Abstract

Biotrophic pathogens, like the powdery mildew fungi, require living plant cells for their growth and reproduction. During infection, a specialized structure called the haustorium is formed by the fungus. The haustorium is surrounded by a plant cell-derived extrahaustorial membrane (EHM). Over the EHM, the fungus obtains nutrients from and secretes effector proteins into the plant cell. In the plant cell these effectors interfere with cellular processes such as pathogen defense and membrane trafficking. However, the mechanisms behind effector delivery are largely unknown. This paper provides a model for and new insights into a putative transfer mechanism of effectors into the plant cell. We show that silencing of the barley Sec61βa transcript results in decreased susceptibility to the powdery mildew fungus. HvSec61βa is a component of both the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) translocon and retrotranslocon pores, the latter being part of the ER-associated protein degradation machinery. We provide support for a model suggesting that the retrotranslocon function of HvSec61βa is required for successful powdery mildew fungal infection. HvSec61βa-GFP and a luminal ER marker were co-localized to the ER, which was found to be in close proximity to the EHM around the haustorial body, but not the haustorial fingers. This differential EHM proximity suggests that the ER, including HvSec61βa, may be actively recruited by the haustorium, potentially to provide efficient effector transfer to the cytosol. Effector transport across this EHM-ER interface may occur by a vesicle-mediated process, while the Sec61 retrotranslocon pore potentially provides an escape route for these proteins to reach the cytosol.

Keywords: powdery mildew, haustorium, extrahaustorial membrane (EHM), endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation (ERAD), Sec61 complex, susceptibility factor

INTRODUCTION

Many filamentous plant pathogenic fungi and oomycetes rely on placing a feeding structure, a so-called haustorium inside host cells in order to exploit host resources and to transfer effector proteins to the host cytosol. By unknown mechanisms, these pathogens trigger the host cells to generate an extrahaustorial membrane (EHM), which allows the host cells to stay alive despite the severe haustorial invasions (Gan et al., 2012). In between the haustorium and the EHM, a sealed compartment, called the extrahaustorial matrix (EHMx) is present. Many of these pathogens, such as powdery mildew fungi, have genetically lost certain general life-sustaining processes during their evolution (Spanu et al., 2010). This prevents them from living on dead biological material, making them strict biotrophs. In the meantime, they secrete hundreds of effectors from the haustoria, mediated by signal peptides (SPs) and default secretion. Many of these effectors are transferred to the host cytosol, where they play important roles in pathogenicity by assisting in nutrient acquisition, suppression of defense and reprogramming cellular processes (Bozkurt et al., 2012; Pedersen et al., 2012; Saunders et al., 2012). An inherent problem, which is poorly understood, concerns how the effectors escape the EHM-delimited haustorial compartment to access the plant cytosol. This requires a mechanism to cross membranes, such as a protein transmitting pore. Essentially, the only currently established element of this process is the RxLR-dEER motif, located a few amino acids downstream of the SP cleavage site in many oomycete effectors. By an unknown process, this motif guides the effectors to be transported across membranes and allows them to enter the host cytosol (Whisson et al., 2007).

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a major organelle in eukaryotic cells, which forms an extended network, functioning in, e.g., protein processing and sorting. Voegele et al. (2009) have previously suggested that the ER plays a role in transfer of effector to the plant cytosol. In the ER, proper folding and modification of proteins is assisted and validated by the ER quality control (ER-QC) machinery. If proteins finally fail the quality check, they are recognized by the ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) machinery and retrotranslocated into the cytosol to be degraded by proteasomes (Nakatsukasa and Brodsky, 2008). Effectors may exploit this retrotranslocon pore in order to get access to the plant cytosol. Different multicomponent retrotranslocon pores have been described in yeast and mammals, in which, e.g., Derlin, Hrd, and Sec61 proteins are major elements (Kawaguchi and Ng, 2007; Nakatsukasa and Brodsky, 2008). The ERAD substrates are ubiquitinated during the retrotranslocation process by retrotranslocon-associated ubiquitin ligases, and this targets them for proteasomal degradation as soon as they reach the cytosol (Carvalho et al., 2006, 2010). The Sec61 pore can translocate proteins bi-directionally, and it is primarily known as the translocon pore, mediating the process of SP-dependent protein translocation into the ER. The Sec61 pore is a doughnut-shaped heterotrimeric complex, consisting of the subunits, Sec61α, Sec61β, and Sec61γ. SP and Sec61-dependent translocation into the ER can occur either co- or post-translationally (Zimmermann et al., 2011). The ERAD pathway has in several cases been shown to be recruited by opportunistic pathogens for transfer of polypeptides into the host cell cytosol. For example, cholera toxin, shiga toxin, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin enter the cytosol through retrotranslocon pores, but escape from ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation (Rodighiero et al., 2002; Blanke, 2006). Retrotranslocation of cholera toxin occurs through the Sec61 retrotranslocon pore, and depletion of the Sec61 complex prevented the retrotranslocation of this toxin into the cytosol (Schmitz et al., 2000; Teter et al., 2002).

