Abstract

Meningeal melanocytoma is a rare benign tumor with relatively good prognosis. However, local aggressive behavior of meningeal melanocytoma has been reported, especially in cases of incomplete surgical resection. Malignant transformation was raised as possible cause by prior reports to explain this phenomenon. We present an unusual case of meningeal melanocytoma associated with histologically benign leptomeningeal spread and its subsequent aggressive clinical course, and describe its radiological findings.

Keywords: Spine, Magnetic resonance imaging, Meninges, Neoplasm, Melanocytoma

INTRODUCTION

Meningeal melanocytoma is a rare tumor arising from leptomeningeal melanocytes. Meningeal melanocytoma is thought to fall at the benign end of a continuous spectrum of neoplastic leptomeningeal melanocyte proliferations that includes primary malignant melanoma at the opposite end from which they differ in behavior and aggressiveness. Meningeal melanocytoma has a much better prognosis than its malignant counterparts (1). Although rare, local recurrence or leptomeningeal spread of meningeal melanocytoma secondary to malignant transformation has been reported years after the initial diagnosis (2-4). In a literature review, there was only one case report of a meningeal melanocytoma causing a diffuse benign leptomeningeal spread. However, the histologically benign nature of leptomeningeal spread was confirmed by analysis of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), not by pathological examination of a surgical specimen, in a prior report (5). Here, we present an unusual case of a meningeal melanocytoma with benign leptomeningeal spread, resulting in fatal clinical course.

