Abstract

Objective

YouTube is now the second most visited site on the Internet. We aimed to compare characteristics of and messages conveyed by cigarette- and hookah-related videos on YouTube.

Methods

Systematic search procedures yielded 66 cigarette-related and 61 hookah-related videos. After 3 trained qualitative researchers used an iterative approach to develop and refine definitions for the coding of variables, 2 of them independently coded each video for content including positive and negative associations with smoking and major content type.

Results

Median view counts were 606,884 for cigarettes and 102,307 for hookahs (P<.001). However, the number of comments per 1,000 views was significantly lower for cigarette-related videos than for hookah-related videos (1.6 vs 2.5, P=.003). There was no significant difference in the number of “like” designations per 100 reactions (91 vs. 87, P=.39). Cigarette-related videos were less likely than hookah-related videos to portray tobacco use in a positive light (24% vs. 92%, P<.001). In addition, cigarette-related videos were more likely to be of high production quality (42% vs. 5%, P<.001), to mention short-term consequences (50% vs. 18%, P<.001) and long-term consequences (44% vs. 2%, P<.001) of tobacco use, to contain explicit antismoking messages (39% vs. 0%, P<.001), and to provide specific information on how to quit tobacco use (21% vs. 0%, P<.001).

Conclusions

Although Internet user–generated videos related to cigarette smoking often acknowledge harmful consequences and provide explicit antismoking messages, hookah-related videos do not. It may be valuable for public health programs to correct common misconceptions regarding hookah use.

Keywords: waterpipe, hookah, cigarette, internet, user-generated content

INTRODUCTION

The use of a hookah to smoke tobacco is an emerging trend among teenagers and young adults in the United States.1-5 About one-third of college students and one-sixth of high school students have ever used a hookah to smoke tobacco,1-5 making it the second most common form of tobacco use by young people.3 Because as many as 50% of hookah users do not also smoke cigarettes, this form of tobacco use affects many individuals who may have otherwise never consumed nicotine products.3, 6

Hookah users are exposed to large amounts of toxins.7-11 In fact, the smoke from one hookah session may contain about 40 times the tar,7, 10 30 times the carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons,8 10 times the carbon monoxide, 7, 10 and 2 times the nicotine7, 10 of a single cigarette. Despite this, many believe that hookah use is less addictive, less harmful, more aesthetically appealing, and more socially acceptable than cigarette use.3, 5, 6, 12 This belief, combined with permissive policies regulating hookah tobacco, may be linked to the proliferation of hookah use.13

Recent analyses suggest that cigarette smoking imagery on YouTube and other social networking Web sites is widespread and unregulated.14-16 YouTube, an Internet-based forum for posting videos, is now the second most visited site on the Internet.17 As of May 2010, YouTube exceeded 2 billion views per day, with 24 hours of video uploaded per minute.18 Because YouTube videos can reach large numbers of viewers quickly, these videos are increasingly being used for corporate marketing.14, 15, 19 Public health researchers and practitioners have begun to recognize the importance of better understanding the content of YouTube exposures related to health, not only because of the popularity of these exposures but also because of the known associations between tobacco-related media messages and clinically relevant behaviors, such as initiation and maintenance of tobacco use.20-24

Freeman and Chapman began this line of research with their 2007 analysis of tobacco images and advertising on YouTube.25 They examined relevant cigarette-related videos for content themes and viewer feedback and discussed the possible involvement of the tobacco industry in this form of word-of-mouth marketing.25 In 2010, when Forsyth and Malone examined 124 of the most popular YouTube videos about cigarette use, they found that these videos mentioned specific brand names of cigarettes over 40% of the time, frequently associated cigarettes with magic tricks and sexual themes, and commonly portrayed cigarette smoking in a positive light.16 These results illuminated an important manner in which young people were receiving media exposure to smoking, and this helped public health researchers and practitioners frame new questions and interventions related to media messages about tobacco use.

To our knowledge, there has been no systematic analysis comparing videos of cigarette use and videos of hookah use. Given the recent popularity of hookah use and misconceptions about it, this type of analysis would be a valuable next step in developing interventions. With this in mind, we designed and performed a qualitative study to compare the content of YouTube videos related to cigarette use with those related to hookah use.

METHODS

Study Design

We selected a qualitative approach because we believed it would allow us to gain a more in-depth understanding of the messages communicated by the videos than would a quantitative approach using simple checklists. We also believed that a more open-ended approach was preferable because little work has been done to date concerning analysis of YouTube videos.16

Video Search

On January 28, 2011, we conducted an initial search of English language videos on YouTube. Following the methodology of Forsyth and Malone,16 we searched for the terms cigarettes and smoking cigarettes. Similarly, we searched for the terms hookah and smoking hookah. We limited our study to these 4 terms because our search for similar terms—such as water pipe and narghile, which are used internationally by researchers and public health practitioners but are generally not used colloquially in English language videos on YouTube—did not yield further videos about tobacco use that met our selection criteria.