Here we aimed at studying the role of the Sec61 pore in plant susceptibility to the powdery mildew fungus. Barley (Hordeum vulgare) has two Sec61α, two Sec61β, and one Sec61γ protein1 (Deng et al., 2007; Mayer et al., 2012), and to unravel the role of the pore, we made use of the fact that the Sec61β component is essential for retrotranslocon activity for various substrates, but less important for translocon activity under non-stressed conditions (Finke et al., 1996; Van den Berg et al., 2004; Liao and Carpenter, 2007; Kelkar and Dobberstein, 2009; Zhao and Jantti, 2009; Wang et al., 2010; Guerriero and Brodsky, 2012). We show that silencing of HvSec61βa reduced the susceptibility of barley epidermal cells to the powdery mildew fungus (Blumeria graminis f.sp. hordei, Bgh). In addition, the HvSec61βa-GFP-labeled ER network is differentially associated to the body, and not the fingers of the powdery mildew fungal haustorium. To explain the role of the Sec61βa in pathogenicity, we propose a model in which the fungus actively recruits the ER in order to exploit the Sec61 pore for pathogenicity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PLANTS AND FUNGI

Barley (Hordeum vulgare) cv. Golden Promise plants were used for transient transformation and subsequent studies with and without powdery mildew fungal inoculation. The barley powdery mildew fungus (Blumeria graminis f.sp. hordei, Bgh), isolate DH14, was maintained on susceptible barley, cv. Golden Promise, grown at 20°C, 16 h light (150 μE/sm2)/8 h dark, by weekly inoculum transfer. These growth conditions were used throughout the studies.

CLONING

To generate a gene-specific RNA interference (RNAi) construct to silence HvSec61βa (AK252927.1), its coding sequence was PCR-amplified using the primer pair Sec61βa_F1 (CACCATGGTGGCTAATGGTGACG) and Sec61βa_R1 (GGGGTGCGGTACAGCTTTC) on cDNA generated from mRNA isolated from 7-day-old barley leaf material. The PCR product was TOPO-cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen). Positive clones were validated by sequencing. Using Gateway LR cloning, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen), the insert was transferred to the 35S-promoter driven destination vector, pIPKTA30N (Douchkov et al., 2005), to generate the final RNAi construct. To generate the Sec61βa-GFP construct for localization, the full-length Sec61βa coding sequence, without stop-codon, was amplified with the primer pair HvSec61βa_KZK_GWY_FW (GGGGACAAGTTTGTACAAAAAAGCAGGCACCATGGTGGCTAATGGTGACGCCCCT) and HvSec61βa_ns_GWY_Rv (GGGGACCACTTTGTACAAGAAAGCTGGGTTATTAGGGGTGCGGTACAGCTTGCC) on the pENTR clone described above, and using a BP clonase reaction it was cloned into the pDONR201 vector (Invitrogen). Positive clones were confirmed by sequencing. Using a Gateway LR clonase reaction according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen), the insert was transferred to the 35S-promoter-driven destination vector, P2GWF7 (Curtis and Grossniklaus, 2003). All final clones were verified by restriction enzyme digestion.

PARTICLE BOMBARDMENT

Transformation of gene constructs into epidermal cells of 7-day-old barley leaves was conducted by particle bombardment, essentially as described by Douchkov et al. (2005). For transient induced gene silencing (TIGS) studies, the constructs were co-transformed with a β -glucuronidase (GUS) reporter construct, followed by inoculation with Bgh 2 days later (inoculation density around 200 conidia per mm2). Three days after inoculation, the leaves were GUS-stained, and the relative susceptibility index was calculated by dividing the number of GUS-stained epidermal cells containing a haustorium by the total number of GUS-stained cells. The data were normalized to the empty vector (pIPKTA30N) control. The experiments were repeated at least three times. A cell viability test was performed by co-transformation of the HvSec61βa RNAi construct or the empty vector control, pIPKTA30N, with the anthocyanin biosynthesis-activating construct, pBC17 (Schweizer et al., 2000). Two days after transformation, the leaves were inoculated with Bgh at a density of 200 conidia per mm2, and after another 3 days, the anthocyanin-stained cells were counted. Constructs for marker proteins, fused with fluorescent proteins, were transformed and inoculated with Bgh 1 day later, and examined by confocal microscopy 2 days after transformation.

CONFOCAL MICROSCOPY

A Leica SP5-X confocal laser scanning microscope, mounted with a 63 × 1.2 numerical aperture water-immersion objective, was used. For fluorescent protein detection and localization, GFP was excited at 488 nm, and the fluorescence emission was detected between 518 and 540 nm. mCherry fluorescence was excited at 543 nm and fluorescence emission was detected between 590 and 640 nm. 3D projections were created using the Image Surfer 1.2 software2 (Feng et al., 2007).

