Abstract

Intermittent parathyroid hormone (PTH) administration increases systemic and craniofacial bone mass. However, the effect of PTH therapy on healing of tooth extraction sites is unknown. The aims of this study were to determine the effect of PTH therapy on tooth extraction socket healing and to examine whether PTH intra-oral injection promotes healing. The mandibular first molars were extracted in rats, and subcutaneous PTH was administered intermittently for 7, 14, and 28 days. In a second study, maxillary second molars were extracted, and PTH was administered by either subcutaneous or intra-oral injection to determine the efficacy of intra-oral PTH administration. Healing was assessed by micro-computed tomography and histomorphometric analyses. PTH therapy accelerated the entire healing process and promoted both hard- and soft-tissue healing by increasing bone fill and connective tissue maturation. PTH therapy by intra-oral injection was as effective as subcutaneous injection in promoting tooth extraction socket healing. The findings suggest that PTH therapy promotes tooth extraction socket healing and that intra-oral injections can be used to administer PTH.

Keywords: alveolar bone loss, osteogenesis, inflammation, wounds and injuries, bone remodeling, connective tissue

Introduction

Tooth extraction is a common dental procedure. Although healing is generally uneventful, clinical concerns are the development of alveolar osteitis and delayed/impaired healing in patients with systemic complications such as diabetes and immune diseases and in patients with bone metabolic diseases taking anti-resorptives (Jaafar and Nor, 2000; O’Ryan and Lo, 2012). Therefore, the promotion of healing is important for the prevention/treatment of such complications. Also, extraction socket healing typically results in dimensional loss of the alveolar ridge (Araujo and Lindhe, 2009). Such dimensional loss has a negative impact on subsequent implant therapy. Hence, the preservation of the alveolar ridge during healing is of major interest in implant dentistry.

The intermittent administration of parathyroid hormone (PTH) initially stimulates bone formation and then promotes bone remodeling, with bone formation favored over resorption, resulting in a net increase in bone mass (Dobnig and Turner, 1995). Intermittent PTH therapy has been approved for the clinical treatment of osteoporosis. Despite the well-established anabolic effect of PTH in long bones and vertebrae, the effect of PTH in the alveolar bone has been unclear, and its effect on tooth extraction socket healing is not yet defined (Chan and McCauley, 2013). Since tooth extraction wounds are exposed to an oral environment where multiple oral pathogens reside, not only bone repair but also host-bacteria immune responses play roles in healing. Accordingly, the PTH effect on extraction wound healing could be distinct. Recent pre-clinical and clinical studies indicate that PTH increases bone density of the jaw and promotes the outcome of periodontal surgeries (Bashutski et al., 2010; Bellido et al., 2010), suggesting that PTH can be used to enhance tooth extraction socket healing.

In this study, we hypothesized that PTH therapy promotes tooth extraction socket healing by increasing bone fill, thereby preserving the alveolar ridge. The objectives were: (1) to determine whether PTH enhances bone fill in tooth extraction sockets during healing, and (2) to investigate whether intra-oral PTH injection is effective in promoting tooth extraction socket healing.

Materials & Methods

Two animal studies were performed to achieve the project goals. In Study 1, the mandibular first molars (M1) were extracted, and the effect of systemic PTH therapy on wound healing was assessed. In Study 2, the maxillary second molars (M2) were extracted, and wound healing was compared between rats receiving subcutaneous and those receiving intra-oral injections of PTH.

Animals, Tooth Extractions, and PTH

Eighty Sprague-Dawley rats (6 wks old) were obtained and randomly divided into 10 groups (n = 8/group) (details in the Appendix). Young adult rats were chosen because atraumatic molar extractions are challenges in skeletally mature rats due to the excessive cementum apposition on the apical portion of the roots (Pietrokovski and Massler, 1967). The mandibular left M1s were extracted in 48 rats (6 groups) under anesthesia (ketamine and xylazine cocktail), and PTH (Bachem, Torrance, CA, USA) was administered daily at 80 μg/kg subcutaneously for 7, 14, and 28 days. Saline was used as vehicle control (VC). The dorsal skin was used for subcutaneous injections. The maxillary right M2s were extracted in 32 rats (4 groups), and daily PTH (80 μg/kg) or saline was administered for 10 days. The method of administration was either intra-oral injection or subcutaneous injection in the dorsal skin. For intra-oral injections, the needle was placed in the buccal vestibule next to the tooth extraction site. The experimental protocol was approved by the University Committee on Use and Care of Animals. The manuscript was prepared according to ARRIVE guidelines.

