Abstract

Mutation of tumor suppressor gene Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) is an initiating step in most colon cancers. This review summarizes Apc models in mice and rats, with particular concentration on those most recently developed, phenotypic variation among different models, and genotype/ phenotype correlations.

Keywords: Adenomatous polyposis coli, APC, Apc mouse models, Apc rat models, Apc models, Apc rodent models, FAP models, Apc alleles, Conditional Apc mutations, Intestinal polyposis, LOH / Apc mouse model, Intestinal polyposis in mice, Apc associated tumors, Apc and development

Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)

Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) is a critical tumor suppressor gene in the colon. Humans with germline APC mutation develop hundreds to thousands of colon tumors in their first few decades of life, a condition referred to as familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). These tumors are pre-cancerous, and prophylactic colon removal is recommended to avoid progression to invasive carcinoma that otherwise would occur in FAP patients by age 39, on average [1–4]. Notably, APC mutation is also an early if not the first step in the development of more than 80% of all sporadic colorectal cancers [5, 6]. In both inherited and sporadic colorectal cancer, APC mutations result in premature truncation of the large (2843 amino acid) APC protein, eliminating roughly half to three-quarters of the C-terminal portion [7, 8]. APC interacts with multiple proteins and participates in diverse cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, adhesion, and migration. One of the first reported APC functions is as a Wnt-signal antagonist. In this capacity, APC forms a complex with GSK3β, axin, and other proteins to mediate phosphorylation and eventual proteasomal destruction of the oncoprotein β-catenin [7, 9]. Animal models have been generated to study APC functions in development and tumorigenesis including Drosophila, C.elegans, zebrafish, mouse, rat and pig.

Apc mouse models

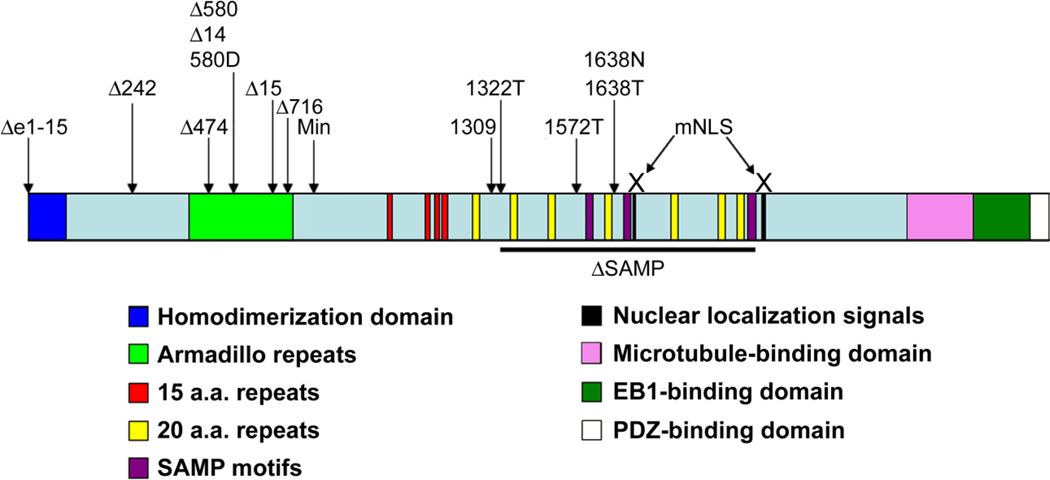

With similar physiological and pathological processes to humans, [10] mice are particularly well-suited to study Apc functions in intestinal homeostasis, tumor suppression, and vertebrate development [11]. All characterized motifs in human APC are conserved in murine Apc and the proteins are 87.9% identical and 91.9% similar at the amino acid level [12]. Furthermore, intestinal tumors from Apc mutant mice displayed expression signatures similar to that in tumors from humans with germline APC mutations [13]. Apc mouse models can be divided into two broad categories: mice with a germline Apc mutation that results in protein truncation, alteration, or reduced expression in all tissues and mice with conditional Apc alterations only in a specific tissue at a particular stage of development. Figure 1 shows the structural domains of Apc and germline mutations in mice. Here, we compare and contrast the published phenotypes of the 43 different Apc mouse models described to date, with particular emphasis on studies from the past several years.

Figure 1.

Apc protein structure and different rodent models with germline Apc mutations

ApcMin/+

The Multiple intestinal neoplasia (Min) mouse was identified in an ethylnitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis screen and has a nonsense mutation that results in truncation of Apc at codon 851 [14, 15]. Since its first description in 1990, the ApcMin model has been used extensively to study Apc functions in suppression of intestinal tumorigenesis and to investigate tumor prevention strategies. Mice homozygous for ApcMin die early in embryonic development. In the C57Bl/6 background adult ApcMin/+ mice live for ~120 days and display both intestinal (100% penetrant) and extra-intestinal phenotypes [12, 16–18]. ApcMin/+ mice typically develop between 20–100 polyps in their gastrointestinal tract [17]. Differences in diet, flora, genetic background, and genetic modifiers can result in even greater variability in the polyp multiplicity [19–21]. The vast majority of ApcMin/+ polyps are in the small intestine, with a few developing in the colon and even fewer in the stomach [16, 17]. Histologically, most tumors in ApcMin/+ mice are benign adenomas: polypoidal, sessile, or papillary in nature, with limited dysplasia and atypia. Although these polyps can reach 8 mm in diameter, malignant changes are not typically seen. However, in older ApcMin/+ mice, polyps express molecular markers of invasiveness seen in malignant tumors, [21] and areas with limited invasion and carcinoma in situ have been observed [17]. Furthermore, ApcMin/+ mice in certain genetic backgrounds live longer and develop fewer polyps than do mice in the B6 background, but show malignant changes and local metastasis to lymph nodes [22]. Likely the short life span of ApcMin/+ mice limits the accumulation of other genetic mutations in intestinal tumors that are required for progression to invasive carcinoma [22].

In both ApcMin/+ mice and FAP patients, mutation of the wild-type Apc allele (or ‘second hit’) is required for adenoma formation [23]. Genetic and environmental factors that raise mutation rate increase polyp multiplicity in ApcMin/+ mice [24–27]. However, the nature and predicted mechanism of this second mutation is different in ApcMin/+ mice and in human FAP patients. In humans with FAP, the somatic APC mutation is frequently an independent protein-truncating point mutation. LOH can also occur, presumably by mitotic recombination and particularly in adenomas from the distal bowel when the germline mutation truncates APC at or near codon 1309 [28]. In contrast, most of adenomas from ApcMin mice show LOH at the Apc locus and the most recent evidence supports loss of the wild-type Apc allele with locus diploidy as the mechanism of this LOH [23, 29]. Whether this LOH is the result of somatic recombination or loss and duplication of the entire chromosome 18 (the location of Apc) is still not completely resolved. Evidence for somatic recombination as the underlying mechanism of this LOH came from analysis of ApcMin/+ mice with a Robertsonian translocation, fusing acrocentric chromosomes 7 and 18 (Rb9 fusion). When placed in trans, cis, or in homozygous distribution with the ApcMin allele, the Rb9 chromosome was associated with reduced tumor burden in ApcMin/+ mice [29]. Because mitotic recombination is compromised in Rb9 mice, it was concluded that somatic recombination is the mechanism of LOH required for polyp formation. However, there is a chance that the Rb9 chromosome also affects chromosomal segregation and thus, complete loss and duplication of chromosome 18 in adenomas from ApcMin/+ mice without the Rb9 chromosome is still a possibility.

An elaborate experiment that assessed polyp formation in mice with ApcMin and mutant Atp5a1 alleles (both genes are found on chromosome 18) implicated loss and duplication of the entire chromosome 18 as the mechanism of LOH in polyps from ApcMin/+ mice [30]. Homozygous mutation of Atp5a1 is lethal to cells. Fewer polyps were observed in mice with both mutant Atp5a1 and ApcMin alleles are on the same chromosome than in mice with trans-distributed mutant Atp5a1 and ApcMin alleles. Furthermore, when compared to polyps from ApcMin/+ mice harboring a wild-type Atp5a1 allele, the distribution and histopathological characteristics of polyps were different in mice with Apc and Atp5a1 mutations in cis distribution, but not in trans. When mutations in Apc and Atp5a1 are in cis, complete loss of chromosome 18 with or without subsequent duplication results in nonviability since homozygosity for mutant Atp5a1 is lethal. In contrast, there would not be this selection against loss and reduplication of the whole chromosome if mutated Apc and Atp5a1 are in trans. Since polyps formed in the latter situation were indistinguishable from those that developed in ApcMin/+ mice with wild-type Atp5a1 alleles, it was concluded that loss and duplication of chromosome 18 is the primary mechanism of LOH in polyps from ApcMin/+ mice [30]. One potential caveat for consideration is that, because chromosome 18 is acrocentric, a single somatic recombination proximal to the Apc locus would be difficult to distinguish from complete loss and reduplication of the whole chromosome [29].