There are 2 different methods of prioritizing searches on YouTube: by view count (preferentially selecting videos that are the most commonly viewed) and by relevance (preferentially selecting videos that most exactly match a search term). We searched for the 4 terms by each of these 2 methods and collected the first 2 pages (20 “hits”) of results for each search. Selection of the first 20 hits is supported in the public health and information science literature.26-28 The selection processes yielded 80 videos for cigarette smoking and 80 for hookah smoking.

On March 28, 2011, we used the same methods to capture a second sample of 160 videos, for a total of 320 videos. There is precedent for sampling twice in 2-month increments, because it helps broaden the pool of possible videos.16

To obtain the final sample, we eliminated duplicate videos, defined as those in which more than half of the content or footage was identical, as occurs, for example, when someone copies previously posted material and adds a negligible amount of new material. We also eliminated irrelevant videos, defined as those in which there was no audio or visual reference to tobacco consumption via cigarettes or hookahs. Videos that dealt solely with marijuana cigarettes or e-cigarettes and did not mention traditional cigarettes or hookah were excluded. When videos contained both e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes, our coding reflected how traditional cigarettes were portrayed.

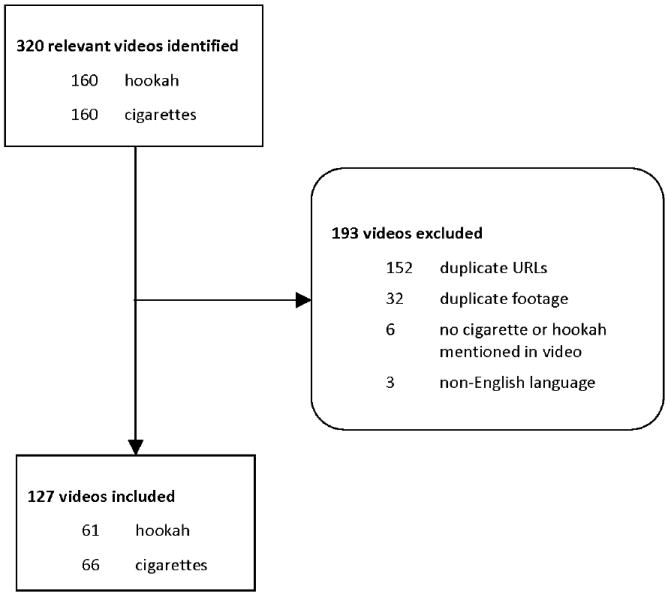

The final sample consisted of 127 videos, with cigarette- and hookah-related videos being almost equal. This occurred naturally, as there were similar numbers of videos for both categories that did not meet inclusion criteria. To ensure integrity of the data and facilitate analysis, we saved each video on the day of the search as a digital video file. We also prepared written transcripts of the audio portion of the videos.

Codebook Development

Two researchers with training in qualitative methods developed a preliminary codebook (manual) based on a grounded theory approach adapted for medical qualitative research by Crabtree and Miller.29, 30 Using in vivo coding and focusing on the audio and visual images provided, the researchers assessed 20% of the sample of videos. After independently finding emerging key themes, they discussed the themes with each other and combined similar coding for themes. Together with a third researcher, they recoded a subsequent set of videos and then met again to address further questions and refinements of coding.

After the 3 researchers clarified the definition of each code, they developed a final codebook that outlined specific inclusion and exclusion criteria for each code and included examples of imagery that met these criteria. Then 2 trained coders worked independently to review and code each of the 127 videos in its entirety. For the variables coded, statistical analysis showed that interrater reliability, expressed in terms of Cohen’s κ, ranged from 0.82 to 1.00 (P<.001 for each code). In the rare cases of disagreement, the coders and other research team members worked together to achieve consensus.

Data Collection and Coding

General Characteristics of the Sample

For each video, we recorded the title, date of posting on YouTube, user name of the poster, length of the video in minutes and seconds, number of times the video was viewed on YouTube, number of comments from viewers, and number of times viewers recorded “like” or “dislike” after seeing the video. We also recorded the gender (male vs. female or mixed), approximate age (≤30 vs. >30 years), and race (white vs. nonwhite) of the video’s primary actor or narrator if this information was discernible.

Production Quality

We noted the production quality of each video and categorized it as follows: low if it was homemade and paid little or no attention to production values such as lighting, camera angles, sound quality, and titles; moderate if it was homemade but paid at least some attention to production values; or high if it was produced with considerable attention to these production values. We coded this variable because production factors may influence a viewer’s interpretation of and response to a video; for example, a viewer may be more likely to believe a message featuring high production values.31, 32

Video Portrayal of Smoking

We coded the overall portrayal of smoking as positive if the smoking was largely portrayed as attractive, fun, powerful, pleasurable, relaxing, or sexy. We coded it as negative if it was largely portrayed as undesirable, unattractive, or harmful. And we coded it as neutral if smoking was not portrayed in either a highly positive or highly negative light or there were contradictory or unclear messages about smoking.

