Abstract

The functions of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) are primarily mediated and modulated by three families of proteins: the heterotrimeric G proteins, the G-protein coupled receptor kinases (GRKs), and the arrestins1. G proteins mediate activation of second messenger-generating enzymes and other effectors, GRKs phosphorylate activated receptors2, and arrestins subsequently bind phosphorylated receptors and cause receptor desensitization3. Arrestins activated by interaction with phosphorylated receptors can also mediate G protein-independent signaling by serving as adaptors to link receptors to numerous signaling pathways4. Despite their central role in regulation and signaling of GPCRs, a structural understanding of β-arrestin activation and interaction with GPCRs is still lacking. Here, we report the crystal structure of β-arrestin1 in complex with a fully phosphorylated 29 amino acid carboxy-terminal peptide derived from the V2 vasopressin receptor (V2Rpp). This peptide has previously been shown to functionally and conformationally activate β-arrestin15. To capture this active conformation, we utilized a conformationally-selective synthetic antibody fragment (Fab30) that recognizes the phosphopeptide-activated state of β-arrestin1. The structure of the β-arrestin1:V2Rpp:Fab30 complex shows striking conformational differences in β-arrestin1 compared to its inactive conformation. These include rotation of the amino and carboxy-terminal domains relative to each other, and a major reorientation of the “lariat loop” implicated in maintaining the inactive state of β-arrestin1. These results reveal, for the first time at high resolution, a receptor-interacting interface on β-arrestin, and they suggest a potentially general molecular mechanism for activation of these multifunctional signaling and regulatory proteins.

Binding of β-arrestins to phosphorylated GPCRs is thought to involve two types of interaction between a receptor and a β-arrestin molecule6. A phosphate sensor engages the phosphorylated carboxy terminus or third intracellular loop of the receptor, and a conformational sensor recognizes the agonist-induced, active conformation of the core of the receptor (Fig. 1a). Using mass spectrometry-based conformational mapping, we have previously used a V2 vasopressin receptor-derived phosphopeptide (V2Rpp) to investigate activation of β-arrestins1 and 25,7. Binding to V2Rpp recapitulates functionalities of receptor activated β-arrestins, such as enhanced clathrin binding5. Thus, we reasoned that crystallographic study of a complex of β-arrestin1 with V2Rpp would provide insight into the mechanisms of receptor-mediated β-arrestin activation. However, well-ordered crystals of β-arrestin1 bound to V2Rpp could not be obtained. This is presumably due to the significant conformational flexibility of activated arrestin molecules, as was recently determined for visual arrestin by NMR spectroscopy8. Given the success of antigen binding fragments (Fabs)9 and nanobodies10 in stabilizing particular GPCR conformations, we sought to identify and characterize conformationally-selective Fabs that stabilize the V2Rpp bound, active conformation of β-arrestin1.

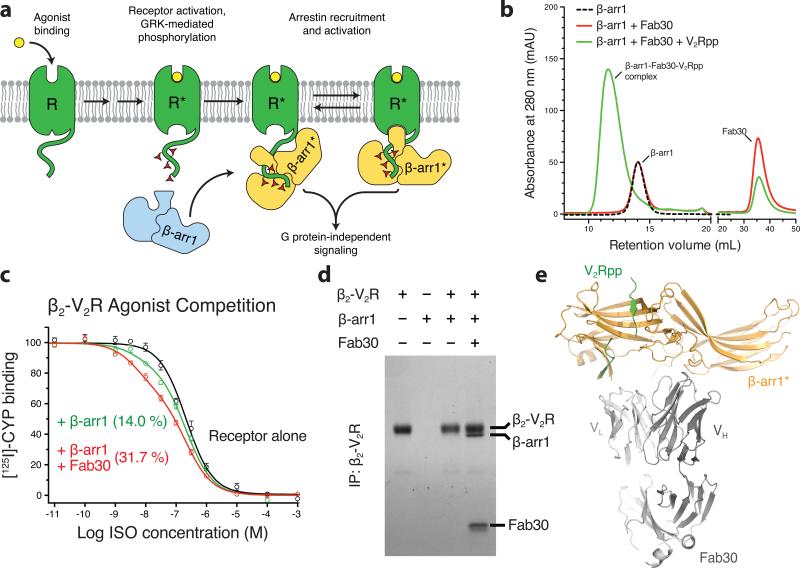

Figure 1. Fab30 specifically recognizes and stabilizes an active state of β-arrestin1.

