Abstract

We report a case of pseudoaneurysm of the anterior ascending branch of the left pulmonary artery, following a left upper lobectomy for pulmonary aspergillosis, for which we have done an endovascular treatment. This is the first case where complete pseudoaneurysm occlusion was accomplished after a transcatheter intra-aneurysmal N-butyl 2-cyanoacrylate (glue) injection.

Keywords: Pulmonary artery, Lobectomy, Pseudoaneurysm, Embolisation

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms are uncommon; most are caused by infections, like tuberculosis, vasculitis (Behçet's syndrome) or trauma, often iatrogenic; less common causes include pulmonary hypertension, congenital heart disease, lung carcinoma, and connective tissue disease (1-3). Because of potential risk of high mortality, secondary to pseudoaneurysm enlargement and rupture, prompt therapy is needed. We, hereby, describe a case of ascending branch of the left pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm, following a left upper lobectomy, for which a transcatheter endovascular embolisation of the aneurysm with intra-aneurysmal N-butyl 2-cyanoacrylate (glue) injection was performed.

CASE REPORT

A 30-year-lady had been presented to us 3 months ago with multiple episodes of hemoptysis and one major episode of 400 cc, and gave us a history of intermittent fever, cough, breathlessness and chest pain for a period of 2-3 months. She was a known case of pulmonary tuberculosis with left upper lobe fungal ball (pulmonary aspergillosis) for the past 7 years. She had had complete a course of Anti-tuberculosis therapy and was asymptomatic until this period when she was presented to us with hemoptysis. At this time, the left bronchial artery embolisation was done on an emergency basis. Her hemoptysis had stopped. She was started on anti-tuberculosis treatment and was discharged within a week. The patient visited an emergency department again a month ago for exacerbation of the above symptoms. Because of the recurrent symptoms and deteriorating pulmonary function test results, the left upper lobectomy for pulmonary aspergilloma was performed. The operation was carried out through a left posterolateral thoracotomy approach. The pulmonary artery was identified and branches to the upper lobe were ligated. The pulmonary vein was dissected and the superior pulmonary vein was ligated and stapled. The respective bronchus was dissected and the upper lobe was resected. The inferior pulmonary ligament was excised in order to enable the lower lobe to occupy the entire left thoracic cavity.

The early postoperative period was uneventful. In the third post-operative week, she started having streaky hemoptysis. Fibre optic bronchoscopy detected a normal tracheobronchial tree, however, the left upper lobe surgical closure site was congested and inflamed. Though the white blood cell count was normal, the patient was treated for a presumed chest infection. The patient had spotty hemoptysis for the next two weeks, until she developed 2-3 episodes of massive hemoptysis of about 400-500 cc of blood. Patient was intubated and emergency computed tomography (CT) pulmonary angiography was done, which revealed a large pseudoaneurysm of the ascending branch of the left pulmonary artery (Fig. 1A, B). Because of the patient's severe pulmonary insufficiency, she was not a surgical candidate and was referred to us for endovascular embolisation.

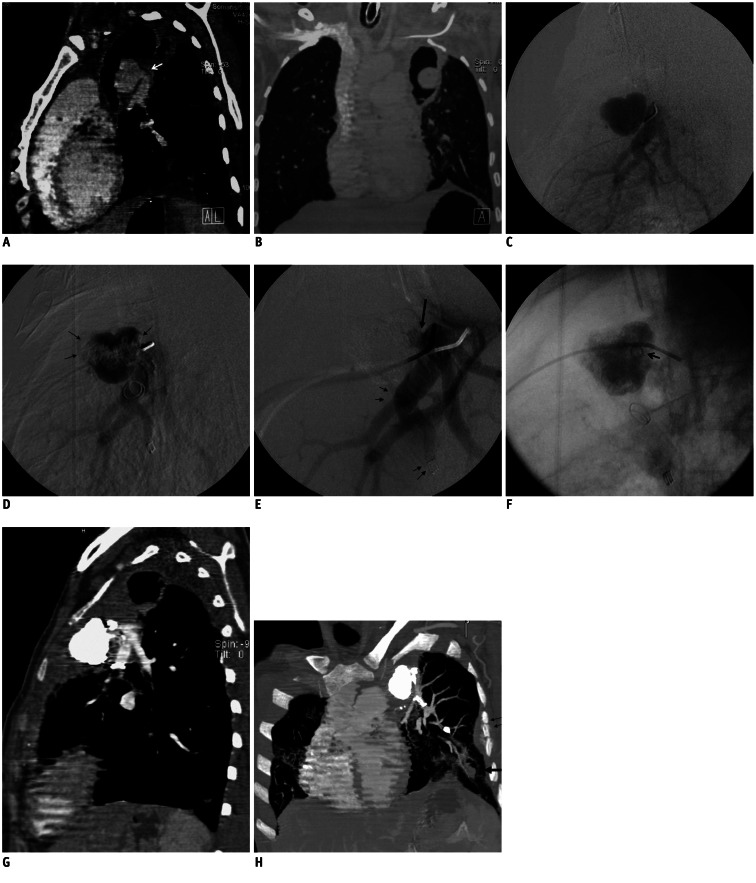

Fig. 1.