Microcomputed Tomography (microCT) Assessment

Rats were euthanized at the end of the designated injection period. The mandibles and maxillae were dissected and fixed, and the extraction wounds were scanned by microCT (eXplore Locus, GE Healthcare, London, ON, Canada; Scanco µCT-100, Medical AG, Bruttisellen, Switzerland) at 10- to 18-µm voxel resolution with an energy level of 70-80 kV (Kuroshima et al., 2012). The extraction sockets were segmented by semi-manual contouring and analyzed with built-in software. Trabecular parameters were identified by the direct-measures technique (Hildebrand and Ruegsegger, 1997). The dimensional change of the alveolar ridge was evaluated in the mandibles by assessment of the ridge height relative to the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) and the thickness of the bony plates. The interradicular bone of the maxillary M1s was also scanned and analyzed.

Histology

The specimens were demineralized in 10% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, paraffin-embedded, and sectioned. Masson’s trichrome and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) stainings were performed for the detection of collagen fibers and osteoclasts, respectively, following the manufacturer’s instructions (HT15 and 386A; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Immunohistochemical staining for CD68 (Appendix) and hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining were performed with a standard staining protocol. Stained sections were analyzed by Image-Pro (Media Cyberrnetics, Bethesda, MD, USA). Osteoclast and osteoblast surfaces were measured. Empty osteocyte lacunae were quantified within 100 µm of the bone surface. Collagen and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMN) were quantified in the extraction wounds as described previously (Yamashita et al., 2010). The epithelial thickness was measured.

Serum Chemistry

Blood was collected approximately 18 hrs after the last injection of VC or PTH at the time of euthanasia. The levels of serum calcium, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase 5b (TRAcP5b), and amino-terminal propeptide of type I procollagen (P1NP) were measured by C7503 (Pointe Scientific, Canton, MI, USA), Mouse TRAP (IDS, Boldon, UK), and Mouse P1NP (IDS), respectively.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed with Student’s t test. All statistical analyses were conducted with SYSTAT (Systat Software, Chicago, IL, USA). An α-level of 0.05 was used for statistical significance. Results are presented as mean ± SEM.

Results

Subcutaneous PTH Injection Increased Bone Fill

Bone fill in the sockets increased as healing time increased in both PTH and VC groups. However, significantly more bone fill was observed in the PTH group compared with VC at all time-points (Figs. 1A, 1B). The average bone fill at day 14 in the PTH group was similar to that at day 28 in the VC group. The numbers of trabeculae (Tb.N) at day 7 were significantly greater in the PTH than in the VC group, but were significantly fewer at day 28 in the PTH than in the VC group, suggesting dynamic osseous healing in the PTH group. The distance between trabecular bones (Tb.Sp) was closer in the PTH than in the VC group at all time-points. These results suggest that PTH accelerated bone fill and its maturation. The alveolar ridge was better preserved in the PTH than in the VC group (Figs. 1C-1E). Significantly thicker bony plates (r) and less vertical bone loss (h) were noted in the PTH than in the VC group, indicating that PTH suppressed the dimensional loss of the alveolar ridge.

Figure 1.

PTH therapy increased bone fill and preserved the alveolar ridge. (A) Representative sagittal views of the three-dimensional reconstructions of the mandibles. Arrows indicate the extraction sockets of the mandibular first molars. (B) MicroCT assessment of the tooth extraction sockets. PTH therapy significantly increased bone fill and bone mineral density (BMD) at all time-points compared with the VC group. Trabecular numbers (Tb.N) were significantly higher at day 7 but decreased considerably at day 28 in the PTH compared with the VC group. The numbers of trabeculae in the VC group were relatively constant through day 28. Significantly thicker trabecular bone (Tb.Th) and smaller trabecular separation (Tb.Sp) were noted in the PTH than in the VC group at all time-points. (C) The width (r) of the buccal and lingual bony plates was measured and averaged. The distance (h) between the CEJ line and the bony crest was measured on the buccal side. (D) The average width was significantly thicker in the PTH than in the VC group at days 14 and 28. (E) The vertical bone loss increased in the VC group as healing time increased, while, in the PTH group, vertical bone loss did not change until day 14. PTH therapy suppressed the vertical bone loss significantly at days 14 and 28. n = 8 per group, *p < .05, **p < .01.

