Abstract

The non-metabolizable fluorescent glucose analogue 6-(N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino)-2-deoxyglucose (6-NBDG) is increasingly used to study cellular transport of glucose. Intracellular accumulation of exogenously applied 6-NBDG is assumed to reflect concurrent gradient-driven glucose uptake by glucose transporters (GLUTs). Here theoretical considerations are provided that put this assumption into question. In particular, depending on the microscopic parameters of the carrier proteins, theory proves that changes in glucose transport can be accompanied by opposite changes in flow of 6-NBDG. Simulations were carried out applying the symmetric four-state carrier model on the GLUT1 isoform, which is the only isoform whose kinetic parameters are presently available. Results show that cellular 6-NBDG uptake decreases with increasing rate of glucose utilization under core-model conditions supported by literature, namely where the transporter is assumed to work in regime of slow reorientation of the free-carrier compared to the ligand-carrier complex. In order to observe an increase of 6-NBDG uptake with increasing rate of glucose utilization, and thus interpret 6-NBDG increase as surrogate of glucose uptake, the transporter must be assumed to operate in regime of slow ligand-carrier binding, a condition that is currently not supported by literature. Our findings suggest that the interpretation of data obtained with NBDG derivatives is presently ambiguous and should be cautious because the underlying transport kinetics are not adequately established.

Keywords: NBDG, glucose, GLUT, astrocytes, four-state carrier model

Introduction

Most mammalian cells use glucose for energy metabolism and as precursor for the synthesis of many important biological molecules. Transport of glucose is mediated by a family of ubiquitous integral membrane uniporter carriers named glucose transporter (GLUT) proteins (reviewed by Simpson et al. 2007). The fluorescent glucose analogue 6-(N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino)-2-deoxyglucose (6-NBDG) was introduced as a tool to quantify cell hexose uptake (Speizer et al. 1985). Most of the research using NBDG for monitoring glucose uptake in normal (i.e. non-cancer) cells has so far focused on insulin-sensitive cells. Such studies detected insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in cultured muscle cells, monocytes, adipocytes or hepatocytes, and have conversely produced conflicting results about the effect of accelerated glucose transport on intracellular NBDG accumulation (Dimitriadis et al. 2005, Zou et al. 2005, Leira et al. 2002, Jung et al. 2011). These cell types all express the insulin-sensitive GLUT4 isoform, therefore results obtained by studies conducted on GLUT4-expressing cells cannot be extrapolated to provide insights on 6-NBDG uptake by tissues where GLUT4 is not expressed, such as cerebral cortex (Simpson et al. 2007). In the following we will focus on cortical astrocytes expressing preferentially GLUT1 isoform. This choice is explained by the availability of microscopic carrier parameters for cerebral GLUT1 as well as by the fact that 6-NBDG has been recently utilized to investigate astrocytic glucose uptake during brain stimulation (see below).

In brain tissue, the relatively high (typically millimolar, mM) glucose level maintains the saturation of hexokinase (HK) under basal as well as activated conditions (Qutub & Hunt 2005 and references therein). Indeed, GLUTs are not rate-limiting for metabolism of glucose because the affinity of HK for glucose (Km=0.05 mM) is substantially higher compared with that of GLUTs (Km=5–10 mM) (Gruetter et al. 1992, Simpson et al. 2007). Therefore, it is the rate of glucose phosphorylation that controls net uptake of glucose. Contrary to glucose, 6-NBDG is not metabolized, yet it competes with glucose for the same carrier binding site, although a fraction of 6-NBDG transport possibly is non GLUT-mediated (see Mangia et al. 2011). Previous studies regarding the non-metabolizable glucose analogue 3-O-methylglucose showed that brain/plasma (or intracellular/extracellular) distribution ratio for methylglucose follows tissue glucose content (see Nakanishi et al. 1996 and references therein). Specifically, when metabolism is either stimulated or reduced (for a fixed plasma glucose level) the glucose concentration and methylglucose distribution ratio either decreases or increases. In agreement with these arguments, it was recently pointed out that the kinetics of 6-NBDG transport might or might not be governed by the same supply-demand balance of glucose depending on the relation between intracellular/extracellular sugar levels and metabolic demand (Dienel 2012). Therefore, to correctly interpret fluorescence data it is important to evaluate to what extent the transport of 6-NBDG actually reflects the cellular metabolism of glucose.

Assays of basal cerebral glucose transport using NBDG showed diffusely distributed fluorescence in the parenchyma of the mouse hippocampus (Shimada et al. 1994, Itoh et al. 2004). Accumulation of NBDG in both neurons and astrocytes was also demonstrated in vitro (Aller et al. 1997). Glutamate-induced changes in uptake of NBDG was then investigated in hippocampal astrocyte-enriched cultures (Loaiza et al. 2003) as well as neuron-astrocyte co-cultures (Porras et al. 2004). These studies reported very rapid enhanced astrocytic and inhibited neuronal NBDG transport upon stimulation by glutamate. Importantly, the same group failed to observe any short-term increase of astrocytic glycolytic rate in response to glutamate using DNA-encoded Förster resonance energy-transfer based glucose nanosensor (Bittner et al. 2011). Using the FRET based nanosensor, their subsequent study actually showed nearly instantaneous suppression of astrocytic glycolysis by glutamate (Ruminot et al. 2011). Together, these findings suggest that transport of glucose analogues might not reflect the concurrent utilization of glucose in brain cells. Yet, 6-NBDG has been used to examine glucose metabolism of neuronal and astrocytic perikarya in barrel cortex of anesthetized rats (Chuquet et al. 2010). An increased astrocytic but not neuronal accumulation of the fluorescent sugar was observed during whisker stimulation, and was interpreted as a proof of preferential glucose uptake and metabolism by astrocytes upon stimulation (Chuquet et al. 2010). More recently, the same outcomes were reported in hippocampal and cerebellar tissue slices (Jakoby et al. 2012). An interesting feature of this study is that measurements of glucose uptake using either FRET based nanosensor or 6-NBDG were found to be anticorrelated in cultured neurons and astrocytes. In particular, the faster the uptake of glucose the slower the uptake of 6-NBDG. It remains to be established if this effect is as an indication of the uptake capacity of 6-NBDG in different cell types due to specific GLUT isoforms, which was the authors interpretation (Jakoby et al. 2012), or whether it underlies an intrinsic relation between uptake of the two sugars independently of the particular GLUT isoform mediating the transport. The experiments performed by Jakoby and coworkers on tissue slices and cell cultures confirm the previous observations that NBDG derivatives are preferentially taken up by glial cells.

