Introduction

Pancreatic duct stent placement during Whipple procedure is considered a common and relatively safe practice to maintain the patency of pancreatico-enteric anastomosis. Potential complications include retained stents or migration of the pancreatic stent into the biliary system.

Case

A 52-year-old Caucasian female was referred to our facility for recurrent episodes of post-prandial right upper quadrant abdominal pain. This was associated with a 12 pound weight loss over a period of one year. Her past medical history was significant for duodenum adenocarcinoma treated with a Whipple procedure two years prior. A pancreatic stent was placed at the pancreatico-enteric anastomosis during the surgery. She is a former smoker, denies use of alcohol or any other recreational drugs. Her medications include omeprazole and Naproxen. Her vital signs were normal. Abdominal examination revealed right upper quadrant tenderness with no guarding or rebound. The rest of her examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory studies revealed a white cell count of 6.4×1000 /mm3, hemoglobin of 14 g/dL, platelets of 260×1000 /mm3, amylase 27 U/L, lipase 12 U/L, total bilirubin 2.1 mg/dL, albumin 4.5 g/dL, alkaline phosphatase 116 U/L, AST 22U/L and ALT of 18 U/L. Abdominal ultrasound was unremarkable. A CT scan of the abdomen was ordered due to her previous history of duodenal malignancy which revealed dilated biliary tree with a small stent lodged in the common bile duct (CBD) through choledochoduodenostomy site. There was no evidence of mass lesion at the surgery site or abdominal lymphadenopathy. The patient was referred to our institution for ERCP to evaluate the biliary tree and retrieve the migrated pancreatic stent.

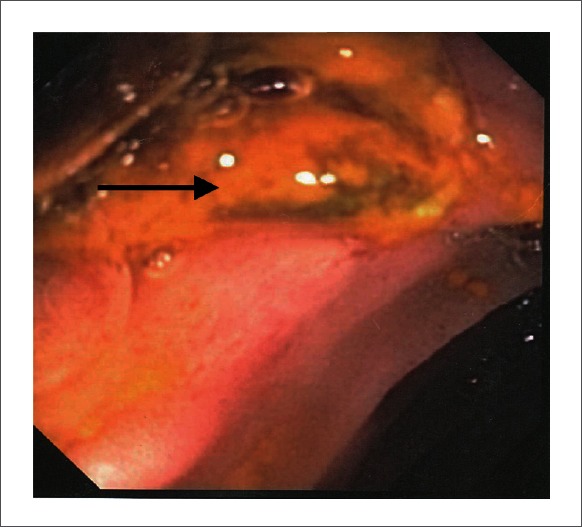

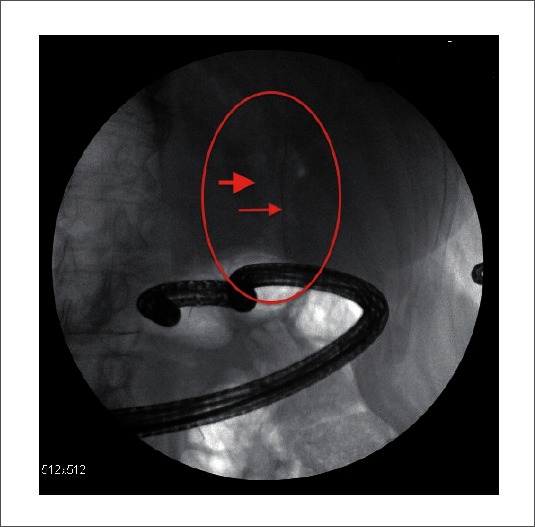

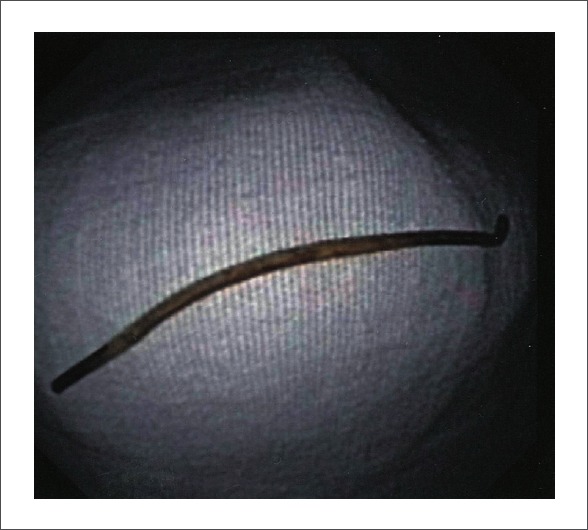

A pediatric colonoscope was used during the ERCP to reach the pancreaticoduodenostomy and the choledochoduodenostomy sites. The migrated pancreatic stent was seen protruding out of the CBD into the duodenal lumen through the choledochoduodenostomy orifice (Fig. 1 and 2). The stent was successfully retrieved with a snare (Fig. 3). Multiple stone fragments and a large amount of sludge were removed from the biliary tree using an extraction balloon. The patient was discharged after the procedure with complete resolution of her symptoms.

Figure 1.

Migrated Stent in the Choledocho-duodenostomy orifice

Figure 2.

Thick Arrow: Pneumobilia; Thin Arrow: Migrated pancreatic stent.

Figure 3.