a, G protein coupled receptors are phosphorylated following activation, leading to the binding of arrestins. Interactions between the phosphorylated receptor and β-arrestin1 lead to β-arrestin1 activation and the subsequent blockade of G protein signaling and initiation of β-arrestin1 signaling pathways. b, Interaction between β-arrestin1 and Fab30 requires the presence of V2Rpp in a size exclusion assay. c, The formation of a complex between a GPCR and β-arrestin allosterically leads to an enhanced affinity of agonist for the receptor, termed the “high agonist affinity state.” Therefore, the fraction of receptor in the high agonist affinity state reflects the extent of complex formation between receptor and β-arrestin. In a radioligand competition binding assay using 125I-cyanopindolol as the probe and the agonist isoproterenol (Iso) as the competitor, β-arrestin1 alone shifts a small portion (14%) of receptors into the high agonist affinity state. Fab30 significantly amplifies this effect (31%) (n=3, p<0.0001 in F test). d, In a pull-down assay, phosphorylated β2-V2R chimera shows appreciable binding to β-arrestin1 only in the presence of Fab30. e, Overall structure of the β-arrestin1:V2Rpp:Fab30 complex.

We utilized a minimalist synthetic Fab phage display library11 to select several high affinity Fabs that selectively recognize the β-arrestin1:V2Rpp complex (Fig. S1). One of these, Fab30, displays striking selectivity for the activated conformation of β-arrestin1 induced by V2Rpp (Fig. 1b). In order to ensure that Fab30 stabilizes a physiologically relevant conformation of β-arrestin1, we investigated whether this Fab could facilitate interaction between a receptor and β-arrestin1. Here, we used the previously described chimeric receptor β2-V2R which has an identical carboxy terminus to V2Rpp, and which also has unaltered ligand binding characteristics compared to the wild-type β2 adrenergic receptor (β2AR)12. Complexes of GPCRs with either G proteins or β-arrestins display an enhanced affinity for agonists due to the allosteric interactions among the agonist, the receptor and the transducer (G protein or β-arrestin)13,14. Addition of exogenous β-arrestin1 to the membranes containing phosphorylated β2-V2R resulted in a small fraction of the receptor in high agonist affinity state compared to receptor alone (Fig. 1c). Addition of Fab30 significantly increased the percentage of receptors in the high affinity state. Furthermore, a direct physical stabilization of the receptor:β-arrestin1 complex by Fab30 was revealed by co-immunoprecipitation (Fig. 1d). Here, we present a 2.6 Å crystal structure of the β-arrestin1:V2Rpp:Fab30 complex (Fig. 1e).

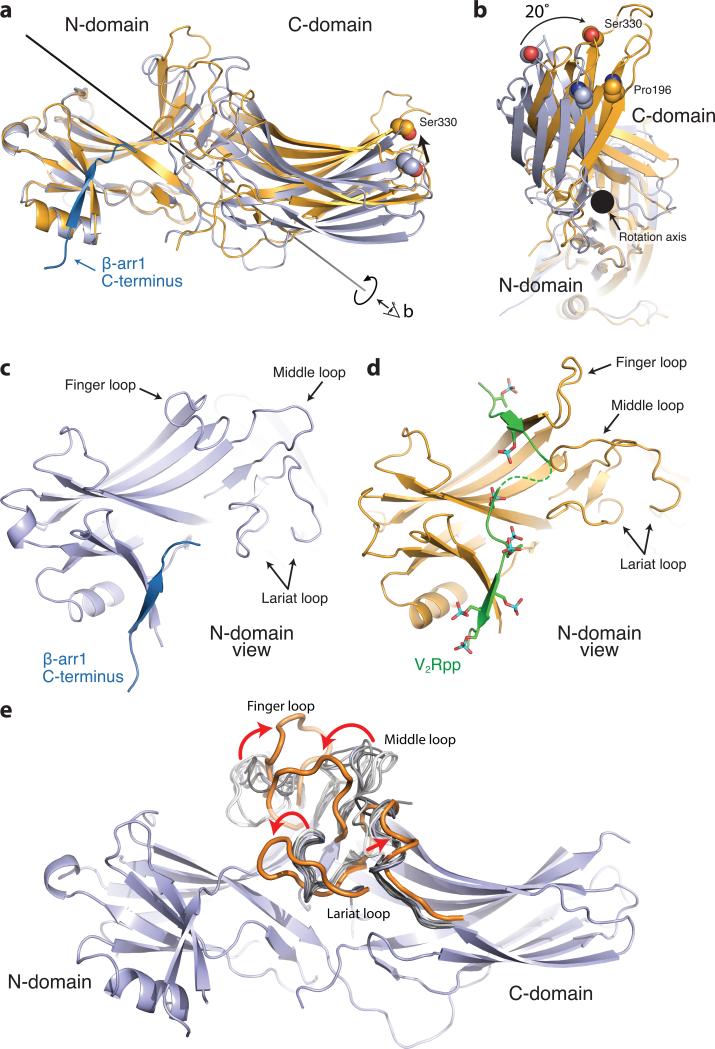

The overall structure of activated β-arrestin1 exhibits a wide variety of pronounced structural changes compared to previously determined inactive state structures. Most notably, the N- and C-domains of β-arrestin1 undergo a substantial twist relative to one another (Fig. 2a,b), with a 20° rotation around a central axis. The V2Rpp binds to the N-domain at a similar location to the β-arrestin1 carboxy terminus in inactive structures and makes extensive contacts, primarily through charge-charge interactions of V2Rpp phosphates with β-arrestin1 arginine and lysine side chains (compare Fig. 2c with Fig. 2d, 3d).

