Introduction

The human body has adapted to daily changes in dark and light such that it anticipates periods of sleep and activity. Deviations from this circadian rhythm come with functional consequences. Thus, 17 hours of sustained wakefulness in adults leads to a decrease in performance equivalent to a blood alcohol-level of 0.05%;[1] the legal level for drink driving in many countries.[2] Rats deprived of sleep die after 32 days,[3] and, with longer periods of sleep deprivation, this would also be the case in human beings. Indeed, sleep deprivation is a common form of torture.[4]

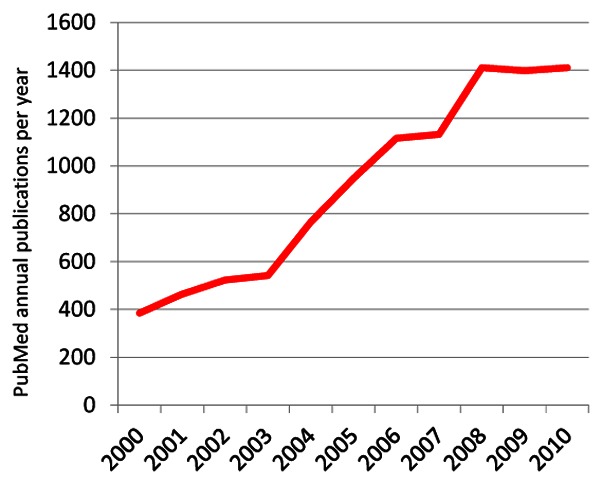

Given the readily observable effects of sleep in everyday life, it is not surprising that there has been scholarly interest in sleep since the beginning of recorded history.[5] Sleep epidemiology as a subject in its own right has a recognisable history of just over 30 years,[6] with the first modern epidemiological studies of sleep disturbances appearing around 1980.[7;8] Nevertheless, a PubMed search for terms “sleep/insomnia” and “epidemiology” shows that the cumulative number of papers on the subject over the past 10 years is already about 10,000. Although this is less than for standard risk factors, such as obesity (>60,000) and smoking (50,000)(Figure 1), the annual number of papers on sleep epidemiology is rising rapidly (Figure 2). This issue of IJE includes a review[9] of the first comprehensive textbook of Sleep Epidemiology,[10] and the purpose of our Editorial is further to highlight recent developments to give the reader an idea why the coming years are likely to see an increasing interest in sleep studies.

Figure 1.

Exposures AND Epidemiology 2000–2010

Figure 2.

Sleep/insomnia AND Epidemiology by year

Why the upsurge in interest?

There are several reasons for an increase in interest in sleep from an epidemiological perspective. First, sleep problems are associated with accidents and human errors. It has been estimated that 10–15% of fatal motor-vehicle crashes are due to sleepiness or driver fatigue. Furthermore, by 2020 the number of people killed in motor-vehicle crashes is expected to double to 2.3 million deaths worldwide, of which approximately 230,000–345,000 will be due to sleepiness or fatigue.[11] It has been estimated that nearly 100,000 deaths occur each year in US hospitals due to medical errors and sleep deprivation have been shown to make a significant contribution.[12] Similarly, in a national sample in Sweden of over 50,000 people interviewed over 20 years disturbed sleep almost doubled the risk of a fatal accident at work.[13]

Second, sleep problems are common. Population studies show that sleep deprivation and disorders affect many more people worldwide than had been previously thought. A recent study found 20% of 25–45 year-olds slept “90 minutes less than they needed to be in good shape”.[14] Insomnia is the most common specific sleep disorder, with ‘some insomnia problems over the past year’ reported by approximately 30% of adults and chronic insomnia by approximately 10%.[15] Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnoea, characterized by respiratory difficulties during sleep, is also very high with estimates of 9–21% in women and 24–31% in men.[16;17]