PTH Therapy Promoted Soft-tissue Maturation

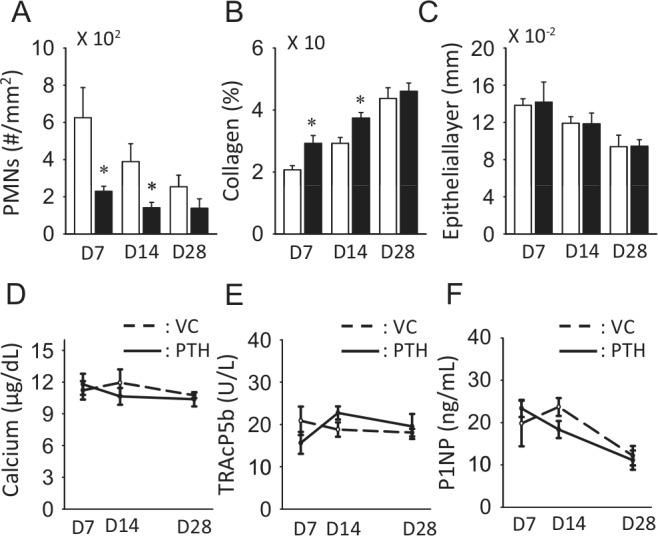

Since tooth extractions cause mechanical injuries with microbial contamination, inflammatory responses occur. As expected, severe PMN infiltration was observed in the VC group at day 7 as compared with day 28 (Fig. 2A). PMN infiltration in the PTH group was significantly low even at day 7. The degree of PMN infiltration at day 7 in the PTH group was as low as that at day 28 in the VC group. The connective tissue maturation was greater in the PTH compared with the VC group at days 7 and 14 (Fig. 2B). No PTH effect was noted in the thickness of the epithelium (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

PTH therapy promoted soft-tissue healing. PTH therapy significantly suppressed PMN infiltration (A) and increased the amount of collagen fibers at days 7 and 14 (B). No differences were noted in the thickness of the epithelium (C). PTH therapy did not alter serum calcium levels (D). No statistically significant differences were noted between the PTH and VC groups at any time-point for the TRAcP5b (E) and P1NP (F) levels. n > 6 per group, *p < .05.

Serum calcium levels did not change with PTH therapy (Fig. 2D). No statistically meaningful changes were observed in serum TRAcP5b and P1NP levels (Figs. 2E, 2F). Since these serum markers reflect whole-body changes, local bone resorption/formation events could be masked.

Intra-oral PTH Injections Promoted Hard-tissue Healing

To explore the efficacy of intra-oral PTH injections, we compared the PTH effects on extraction socket healing using subcutaneous and intra-oral injections. PTH significantly increased bone fill and bone mineral density (BMD) compared with those in the VC group, regardless of the administration route (Fig. 3A). No differences were noted in bone fill and BMD between the subcutaneous and intra-oral injections. However, the parameters of newly formed trabecular bone were different between them. The subcutaneous PTH injections increased trabecular thickness, while the intra-oral injections increased trabecular number at day 10. Decreased trabecular separation was noted in the intra-oral injections but not in the subcutaneous injections. Thus, regardless of the administration route, PTH strongly enhanced hard-tissue healing in the sockets. However, PTH did not exert any effect on interradicular bone (Fig. 3B). No differences were found in bone volume fraction (BVF) and BMD between the VC and PTH groups in the interradicular bone of both the subcutaneous and intra-oral injection groups.

Figure 3.