We coded for numerous dichotomous variables. First, we coded for whether the depiction of smoking in the video was associated with specific characteristics that are often considered desirable, including humor, attractiveness, power, sexuality, sociability, and exoticness. Second, we coded for whether tobacco use in the videos was associated with short- or long-term health consequences, whether the video depicted smoking by children, and whether the video contained a specific antismoking message or included information about how to quit smoking. Third, we coded for whether a video did the following: claimed that particular products, such as electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), could minimize potential harm related to smoking; served as a product review; showed tricks involving smoking; provided information about how to smoke or how to set up a smoking device; encouraged smoking fetishism (capnolagnia, or sexual fantasies based on the sight of a person smoking); included music; served as a music video; included historical or documentary footage; or included poetry.

Analysis

To assess the frequencies of codes, we used quasi-statistical qualitative methodology29, 30 that involved summing the number of counts for each code and computing the proportion of all sites that contained the code. For continuous variables in non-normal distributions (such as view counts and rate of commentary), we used non-parametric 2-tailed Mann-Whitney U tests to compare sample medians. To compare the frequency for codes in cigarette-related videos with those in hookah-related videos, we used chi-square tests with an alpha of 0.05.

The complete research team then met again to explore examples of each code and probe for deeper meanings. Our synthesis of the findings and selection of exemplary quotations was guided by the principles of thematic synthesis, in which codes are organized into descriptive and then analytic themes.33 We selected this approach because it allows for in-depth and open-ended consideration of the themes and their relevance to public health and the ultimate need for intervention.

RESULTS

General Characteristics of the Sample

Of the sample of 127 videos, 66 (52%) were related to cigarette smoking and 61 (48%) were related to hookah smoking (Figure 1). Median video length was 150 seconds for cigarettes and 92 seconds for hookahs (Table 1). Median view counts were 606,884 for cigarettes and 102,307 for hookahs (P<.001). However, the number of comments per 1,000 views was significantly lower for cigarette-related videos than for hookah-related videos (1.6 vs. 2.5, P=.003). There was no significant difference in the number of “like” designations per 100 reactions (91 vs. 87, P=.39).

FIGURE 1.

Flow Chart Demonstrating Reasons for Exclusion

Table 1.

General Information of the Sample of 66 Cigarette-Related Videos and 61 Hookah-Related Videos

| General information | Cigarette-Related Videos | Hookah-Related Videos | P* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Length of video in seconds | 150 (83, 224) | 92 (62, 325) | .47 |

| Number of views | 606,884 (63,726; 1,408,240) | 102,307 (48,452; 255,222) | <.001 |

| Number of comments per 1,000 views | 1.6 (0.6, 3.2) | 2.5 (1.4, 3.6) | .003 |

| Number of “like” designations per 100 reactions† | 91 (73, 96) | 87 (73, 93) | .39 |

The Mann-Whitney U non-parametric rank sum significance test was used.

Reactions in this context include “like” and “dislike.” Thus, the median cigarette-related video had 91 “like” for every 9 “dislike” designations, while the median hookah-related video had 87 “like” for every 13 “dislike” designations.

Narrators and Production Quality

In both types of videos, the narrators or main characters were most commonly male, 30 years or younger, and white (Table 2). High production quality was more frequently found in cigarette-related videos compared with hookah-related videos (42% vs. 5%, P<.001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of the Sample of 66 Cigarette-Related Videos and 61 Hookah-Related Videos

| Characteristic | Cigarette-Related Videos | Hookah-Related Videos | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narrator characteristics | No. (%) | Example | No. (%) | Example | |

| Gender* | .22 | ||||

| Male | 42 (69) | N/A | 48 (79) | N/A | |

| Female or Mixed | 19 (31) | N/A | 13 (21) | N/A | |

| Age* | .02 | ||||

| ≤30 | 55 (85) | N/A | 59 (97) | N/A | |

| >30 | 10 (15) | N/A | 2 (3) | N/A | |

| Race* | .74 | ||||

| White | 41 (69) | N/A | 40 (67) | N/A | |

| Non-White | 18 (31) | N/A | 20 (33) | N/A | |

| Production quality | <.001 | ||||

| Low | 27 (41) | A homemade video, most likely recorded on a computer recording program, shows a college-aged white woman sitting in a bedroom and singing an acoustic version of a pop song that refers to cigarettes while a college-aged white man accompanies her on guitar. | 46 (75) | A blurry video, most likely produced on a cell phone, shows 2 South Asian men blowing large clouds of smoke and doing tricks with smoke after inhaling from a hookah pipe. | |