CASE REPORT

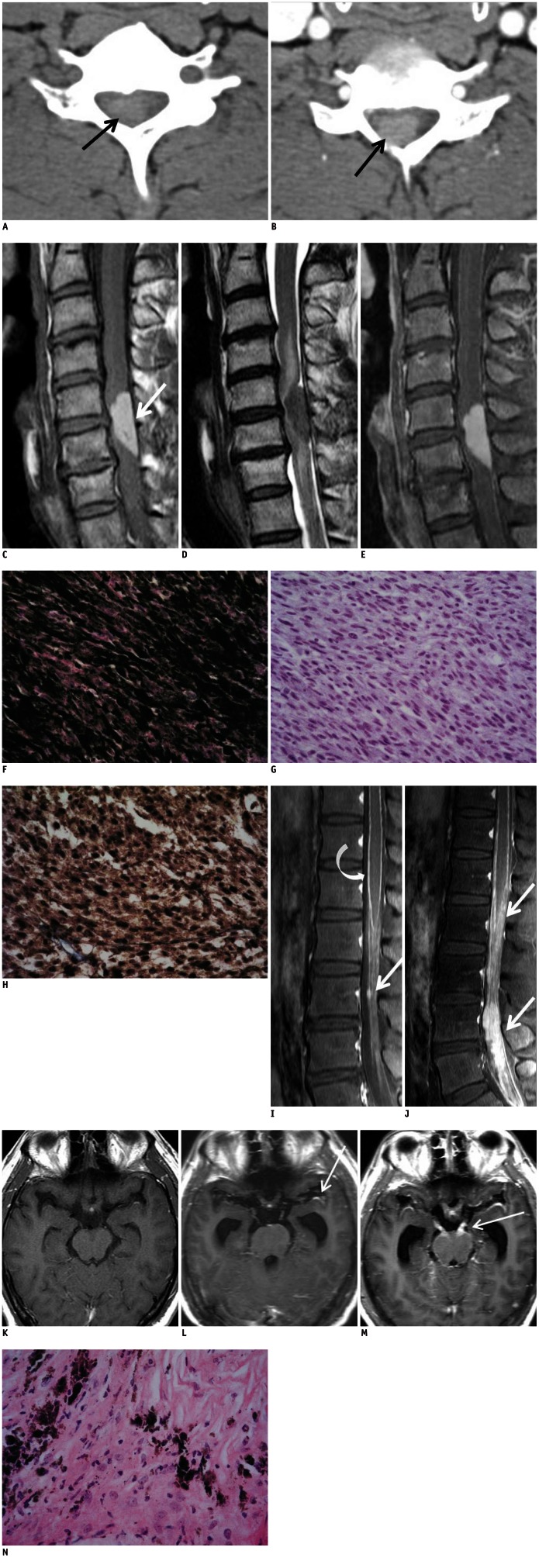

A 37-year-old previously healthy man presented with a 2 months history of increasing posterior neck pain and radiating pain to the right upper extremity. Neurological examination showed weakness, numbness and a tingling sensation in the right arm. The remainder of his neurological and physical examination was unremarkable. In particular, examinations of the skin and the fundus of the eye did not reveal any melanotic lesions. Cervial spinal computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a well-defined highly enhanced right-sided intra-spinal soft tissue mass that was homogeneously hyperdense on precontrast CT scan at the C5-C6 level (Fig. 1A, B). Cervial spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed that an intradural extramedullary mass was displacing the spinal cord to the left and was hyperintense on T1-weighted image (T1WI) and hypointense on T2-weighted image (T2WI). Although contrast enhancement of the mass was not evidently revealed by visual assessment due to strong T1 hyperintensity of the mass on unenhanced images, mild diffuse enhancement of the tumor was verified by the quantitative measurement of the signal intensity. The spinal cord was severely displaced and compressed by the mass and was associated with intramedullary signal changes on T2WI, indicating compressive myelopathy (Fig. 1C, D, E). The patient underwent C5-C6 cervical laminectomy, durotomy and excision of the soft black intradural mass. A subtotal resection was achieved. Some small fragments of the tumor could not be dissected because of adhesion to the spinal cord. Microscopically, the tumor was composed of heavily pigmented spindle cells (Fig. 1F). Because a large amounts of melanin pigment obscured cell detail, bleaching of the melanin pigment was performed. Depigmented sections showed a uniform appearance of spindle cells with inconspicuous nucleolus (Fig. 1G). Neither necrosis nor mitotic figures were identified, essentially excluding the possibility of a malignant neoplasm. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were positive for S-100 protein (Fig. 1H) and HMB-45, supporting their differentiation toward melanocytes. Ki-67 was expressed in less than 1% of tumor cells, suggesting a low proliferation rate of the tumor. These histopathologic features and immunohistochemical results were consistent with the characteristics of a benign melanocytic neoplasm, thus the tumor was diagnosed as a melanocytoma. The patient's symptoms were postoperatively improved.

Fig. 1.

Cervical meningeal melanocytoma with benign leptomeningeal spread in 37-year-old man.

Cervical spinal meningeal melanocytoma in 37-year-old man. A. Non-enhanced cervical spinal CT image shows well-defined intraspinal mass (arrow) being hyperdense in relation to muscular tissue. B. Contrast-enhanced CT image shows homogeneously contrast enhancing intraspinal mass (arrow). C. Sagittal T1-weighted MR image reveals mass having homogeneous high signal intensity, which is consistent with T1-shortening effect of melanin (arrow). D. On sagittal T2-weighted image, majority of mass reveals low signal intensity and intradural extramedullary location at C5-C6. Compressed spinal cord shows intramedullary high signal intensity. E. After administration of contrast media, enhanced T1-weighted image (T1WI) shows homogeneous and strong hyperintensity of tumor. Visual assessment of degree of tumoral contrast enhancement is limited due to strong T1 hyperintensity of mass on unenhanced T1WI. Photomicrographs of cervical spinal meningeal melanocytoma from 37-year-old man. F. Microscopic examination shows tumor cells containing large amounts of melanin pigment and consequentially obscuring details of cells (H&E stain, × 400). G. After melanin bleaching, spindle cells with minimal cytologic atypia are seen (H&E stain, × 400). H. Immunohistochemical exmination shows tumor cells stained strongly positive for S-100 protein (× 400). Postoperative lumbar spinal MR images. I. Initial thoracolumbar MRI (2 weeks after first operation). Sagittal fat suppressed gadolinium enhanced T1-weighted image (T1WI) shows diffuse leptomeningeal enhancements (curved arrow) and small enhancing nodules (arrow) in cauda equina suggesting leptomeningeal spread. J. Repeated lumbar MRI (5 weeks after first operation). Sagittal fat suppressed gadolinium enhanced T1WI shows markedly extensive intraspinal masses with diffuse contrast enhancements in lumbosacral region (arrows). Postoperative brain MR images. K. Initial brain MRI (2 weeks after first operation). Axial fat supressed gadolinium enhanced T1-weighted image (T1WI) reveals no abnormal intracranial contrast enhancement or Hydrocephalus. L. Repeated brain MRI (4 weeks after first operation). Axial fat suppressed gadolinium enhanced T1WI shows newly developed hydrocephalus with mild leptomeningeal enhancements along cranial surface including left sylvian fissure (arrow), representing leptomeningeal seeding. M. Follow-up brain MRI (7 weeks after first operation). Axial fat suppressed gadolinium enhanced T1WI shows persistent hydrocephalus with diffuse leptomeningeal enhancements along cranial surfaces, brainstem and intracranial cranial nerves (arrow). N. Photomicragraph of surgical specimen of leptomeningeal seeding mass shows that mass is composed of histologically benign cells (H&E stain, × 400).