Third, sleep problems are likely to increase. The rapid advent of the 24/7 society involving round-the-clock activities and increasing night time use of TV, internet and mobile phones mean that adequate sleep durations may become increasingly compromised. Some data suggest a decline in sleep duration of up to 18 minutes per night over the past 30 years.[18;19] Complaints of sleeping problems have increased substantially over the same period, with short sleep (<6 hours/night) in full-time workers becoming more prevalent.[19;20] As more shift work is required to service 24/7 societies the proportion of workers exposed to circadian rhythm disorders, such as shift work sleep disorder, and their effects on health and performance is likely to rise. Sleep architecture is known to change with age; slow-wave (or deep) sleep decreases and lighter sleep increases. Other changes include increases in nocturnal sleep disruption and daytime sleepiness. As the proportion of elderly people in populations across the world increases, these changing sleep patterns will raise the prevalence of sleep disorders. Similarly, the increasing worldwide obesity epidemic and the prevalence of obstructive sleep apnoea, which is over double among the obese, ensure sleep disorders will be of increasing public health importance in lower as well as high income countries.[16;21]

Fourth, sleep problems are associated with short and long-term effects on health and well-being. Immediate effects at the individual level relate to well-being, performance, daytime sleepiness and fatigue. Longer term, evidence has accumulated of associations between sleep deprivation and sleep disorders and numerous health outcomes including premature mortality, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, inflammation, obesity, diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance, and psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and depression. As this evidence represents the core of Sleep Epidemiology, we provide below a snapshot on key findings.

Sleep as a risk factor for mortality and chronic conditions

Two recent meta-analyses confirm associations between premature all-cause mortality and both shorter (less than 7 hours) and longer sleep (more than 8 hours),[22;23] although not all studies show this association to be U-shaped.[24] Another meta-analysis also suggests that both short and long sleep are associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease and stroke.[25] Potential explanations of these associations are provided by evidence of the impact of sleep on an array of disease risk factors, in particular cardiovascular disease. First, short and long sleep are associated with an increased prevalence of hypertension,[26] with some evidence of sex-specific effects.[27;28] Insomnia and obstructive sleep apnoea have also been linked to higher rates of hypertension. However, intervention studies of continuous positive airway pressure, the recommended treatment for obstructive sleep apnoea, have produced only modest antihypertensive effects.[29]

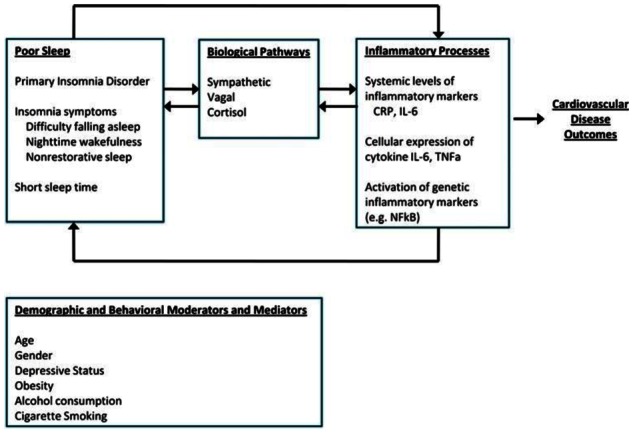

Second, experimental studies in animal and humans provide evidence that sleep loss affects inflammatory markers. Although the findings are complex, there is compelling evidence that in humans sleep restriction is associated with increases in inflammatory markers with some evidence of bidirectional effects – Figure 3,[30;31] and that inflammatory responses are increased in people with obstructive sleep apnoea.[32] Results from observational studies also show that treatment of sleep disorders reduces levels of inflammatory markers, but evidence from randomised controlled trials remains equivocal.[33]

Figure 3.

Sleep, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease outcomes (from reference[30] with permission)

Third, major sleep disorders are more prevalent among the obese, a meta-analysis has suggested an association between short sleep and obesity,[34] although results from prospective studies do not provide consistent evidence that short sleep predicts the future development of obesity.[35;36] In the general population one extra hour of sleep is associated with a lower body mass index (0.35 units).[34] While unimportant at the individual level this is will have greater significance at the population level.[37] For example, based on prevalence data from published studies it has been calculated that 3–5% of the overall proportion of obesity in adults could be attributable to short sleep.[38]

Fourth, sleep plays an important role in the release of many hormones and has the potential to disrupt endocrine function. Many cross-sectional studies have observed significant associations between short sleep and diabetes. A meta-analysis of prospective studies that included 3,586 incident cases of type 2 diabetes confirmed the risk of incident diabetes associated with short sleep and suggested some associations also with long sleep and insomnia symptoms – Figure 4.[39] Laboratory studies, which have shown sleep restriction and poor quality sleep to be linked to glucose dysregulation and increases in hunger and appetite via down-regulation of the satiety hormone, leptin, and up-regulation of the appetite-stimulating hormone, ghrelin,[40] indicate pathways to diabetes via insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome.[41;42]

Figure 4.