Figure 2. Conformational changes associated with β-arrestin1 activation.

The structures of inactive β-arrestin1 (PDB ID: 1G4M chain A, light blue) and active β-arrestin1 (gold) were aligned on the N-domains. The β-arrestin1 carboxy terminus is highlighted in dark blue. a, A substantial rotation and translation of the C-domain relative to the N-domain occurs upon activation. The rotation axis is indicated as a solid black line. b, View of C-domain rotation along the axis. c, N-domain of inactive arrestin, highlighting important regions. d, Active β-arrestin1 in the same orientation, showing V2Rpp in green. Phosphorylated residues are highlighted as sticks. e, The overall structure of inactive β-arrestin1 (PDB ID: 1G4M, chain A), with loops from all inactive β-arrestin1 structures superimposed (grey loops). The active conformation of these loops (orange loops) deviates from all inactive structures.

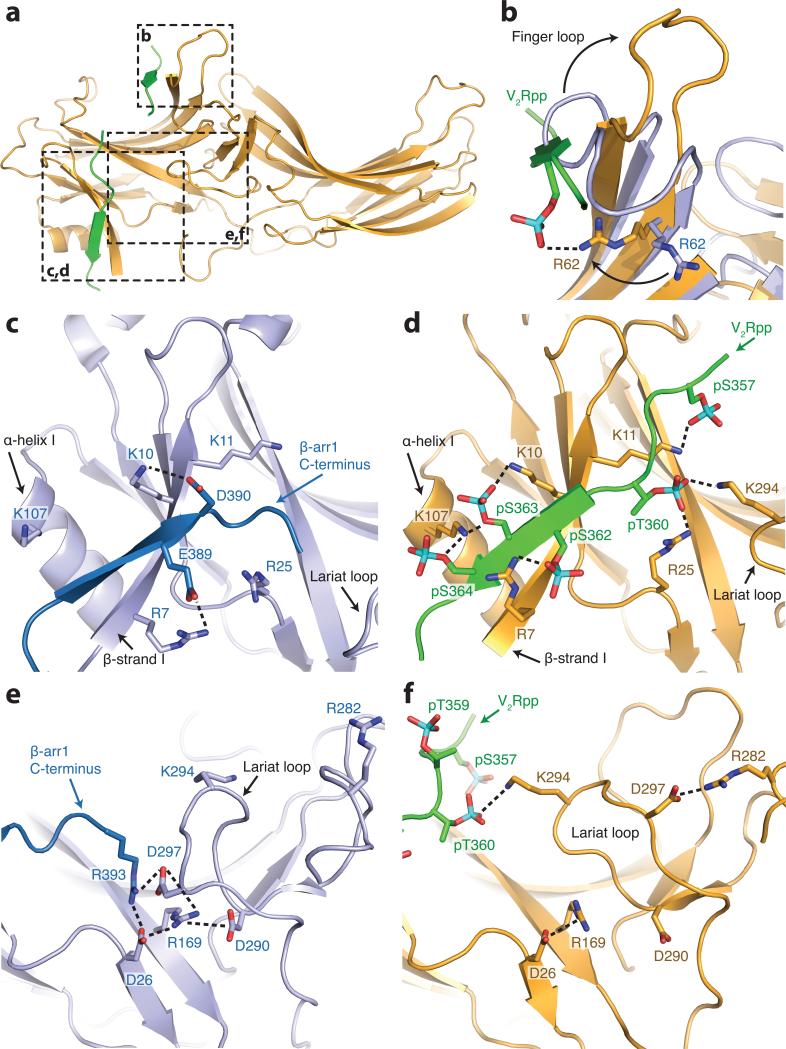

Figure 3. V2Rpp interactions with β-arrestin1.

a, Overall view of β-arrestin1, with regions of interest in boxes. Select charge-charge contacts are shown in dotted lines. b, V2Rpp (green) displaces the inactive finger loop (light blue), causing it to adopt an extended conformation in the active state (gold). c, In the inactive conformation, the β-arrestin1 carboxy-terminal β strand (dark blue) lies along the N-domain in the “three element” interaction network. d, Upon activation, this strand is displaced by the carboxy terminus of the V2Rpp, which engages in extensive charge-charge interactions through phosphorylated residues. e, The “polar core” of β-arrestin1 is thought to be a critical stabilizer of the inactive state. f, Upon V2Rpp binding, the carboxy-terminal strand residue Arg393 is displaced, and its interaction partner D297 undergoes a large movement together with the rest of the lariat loop.