In addition to intestinal tumors, ApcMin/+ mice develop mammary tumors, but at a much lower penetrance (5%) and at a relatively older age (16 ±3.5 weeks) [18]. Histologically, mammary tumors are usually invasive in nature, with areas of adenocarcinoma and adenoacanthoma, the latter of which have not been reported in humans [18]. ApcMin/+ mice treated with the mutagen ENU, exposed to X-rays, or with a mutation in the DNA repair gene Myh, have increased mammary tumor incidence but the same tumor morphology, indicating that Apc mutation alone is not sufficient for mammary tumorigenesis [26, 31]. In mice with wild-type Apc, mammary expression of stabilized β-catenin results in tumor development, consistent with a role for Apc in inhibiting mammary tumorigenesis via antagonizing the Wnt signaling pathway [18, 32, 33]. Although humans with FAP also have an increased risk of tumors outside the gastrointestinal tract, including desmoid tumors, mandibular osteomas, and retinal dysplasias, they do not show increased susceptibility to breast cancer [34]. However, APC mutation or promoter methylation has been detected in up to 70% of human breast cancers surveyed [35–37]. Moreover, APC methylation status was significantly associated with decreased APC protein level and reduced disease-free survival in patients with invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast, supporting a role for APC in suppression of mammary neoplasia [38].

Although intestinal polyposis is the dominant feature of ApcMin/+ mice, these mice also show alterations in other tissues [17, 39]. There is no evidences that LOH is necessary for these extra-intestinal phenotypes of ApcMin/+ mice, which suggests that Apc haplo-insufficiency is the underlying mechanism. Anemia was the first such phenotype to be described in ApcMin/+ mice and was used to predict intestinal polyposis before the establishment of ApcMin genotyping [17]. Although the exact pathogenesis is not completely understood, anemia in ApcMin/+ mice is microcytic-hypochromic, consistent with chronic blood loss from intestinal lesions as the underlying cause [17]. Old ApcMin/+ mice also develop large spleens with enhanced splenic hematopoiesis, therefore, larger spleens might be an extra-medullary compensatory response to anemia. However, because larger spleens and anemia are not always correlated in ApcMin/+ mice, a different mechanism for large spleen development might be at play [39]. Old ApcMin/+ mice can also develop myelodysplastic disease, with increased formation of myeloid, granulocytic, and erythroid colonies in the spleen [40, 41]. Other hematological changes seen in ApcMin/+ mice include rapid thymus regression, depletion of splenic natural killer (NK) cells, and loss of B-lymphocyte progenitors in spleen and bone marrow [42]. In ApcMin/+ mice the bone marrow micro-environment appears disrupted and gradual loss of the quiescent hematopoietic stem cells occurs [41].

Gonadal changes in ApcMin/+ mice include increased numbers of degenerated and undeveloped ovarian follicles, and under-developed testicular seminiferous tubules, the cause of which is not known [39]. However, conditional truncating Apc mutation in testicular Sertoli cells results in premature germ-cell loss and the absence of both Sertoli cell apical extensions and the blood-testis barrier. These changes were not recapitulated by activating mutations in β-catenin, consistent with a Wnt-independent Apc function [43]. Disruption and involution of mammary glandular structures has been reported in pregnant ApcMin/+ mice, along with altered proliferation, increased apoptosis, and interrupted epithelial integrity and polarization of mammary epithelial cells. Because these alterations occur in the absence of changes in Wnt target transcript levels and nuclear localization of β-catenin, these mammary gland phenotypes appear to be Wnt-independent [44]. Finally, at 15 weeks, ApcMin/+ mice display a change in their serum lipid profile called dyslipidemia, with increased serum levels of triacylglycerol, cholesterol, and free fatty acids. The exact cause of this dyslipidemia is unknown, but hyperlipidemia has been correlated with the activity and level of the lipid regulatory nuclear receptors PPAR α, β and γ [45–47]. Treatment of ApcMin/+ mice with the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agent indomethacin decreases polyp number and also improves dyslipidemia in ApcMin/+ mice [48]. These extra intestinal phenotypes indicate that Apc functions not only in intestinal epithelial cells, but also in development and maintenance of other tissues.

In addition to its use as a model of FAP, ApcMin/+ mice have been used extensively as a tumor susceptibility model to test the effect of environmental factors, mutations in other genes, and drugs on intestinal tumorigenesis. Such studies have increased our understanding of both intestinal tumorigenesis and cancer biology in general and are summarized in several excellent reviews [11, 19, 49, 50].

Phenotypic variation in ApcMin/+ mice of different genetic backgrounds allowed elucidation of modifier genes that can enhance or attenuate intestinal polyposis, called Modifiers of Min (Mom) [19, 50]. Some Mom genes are found on chromosome 18. Some modifiers are single genes, others are thought to represent contiguous genes, and some remain less well-defined [50–54]. The modifiers appear to function as recessive, dominant, or semi-dominant loci. Some modifier genes, such as Mom-1 (Pla2g2a), work in a cell-non-autonomous manner [55, 56]. Others, like Mom-2 (Atp5a1), appear to inhibit loss of the wild-type Apc allele [30]. A detailed discussion of the mechanisms of these modifiers can be found elsewhere [50].

Mouse models expressing truncated Apc protein longer than ApcMin

APC is a large multi-domain protein that has been implicated in many cellular activities in addition to its role in down-regulating Wnt signaling. APC domains involved in targeting β-catenin for degradation are in the middle region of APC. Interaction of C-terminal APC regions with DNA and with microtubules has been proposed to contribute to tumor suppression [57, 58]. Disruption of the interaction between APC and microtubules affects spindle formation and mitosis in colon cancer cell lines and in intestinal epithelial cells in ApcMin/+ mice [59]. In addition, ApcMin/Min embryonic stem (ES) cells show chromosomal instability (CIN) [60]. These observations led to the proposal that loss of the C-terminal one third of APC would promote intestinal tumorigenesis [60–62]. To test this hypothesis, three mouse models with truncations of the C-terminal third of APC have been generated; Apc1638N, Apc1638T, and Apc1572T. The Apc1638N mouse was generated by insertion of a neomycin-resistance gene at Apc codon 1660. Apc1638N/1638N mice die as embryos. Apc1638N/+ mice develop intestinal polyps, but very few (less than 10) compared to the number in ApcMin/+ mice, and with a different distribution (gastric and colonic). Intestinal tumors in Apc1638N/+ mice are also invasive, with distant metastasis in the liver detected in one mouse. Because Apc1638N/+ mice live longer than ApcMin/+, mice, the invasive phenotype could reflect tumor progression over time. Intestinal tumorigenesis is enhanced in Apc1638N/+ mice with mutations in other tumor suppressor genes [63–67]. It was initially suggested that LOH in tumors from Apc1638N mice resulted from loss of the entire chromosome 18 [68]. However, more recent evidence indicates that the Apc+ allele appears to be maintained in most polyps from Apc1638N/+ mice, consistent with inactivation or silencing of the wild-type Apc allele [69]. One hundred percent of Apc1638N/+ mice develop desmoid tumors and cutaneous cysts [70]. In humans, desmoid tumors occur in FAP patients [71] and also in patients with an attenuated form of FAP (AFAP) resulting from germ-line mutations in the 3’ portion of APC [72]. AFAP patients develop only a few polyps, mainly in the duodenum [72–74]. Since only full-length and not truncated Apc protein is detected in these mice using Western blot, Apc1638N may be considered an essentially null allele [75]. The antibiotic selection cassette used to generate the Apc1638N mice was inserted in reverse orientation and it is thought that production of an antisense Apc transcript might lead to inhibition of the truncated Apc translation. Alternatively, the mild intestinal polyposis phenotype may indicate that the truncated Apc protein is not completely absent, but rather its level is below detection limits due to reduced expression or increased instability of the truncated protein. Possibly, this truncated Apc protein with multiple remaining β-catenin binding and degradation domains can suppress intestinal tumorigenesis in these mice.

In contrast to Apc1638N/+ mice, truncated Apc is expressed in Apc1638T mice, which have the antibiotic-resistance gene (hygromycin) inserted in the same position as in Apc1638N mice, but in the sense orientation [76]. Unexpectedly, Apc1638T/1638T mice are viable and do not develop intestinal or extra-intestinal tumors. Instead, these mice display post-natal growth retardation and nipple-associated cutaneous cysts, and lack preputial glands. The molecular basis for these phenotypes has not been determined, but they indicate a role for the C-terminal region of Apc in development [76]. Apc1638T/1638T mice also show larger thyroid follicles, accumulation of thyroglobulin in the endoplasmic reticulum and less response to exogenous thyroid stimulating hormone relative to wildtype mice [77]. It is puzzling that Apc1638N/1638T and ApcMin/1638T mice are not viable. The Apc1638T protein retains all 15 a.a. repeats, 1 of 3 SAMP motifs, and 3 of 7 20-a.a. repeats. Apc1368T/1638T embryonic stem (ES) cells have almost no change in Wnt signaling level while Wnt signaling is upregulated in Apc1638T/1638N ES cells [76]. Perhaps the remaining functions of the truncated Apc1638T allele are dose-dependent, and thus, the Apc1368T allele is haplo-insufficient for β-catenin regulation.