The aim of the present work is to provide a theoretical framework to understand the results of in vitro and in vivo experiments conducted with 6-NBDG. First, the relationship between glucose and 6-NBDG transport kinetics is examined theoretically by calculating the analytical expression for flow rate changes of two substrates (i.e. glucose and 6-NBDG). Then a simple case of 6-NBDG uptake by a cellular compartment is numerically solved for varying rate of glucose utilization. Different scenarios of microscopic parameters of the carrier proteins are finally considered to resemble the behaviour of GLUT1 transporter.

Methods

The present analysis takes advantage from the previously developed formalization of the four-state alternating-carrier model for glucose transporter (GLUT) proteins in the presence of two substrates (Deves & Krupka 1979b, Deves & Krupka 1979a) (Figure 1A). In particular, the substrate affinities for the cis and trans side of the membrane are assumed to be the same (i.e. symmetric model) in order to avoid any possible violation of thermodynamic constraints (Naftalin 2010, Naftalin 2008).

Figure 1. The four-state carrier model in the presence of two different substrates.

The definition of rate constants of glucose and 6-NBDG at the inside and outside faces of the GLUT is illustrated in left panel. Here solid lines denote binding/unbinding of the carrier to/from the ligand, whereas dashed lines denote reorientation of the carrier when it is either free or bound to the ligand. Glucose and 6-NBDG are represented by different symbols. As mentioned in the ‘Methods’ section, the symmetric model is here used, implying that the rates for forward and reverse reactions (reorientation and binding) are identical. The “o” and “i” subscripts refer to the outward- and inward-facing carrier, respectively. The microscopic parameters distinguish the transitions between different carrier states and are related to the kinetic constants for transport of glucose and 6-NBDG (Table 1). Specifically, the set of parameter values can uphold different operational regimes for the carrier, namely a slow free-carrier reorientation regime (middle panel) or a slow ligand-carrier binding regime (right panel). Note that the arrows in panels B and C portray only a partial and simplified schematic representation of net glucose and 6-NBDG fluxes pertaining to the two different regimes of the carrier. In particular, dark arrows indicates the preferential direction of net conformational change. The rate of free-carrier reorientation versus ligand-carrier binding is critical since the effect of increased glucose metabolism by HK is to remove intracellular glucose and thus up-regulate the transition from carrier state CiGLCi to state Ci. Thus, the velocity of the subsequent transition identifies the actual operational regime of the carrier.

In order to avoid any confouding factor in the interpretation of simulations, we adopted a minimal metabolic model, which takes into account the concentration of intracellular (inside, “i” subscript) and extracellular (outside, “o” subscript) glucose and 6-NBDG (in equations termed NBDG to simplify notation) concentrations, can be written as:

where it is assumed that glucose and 6-NBDG are continuously delivered into the extracellular space from the bloodstream thus resulting in a constant extracellular concentration of these two metabolites (i.e. concentration-clamp). The constancy of extracellular concentration of glucose and 6-NBDG does not alter the main conclusions of the analysis. It is noted that glucose but not 6-NBDG is phosphorylated by HK, which is assumed to be always saturated by its substrate.

The general rate equations for inward fluxes of glucose and 6-NBDG are (see Table 1 for the definition of the various parameters in terms of individual rate constants of the carrier model):

where the denominator

is identical for the two rate equations. Combining the equations for JGLC and JNBDG by eliminating the term (GLCoNBDGi − GLCiNBDGo) gives:

Table 1.

Mathematical relationships between kinetic and microscopic carrier parameters.

| Description | Expression1 | |

|---|---|---|

| Equilibrium constants for substrate-carrier complex formation | KGLCo = k−1 / k1 | |

| KGLCi = k−2 / k2 | ||

| KNBDGo = k−3 / k3 | ||

| KNBDGi = k−4 / k4 | ||

| Half-saturation constant for zero trans entry of glucose | ||

| Half-saturation constant for zero trans entry of NBDG | ||

| Half-saturation constant for zero trans exit of glucose | ||

| Half-saturation constant for zero trans exit of NBDG | ||

| Maximum rate of zero trans exit of glucose | ||

| Maximum rate of zero trans exit of NBDG | ||

| Constant for infinite trans entry of glucose | ||

| Constant for infinite trans entry of NBDG | ||

| Constant for infinite trans entry of glucose |

|

|

| Constant for infinite trans entry of NBDG | ||

| Maximum rate of infinite trans exit of glucose | ||

| Maximum rate of infinite trans exit of NBDG |

For the derivation of these expressions, see (Deves & Krupka 1979a) and references therein. The microscopic parameters connote the conformational changes of the carrier shown in Figure 1.