This binding mode is consistent with previous limited proteolysis studies that revealed protection of the N-domain of β-arrestin1 in the presence of V2Rpp5. Additionally, crosslinking experiments on the β-arrestin1:V2Rpp complex in the absence of Fab30 show that the amino terminus of the V2Rpp is in close proximity to K77, consistent with our structure (Fig. S2). Like the β-arrestin1 carboxy terminus, V2Rpp binds β-arrestin1 by extending the N-domain β-sandwich fold. Unlike the carboxy terminus, however, V2Rpp binds as an anti-parallel β-strand. This binding mode may serve as a general mechanism by which arrestins recognize the phosphorylated loops and carboxy-terminal tails of receptors.

In addition to the large interdomain rearrangement, the N-domain and central loops show large structural changes associated with β-arrestin1 activation. Several loops have been implicated in various aspects of β-arrestin activation and receptor interaction15. These include the “finger loop” (residues 63-75), the “middle loop” (residues 129-140) and the “lariat loop” (residues 274-300). Each of these loops exhibits activation-dependent conformational changes (Fig. 2c-e). Comparison of these loops with inactive structures of β-arrestin1 shows the considerable flexibility in each loop in the inactive conformation, but a more marked change in conformation upon β-arrestin activation (Fig. 2e). The crystal structure reveals that the V2Rpp occludes the inactive conformation of the finger loop, which has been shown to be important for arrestin discrimination between active and inactive GPCRs16. V2Rpp may stabilize an extended conformation of this loop to facilitate contact with the receptor core (Fig. 3b). It is noteworthy that the finger and middle loops above are not at the β-arrestin1:Fab30 interaction interface (Fig. S3), and therefore, the conformational reorientation observed for these loops most likely reflects activation-dependent changes in β-arrestin1. However, finger loop residues 63-67 and lariat loop residues 285-287 engage in crystal lattice contacts (Fig. S4), so some caution is warranted in the interpretation of conformational changes in these regions.

Two major sets of intramolecular interactions have been proposed to constrain arrestins in an inactive conformation: the three-element interaction and the polar-core interaction. The three element interaction consists of interactions between β-strand I, α-helix I and the carboxy terminus of arrestin17. Disruption of this interaction by mutagenesis yields arrestins that are partially phosphorylation-independent in their binding to receptor17, suggesting a key role for this interaction network in recognizing phosphorylated receptors. The crystal structure of β-arrestin1 shows that two well-conserved residues, K10 and K11 on β-strand I, make charge-charge interactions with phosphorylated residues pS363 and pS357 of V2Rpp (Fig 3d). Indeed, mutagenesis of the corresponding lysines in visual arrestin significantly decreases binding to phosphorylated, active rhodopsin, suggesting that these residues serve as essential phosphate recognition elements17. Furthermore, previous limited proteolysis studies have indicated that the carboxy terminus of both visual and β-arrestins is released upon activation as part of the disruption of the three element interaction5,18,19. Consistent with this model, we observe that the β-arrestin1 carboxy terminus is displaced by the V2Rpp (Fig. 3c,d). The β-arrestin1 carboxy terminus contains a clathrin binding site that has been previously characterized to be important for GPCR internalization20. Hence, displacement of the carboxy terminus upon phosphopeptide binding and β-arrestin1 activation is likely an important contributor to clathrin-mediated GPCR internalization. In comparison to previous models, however, binding of V2Rpp and displacement of the carboxy terminus does not dramatically alter the secondary structure of β-strand I. While we observe abundant charge-charge interactions between β-arrestin1 and V2Rpp, it is noteworthy that neither the specific sequence of the phosphorylation sites nor the net number of phosphates is conserved among various receptors. Therefore, it remains to be seen how β-arrestins fine-tune their interaction with such a large number of receptors.

The second constraint that stabilizes the inactive conformation of arrestins is the polar core18, consisting of five interacting charged residues: D26, R169, D290, D297, and R393. Disruption of the polar core by mutagenesis yields phosphorylation-independent mutants of both visual arrestin and β-arrestin117,21. Charge reversal of R169 or D290 in β-arrestin1 (R175 and D290 in visual arrestin) disrupts this interaction network, yielding arrestins that can bind non-phosphorylated, activated receptors. Based on these studies, R169 was previously proposed to be a critical phosphate sensor in β-arrestin1, and disruption of the polar core was proposed to be required for β-arrestin1 activation21. Contrary to this model, R169 does not make any direct contacts with V2Rpp phosphates, suggesting that direct interaction between R169 and receptor phosphates is not required for arrestin activation (Fig 3e,f). However, binding of V2Rpp does disrupt the polar core. V2Rpp binding to β-arrestin1 displaces the arrestin carboxy terminus, and in doing so, removes R393 from the polar core. Residues D290 and D297 also lose interactions within the polar core, and this is accompanied by a dramatic twisting of the lariat loop, which contains both D290 and D297. Therefore, it is possible that the disruption of the polar core is driven by the excess negative charge in this region following displacement of the arrestin carboxy terminus residue R393. Interestingly, the side chain of K294, a residue within the lariat loop, flips toward the N-domain upon activation and engages pT360. It is possible that K294 recognition of phosphates provides an additional driving force for lariat loop rearrangement, and may therefore stabilize β-arrestin1 in an active conformation. This observation in the crystal structure is consistent with crosslinking experiments, which reveal the disappearance of an intra-peptide crosslink between K292 and K294 in the presence of V2Rpp (Fig. S5), indicating that V2Rpp induces a conformation like that seen in the crystal structure even in the absence of Fab30.

