Abstract

Objective

Mediational intervention for sensitizing caregivers (MISC) is a structured program enabling caregivers to enhance their child’s cognitive and emotional development through daily interactions. The principal aim was to evaluate if a year-long MISC caregiver training program produced greater improvement in child cognitive and emotional development compared with a control program.

Methods

119 uninfected HIV-exposed preschool children and their caregivers were randomly assigned to one of two treatment arms: biweekly MISC training alternating between home and clinic for one year or a health and nutrition curriculum. All children were evaluated at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year with the Mullen Early Learning Scales, Color-Object Association Test (COAT) for memory, and Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) for psychiatric symptoms. Caregivers were evaluated on the same schedule with the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist (HSCL-25) for depression and anxiety.

Results

The treatment arms were compared using repeated-measures ANCOVA with child age, gender, weight, SES, caregiving quality, caregiver anxiety, and caregiver education as covariates. The MISC children had significantly greater gains compared to controls on the Mullen Receptive and Expressive Language development, and on the Mullen composite score of cognitive ability. COAT total memory for MISC children was marginally better than controls. No CBCL differences between the groups were noted. Caldwell HOME scores and observed mediational interaction scores from videotapes measuring caregiving quality also improved significantly more for the MISC group.

Conclusion

MISC enhanced cognitive performance, especially in language development. These benefits were possibly mediated by improved caregiving and positive emotional benefit to the caregiver.

Keywords: child development, HIV, caregiver, training, Uganda, language, cognition, nutrition

INTRODUCTION

Over 90% of pediatric HIV infections and AIDS deaths occur in Africa and more than 11 million children have lost at least one parent to AIDS.1 In Uganda, due to the AIDS epidemic, about 1 million children are orphans with one or both parents deceased and a new child is orphaned every 14 seconds.2 It is important to consider strategies for enhancing their cognitive and psychosocial development in the face of HIV disease, prenatal ART exposure and seriously compromised caregiving.3 When considering how to best address the global public health burden of the developmental effects of HIV on children, the African context is clearly paramount.

In rural areas of Sub-Sahara Africa, the family must rely upon labor-intensive subsistence agriculture to provide for the nutritional needs of the family. Because of this, maternal HIV disease and illness can severely disrupt not only the nurturing capacity of the mother for her children, but also food security for the entire family.4–6 Chronic nutritional hardship can severely undermine early childhood development.7, 8 Consequently, the AIDS epidemic can also have devastating consequences for non-infected children of HIV parent(s).

The Mediational Intervention for Sensitizing Caregivers (MISC) approach is a training program providing caregivers with strategies for enhancing the development of their children through day-to-day interactions in the home. The MISC approach was developed by Dr. Pnina Klein who documented the effectiveness of this approach with impoverished children in Africa and globally.9, 10 Unlike models based on simple direct learning through stimulating the senses with an enriched environment,9–11 MISC is a mediational approach based on Feurerstein’s theory of cognitive modifiability.12, 13

Feurerstein’s theory of structural cognitive modifiability emphasizes that human intelligence is best modified through guided (mediated) interactions that can intentionally shape a person’s cognitive processes to be more effective and adaptive. Such an approach can be especially strategic in helping low functioning children, as is the case with children at high risk from HIV in low-resource households and settings. This capacity for change is related to two types of human-environment interactions that are responsible for the development of differential cognitive functioning and higher mental processes: direct exposure to learning and mediated learning experience. We believe that this approach for enhancing cognition in at-risk HIV children is feasible in the rural African household.10

The primary study goal was to implement a MISC caregiver training intervention with the principal caregivers of HIV uninfected but exposed preschool-age children. Using a prospective intervention and control group cohort design, we hypothesized that a year-long biweekly MISC caregiver training program would significantly enhance the development of these children (motor, cognitive, psychosocial) compared to a health and nutrition control curriculum We aimed to establish the effectiveness of this home-based model for training parents/caregivers in practical skills for enriching the intellectual, social, and emotional developmental milieu of their HIV-affected children in a rural district area of eastern Uganda.

A secondary study aim was to evaluate the impact of the MISC intervention on the emotional well-being of the caregivers themselves. In Uganda, 53% of adults with HIV attending health care report high depressive symptoms which could compromise the quality of the caregiving interaction.14 We hypothesized that the caregivers receiving MISC training would have less depression compared to caregivers receiving a health/education nutrition curriculum (control intervention).

METHOD

Study recruitment population

IRB approval for this study was obtained from Michigan State University and Makerere University. Research permission was issued by the Ugandan National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST). Our study populations consisted of 120 uninfected children 2 to 4 yrs of age, born to HIV-infected mothers and their primary caregivers. The vast majority (> 90%) of the children in this study had the biological mother as the principal caregiver (Table 1). The remaining caregivers undergoing training were either the grandmother or aunt of the child. For both MISC and control groups, one-third of the caregivers were literate. Years of formal education ranged from 0 to 9 years, averaging just over 4 years of education across both groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline mean (M) and standard deviation (SD) measures at enrollment (baseline) with corresponding between-group difference P value for the two intervention groups: mediational intervention for sensitizing caregivers (MISC) training and the UCOBAC health/nutrition education curriculum (Control) intervention.