The symbol Ct represents the concentration of the carrier in all forms, and therefore the tissue concentration.

The time derivative of this relation can be calculated as:

Note that, although the consumption of glucose does not appear explicitly here, it is actually contained into the glucose gradient, which can be expressed as:

Previous studies on GLUT kinetics showed that the free-carrier reorientates much more slowly relative to the ligand-carrier complex (Carruthers 1990, Deves & Krupka 1979a, Barros et al. 2009, Whitesell et al. 1989). This behavior implies the following conditions:

Normally the flux of NBDG is about 2000- to 3000-fold lower than that of glucose (Speizer et al. 1985, Cloherty et al. 1995), therefore V̅GLCi ≫ V̅NBDGi, which is equivalent to have the single condition:

The latter inequality holds for very slow reorientation of the free-carrier compared to the ligand-carrier complex.

When this argument is taken into account, the equation of the flux derivative simplifies to:

which identifies a condition where flux variations of glucose are accompanied by contrary flux variations of NBDG. This condition reflects a partial operational regime of the so-called counterflow or obligatory exchange. Strictly, counterflow is the uphill flow of labeled ligand driven by the downhill flow of unlabeled ligand, which applies to situations in which there is no substrate on one side. Obligatory exchange occurs when reorientation of the free-carrier is prohibited. It is important to note that these conclusions are model-independent, as the underlying kinetics does not require the mobile-carrier model and is also explainable using the two fixed site model (for demonstration, see Carruthers 1990, Naftalin 2010). Straightforwardly, the mobile-carrier explanation is that the path for ligand exchange short-circuits the slow path of free-carrier transit. We will refer to this behavior of the carrier as slow free-carrier reorientation regime (Figure 1B).

On the other hand, fluxes of glucose and 6-NBDG can also change in the same direction if the above-mentioned inequality is reversed to:

This means that the term dJNBDG / dt is always positive. This condition implies that the rate of ligand-carrier binding is much lower than the rate of free carrier reorientation, and therefore the return of the carrier from the inward-facing to the outward-facing configuration is favored when it is not bound to the ligand. We will refer to this behavior of the carrier as slow ligand-carrier binding regime (Figure 1C). It is noted that the two different regimes here described are mutually exclusive, thus the slow free-carrier reorientation regime can also be defined as high ligand-carrier binding regime, and vice versa. Here we adopted the present terminology in order to pinpoint where the actual changes in parameter values were made, bearing in mind that these changes have to be interpreted in relative terms. The two different regimes can be intuitively appreciated in terms of net process (remember that all transitions of the carrier are reversible) by considering that the rise in glucose metabolism (i.e. removal of intracellular glucose by HK activity) impacts on the carrier by “pulling” the transition from state CiGLCi to state Ci (Figure 1B,C). The latter state thus represents the main node point governing carrier behavior according to the relative velocity between reorientation of free-carrier (from Ci to Co) and binding of the carrier to the other available substrate (from Ci to CiNBDGi).

In order to examine whether brain GLUT1 isoform satisfies the above theoretical predictions, the model is here applied to a cellular compartment with varying rates of glucose phosphorylation by HK. In particular, to simulate departures from steady-state conditions the HK activity was either up- or down-regulated by 50% relative to its basal reaction rate. The core model uses the carrier parameters estimated at the blood-brain barrier (Barros et al. 2009). Notably, the glucose gradient between blood and parenchyma is much higher compared to the glucose gradient between extracellular and intracellular space within the tissue (Simpson et al. 2007). Furthermore, astrocytes express different GLUT isoform (predominance of 45 kDa-GLUT-1 isoform) compared with endothelial cells (55 kDa-GLUT-1 isoform) (Simpson et al. 2007). Therefore, it is likely that the microscopic parameters of astrocytic GLUT1 isoform are slightly dissimilar from those relative to blood-brain barrier GLUT1 isoform. However, we conformed to the parameter set used in previous kinetic analysis, where astrocytic and endothelial GLUT1 are assumed to be kinetically similar (Barros et al. 2009).

Model simulations were carried out by numerical integration using the software MATLAB (The Mathworks Inc., Natick MA, USA; http://www.mathworks.com/) version 7.0.4 R14.

Results

Simulations performed using available microscopic carrier parameters (i.e. core model) show that cellular uptake of 6-NBDG decreases when glucose phosphorylation is actually stimulated (Figure 2). This indicates that a relatively low rate of free-carrier reorientation compared with the velocity of ligand binding (200 s−1 versus 3000 s−1, see column 1 in Table 2) is already sufficient to obtain opposite flux variations of glucose and NBDG. The slow reorientation of the vacant carrier is not the sole determinant in the glucose/NBDG exchange underlying this particular regime of the transporter. Indeed, a key role is played by the nearly 300-fold higher dissociation constants of glucose (40 mM) relative to that of 6-NBDG (0.13 mM), which favors rapid glucose dissociation and NBDG association from and to the carrier, respectively, and thus the counterflow-like behavior.