While domain rearrangement upon arrestin activation has been previously proposed, the observed 20° twisting of the N- and C- domains of β-arrestin1 upon activation is unanticipated. Biochemical studies have shown that sequential deletion of the visual arrestin hinge region connecting the N- and C- domains results in a progressive decrease in the ability of arrestin to bind phosphorylated, light-activated rhodopsin. This suggests a requirement for relative movement of the two domains for efficient interaction with activated receptors22. However, the twisting motion observed here stands in contrast to the “clamshell” hypothesis advanced previously23. Considering the large number of interaction partners of β-arrestins during cellular signaling24, it is tempting to speculate that the twisting movement of the two domains upon arrestin activation may expose interaction interfaces with such binding partners.

Recent NMR and double electron-electron resonance (DEER) studies have assessed the conformational changes induced in visual arrestin upon interaction with phosphorylated, light-activated rhodopsin8,25. Intriguingly, NMR spectroscopy of activated visual arrestin revealed significant line broadening attributed to intermediate timescale conformational dynamics over the entire arrestin molecule8. Within such an ensemble of activated arrestin conformations, Fab30 likely stabilizes a conformation of β-arrestin1 that preferentially binds activated GPCRs. Furthermore, distance restraints for activated visual arrestin derived from DEER experiments are highly consistent with the active structure of β-arrestin1 presented here (Fig. S6). Most notably, the large conformational change observed for the middle loop by DEER spectroscopy upon binding light-activated, phosphorylated rhodopsin is also evident in the crystal structure of activated β-arrestin1. Given the importance of this region in maintaining the inactive conformation of visual arrestin, the agreement in conformational changes within arrestin suggests that the V2Rpp bound, active conformation of β-arrestin1 presented here represents a similar state to that of arrestin in complex with a phosphorylated, activated GPCR. This further suggests that the conformational changes associated with activation and receptor binding are conserved throughout the arrestin family. However, the binding stoichiometry between GPCRs and arrestins still remains to be fully established. Recent biochemical studies have suggested that two rhodopsin molecules may simultaneously bind one arrestin26. The extensive and specific contacts between V2Rpp and the β-arrestin1 N-domain likely preclude another receptor carboxy terminus from binding β-arrestin1. However, it is possible that an arrestin molecule bound to the phosphorylated carboxy terminus of a receptor could interact with the 7TM core of another receptor. Additional data, including a crystal structure of a GPCR:β-arrestin complex, will be required to clarify this.

In summary, we present here the first structure of an activated arrestin bound to the phosphorylated carboxy terminus of a GPCR. The structure not only provides the atomic details of a potentially general GPCR-β-arrestin interaction interface, but also offers novel insights into the activation process of arrestins, and reveals a large interdomain twisting associated with activation. These findings will facilitate future efforts to understand the structural basis for β-arrestin activation and signaling. Such studies may ultimately yield insight into how GPCRs achieve such a large breadth of signaling complexity.

ONLINE METHODS

Purification of β-arrestin1

Full-length β-arrestin1 was purified from E. coli as described previously5. Briefly, GST-tagged rat β-arrestin1 in the pGEX4T vector was transformed into BL21(DE3) cells, large scale expression cultures were grown in Terrific Broth, and induced with 1 mM IPTG for 16 hr at 16 °C. Cell pellets were lysed in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM PMSF and 2 mM DTT using a micro fluidizer, and the lysate was bound to glutathione sepharose at 4 °C for 2 hr. Beads were washed in lysis buffer and β-arrestin1 was eluted by overnight incubation with thrombin at 4 °C. β-arrestin1 was then purified with a HiTrap Q column and eluted by a linear gradient of NaCl. Peak fractions were pooled and purified protein was dialyzed in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.4 and 150 mM NaCl.

Selection and characterization of Fab

The phage library was panned against biotinylated β-arrestin1 bound to V2Rpp and immobilized on streptavidin beads. Beads were washed three times and bound phages were amplified by infecting E. coli XL-1 blue cells. Amplified phage were precipitated and used for a second and third round of panning. To select against Fabs that bind to the inactive conformation of β-arrestin1, beads coated with the β-arrestin1:V2Rpp complex were first incubated with phage and then with 1 μM non-biotinylated β-arrestin1. Subsequently, phage were eluted with dithiothreitol (DTT) and resulting clones were used for single point ELISA to test their selectivity towards β-arrestin1 bound to V2Rpp. ELISA positive clones were sequenced and further characterized.