Subcutaneous vs. intra-oral injections, microCT assessment. (A) The effect of PTH therapy for 10 days on hard-tissue healing within the extraction socket was assessed by microCT, and the results were compared between the subcutaneous (sc) and intra-oral injection groups. PTH therapy significantly increased bone fill and BMD regardless of the injection method. Trabecular bone parameters were different between the subcutaneous and intra-oral injection groups. PTH therapy by intra-oral injections increased trabecular numbers (Tb.N) and decreased trabecular separation (Tb.Sp), while PTH therapy by subcutaneous injection increased the thickness of trabecular bone (Tb.Th). (B) The neighboring interradicular bone of the maxillary first molars was assessed for PTH bone anabolic effects by microCT. Regardless of the method of injections, PTH therapy for 10 days induced no detectable bone anabolic effect in interradicular bone parameters. n = 8 per group, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Intra-oral PTH Injections Enhanced Soft-tissue Healing

PTH therapy for 10 days significantly increased bone formation in the extraction sockets regardless of the administration route (Figs. 4A, 4B). Consistently, osteoblast surfaces (OB.S/BS) were significantly increased by PTH in both the subcutaneous and intra-oral injection groups (Fig. 4C). However, osteoclast surfaces (OC.S/BS) showed different responses to PTH therapy, depending on the administration method (Fig. 4D). Subcutaneous PTH injection significantly decreased osteoclast surfaces in the wounds. Conversely, intra-oral PTH injections considerably increased them. PMN infiltration was significantly suppressed in the PTH compared with the VC group when PTH was injected subcutaneously (Figs. 4E, 4I). When intra-oral VC injection was performed, however, PMN numbers were not as high as those observed with subcutaneous VC injection (Figs. 4E, 4J). However, PMN numbers were low when intra-oral PTH injection was performed. Macrophage numbers were not different when PTH was injected subcutaneously; however, PTH significantly suppressed macrophage numbers compared with those in the VC group when intra-oral injection was used (Fig. 4F). PTH, regardless of the administration routes, significantly increased collagen content in connective tissue (Figs. 4G, 4I, 4J). No differences were noted in the epithelial thickness between the subcutaneous and intra-oral injections of PTH (Fig. 4H).

Figure 4.

Subcutaneous vs. intra-oral injections, histomorphometric assessment. Representative images of the trichrome-stained sections of the extraction sockets of the maxillary second molars in rats receiving the subcutaneous injections (A) and intra-oral injections (B) (Appendix Figs. 1, 2). The results of histomorphometric analysis of the sockets are shown under the images. The yellow dotted lines indicate the outline of the original tooth extraction sockets. Bar = 1 mm. (C) PTH therapy for 10 days significantly increased osteoblast surfaces (OB.S/BS) regardless of the method of PTH administration. (D) Osteoclast surfaces (OC.S/BS) were reduced in the subcutaneous PTH injection animals but increased in those receiving intra-oral PTH injections (Appendix Fig. 3). (E) Both subcutaneous and intra-oral injections of PTH suppressed PMN infiltration, with a significant difference detected only when PTH was administered subcutaneously. (F) Macrophages were visualized with CD68 staining and assessed. No differences were noted between the PTH and VC groups when subcutaneous injections were performed. The intra-oral PTH injection significantly suppressed macrophage numbers compared with the intra-oral VC injection. (G) PTH therapy significantly increased the number of collagen fibers, regardless of the method of administration. (H) No difference was noted in the thickness of the epithelium between the PTH and VC groups, regardless of the administration method. (I, J) Representative photomicrographs of the stained sections of the extraction wounds (upper, HE staining; lower, trichrome staining). Blue-stained fibers in the connective tissue indicate collagen (Appendix Figs. 4, 5). Bar = 250 μm; n > 6 per group, *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that PTH promoted tooth extraction socket healing in rats with increased bone fill, enhanced soft-tissue maturation, and suppressed dimensional loss of the alveolar ridge. The levels of bone fill, BMD, and trabecular bone parameters at day 14 in the PTH group were comparable with those at day 28 in the VC group. This suggests that PTH accelerated hard-tissue healing by 50%. When the PTH effect was compared between the dorsal subcutaneous and intra-oral injections, both administration methods significantly increased bone fill and BMD. Thus, the intra-oral injection could be an effective alternative method for the administration of PTH. In this study, the PTH effect was assessed in the interradicular bone as well. We assessed interradicular bone of the maxillary M1s to obtain the baseline PTH effect in the alveolar bone. Different from the extraction sockets, PTH showed no effect in the interradicular bone at day 10. This finding indicates that PTH actions were more pronounced in wounded vs. intact bone. In other animal studies, evidence is accumulating that PTH increases callus formation, BMD, and strength (Nakajima et al., 2002; Warden et al., 2009). In randomized clinical trials (RCT), PTH greatly accelerated pelvic fracture healing in osteoporotic patients (Peichl et al., 2011). In another RCT, PTH promoted the outcome of periodontal surgery with a significant bone level gain and accelerated osseous wound healing, with little effect on intact alveolar bone (Bashutski et al., 2010). Moreover, we previously reported that PTH therapy for 9 days was enough to increase bone mass in young growing mice (Yamashita et al., 2008). Thus, PTH is highly effective in the host environment where bone formation is dominant, such as osseous wounds and rapidly growing bone. This explains our finding that PTH considerably accelerated hard-tissue healing in wounds. This study also demonstrated that PTH can be used for alveolar ridge preservation, since PTH increased the width of the buccal and lingual bony plates and suppressed vertical bone loss.