More recently, the Apc1572T mouse model was generated by deleting the remaining SAMP repeat in the Apc1638T mouse [78]. Although the truncated Apc protein in Apc1572T/+ mice is only 66 amino acids shorter than Apc from Apc1638T mice, the phenotypes of these two mouse models could not be more different. Unlike Apc1638T, Apc1572T germ-line homozygosity is incompatible with viability. One remarkable feature of Apc1572T/+ mice on a B6 background is that they develop no intestinal tumors, but instead develop invasive mammary tumors that can even metastasize to the lungs. While mammary tumor morphology is similar in both Apc1572T/+ and ApcMin/+ mice, the incidence of mammary tumors is much higher in Apc1572T/+ mice; 100% in virgin females and 30% in males compared to only 5% in ApcMin/+ females. β-catenin activity, as assessed using a “TOPFLASH” reporter assay, is higher in Apc1572T/1572T ES cells than in wild-type or Apc1638T/1638T ES cells, but lower than in Apc1638N/1638N ES cells. Apc1572T/+ mice do develop intestinal polyps if they also have a Smad4Sad allele, which results in defective TGF-β signaling [78]. Because the TGF-β pathway inhibits Wnt signaling [79], the authors propose that development of a mammary tumor requires a low level of Wnt signaling which is provided by the Apc1572T allele. Higher Wnt signaling resulting from reduced TGFβ signal, or from a second mutant Apc allele, promotes intestinal polyp formation. Although this model might explain the development of intestinal polyps in mice heterozygous for both Apc1572T and Smad4Sad [80], it does not explain the high penetrance of mammary tumors in these mice, given the low penetrance of mammary tumors in other models with higher Wnt signaling.

In conclusion, data collected from Apc1572T and Apc1638T mice implicates the C-terminal portion of Apc in control of mammary tumorigenesis and development. However, these models provide no direct evidence that the Apc C-terminal region suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis.

Apc1309 and Apc1322T/+ mice

Although ApcMin/+ mice have been used to model APC mutation in humans, similarly sized APC truncations are uncommon in both inherited and sporadic human colon cancers. Mutations in APC associated with colon cancer typically truncate the C-terminal half of the protein, leaving the first 20-amino acid (20-a.a.) repeat intact in at least one APC allele [81]. As this 20-a.a. repeat can bind to β-catenin, one would anticipate differences in cells expressing shorter Apc truncations, such as ApcMin, and cells with longer APC (as in human CRC) [82, 83]. The Apc1309 and Apc1322T mouse models were generated to express truncated Apc that retains the first 20-a.a. repeat [81, 84, 85]. As with ApcMin/+, both Apc1309/+ and Apc1322T/+ mice develop polyps mainly in the small intestine, but these polyps are more proximal than those from ApcMin/+ mice. The levels of Wnt target gene transcripts are lower in polyps from Apc1322T/+ mice than in polyps from ApcMin/+ mice, as expected since the Apc1322T protein includes the first 20-a.a. repeat [86]. However, Apc1322T/+ mice develop more polyps (> 200 polyps by 12 weeks) and have more intestinal stem cells than do ApcMin/+ mice [84]. Together, these results support the “just right” hypothesis that predicts that inclusion of the first 20-a.a. repeat in truncated APC proteins will result in only slight elevation of Wnt signaling, which is more conducive to intestinal tumor growth than is elevation of Wnt signaling to a higher level [82]. Extra-intestinal phenotypes reported for Apc1322T/+ mice include anemia and large spleens, similar to ApcMin/+ mice [84]. In contrast, Apc1309/+ mice develop far fewer intestinal tumors (~ 35), mainly in the small intestine at the age of 12–14 weeks, and have hyperlipidemia that develops at an even earlier age than in ApcMin/+ mice [85, 87]. Potential explanations for this large discrepancy in polyp number between mouse models that differ in truncated APC length by only 13 amino acids include the influence of environmental factors, genetic background, and different technologies used to generate these mice. Table 1 summarizes the intestinal phenotype in different Apc mouse models with truncated Apc longer than ApcMin.

Table 1.

Intestinal phenotypes in mice with truncated Apc longer than that of ApcMin

| Mouse model |

Polyp number | ApcMin/+ Polyp number* |

Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apc1638N/+ | <10 | - | Malignant changes are detected in old mice | [75] |

| Apc1638T/+ | None | - | Viable homozygous mutant mice | [76] |

| Apc1572T/+ | None | - | [78] | |

| Apc1322T/+ | 192 (age 10–12 weeks) | 154 (age 110–130 days) | Majority of polyps are in the proximal 2/3 of the small intestine | [84, 86] |

| Apc1309/+ | 36.7±2.7 | - | [87] |

included in the same study

Mouse models expressing truncated Apc protein shorter than ApcMin

Seven mouse models with mutations upstream to that in ApcMin have been described. ApcΔ242 [88], ApcΔ474 [89], and ApcΔ716 [90–92] mice have Apc truncation mutations at codons, 242, 474, and 716, respectively, while ApcΔ580 [93], Apc580D [94], and ApcΔ14 [95] mice each have a deletion of exon 14, resulting in a frameshift and a nonsense mutation at codon 580. ApcΔ15 mice have a deletion of the last Apc exon and the 3’UTR region and have no detectable expression of the mutant allele [96]. These seven mouse models share many phenotypes with ApcMin/+ mice, including embryonic lethality in the homozygous state, and in heterozygous mice, development of anemia and intestinal polyps predominantly in the small intestine that are indistinguishable at the microscopic level [88–94, 96, 97]. Although polyp number varies between these seven models (Table 2), in most cases, direct comparative studies have not been performed. Mammary tumors have been reported for 14.3% of ApcΔ58018.5% of ApcΔ474, and 9% of ApcΔ14 mice [89, 93, 97].

Table 2.

Intestinal phenotypes in mice with truncated Apc shorter than that of ApcMin

| Mouse model |

Polyp number |

ApcMin/+ Polyp number* |

Notes | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ApcΔ716 | 256±55 | 1/3 of those in ApcΔ716 | [91] | |

| ApcΔ14 | 36±29 | 34±18 | More polyps in distal colon and rectum relative to ApcMin/+, number of polyps increases in germ-free environment | [97] |

| ApcΔ15/+ | 184.7 | - | Tumors are mainly in the ileum, no comparative data to ApcMin mice | [96] |

| ApcΔ580 | 120±37 | - | No full-length or truncated APC proteins were detected in polyps | [93] |

| Apc580D | ?? | - | [94] | |

| ApcΔ474 | 123±9.6 | No comparative data to ApcMin mice | [89] | |

| ApcΔ242 | 177±30 | 106±28 | [88] |

included in the same study

Is the variation in polyp number in these mouse models due to the progressive deletion of particular Apc domains (see figure 1)? The ApcΔ716 protein is 134 a.a. shorter than the ApcMin protein and lacks an additional portion of the armadillo repeat region. Although it is tempting to speculate that the three-fold increase in polyp number seen in ApcΔ716/+ mice compared to ApcMin/+ mice results from interruption of the armadillo repeat region, ApcΔ242/+ mice, which have a truncating Apc mutation that eliminates the entire armadillo repeat region, develop fewer polyps than ApcΔ716/+ mice. Moreover, ApcΔ580/+, Apc580D/+, ApcΔ14/+ and ApcΔ474/+ mice, which have truncating mutations in the middle of the armadillo repeat region, have reported intestinal polyp numbers similar to that seen in ApcMin/+ mice (Table 2).

Complete deletion of Apc

In human CRC, APC mutations are predominantly found in a region referred to as the mutation cluster region (MCR), and result in truncation of the C-terminal half of APC [98]. Complete deletion of APC has been reported in FAP syndrome only rarely [99, 100], leading to the hypothesis that truncated APC protein can enhance tumorigenicity in a dominant-negative manner. A mouse model with complete deletion of all 15 Apc exons (ApcΔe1–15) was generated to test the requirement of truncated APC for tumor formation [101]. ApcΔe1–15/+ mice develop intestinal polyps of the same distribution and morphology as those seen in ApcMin/+ mice, but with increased frequency. Polyps from ApcΔe1–15/+ mice had lower levels of Apc+ mRNA compared to normal tissue, consistent with a requirement for loss of the wild-type allele for intestinal tumor development, although this was not directly examined. ApcΔe1–15/+ mice also develop more severe anemia than ApcMin/+ mice, and one ApcΔe1–15/+ mouse developed a mammary tumor. Female ApcΔe1–15/+ mice showed more severe phenotypes than did males. Polyps from ApcΔe1–15/+ mice had lower mRNA levels of Wnt target genes Axin2, c-Jun, and β-catenin than polyps from ApcMin/+ mice [101]. Although puzzling in terms of the underlying mechanism and pathogenesis, this observation is consistent with the hypothesis that there is a level of Wnt signaling optimal for polyp formation, and signaling in excess of this level inhibits polyposis [101].

Apc mouse models with interstitial Apc mutations

Two mouse models have been recently described in which the engineered mutations result in changes within, rather than truncation of, Apc protein: ApcmNLS and ApcΔSAMP models.