| MISC (N = 60) | Control (N = 59) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive Measures | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

|

| |||

| Child Age, yrs | 2.8 (0.35) | 2.8 (0.33) | 0.311 |

| Child Gender -male, n (%) | 32 (53.3) | 32 (54.2) | 0.922 |

| Primary Caregiver –biological mother, n (%) | 56 (93.3) | 53 (89.8) | 0.902 |

| Caregiver is Literate, n (%) | 20 (33.3) | 20 (33.9) | 0.992 |

| Caregiver Years of formal schooling | 4.2 (2.6) | 4.4 (2.6) | 0.64 |

| Child Weight, kgs | 12.4 (1.79) | 12.5 (1.64) | 0.92 |

| Child Height, cm | 90.8 (6.08) | 91.6 (6.22) | 0.65 |

| Child Mid-upper-arm circumference, cm | 16.4 (1.12) | 16.3 (1.19) | 0.31 |

| Child Weight-for-age Z# | −1.14 (1.45) | −1.00 (1.15) | 0.93 |

| Child Weight-for-Height Z# | −1.19 (1.55) | −1.24 (1.17) | 0.40 |

| Child Height-for-age Z# | −0.58 (1.66) | −0.34 (1.56) | 0.78 |

| Socio-economic status (material possessions) | 8.0 (2.19) | 7.9 (1.80) | 0.52 |

| Caldwell HOME total score | 16.2 (3.65) | 16.6 (3.20) | 0.91 |

| Gross Motor T scorea | 39.4 (9.70) | 37.1 (9.83) | 0.49 |

| Fine Motor T scorea | 40.1 (10.57) | 41.1 (11.16) | 0.65 |

| Visual Reception T scorea | 38.6 (10.95) | 39.6 (11.55) | 0.41 |

| Receptive Language T scorea | 44.5 (9.35) | 46.2 (9.64) | 0.79 |

| Expressive Language T scorea | 38.9 (10.71) | 41.2 (10.39) | 0.12 |

| MELS CompositeStandard scorea | 82.2 (13.98) | 85.1 (16.22) | 0.92 |

| COAT Immediate Memory raw scoreb | 4.5 (2.78) | 4.6 (3.03) | 0.16 |

| COAT Total Memory raw scoreb | 10.0 (7.43) | 11.4 (10.12) | 0.65 |

| CBCL Internalising problems T scorec | 62.8 (8.00) | 61.7 (11.38) | 0.78 |

| CBCL Externalising problems T scorec | 53.5 (8.14) | 53.0 (8.38) | 0.31 |

| CBCL Total Problems T scorec | 61.2 (8.40) | 61.4 (9.60) | 0.93 |

| HSCL-25 Depression raw scored | 15.2 (8.30) | 16.5 (8.01) | 0.65 |

| HSCL-25 Anxiety raw scored | 8.9 (5.46) | 10.3 (5.58) | 0.52 |

Using CDC 2000 norms (Epi Info)

Mullen Early Learning Scale (MELS) T values (adjusted for age and gender using American norms)

Color-Object Association Test (COAT)

Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) parent form for children 1.5 to 5 yrs T scores (adjusted for age and gender using Cross-Cultural norms)

Hopkins Symptoms Checklist 25-item (HSCL-25) scale for depression and anxiety

all P values are based on median test for two independent samples, unless otherwise noted.

P value based on Chi-square test for categorical relationships.

Participants were staying within a 20 km catchment area of Tororo town and were referred to our study by the Infectious Disease Research Collaboration (IDRC) at Tororo District Hospital. The IDRC supports research collaboration between Makerere University and the University of California – San Francisco. Our population of uninfected HIV-exposed children had previously been enrolled in an IDRC very early childhood malaria-treatment program. One caregiver-child dyad dropped out of the study following consent, leaving 119 total (n=59 MISC dyads; n=60 Control dyads).

The study children ranged from 2 to 4 years of age at enrollment (MISC: M = 2.8 yrs, SD = 0.35; Control: M = 2.8 yrs, SD = 0.33) and were nearly evenly split by gender (MISC: 53% male; Control: 54 % male) (Table 1). Biweekly hour-long training sessions with both groups of caregivers alternated between home (so MISC trainers could observe and direct caregiver/child interactions) and study office (where videotapes of interactions were used for the MISC caregivers).

Inclusion Criteria

Non-infected HIV-exposed children from the IDRC malaria treatment program, age 2 to 4 years. Caregiver must be willing and able to complete biweekly training program through the year.

Exclusion Criteria

A child was excluded from the study if they had a medical history of serious birth complications, severe malnutrition, bacterial meningitis, encephalitis, cerebral malaria, or other known brain injury or disorder requiring hospitalization which could overshadow the developmental benefits of MISC. A clinical officer used the Ten Question Questionnaire was used to screen for neurodisabilities.15, 16

Training of MISC Trainers

Prior to and during the study, our MISC consultants (CS, DG) did three week-long workshops with our Ugandan field team on how to train caregivers in the MISC program. The program director for the Uganda Community Based Organization for Child Welfare (UCOBAC; http://ucobac.org/cms/) trained a separate field team for the control-group caregivers in a health and nutrition educational program. UCOBAC had implemented this curriculum in 17 other rural Ugandan districts, through UNICEF support. Field trainers for both interventions were bachelor’s degree graduates from Makerere University either in Psychology or Social Work. Although fluent in Luganda, they were accompanied by translators from the area who spoke the local languages of Japhadola and Ateso. All the caregivers were fluent in one of these languages.

Learning the MISC approach is accomplished by training caregivers in mediational processes such as focusing (gaining the child’s attention and directing them to the learning experience in an engaging manner); exciting (communicating emotional excitement, appreciation, and affection with the learning experience); expanding (making the child aware of how that learning experience transcends the present situation and can include past and future needs and issues); encouraging (emotional support of the child to foster a sense of security and competence); and regulating (helping direct and shape the child’s behavior in constructive ways with a goal towards self-regulation). Most of the MISC training of caregivers is devoted to helping parents become aware and develop practical strategies for focusing, exciting, expanding, encouraging, and regulating the child as learning opportunities arise in the course of natural everyday caregiver/child interactions.17

Video Training

The MISC consultants also taught the field team how to videotape 5 minute segments of the caregiver bathing the child, feeding the child, and working with the child. These 15-min recordings were made for the MISC intervention dyads in the home at the start of the year-long training and thereafter every three months. The tapes were played back to the caregivers by the field trainers and used as part of the MISC training during each biweekly session. Similar recordings were also scored for the Control group caregiver/child dyads, but not used in the biweekly training of the caregivers. They were used for scoring as described below.