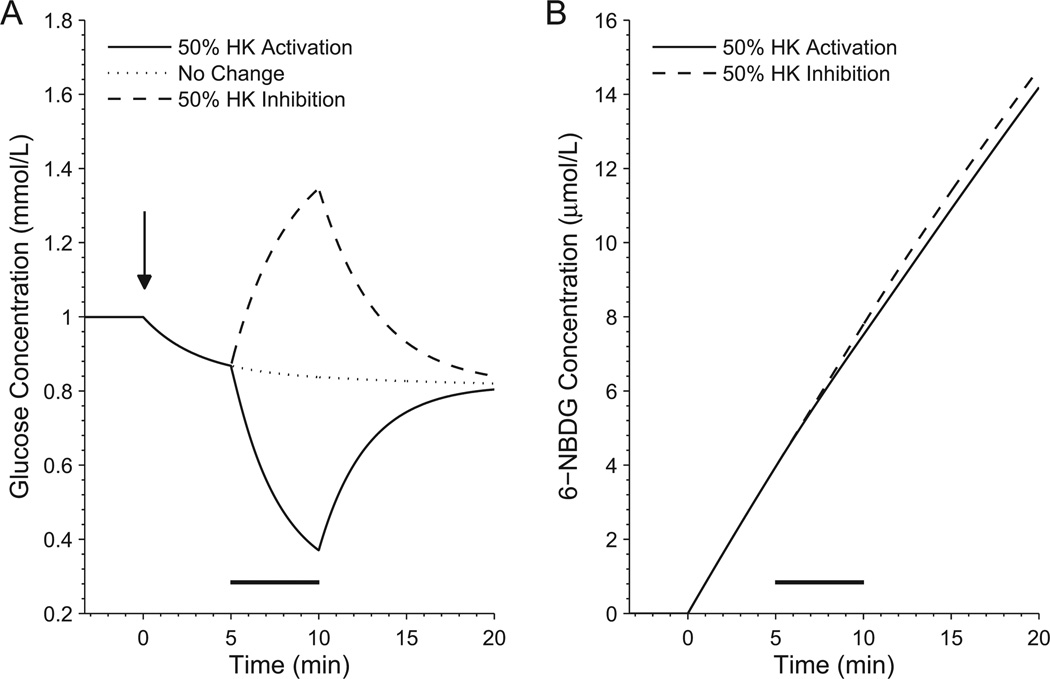

Figure 2. Simulated time course of intracellular glucose and 6-NBDG concentration during changes in glucose metabolism (slow free-carrier reorientation regime - core model).

Due to the competitive inhibition of glucose uptake by 6-NBDG, the glucose concentration decreases as soon as 6-NBDG is infused at time zero (arrow, left panel). Both the extent of the glucose transport inhibition and the amount of 6-NBDG accumulated intracellularly over time depend on the added 6-NBDG concentration, which however is not a critical parameter for the conclusions of the present analysis. Increases in substrate flow through HK (black horizontal bar), i.e. increases in the rate of glucose phosphorylation, are accompanied by decreases in intracellular glucose level and increased glucose uptake. Since the carrier works in counterflow-like conditions, a decrease in cellular 6-NBDG uptake rate is observed when HK is activated (right panel). This observation implies that augmented metabolic rate actually slows down the uptake of 6-NBDG. The converse is also true, i.e. inhibition of hexokinase and subsequent increase in intracellular glucose level and decrease in glucose uptake brings about a rise in 6-NBDG influx. Note that the changes in intracellular glucose level occur on top of the decrease due to transport inhibition by 6-NBDG relative to basal conditions (left panel, dotted line). In the simulations shown in the present figure, HK velocity is increased or decreased by 50% relative to its basal reaction rate (onset at 5 minutes, duration 5 minutes). Parameter values for this figure are listed in column 1 of Table 2, and are relative to the core model conditions.

Table 2.

Parameters values used in model simulations.

| Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Units | low free-carrier reorientation regime | low ligand-carrier binding regime | ||

|

Figure 2 (core model) |

Figure 4A | Figure 3 | Figure 4B | ||

| f1 = f−1 | s−1 | 200 | 20 | 200 | 200 |

| f2 = f−2 | s−1 | 3000 | 3000 | 3000 | 3000 |

| f3 = f−3 | s−1 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| KD(GLC) = k−1/k1 = k−2/k2 | mM | 40 | 40 | 2 | 0.33 |

| k1 = k2 | s−1 | 3000 | 3000 | 0.00037 | 0.0002 |

| k−1 = k−2 | mM s−1 | 120000 | 120000 | 0.00074 | 0.000066 |

| KD(NBDG) = k−3/k3 = k−4/k4 | mM | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| k3 = k4 | s−1 | 3000 | 3000 | 0.0000077 | 0.0000077 |

| k−3 = k−4 | Mm s−1 | 390 | 390 | 0.000001 | 0.000001 |

| Ct | µM | 0.278 | 1.052 | 116.76 | 283.56 |

| JHK | µM s−1 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 |

| GLCo | mM | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| NBDGo | µM | 100 | 25 | 100 | 100 |

The sets of parameters are chosen to obtain a given percent difference of intracellular 6-NBDG accumulation between conditions of 50% stimulated and 50% inhibited cell glucose metabolism. In particular, this difference is ~1% for Figure 2 and Figure 3, whereas it is ~12% for Figure 4A,B. Note that Figure 2 and Figure 4A identify the slow free-carrier reorientation regime, and Figure 3 and Figure 4B identify the slow ligand-carrier binding regime. Changes of parameter values from core model simulation (Figure 2) are emphasized in boldface.

All values are taken from Barros et al (2009), except for k±1, k±2, k±3, k±4 that are known as ratios (i.e. KD(GLC) and KD(NBDG). See Barros et al (2009) for references about the experimental determination of these constants. Note the large decrease of the dissociation constant for glucose within the low ligand-carrier binding regime (from 40 mM to 2 mM to 0.33 mM), whereby the corresponding dissociation constant for NBDG remains unaltered (0.13 mM).