Meta-regression of the risk of developing type 2 diabetes by duration of follow-up according to type of sleep disturbance. The size of circles is proportional to the weight of the study. DIS, difficulty in initiating sleep; DMS, difficulty in maintaining sleep. Reference group is those free of the particular sleep problem. (from reference[39] with permission)

Finally, the common mental disorders, in particular depression, are the most prevalent of the conditions associated with problem sleep. With insomnia included in the diagnostic criteria for depression the assumption tended to be that insomnia was a symptom of depression. However, studies over the last 10 years have provided evidence that insomnia could be a separate condition, albeit one that shows high co-morbidity with depression, that insomnia could lead to depression, or common causes, such as a heightened level of arousal, could underlie the two disorders.[43] A review of studies that simultaneously examined the effects of sleep and depression on cardiometabolic disease showed sleep to be associated with cardiometabolic diseases, independent of depression. However, it was unclear if the effects of depression were independent of sleep duration.[44] Less attention has been paid to the association between sleep and anxiety. Findings generally resemble those for depression, again with evidence of a shift from the assumption that the association is unidirectional, from anxiety to insomnia, to an appreciation of bidirectional effects,[45] and evidence of insomnia as a risk factor for the development of anxiety.[46]

Progress in methodology

Sleep epidemiology in the future will be strengthened by recent methodological developments in the assessment of sleep. A limitation common to most studies of sleep duration is reliance on self-report measures, in which response categories are frequently hourly intervals and which, in general, do not ask respondents to differentiate time asleep from time in bed. Obtaining data using polysomnography (a comprehensive recording of the biophysiological changes that occur during sleep) is expensive and time consuming and therefore has not yet been considered feasible in large-scale epidemiologic studies. However, actigraphy, a less expensive objective measure, is now increasingly being introduced on a larger scale.[47] The actigraph, generally worn on the wrist, can measure movements in 3 directions 24 hours a day for up to several days. It appears to be a reliable and valid measure of sleep duration and quality, and measurements one year apart have produced consistent results.[48]

Similar problems pertain to the ascertainment of sleeping problems and disorders in observational epidemiological studies. A number of well validated questionnaires for the ascertainment of insomnia are available and are appropriate for self-completion. However, individuals suffering from sleep-disordered breathing disorders and parasomnias may be unaware of symptoms other than daytime sleepiness, which can be due to a range of factors. Due to the strong association between snoring and apnoea, self-reported or partner-reported snoring is often used as a proxy measure of apnoea in population-bases studies. Unattended home polysomnography using portable digital recorders is an emerging and reliable method of recording sleep.[49;50] Although still relatively expensive compared to actigraphy, home polysomnography is much cheaper, more naturalistic and representative of usual sleep, and less subject to first-night effects than laboratory recording.

Although technological developments in relation to actigraphy and polysomnography continue apace, it will undoubtedly be some years before repeat recorded data on large numbers of individuals are available. At present there are probably more data available for the simple self-reported question ‘how many hours do you sleep on an average night?’ than for any other measure of sleep and much useful work can be achieved using large cohort studies in which there are repeat data for this measure. Assessments of sleep duration and preliminary diagnoses of sleep disorders in the primary healthcare setting also rely on self-reported data from patients and it is important to highlight the finding that self-reported sleep duration and disorders are strongly associated with health outcomes.