| Moderate | 11 (17) | In a homemade video that includes titles, music, edits, and some attention to lighting, an African American man in his mid-20s gives his opinion of the video of an Indonesian baby smoking cigarettes. | 12 (20) | In a homemade video of a hookah being prepared by several college-aged men, there are many special effects (e.g., editing cuts and fade-ins) as the text at the bottom of the screen explains the process and electronic dance music plays. | |

| High | 28 (42) | A professionally made music video that mentions cigarettes makes use of multiple camera angles in shots of a singer and dancers. It contains frequent editing cuts, clear audio, good lighting, and special effects such as slow motion. | 3 (5) | In a 1980s music video with several camera angles and edits, good lighting, and good audio features, the female band members play and sing a song that refers to hookahs and cigarettes. | |

| Overall portrayal of smoking | <.001 | ||||

| Positive | 16 (24) | A rock music video portrays attractive young white men and women who are smoking and drinking alcohol at a concert and back-stage while listening to music with lyrics that refer to alcohol, cigarettes, and partying. | 56 (92) | A male hookah bar owner in his 30s describes hookah bars as mellow, entertaining, and fun places to bring a date. He is standing next to a booth in which 2 college-aged women are smoking a hookah and doing tricks with smoke. | |

| Negative | 28 (42) | A middle-aged white male doctor stands in the hallway of what appears to be a doctor’s office and explains the negative physiological effects of smoking cigarettes. | 0 (0) | N/A | |

| Neutral | 22 (33) | A young white female musician plays the piano and sings a song with the lyrics “cause you’re my rock star, in between the sets, eyeliner and cigarettes.” | 5 (8) | A young woman plays the ukulele and sings a humorous song about the subject of the song’s future children discovering photos of their parent smoking hookah and doing other potentially embarrassing or controversial things. | |

| Association of smoking with positive characteristics | |||||

| Humor | 17 (26) | Three white British young men parody a well-known pop song with humorous lyrics about celebrities, teen culture, sexual jokes, and slapstick physical comedy. They refer to menthol cigarettes. | 7 (11) | Four men who are in their 20s and early 30s and are of different ethnicities compete in an Olympics-style race to determine who can be the first to properly set up, light, and smoke a hookah while “judges” comment and laugh. | .04 |

| Attractiveness | 12 (18) | In a vintage smoking advertisement, a young well-groomed woman, wearing a strapless dress and jewelry, smokes a cigarette and smiles and lifts her eyebrows at the camera after exhaling. | 9 (15) | Two flirtatious white college-aged women blow smoke rings and do other tricks with hookah smoke while a 30 year-old white man comments on their skills and tells how “hookah girls” help people enjoy hookah lounges. | .29 |

| Power | 5 (8) | In a montage of smoking scenes from a popular television series, young and middle-aged white businessmen and businesswomen who wear fashionable period clothes are shown smoking cigarettes. | 2 (3) | A man off camera uses masculine and derogatory language to demonstrate his command of hookah preparation and to provide instructions about setting up a hookah as a woman carries out his instructions. | .29 |

| Sexuality | 16 (24) | In a documentary on the spread of cigarette smoking in the United States, a white man in his 60s or 70s tells how cigarette smoking by women in early movies was used to characterize them as prostitutes or sexually immoral women. | 9 (15) | While sitting in a basement, a group of white college-aged men smoke hookah. One of them makes a sexual gesture with the hookah hose and raises his eyebrows suggestively as he smokes. | .18 |

| Sociability | 18 (27) | A man smokes a single cigarette in one drag, without exhaling, while his friends comment, laugh, and cheer him on in the background. | 22 (36) | While sitting at a kitchen table, 3 white college students (1 woman and 2 men) smoke hookah and talk about themselves and hookah smoking in talk-show style. | .29 |

| Exoticness | 0 (0) | N/A | 2 (3) | A middle-aged white male hookah bar owner talks about hookah smoking as part of Middle Eastern culture and discusses the history of hookah smoking. | .14 |

| Association of smoking with negative or health-related consequences | |||||

| Short-term health consequences | 33 (50) | A montage of people smoking in a popular television program shows several people coughing after inhaling cigarette smoke. | 11 (18) | In a cartoon video, Alice from Alice in Wonderland coughs and tries to fan hookah smoke away from her face when the caterpillar blows smoke in her direction. | <.001 |

| Long-term health consequences | 29 (44) | A middle-aged black man who is presenting a magic trick with cigarettes mentions that he does not smoke and says that if children are watching, they should not start smoking, because it is bad for people’s health and has been known to cause cancer. | 1 (2) | A college-aged white female sitting at her kitchen table with 2 college-aged white males says that hookah tobacco does not contain chemicals or tar but does contain nicotine. She says, “It’s not good for you, but we still like doing it.” | <.001 |