The concentration of GLUTs in brain cells (here represented by the parameter Ct) is estimated to be in the order of fractions of µM (~0.4 pmol/mg total protein assuming about 0.9 g/100mL of total protein content in cerebral cortex) (see Table 1 in Simpson et al. 2007). Although there is uncertainty on these numbers, the total concentration of the carrier is possibly smaller than that used in core model. However, decreasing Ct from the value of core model simulations requires a corresponding increase of f±2 relative to f±1 (see Table 1) in order to maintain physiological basal and stimulation-induced glucose level (simulations not shown). In turn, increase in f±2 will result in reduced f±1/f±2 ratio, thus further confirming the conditions of slow free-carrier reorientation for GLUTs. On the other hand, the condition of slow ligand-carrier binding requires a too high tissue concentration of the transporter.

For the kinetic significance of the various parameters, see Figure 1.

An accumulation of 6-NBDG inside the cell in presence of increased glucose metabolism can also be simulated (Figure 3), but in this case it is necessary to reduce the dissociation constant for glucose (KD(GLC)), see column 3 in Table 2) by a factor of 20 and concomitantly assume very small rates of glucose and 6-NBDG binding. Essentially, this particular regime of the carrier identifies a situation in which the transporter returns preferentially empty from the intracellular to the extracellular side of the membrane, and translocates either glucose or 6-NBDG with a similar probability due to the similarity of binding rates and dissociation constants. Importantly, the assumption that sugar binding is much slower than free carrier reorientation is not supported by current literature (Carruthers 1990, Naftalin 2010).

Figure 3. Simulated time course of intracellular glucose and 6-NBDG concentration during changes in glucose metabolism (slow ligand-carrier binding regime).

In these conditions (20-fold reduction in glucose dissociation constant KD(GLC)) the up-regulation of glucose metabolism (black horizontal bar) is paralleled by a stimulation of 6-NBDG uptake (right panel). In kinetic terms this is equivalent to assuming that return of the carrier from the cytosolic side of the membrane to the cell exterior is faster when the transporter is vacant, thus no compounds are counter transported. Glucose transients (left panel) are nearly indistinguishable from those showed in Figure 3. Infusion of 6-NBDG started at time zero (arrow, left panel). Note that the changes in intracellular glucose level occur on top of the decrease due to transport inhibition by 6-NBDG relative to basal conditions (left panel, dotted line). In the simulations shown in the present figure, HK velocity is increased or decreased by 50% relative to its basal reaction rate (onset at 5 minutes, duration 5 minutes). Parameter values for this figure are listed in column 3 of Table 2.

Thus, we found that the relation between 6-NBDG and concomitant glucose uptake depends on the dissociation constants of the two sugars as well as on the slowest step in the configurational changes of the carrier, whether the reorientation of the free carrier or the binding of the ligand to the carrier. Notably, using the currently available parameters the model supports the former situation (i.e. the parameter values satisfy the slow free-carrier reorientation regime described in the ‘Methods’ section).

The simulated departures from steady-state 6-NBDG influx upon changes in metabolic demand are very small (few percent). However, a recent experiment on 6-NBDG uptake by neurons and astrocytes (Chuquet et al. 2010) showed a ~10% difference of fluorescence intensity between the two cell types after the stimulation. Therefore, we examined to what extent either the slow free-carrier reorientation regime (i.e. core model) or the slow ligand-carrier binding regime should be upset to produce the experimentally observed difference in NBDG uptake. We thus performed additional simulations by exacerbating the different regimes (see columns 2 and 4 in Table 2). We indeed found a substantial (5–6%) departure of 6-NBDG transport patterns between basal and stimulated conditions using a 10-fold lower rate of free-carrier reorientation (see Figure 4A). Remarkably, a difference of this magnitude could be obtained in the slow ligand-carrier binding regime (Figure 4B) only reducing the dissociation constant for glucose to unreasonably low value (Table 2, column 4). This means that, without invoking further assumptions, the agreement with experimental data is obtained with more conservative changes within the counterflow-like behavior of the transporter.

Figure 4. Intracellular accumulation of 6-NBDG during increase in glucose metabolism for low rates of either free carrier reorientation or ligand-carrier binding.

Depending on carrier parameters, the up-regulation of glucose metabolism (black horizontal bar) brings about a decrease or an increase in 6-NBDG concentration relative to conditions of unchanged or down-regulated glucose utilization. Flux of 6-NBDG varies in opposite directions whether the carrier operates in slow free-carrier reorientation regime (left panel, 10-fold reduction in f1 = f−1) or slow ligand-carrier binding regime (right panel, >120-fold reduction in glucose dissociation constant KD(GLC)). It is noted that the flux of 6-NBDG is always positive (i.e. intracellular 6-NBDG always rises) due to the positive concentration gradient of 6-NBDG between extra- and intracellular space. At 10 minutes after end of stimulation the intracellular concentration of glucose has almost returned to its basal level (which is nearly 0.85 mmol/L due to inhibition of transport by NBDG). Determination of 6-NBDG accumulation at this time gives a change of 5–6% below or above its value in absence of metabolic challenge (insets). This would mean that the difference in NBDG content in two different compartments behaving in opposite direction with respect to glucose metabolism would be in the order of 10–12%. Parameter values for this figure are listed in columns 2 and 4 of Table 2.