Video Scoring

The video recordings at baseline, 6 months, and 1 year for both training groups (MISC, Control) were scored by an independent observer at a separate study site, using the Observing Mediated Interactions (OMI) rubric developed by Dr. Klein.9–11 OMI scoring of 15 minute video tapes were scored for the total number of focusing, exciting, expanding, encouraging, and regulating caregiver/child interactions consistent with the MISC training. This measure helped document fidelity of training and served as one of our training outcomes.

At baseline, 6 months, and one year a home visitor independently administered the Caldwell Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) scale.18 This quality of home environment evaluation also included an SES measure based on dwelling (e.g., roofing type, number in household, water source, electricity, and cooking facilities), and material possessions (e.g., farm animals, bicycle, radio, TV/computer/DVD/video access, furnishings, appliances).

Developmental Outcomes

At baseline, 6 and 12 months testers blinded to the treatment arm assessed study children with the Mullen Early Learning Scales (MELS) in a private quiet setting at our study office. Child testing and caregiver questionnaires were done in the local languages of Japhadola, Ateso, or Luganda, depending on what language was spoken in the home. The MELS has scales in motor, language, and overall cognitive skills development.19 Children were also assessed with the Color-Object Association Test (COAT) for memory. This is an experimental test that uses the placement of small toys inside of small colored boxes to test memory.20

While the child was undergoing developmental assessment, the study caregiver was interviewed with the Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) for younger children (1.5 to 5 yrs).21, 22 The CBCL is a psychiatric screening tool for internalizing symptoms (emotional), externalizing symptoms (behavioral), and total symptoms.23

Anthropometric Measurements

At the time of testing, the child’s height, weight, and mid-upper-arm circumference (MUAC) were also measured.

Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25)

The HSCL is a 25-item scale previously used to assess depression and anxiety symptoms, through two syndrome-specific subscales, among adults in HIV-affected Ugandan communities.24 This questionnaire was given to the caregiver during the home evaluation visit at baseline, 6 and 12 months, with caregivers being asked to report how frequently they experienced 25 specific symptoms in the prior 2 weeks using a Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 3 (all the time).

Statistical Analyses

We used a repeated-measure ANCOVA analytic model (RM-ANCOVA) (baseline, 6, and 12 month) to evaluate MELS developmental (Table 2) and COAT memory outcomes and CBCL global psychiatric symptoms (Table 3) across the treatment arms. In this analysis, the group (MISC, Control) by time (baseline, 6, and 12 mos.) interaction indicates a significant outcome difference between the two interventions (Tables 2 – 5). The group-by-time effects were adjusted for baseline age, gender, weight-for-age Z score (Epi Info@ CDC 2000 norms), HSCL-25 caregiver anxiety scores at 12 months, caregiver formal years of schooling (educational level), Caldwell HOME score total at baseline (quality of caregiving), and SES total score at baseline.

Table 2.

P values are presented for the Mullen Early Learning Scales (MELS) outcome measures, from a repeated-measure (baseline, 6 months, 1 year) analysis of covariance (RM-ANCOVA). For each MELS scale measure, the raw score was used in the analysis. The T score (standardized) was used for the early learning composite score. Between-group comparison is for MISC and Control groups. Covariates in the model are age at baseline, Caldwell HOME scale score at baseline, SES total at baseline, Weight-for-age Z score (CDC 2000 norms), Hopkins Symptoms Checklist 25-item scale (HSCL-25) anxiety score for the caregiver at 12 months, caregiver years of formal schooling, and gender. Group by gender is the only interaction effect included in this model. Statistically significant P values are in bold.

| Control Variables | Gross motor | Fine motor | Receptive Language | Expressive Language | Visual Reception | Early Learning Composite | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadj | Adjust | Unadj | Adjust | Unadj | Adjust | Unadj | Adjust | Unadj | Adjust | Unadj | Adjust | |

| Group by Time | .069 | .023 | .145 | .178 | .004 | .004 | .001 | .001 | .676 | .668 | .005 | .006 |

| Child Age | .002 | .002 | .0001 | .0001 | .0001 | .0001 | .0001 | .0001 | .0001 | .0001 | .701 | .365 |

| Caldwell HOME score | .840 | .095 | .039 | .006 | .183 | .011 | ||||||

| SES total (Possessions) | .491 | .378 | .131 | .061 | .326 | .197 | ||||||

| Weight/Age Z | .003 | .121 | .107 | .133 | .049 | .068 | ||||||

| HSCL-25 Caregiver Anxiety (12 mo) | .467 | .173 | .033 | .449 | .146 | .123 | ||||||

| Caregiver Years of Schooling | .605 | .174 | .616 | .351 | .101 | .166 | ||||||

| Group (MISC/Control) | .573 | .911 | .424 | .574 | .925 | .742 | ||||||

| Child Gender | .359 | .053 | .117 | .961 | .363 | .235 | ||||||

| Group by Gender | .794 | .859 | .157 | .314 | .665 | .630 | ||||||

Table 3.