Migrated pancreatic stent after removal

Discussion

Pancreatic duct stent placement during Whipple procedure is a common practice for bridging the pancreatico-enteric anastomosis1 to prevent failure of anastomosis site and leakage of proteolytic enzymes from pancreas. Leakage of pancreatic enzymes could cause autolysis of normal tissue leading to inadequate healing of the anastomosis and surgical wound.2 The incidence of pancreatic fistula is as high as 24% and it can lead to bleeding, abscess, sepsis and death.3–6 Published studies have reported inconsistent outcomes with regards to the effectiveness of internal versus external pancreatic stenting in a patient with pancreaticojejunal anastomosis. There was no substantial variation in morbidity, mortality and hospital stay between the external and the internal pancreatic duct stent groups.7,8

Most of the pancreatic duct stents will ultimately migrate into the small bowel and clear from the intestine spontaneously. However, these stents could be retained at the pancreatico-enteric anastomosis site, migrate inward into the pancreatic duct, or migrate outward into the biliary tree through the choledocho-duodenostomy as presented in this case. Early complications from the pancreatic ductal stent placement include pancreatitis, ductal rupture and bleeding.9,10 Late complications include infection, bleeding, pancreatitis, stent occlusion, erosions, ductal perforation, stent fracture, intestinal obstruction, stent migration into the biliary tree and liver abscess.2,11 Inward and outward stent migration rates have been reported in 5.2% and 7.5 % of patients, respectively.12 The approximate time for the detection of stent migration was about one year.13

ERCP is considered the first line therapeutic modality for retrieving migrated pancreatic stents into the biliary system. While a side-viewing duodenoscope is widely used to perform ERCP, this can be challenging in patients with anatomical changes caused by surgery (e.g. Whipple procedure). A pediatric colonoscope or enteroscope might be an option for performing an ERCP when use of a duodenoscope is not feasible.14 Deep enteroscopy techniques including double-balloon enteroscopy represent a significant advancement for performing ERCP in patients with surgically altered anatomy.15 However, they are not yet widely performed and often incompatible with ERCP accessories. Other invasive therapeutic options such as surgery or percutaneous approaches are used for removal of a migrated pancreatic stent in patients who fail ERCP.16

Conclusion

In post Whipple procedure, pancreatic stent migration into the biliary tree through the choledochoduodenostomy site is a potential cause of recurrent biliary colic. ERCP is a safe and effective modality for removing these stents and clearing the biliary tree of any associated stone and debris.

Abbreviations

- CBD

common bile duct

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/jig

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Biehl T, Traverso LW. Is stenting necessary for a successful pancreatic anastomosis? Am J Surg. 1992;163:530–532. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(92)90403-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rezvani M, O'Moore PV, Pezzi CM. Late pancreaticojejunostomy stent migration and hepatic abscess after Whipple procedure. J Surg Educ. 2007;64:220–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roder JD, Stein HJ, Bottcher KA, Busch R, Heidecke CD, Siewert JR. Stented versus nonstented pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreatoduodenectomy: a prospective study. Ann Surg. 1999;229:41–48. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199901000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imaizumi T, Harada N, Hatori T, Fukuda A, Takasaki K. Stenting is unnecessary in duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy even in the normal pancreas. Pancreatology. 2002;2:116–121. doi: 10.1159/000055901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winter JM, Cameron JL, Campbell KA, et al. Does pancreatic duct stenting decrease the rate of pancreatic fistula following pancreaticoduodenectomy? Results of a prospective randomized trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:1280–1290. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2006.07.020. discussion 90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tani M, Onishi H, Kinoshita H, et al. The evaluation of duct-to-mucosal pancreaticojejunostomy in pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Surg. 2005;29:76–79. doi: 10.1007/s00268-004-7507-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohwada S, Tanahashi Y, Ogawa T, et al. In situ vs ex situ pancreatic duct stents of duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy with billroth I-type reconstruction. Arch Surg. 2002;137:1289–1293. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.11.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, et al. External drainage of pancreatic duct with a stent to reduce leakage rate of pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:425–433. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181492c28. discussion 33–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smits ME, Badiga SM, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Long-term results of pancreatic stents in chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;42:461–467. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(95)70051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cremer M, Deviere J, Delhaye M, Balze M, Vandermeeren A. Stenting in severe chronic pancreatitis: results of medium-term follow-up in seventy-six patients. Bildgebung. 1992;59:20–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biffl WL, Moore EE. Pancreaticojejunal stent migration resulting in “bezoar ileus”. Am J Surg. 2000;180:115–116. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00422-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johanson JF, Schmalz MJ, Geenen JE. Incidence and risk factors for biliary and pancreatic stent migration. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:341–346. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(92)70429-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price LH, Brandabur JJ, Kozarek RA, Gluck M, Traverso WL, Irani S. Good stents gone bad: endoscopic treatment of proximally migrated pancreatic duct stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:174–179. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elton E, Hanson BL, Qaseem T, Howell DA. Diagnostic and therapeutic ERCP using an enteroscope and a pediatric colonoscope in long-limb surgical bypass patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:62–67. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70300-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Layec S, D'Halluin PN, Pagenault M, Sulpice L, Meunier B, Bretagne JF. Removal of transanastomotic pancreatic stent tubes after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a new role for double-balloon enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:449–451. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.03.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lahoti S, Catalano MF, Geenen JE, Schmalz MJ. Endoscopic retrieval of proximally migrated biliary and pancreatic stents: experience of a large referral center. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:486–491. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70249-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]