| Children smoking | 16 (24) | The video shows footage of a male Indonesian toddler smoking cigarettes while his parents and other people watch him, with narration by a male British reporter. | 1 (2) | In a cartoon video, Alice from Alice in Wonderland inhales second-hand hookah smoke from the hookah-smoking caterpillar. | <.001 |

| Antismoking message | 26 (39) | An educational video targeted at college students discusses the prevalence of cigarette smoking among college students and advises students to quit as soon as possible because cigarettes are “deadly as ever.” | 0 (0) | N/A | <.001 |

| How to quit smoking | 14 (21) | A middle-aged white man from the United States demonstrates how he is quitting cigarette smoking by using Nicorette™ gum. | 0 (0) | N/A | <.001 |

| Content | |||||

| Minimization of health risk | 8 (12) | A video advertisement for electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) promotes them as a healthier way to inhale nicotine than smoking regular cigarettes. | 11 (18) | A college-aged Arab-American man discusses electronic hookah charcoal, displays a box that says “No carbon monoxide,” and says there is less carbon monoxide in the electronic hookah charcoal than in regular hookah charcoal. | .35 |

| Brand reference or appeal | 22 (33) | Three white male teenagers sit in a basement or garage and smoke a specific cigarette brand, commenting on its qualities, availability, and price and discussing other topics as well. | 17 (28) | Two males in their late 20’s or early 30’s demonstrate how they made a special holiday hookah for a hookah website’s contest. They show the can of the specific brand of hookah tobacco that they used and show the name in the text. | .51 |

| Tricks | 10 (15) | A middle-aged white male magician does several tricks with cigarettes, including lighting the cigarette off his finger, making the cigarette disappear, smoking several cigarettes at once, and using a cigarette to light his arm on fire. | 32 (52) | In a video montage of a college-aged white man from the United States, the man blows smoke rings and does other tricks with hookah smoke while sitting in a bedroom with movie and pop-culture posters on the walls. | <.001 |

| How to smoke or set up a smoking device | 4 (6) | A documentary narrated by a middle-aged man shows how cigarettes are manufactured. | 25 (41) | In a video with lots of editing and electronic dance music playing, a young Asian woman demonstrates how to set up and smoke a hookah while the steps are described in text. | <.001 |

| Fetishism | 6 (9) | An attractive white female in her late teens, wearing a lacy lingerie top and underwear, lies on a bed close to the camera, with a box of cigarettes in front of her, smoking a cigarette and suggestively inhaling smoke and licking her lips. | 0 (0) | N/A | .02 |

| Music | 35 (53) | Rock music plays in the background of an advertisement for e-cigarettes. | 29 (48) | Hip-hop music plays in the background while a group of men of various ages and ethnicities smoke hookah together in a living room. | .54 |

| Music video | 18 (27) | A middle-aged black woman sings about chain smoking at night because her lover left and also sings that she could quit smoking cigarettes if her lover came back. | 4 (7) | A homemade music video of a song from the 1960s contains references to the hookah-smoking caterpillar from Alice in Wonderland. | .002 |

| Historical or documentary footage | 7 (11) | In a video with clips of old television cigarette commercials and World War II footage of soldiers smoking cigarettes, several narrators comment on the history of cigarettes and share personal anecdotes. | 1 (2) | A middle-aged white male hookah bar owner talks about hookah smoking as part of Middle Eastern culture and describes the history of hookah smoking. | .04 |

| Poetry | 1 (2) | As a middle-aged male poet describes important moments in his life when cigarettes were present, images pertaining to his story appear on the screen. | 1 (2) | The hookah-smoking caterpillar from Alice in Wonderland tells Alice a poem and illustrates it with images created with the hookah smoke. | .96 |

Abbreviation: N/A indicates not applicable.

For computation of percentages, individuals with indeterminate socio-demographic characteristics were not included.

Video Portrayal of Smoking

Of the 127 videos, 72 (57%) were coded as positive in their overall portrayal of smoking, 28 (22%) were coded as negative, and 27 (21%) were coded as neutral.

The portrayal was positive in far fewer cigarette-related videos than hookah-related videos (24% vs. 92%, P<.001); and while 28 of the cigarette-related videos were coded as negative, none of the hookah-related videos were coded as negative (42% vs. 0%, P<.001).

Although the 2 types of videos were similar in terms of portraying attractiveness, power, sexuality, sociability, and exoticness of tobacco use, the cigarette-related videos more commonly contained humor (26% vs. 11%, P=.04).

Of the 2 types of videos, the cigarette-related ones more commonly contained descriptions of short-term health consequences (50% vs. 18%, P<.001) and long-term health consequences (44% vs. 2%, P<.001), portrayed children smoking (24% vs. 2%, P<.001), contained explicit antismoking messages (39% vs. 0%, P<.001), and described how to quit (21% vs. 0%, P<.001).