RESULTS

HvSec61βa IS A POTENTIAL SUSCEPTIBILITY FACTOR FOR THE BARLEY POWDERY MILDEW FUNGUS

In barley two Sec61β genes have been identified, which are named HvSec61βa and HvSec61βb. Interestingly, the HvSec61βa transcript accumulates in leaves after attack by Bgh3 (Dash et al., 2012). Therefore, we selected to analyze the role of HvSec61βa in the barley/Bgh interaction, and performed single cell TIGS of this gene. A 35S-promoter-driven RNAi construct, covering the full-length coding region of this gene, was generated and transiently transformed together with a GUS reporter-gene construct into barley epidermal cells (Douchkov et al., 2005). After 2 days, the leaves were inoculated with Bgh and transformed cells were stained for GUS activity 3 days thereafter. Infection success of Bgh was evaluated microscopically by scoring the total number of GUS-stained cells and the number of GUS-stained cells containing one or more haustoria. Subsequently, the data were normalized to the empty vector control. The RNAi construct of HvSec61βa resulted in more than 40% reduction in susceptibility to Bgh (Figure 1A). As a positive control, the relative susceptibility of cells transformed with an Mlo-RNAi construct was included (Douchkov et al., 2005). These cells were 70% less susceptible than the control cells. In order to confirm that the RNAi construct in fact results in silencing of HvSec61βa, we co-transformed barley epidermal cells with the RNAi construct of HvSec61βa and a 35S promoter-driven HvSec61βa-GFP fusion construct. Five days after transformation together with a reference construct for cytosolic mCherry expression, confocal imaging revealed that the RNAi construct prevented appearance of GFP signal, while it did not affect the signal from mCherry in the same cell (Figure 1B). The reduced HvSec61βa-GFP signal indicated that the HvSec61βa RNAi silencing construct indeed induced degradation of HvSec61βa encoding mRNA and likely as well impaired endogenous HvSec61βa transcript and protein accumulation. Thus, the observed increased resistance of HvSec61βa-silenced cells indicates a potential role of HvSec61βa as a susceptibility factor for efficient Bgh infection.

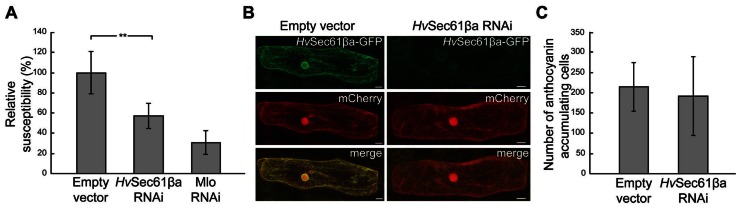

FIGURE 1.

Silencing of HvSec61βa reduces susceptibility to Bgh without affecting plant cell viability. (A) Susceptibility after co-transformation of empty vector control, HvSec61βa-RNAi and Mlo-RNAi constructs with a GUS-reporter construct into barley epidermal cells, followed by inoculation with Bgh 3 days later. The relative susceptibility was calculated as described in Materials and Methods. Mlo-RNAi was used as a positive control. Error bars represent standard deviation (SD). **, P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test). (B) HvSec61βa-RNAi reduced the GFP signal originating from HvSec61βa-GFP, but not the fluorescence signal from cytosolic mCherry 5 days after transformation. Micrographs show maximum intensity projections. (C) Number of pBC17-transformed cells accumulating anthocyanin, reflecting cell viability, after co-bombardment with either an empty vector control or the HvSec61βa-RNAi construct on similarly sized pieces of leaf. Two days after bombardment, leaves were inoculated with Bgh, and the number of anthocyanin-accumulating cells was scored 3 days later (n = 4).

In order to analyze whether the reduced susceptibility could be due to reduced viability of the cells in which HvSec61βa was silenced, a second experiment was performed. Co-transformation was performed with an anthocyanin biosynthesis gene activation construct, pBC17, causing the transformed cells to accumulate the red anthocyanin pigment as long as they stay alive (Schweizer et al., 2000). Two days after transformation, the leaves were inoculated with a high density of Bgh conidia (≈200 per mm2). Similar numbers of anthocyanin accumulating cells were detected in HvSec61βa-silenced and non-silenced cells after Bgh infection (Figure 1C). Therefore, this result confirmed that the HvSec61βa RNAi construct did not affect the viability of the barley cells after inoculation.