New and developing areas of interest

What will be the next steps in sleep epidemiology? There several new lines of research are emerging. One is increasing recognition that it is not only sleep duration and presence of sleep disturbances but also change in these parameters over time that is of relevance to future health. In a cohort of over 25,000 Finnish employees, for example, repeated measurements of sleep disturbances, compared to a single measurement, improved prediction of future work disability by over 10%.[51] An increase in sleep disturbances was associated with greater risk of disability due to depressive disorders whereas disabling injuries were best predicted by continuous severe sleep problems. Corresponding findings have been obtained for sleep duration in relation to mortality [52;53] and cognitive function.[54] In the Whitehall II study a reduction in sleep duration among participants who regularly slept 6, 7 or 8 hours at baseline was associated with an increased risk of mortality, mainly due to cardiovascular deaths. An increase in usual sleep duration from 7 or 8 hours at baseline, in turn, was associated with an increased risk of mortality, mainly due to non-cardiovascular deaths.[52] A further study using Whitehall II data examined how change in sleep duration occurring over a five-year period in late middle age was associated with cognitive function in later life. The findings suggest that women and men who begin sleeping more or less than 6 to 8 hours per night are subject to an accelerated cognitive decline that is equivalent to four to seven years of ageing.[54]

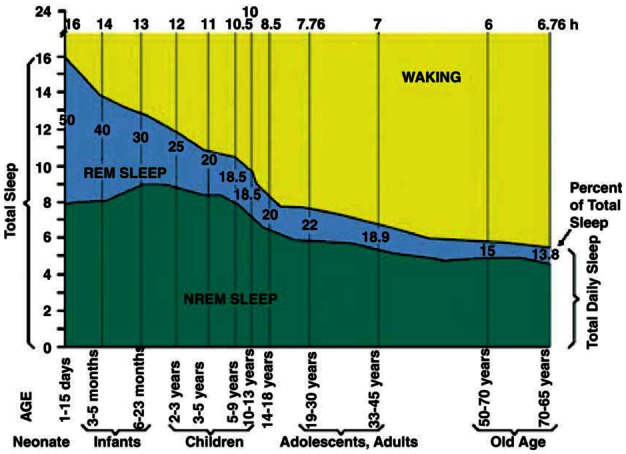

Authors of a recent review that detected similarities between age-related and insomnia-related cognitive and brain changes suggested that at least part of what is regarded as age-related change may, in fact, be due to poor sleep.[55] However, given the strong association between age and sleep over the lifecourse (Figure 5) distinct effects for sleep and ageing may be difficult to disentangle in observation studies. The age-related changes in sleep architecture are well known. In addition, the prevalence of many primary sleep disorders and daytime sleepiness increases with age.[56;57] These factors, combined with an increasing proportion of elderly in most populations worldwide mean that the role of sleep as a potential risk factor for adverse ageing outcomes is likely to attract increasing attention. For example, in laboratory settings sleep deprivation has been shown to have adverse consequences for contiguously measured cognitive performance,[58] and poor sleep is a feature of dementia,[59] although we do not yet know whether long-term sleep problems actually increase the risk of dementia.

Figure 5.

Sleep becomes shorter with age (from reference[57] with permission)

Finally, genetics provides a new way to address the regulation, function and consequence of sleep. Recent data from genetic studies support the notion that there are common pathways that underlie circadian rhythm and health outcomes. Overlapping pathways have been particularly noted in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of metabolic markers and disease. Thus risk variants from genes that have traditionally been related to sleep regulation, such as melatonin receptor 1 B (MTNR1B), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and a circadian pacemaker gene cryptochrome 2 (CRY2), have now been found to be associated with markers of glycaemic homeostasis, obesity and type 2 diabetes.[60]–[65] BDNF encodes brain-derived nerve growth factor and has also been thought to underpin associations of sleep, learning and memory.[66] A particularly interesting finding relates to a suggested positive association between phosphodiesterase 4D ( PDE4D) and ‘sleepiness’.[67] A PDE4-specific inhibitor, rolipram, has antidepressant effects in patients with major depression,[68] pointing to common pathways between some aspects of sleep and depression. Thus, genetic data point to a number of pathways linking sleep, circadian rhythm, metabolism, functioning and disease. We anticipate further insights from genetics to sleep epidemiology in the near future as studies are underway that seek to examine genome wide determinants of sleep duration.[69]