About a third of cigarette-related videos (33%) and hookah-related videos (28%) contained product brand references. Cigarette-related videos less commonly described smoking tricks (15% vs. 52%, P<.001) and how to smoke (6% vs. 41%, P<.001) and more commonly contained fetish content (9% vs. 0%, P=.02). Nine (75%) of the 12 cigarette videos in the minimization of health risk category mentioned e-cigarettes. About half of all videos contained music. Of the 66 cigarette-related videos, 18 (27%) were coded as music videos. Few videos in either category contained historical or documentary footage or poetry.

DISCUSSION

Our analyses of 127 YouTube videos showed that hookah-related videos were more likely than cigarette-related videos to portray tobacco use in a positive light. In addition, while hookah-related videos were less likely to mention short- and long-term potential effects of tobacco use, to contain explicit antismoking messages, and to provide specific information on how to quit tobacco use, they were more likely to describe smoking tricks and provide practical information on how to smoke.

Our findings regarding the overall portrayal and health consequences of hookah use are consistent with previous research demonstrating that many individuals perceive hookah use to be safer than cigarette use.34-37 On the one hand, this misperception may stem from the kinesthetic aspects of the hookah experience, including the fruity aroma of the tobacco, lightness of the smoke, and coolness of the water.36-38 It is possible that Internet videos and similar media messages such as the ones we studied have played a role in enhancing or propagating popular myths associated with hookah use. This would be in keeping with cultivation theory, which posits that messages and imagery in popular media may subsequently alter viewers’ perceptions.39 However, it may also be simply that the newness and ceremony related to hookah encourage people to show how to use it.

Our study was similar to Forsyth and Malone’s study in terms of sample size and several of the content categories.16 However, our study found 42% of cigarette-related videos to be negative, whereas their study found only 16% to be negative. This could be because our study was performed more recently. Over the past few years, factors such as the passage of multiple clean air laws may have shifted the types of videos posted. In addition, an increasing number of products (e.g., e-cigarettes) are being marketed to help people stop smoking regular cigarettes, and videos related to these “harm reduction” products often vilify traditional tobacco use. Our sample included a slightly higher number of e-cigarette videos than that mentioned in Forsyth and Malone’s article (9 vs. 5). As described in our methods, when both e-cigarettes and traditional cigarettes were present in a video, we focused on coding the portrayal of traditional cigarettes. Because videos containing e-cigarettes tended to vilify traditional cigarettes, they were often coded as “negative” overall portrayal.

Although people watched cigarette-related videos more frequently than hookah-related videos, they were more likely to comment on the hookah-related videos. This pattern is consistent with the view that cigarette smoking is a more established, mainstream behavior and that hookah users are part of an emerging subculture. It is also consistent with the tendency we found for hookah-related videos to be homemade and poorly produced. Interestingly, many creators of hookah-related videos mentioned receiving, or specifically asked to receive, free hookah tobacco products from popular hookah tobacco companies in exchange for doing YouTube reviews of these products. This new form of word-of-mouth advertising is becoming a popular and effective way for companies to reach a target audience and gain loyal customers.40 Internet user–generated advertising such as this has the potential to reach millions of viewers without the cost of traditional advertising while also circumventing policies about tobacco advertising.

In our study, we found that while cigarette-related videos had a tendency to be associated with positive individual characteristics such as a sense of humor, both cigarette- and hookah-related videos were most commonly associated with social aspects of the experience of smoking (27% and 36%, respectively). This is consistent with findings in previous qualitative studies of cigarette and hookah smoking, which suggest that the social aspect is important.34-36 Given that hookah use did not originate in the United States, it might seem that it would be more likely to be associated with exoticness than cigarette use, but we did not find this to be the case in our study. This may indicate that hookah use is rapidly becoming accepted as part of the US culture.

Hookah-related videos were more likely than cigarette-related videos to focus on how to smoke, probably because there are more steps necessary to prepare a hookah, including filling it with water, loading the tobacco, covering the tobacco in aluminum foil and punching holes in it, and lighting a piece of charcoal to place atop the tobacco. Some videos framed hookah preparation as an art form or hobby that requires patience and experience to cultivate and perfect. The presentation of hookah use as a complex social ritual that creates and entrains unique social structures within its bounds may add to the compelling nature of hookah tobacco smoking.41 Videos such as the ones we assessed may help individuals display expert status in the hookah smoking community and receive reinforcement through viewer comments and feedback.

There was a greater than expected number of cigarette-related videos that involved children smoking. The vast majority of these involved the same child, a 2-year-old Indonesian toddler who had become a tourist attraction.42 The presence of videos involving this individual may have skewed our results by increasing, for example, the percentage of cigarette-related videos coded for negative overall portrayal of tobacco and “dislike.” However, we included these videos in our sample in order to consistently apply our selection criteria.