HvSec61β LOCALIZATION IN UNINFECTED AND INFECTED BARLEY CELLS

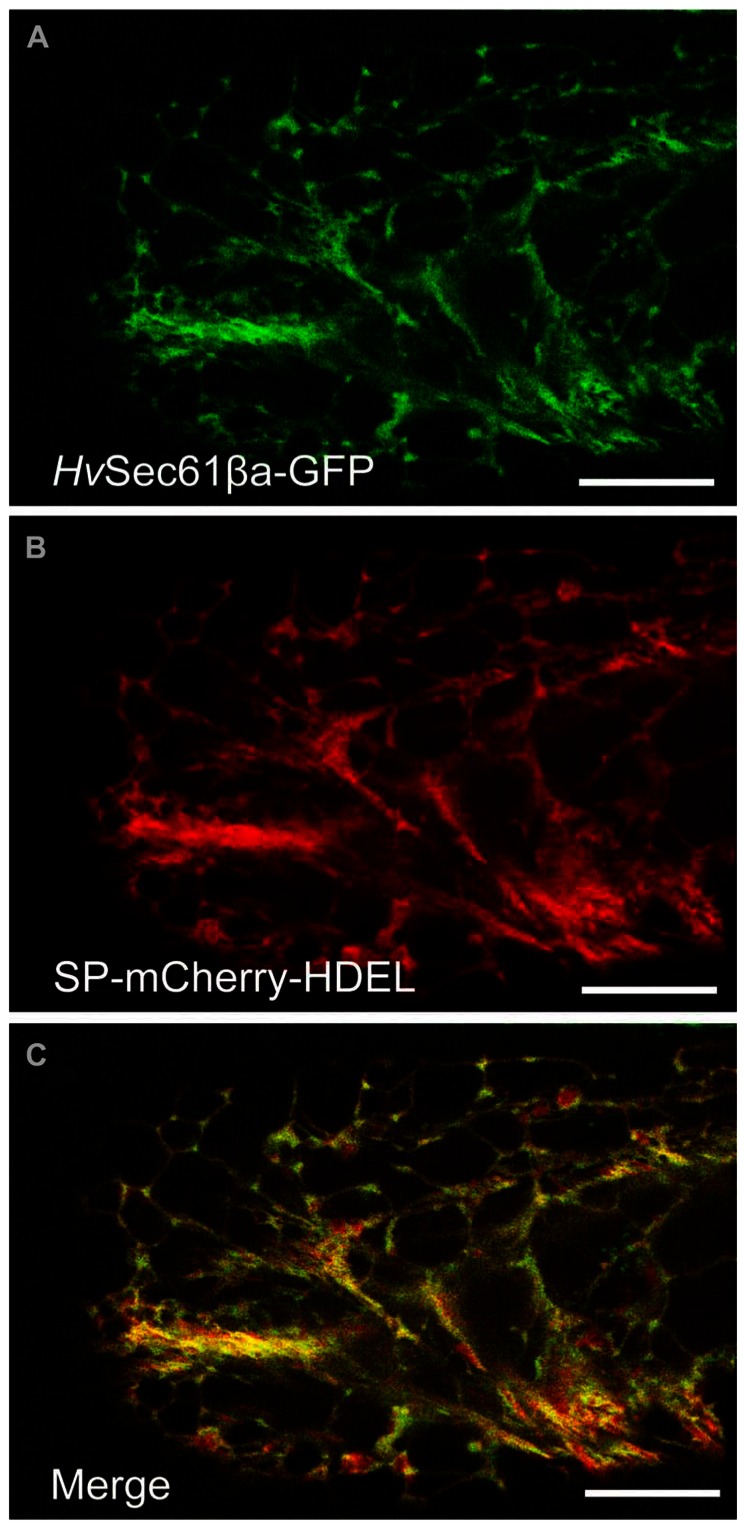

Next we aimed to subcellularly localize HvSec61βa to search for clues for the powdery mildew-related function of this protein. Sec61β is a small ~8 kDa protein with a single transmembrane domain, and GFP-tagging has previously been used for its localization (Rolls et al., 1999; Voeltz et al., 2006). Therefore, we co-expressed our 35S promoter-driven HvSec61βa-GFP fusion construct together with a 35S promoter-driven SP-mCherry-HDEL construct (Nelson et al., 2007) in infected and uninfected barley epidermal cells. The SP targets mCherry to the ER and the ER retrieval motif HDEL (His-Asp-Glu-Leu) at the C-terminus retains it in the lumen of the ER (Gomord et al., 1997). Confocal images of epidermal single cells expressing HvSec61βa-GFP and SP-mCherry-HDEL were recorded 48 h after particle bombardment (Figure 2). Intense GFP signal was observed in the ER cortical network throughout the cells expressing GFP-tagged HvSec61βa (Figure 2A). In addition, the HvSec61βa-GFP signal largely colocalized with mCherry signal from the luminal ER marker (Figures 2B,C). The colocalisation is near perfect in the tubular parts of the ER, while the cisternal parts have relatively more mCherry signal. This likely reflects that HvSec61βa-GFP is membrane bound, and that the soluble mCherry luminal marker dominates the more voluminous cisternal ER. In conclusion, our observations indicate that HvSec61βa is localized to all parts of the ER.

FIGURE 2.

HvSec61βa co-localizes with an ER luminal marker. (A) Maximum intensity projection of a z-series of confocal images of a barley epidermal cell expressing HvSec61βa-GFP reveals the ER localization of HvSec61βa-GFP with the typical distribution within the reticular ER network. (B) In the same epidermal cell, the 35S promoter-driven SP-mCherry-HDEL construct is expressed and labels the ER. (C) The merged image shows that the HvSec61βa-GFP and SP-mCherry-HDEL signals largely overlap. Scale bar, 20 μm.