P values are presented for the color-object association test (COAT) memory measures (immediate recall, total recall), from a repeated-measure (baseline, 6 months, 1 year) analysis of covariance (RM-ANCOVA). Unadjusted (Unadj) and Adjusted (Adjust) between-group comparison is for MISC and Control groups. Also presented are the RM-ANCOVA P values with the Achenbach CBCL global scale totals (internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, total symptoms). The raw score is used in the analysis. Covariates in the model are age at baseline, Caldwell HOME scale score at baseline, SES total at baseline, weight-for-age Z score (CDC 2000 norms), Hopkins Symptoms Checklist 25-item scale (HSCL-25) anxiety score for the caregiver at 12mos, caregiver years of formal schooling, and gender. Group by gender is the only interaction effect included in this model. Statistically significant P values are in bold.

| Control Variables | COAT Immediate Recall | COAT Total Recall | CBCL Internalizing Symptoms | CBCL Externalizing Symptoms | CBCL Total Symptoms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadj | Adjust | Unadj | Adjust | Unadj | Adjust | Unadj | Adjust | Unadj | Adjust | |

| Group by Time | .418 | .319 | .134 | .054 | .106 | .854 | .240 | .198 | .162 | .150 |

| Child Age | .0001 | .001 | .0001 | .0001 | .992 | .525 | .822 | .863 | .962 | .651 |

| Caldwell HOME score | .049 | .451 | .674 | .250 | .671 | |||||

| SES Total (Possessions) | .026 | .097 | .062 | .241 | .076 | |||||

| Weight-for-Age Z score | .845 | .987 | .594 | .099 | .570 | |||||

| HSCL Caregiver Anxiety | .663 | .965 | .0001 | .102 | .003 | |||||

| Caregiver Years of Schooling | .780 | .349 | .557 | .433 | .697 | |||||

| Group | .437 | .528 | .225 | .477 | .355 | |||||

| Child Gender | .639 | .654 | .384 | .101 | .581 | |||||

| Group by Gender | .537 | .793 | .427 | .870 | .404 | |||||

Table 5.

P values are presented for the principal quality of caregiving outcome measures, from a repeated-measure (baseline, 6 months, 1 yr) analysis of covariance (RM-ANCOVA). For both principal quality-of-caregiving outcome measures (Caldwell HOME total score and OMI total score). The raw score is used in the analysis. Results are presented for the unadjusted model (Unadjusted) and the RM-ANCOVA additive model. Covariates in the model are age, SES total at baseline, weight-for-age Z score (CDC 2000 norms), Hopkins Symptoms Checklist 25-item scale (HSCL-25) anxiety score for the caregiver at 12 months, caregiver years of formal schooling, and gender. Group by gender is the only interaction effect included in this model. Statistically significant P values are in bold.

| Quality of Caregiving Measures | Caldwell HOME Total Score | Observed Mediated Interactions (OMI) Video Total Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor or Covariate Measure | Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted |

| Group by Time | .0001 | .0001 | .0001 | .0001 |

| Child Age | .575 | .952 | .021 | .012 |

| Caldwell HOME score | .048 | |||

| SES total (Possessions) | .086 | .422 | ||

| Weight-for-Age Z score | .363 | .951 | ||

| HSCL-25 Caregiver Anxiety | .165 | .166 | ||

| Caregiver Years of Schooling | .038 | .780 | ||

| Group | .0001 | .0001 | ||

| Child Gender | .395 | .849 | ||

| Group by Gender | .430 | .267 | ||

Additive models were used in the RM-ANCOVA analyses and only one interaction, gender by group, was included among the control variable analyses. Changes in caregiver HSCL-25 depression and anxiety outcomes were evaluated as outcomes for between group (MISC, Control) differences over time (Table 4). RM-ANCOVA models were also used with quality of caregiving outcomes (HOME, OMI video scores), omitting HOME as a control variable for the OMI video outcome (Table 5). All analyses were conducted with SPSS version 19.

Table 4.

P values are presented for the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist 25-item depression and anxiety scale (HSCL-25) repeated-measure (baseline, 6 mos, 1 yr) analysis of covariance (RM-ANCOVA). The raw score is used in the analysis. Between-group comparison is for MISC and Control groups. Covariates in the model are age of the child at baseline, Caldwell HOME scale score at baseline, SES total at baseline, weight-for-age Z score (CDC 2000), caregiver years of formal schooling, and gender. Group by gender is the only interaction effect included in this model. Statistically significant P values are in bold.

| Control Variables | HSCL Anxiety | HSCL Depression | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