ApcmNLS model

APC is perhaps best known as a Wnt signal antagonist. In this capacity, APC is a component of a cytoplasmic complex that targets the oncoprotein β-catenin for proteasomal degradation [7]. APC also shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, aided by at least 2 nuclear localization signals (NLS) and 5 nuclear export signals (NES) [102]. Studies using cultured cells indicate that APC and β-catenin can interact in the nucleus, resulting in transcriptional repression of Wnt target genes and inhibition of cellular proliferation [9, 103]. In addition, nuclear APC interacts with Topoisomerase IIα, a critical enzyme required for DNA replication and a target for traditional cancer chemotherapeutics [104]. APC also has a role in DNA repair and synthesis [105, 106]. To study the role of nuclear APC in tissue homeostasis and tumor suppression, a mouse model was generated in which nuclear import of Apc was compromised via the introduction of inactivating mutations into both NLSs (ApcmNLS) [107]. ApcmNLS/mNLS mice are viable, with no significant alteration in lifespan. Compared to Apc+/+ mice, intestinal epithelia from ApcmNLS/mNLS mice were more proliferative and showed higher levels of Wnt target gene mRNA. In addition, ApcMin/+ mice develop more and larger intestinal tumors when they also harbor the ApcmNLS allele (ApcmNLS/Min). Together, studies using the ApcmNLS model support a role for nuclear Apc in inhibition of proliferation, Wnt signaling, and tumorigenesis [107].

ApcΔSAMP model

The ApcΔSAMP mouse, with a deletion of Apc amino acids 1322 to 2005, was generated to delineate the contribution of the Apc C-terminus to tumor suppression [108]. This Apc deletion eliminates all but the first 20-a.a. repeat and all SAMP motifs, but retains the C-terminal region of Apc. Phenotypes of the Apc1322T/+ and ApcΔSAMP mice were similar with regard to polyp number, distribution, size, and morphology, severity of dysplasia, differentiated and stem cell populations, and expression of Wnt target genes. Thus, it appears that in the Apc1322T/+ model, the C-terminal region of Apc is not involved in suppression of intestinal adenoma [108].

Changing the level of Apc expression

Two Apc mouse models with reduced Apc expression were generated by inserting a neomycin cassette into Apc intron 13 in either reverse (ApcNeoR) or forward orientation (ApcNeoF) [109, 110]. The neomycin cassette disrupts an enhancer and reduces the level of full-length Apc expressed from the mutant allele to 20% of normal levels for ApcNeoR, and 10% for ApcNeoF. Each allele produces an embryonic lethal phenotype in the homozygous state. By the age of 15 months, ApcNeoR/+ and ApcNeoF/+ develop intestinal polyps with relatively low incidence (19% and 50%, respectively) and multiplicity (0.26±5.4 and 1.09±8.5 polyps per mouse, respectively). The polyps in ApcNeoR and ApcNeoF mice display loss of the wild-type Apc allele and have less β-catenin stability and accumulation of nuclear β-catenin than do polyps from ApcΔ716/+ mice [109, 110]. Thus, in mice, there appears to be a critical threshold level of Apc to support tumor suppression.

A transgenic mouse expressing truncated Apc

Based in part on the correlation of FAP severity with specific truncating APC mutations, and on the ability of truncated APC to bind to full-length APC, it was proposed that particular APC truncations act in a dominant-negative manner [111]. However, a direct test of this hypothesis revealed no increased polyp susceptibility in mice carrying a transgene encoding Apc amino acids 1–716, even though the truncated Apc protein was detected in intestinal cells. It is possible that the proposed dominant -negative activity of truncated Apc could not overcome functional Apc from two wild-type Apc alleles that could compensate for any deleterious effect of the truncated allele. To explore this possibility, the transgene for truncated Apc was introduced into ApcΔ716/+ mice [90]. Because intestinal tumor number, distribution, and morphology were the same in ApcΔ716/+ mice with and without the extra truncated Apc transgene, it was concluded that in this mouse model, truncated Apc does not act in a dominant-negative manner [90].

Conditional Apc mouse models

Mouse models with germline Apc mutations have been useful to probe many aspects of APC biology, especially in intestinal tumorigenesis. However, most of these models are limited by a short life span, the predominance of intestinal phenotypes, and embryonic lethality in the homozygous state. To study functions of APC at different developmental stages and in organs other than the intestine, investigators have developed mice with conditional Apc mutations [112]. A critical component of most conditional systems is CRE recombinase, which induces recombination between two loxP1 sites, resulting in excision of the DNA between these sites. In conditional Apc mouse models, loxP1 sequences are inserted into introns of the mouse Apc gene flanking particular exon(s). In the presence of Cre, excision of the lox-flanked DNA leads to a frameshift mutation and truncation of Apc. Five different conditional Apc alleles have been made; Apc580S, ApcCKO, ApcΔex14, Apc15flox and Apclox468 [93–96, 113, 114]. The specificity of these Apc mutations is achieved by placing Cre under control of a tissue- or developmental stage-specific promoter or an inducible promoter, or by infecting tissues with Cre-expressing Adenovirus [115]. Table 3 summarizes different conditional Apc mouse models.

Table 3.

mice with conditional mutations in Apc

| Apc580S allele; Expression of Cre recombinase results in excision of Apc exon 14 and a stop codon at a.a. 580 | [94] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse | Organ | Developmental stage |

Cre delivery/phenotype | Ref |

| Apc580S | Colon and rectum | Adult | Cre delivered via Adenovirus vector injected in the colon through the anus. Develop colon adenomas in the distal 3 cm of the colon. Malignant transformation seen in old lesions. | [94] |

|

CPC;Apc CDX2P 9.5-NLS-Cre; Apc+/loxP) |

Distal ileum, cecum, colon and rectum | Day 8.5 embryonic | Cre is expressed using 9.5-Kb DNA fragment from the homeobox gene Cdx2 promoter. Mice develop ~10 tumors in ileum, cecum and colon by the age of 300 day. Malignant transformation in 66.1% of mice. Mice show anemia and stunted growth. |

[132] |

| CDX2P9.5-G22Cre; Apcflox/flox | Distal ileum, cecum, colon and rectum | Day 8.5 embryonic | Cre is expressed using 9.5-Kb DNA fragment from the homeobox gene Cdx2 promoter. There is a string of 22 guanine nucleotides after the ATG initiation codon (out of frame). Restoration of in-frame sequence occurs by mitotic microsatellite instability. Mice die at age of 10–27 days and develop large number of adenomatous polyps in the distal ileum and large intestine. |

[133] |

| AhCre-Apcfl/fl | Small intestine, large intestine. Possibly the liver | Adult | Cre expressed using Cyp1A promoter when mice were injected with β-naphthoflavone. Upregulation in Wnt signaling. Intestinal cell differentiation, proliferation, migration, and apoptosis disrupted. Mice died 4 days after induction. | [129] |

| MMTV-Cre-Apcflox/flox Ptenflox/flox | Salivary glands | ?? | Cre expressed using MMTV promoter. In B6X129 background, MMTV promoter is active in salivary gland and less active in mammary gland. Salivary gland tumors only with Pten deletion. | [117] |

| Mx1-Cre+ Apcfl/fl | Hematopoie tic stem and progenitor cells transplanted into WT mice | Adult | Cre expressed under the type-1 interferon inducible promoter Mx1 after injection of polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid (pI-pC). This promotor is active in other tissues including; intestinal epithelium, oseoblasts and kidney. To restrict the expression in only hematopoetic stem cells and progenitor cells, bone marrow cells from Mx1-Cre+ Apcfl/fl mice were implanted into WT mice. Induction of Cre results in increased cell cycle entry, apoptosis and exhaustion of hematopoetic and depletion of myeloid progenitor pool |

[126] |

| Ksp-Cre Apc58S/580S | Renal tubular epithelial cells and developing genitourinary tract | Embryonic | Cre is expressed using Ksp-cadherin promoter. Neonatal death with signs of renal failure. Rare mice that live to adulthood develop renal cysts, adenoma and elevated blood urea level | [125] |

| AhCre-Apcfl/fl | Kidney | Day 14.5–18.5 embryonic | Cre is expressed using Cyp1A promoter with no β-naphthoflavone induction. Renal carcinoma in ~1/4 mice at 6 months, increased incidence with co-existence of p53 mutations | [128] |

| OC-Cre Apcflox/flox | Osteoblasts | Starting from embryonic day 17 | Cre is expressed using promoter of oseocalcin. Increased bone formation with distorted bone architecture. Reduced survival to time of weaning (10%). | [119] |

| ApcCKO allele; Expression of Cre recombinase results in excision of Apc exon 14 and a stop codon at a.a. 580 | [93] | |||

| Mouse | Organ |

Developmental stage |

Cre delivery/phenotype | Ref |

| ApcCKO/CKO-LSL-Kras | Distal colon | Adult | Cre is delivered via adenovirus vector injected in the colon through the anus, resulting in excision of Apc exon 14 and expression of mutant constitutively active Kras. Adenocarcinoma in the distal colon that show spontaneous metastasis to the liver after 24 weeks |