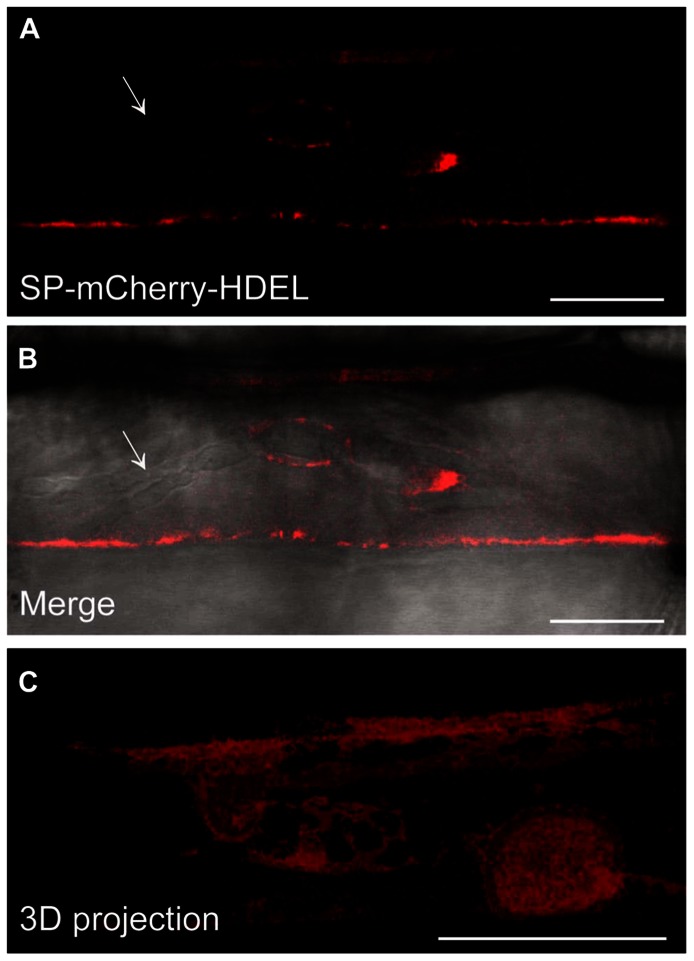

Since we confirmed the ER localisation of HvSec61βa-GFP in barley and have observed increased resistance after silencing this gene, we were interested in knowing how the ER changes its location after pathogen attack. It is often described that infected host cells re-localize organelles and specific proteins, which results in their accumulation at the pathogen attack site (Takemoto et al., 2003; Koh et al., 2005; Caillaud et al., 2012). We used the 35S promoter-driven SP-mCherry-HDEL construct to study the localization of the ER after attack by Bgh. Confocal imaging of an infected barley cell revealed that the mCherry ER-luminal marker was located around the body of the Bgh haustorium. Meanwhile, this ER marker was most often not present around the haustorial fingers (Figures 3A,B). In a 3D projection (Figure 3C) of the mCherry fluorescent signal, this distinction between the haustorial body and fingers is clearly visible. These observations revealed that the ER network is in close proximity to the EHM around the haustorial body.

FIGURE 3.

The SP-mCherry-HDEL ER marker localizes around the Bgh haustorial body. (A,B) Confocal images of infected barley epidermal cell 48 h after inoculation with Bgh. The fluorescent signal of SP-mCherry-HDEL (A) localizes to the ER and surrounds the haustorium inhomogeneously. No fluorescence signal of SP-mCherry-HDEL was observed along the haustorial fingers (arrow). The merged image (B) displays the haustorium structure in bright field, overlaid with the fluorescence signal. To visualize the ER tubules around the haustorial body, a 3D projection of a z-series of confocal images (C) was generated (Image Surfer 1.2). Scale bar, 10 μm.

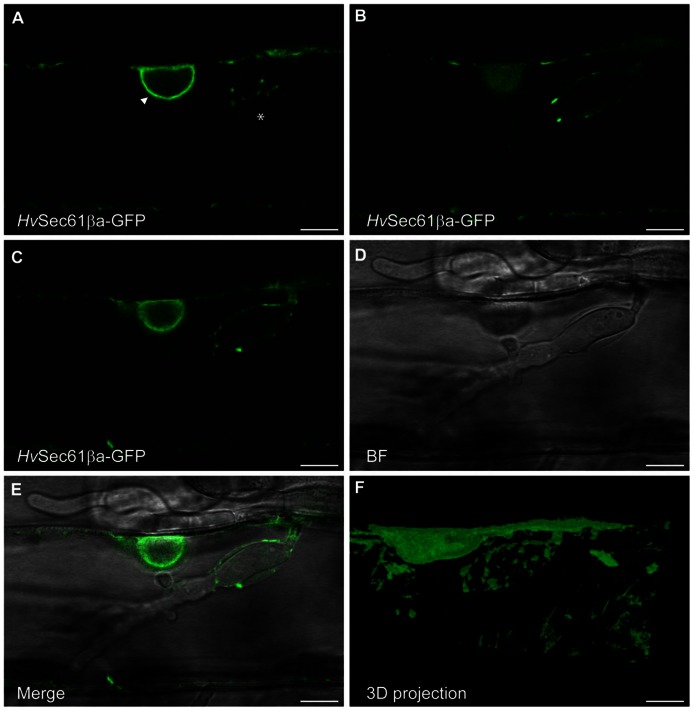

Similar to the mCherry ER-luminal marker (Figure 3), the HvSec61βa-GFP signal was present in the ER network around the Bgh haustorial body as well (Figure 4). Contiguous accumulation of HvSec61βa-GFP was detected around the nucleus, which was observed close to the haustorium, supporting the re-localization of this organelle upon pathogen attack (Figures 4A–E), as previously described (Schmelzer, 2002). As for the ER-luminal marker, HvSec61βa-GFP confirmed that the ER and EHM are in close proximity around the haustorial body. In summary, these confocal microscopy results suggest that the HvSec61βa-GFP-labeled ER is differentially recruited to the proximity of the EHM around the haustorial body, but not around the fingers.

FIGURE 4.