| Group by Time | .422 | .537 | .755 | .766 |

| Child Age | .351 | .600 | ||

| Caldwell HOME score | .019 | .035 | ||

| SES total (Possessions) | .984 | .930 | ||

| Weight-for-Age Z score | .570 | .380 | ||

| Caregiver Years of Schooling | .572 | .576 | ||

| Group | .378 | .174 | ||

| Child Gender | .309 | .069 | ||

| Group by Gender | .440 | .960 | ||

RESULTS

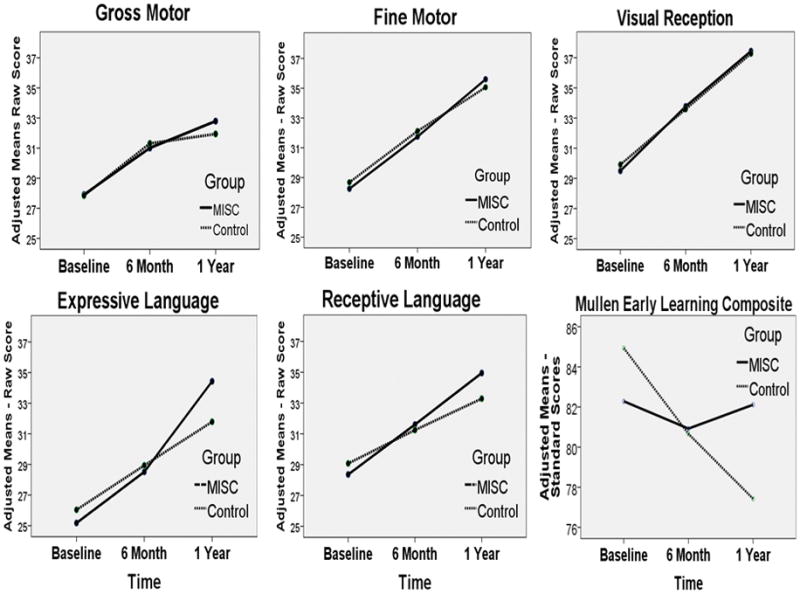

In the RM-ANCOVA analysis for the MELS scale measures, the MISC children showed greater gains than the controls over time (group by time; Table 2) on the MELS scales of Receptive Language (P = .004), Expressive Language (P = .001), and the Composite score of overall cognitive ability (P = .006). The MELS Composite score is a global measure of cognitive ability which combines the cognitive scales of Visual Reception, Fine Motor, Receptive Language, and Expressive Language. Figure 1 depicts the adjusted means from this analysis for the MISC and Control groups across the 3 time points during the training year (baseline, 6 months, 1 year) for each of the MELS scales and the MELS Composite (cognitive ability) score.

Figure 1.

depicts the adjusted group mean score across the three time points (baseline, 6 months, 1 yr for the MISC (blue) and control (green) caregiver training intervention groups. The means are adjusted according to the RM-ANCOVA model presented in Table 2. Each Mullen Early Learning Scale (MELS) is presented and the MELS composite score for the four cognitive scales (Fine Motor, Expressive Language, Receptive Language, Visual Reception).

For the control variables in the RM-ANCOVA analysis for the MELS outcomes, the Caldwell HOME score at baseline was predictive of the repeated MELS measures of Receptive Language (P = 0.039), Expressive Language (P = 0.006), and the Composite score (P = 0.011) (Table 2). Weight-for-Age z scores (WAZ) was significantly predictive of the MELS scale measures of Gross Motor (P = 0.003) and Visual Reception (P = 0.049). HSCL-25 caregiver anxiety scores at the one-year assessment were predictive of Receptive Language (P = 0.033) (Table 2).

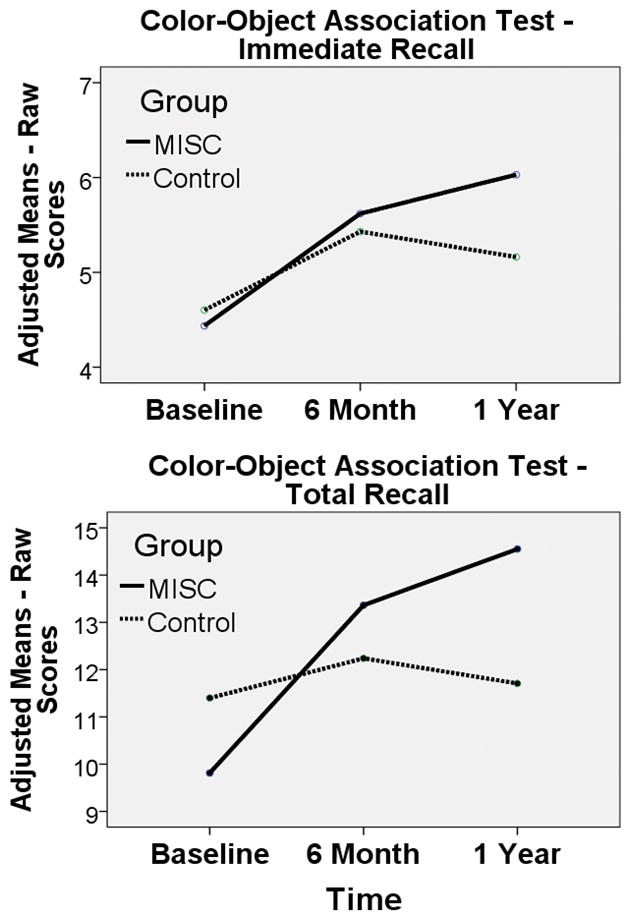

In the RM-ANCOVA analysis for the COAT memory measures, there were no significant group-by-time effects for immediate recall (memory), although the MISC children improved more than the control children on COAT total recall (P = 0.054) (Table 3 and Figure 2). Caldwell HOME score (P = 0.049) and SES (P = 0.026) were significantly predictive of COAT immediate recall performance (Table 3).

Figure 2.

depicts the adjusted group mean score across the three time points (baseline, 6 months, 1 year) for the MISC (blue) and Control (green) caregiver training intervention groups. The means are adjusted according to the RM-ANCOVA model presented in Table 3. Both Color-Object Association Test (COAT) scores are presented: Immediate Recall (memory) and Total Recall (learning).

Group-by-time was not significant for CBCL internalizing, externalizing, and total symptoms (Table 3). However, caregiver HSCL anxiety was significantly predictive of the child’s CBCL internalizing symptoms (P< 0.0001) (e.g., anxiety, depression, somatic complaint) and CBCL total symptoms (P = 0.003).