Public health practitioners and educators may benefit from recognizing the potential importance of YouTube videos as a source of information about tobacco use. They may also find it valuable for their educational programs to emphasize that the product used in hookahs is in fact tobacco and that the smoke from hookahs contains combustion products similar to the smoke from cigarettes. However, they should recognize that the aesthetic appeal of hookah use—including the sweet-smelling smoke, the attractive apparatus, the mildness of the experience relative to cigarette smoking, and the belief that the water somehow filters toxins—makes it challenging to persuade people of its potential harm and addictiveness. It may also be valuable for public health practitioners to consider using the medium of Internet user–generated videos (social marketing) to improve public health. Although this may provide an opportunity to reach many individuals at a relatively low cost, we did not find any hookah-related videos produced by public health practitioners.

Limitations

Studies of Internet user–generated content sites are inherently limited because access to them represents only one point in time, and search term returns are dependent on self-labeling of video descriptions, tags, and category by their creators. We tried to minimize this limitation by sampling from the most popular video-sharing site (YouTube), using 2 different methods to sample (by popularity and relevance), sampling on 2 occasions and using 2 different search terms. Nevertheless, our results may not be generalizable to other samples of user-generated and posted videos, especially over time. Another limitation is that subjectivity is inherent in the coding of variables such as production quality and association with humor. To minimize subjectivity, we developed a comprehensive codebook with detailed criteria for codes, we had 2 people code each video, and we adjudicated the coding in cases of coding disagreement. When we computed interrater reliability, we found it to be high. Finally, our coding of the gender, age, and race of video narrators was based on assumptions about their appearance and may not correspond to how they self-identify.

Conclusions

Our study of a sample of popular YouTube videos regarding cigarette smoking and hookah tobacco smoking shows that hookah-related videos are more likely to portray tobacco use as positive, less likely to describe short- and long-term harms of tobacco use, and more likely to offer practical information on how to prepare and smoke tobacco. It may be valuable for public health practitioners and educators to emphasize the similarities rather than the differences between cigarette and hookah use. It may also be valuable for them to use video Web sites such as YouTube to reach the public.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS.

Young people forming attitudes and perceptions regarding tobacco use are heavily exposed to internet videos. Compared with cigarette-related videos, hookah-related videos are substantially more likely to portray tobacco use in a positive light, less likely to mention short- and long-term consequences of tobacco use, to contain explicit antismoking messages, and less likely to provide specific information on how to quit tobacco use.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Steven Farley and Erica DePenna for their assistance with coding and transcribing.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant number R01-CA140150 to B. A. Primack.

Footnotes

Contributorship Statement

MC and BP conceived of the study. MC and AS obtained the data. AS and BP conducted the analyses. MC wrote the first draft. BP wrote additional portions of the first draft. BP provided supervision. MC, AS, and BP contributed important intellectual content to revision of the manuscript. MC, AS, and BP approved the final version. BP, AS, and MC had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Human Participant Protection

Institutional Review Board exempt (category involving publicly-available existing data).

Competing Interests Statement

The authors have no competing interests to report.

References

- 1.Barnett TE, Curbow BA, Weitz JR, Johnson TM, Smith-Simone SY. Water pipe tobacco smoking among middle and high school students. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(11):2014–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.151225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cobb C, Eissenberg T, Primack BA. Tracking Waterpipe Tobacco Smoking Prevalence on a U.S. College Campus. Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco Annual Meeting; Dublin, Ireland. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Primack BA, Sidani J, Agarwal AA, Shadel WG, Donny EC, Eissenberg TE. Prevalence of and associations with waterpipe tobacco smoking among U.S. university students. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36(1):81–86. doi: 10.1007/s12160-008-9047-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jordan HM, Delnevo CD. Emerging tobacco products: Hookah use among New Jersey youth. Preventive Medicine. 2010;51(5):394–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Primack BA, Walsh M, Bryce C, Eissenberg T. Water-pipe tobacco smoking among middle and high school students in Arizona. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):e282–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smith-Simone S, Maziak W, Ward KD, Eissenberg T. Waterpipe tobacco smoking: Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and behavior in two U.S. samples. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(2):393–8. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shihadeh A, Saleh R. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, “tar”, and nicotine in the mainstream smoke aerosol of the narghile water pipe. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2005;43:655–61. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sepetdjian E, Shihadeh A, Saliba NA. Measurement of 16 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in narghile waterpipe tobacco smoke. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2008;46:1582–90. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. TobReg Advisory Note: Waterpipe tobacco smoking: health effects, research needs and recommended actions by regulators. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katurji M, Daher N, Sheheitli H, Saleh R, Shihadeh A. Direct measurement of toxicants inhaled by water pipe users in the natural environment using a real-time in situ sampling technique. Inhalation Toxicology. 2010;22(13):1101–09. doi: 10.3109/08958378.2010.524265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eissenberg T, Shihadeh A. Waterpipe tobacco smoking and cigarette smoking: A direct comparison of toxicant exposure. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;37(6):518–23. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aljarrah K, Ababneh ZQ, Al-Delaimy WK. Perceptions of hookah smoking harmfulness: predictors and characteristics among current hookah users. Tobacco Induced Diseases. 2009;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1617-9625-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martinasek MP, McDermott RJ, Martini L. Waterpipe (Hookah) Tobacco Smoking Among Youth. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2011;41:34–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ciolli A. Joe Camel meets YouTube: Cigarette advertising regulations and user-generated marketing. University of Toledo Law Review. 2007;39:121. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elkin L, Thomson G, Wilson N. Connecting world youth with tobacco brands: YouTube and the internet policy vacuum on Web 2.0. Tobacco Control. 2010;19(5):361–6. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.035949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forsyth SR, Malone RE. “I’ll be your cigarette-Light me up and get on with it”: Examining smoking imagery on YouTube. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12(8):810–16. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Google Ad Planner. [December 17, 2011];Top 1000 most-visited site on the web. http://www.google.com/adplanner/static/top1000/