References

- 1.Dawson D, Reid K. Fatigue, alcohol and performance impairment. Nature. 1997;388(6639):235. doi: 10.1038/40775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blood Alcohol Concentration Limits Worldwide. Jan 12, 2010. 1-10-2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rechtschaffen A, Bergmann BM, Everson CA, Kushida CA, Gilliland MA. Sleep deprivation in the rat: X. Integration and discussion of the findings 1989. Sleep. 2002;25(1):68–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iacopino V, Xenakis SN. Neglect of medical evidence of torture in Guantanamo Bay: a case series. PLoS Med. 2011;8(4):e1001027. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thorpy MJ. History of sleep and man. In: Pollak CP, Thorpy MJ, Yager J, editors. Encyclopedia of sleep and sleep disorders. 3. New York: Facts on File Incoporated; 2009. pp. xvii–xxxix. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ohayon MM, Guilleminault C, Chokroverty S. Sleep epidemiology 30 years later: where are we? Sleep Med. 2010;11(10):961–962. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bixler EO, Kales A, Soldatos CR, Kales JD, Healey S. Prevalence of sleep disorders in the Los Angeles metropolitan area. Am J Psychiatry. 1979;136(10):1257–1262. doi: 10.1176/ajp.136.10.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavie P. Sleep habits and sleep disturbances in industrial workers in Israel: main findings and some characteristics of workers complaining of excessive daytime sleepiness. Sleep. 1981;4(2):147–158. doi: 10.1093/sleep/4.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kronholm E. Two faces of sleep and epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2011;40(6):x–xi. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sleep, Health, and Society. From Aetiology to Public Health. Oxford: OUP; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pandi-Perumal SR, Verster JC, Kayumov L, Lowe AD, Santana MG, Pires ML, et al. Sleep disorders, sleepiness and traffic safety: a public health menace. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2006;39:863–871. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2006000700003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Committee on Sleep Medicine and Research Board on Health Sciences Policy. Sleep Disorders and Sleep Deprivation: An Unmet Public Health Problem. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akerstedt T, Fredlund P, Gillberg M, Jansson B. A prospective study of fatal occupational accidents -- relationship to sleeping difficulties and occupational factors. J Sleep Res. 2002;11(1):69–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2002.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leger D, Roscoat E, Bayon V, Guignard R, Paquereau J, Beck F. Short sleep in young adults: Insomnia or sleep debt? Prevalence and clinical description of short sleep in a representative sample of 1004 young adults from France. Sleep Med. 2011;12(5):454–462. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown WD. Insomnia: Prevalence and daytime consequences. In: Lee-Chiong T, editor. Sleep: A Comprehensive Handbook. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley and Sons; 2006. pp. 93–98. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li C, Ford ES, Zhao G, Croft JB, Balluz LS, Mokdad AH. Prevalence of self-reported clinically diagnosed sleep apnea according to obesity status in men and women: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005–2006. Prev Med. 2010;51(1):18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kronholm E, Partonen T, Laatikainen T, Peltonen M, Harma M, Hublin C, et al. Trends in self-reported sleep duration and insomnia-related symptoms in Finland from 1972 to 2005: a comparative review and re-analysis of Finnish population samples. J Sleep Res. 2008;17:54–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00627.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rowshan RA, Bengtsson C, Lissner L, Lapidus L, Bjorkelund C. Thirty-six-year secular trends in sleep duration and sleep satisfaction, and associations with mental stress and socioeconomic factors--results of the Population Study of Women in Gothenburg, Sweden. J Sleep Res. 2010;19(3):496–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knutson KL, Van CE, Rathouz PJ, DeLeire T, Lauderdale DS. Trends in the prevalence of short sleepers in the USA: 1975–2006. Sleep. 2010;33(1):37–45. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma SK. Wake-up call for sleep disorders in developing nations. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:115–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gallicchio L, Kalesan B. Sleep duration and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sleep Res. 2009;18:148–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010;33(5):585–592. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.5.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrie JE, Kivimaki M, Shipley M. Sleep and death. In: Cappuccio FP, Miller MA, Lockley SW, editors. Sleep, Health, and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 50–82. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cappuccio FP, Cooper D, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur Heart J. 2011 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buxton OM, Marcelli E. Short and long sleep are positively associated with obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease among adults in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(5):1027–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cappuccio FP, Stranges S, Kandala NB, Miller MA, Taggart FM, Kumari M, et al. Gender-specific associations of short sleep duration with prevalent and incident hypertension: the Whitehall II Study. Hypertension. 2007;50(4):693–700. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.095471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stranges S, Dorn JM, Cappuccio FP, Donahue RP, Rafalson LB, Hovey KM, et al. A population-based study of reduced sleep duration and hypertension: the strongest association may be in premenopausal women. J Hypertens. 2010;28(5):896–902. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328335d076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Calhoun DA, Harding SM. Sleep and hypertension. Chest. 2010;138(2):434–443. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-2954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Motivala SJ. Sleep and inflammation: psychoneuroimmunology in the context of cardiovascular disease. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42(2):141–152. doi: 10.1007/s12160-011-9280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mullington JM, Simpson NS, Meier-Ewert HK, Haack M. Sleep loss and inflammation. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;24(5):775–784. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gozal D, Kheirandish-Gozal L. Cardiovascular morbidity in obstructive sleep apnea: oxidative stress, inflammation, and much more. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(4):369–375. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1190PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller MA, Cappuccio FP. Sleep, inflammation, and disease. In: Cappuccio FP, Miller MA, Lockley SW, editors. Sleep, Health, and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2010. pp. 239–268. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cappuccio FP, Taggart FM, Kandala NB, Currie A, Peile E, Stranges S, et al. Meta-analysis of short sleep duration and obesity in children and adults. Sleep. 2008;31(5):619–626. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.5.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stranges S, Cappuccio FP, Kandala NB, Miller MA, Taggart FM, Kumari M, et al. Cross-sectional versus prospective associations of sleep duration with changes in relative weight and body fat distribution: the Whitehall II Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:321–329. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Rathouz PJ, Yan LL, Hulley SB, Liu K. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between objectively measured sleep duration and body mass index: the CARDIA Sleep Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(7):805–813. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol. 1985;14:32–38. doi: 10.1093/ije/14.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Young T. Increasing sleep duration for a healthier (and less obese? ) population tomorrow Sleep. 2008;31(5):593–594. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.5.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Quantity and quality of sleep and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):414–420. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Spiegel K, Tasali E, Leproult R, Van CE. Effects of poor and short sleep on glucose metabolism and obesity risk. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5(5):253–261. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Cauter E. Sleep disturbances and insulin resistance. Diabetic Med. 2011 Sep 26; doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03459.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lam JC, Ip MS. Sleep & the metabolic syndrome. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:206–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Staner L. Comorbidity of insomnia and depression. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(1):35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mezick EJ, Hall M, Matthews KA. Are sleep and depression independent or overlapping risk factors for cardiometabolic disease? Sleep Med Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jansson-Frojmark M, Lindblom K. A bidirectional relationship between anxiety and depression, and insomnia? A prospective study in the general population. J Psychosom Res. 2008;64(4):443–449. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Neckelmann D, Mykletun A, Dahl AA. Chronic insomnia as a risk factor for developing anxiety and depression. Sleep. 2007;30:873–880. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.7.873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van den Berg JF, Van Rooij FJ, Vos H, Tulen JH, Hofman A, Miedema HM, et al. Disagreement between subjective and actigraphic measures of sleep duration in a population-based study of elderly persons. J Sleep Res. 2008;17:295–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knutson KL, Rathouz PJ, Yan LL, Liu K, Lauderdale DS. Intra-individual daily and yearly variability in actigraphically recorded sleep measures: the CARDIA study. Sleep. 2007;30(6):793–796. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.6.