Selectivity of Fabs towards V2Rpp bound β-arrestin1 conformation

β-arrestin1 was incubated with either non-phosphorylated V2 vasopressin peptide (V2Rnp) or V2Rpp in a 1:3 molar ratio for 30 min at 25 °C. Subsequently, purified Fabs were added at a 1:2 molar ratio with β-arrestin1 and incubated for additional 30 min at 25 °C. Then, pre-washed Protein A beads (Pierce) were added to the reactions and incubated for 30 min at 25 °C. The final concentration of β-arrestin1 in the binding reaction was 10 nM. Beads were washed 4 times with 1 ml buffer (20 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl) and proteins were eluted with SDS-PAGE gel loading buffer. The eluted proteins were run on a 4-20% SDS-PAGE gel. Fab30 displayed the greatest difference in its ability to co-immunoprecipitate β-arrestin1 between V2Rnp and V2Rpp and was therefore chosen for further characterization (Reis & Lefkowitz, manuscript in preparation).

Radioligand binding

Sf9 insect cells were co-infected with baculovirus encoding an N-terminal FLAG tagged β2-V2R (a chimeric receptor with β2AR residues 1 to 341 and V2 vasopressin receptor residues 328 through 372) and GRK2-CAAX (GRK2 with a membrane tethering prenylation signal). Following viral infection for 72 hours at 27 °C, cells were incubated with 10 μM isoproterenol at 37 °C for 15 min to induce receptor phosphorylation. Subsequently, the cells were washed and membranes were prepared and flash frozen. Membranes were extensively washed in order to remove isoproterenol used for receptor phosphorylation. For radioligand binding, membranes were incubated with 60 pM [125I] cyanopindolol (GE Healthcare Lifescience) in radioligand binding buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 50 mM potassium acetate, 0.5 mM magnesium chloride, 1 mM ascorbic acid) with varying concentrations of freshly prepared isoproterenol. Binding reactions were performed in parallel, with 1 μM β-arrestin1 (residues 1-393) incubated either in the presence or absence of 10 μM Fab30. Binding reactions were incubated for 90 min at 27 °C, followed by rapid harvesting on a GF-B filter and scintillation counting in a Packard gamma counter. Competition binding data were analyzed by a non-linear curve-fitting procedure where low and high affinity values were computed globally using a two-site binding model (GraphPad Prism). The F-test was used to test whether Fab30 significantly altered the amount of β2-V2R coupled to β-arrestin.

Effect of Fab30 on β2-V2R:β-arrestin1 interaction

Fab30 was expressed and purified as described previously27. β2-V2R was expressed in Sf9 cells and purified as described previously28. Purified, phosphorylated β2-V2R was prepared bound to the potent agonist β2AR agonist BI-16710710 and incubated at a concentration of 1 μM with 3 μM β-arrestin1 with and without Fab30 at 25 °C for 2 hours in a buffer comprised of 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01% MNG (lauryl maltose neopentyl glycol). Subsequently, β2-V2R was immunoprecipitated using M1 FLAG antibody beads. Beads were washed and protein was eluted with 5 mM EDTA and 0.25 mg/ml FLAG peptide and elution fractions were analyzed on a 4-20% SDS-PAGE gel and stained with Coomassie.

Preparation of β-arrestin1:V2Rpp:Fab30 complex, crystallization, and structure determination

β-arrestin1 (20 μM) was incubated with V2Rpp (27 μM) for 30 min at 25 °C. An excess of Fab30 was added and the complex was incubated for 1 hour at 25 °C. The β-arrestin1:V2Rpp:Fab30 complex was purified from excess Fab30 and V2Rpp by size exclusion chromatography in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, and 1 mM TCEP. The purified complex was concentrated to 8 mg/ml using a centrifugal concentrator (Vivaspin, GE Healthcare). Crystals were grown in hanging drops containing 1 μL of complex solution and 0.5 μL of a well solution composed of 17% PEG 3350, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5, and 0.2 M L-proline. Drops were stored at 20 °C and crystals appeared within 24 hours and grew to full size within 3 days (Fig. S4). Crystals were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen after a 30 second soak in 19% PEG 3350, 0.1 M HEPES pH 7.5, 0.2 M L-proline, and 20% ethylene glycol.