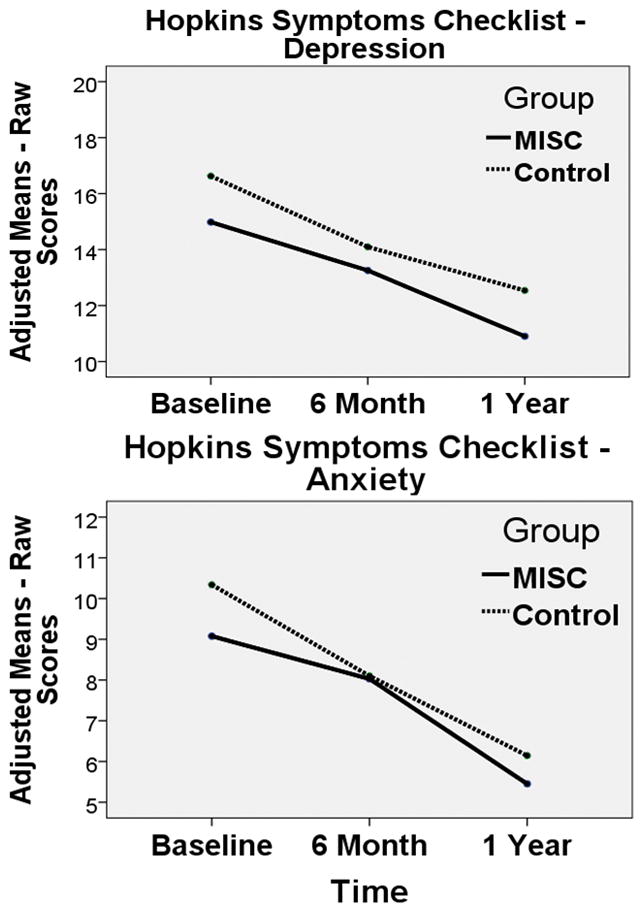

Over the intervention year, caregiver HSCL-25 depression symptoms improved for caregivers in both the MISC and Health/Nutrition (Control) groups with no significant differences for anxiety symptoms (Figure 4). MISC caregivers did not present with greater improvement than Controls for either depression or anxiety symptoms (Table 4). However, quality of caregiving as indicated by the Caldwell HOME score was significantly related to both caregiver Depression improvement over time (P = 0.035) and Anxiety (P = 0.019) (Table 4).

Figure 4.

depicts the adjusted group mean score for the Hopkins Symptoms Checklist, 25 item questionnaire (HSCL-25) across the three time points (baseline, 6 months, 1 year) for the MISC (blue) and Control (green) caregiver training intervention groups. The means are adjusted according to the RM-ANCOVA model presented in Table 4.

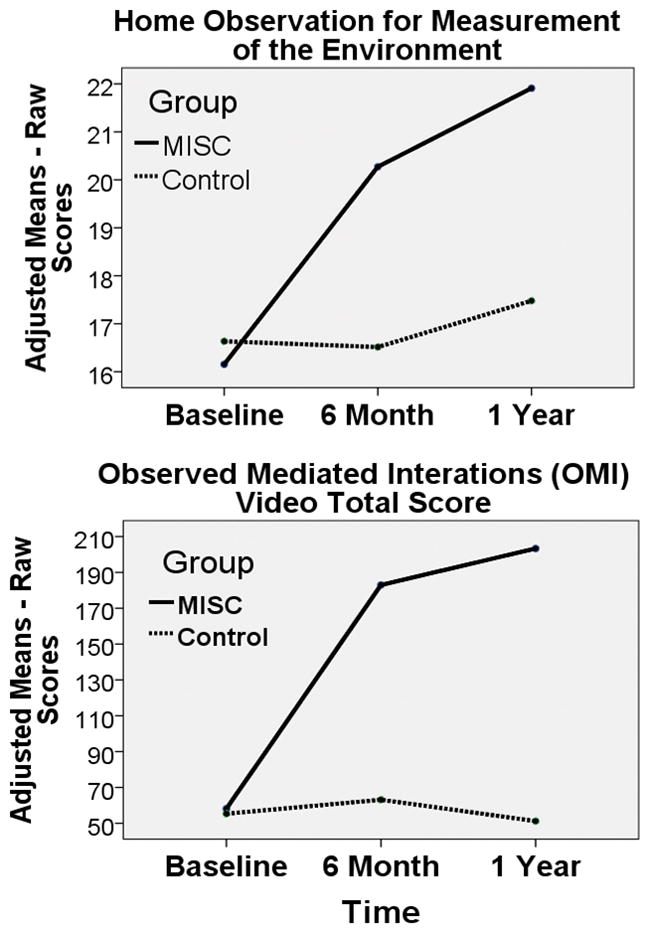

Both Caldwell HOME and OMI total score (from the 15 min caregiving videos) significantly improved for the MISC dyads compared to the Control group (P< 0.0001) (Table 5 and Figure 3). Caregiver level of education (years of schooling) was significantly related to the Caldwell HOME total score (P = 0.038) (Table 5).

Figure 3.

depicts the adjusted group mean score across the three time points (baseline, 6 months, 1 year) for the MISC (blue) and Control (green) caregiver training intervention groups. The means are adjusted according to the RM-ANCOVA model presented in Table 5. Both quality-of-caregiving outcome measures are presented: Caldwell Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment (HOME) total and Observed Mediated Interactions (OMI) total score from the 15 minute video evaluation of the caregiver s feeding, bathing, and working with the child.

DISCUSSION

A year-long caregiver training program to enhance caregiver/child day-to-day interactions (MISC) significantly improved language and overall cognitive ability when compared to a health/nutrition education curriculum intervention. These findings were consistent with those from a similar study of preschool rural Ugandan children with HIV.25

However, unlike the MISC intervention study findings with children with HIV, MISC caregivers in the present study did not experience significantly greater improvement in their depression and anxiety symptoms compared to the Control caregivers. The emotional wellbeing of both intervention groups improved during the treatment year. The social support derived even from a health/nutrition educational curriculum can improve emotional well-being in HIV mothers. Furthermore, better emotional outcomes for the caregiver were related to both better emotional outcomes for the child (CBCL internalizing and total symptoms) and better caregiving as measured by the Caldwell HOME scale.

