellular mycoplasmas were observed in the 3-D organotypic endocervical aggregates. This could be attributed to functional barrier properties (eg, mucins and select antimicrobial peptides) that are present in 3-D but not 2-D epithelial cultures [19, 22] and likely impact adherence and invasion of M. genitalium. In endocervical aggregates, MUC1 expression was upregulated 1.9-fold in response to M. genitalium, but considering that 16 other related mucins were not upregulated, induction of mucin expression does not seem to be a significant component of the acute-phase response. Importantly, mucin expression has been readily observed in uninfected 3-D endocervical aggregates and has been induced following exposure to specific microbial products [19]. These findings further highlight that unique innate immune responses are generated by endocervical epithelia and can be linked to specific pathogens or microbial products.

Together with previous observations [10, 11], an acute immunologic response signature by endocervical epithelial cells infected with M. genitalium has been identified and includes secretion of IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, GM-CSF, and MCP-1. This proinflammatory component of the signature includes cytokines and chemokines involved in recruitment of leukocytes and/or activation and differentiation of monocytes and macrophages. In the current work, genome-wide transcriptional profiling indicated that host defense and inflammation-related pathways were most commonly activated during acute infection (Figure 3). Of these, 11 chemokines or molecules involved in leukocyte recruitment were upregulated in response to M. genitalium infection, with 8 known to be chemotactic for T lymphocytes and 5 known to attract peripheral monocytes. Collectively, the finding that M. genitalium activates inflammation and host defense pathways not only paralleled results from previous protein-based studies [10, 11, 14], but specific analysis of genes within these pathways also served to highlight novel aspects of the immune response to this organism and support the role of M. genitalium in female reproductive tract disease.

One such novel response observed in these studies of 3-D endocervical aggregates was the significant secretion of IL-7 after M. genitalium infection. IL-7 has been shown to enhance human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) entry into thymocytes through CXCR4 [42] and to stimulate HIV replication in vitro [43, 44]. Virtually all peripheral T lymphocytes express the IL-7 receptor [45], and therefore IL-7 signaling in the context of STIs is of great interest because CD4+ T lymphocytes and macrophages are most commonly targeted by HIV type 1. Recruitment of susceptible cells to the lower reproductive tract mucosa is a plausible mechanism for the enhanced susceptibility of M. genitalium–infected subjects to HIV infection [46]. Interestingly, IL-7 also is detected more often in vaginal secretions from women with other STIs, relative to subjects without infection [47]. The prominent clinical link between M. genitalium and HIV infection status [48], combined with the strong association with cervicitis, provide a compelling rationale for further investigation of HIV–M. genitalium coinfection.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that key cellular responses are elicited by M. genitalium in human endocervical epithelial cells; we define these responses as an innate immune signature characteristic of acute infection. The 3-D endocervical model provides an excellent tool for investigation of mucosal pathogenesis, and results from our study provide a strong rationale for evaluating endocervical responses to M. genitalium infection in the clinical research setting. Continued examination of M. genitalium as a STI is imperative to our overall understanding of reproductive tract disease syndromes of women.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at The Journal of Infectious Diseases online (http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/). Supplementary materials consist of data provided by the author that are published to benefit the reader. The posted materials are not copyedited. The contents of all supplementary data are the sole responsibility of the authors. Questions or messages regarding errors should be addressed to the author.

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Dave Lowry, from the Arizona State University (ASU; Phoenix) Life Sciences Electron Microscopy Laboratory, for technical assistance; Dr Jorgen Skov Jensen, from the Statens Serum Institut, for providing the polyclonal antiserum; and Brooke Hjelm, from ASU, and the Translational Genomics Research Institute (Phoenix), for scientific guidance of pathway analysis and interpretation.