However, 2 weeks postoperatively, the patient newly developed lower back pain. Thoracolumbar spinal MR study revealed diffuse leptomeningeal enhancement and intradural small enhancing nodules that were hyperintense on T1WI in the lumbosacral region, indicating leptomeningeal seeding (Fig. 1I). Unfortunately, it was uncertain whether the lumbosacral lesions had been presented preoperatively or were newly developed postoperatively because preoperative thoracolumbar evaluation had not been performed. Adjuvant radiotherapy was planned. Whole spinal PET-CT showed only a small focal uptake corresponding to the largest lumbar leptomeningeal nodule on the MRI. There was no uptake in the spinal region including the cervical operative site. Brain MRI was performed to exclude cranial lesion before starting radiotherapy. There was no hydrocephalus nor any other abnormal findings (Fig. 1K). The patient underwent postoperative whole spinal radiotherapy. Four weeks postoperatively, the patient presented headache, nausea and vomiting while receiving radiotherapy. Repeated brain MRI revealed newly developed hydrocephalus with subtle leptomeningeal enhancements especially in the base of the brain, indicating obstructive hydrocephalus secondary to leptomeningeal seeding (Fig. 1L). A ventriculoperitoneal shunt procedure was performed. Repeated lumbar spinal MRI performed 5 weeks postoperatively revealed an aggravated leptomeningeal mass occupying most of the lumbosacral spinal canal (Fig. 1J). Decompressive lumbar laminectomy and partial removal of the leptomeningeal spreading mass were achieved. Microscopically, no evidence of malignant transformation was revealed (Fig. 1N). Two weeks after the lumbar spinal operation, a follow-up brain MRI revealed persistent hydrocephalus associated with diffuse enhancing intracranial leptomeningeal masses in the cranial nerves, the brainstem, and the brain (Fig. 1M). The disease advanced and the patient expired, months after the initial diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

Melanocytes are neural crest-derived cells in origin which are normally found in the leptomeninges. They are most highly concentrated on the surfaces of the base of brain, brain stem, and upper cervical spinal cord. These melanocytes may cause primary melanocytic neoplasms including malignant melanoma, meningeal melanocytoma and diffuse melanosis. Primary melanocytic neoplasms are rare and are usually malignant, with about 25% of them being associated with neurocutaneous melanosis syndrome. Meningeal melanocytoma is at the benign end of the spectrum of primary melanotic neoplasms, and is less common than its malignant counterpart, meningeal melanoma (1, 5). In 1972, Meningeal melanocytoma was first introduced by Limas and Tio as a primary melanocytic lesion from the leptomeninges with benign clinical and pathologic features (6). They may occur in the spine or the brain. Meningeal melanocytomas are commonly seen in the cervical region of the spinal canal. Lesions may also arise in the thoracic or lumbar region, most often located in the intradural extramedullary compartment (7).