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Portier F, Portmann A, Czernichow P, Vascaut L, Devin E, Benhamou D, et al. Evaluation of home versus laboratory polysomnography in the diagnosis of sleep apnea syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(3 Pt 1):814–818. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.9908002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Unruh ML, Redline S, An MW, Buysse DJ, Nieto FJ, Yeh JL, et al. Subjective and objective sleep quality and aging in the sleep heart health study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1218–1227. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Salo P, Hall M, Rod NH, Virtanen M, Pentti J, Sjosten N, et al. Using repeated measures of sleep disturbances to predict future diagnisis-specific work diability: A cohort syudy. Sleep. 2011 doi: 10.5665/sleep.1746. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Cappuccio FP, Brunner E, Miller MA, Kumari M, et al. A prospective study of change in sleep duration: associations with mortality in the Whitehall II cohort. Sleep. 2007;30:1659–1666. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.12.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hublin C, Partinen M, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J. Sleep and mortality: a population-based 22-year follow-up study. Sleep. 2007;30:1245–1253. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.10.1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Akbaraly TN, Marmot MG, Kivimaki M, Singh-Manoux A. Change in sleep duration and cognitive function: findings from the Whitehall II Study. Sleep. 2011;34(5):565–573. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Altena E, Ramautar JR, Van Der Werf YD, Van Someren EJ. Do sleep complaints contribute to age-related cognitive decline? Prog Brain Res. 2010;185:181–205. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53702-7.00011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Roepke SK, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep disorders in the elderly. Indian J Med Res. 2010;131:302–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pandi-Perumal SR, Seils LK, Kayumov L, Ralph MR, Lowe A, Moller H, et al. Senescence, sleep, and circadian rhythms. Ageing Res Rev. 2002;1(3):559–604. doi: 10.1016/s1568-1637(02)00014-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Durmer JS, Dinges DF. Neurocognitive consequences of sleep deprivation. Semin Neurol. 2005;25(1):117–129. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-867080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bliwise DL. Sleep in normal aging and dementia. Sleep. 1993;16(1):40–81. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bouatia-Naji N, Bonnefond A, Cavalcanti-Proenca C, Sparso T, Holmkvist J, Marchand M, et al. A variant near MTNR1B is associated with increased fasting plasma glucose levels and type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet. 2009;41(1):89–94. doi: 10.1038/ng.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prokopenko I, Langenberg C, Florez JC, Saxena R, Soranzo N, Thorleifsson G, et al. Variants in MTNR1B influence fasting glucose levels. Nat Genet. 2009;41(1):77–81. doi: 10.1038/ng.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Soranzo N, Sanna S, Wheeler E, Gieger C, Radke D, Dupuis J, et al. Common variants at 10 genomic loci influence hemoglobin A(C) levels via glycemic and nonglycemic pathways. Diabetes. 2010;59(12):3229–3239. doi: 10.2337/db10-0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Thorleifsson G, Walters GB, Gudbjartsson DF, Steinthorsdottir V, Sulem P, Helgadottir A, et al. Genome-wide association yields new sequence variants at seven loci that associate with measures of obesity. Nat Genet. 2009;41(1):18–24. doi: 10.1038/ng.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Speliotes EK, Willer CJ, Berndt SI, Monda KL, Thorleifsson G, Jackson AU, et al. Association analyses of 249,796 individuals reveal 18 new loci associated with body mass index. Nat Genet. 2010;42(11):937–948. doi: 10.1038/ng.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dupuis J, Langenberg C, Prokopenko I, Saxena R, Soranzo N, Jackson AU, et al. New genetic loci implicated in fasting glucose homeostasis and their impact on type 2 diabetes risk. Nat Genet. 2010;42(2):105–116. doi: 10.1038/ng.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Monteggia LM, Barrot M, Powell CM, Berton O, Galanis V, Gemelli T, et al. Essential role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in adult hippocampal function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(29):10827–10832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402141101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gottlieb DJ, O’Connor GT, Wilk JB. Genome-wide association of sleep and circadian phenotypes. BMC Med Genet. 2007;8 (Suppl 1):S9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-8-S1-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Scott AI, Perini AF, Shering PA, Whalley LJ. In-patient major depression: is rolipram as effective as amitriptyline? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1991;40(2):127–129. doi: 10.1007/BF00280065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sleep timing/duration, seasonality and metabolic phenotypes. 41st Annual Conference; International Society Psychoneuroendocrinology; 2011. [Google Scholar]