[120] |

|

K14-Cre-ApcCKO/CKO K14-Cre-ApcCKO/+ |

Ectodermal derived tissues including mammary glands | Day 9.5 embryonic | Cre is expressed using Keratin-14 promoter in epidermal tissues. Growth retardation, premature death, abnormalities in epidermal derived tissues including: hair follicles, cornea, and teeth. Thymus hypoplasia, squamous metaplasia in the thymus (homozygous), mammary tumors in 76.5% of heterozygous females. | [93, 121] |

|

WAP-Cre-ApcCKO/CKO WAP-Cre-ApcCKO/+ |

Lactating epithelial cells | Lactation | Cre is expressed using Whey Acidic Protein (Wap) promoter. Mammary tumors in nulliparous and multiparous females (less than 20%) | [93] |

| Ahmr2-Cre-Apcflox/flox | Uterine stroma (in females) Sertoli cells (in males) | Fetus | Cre is expressed using anti-Mullerian hormone type II receptor promoter in mesenchyme of fetal Mullerian duct. Progressive uterine hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma. Apc has a cell-non-autonomous role as an endometrial tumor suppressor protein. Large spleens (in females); abnormal spermatogenesis, loss of the apical part of Sertoli cells, disruption of tight junctions, no tumors (in males). | [43, 130] |

| Pms2-ApcCKO/+ | ?? | Out-of-frame Cre that reverts back in-frame stochastically. Rate of transformation is higher in Apc1638N/CKO and ApcMin/CKO mice relative to ApcCKO/+ mice | [118] | |

| Apc15flox allele; Expression of Cre recombinase results in excision of Apc last exon and 3’UTR region | [96] | |||

| Mouse | Organ |

Developmental stage |

Cre delivery/phenotype | Ref |

| FabplCre; Apc15lox/+ | Distal small intestine and large intestine | ?? | Cre is expressed using fatty-acid binding protein-1 (Fabp1) promoter in some cells. Develop adenoma and adenocarcinoma mainly in large intestine | [96] |

| Ahmr2-Cre-Apc15flox/15flox | Uterine myometrium | ?? | Cre is expressed using anti-Mullerian hormone type II receptor promoter in mesenchyme of fetal Mullerian duct. Myometrial defects, dystocia, reduced number of endometrial glands | [131] |

| Pgr-Cre-Apcflox/flox | Uterine endometrium& myometrium | ?? | Cre is expressed using progesterone receptor promoter. Myometrial and endometrial defects, endometriosis interna-like changes | [131] |

| Math1-Cre-ApcFl/Fl | Cerebellum | Day 12.5 embryonic | Cre is expressed using Math-1 promoter in Granule cells in the cerebellum. No tumor. Cerebellar cortical hypoplasia, impaired motor coordinator and ataxia | [122] |

| Col2a1-Cre-Apc15lox/15lox | Mesenchymal cells | Day 9.5 embryonic in sclerotome Day 12.5–16.5 embryonic in chondrogenic and osteogenic cells. | Cre is expressed using Col2a1 (collagen-2a-1) promoter in mesenchymal cells. Embryonic lethal, defective cartilage and bone differentiation | [124] |

| Apc15lox/15lox Apc15lox/1638N Apc15lox/+ Apc15lox/1572T | Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells | Adult |

Cre delivered by a lentiviral vector ex-vivo Different levels of Wnt signaling activation associated with differential effects on hematopoietic stem cell and myeloid and lymphoid differentiation |

[123] |

| ApcΔex14 allele; Expression of Cre recombinase results in excision of Apc exon 14 and a stop codon at a.a. 580 | [95] | |||

| Mouse | Organ |

Developmental stage |

Cre delivery/phenotype | Ref |

| Vil-CreERT2-Apclox/lox | Small and large intestine | Adult | Cre expressed using Villin promoter when the mice are injected with Tamoxifen. Upregulation of Wnt signaling, increased proliferation and apoptosis, decreased migration, increased number of cells committed to Paneth cell differentiation. | [116] |

| ApcΔex14/Δex14 | Liver | Adult | Cre driven by a CMV promoter is delivered using Adenovirus injected intravenously. High viral dose causes hepatomegaly, hepatocellular hyperplasia and death. Low viral dose causes hepatocellular carcinoma |

[95] |

| Ap/lox468 allele; Expression of Cre recombinase results in Excision of exons 11 & 12 and a frameshift splicing exons 10–13 and truncating Apc at codon 468. | [113] | |||

| Mouse | Organ |

Developmental stage |

Cre delivery/phenotype | Ref |

| Ts4Cre-Apclox468/+ | Colon and distal ileum | ?? | Cre is expressed using Ts4 promoter. Polyposis in the colon and distal ileum. Lipoteichoic acid-deficient lactobacilli bacteria modulate colonic inflammation and reduce polyp formation. | [114] |

| LckCre-Apclox/lox468 | Thymus | Starts at CD44− CD25+ double-negative 3 (DN3) stage and complete by DN4 stage of lymphocyte development | Cre is expressed using Lck promoter during the development of thymocytes. Thymic atrophy, reduced T-lymphocyte receptor rearrangement, increasing proliferation of pre-T cells, chromosomal segregation defects, T-cell developmental delay. | [113] |

not defined

Apc rat models

A rat model with a germline nonsense mutation at Apc codon 1137 (Apcam1137) was generated to overcome some of the limitations of Apc mouse models [134]. Rats homozygous for the Apcam1137 allele die as embryos. Apcam1137/+ rats develop both small intestinal and colonic polyps with 100% penetrance, and are called “PIRC” rats for Polyposis In Rat Colons [134]. The polyps in PIRC rats are adenomas with malignant changes and local invasion seen in old rats. No signs of metastasis have been detected in these rats. As seen in humans with germline Apc mutations, the polyps from PIRC rats show β-catenin nuclear translocation in advanced but not in early adenomas. As with ApcMin/+ mice, most intestinal polyps in PIRC rats show LOH. Because chromosome 18, which carries the Apc gene in rats, is metacentric, pyrosequencing could be used to demonstrate that LOH in PIRC rats predominantly occurs by means of homologous recombination [134]. The greater width of rat intestines and colons, relative to those of mice, allows for growth of larger intestinal tumors, which facilitates study of tumor progression beyond the early stage. Wider colons and higher colonic tumor multiplicities in rats also supported a longitudinal endoscopic study of tumorigenesis [134]. Male PIRC rats have more polyps than do females [101]. Most Apc mouse models do not show a gender bias. However, in ApcMin-FCCC/+ mice, an ApcMin/+ mouse model with a different genetic background, males also develop more colonic polyps than do females [135]. In contrast, female ApcΔe1–15/+ mice display more severe phenotypes than do males [101]. In humans, women appear to be slightly less affected by colon cancer than are men [136]. PIRC rats also show high incidence of jaw tumors, which are the main cause of morbidity in female PIRC rats [134]. This extra-intestinal phenotype has also been described in patients with FAP syndrome [137].

A second Apc rat model (Kyoto Apc Delta or KAD rat) was developed with a germline nonsense mutation in the Apc gene, resulting in deletion of the C-terminal 321 amino acids [138]. This deletion does not appear to affect life expectancy even in homozygous KAD rats, and no spontaneous polyps develop in the KAD rat intestines. However, KAD rats showed enhanced inflammation-mediated colon tumorigenicity, consistent with a Wnt-independent role for the C-terminal domain of Apc in tumor suppression.