- 18.YouTube. [December 17, 2011];YouTube Timeline. http://www.youtube.com/t/press_timeline.

- 19.Basu S. [December 17, 2011];How to Find and Participate in YouTube Contests. http://www.makeuseof.com/tag/find-participate-youtube-contests/

- 20.Dalton MA, Sargent JD, Beach ML, Titus-Ernstoff L, Gibson JJ, Ahrens MB, et al. Effect of viewing smoking in movies on adolescent smoking initiation: a cohort study. Lancet. 2003;362(9380):281–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13970-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sargent JD, Beach ML, Adachi-Mejia AM, Gibson JJ, Titus-Ernstoff LT, Carusi CP, et al. Exposure to movie smoking: its relation to smoking initiation among US adolescents. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1183–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charlesworth A, Glantz SA. Smoking in the movies increases adolescent smoking: a review. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1516–28. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gidwani PP, Sobol A, DeJong W, Perrin JM, Gortmaker SL. Television viewing and initiation of smoking among youth. Pediatrics. 2002;110(3):505–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Took KJ, Weiss DS. The relationship between heavy metal and rap music and adolescent turmoil: real or artifact? Adolescence. 1994;29(115):613–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeman B, Chapman S. Is “YouTube” telling or selling you something? Tobacco content on the YouTube video-sharing website. Tobacco Control. 2007;16:207–10. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Madan A, Frantzides C, Pesce C. The quality of information about laparoscopic bariatric surgery on the Internet. Surgical Endoscopy. 2003;17:685–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gordon J, Barot L, Fahey A, Matthews M. The internet as a source of information on breast augmentation. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2001;107:171–6. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200101000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leighton H, Srivastava J. First 20 precision among World Wide Web search services. Journal of the American Society for Information Science. 1999;50(10):870–81. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing Qualitative Research. 3. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller WL, Crabtree BF. Primary care research: a multi typology and qualitative road map. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. London, England: Sage Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Austin EW, Pinkleton B, Fujioka Y. Assessing prosocial message effectiveness: effects of message quality, production quality, and persuasiveness. J Health Commun. 1999;4(3):195–210. doi: 10.1080/108107399126913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sly DF, Heald GR, Ray S. The Florida “truth” anti-tobacco media evaluation: design, first year results, and implications for planning future state media evaluations. Tob Control. 2001;10(1):9–15. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative resarch in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Meth. 2008;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammal F, Mock J, Ward KD, Eissenberg T, Maziak W. A pleasure among friends: how narghile (waterpipe) smoking differs from cigarette smoking in Syria. Tob Control. 2008;17(2):e3. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.020529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakkash R, Khalil J, Afifi RA. The rise in narghile (shisha, hookah) waterpipe tobacco smoking: A qualitative study of perceptions of smokers and non smokers. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:315. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roskin J, Aveyard P. Canadian and English students’ beliefs about waterpipe smoking: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khalil J, Heath RL, Nakkash RT. The tobacco health nexus? Health messages in narghile advertisements. Tob Control. 2009;18:420–21. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.030148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rastam S, Ward KD, Eissenberg T, Maziak W. Estimating the beginning of the waterpipe epidemic in Syria. BMC Public Health. 2004;4:32. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-4-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gerbner G, Gross L, Morgan M, Signorielli N. Living with television: The dynamics of the cultivation process. In: Bryant J, Zillman D, editors. Perspectives on media effects. Hilldale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1986. pp. 17–40. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Trusov M, Bucklin RE, Pauwels K. Effects of Word-of-Mouth Versus Traditional Marketing: Findings from an Internet Social Networking Site. Journal of Marketing. 2009;73(5):90–102. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Collins R. Interaction Ritual Chains. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 42.YouTube. [January 18, 2012];Indonesian baby on 40 cigarettes a day. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x4c_wI6kQyE.