30-years lady with pulmonary artery aneurysm.

A. Preembolization sagittal multiplanar reconstruction (MPR) CT image of pulmonary angiography shows PAA arising from anterior ascending branch of left pulmonary artery. Note small and wide neck (white arrow) of feeding branch. B. Oblique coronal MPR CT image (lung windows) shows round soft tissue mass (PAP) projecting into left upper chest pneumothorax. C. Pulmonary angiography (lateral view) shows approximately 2.8 cm heart shaped aneurysm from anterior ascending branch. D. Check angiogram, post glue (75%) embolisation, shows residual filling of aneurysm. Irregular band shaped filling defect seen within central part of PAP is due to solidified glue (black arrows). E. Post glue (50%) embolisation angiogram shows complete obliteration of aneurysm. Feeding artery is seen to be patent (long black arrow). Note displaced coils (small black arrows) in lower lobe branches. There is no occlusion to flow of blood in these lower lobe branches. F. Post embolisation, spot film shows glue cast filling entire PAP. Note migrated coil within aneurysm sac (black arrow). Coils in lower lobe branches are also seen. G. Sagittal MPR of CT pulmonary angiography at 2 months interval shows glue cast in aneurysm. There is no filling of aneurysm. Pneumothorax seen previously is partially resolved now. H. Oblique coronal MPR CT image shows lower lobe arteries with coils in their lumen being opacified. New aspergilloma is seen in lateral basal segment of left lobe (black arrow) and rib osteomyelitis (small black arrows).

Under local anesthesia, with anesthetists standing by for emergency resuscitation if need arise, pulmonary angiography with 5 Fr, 110-cm pigtail catheter (Cordis, Johnson & Johnson, New Jersey) was introduced via the right femoral venous approach, which showed approximately 3.5 cm aneurysm arising from the ascending branch of the left pulmonary artery, shortly after its origin (Fig. 1C). Then, a 5 Fr, 100-cm head hunter catheter (Cordis, Johnson & Johnson, New Jersey) was introduced into the feeding artery of the aneurysm, just short of the aneurysm sac. Initially, we tried to occlude the feeding vessel with 35-5-5 and 35-8-8 coils (COOK, Bloomington, IN, USA), but both of these coils got misplaced proximally in the lateral basal and lower lobe trunk arteries, respectively. Because of larger diameter of the coils than the caliber of these arteries, the misplaced coils got stuck in a proximal part of the arteries. On an angiogram, we could see the uninterrupted rapid blood flow through the coils to the lower branches.

Further, with digital road mapping, 5 Fr head hunter catheter in the feeding artery, and acting as a guiding catheter, the aneurysm sac was catheterized with a 2.7 Fr microcatheter (Terumo Progreat; Terumo Deutschland GmbH, Germary). Now we decided to occlude the aneurismal sac by completely filling the sac with N-butyl 2-cyanoacrylate (glue) injection. We calculated the volume of the glue mixture required in order to fill the aneurysm cavity by slowly calculating the volume of contrast injected, without causing the reflux of the contrast into the normal pulmonary circulation proximally. The dead volume of the microcatheter was taken into consideration. In this manner, the volume required was approximately 4 cc. To prevent a reflux, 5 cc of higher concentration i.e. 75% glue mixture of Histoacryl (Braun, Melsungen, Germany) and iodized oil (Lipiodol, Andre Guerbert, Aulnay sous Bois, France) was taken in a 5-mL Luer-Lock syringe, however we could only inject approximately 1.5 cc of the glue, as the microcatheter got blocked. The catheter was removed with a jerk. Catheter sticking or breakage did not occur during the process of catheter retrieval and was immediately flushed vigorously with 5% dextrose to reopen the lumen. Check angiogram showed the glue cast in the central part of the aneurysm sac with aneurysm still filling in the periphery (Fig. 1D). We now attempted to occlude the feeding artery with coil, but this time, the coil got dislodged in the aneurysmal sac. Now, the angiographic picture was much clearer, and on correlating with CT saggital reconstructed images, we got to know that the length of the feeding artery to the pulmonary artery aneurysm (PAP) sac was very short. So now, not to compromise the pulmonary circulation, we did not have any other option except to fill the sac either with coils or liquid materials. In order to be economical on the cost, as well as our past experience with the glue, we decided to occlude PAP with intra-aneurysmal injection of the glue. We introduced the previously used microcatheter into the sac, and this time, we used 50% glue mixture and were able to fill the sac completely with calculated volume of 3 cc of liquid mixture without spillage into the proximal normal circulation. Post embolisation check angiogram showed a complete obliteration of the aneurysm sac with anterior ascending branch, and other branches of the left pulmonary artery being patent (Fig. 1E, F). There was no alteration in the blood flow through the coils into the lower lobe branches, and therefore, we did not try to retrieve the coils.