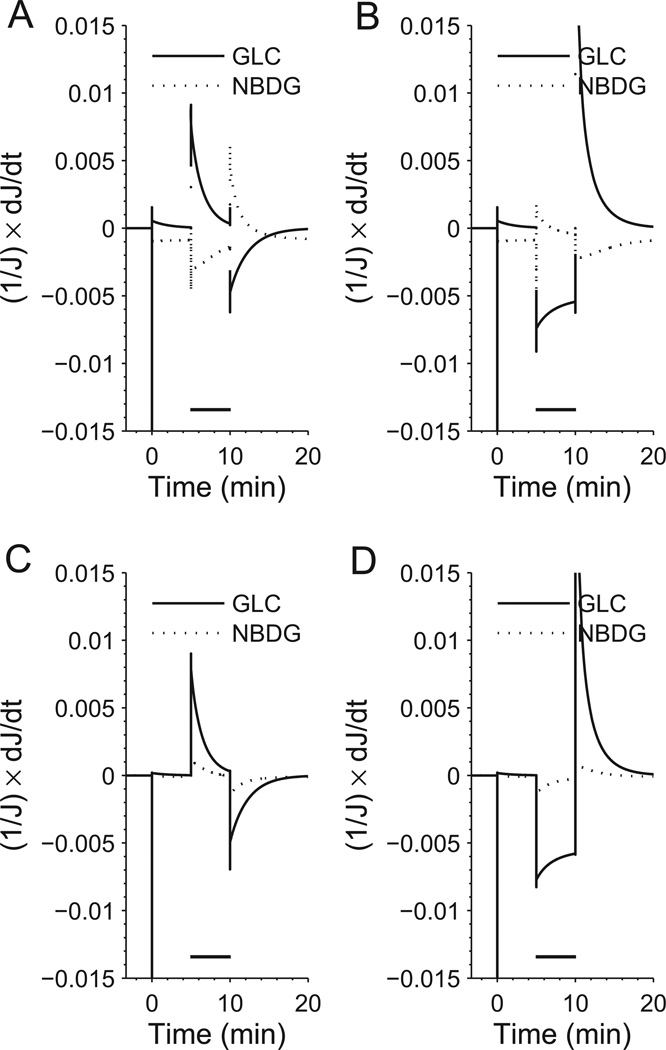

To confirm that the simulated kinetics of glucose and 6-NBDG transport is consistent with the theoretical model described above (see ‘Methods’ section), we plotted the time derivative of the glucose and 6-NBDG flow rates as a function of time (Figure 5). In agreement with the theory, we found that for the slow free-carrier reorientation regime the two fluxes always changes in opposite direction, i.e. their time derivative have different sign, both during HK activation (Figure 5A) and inhibition (Figure 5B). Conversely, for the slow ligand-carrier binding regime the changes of the two fluxes (Figure 5C,D) takes place in the same direction, i.e. their time derivatives have the same sign. These results emphasize the mutually exclusive character of the different carrier regimes and show that the the time derivatives of glucose and 6-NBDG fluxes are either always correlated or always anti-correlated.

Figure 5. Time derivatives of glucose and 6-NBDG transport flow rates as a function of time.

The time derivative of fluxes of glucose and 6-NBDG have different sign when the carrier behaves in the slow free-carrier reorientation regime. This means that the fluxes vary in opposite directions, which is true both during HK activation (top left panel) and inhibition (top right panel). When the carrier is in the slow ligand-carrier binding regime, the situation is reversed and the time derivatives of glucose and 6-NBDG fluxes share the same sign. This means that the fluxes vary in the same direction in condition of both HK activation (bottom left panel) and inhibition (bottom right panel).

Discussion

During enhanced energy demand many cell types including cerebral neurons and astrocytes up-regulate oxidative metabolism and hence substrate flow through the glycolytic pathways, which is accomplished by processing of glucose first by HK and enzymes of the glycolytic chain. In particular, the intracellular concentration of the sugar transiently decreases during conditions of increased phosphorylation of glucose. This creates a concentration gradient that in turn results in augmented flux of glucose inside the cell. As 6-NBDG cannot be metabolized, there is not a corresponding change in the concentration difference of the glucose analogue between intra- and extracellular space. Thus, uptake of glucose is actively driven by changes in metabolism, whereas that of 6-NBDG is not. It is important to remark that similar considerations might apply to the poorly metabolizable 2-NBDG derivative. However, a quantitative estimate of the effect of glucose metabolism on 2-NBDG transport requires the knowledge of the rate of 2-NBDG phosphorylation to 2-NBDG 6-phosphate as well as the rate of degradation of 2-NBDG. In particular, if phosphorylation rate of 2-NBDG is slower than its transport, the exchange between glucose and unmetabolized 2-NBDG could still produce the effect reported here for 6-NBDG, which can be further intensified by the rapid degradation of 2-NBDG to non-fluorescent products (Yoshioka et al. 1996). It should be also mentioned that retention of intracellular 2-NBDG can be overestimated due to incorporation into glycogen (Louzao et al. 2008), which is especially relevant for glycogen-rich astrocytes. Overall, it seems that the effects of changes in glucose supply and demand on NBDG resemble those on 3-O-methylglucose, although with different kinetics. Specifically, using different modeling procedures to fit experimental data (see ‘Introduction’ section) a lot of work in the past decades (Buschiazzo et al. 1970, Gjedde & Diemer 1983, Dienel et al. 1991) have arrived to conclusions similar to those we report in the present study (Nakanishi et al. 1996).