Connective tissue maturation was promoted by PTH, as could be seen by the considerably higher quantity of collagen fibers observed in the PTH vs. vehicle wounds. Mechanisms for this enhanced collagen apposition by PTH are unknown, but it could be due to the shift of the soft-tissue environment toward a less inflammatory one by PTH. In this study, PMN numbers were suppressed by PTH at day 7. The degree of PMN infiltration in the PTH group at day 7 was almost equivalent to that in the VC group at day 28. Hence, PTH therapy had a positive impact on the resolution of inflammatory response in the osseous wounds. The anti-inflammatory effect of PTH was reported in a rat model of periodontitis (Barros et al., 2003). That study reported that PTH significantly reduced inflammation in the gingiva and suppressed bone loss. The mechanism of inflammation suppression by PTH is unknown. It might be associated with SDF-1 levels in bone marrow (BM). Neutrophils express stromal-cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) receptors, CXCR4, and increased mobilization of neutrophils is partly regulated by the decreased SDF-1 level in BM (Suratt et al., 2004). As PTH increases BM SDF-1 (Jung et al., 2006), it potentially suppresses peripheral neutrophils. Indeed, Novince and co-workers observed decreased peripheral neutrophils in PRG4-deficient mice on PTH therapy (Novince et al., 2011). Thus, intermittent PTH likely possesses anti-inflammatory and/or pro-resolution effects in osseous wounds. Contrary to findings with intermittent PTH, the literature shows that the function of neutrophils, including migration, phagocytosis, and chemotaxis, is impaired in patients with elevated serum PTH levels (Alexiewicz et al., 1991), indicating that chronically elevated PTH potentially suppresses the immune system. Therefore, the immunomodulatory effects of PTH might depend on the serum PTH level, with continuously elevated PTH suppressing immune function, but intermittent elevation of PTH having an opposite effect.

Teriparatide, a recombinant human parathyroid hormone (1-34), is administered daily by patients injecting into the thigh or abdominal wall. In this study, we explored the practicability of intra-oral PTH injections. Since injections into the buccal and lingual vestibules of the rat mandible were challenging, the maxillary M2 was extracted instead, and the buccal vestibule was used for the injection site. We found that the intra-oral PTH injection was as effective as subcutaneous PTH in promoting extraction socket healing. Therefore, PTH via intra-oral injections is potentially applicable for the promotion of oral osseous wound healing. However, since the intra-oral PTH injection undoubtedly has systemic actions, the optimization of the dose and frequency would be necessary to minimize systemic effects while maximizing the promotion of healing. This would be possible because the PTH anabolic effect is more substantial in osseous wounds than in the intact bone, as discussed above. In this study, osteoclast surfaces were significantly suppressed by subcutaneous PTH injection but were increased by intra-oral PTH injection. The reason for this conflicting outcome on osteoclast surfaces is unknown, but may have contributed to the observed difference in trabecular microarchitecture between the 2 injection routes. Subcutaneous PTH suppression of osteoclast surfaces was associated with thicker trabeculae, demonstrating the anabolic shift from osteoclast to a positive osteoblast balance at this site. Likewise, intra-oral PTH stimulation of osteoclasts was associated with more trabeculae, possibly representing a perforation of existing trabecular structures. Despite these specific changes, there were no observed effects on resulting trabecular bone fill at the healing extraction sites.

In summary, this study showed that: (1) PTH promoted tooth extraction wound healing by enhancing bone fill, suppressing ridge resorption, and promoting collagen apposition in soft tissue; and (2) intra-oral PTH injection effectively promoted tooth extraction socket healing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Chu-Yuan Yeh for technical assistance and Hom-Lay Wang for helpful discussion.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a 2010 award from the ICOI Implant Dentistry Research and Education Foundation, a 2012 award from the Delta Dental Foundation, and an NIDCR award from the National Institutes of Health (DE022327) to LKM.