The relationship between nutritional wellbeing as measured by physical development and the Mullen Gross Motor development for our study children were evident in this study (see the relationship between the covariate of weight-for-age and the Mullen Gross Motor scale in Table 2). We obtained similar findings in a MISC-intervention study of rural Ugandan children infected by HIV.25 Nutritional intervention was not a part of the present study design. However, it is an important consideration in caregiving quality for the developmental enhancement of HIV-affected children in low-resource settings. Maternal HIV disease in a rural subsistence agricultural low-resource setting can severely disrupt food security for the entire family.4–6 Chronic nutritional hardship can severely undermine early childhood development, compounding the risk from compromised caregiving and other aspects of HIV exposure.7, 8

MISC as a Culturally Appropriate Intervention

The MISC approach has a clear and well-developed theoretical foundation. MISC has a strong emphasis on the importance of the social/interactive/emotional domains as integrally linked to intellectual and cognitive development. Most of the MISC training of caregivers is devoted to helping parents become aware and develop practical strategies for focusing, exciting, expanding, encouraging, and regulating the child as learning opportunities arise in the course of natural everyday caregiver/child interactions.9–11 Because of the facilitative nature of the program, it does not rely on outside resources or materials, and can be implemented with most children in a variety of contexts where caregiver/child interactions naturally take place.

The cultural emphasis in African village life on the nurturing of children is a good fit for the MISC, which is a method for sensitizing mothers to the positive aspects of their current childrearing interactions. Similarly to what Klein found in Ethiopia, we conclude that MISC can be readily understood and implemented by caregivers as part of their own childrearing goals.9 MISC principles can be readily translated into actions within the cultural and contextual constraints of everyday living in each of their families.9–11

In the present study we excluded children with severe disabilities. However, MISC interventions have proven effective in help intellectually disabled children and adults achieve greater autonomy and functionality in activities of daily living.26–28 We propose that MISC can also prove effective and sustainable as a means of intervention for African children in low-resource settings where rehabilitative services and programs are not available or accessible. This is perhaps the greatest humanitarian potential of MISC as an intervention in Africa.

MISC in Early Childhood Brain Development

One to 5 years of age is a critical developmental period for children, during which time they develop the dynamic capacity to benefit from new learning experiences. There is a general consensus from developmental research that adult-child interactions are of central importance in this process.29 Farah and colleagues (2008) observed a relationship between parental nurturance and memory development. This relationship was consistent with the animal literature on maternal buffering of stress hormone effects on hippocampal development.30 Rao et al. (2009) observed that parental nurturance at age 4 predicts the volume of the left hippocampus in adolescence, with warmer and more loving nurturance associated with smaller hippocampal volume.

Also, the association between parental nurturance and hippocampal volume disappears at 8 years of age. They concluded that this supports the existence of a sensitive developmental period for brain maturation, especially before 4 years of age.31 The caregiver provides for secure emotional attachments in a nurturing environment, creating learning experiences that allows a child’s neurocognitive ability to blossom.13, 32 Effective mediational behaviors by caregivers were found to be significantly related to children’s social-emotional stability and the willingness to explore and learn about the world around them.12, 13 This premise is foundational to the MISC method.

Conclusion

Our caregiver training intervention is evidence-based and family-oriented that has been effectively adapted for use in rural African low-resource settings. Our intervention enhanced caregiving quality and subsequent cognitive development in at-risk children. Both the MISC and health/nutrition curriculum interventions provided psychosocial support on a biweekly basis and diminished depressive symptoms in our caregivers, most of whom were HIV-infected mothers. MISC, therefore, may have multiples benefits for women and their children affected by HIV in low-resource settings. This is because it has the potential of enhancing caregiver sensitivity and responsiveness to the needs of their children. Evidence from our MISC intervention study with Ugandan HIV-infected young children suggest that this can lead to stronger caregiver/child attachment resulting in timelier seeking of medical treatment and lower mortality for children with HIV in low-resource settings.25

Since MISC relies on caregiver/child interactions, and not on outside human or material resources, it has good potential for future dissemination and sustainability in impoverished communities affected by HIV. We selected MISC for our caregiver training intervention because it has been shown to be culturally adaptable to different low resource settings in Africa.10 The fundamental premise of this approach is that mediated learning best occurs interactively, when the caregiver interprets the environment for the child. As such, ours is one of the few culture-appropriate and sustainable evidence-based interventions that can be readily and effectively implemented globally in low-resource settings with children generally at risk from disease, malnutrition, or neglect.11

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grants R34 MH082663 (PI: Boivin) and RO1 HD070723 (PIs: Boivin, Bass). Dr. Pim Brouwers served as program officer for the NIMH R34 award and his support throughout this project is greatly appreciated. The study sponsor had no role in the study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Roland Namwanja (on-site study coordinator), Julius Caesar Ojuka, Jorem Awadu, Fiona Bukenya, Miriam Namirembe, Awau Agnes, Ekisa David, Okello Emmanuel, and Emily Keneema comprised the field team responsible for the intervention training of caregivers, caregiver and child assessments, translation into the local languages, and clinical care. Their efforts made this study possible. We are grateful to the Uganda Community Based Association for Child Welfare (UCOBAC) for the use of their curriculum for our control group intervention. University of Michigan medical students Alec Anderson, Michael Hawking, and Brittany Noble helped in the scoring and data management of the assessments during their summer research internship, sponsored by the University of Michigan Medical School Global Reach Program.

Funding Sources: All phases of this study were supported by NIH grants R34 and RO1 HD070723.