On CT scans, meningeal melanocytomas constantly appear as well-circumscribed, isodense to hyperdense tumors that are homogeneously enhanced by administration of contrast media. The tumors are isointense to hyperintense on T1WI and hypointense on T2WI of MRI. These variances in MR signal intensities are most likely related to the degree of melanin content; the more melanin, the more shortening of the T1, T2 relaxation times. Paramagnetic free radicals known to exist in melanin are thought to be responsible for the associated T1 and T2 shortenings by the proton-electron dipole-dipole proton relaxation enhancement mechanism (8). Meningeal melanocytomas are uniformly enhanced with contrast media injection and may show blooming of low signals related to the melanin susceptibility effect on gradient MRI (1, 5, 8). It may be difficult to recognize whether a melanocystic neoplasm is contrast enhanced or not on MRI because of the pre-contrast T1-high signal intensity of the mass (Fig. 1A, C). In the present case, the homogeneous contrast enhancement of the tumor was recognized on contrast enhanced CT images.

The differential diagnosis of melanocytic neoplasms includes high cellular tumors, i.e., meningioma, lymphoma and some metastasis, that are homogeneously isodense to hyperdense on pre-contrast CT scan and are homogeneously enhanced after contrast administration. The typical MRI findings of these high cellular tumors are described to be isointense to the cord on T1WI, isointense to the cord on T2WI and intensely enhanced after contrast administration. Thus, MRI can help with the differential diagnosis. However, MRI is not always helpful due to the variant signal intensity of melanocytic neoplasms depending on their melanin content. Tumor calcification and hyperostosis of adjacent bones have rarely been described in melanocytic melanomas. Nevertheless, a lack of these signs obviously does not exclude the presence of a meningioma. Another differential diagnosis is schwannoma, especially a small one. Small schwannomas usually show uniform contrast enhancement, whereas larger schwannomas may be heterogeneous (9). Early subacute hematomas also may have a similar appearance to melanocytic neoplasms on MRI. However, post-contrast CT scans show conspicuous contrast enhancement in the mass and is helpful to differentiate melanocytic melanoma from subacute hematoma. Primary pigmented neoplasms of the central nervous system (CNS) includes meningeal melanocytoma, malignant melanoma, melanotic meningioma and melanotic schwannoma. Radiologically, the differential diagnosis of these primary pigmented CNS tumors is extremely difficult owing to their similar appearances on CT and MR studies, thus necessitating additional diagnostic confirmation through electron microscopy and immunohistochemical analysis. Furthermore, since the biological behavior, treatment, and prognosis of these lesions are different, it is important to make the correct pathologic diagnosis.

On gross examination, most meningeal melanocytomas appear dark brown to black as a result of abundant melanin production. Microscopically, meningeal melanocytomas feature variably pigmented spindle cells growing in tight nests. Individual tumor cells are cytologically bland with little pleomorphism and indistinct nucleoli. First of all, meningeal melanocytoma must be distinguished from malignant melanoma, because both are of same origin; melanocyte. Features in favor of malignant melanoma include tumor necrosis, cytologic atypia and high mitotic activities. Making the distinction from melanotic meningioma is also important. A positive immunostain for epithelial membrane antibody can confirm the diagnosis of melanotic meningioma. On the other hand, melanocytomas are typically immunoreactive for S-100 protein and HMB-45. Melanotic schwannomas show considerable histologic overlap with melanocytomas, and both tumors are immunoreactive for S-100 protein, therefore making the distinction between these tumors difficult. However, immunohistochemical staining for HMB-45 to detect the melanocytic origin can help to reach an accurate diagnosis. Electron microscopy can also be utilized to demonstrate basal lamina deposits around individual schwann cells or melanosomes in melanocytes (9).