Financial support. This work was supported by the US Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity (grant W81XWH-08–1–0676); the Sexually Transmitted Infection/Topical Microbicide Cooperative Research Center, National Institutes of Health (grants U19 AI061972 and U19 AI062150–01); and the Alternatives Research Development Foundation (to M. M. H.-K).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Sexually transmitted infections. August 2011. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs110/en/ Accessed 25 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: the aetiological agent of urethritis and other sexually transmitted diseases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:1–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.00923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGowin CL, Anderson-Smits C. Mycoplasma genitalium: an emerging cause of sexually transmitted disease in women. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001324. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor-Robinson D, Jensen JS. Mycoplasma genitalium: from chrysalis to multicolored butterfly. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:498–514. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00006-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradshaw CS, Chen MY, Fairley CK. Persistence of Mycoplasma genitalium following azithromycin therapy. PLoS One. 2008;3:e3618. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen CR, Nosek M, Meier A, et al. Mycoplasma genitalium infection and persistence in a cohort of female sex workers in Nairobi, Kenya. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:274–9. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000237860.61298.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hjorth SV, Bjornelius E, Lidbrink P, et al. Sequence-based typing of Mycoplasma genitalium reveals sexual transmission. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2078–83. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00003-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iverson-Cabral SL, Astete SG, Cohen CR, Rocha EP, Totten PA. Intrastrain heterogeneity of the mgpB gene in Mycoplasma genitalium is extensive in vitro and in vivo and suggests that variation is generated via recombination with repetitive chromosomal sequences. Infect Immun. 2006;74:3715–26. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00239-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraser CM, Gocayne JD, White O, et al. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science. 1995;270:397–403. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGowin CL, Annan RS, Quayle AJ, et al. Persistent Mycoplasma genitalium infection of human endocervical epithelial cells elicits chronic inflammatory cytokine secretion. Infect Immun. 2012;80:3842–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00819-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGowin CL, Popov VL, Pyles RB. Intracellular Mycoplasma genitalium infection of human vaginal and cervical epithelial cells elicits distinct patterns of inflammatory cytokine secretion and provides a possible survival niche against macrophage-mediated killing. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:139. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ueno PM, Timenetsky J, Centonze VE, et al. Interaction of Mycoplasma genitalium with host cells: evidence for nuclear localization. Microbiology. 2008;154:3033–41. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/020735-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He J, You X, Zeng Y, Yu M, Zuo L, Wu Y. Mycoplasma genitalium-derived lipid-associated membrane proteins activate NF-kappaB through toll-like receptors 1, 2, and 6 and CD14 in a MyD88-dependent pathway. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:1750–7. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00281-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGowin CL, Ma L, Martin DH, Pyles RB. Mycoplasma genitalium-encoded MG309 activates NF-kappaB via Toll-like receptors 2 and 6 to elicit proinflammatory cytokine secretion from human genital epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2009;77:1175–81. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00845-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimizu T, Kida Y, Kuwano K. A triacylated lipoprotein from Mycoplasma genitalium activates NF-{kappa}B through TLR1 and TLR2. Infect Immun. 2008;76:3672–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00257-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blaylock MW, Musatovova O, Baseman JG, Baseman JB. Determination of infectious load of Mycoplasma genitalium in clinical samples of human vaginal cells. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:746–52. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.746-752.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radtke AL, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Culturing and applications of rotating wall vessel bioreactor derived 3D epithelial cell models. J Vis Exp. 2012:e3868. doi: 10.3791/3868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barrila J, Radtke AL, Crabbe A, et al. Organotypic 3D cell culture models: using the rotating wall vessel to study host-pathogen interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:791–801. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radtke AL, Quayle AJ, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Microbial products alter the expression of membrane-associated mucin and antimicrobial peptides in a three-dimensional human endocervical epithelial cell model. Biol Reprod. 2012;87:132. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.103366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herbst-Kralovetz MM, Quayle AJ, Ficarra M, et al. Quantification and comparison of toll-like receptor expression and responsiveness in primary and immortalized human female lower genital tract epithelia. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;59:212–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jensen JS, Hansen HT, Lind K. Isolation of Mycoplasma genitalium strains from the male urethra. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:286–91. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.2.286-291.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hjelm BE, Berta AN, Nickerson CA, Arntzen CJ, Herbst-Kralovetz MM. Development and characterization of a three-dimensional organotypic human vaginal epithelial cell model. Biol Reprod. 2010;82:617–27. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.080408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bourne N, Pyles RB, Yi M, Veselenak RL, Davis MM, Lemon SM. Screening for hepatitis C virus antiviral activity with a cell-based secreted alkaline phosphatase reporter replicon system. Antiviral Res. 2005;67:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pich OQ, Burgos R, Querol E, Pinol J. P110 and P140 cytadherence-related proteins are negative effectors of terminal organelle duplication in Mycoplasma genitalium. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burgos R, Pich OQ, Ferrer-Navarro M, Baseman JB, Querol E, Pinol J. Mycoplasma genitalium P140 and P110 cytadhesins are reciprocally stabilized and required for cell adhesion and terminal-organelle development. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:8627–37. doi: 10.1128/JB.00978-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baseman JB, Cagle M, Korte JE, et al. Diagnostic assessment of Mycoplasma genitalium in culture-positive women. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:203–11. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.1.203-211.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clausen HF, Fedder J, Drasbek M, et al. Serological investigation of Mycoplasma genitalium in infertile women. Hum Reprod. 2001;16:1866–74. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.9.1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Svenstrup HF, Fedder J, Kristoffersen SE, Trolle B, Birkelund S, Christiansen G. Mycoplasma genitalium, Chlamydia trachomatis, and tubal factor infertility—a prospective study. Fertil Steril. 2008;90:513–20. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.12.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Svenstrup HF, Jensen JS, Gevaert K, Birkelund S, Christiansen G. Identification and characterization of immunogenic proteins of Mycoplasma genitalium. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2006;13:913–22. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00048-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Furr PM, Taylor-Robinson D. Microimmunofluorescence technique for detection of antibody to Mycoplasma genitalium. J Clin Pathol. 1984;37:1072–4. doi: 10.1136/jcp.37.9.1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moller BR, Taylor-Robinson D, Furr PM, Freundt EA. Acute upper genital-tract disease in female monkeys provoked experimentally by Mycoplasma genitalium. Br J Exp Pathol. 1985;66:417–26. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor-Robinson D, Furr PM, Tully JG, Barile MF, Moller BR. Animal models of Mycoplasma genitalium urogenital infection. Isr J Med Sci. 1987;23:561–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor-Robinson D, Tully JG, Barile MF. Urethral infection in male chimpanzees produced experimentally by Mycoplasma genitalium. Br J Exp Pathol. 1985;66:95–101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tully JG, Taylor-Robinson D, Rose DL, Furr PM, Graham CE, Barile MF. Urogenital challenge of primate species with Mycoplasma genitalium and characteristics of infection induced in chimpanzees. J Infect Dis. 1986;153:1046–54. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.6.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McGowin CL, Spagnuolo RA, Pyles RB. Mycoplasma genitalium rapidly disseminates to the upper reproductive tracts and knees of female mice following vaginal inoculation. Infect Immun. 2010;78:726–36. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00840-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dziarski R, Wang Q, Miyake K, Kirschning CJ, Gupta D. MD-2 enables Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2)-mediated responses to lipopolysaccharide and enhances TLR2-mediated responses to Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and their cell wall components. J Immunol. 2001;166:1938–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumar R, Vicari M, Gori I, et al. Compartmentalized secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor expression and hormone responses along the reproductive tract of postmenopausal women. J Reprod Immunol. 2011;92:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2011.06.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moriyama A, Shimoya K, Ogata I, et al. Secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor (SLPI) concentrations in cervical mucus of women with normal menstrual cycle. Mol Hum Reprod. 1999;5:656–61. doi: 10.1093/molehr/5.7.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baseman JB, Lange M, Criscimagna NL, Giron JA, Thomas CA. Interplay between mycoplasmas and host target cells. Microb Pathog. 1995;19:105–16. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1995.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dallo SF, Baseman JB. Intracellular DNA replication and long-term survival of pathogenic mycoplasmas. Microb Pathog. 2000;29:301–9. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2000.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jensen JS, Blom J, Lind K. Intracellular location of Mycoplasma genitalium in cultured Vero cells as demonstrated by electron microscopy. Int J Exp Pathol. 1994;75:91–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pedroza-Martins L, Gurney KB, Torbett BE, Uittenbogaart CH. Differential tropism and replication kinetics of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates in thymocytes: coreceptor expression allows viral entry, but productive infection of distinct subsets is determined at the postentry level. J Virol. 1998;72:9441–52. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9441-9452.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guillemard E, Nugeyre MT, Chene L, et al. Interleukin-7 and infection itself by human immunodeficiency virus 1 favor virus persistence in mature CD4(+)CD8(-)CD3(+) thymocytes through sustained induction of Bcl-2. Blood. 2001;98:2166–74. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.7.2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pedroza-Martins L, Boscardin WJ, Anisman-Posner DJ, Schols D, Bryson YJ, Uittenbogaart CH. Impact of cytokines on replication in the thymus of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates from infants. J Virol. 2002;76:6929–43. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.14.6929-6943.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mackall CL, Fry TJ, Gress RE. Harnessing the biology of IL-7 for therapeutic application. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:330–42. doi: 10.1038/nri2970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mavedzenge SN, Van Der Pol B, Weiss HA, et al. The association between Mycoplasma genitalium and HIV-1 acquisition in African women. AIDS. 2012;26:617–24. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32834ff690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spear GT, Kendrick SR, Chen HY, et al. Multiplex immunoassay of lower genital tract mucosal fluid from women attending an urban STD clinic shows broadly increased IL1ss and lactoferrin. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19560. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Napierala Mavedzenge S, Weiss HA. Association of Mycoplasma genitalium and HIV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2009;23:611–20. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328323da3e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.