Abbreviations

- CBCL

Achenbach Child Behavior Checklist

- COAT

Color-Object Association Test

- HAART

Highly Active Anti-Retroviral Therapy

- HAZ

Height-for-age adjusted Z score

- HOME

Caldwell Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment

- HIV

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- HSCL-25

Hopkins Symptoms Checklist – 25 items

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- IDRC

Infectious Disease Research Collaboration

- MELS

Mullen Early Learning Scales of Child Development

- MISC

Mediational Intervention for Sensitizing Caregivers

- OMI

Observed Mediated Interactions

- RM-ANCOVA

Repeated Measure Analysis of Covariance

- SES

Socio-Economic Status

- UCOBAC

Uganda Community Based Organization for Child Welfare

- UNCST

Ugandan National Council for Science and Technology

- WAZ

Weight-for-Age adjusted Z score

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.UNAIDS. UNAIDS Report on the global AIDS epidemic/2010: Joint United Nations Programmes on HIV/AIDS. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ronald AR, Sande MA. HIV/AIDS care in Africa today. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(7):1045–1048. doi: 10.1086/428360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bose S. ProQuest Information & Learning, Jul 1997 AAM9719709. 58. 1997. An examination of adaptive functioning in HIV infected children: Exploring the relationships with HIV disease, neurocognitive functioning, and psychosocial characteristics; p. 409. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caruso N. Refuge from the Lord’s Resistance Army in Uganda: a report from a Medecins Sans Frontieres team leader. Emerg Med Australas. 2006;18(3):295–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2006.00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fabiani M, Nattabi B, Opio AA, Musinguzi J, Biryahwaho B, Ayella EO, et al. A high prevalence of HIV-1 infection among pregnant women living in a rural district of north Uganda severely affected by civil strife. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100(6):586–593. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orach CG, De Brouwere V. Integrating refugee and host health services in West Nile districts, Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21(1):53–64. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czj007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foster G, Williamson J. A review of current literature on the impact of HIV/AIDS on children in sub-Saharan Africa. Aids. 2000;14 (Suppl 3):S275–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boivin MJ, Green SD, Davies AG, Giordani B, Mokili JK, Cutting WA. A preliminary evaluation of the cognitive and motor effects of pediatric HIV infection in Zairian children. Health Psychol. 1995;14(1):13–21. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klein P, Rye H. Interaction-Oriented Early Intervention in Ethiopia: the MISC Approach. Infants and Young Children. 2004;17:340–354. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein PS, editor. Seeds of hope: twelve years of early intervention in Africa. Oslo, Norway: unipub forlag; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klein PS, editor. Early Intervention: cross-cultural experiences with a mediational approach. New York, NY: Garland Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feuerstein R. The dynamic assessment of retarded performers. New York: University Park Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feuerstein R. Instrumental enrichment: Redevelopment of cognitive functions of retarded performers. New York: University Park Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakasujja N, Skolasky RL, Musisi S, Allebeck P, Robertson K, Ronald A, et al. Depression symptoms and cognitive function among individuals with advanced HIV infection initiating HAART in Uganda. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:44. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durkin MS, Davidson LL, Desai P. Validity of the ten-question screen for childhood disability: results from population based studies in Bangladesh, Jamaica and Pakistan. Epidemiology. 2005;5:283–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durkin MS, Wang W, Shrout PE, Zaman SS, Hasan ZM, Desai P, et al. Evaluating a ten questions screen for childhood disability: reliability and internal structure in different cultures. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48(5):657–666. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00163-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein PS. More Intelligent and Sensitive Child. Ramat-Gan, Israel: Bar-Ilan University; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caldwell BM, Bradley RH. Home Observation for Measurement of the Environment. Little Rock, AR: University of Arkansas Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mullen EM. Mullen Scales of Early Learning:AGS Edition. Minneapolis, MN: American Guidance Services; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jordan CM, Johnson AL, Hughes SJ, Shapiro EG. The Color Object Association Test (COAT): the development of a new measure of declarative memory for 18- to 36-month-old toddlers. Child Neuropsychology. 2008;14(1):21–41. doi: 10.1080/09297040601100430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: an integrated system of multi-informant assessment. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Multicultural supplement to the manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bangirana P, Nakasujja N, Giordani B, Opoka RO, John CC, Boivin MJ. Reliability of the Luganda version of the Child Behaviour Checklist in measuring behavioural problems after cerebral malaria. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2009;3:38. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-3-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bass J, Neugebauer R, Clougherty KF, Verdeli H, Wickramaratne P, Ndogoni L, et al. Group interpersonal psychotherapy for depression in rural Uganda: 6-month outcomes: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:567–573. doi: 10.1192/bjp.188.6.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boivin MJ, Bangirana P, Page CF, Shohet C, Givon D, Bass JK, et al. A year-long caregiver training program to improve neurocognition in preschool Ugandan children with HIV. 2012 doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318285fba9. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein PS. Improving the Quality of Parental Interaction with very Low Birth Weight of Children: a Longitudinal Study Using Mediated Experience Model. Infant Mental Health Journal. 1991;12(4):321–337. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein PS, Alony S. Immediate and Sustained Effects of Maternal Mediation Behaviors in Infancy. Journal of Early Intervention. 1993;71(2):177–193. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lifshitz H, Klein PS, Cohen SF. Effects of MISC intervention on cognition, autonomy, and behavioral functioning of adult consumers with severe intellectual disability. Res Dev Disabil. 31(4):881–894. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonnier C. Evaluation of early stimulation programs for enhancing brain development. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97(7):853–858. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Farah MJ, Betancourt L, Shera DM, Savage JH, Giannetta JM, Brodsky NL, et al. Environmental stimulation, parental nurturance and cognitive development in humans. Dev Sci. 2008;11(5):793–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rao H, Betancourt L, Giannetta JM, Brodsky NL, Korczykowski M, Avants BB, et al. Early parental care is important for hippocampal maturation: evidence from brain morphology in humans. Neuroimage. 2009;49(1):1144–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vygotsky LS. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]