Diffraction data were collected at the Advanced Photon Source GM/CA-CAT beamline 23ID-D. Although typical crystals grew to over 300 μm in two dimensions, and over 100 μm in the third dimension, we utilized a 10 μm-sized beam to collect multiple full datasets from the highest quality regions of the crystal. A full dataset from the single best region of the crystal was indexed, integrated, and scaled with HKL-200029. The structure of the complex was solved by molecular replacement using Phaser30. Due to the conformational changes observed for β-arrestin1, it proved necessary to first search for Fab30 (PDB ID: 3EFF; Fab2, with the complementary determining regions omitted, was used as a search model for Fab30)31, followed by only the C-domain of β-arrestin1 (PDB ID: 1JSY)32. A subsequent search for the N-domain of β-arrestin1 failed in multiple attempts; the N-domain was then manually placed to fit the electron density. A significant decrease in Rfree upon rigid body refinement of the N-domain provided confidence in the final molecular replacement solution. The resulting model was then iteratively refined by building regions of β-arrestin1, V2Rpp, and Fab30 in Coot33 and refining in Phenix34. We utilized translation libration screw-motion (TLS) refinement with groups defined within Phenix34. For the V2Rpp, the amino-acid register was determined by the strong electron density resulting from electron-rich phosphates on phosphoserine and phosphothreonine residues. As shown in Fig. S7, the electron density for the V2Rpp was clear, permitting confident placement of most side chains. We used MolProbity35 to assess statistics for the final model of the β-arrestin1:V2Rpp:Fab30 complex. Supplementary table 1 outlines statistics for data collection and refinement. Figures were prepared in PyMOL36 and secondary structure was assigned using the DSSP algorithm37. Domain rotation was measured and analyzed with DynDom38.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Darrell Capel for excellent technical assistance and Victoria Ronk, Donna Addison and Quivetta Lennon for administrative and secretarial support. We thank Drs. Seungkirl Ahn and Laura Wingler for critical reading of the manuscript. We acknowledge support from the Stanford Medical Scientist Training Program and the American Heart Association (A.M.), from the National Science Foundation (A.C.K.), from the National Institutes of Health Grants NS028471 (B.K.K), HL16037 and HL70631 (R.J.L.), GM072688 and GM087519 (A.A.K & S.K.), HL 075443 (K.H.X) and from the Mathers Foundation (B.K.K. and W.I.W.). R.I.R is supported by a post-doctoral fellowship from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior – CAPES. R.J.L. is an investigator with the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Author Information Coordinates and structure factors for the β-arrestin1:V2Rpp:Fab30 complex are deposited in the Protein Data Bank (accession code 4JQI).

The authors declare no competing financial interests. Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of this article at www.nature.com/nature.

Author Contributions A.K.S conceived the project, designed the Fab selection strategy, selected and characterized Fab30, established and optimized complex formation and purification conditions, prepared protein for crystallization trials and supervised the experiments related to the biochemical characterization of the complex. A.M. purified the complex, performed crystallography trials, and grew crystals. A.M. and A.C.K. collected and processed diffraction data, and solved and refined the structure with supervision from W.I.W. R.I.R assisted with advanced Fab characterization and optimized complex formation. W.C.T. assisted with Fab selection and preliminary characterization. K.H.X. performed and analyzed the crosslinking experiments. D.P.S. performed and analyzed radioligand binding experiments. L.Y.H. assisted with functional characterization of the complex. P.T.S. expressed and purified the receptor. S.U., M.P., A.K., S.K. and A.A.K. generated and provided the phage display library and the screening protocol and helped with the initial phase of Fab selection. D.H. performed the comparison of the structural model to prior EPR data. A.K.S., A.M. and A.C.K. made figures. A.K.S., A.M., A.C.K., B.K.K., and R.J.L. wrote the manuscript. B.K.K. and R.J.L. supervised the overall research.