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

A supplemental appendix to this article is published electronically only at http://jdr.sagepub.com/supplemental.

References

- Alexiewicz JM, Smogorzewski M, Fadda GZ, Massry SG. (1991). Impaired phagocytosis in dialysis patients: studies on mechanisms. Am J Nephrol 11:102-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo MG, Lindhe J. (2009). Ridge alterations following tooth extraction with and without flap elevation: an experimental study in the dog. Clin Oral Implants Res 20:545-549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros SP, Silva MA, Somerman MJ, Nociti FH., Jr (2003). Parathyroid hormone protects against periodontitis-associated bone loss. J Dent Res 82:791-795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashutski JD, Eber RM, Kinney JS, Benavides E, Maitra S, Braun TM, et al. (2010). Teriparatide and osseous regeneration in the oral cavity. N Engl J Med 363:2396-2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellido M, Lugo L, Castañeda S, Roman-Blas JA, Rufián-Henares JA, Navarro-Alarcón M, et al. (2010). PTH increases jaw mineral density in a rabbit model of osteoporosis. J Dent Res 89:360-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HL, McCauley LK. (2013). Parathyroid hormone applications in the craniofacial skeleton. J Dent Res 92:18-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobnig H, Turner RT. (1995). Evidence that intermittent treatment with parathyroid hormone increases bone formation in adult rats by activation of bone lining cells. Endocrinology 136:3632-3638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand T, Ruegsegger P. (1997). A new method for the model-independent assessment of thickness in three-dimensional images. J Microsc 185(Pt 1):67-75. [Google Scholar]

- Jaafar N, Nor GM. (2000). The prevalence of post-extraction complications in an outpatient dental clinic in Kuala Lumpur Malaysia—a retrospective survey. Singapore Dent J 23:24-28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Y, Wang J, Schneider A, Sun YX, Koh-Paige AJ, Osman NI, et al. (2006). Regulation of SDF-1 (CXCL12) production by osteoblasts; a possible mechanism for stem cell homing. Bone 38:497-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroshima S, Go VA, Yamashita J. (2012). Increased numbers of nonattached osteoclasts after long-term zoledronic acid therapy in mice. Endocrinology 153:17-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima A, Shimoji N, Shiomi K, Shimizu S, Moriya H, Einhorn TA, et al. (2002). Mechanisms for the enhancement of fracture healing in rats treated with intermittent low-dose human parathyroid hormone (1-34). J Bone Miner Res 17:2038-2047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novince CM, Koh AJ, Michalski MN, Marchesan JT, Wang J, Jung Y, et al. (2011). Proteoglycan 4, a novel immunomodulatory factor, regulates parathyroid hormone actions on hematopoietic cells. Am J Pathol 179:2431-2442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Ryan FS, Lo JC. (2012). Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with oral bisphosphonate exposure: clinical course and outcomes. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 70:1844-1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peichl P, Holzer LA, Maier R, Holzer G. (2011). Parathyroid hormone 1-84 accelerates fracture-healing in pubic bones of elderly osteoporotic women. J Bone Joint Surg Am 93:1583-1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrokovski J, Massler M. (1967). Ridge remodeling after tooth extraction in rats. J Dent Res 46:222-231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suratt BT, Petty JM, Young SK, Malcolm KC, Lieber JG, Nick JA, et al. (2004). Role of the CXCR4/SDF-1 chemokine axis in circulating neutrophil homeostasis. Blood 104:565-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warden SJ, Komatsu DE, Rydberg J, Bond JL, Hassett SM. (2009). Recombinant human parathyroid hormone (PTH 1-34) and low-intensity pulsed ultrasound have contrasting additive effects during fracture healing. Bone 44:485-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita J, Datta NS, Chun YH, Yang DY, Carey AA, Kreider JM, et al. (2008). Role of Bcl2 in osteoclastogenesis and PTH anabolic actions in bone. J Bone Miner Res 23:621-632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita J, Koi K, Yang DY, McCauley LK. (2010). Effect of zoledronate on oral wound healing in rats. Clin Cancer Res 17:1405-1414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.