HvSec61βa-GFP localizes around the Bgh haustorial body. Confocal image of an epidermal cell, transformed with the HvSec61βa-GFP construct, taken 48 h after Bgh inoculation. (A–C) Three different focal planes from an image series of an infected cell with a haustorium. HvSec61βa-GFP localizes to the ER around the nucleus (arrow head, A) and surrounds the haustorium in an ER-like tubular pattern (asterisk, A). (C–E) GFP fluorescence (C), bright field (BF) (D) and merged image (E) show HvSec61βa-GFP localization at the surface of the haustorial body. HvSec61βa-GFP labels the tubular ER network, which is further illustrated in the 3D projection (F) (Image Surfer 1.2). Scale bar, 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

The fact that silencing of HvSec61βa causes the barley cells to become resistant to powdery mildew suggests that HvSec61βa either is a negative regulator of defense or a susceptibility factor required for disease. Sec61β is, as described above, associated with protein-transmitting pores in the ER. While it has been barely studied in plants, yeast data suggest that one of its activities is to be part of a post-translational translocon complex, but that this role is not essential under non-stressed conditions (Finke et al., 1996). Furthermore, Sec61β has also been associated with protein retrotranslocation from the ER (Kawaguchi and Ng, 2007; Nakatsukasa and Brodsky, 2008; Willer et al., 2008), and the question is, which of these activities is important in barley cells attacked by Bgh.

Silencing of HvSec61βa would result in inhibition of secretion if this protein is generally required for co- or post-translational protein translocation into the ER. This can hardly explain our phenotype, as inhibition of secretion in barley results in increased susceptibility to Bgh (Ostertag et al., 2013). A more likely explanation might be found in a specific HvSec61βa-function in post-translational translocation. This could involve the so-called “unfolded protein response” (UPR), which results from ER stress due to accumulation of unfolded proteins. During UPR, ER chaperones and components of the ERAD system are up-regulated to prevent the cell from undergoing programmed cell death (Travers et al., 2000). Similarly, ER stress induced by, e.g., tunicamycin (an N-glycosylation inhibitor) increases transcript levels of genes encoding proteins of the ER-QC machinery and the secretory pathway (Martinez and Chrispeels, 2003; Huttner and Strasser, 2012). Recently, a functional link has been established between UPR and pathogen defense in plants. Arabidopsis plants mutated in the IRE1a gene, encoding a key positive regulator of UPR, were found to have reduced resistance to bacteria (Moreno et al., 2012). An important chaperone that counter acts UPR is the ER- luminal protein, BiP, which is taken up post-translationally through the translocon complex in a Sec61β-dependent manner (Finke et al., 1996). Therefore, a model could be that HvSec61βa silencing causes ER-deprivation of BiP, in turn resulting in UPR as well as increased resistance. An Arabidopsis BiP knock-out line has previously been suggested to be prone for UPR. However, in disagreement with the model, the BiP knock-out line had reduced resistance (Wang et al., 2005). This may indirectly suggest that reduced BiP import into the ER is not the cause of the Sec61βa phenotype we observe, while Bgh resistance increases in this situation. We therefore favor a function for Sec61βa in protein retrotranslocation in the interaction with the powdery mildew fungus.

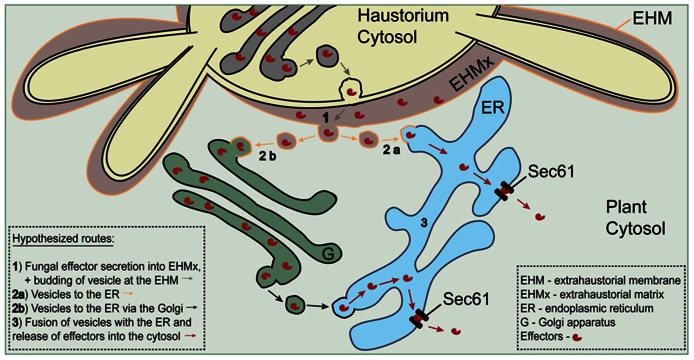

In the meantime, we had an indication of active recruitment of ER by the fungus, supporting that HvSec61βa functions as a susceptibility component. We observed a close association of the ER, labeled by HvSec61βa-GFP, and the Bgh haustorial body. The ER has also in other cases been found to be closely associated with haustoria (Koh et al., 2005; Micali et al., 2011). However, only Blumeria haustoria differentiate in two parts and provide a chance to distinguish variations in ER association. Interestingly, there is little ER association with the haustorial fingers, which could suggest that the ER proximity to the haustorial body is not due to ER being present wherever there is cytosol. Therefore, it is possible that the fungus controls the ER-haustorium association. Voegele et al. (2009) proposed that effector proteins are transferred to the cytosol via the ER. Effectors need to cross a membrane in order to reach the host cytosol, and the ER retrotranslocon pore offers an escape route for this. The resistance phenotype seen after HvSec61βa silencing is in agreement with a model, where this protein is necessary for pore function. As illustrated in Figure 5, we suggest that vesicle trafficking transfers the effectors from the EHMx to the ER in order for them subsequently to employ the retrotranslocon to enter the cytosol. While we consider the model in Figure 5 to describe the most likely mode of action of Sec61βa in plant powdery mildew interactions, other scenarios are possible. An unexpected function has for instance been described for Drosophila Sec61β, which is important for the secretion of the Gurken protein (Kelkar and Dobberstein, 2009). After silencing of Sec61β, Gurken left the ER as it normally did in control cells, but subsequently became stalled in the Golgi. Since a control protein still was observed to be secreted after silencing of Sec61β, this suggests that Sec61β is required for the Golgi-processing of a subset of the secreted proteins, including Gurken (Kelkar and Dobberstein, 2009). While this cannot be excluded to be due to a retrotranslocon defect, it may indicate that Sec61β also has a function in secretion, which is unrelated to the Sec61 protein pore. Future work will determine which function makes Sec61β important for plant’s susceptibility to the powdery mildew fungus, and whether modification of the gene can be exploited for a disease resistance purpose.