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Pierce KL, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:639–650. doi: 10.1038/nrm908. doi:10.1038/nrm908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hepler JR, Gilman AG. G proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 1992;17:383–387. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(92)90005-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freedman NJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1996;51:319–351. discussion 352-313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lefkowitz RJ, Shenoy SK. Transduction of receptor signals by beta-arrestins. Science. 2005;308:512–517. doi: 10.1126/science.1109237. doi:10.1126/science.1109237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nobles KN, Guan Z, Xiao K, Oas TG, Lefkowitz RJ. The active conformation of beta-arrestin1: direct evidence for the phosphate sensor in the N-domain and conformational differences in the active states of beta-arrestins1 and -2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21370–21381. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611483200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M611483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV. The structural basis of arrestin-mediated regulation of G-protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;110:465–502. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.09.008. doi:10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiao K, Shenoy SK, Nobles K, Lefkowitz RJ. Activation-dependent conformational changes in {beta}-arrestin 2. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:55744–55753. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409785200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M409785200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhuang T, et al. Involvement of distinct arrestin-1 elements in binding to different functional forms of rhodopsin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215176110. doi:10.1073/pnas.1215176110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rasmussen SGF, et al. Crystal structure of the human beta(2) adrenergic G-protein-coupled receptor. Nature. 2007;450:383–U384. doi: 10.1038/nature06325. doi:Doi 10.1038/Nature06325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasmussen SGF, et al. Structure of a nanobody-stabilized active state of the beta(2) adrenoceptor. Nature. 2011;469:175–180. doi: 10.1038/nature09648. doi:Doi 10.1038/Nature09648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fellouse FA, et al. High-throughput generation of synthetic antibodies from highly functional minimalist phage-displayed libraries. Journal of molecular biology. 2007;373:924–940. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.005. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oakley RH, Laporte SA, Holt JA, Barak LS, Caron MG. Association of beta-arrestin with G protein-coupled receptors during clathrin-mediated endocytosis dictates the profile of receptor resensitization. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32248–32257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Lean A, Stadel JM, Lefkowitz RJ. A ternary complex model explains the agonist-specific binding properties of the adenylate cyclase-coupled beta-adrenergic receptor. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:7108–7117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gurevich VV, Pals-Rylaarsdam R, Benovic JL, Hosey MM, Onorato JJ. Agonist-receptor-arrestin, an alternative ternary complex with high agonist affinity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28849–28852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.28849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han M, Gurevich VV, Vishnivetskiy SA, Sigler PB, Schubert C. Crystal structure of beta-arrestin at 1.9 A: possible mechanism of receptor binding and membrane Translocation. Structure. 2001;9:869–880. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00644-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hanson SM, et al. Differential interaction of spin-labeled arrestin with inactive and active phosphorhodopsin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:4900–4905. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600733103. doi:10.1073/pnas.0600733103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vishnivetskiy SA, et al. An additional phosphate-binding element in arrestin molecule. Implications for the mechanism of arrestin activation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:41049–41057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007159200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M007159200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vishnivetskiy SA, et al. How does arrestin respond to the phosphorylated state of rhodopsin? The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:11451–11454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.17.11451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palczewski K, Buczylko J, Imami NR, McDowell JH, Hargrave PA. Role of the carboxyl-terminal region of arrestin in binding to phosphorylated rhodopsin. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1991;266:15334–15339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goodman OB, Jr., et al. Beta-arrestin acts as a clathrin adaptor in endocytosis of the beta2-adrenergic receptor. Nature. 1996;383:447–450. doi: 10.1038/383447a0. doi:10.1038/383447a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovoor A, Celver J, Abdryashitov RI, Chavkin C, Gurevich VV. Targeted construction of phosphorylation-independent beta-arrestin mutants with constitutive activity in cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:6831–6834. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.6831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vishnivetskiy SA, Hirsch JA, Velez MG, Gurevich YV, Gurevich VV. Transition of arrestin into the active receptor-binding state requires an extended interdomain hinge. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277:43961–43967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206951200. doi:DOI 10.1074/jbc.M206951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gurevich VV, Gurevich EV. The molecular acrobatics of arrestin activation. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2004;25:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.12.008. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao K, et al. Functional specialization of beta-arrestin interactions revealed by proteomic analysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:12011–12016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704849104. doi:10.1073/pnas.0704849104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim M, et al. Conformation of receptor-bound visual arrestin. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:18407–18412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1216304109. doi:10.1073/pnas.1216304109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sommer ME, Hofmann KP, Heck M. Distinct loops in arrestin differentially regulate ligand binding within the GPCR opsin. Nat Commun. 2012;3:995. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2000. doi:10.1038/ncomms2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rizk SS, et al. Allosteric control of ligand-binding affinity using engineered conformation-specific effector proteins. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2011;18:437–442. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2002. doi:10.1038/nsmb.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobilka BK. Amino and Carboxyl Terminal Modifications to Facilitate the Production and Purification of a G Protein-Coupled Receptor. Analytical Biochemistry. 1995;231:269–271. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1533. doi:10.1006/abio.1995.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Macromolecular Crystallography, Pt A. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. doi:Doi 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. Journal of Applied Crystallography. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. doi:10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uysal S, et al. Crystal structure of full-length KcsA in its closed conformation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:6644–6649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810663106. doi:10.1073/pnas.0810663106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milano SK, Pace HC, Kim YM, Brenner C, Benovic JL. Scaffolding functions of arrestin-2 revealed by crystal structure and mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 2002;41:3321–3328. doi: 10.1021/bi015905j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. doi:10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD. A robust bulk-solvent correction and anisotropic scaling procedure. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2005;61:850–855. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905007894. doi:10.1107/S0907444905007894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. doi:10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schrodinger L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System v.1.3r1. 2010.

- 37.Kabsch W, Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. doi:10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hayward S, Kitao A, Berendsen HJ. Model-free methods of analyzing domain motions in proteins from simulation: a comparison of normal mode analysis and molecular dynamics simulation of lysozyme. Proteins. 1997;27:425–437. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(199703)27:3<425::aid-prot10>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.