Complete surgical resection can be curative. Although total resection is recommended, hypervascularity, extensive large size and unfavorable location of the tumor may preclude complete resection. The role and efficacy of radiotherapy, which is used for both residual and recurrent tumors, remains unclear in meningeal melanocytoma. Long-term survival of patients who underwent subtotal resection of the tumor with and without radiotherapy has been reported. The results explain the need to individualize the use of postoperative radiotherapy and suggest that it may be prudent to reserve its use for those patients with symptomatically residual, progressive, or recurrent tumors not amenable to further resection (2, 10).

The prognosis for patients with meningeal melanocytoma is relatively good, with most patients surviving at least several years after the diagnosis. However, local recurrence and leptomeningeal spread have been rarely reported to occur late in the course of meningeal melanocytoma as a result of malignant transformation, especially in cases of subtotal gross resection (2-4). A literature review revealed only one report of meningeal melanocytoma associated with benign leptomeningeal spread and critical clinical course. Malignant transformation for leptomeningeal spread was excluded by CSF analysis in a prior report (5). However, in our case, benign leptomeningeal spread from meningeal melanocytoma was proven through a histological study of the patient's surgical specimen (Fig. 1N). Although there is a possibility that the initial lumbar leptomeningeal lesion could still present multiple primary lesions, the fact that they were rapidly grown on the repeat lumbar MR study and unremarkable findings on the initial brain MRI makes it unlikely.

In summary, besides meningeal melanoma, and other primary pigmented CNS tumors such as melanotic schwannoma and melanotic meningioma, meningeal melanocytoma must be considered when one encounters a meningeal based mass showing isointensity to hyperintensity on T1WI, hypointensity on T2WI, and homogeneous enhancement after contrast administration. Additionally, although extremely rare, meningeal melanocytoma may be associated with histological benign leptomeningeal spread and aggressive clinical course in spite of the absence of malignant transformation. Making a correct differential diagnosis and being alert to the unusual behavior of meningeal melanocytoma will be helpful in managing the patient appropriately.

References

- 1.Painter TJ, Chaljub G, Sethi R, Singh H, Gelman B. Intracranial and intraspinal meningeal melanocytosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1349–1353. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roser F, Nakamura M, Brandis A, Hans V, Vorkapic P, Samii M. Transition from meningeal melanocytoma to primary cerebral melanoma. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:528–531. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.101.3.0528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang F, Li X, Chen L, Pu X. Malignant transformation of spinal meningeal melanocytoma. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;6:451–454. doi: 10.3171/spi.2007.6.5.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Uozumi Y, Kawano T, Kawaguchi T, Kaneko Y, Ooasa T, Ogasawara S, et al. Malignant transformation of meningeal melanocytoma: a case report. Brain Tumor Pathol. 2003;20:21–25. doi: 10.1007/BF02478943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bydon A, Gutierrez JA, Mahmood A. Meningeal melanocytoma: an aggressive course for a benign tumor. J Neurooncol. 2003;64:259–263. doi: 10.1023/a:1025628802228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Limas C, Tio FO. Meningeal melanocytoma ("melanotic meningioma"). Its melanocytic origin as revealed by electron microscopy. Cancer. 1972;30:1286–1294. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197211)30:5<1286::aid-cncr2820300522>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chacko G, Rajshekhar V. Thoracic intramedullary melanocytoma with long-term follow-up. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:589–592. doi: 10.3171/SPI.2008.9.08323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen CJ, Hsu YI, Ho YS, Hsu YH, Wang LJ, Wong YC. Intracranial meningeal melanocytoma: CT and MRI. Neuroradiology. 1997;39:811–814. doi: 10.1007/s002340050510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brat DJ. Melanocytic Neoplasm of Central Nerveous System. In: Perry A, Brat DJ, editors. Practical Surgical Neuropathology: A Diagnostic Approach. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2010. pp. 353–359. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clarke DB, Leblanc R, Bertrand G, Quartey GR, Snipes GJ. Meningeal melanocytoma. Report of a case and a historical comparison. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:116–121. doi: 10.3171/jns.1998.88.1.0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]