FIGURE 5.

Schematic model for a possible Sec61-dependent route of effector release into the host cytosol. Effectors are hypothesized to be transferred from the extrahaustorial matrix to the cytosol through Sec61 retrotranslocon pores in the ER. Trafficking from the matrix to the ER is envisaged to take place in vesicles dependent or independent of Golgi. Adapted from Voegele et al. (2009).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Patrick Schweizer for providing the pIPKTA30N vector, to Prof. Robert Dudler for providing the pBC17 construct and to Prof. Andreas Nebenführ for the 35S-SP-mCherry-HDEL construct. This work was supported by the Danish Strategic Research Council and The Faculty of Science, University of Copenhagen. Fluorescence imaging was performed using the facilities of the Center for Advanced Bioimaging (CAB) Denmark, University of Copenhagen.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- Blanke S. R. (2006). Portals and pathways: principles of bacterial toxin entry into host cells. Microbe 1 26–32 [Google Scholar]

- Bozkurt T. O., Schornack S., Banfield M. J., Kamoun S. (2012). Oomycetes, effectors, and all that jazz. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 15 483–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caillaud M. C., Piquerez S. J., Fabro G., Steinbrenner J., Ishaque N., Beynon J., et al. (2012). Subcellular localization of the Hpa RxLR effector repertoire identifies a tonoplast-associated protein HaRxL17 that confers enhanced plant susceptibility. Plant J. 69 252–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho P., Goder V., Rapoport T. A. (2006). Distinct ubiquitin-ligase complexes define convergent pathways for the degradation of ER proteins. Cell 126 361–373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho P., Stanley A. M., Rapoport T. A. (2010). Retrotranslocation of a misfolded luminal ER protein by the ubiquitin-ligase Hrd1p. Cell 143 579–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis M. D., Grossniklaus U. (2003). A gateway cloning vector set for high-throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Physiol. 133 462–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dash S., Van Hemert J., Hong L., Wise R. P., Dickerson J. A. (2012). PLEXdb: gene expression resources for plants and plant pathogens. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 D1194–D1201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng W., Nickle D. C., Learn G. H., Maust B., Mullins J. I. (2007). ViroBLAST: a stand-alone BLAST web server for flexible queries of multiple databases and user’s datasets. Bioinformatics 23 2334–2336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douchkov D., Nowara D., Zierold U., Schweizer P. (2005). A high-throughput gene-silencing system for the functional assessment of defense-related genes in barley epidermal cells. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 18 755–761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng D., Marshburn D., Jen D., Weinberg R. J., Taylor R. M., II, Burette A. (2007). Stepping into the third dimension. J. Neurosci. 27 12757–12760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finke K., Plath K., Panzner S., Prehn S., Rapoport T. A., Hartmann E., et al. (1996). A second trimeric complex containing homologs of the Sec61p complex functions in protein transport across the ER membrane of S. cerevisiae. EMBO J. 15 1482–1494 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gan P. H. P., Dodds P. N., Hardham A. R. (2012). “Plant infection by biotrophic fungal and oomycete pathogens,” in Signaling and Communication in Plant Symbiosis, Signaling and Communication in Plants Vol. 11 eds Perotto S., Baluska F. (Berlin: Springer-Verlag; ), 183–212 [Google Scholar]