Recently, it was reported that 6-NBDG accumulation significantly increases in astrocytes and slightly decreases in neurons after brain stimulation in vivo (Chuquet et al. 2010) and in vitro (Jakoby et al. 2012). With the current knowledge, the observed difference in 6-NBDG uptake surely indicates that glucose utilization is unevenly enhanced in the two cell types, provided that transport of the sugar is largely independent of the specific cellular GLUT isoforms. Yet, the results were interpreted as proof of increased uptake of extracellular glucose by astrocytes relative to neurons. Our modeling outcomes suggest that the increased flow of 6-NBDG in astrocytes actually reflects down-regulation of glucose phosphorylation. The present kinetic analysis supports the latter interpretation under the commonly accepted assumption that the rate of reorientation of the free-carrier is sufficiently slower than binding of the carrier with ligand and reorientation of the ligand-carrier complex (Figure 1). The magnitude of 6-NBDG uptake departure from steady-state condition observed experimentally during metabolic challenge (Chuquet et al. 2010) could be more easily (i.e. by adopting conservative changes in parameter values) reproduced in our simulations when the transporter operates in the slow free-carrier reorientation regime but not when it operates in the slow ligand-carrier binding regime. Thus, our results are in agreement with the notion that variations in 6-NBDG concentration follow those of glucose and hence the opposite of glucose utilization (Dienel 2012). Unfortunately, due to the lack of detailed information about neuronal GLUT3 isoform we were unable to directly examine the fate of 6-NBDG in individual compartments under different scenarios. However, assuming GLUT3 to be kinetically similar to GLUT1 would give a >10% difference in 6-NBDG accumulation between two adjacent compartments where, for instance, glucose uptake is oppositely modulated by the stimulation (see Figure 4).

We have recently proposed that glycogenolysis in astrocytes after brain activation might increase intracellular glucose-6-phosphate level thereby suppressing astrocytic glucose phosphorylation by hexokinase via product-inhibition (DiNuzzo et al. 2010, DiNuzzo et al. 2011, DiNuzzo et al. 2012). Interestingly enough, this hypothesis is consistent with a reduction of astrocytic glucose metabolism and a resulting increase of both glucose and 6-NBDG in astrocytes, the latter reported by the above-mentioned studies (Chuquet et al. 2010, Jakoby et al. 2012). We have previously showed by metabolic modeling that the concentration of astrocytic glucose due to inhibition of hexokinase might transiently surpass the concentration of interstitial glucose favoring the gradient-driven efflux of the sugar by astrocytes (DiNuzzo et al. 2010). According to the present analysis, the astrocytic release of glucose would further enhance the influx of 6-NBDG in these cells.

In conclusion, we found that the transport of 6-NBDG does or does not parallel the concurrent transport of glucose depending on the microscopic parameters of the carrier proteins. Specifically, using the available parameter values relative to the cerebral GLUT1 isoform the model predicts that the transporter behaves in the slow free-carrier reorientation regime. Therefore, the flow changes of 6-NBDG and glucose through the carrier always take place in opposite directions. While the exact relation between glucose and 6-NBDG transport by neuronal and astrocytic GLUT isoforms needs a detailed knowledge of reorientation rates of free- and ligand-bound carrier, it is suggested that the utilization of intracellular 6-NBDG accumulation as a surrogate of glucose uptake and metabolism in cells preferentially expressing GLUT1 isoform (e.g., astrocytes) should await further research. Unambiguous interpretation of intracellular 6-NBDG accumulation mediated by GLUT carrier proteins requires detailed study of transport kinetics of glucose and NBDG. In the meantime, it is worthwhile to issue a word of caution regarding the interpretation of data obtained with glucose analogues, as the symmetric four-state GLUT model supports antiport not symport of glucose and NBDG.

Acknowledgments

S. M. thanks the support of the American Diabetes Association (grant number 07-07-DC2), along with the support of the National Center for Research Resources (Grant Number P41 RR008079) and the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (Grant Number P41 EB015894) of NIH. Additional funding supports to CMRR are: Minnesota Medical Foundation, P30 NS057091 and P30 NS076408. This work was finally supported by the NIH grant UL1RR033183 and KL2 RR033182 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) to the University of Minnesota Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI).

Abbreviations used

- 6-NBDG

6-(N-(7-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazol-4-yl)amino)-2-deoxyglucose