The post procedure period was marked by streaky hemoptysis for 3 days. CT performed on the 6th day showed glue cast with no filling of the aneurysm. She was discharged on the 10th post-procedure day on antituberculous treatment. However, after being asymptomatic for 2 months, she presented again to our hospital with a single episode of 300 cc of hemoptysis. Emergency CT was performed, which did not show the new aneurysm or refilling of the previously embolised aneurysm (Fig. 1G); however, at this time, we could see a new aspergilloma in lateral basal segment of the lower lobe, and rib osteomyelitis (Fig. 1H). At present, she is still admitted and is on a conservative management and being further investigated for these new CT findings.

DISCUSSION

Pulmonary artery aneurysms and pseudoaneurysms (PAPs) are rare; most are caused by infections, like tuberculosis, vasculitis (Behçet's syndrome) or trauma, often iatrogenic, especially after Swan Ganz catheter insertion; and less common causes include pulmonary hypertension, congenital heart disease, lung carcinoma, and connective tissue disease (1-3). Thus, any destructive process of the lung, whatever its pathogenesis, can erode the vessels in its vicinity, be it a pulmonary or systemic vessel. The etiology in this case can be attributed to inadvertent insult to the pulmonary artery during surgery for pulmonary aspergilloma. Also, after lobectomy, significant increase in the pulmonary vascular resistance index has been described in the literature (4), and this could have had a possible contributory role for the development of the pseudoaneurysm. Another cause could be a low grade infection of the already weakened upper lobe pulmonary arterial wall, though the blood investigations were normal in our patient.

The most common cause for intrapulmonary bleedings is the hemoptysis, due to bronchial artery erosion seen in as many as 95% of all cases. In contrast, bleeding from the pulmonary arteries is very rare, usually massive, accounting for less than 5% of all cases (5), and is usually due to pseudoaneurysm rupture.

Because of the risk of PAP enlargement and rupture, which leads to death in approximately 50% of patients, prompt therapy is required. The available treatment modalities for PAP are medical therapy, surgery and percutaneous catheter embolisation of the pseudoaneurysm. Medical treatment by the means of immunosuppressive drugs and steroids has been found to cure or decrease the size of aneurysms in Behcets disease (6, 7).

Several surgical techniques, such as lobectomy, pneumonectomy, hilar clamping with direct arterial repair and ligation, have been used. However, in our case, due to the patient's severe pulmonary insufficiency, she was not a surgical candidate.

Endovascular embolisation carries a lower rate of morbidity and mortality than the surgical resection. There are number of reports in the literature addressing the treatment of PAPs-most of them using metallic coils (8) or silicon balloon (9) to occlude the arterial feeders. These placements can also occlude the perfusion to aerated lung, distal to the embolisation site, and are associated with complications, like coil migration and damage to vessel wall. Other authors have occluded the PAP by intraneurysmal placement of coils (10); however it carries a potential risk of mass effect and aneurysm rupture. Still, other authors have described the use of covered stents (11), and recently, Hovis and Zeni (12) have used thrombin percutaneously for the PAA refractory to coil the embolisation. In our case, initially, we attempted unsuccessfully to occlude the feeding artery with the coils. However, the coils migrated proximally to enter into the lower lobe circulation without compromising the blood circulation to these segments. We later realized that this was due to a short length and wide neck of the feeding artery, that we were not able to keep the catheter stable in this branch. We did not want to occlude the aneurysmal sac with coils, firstly because of the large size of the lesion, use of multiple coils could result in a mass effect after embolisation, and secondly it would have been very expensive; also it might be further complicated by coil migration, resulting from the wide neck of the aneurysm. In our case, because of regular and comfortable experience at tackling abdominal visceral aneurysms with glue embolization, we decided to use this liquid material as embolic material. Cil et al. (7) embolised the feeding branch to PAA, using the glue with a "bubble technique"; however, this was not possible in our case because of the short length in the feeding artery. Therefore, we considered the alternative option of intraaneurysmal injection of liquid embolic (glue).