In summary, rodent models with Apc mutations were first generated more than 2 decades ago. Studies of 45 rodent models with germline and conditional Apc mutations have led to greater understanding of the role of APC in development, differentiation, and homeostasis of intestinal epithelial cells. In addition, these models have allowed exploration of the role of APC in intestinal and extra-intestinal development and tumorigenesis. Mouse and rat models with germline Apc mutations have permitted experimental testing of different molecular pathways and investigation of genetic and environmental contributions to tumor formation, not only in the gastrointestinal tract but also in other tissues. These models have also facilitated testing different preventive and therapeutic agents in preclinical studies. Continued effort should be made to clarify some of the less understood features of the different Apc rodent models. These lingering mysteries include identifying the variables that contribute to differences in extra-intestinal phenotypes, and polyp distribution and number. The full potential of the Apc models has not yet been reached; it is expected that they will continue to provide insight into Apc and cancer biology for decades to come.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Joslyn G, Carlson M, Thliveris A, Albertsen H, Gelbert L, Samowitz W, Groden J, Stevens J, Spirio L, Robertson M, Sargeant L, Krapcho K, Wolff E, Burt R, Hughes JP, Warrington J, McPherson J, Wasmuth J, Paslier DL, Abderrahim H, Cohen D, Leppert M, White R. Identification of deletion mutations and three new genes at the familial polyposis locus. Cell. 1991;66:601–613. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Groden J, Thliveris A, Samowitz W, Carlson M, Gelbert L, Albertsen H, Joslyn G, Stevens J, Spirio L, Robertson M, Sargeant L, Krapcho K, Wolff E, Burt R, Hughes JP, Warrington J, McPherson J, Wasmuth J, Paslier DL, Abderrahim H, Cohen D, Leppert M, White R. Identification and characterization of the familial adenomatous polyposis coli gene. Cell. 1991;66:589–600. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishisho I, Nakamura Y, Miyoshi Y, Miki Y, Ando H, Horii A, Koyama K, Utsunomiya J, Baba S, Hedge P. Mutations of chromosome 5q21 genes in FAP and colorectal cancer patients. Science. 1991;253:665–669. doi: 10.1126/science.1651563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinzler KW, Nilbert MC, Su LK, Vogelstein B, Bryan TM, Levy DB, Smith KJ, Preisinger AC, Hedge P, McKechnie D, Finniear R, Markham A, Groffen J, Boguski MS, Altschul SF, Horii A, Ando H, Miyoshi Y, Miki Y, Nishisho I, Nakamura Y. Identification of FAP locus genes from chromosome 5q21. Science. 1991;253:661–665. doi: 10.1126/science.1651562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell. 1996;87:159–170. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81333-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.TCGA. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487:330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polakis P. Wnt signaling and cancer. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1837–1851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Senda T, Iizuka-Kogo A, Onouchi T, Shimomura A. Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) plays multiple roles in the intestinal and colorectal epithelia. Medical molecular morphology. 2007;40:68–81. doi: 10.1007/s00795-006-0352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minde DP, Anvarian Z, Rudiger SG, Maurice MM. Messing up disorder: How do missense mutations in the tumor suppressor protein APC lead to cancer? Mol Cancer. 2011;10:101. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carbone L. What Animals Want : Expertise and Advocacy in Laboratory Animal Welfare Policy. Cary, NC, USA: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uronis JM, Threadgill DW. Murine models of colorectal cancer. Mamm Genome. 2009;20:261–268. doi: 10.1007/s00335-009-9186-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su LK, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Preisinger AC, Moser AR, Luongo C, Gould KA, Dove WF. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science. 1992;256:668–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1350108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gaspar C, Cardoso J, Franken P, Molenaar L, Morreau H, Moslein G, Sampson J, Boer JM, de Menezes RX, Fodde R. Cross-species comparison of human and mouse intestinal polyps reveals conserved mechanisms in adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)-driven tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1363–1380. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moser A, Pitot H, Dove W. A dominant mutation that predisposes to multiple intestinal neoplasia in the mouse. Science. 1990;247:322–324. doi: 10.1126/science.2296722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su L-K, Kinzler K, Vogelstein B, Preisinger A, Moser A, Luongo C, Gould K, Dove W. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science. 1992;256:668–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1350108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moser AR, Dove WF, Roth KA, Gordon JI. The Min (multiple intestinal neoplasia) mutation: its effect on gut epithelial cell differentiation and interaction with a modifier system. J Cell Biol. 1992;116:1517–1526. doi: 10.1083/jcb.116.6.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moser AR, Pitot HC, Dove WF. A dominant mutation that predisposes to multiple intestinal neoplasia in the mouse. Science. 1990;247:322–324. doi: 10.1126/science.2296722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moser AR, Mattes EM, Dove WF, Lindstrom MJ, Haag JD, Gould MN. ApcMin, a mutation in the murine Apc gene, predisposes to mammary carcinomas and focal alveolar hyperplasias. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8977–8981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCart AE, Vickaryous NK, Silver A. Apc mice: models, modifiers and mutants. Pathol Res Pract. 2008;204:479–490. doi: 10.1016/j.prp.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shoemaker AR, Moser AR, Midgley CA, Clipson L, Newton MA, Dove WF. A resistant genetic background leading to incomplete penetrance of intestinal neoplasia and reduced loss of heterozygosity in ApcMin/+ mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10826–10831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen X, Halberg RB, Burch RP, Dove WF. Intestinal adenomagenesis involves core molecular signatures of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Journal of molecular histology. 2008;39:283–294. doi: 10.1007/s10735-008-9164-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halberg RB, Waggoner J, Rasmussen K, White A, Clipson L, Prunuske AJ, Bacher JW, Sullivan R, Washington MK, Pitot HC, Petrini JH, Albertson DG, Dove WF. Long-lived Min mice develop advanced intestinal cancers through a genetically conservative pathway. Cancer Res. 2009;69:5768–5775. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luongo C, Moser AR, Gledhill S, Dove WF. Loss of Apc+ in intestinal adenomas from Min mice. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5947–5952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Millar CB, Guy J, Sansom OJ, Selfridge J, MacDougall E, Hendrich B, Keightley PD, Bishop SM, Clarke AR, Bird A. Enhanced CpG mutability and tumorigenesis in MBD4-deficient mice. Science. 2002;297:403–405. doi: 10.1126/science.1073354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakayama T, Yamazumi K, Uemura T, Yoshizaki A, Yakata Y, Matsuu-Matsuyama M, Shichijo K, Sekine I. X radiation up-regulates the occurrence and the multiplicity of invasive carcinomas in the intestinal tract of Apc(min/+) mice. Radiat Res. 2007;168:433–439. doi: 10.1667/RR0869.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sieber OM, Howarth KM, Thirlwell C, Rowan A, Mandir N, Goodlad RA, Gilkar A, Spencer-Dene B, Stamp G, Johnson V, Silver A, Yang H, Miller JH, Ilyas M, Tomlinson IP. Myh deficiency enhances intestinal tumorigenesis in multiple intestinal neoplasia (ApcMin/+) mice. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8876–8881. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reichling T, Goss KH, Carson DJ, Holdcraft RW, Ley-Ebert C, Witte D, Aronow BJ, Groden J. Transcriptional profiles of intestinal tumors in Apc(Min) mice are unique from those of embryonic intestine and identify novel gene targets dysregulated in human colorectal tumors. Cancer Res. 2005;65:166–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Will OC, Leedham SJ, Elia G, Phillips RKS, Clark SK, Tomlinson IPM. Location in the large bowel influences the APC mutations observed in FAP adenomas Familial cancer. 2010;9:389–393. doi: 10.1007/s10689-010-9332-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haigis KM, Caya JG, Reichelderfer M, Dove WF. Intestinal adenomas can develop with a stable karyotype and stable microsatellites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8927–8931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132275099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baran AA, Silverman KA, Zeskand J, Koratkar R, Palmer A, McCullen K, Curran WJ, Jr, Edmonston TB, Siracusa LD, Buchberg AM. The modifier of Min 2 (Mom2) locus: embryonic lethality of a mutation in the Atp5a1 gene suggests a novel mechanism of polyp suppression. Genome Res. 2007;17:566–576. doi: 10.1101/gr.6089707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Imaoka T, Okamoto M, Nishimura M, Nishimura Y, Ootawara M, Kakinuma S, Tokairin Y, Shimada Y. Mammary tumorigenesis in ApcMin/+ mice is enhanced by X irradiation with a characteristic age dependence. Radiat Res. 2006;165:165–173. doi: 10.1667/rr3502.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Imbert A, Eelkema R, Jordan S, Feiner H, Cowin P. Delta N89 beta-catenin induces precocious development, differentiation, and neoplasia in mammary gland. J Cell Biol. 2001;153:555–568. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.3.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michaelson JS, Leder P. beta-catenin is a downstream effector of Wnt-mediated tumorigenesis in the mammary gland. Oncogene. 2001;20:5093–5099. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Half E, Bercovich D, Rozen P. Familial adenomatous polyposis. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2009;4:22. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-4-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jin Z, Tamura G, Tsuchiya T, Sakata K, Kashiwaba M, Osakabe M, Motoyama T. Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene promoter hypermethylation in primary breast cancers. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:69–73. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sarrio D, Moreno-Bueno G, Hardisson D, Sanchez-Estevez C, Guo M, Herman JG, Gamallo C, Esteller M, Palacios J. Epigenetic and genetic alterations of APC and CDH1 genes in lobular breast cancer: relationships with abnormal E-cadherin and catenin expression and microsatellite instability. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:208–215. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Furuuchi K, Tada M, Yamada H, Kataoka A, Furuuchi N, Hamada J, Takahashi M, Todo S, Moriuchi T. Somatic mutations of the APC gene in primary breast cancers. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:1997–2005. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65072-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Prasad CP, Mirza S, Sharma G, Prashad R, DattaGupta S, Rath G, Ralhan R. Epigenetic alterations of CDH1 and APC genes: Relationship with activation of Wnt/Î2-catenin Pathway in invasive ductal carcinoma of breast. Life sciences. 