- GLC

glucose

- GLUT

glucose transporter

- HK

hexokinase

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aller CB, Ehmann S, Gilman-Sachs A, Snyder AK. Flow cytometric analysis of glucose transport by rat brain cells. Cytometry. 1997;27:262–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros LF, Bittner CX, Loaiza A, Ruminot I, Larenas V, Moldenhauer H, Oyarzun C, Alvarez M. Kinetic validation of 6-NBDG as a probe for the glucose transporter GLUT1 in astrocytes. J Neurochem. 2009;109(Suppl 1):94–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.05885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittner CX, Valdebenito R, Ruminot I, et al. Fast and reversible stimulation of astrocytic glycolysis by K+ and a delayed and persistent effect of glutamate. J Neurosci. 2011;31:4709–4713. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5311-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschiazzo PM, Terrell EB, Regen DM. Sugar transport across the blood-brain barrier. Am J Physiol. 1970;219:1505–1513. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.219.5.1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers A. Facilitated diffusion of glucose. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:1135–1176. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuquet J, Quilichini P, Nimchinsky EA, Buzsaki G. Predominant enhancement of glucose uptake in astrocytes versus neurons during activation of the somatosensory cortex. J Neurosci. 2010;30:15298–15303. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0762-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloherty EK, Sultzman LA, Zottola RJ, Carruthers A. Net sugar transport is a multistep process. Evidence for cytosolic sugar binding sites in erythrocytes. Biochemistry. 1995;34:15395–15406. doi: 10.1021/bi00047a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deves R, Krupka RM. A general kinetic analysis of transport. Tests of the carrier model based on predicted relations among experimental parameters. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979a;556:533–547. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(79)90139-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deves R, Krupka RM. A simple experimental approach to the determination of carrier transport parameters for unlabeled substrate analogs. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979b;556:524–532. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(79)90138-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienel GA. Fueling and imaging brain activation. ASN Neuro. 2012 doi: 10.1042/AN20120021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienel GA, Cruz NF, Mori K, Holden JE, Sokoloff L. Direct measurement of the lambda of the lumped constant of the deoxyglucose method in rat brain: determination of lambda and lumped constant from tissue glucose concentration or equilibrium brain/plasma distribution ratio for methylglucose. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1991;11:25–34. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1991.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitriadis G, Maratou E, Boutati E, Psarra K, Papasteriades C, Raptis SA. Evaluation of glucose transport and its regulation by insulin in human monocytes using flow cytometry. Cytometry. Part A : the journal of the International Society for Analytical Cytology. 2005;64:27–33. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNuzzo M, Mangia S, Maraviglia B, Giove F. Glycogenolysis in astrocytes supports blood-borne glucose channeling not glycogen-derived lactate shuttling to neurons: evidence from mathematical modeling. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1895–1904. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNuzzo M, Mangia S, Maraviglia B, Giove F. The Role of Astrocytic Glycogen in Supporting the Energetics of Neuronal Activity. Neurochem Res. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11064-012-0802-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNuzzo M, Maraviglia B, Giove F. Why does the brain (not) have glycogen? Bioessays. 2011;33:319–326. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gjedde A, Diemer NH. Autoradiographic determination of regional brain glucose content. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1983;3:303–310. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1983.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruetter R, Novotny EJ, Boulware SD, Rothman DL, Mason GF, Shulman GI, Shulman RG, Tamborlane WV. Direct measurement of brain glucose concentrations in humans by 13C NMR spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:1109–1112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.3.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Abe T, Takaoka R, Tanahashi N. Fluorometric determination of glucose utilization in neurons in vitro and in vivo. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:993–1003. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000127661.07591.DE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakoby P, Schmidt E, Ruminot I, Gutierrez R, Barros LF, Deitmer JW. Higher Transport and Metabolism of Glucose in Astrocytes Compared with Neurons: A Multiphoton Study of Hippocampal and Cerebellar Tissue Slices. Cereb Cortex. 2012 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhs309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung DW, Ha HH, Zheng X, Chang YT, Williams DR. Novel use of fluorescent glucose analogues to identify a new class of triazine-based insulin mimetics possessing useful secondary effects. Molecular bioSystems. 2011;7:346–358. doi: 10.1039/c0mb00089b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leira F, Louzao MC, Vieites JM, Botana LM, Vieytes MR. Fluorescent microplate cell assay to measure uptake and metabolism of glucose in normal human lung fibroblasts. Toxicology in vitro : an international journal published in association with BIBRA. 2002;16:267–273. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2333(02)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loaiza A, Porras OH, Barros LF. Glutamate triggers rapid glucose transport stimulation in astrocytes as evidenced by real-time confocal microscopy. J Neurosci. 2003;23:7337–7342. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-19-07337.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louzao MC, Espina B, Vieytes MR, Vega FV, Rubiolo JA, Baba O, Terashima T, Botana LM. "Fluorescent glycogen" formation with sensibility for in vivo and in vitro detection. Glycoconj J. 2008;25:503–510. doi: 10.1007/s10719-007-9075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangia S, DiNuzzo M, Giove F, Carruthers A, Simpson IA, Vannucci SJ. Response to 'comment on recent modeling studies of astrocyte-neuron metabolic interactions': much ado about nothing. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2011;31:1346–1353. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naftalin RJ. Alternating carrier models of asymmetric glucose transport violate the energy conservation laws. Biophys J. 2008;95:4300–4314. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.136366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naftalin RJ. Reassessment of models of facilitated transport and cotransport. The Journal of membrane biology. 2010;234:75–112. doi: 10.1007/s00232-010-9228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakanishi H, Cruz NF, Adachi K, Sokoloff L, Dienel GA. Influence of glucose supply and demand on determination of brain glucose content with labeled methylglucose. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:439–449. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199605000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porras OH, Loaiza A, Barros LF. Glutamate mediates acute glucose transport inhibition in hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24:9669–9673. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1882-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qutub AA, Hunt CA. Glucose transport to the brain: a systems model. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;49:595–617. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruminot I, Gutierrez R, Pena-Munzenmayer G, Anazco C, Sotelo-Hitschfeld T, Lerchundi R, Niemeyer MI, Shull GE, Barros LF. NBCe1 Mediates the Acute Stimulation of Astrocytic Glycolysis by Extracellular K+ J Neurosci. 2011;31:14264–14271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2310-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada M, Kawamoto S, Hirose Y, Nakanishi M, Watanabe H, Watanabe M. Regional differences in glucose transport in the mouse hippocampus. The Histochemical journal. 1994;26:207–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson IA, Carruthers A, Vannucci SJ. Supply and demand in cerebral energy metabolism: the role of nutrient transporters. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:1766–1791. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speizer L, Haugland R, Kutchai H. Asymmetric transport of a fluorescent glucose analogue by human erythrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;815:75–84. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(85)90476-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesell RR, Regen DM, Beth AH, Pelletier DK, Abumrad NA. Activation energy of the slowest step in the glucose carrier cycle: break at 23 degrees C and correlation with membrane lipid fluidity. Biochemistry. 1989;28:5618–5625. doi: 10.1021/bi00439a042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshioka K, Saito M, Oh KB, Nemoto Y, Matsuoka H, Natsume M, Abe H. Intracellular fate of 2-NBDG, a fluorescent probe for glucose uptake activity, in Escherichia coli cells. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1996;60:1899–1901. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou C, Wang Y, Shen Z. 2-NBDG as a fluorescent indicator for direct glucose uptake measurement. Journal of biochemical and biophysical methods. 2005;64:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jbbm.2005.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]