Glue (N-butyl 2-cyanoacrylate) is a rapidly hardening liquid adhesive, and has been used as an effective embolic agent for brain vascular malformations; however, necessity of operator experience with the use of liquid embolic material is a major limitation in its application to aneurysms. There are some studies showing the feasibility of intraaneurysmal injection of the glue in intracranial aneurysms (13), thereby keeping the antegrade flow in the aneurysm bearing artery patent. We report the first case, in which the N-butyl 2-cyanoacrylate was successfully injected, intraaneurysmally, through the transcatheter route for the occlusion of a pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm, after an upper lobe lobectomy for aspergillosis. Glue offers the advantage of permanent occlusion of the vessel, and because of its low viscosity, it can be injected through a microcatheter into small and tortuous arteries. It is admixed with ethiodized oil in various ratios to achieve radiopacity and to adjust the polymerization time allowing for more controlled embolisation. The use of higher concentrations of glue results in quicker solidification; however, on the contrary, the longer the polymerization time, the greater the risk of non-target embolisation because there is the possibility of embolic material being washed away before it solidifies. In our case we initially used 75% glue to prevent the reflux into the parent artery; however there was early polymerisation of the glue with the sac preventing an evenly distribution. Therefore, we had to dilute the glue to make it 50% concentration, and this time, there was complete filling of the aneurysm.

In conclusion intraaneurysmal injection of the liquid embolic materials is feasible, safe, and effective trancatheter treatment option for pulmonary artery aneurysms and is possibly not associated with the risk of rupture seen with packing of aneurysms with coils. However, appropriate concentration of the glue, long term results, and etc. will require further experience to confirm its safety and efficacy in pulmonary circulation.

References

- 1.Picard C, Parrot A, Boussaud V, Lavolé A, Saidi F, Mayaud C, et al. Massive hemoptysis due to Rasmussen aneurysm: detection with helicoidal CT angiography and successful steel coil embolization. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1837–1839. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1912-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferretti GR, Thony F, Link KM, Durand M, Wollschläger K, Blin D, et al. False aneurysm of the pulmonary artery induced by a Swan-Ganz catheter: clinical presentation and radiologic management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1996;167:941–945. doi: 10.2214/ajr.167.4.8819388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantasdemir M, Kantarci F, Mihmanli I, Akman C, Numan F, Islak C, et al. Emergency endovascular management of pulmonary artery aneurysms in Behçet's disease: report of two cases and a review of the literature. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2002;25:533–537. doi: 10.1007/s00270-002-1967-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haniuda M, Kubo K, Fujimoto K, Aoki T, Yamanda T, Amano J. Different effects of lung volume reduction surgery and lobectomy on pulmonary circulation. Ann Surg. 2000;231:119–125. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200001000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffmann RT, Spelsberg F, Reiser MF. Lung bleeding caused by tumoral infiltration into the pulmonary artery--minimally invasive repair using microcoils. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:1282–1285. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9130-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tunaci M, Ozkorkmaz B, Tunaci A, Gül A, Engin G, Acunaş B. CT findings of pulmonary artery aneurysms during treatment for Behçet's disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:729–733. doi: 10.2214/ajr.172.3.10063870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cil BE, Geyik S, Akmangit I, Cekirge S, Besbas N, Balkanci F. Embolization of a giant pulmonary artery aneurysm from Behcet disease with use of cyanoacrylate and the "bubble technique". J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16:1545–1549. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000171692.61294.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deshmukh H, Rathod KK, Garg A, Sheth R. Ruptured mycotic pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm in an infant: transcatheter embolization and CT assessment. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2003;26:485–487. doi: 10.1007/s00270-003-0073-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Renie WA, Rodeheffer RJ, Mitchell S, Balke WC, White AI., Jr Balloon embolization of a mycotic pulmonary artery aneurysm. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1982;126:1107–1110. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1982.126.6.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidoff AB, Udoff EJ, Schonfeld SA. Intraaneurysmal embolization of a pulmonary artery aneurysm for control of hemoptysis. AJR. 1984;142:1019–1020. doi: 10.2214/ajr.142.5.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park A, Cwikiel W. Endovascular treatment of a pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm with a stent graft: report of two cases. Acta Radiol. 2007;48:45–47. doi: 10.1080/02841850601045104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hovis CL, Zeni PT., Jr Percutaneous thrombin injection of a pulmonary artery pseudoaneurysm refractory to coil embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:1943–1946. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000250985.07237.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suh DC, Kim KS, Lim SM, Shi HB, Choi CG, Lee HK, et al. Technical feasibility of embolizing aneurysms with glue (N-butyl 2-cyanoacrylate): experimental study in rabbits. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:1532–1539. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]