2008;83:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.You S, Ohmori M, Pena MM, Nassri B, Quiton J, Al-Assad ZA, Liu L, Wood PA, Berger SH, Liu Z, Wyatt MD, Price RL, Berger FG, Hrushesky WJ. Developmental abnormalities in multiple proliferative tissues of Apc(Min/+) mice. International journal of experimental pathology. 2006;87:227–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2006.00477.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chae WJ, Gibson TF, Zelterman D, Hao L, Henegariu O, Bothwell AL. Ablation of IL-17A abrogates progression of spontaneous intestinal tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:5540–5544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912675107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lane SW, Sykes SM, Al-Shahrour F, Shterental S, Paktinat M, Lo Celso C, Jesneck JL, Ebert BL, Williams DA, Gilliland DG. The Apc(min) mouse has altered hematopoietic stem cell function and provides a model for MPD/MDS. Blood. 2010;115:3489–3497. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-251728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coletta PL, Muller AM, Jones EA, Muhl B, Holwell S, Clarke D, Meade JL, Cook GP, Hawcroft G, Ponchel F, Lam WK, MacLennan KA, Hull MA, Bonifer C, Markham AF. Lymphodepletion in the ApcMin/+ mouse model of intestinal tumorigenesis. Blood. 2004;103:1050–1058. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-03-0707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanwar PS, Zhang L, Teixeira JM. Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) is essential for maintaining the integrity of the seminiferous epithelium. Mol Endocrinol. 2011;25:1725–1739. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prosperi JR, Becher KR, Willson TA, Collins MH, Witte DP, Goss KH. The APC tumor suppressor is required for epithelial integrity in the mouse mammary gland. Journal of cellular physiology. 2009;220:319–331. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lefebvre AM, Chen I, Desreumaux P, Najib J, Fruchart JC, Geboes K, Briggs M, Heyman R, Auwerx J. Activation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma promotes the development of colon tumors in C57BL/6J-APCMin/+ mice. Nature medicine. 1998;4:1053–1057. doi: 10.1038/2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Girnun GD, Smith WM, Drori S, Sarraf P, Mueller E, Eng C, Nambiar P, Rosenberg DW, Bronson RT, Edelmann W, Kucherlapati R, Gonzalez FJ, Spiegelman BM. APC-dependent suppression of colon carcinogenesis by PPARgamma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13771–13776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162480299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saez E, Tontonoz P, Nelson MC, Alvarez JG, Ming UT, Baird SM, Thomazy VA, Evans RM. Activators of the nuclear receptor PPARgamma enhance colon polyp formation. Nature medicine. 1998;4:1058–1061. doi: 10.1038/2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niho N, Mutoh M, Komiya M, Ohta T, Sugimura T, Wakabayashi K. Improvement of hyperlipidemia by indomethacin in Min mice. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:1665–1669. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dove WF, Cormier RT, Gould KA, Halberg RB, Merritt AJ, Newton MA, Shoemaker AR. The intestinal epithelium and its neoplasms: genetic, cellular and tissue interactions. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 1998;353:915–923. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwong LN, Dove WF. APC and its modifiers in colon cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;656:85–106. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1145-2_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Silverman KA, Koratkar R, Siracusa LD, Buchberg AM. Identification of the modifier of Min 2 (Mom2) locus, a new mutation that influences Apc-induced intestinal neoplasia. Genome Res. 2002;12:88–97. doi: 10.1101/gr.206002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kwong LN, Shedlovsky A, Biehl BS, Clipson L, Pasch CA, Dove WF. Identification of Mom7, a novel modifier of Apc(Min/+) on mouse chromosome 18. Genetics. 2007;176:1237–1244. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.071217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suraweera N, Haines J, McCart A, Rogers P, Latchford A, Coster M, Polanco-Echeverry G, Guenther T, Wang J, Sieber O, Tomlinson I, Silver A. Genetic determinants modulate susceptibility to pregnancy-associated tumourigenesis in a recombinant line of Min mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:3429–3435. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crist RC, Roth JJ, Lisanti MP, Siracusa LD, Buchberg AM. Identification of Mom12 and Mom13, two novel modifier loci of Apc (Min)-mediated intestinal tumorigenesis. Cell Cycle. 2011;10:1092–1099. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.7.15089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacPhee M, Chepenik KP, Liddell RA, Nelson KK, Siracusa LD, Buchberg AM. The secretory phospholipase A2 gene is a candidate for the Mom1 locus, a major modifier of ApcMin-induced intestinal neoplasia. Cell. 1995;81:957–966. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cormier RT, Hong KH, Halberg RB, Hawkins TL, Richardson P, Mulherkar R, Dove WF, Lander ES. Secretory phospholipase Pla2g2a confers resistance to intestinal tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 1997;17:88–91. doi: 10.1038/ng0997-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harris ES, Nelson WJ. Adenomatous polyposis coli regulates endothelial cell migration independent of roles in beta-catenin signaling and cell-cell adhesion. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:2611–2623. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-03-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Munemitsu S, Souza B, Muller O, Albert I, Rubinfeld B, Polakis P. The APC gene product associates with microtubules in vivo and promotes their assembly in vitro. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3676–3681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Radulescu S, Ridgway RA, Appleton P, Kroboth K, Patel S, Woodgett J, Taylor S, Nathke IS, Sansom OJ. Defining the role of APC in the mitotic spindle checkpoint in vivo: APCdeficient cells are resistant to Taxol. Oncogene. 2010 doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fodde R, Kuipers J, Rosenberg C, Smits R, Kielman M, Gaspar C, van Es JH, Breukel C, Wiegant J, Giles RH, Clevers H. Mutations in the APC tumour suppressor gene cause chromosomal instability. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:433–438. doi: 10.1038/35070129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Green RA, Kaplan KB. Chromosome instability in colorectal tumor cells is associated with defects in microtubule plus-end attachments caused by a dominant mutation in APC. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:949–961. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instabilities in human cancers. Nature. 1998;396:643–649. doi: 10.1038/25292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kucherlapati M, Nguyen A, Kuraguchi M, Yang K, Fan K, Bronson R, Wei K, Lipkin M, Edelmann W, Kucherlapati R. Tumor progression in Apc(1638N) mice with Exo1 and Fen1 deficiencies. Oncogene. 2007;26:6297–6306. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bi X, Pohl NM, Yin Z, Yang W. Loss of JNK2 increases intestinal tumor susceptibility in Apc1638+/− mice with dietary modulation. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:584–588. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nandan MO, Ghaleb AM, McConnell BB, Patel NV, Robine S, Yang VW. Kruppellike factor 5 is a crucial mediator of intestinal tumorigenesis in mice harboring combined ApcMin and KRASV12 mutations. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:63. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wilson AJ, Byun DS, Popova N, Murray LB, L'Italien K, Sowa Y, Arango D, Velcich A, Augenlicht LH, Mariadason JM. Histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) and other class I HDACs regulate colon cell maturation and p21 expression and are deregulated in human colon cancer. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13548–13558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510023200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Edelmann W, Yang K, Kuraguchi M, Heyer J, Lia M, Kneitz B, Fan K, Brown AM, Lipkin M, Kucherlapati R. Tumorigenesis in Mlh1 and Mlh1/Apc1638N mutant mice. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1301–1307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smits R, Kartheuser A, Jagmohan-Changur S, Leblanc V, Breukel C, de Vries A, van Kranen H, van Krieken JH, Williamson S, Edelmann W, Kucherlapati R, KhanPm, Fodde R. Loss of Apc and the entire chromosome 18 but absence of mutations at the Ras and Tp53 genes in intestinal tumors from Apc1638N, a mouse model for Apc-driven carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 1997;18:321–327. doi: 10.1093/carcin/18.2.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Haigis KM, Hoff PD, White A, Shoemaker AR, Halberg RB, Dove WF. Tumor regionality in the mouse intestine reflects the mechanism of loss of Apc function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9769–9773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403338101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smits R, van der Houven van Oordt W, Luz A, Zurcher C, Jagmohan-Changur S, Breukel C, Khan PM, Fodde R. Apc1638N: a mouse model for familial adenomatous polyposisassociated desmoid tumors and cutaneous cysts. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:275–283. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70478-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lyons LA, Lewis RA, Strong LC, Zuckerbrod S, Ferrell RE. A genetic study of Gardner syndrome and congenital hypertrophy of the retinal pigment epithelium. American journal of human genetics. 1988;42:290–296. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nieuwenhuis MH, Vasen HF. Correlations between mutation site in APC and phenotype of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): a review of the literature. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2007;61:153–161. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bisgaard ML, Bulow S. Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP): genotype correlation to FAP phenotype with osteomas and sebaceous cysts. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2006;140:200–204. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Crabtree M, Sieber OM, Lipton L, Hodgson SV, Lamlum H, Thomas HJW, Neale K, Phillips RKS, Heinimann K, Tomlinson IPM. Refining the relation between 'first hits' and 'second hits' at the APC locus: the 'loose fit' model and evidence for differences in somatic mutation spectra among patients. Oncogene. 2003;22:4257–4265. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fodde R, Edelmann W, Yang K, van Leeuwen C, Carlson C, Renault B, Breukel C, Alt E, Lipkin M, Khan PM, Kucherlapati R. A targeted chain-termination mutation in the mouse Apc gene results in multiple intestinal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:8969–8973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Smits R, Kielman MF, Breukel C, Zurcher C, Neufeld K, Jagmohan-Changur S, Hofland N, van Dijk J, White R, Edelmann W, Kucherlapati R, Khan PM, Fodde R. Apc1638T: a mouse model delineating critical domains of the adenomatous polyposis coli protein involved in tumorigenesis and development. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1309–1321. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yokoyama A, Nomura R, Kurosumi M, Shimomura A, Onouchi T, Iizuka-Kogo A, Smits R, Oda N, Fodde R, Itoh M, Senda T. The C-terminal domain of the adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc) protein is involved in thyroid morphogenesis and function. Medical molecular morphology. 2011;44:207–212. doi: 10.1007/s00795-010-0529-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gaspar C, Franken P, Molenaar L, Breukel C, van der Valk M, Smits R, Fodde R. A targeted constitutive mutation in the APC tumor suppressor gene underlies mammary but not intestinal tumorigenesis. PLoS genetics. 2009;5:e1000547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Falk S, Wurdak H, Ittner LM, Ille F, Sumara G, Schmid MT, Draganova K, Lang KS, Paratore C, Leveen P, Suter U, Karlsson S, Born W, Ricci R, Gotz M, Sommer L. Brain area-specific effect of TGF-beta signaling on Wnt-dependent neural stem cell expansion. Cell stem cell. 2008;2:472–483. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alberici P, Jagmohan-Changur S, De Pater E, Van Der Valk M, Smits R, Hohenstein P, Fodde R. Smad4 haploinsufficiency in mouse models for intestinal cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:1841–1851. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lamlum H, Ilyas M, Rowan A, Clark S, Johnson V, Bell J, Frayling I, Efstathiou J, Pack K, Payne S, Roylance R, Gorman P, Sheer D, Neale K, Phillips R, Talbot I, Bodmer W, Tomlinson I. The type of somatic mutation at APC in familial adenomatous polyposis is determined by the site of the germline mutation: a new facet to Knudson's 'two-hit' hypothesis. Nature medicine. 1999;5:1071–1075. doi: 10.1038/12511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Albuquerque C, Breukel C, van der Luijt R, Fidalgo P, Lage P, Slors FJ, Leitao CN, Fodde R, Smits R. The 'just-right' signaling model: APC somatic mutations are selected based on a specific level of activation of the beta-catenin signaling cascade. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1549–1560. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lamlum H, Papadopoulou A, Ilyas M, Rowan A, Gillet C, Hanby A, Talbot I, Bodmer W, Tomlinson I. APC mutations are sufficient for the growth of early colorectal adenomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:2225–2228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040564697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pollard P, Deheragoda M, Segditsas S, Lewis A, Rowan A, Howarth K, Willis L, Nye E, McCart A, Mandir N, Silver A, Goodlad R, Stamp G, Cockman M, East P, Spencer-Dene B, Poulsom R, Wright N, Tomlinson I. The Apc 1322T mouse develops severe polyposis associated with submaximal nuclear beta-catenin expression. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2204–2213. e2201–e2213. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Quesada CF, Kimata H, Mori M, Nishimura M, Tsuneyoshi T, Baba S. Piroxicam and acarbose as chemopreventive agents for spontaneous intestinal adenomas in APC gene 1309 knockout mice. Japanese journal of cancer research : Gann. 1998;89:392–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1998.tb00576.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lewis A, Segditsas S, Deheragoda M, Pollard P, Jeffery R, Nye E, Lockstone H, Davis H, Clark S, Stamp G, Poulsom R, Wright N, Tomlinson I. Severe polyposis in Apc(1322T) mice is associated with submaximal Wnt signalling and increased expression of the stem cell marker Lgr5. Gut. 2010;59:1680–1686. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.193680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Niho N, Takahashi M, Kitamura T, Shoji Y, Itoh M, Noda T, Sugimura T, Wakabayashi K. Concomitant suppression of hyperlipidemia and intestinal polyp formation in Apc-deficient mice by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor ligands. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6090–6095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Crist RC, Roth JJ, Baran AA, McEntee BJ, Siracusa LD, Buchberg AM. The armadillo repeat domain of Apc suppresses intestinal tumorigenesis. Mamm Genome. 2010;21:450–457. doi: 10.1007/s00335-010-9288-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sasai H, Masaki M, Wakitani K. Suppression of polypogenesis in a new mouse strain with a truncated Apc(Delta474) by a novel COX-2 inhibitor, JTE-522. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:953–958. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Oshima M, Oshima H, Kobayashi M, Tsutsumi M, Taketo MM. Evidence against dominant negative mechanisms of intestinal polyp formation by Apc gene mutations. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2719–2722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Oshima M, Oshima H, Kitagawa K, Kobayashi M, Itakura C, Taketo M. Loss of Apc heterozygosity and abnormal tissue building in nascent intestinal polyps in mice carrying a truncated Apc gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4482–4486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Oshima H, Oshima M, Kobayashi M, Tsutsumi M, Taketo MM. Morphological and molecular processes of polyp formation in Apc(delta716) knockout mice. Cancer Res. 1997;57:1644–1649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kuraguchi M, Wang XP, Bronson RT, Rothenberg R, Ohene-Baah NY, Lund JJ, Kucherlapati M, Maas RL, Kucherlapati R. Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) is required for normal development of skin and thymus. PLoS genetics. 2006;2:e146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shibata H, Toyama K, Shioya H, Ito M, Hirota M, Hasegawa S, Matsumoto H, Takano H, Akiyama T, Toyoshima K, Kanamaru R, Kanegae Y, Saito I, Nakamura Y, Shiba K, Noda T. Rapid colorectal adenoma formation initiated by conditional targeting of the Apc gene. Science. 1997;278:120–123. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Colnot S, Decaens T, Niwa-Kawakita M, Godard C, Hamard G, Kahn A, Giovannini M, Perret C. Liver-targeted disruption of Apc in mice activates beta-catenin signaling and leads to hepatocellular carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:17216–17221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404761101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Robanus-Maandag EC, Koelink PJ, Breukel C, Salvatori DC, Jagmohan-Changur SC, Bosch CA, Verspaget HW, Devilee P, Fodde R, Smits R. A new conditional Apc-mutant mouse model for colorectal cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:946–952. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Colnot S, Niwa-Kawakita M, Hamard G, Godard C, Le Plenier S, Houbron C, Romagnolo B, Berrebi D, Giovannini M, Perret C. Colorectal cancers in a new mouse model of familial adenomatous polyposis: influence of genetic and environmental modifiers. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 2004;84:1619–1630. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Taketo MM, Edelmann W. Mouse models of colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:780–798. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Herrera L, Kakati S, Gibas L, Pietrzak E, Sandberg AA. Gardner syndrome in a man with an interstitial deletion of 5q. Am J Med Genet. 1986;25:473–476. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320250309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Sieber OM, Lamlum H, Crabtree MD, Rowan AJ, Barclay E, Lipton L, Hodgson S, Thomas HJ, Neale K, Phillips RK, Farrington SM, Dunlop MG, Mueller HJ, Bisgaard ML, Bulow S, Fidalgo P, Albuquerque C, Scarano MI, Bodmer W, Tomlinson IP, Heinimann K. Whole-gene APC deletions cause classical familial adenomatous polyposis, but not attenuated polyposis or "multiple" colorectal adenomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:2954–2958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.042699199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cheung AF, Carter AM, Kostova KK, Woodruff JF, Crowley D, Bronson RT, Haigis KM, Jacks T. Complete deletion of Apc results in severe polyposis in mice. Oncogene. 2009 doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Neufeld KL. Nuclear APC. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;656:13–29. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1145-2_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Henderson BR. Nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of APC regulates beta-catenin subcellular localization and turnover. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:653–660. doi: 10.1038/35023605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang Y, Azuma Y, Moore D, Osheroff N, Neufeld KL. Interaction between Tumor Suppressor Adenomatous Polyposis Coli and Topoisomerase II{alpha}: Implication for the G2/M Transition. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:4076–4085. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jaiswal AS, Narayan S. A novel function of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) in regulating DNA repair. Cancer Lett. 2008;271:272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Narayan S, Jaiswal AS. Activation of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene expression by the DNA-alkylating agent N-methyl-N'-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine requires p53. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30619–30622. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zeineldin M, Cunningham J, McGuinness W, Alltizer P, Cowley B, Blanchat B, Xu W, Pinson D, Neufeld KL. A knock-in mouse model reveals roles for nuclear Apc in cell proliferation, Wnt signal inhibition and tumor suppression. Oncogene. 2011 doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lewis A, Davis H, Deheragoda M, Pollard P, Nye E, Jeffery R, Segditsas S, East P, Poulsom R, Stamp G, Wright N, Tomlinson I. The C-terminus of Apc does not influence intestinal adenoma development or progression. J Pathol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/path.2972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Li Q, Ishikawa TO, Oshima M, Taketo MM. The threshold level of adenomatous polyposis coli protein for mouse intestinal tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8622–8627. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ishikawa TO, Tamai Y, Li Q, Oshima M, Taketo MM. Requirement for tumor suppressor Apc in the morphogenesis of anterior and ventral mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 2003;253:230–246. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Su LK, Johnson KA, Smith KJ, Hill DE, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Association between wild type and mutant APC gene products. Cancer Res. 1993;53:2728–2731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sansom O. Tissue-specific tumour suppression by APC. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;656:107–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gounari F, Chang R, Cowan J, Guo Z, Dose M, Gounaris E, Khazaie K. Loss of adenomatous polyposis coli gene function disrupts thymic development. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:800–809. doi: 10.1038/ni1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Khazaie K, Zadeh M, Khan MW, Bere P, Gounari F, Dennis K, Blatner NR, Owen JL, Klaenhammer TR, Mohamadzadeh M. Abating colon cancer polyposis by Lactobacillus acidophilus deficient in lipoteichoic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:10462–10467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207230109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]