- Gomord V., Denmat L. A., Fitchette-Laine A. C., Satiat-Jeunemaitre B., Hawes C., Faye L. (1997). The C-terminal HDEL sequence is sufficient for retention of secretory proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) but promotes vacuolar targeting of proteins that escape the ER. Plant J. 11 313–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerriero C. J., Brodsky J. L. (2012). The delicate balance between secreted protein folding and endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation in human physiology. Physiol. Rev. 92 537–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttner S., Strasser R. (2012). Endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation of glycoproteins in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 3:67 10.3389/fpls.2012.00067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi S., Ng D. T. (2007). SnapShot: ER-associated protein degradation pathways. Cell 129 1230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelkar A., Dobberstein B. (2009). Sec61beta, a subunit of the Sec61 protein translocation channel at the endoplasmic reticulum, is involved in the transport of Gurken to the plasma membrane. BMC Cell Biol. 10:11. 10.1186/1471-2121-10-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh S., Andre A., Edwards H., Ehrhardt D., Somerville S. (2005). Arabidopsis thaliana subcellular responses to compatible Erysiphe cichoracearum infections. Plant J. 44 516–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao H. J., Carpenter G. (2007). Role of the Sec61 translocon in EGF receptor trafficking to the nucleus and gene expression. Mol. Biol. Cell 18 1064–1072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez I. M., Chrispeels M. J. (2003). Genomic analysis of the unfolded protein response in Arabidopsis shows its connection to important cellular processes. Plant Cell 15 561–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer K. F., Waugh R., Brown J. W., Schulman A., Langridge P., Platzer M., et al. (2012). A physical, genetic and functional sequence assembly of the barley genome. Nature 491 711–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micali C. O., Neumann U., Grunewald D., Panstruga R, O’Connell R. (2011). Biogenesis of a specialized plant-fungal interface during host cell internalization of Golovinomyces orontii haustoria. Cell. Microbiol. 13 210–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno A. A., Mukhtar M. S., Blanco F., Boatwright J. L., Moreno I., Jordan M. R., et al. (2012). IRE1/bZIP60-mediated unfolded protein response plays distinct roles in plant immunity and abiotic stress responses. PLoS ONE 7:e31944 10.1371/journal.pone.0031944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsukasa K., Brodsky J. L. (2008). The recognition and retrotranslocation of misfolded proteins from the endoplasmic reticulum. Traffic 9 861–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson B. K., Cai X, Nebenführ A. (2007). A multicolored set of in vivo organelle markers for co-localization studies in Arabidopsis and other plants. Plant J. 51 1126–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostertag M., Stammler J., Douchkov D., Eichmann R., Huckelhoven R. (2013). The conserved oligomeric Golgi complex is involved in penetration resistance of barley to the barley powdery mildew fungus. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14 230–240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen C., van Themaat E. V., McGuffin L. J., Abbott J. C., Burgis T. A., Barton G., et al. (2012). Structure and evolution of barley powdery mildew effector candidates. BMC Genomics 13:694. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodighiero C., Tsai B., Rapoport T. A., Lencer W. I. (2002). Role of ubiquitination in retro-translocation of cholera toxin and escape of cytosolic degradation. EMBO Rep. 3 1222–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls M. M., Stein P. A., Taylor S. S., Ha E., McKeon F., Rapoport T. A. (1999). A visual screen of a GFP-fusion library identifies a new type of nuclear envelope membrane protein. J. Cell Biol. 146 29–44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders D. G., Win J., Cano L. M., Szabo L. J., Kamoun S., Raffaele S. (2012). Using hierarchical clustering of secreted protein families to classify and rank candidate effectors of rust fungi. PLoS ONE 7:e29847 10.1371/journal.pone.0029847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmelzer E. (2002). Cell polarization, a crucial process in fungal defence. Trends Plant Sci. 7 411–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz A., Herrgen H., Winkeler A., Herzog V. (2000). Cholera toxin is exported from microsomes by the Sec61p complex. J. Cell Biol. 148 1203–1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer P., Pokorny J., Schulze-Lefert P., Dudler R. (2000). Technical advance. Double-stranded RNA interferes with gene function at the single-cell level in cereals. Plant J. 24 895–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanu P. D., Abbott J. C., Amselem J., Burgis T. A., Soanes D. M., Stuber K., et al. (2010). Genome expansion and gene loss in powdery mildew fungi reveal tradeoffs in extreme parasitism. Science 330 1543–1546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto D., Jones D. A., Hardham A. R. (2003). GFP-tagging of cell components reveals the dynamics of subcellular re-organization in response to infection of Arabidopsis by oomycete pathogens. Plant J. 33 775–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teter K., Allyn R. L., Jobling M. G., Holmes R. K. (2002). Transfer of the cholera toxin A1 polypeptide from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol is a rapid process facilitated by the endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation pathway. Infect. Immun. 70 6166–6171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers K. J., Patil C. K., Wodicka L., Lockhart D. J., Weissman J. S., Walter P. (2000). Functional and genomic analyses reveal an essential coordination between the unfolded protein response and ER-associated degradation. Cell 101 249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg B., Clemons W. M., Jr., Collinson I., Modis Y., Hartmann E., Harrison S. C., et al. (2004). X-ray structure of a protein-conducting channel. Nature 427 36–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voegele R. T., Hahn M., Mendgen K. (2009). “The uredinales: cytology, biochemistry, and molecular biology,” in Plant Relationships, The Mycota V, ed. Deising H. (Berlin: Springer-Verlag; ) 69–98 [Google Scholar]

- Voeltz G. K., Prinz W. A., Shibata Y., Rist J. M., Rapoport T. A. (2006). A class of membrane proteins shaping the tubular endoplasmic reticulum. Cell 124 573–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D., Weaver N. D., Kesarwani M., Dong X. (2005). Induction of protein secretory pathway is required for systemic acquired resistance. Science 308 1036–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. N., Yamaguchi H., Huo L., Du Y., Lee H. J., Lee H. H., et al. (2010). The translocon Sec61beta localized in the inner nuclear membrane transports membrane-embedded EGF receptor to the nucleus. J. Biol. Chem. 285 38720–38729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whisson S. C., Boevink P. C., Moleleki L., Avrova A. O., Morales J. G., Gilroy E. M., et al. (2007). A translocation signal for delivery of oomycete effector proteins into host plant cells. Nature 450 115–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willer M., Forte G. M., Stirling C. J. (2008). Sec61p is required for ERAD-L: genetic dissection of the translocation and ERAD-L functions of Sec61P using novel derivatives of CPY. J. Biol. Chem. 283 33883–33888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X., Jantti J. (2009). Functional characterization of the trans-membrane domain interactions of the Sec61 protein translocation complex beta-subunit. BMC Cell Biol. 10:76 10.1186/1471-2121-10-76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann R., Eyrisch S., Ahmad M., Helms V. (2011). Protein translocation across the ER membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1808 912–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]