Abstract

Background

Gastroduodenal outlet obstruction (GOO) is a critical complication of cancers localized within and adjacent to the upper gastrointestinal tract. Approaches to the relief of GOO include surgical bypass with gastrojejunostomy (GJ), endoluminal placement of a self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS), and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy with jejunal extension (PEG-J). To date no studies have compared the outcome of utilizing PEG-J with other modalities of therapy.

Objectives

To determine if there is a difference in complications or effectiveness when survival and/or device patency of PEG-J is compared to that of gastroduodenal SEMS in patients with malignant GOO.

Methods

Patients who underwent placement of either PEG-J or gastroduodenal SEMS for unresectable malignant GOO were included in a retrospective cohort study.

Results

24 patients (12 men) with a median age of 68.5 years underwent either PEG-J (n=12) or gastroduodenal SEMS (n=12) placement. Patients undergoing SEMS placement experienced longer overall device patency and/or survival as compared to those undergoing PEG-J (median 70 versus 35 days). Complications, including the need for re-intervention, were similar among both groups. Patients who underwent PEG-J as compared to those that had SEMS placement had a hazard ratio of 3.85 (CI 1.28–11.11) for decreased overall survival.

Conclusion

In patients with malignant GOO, placement of a palliative SEMS for gastric decompression and nutrition was associated with longer aggregate device patency and survival as compared to PEG-J. Both modalities were similar with respect to complications and the need for re-intervention.

Key words: percutaneous endoscopic gastrojejunostomy, PEG-J, gastric outlet obstruction, duodenal obstruction, stents

Introduction

Inoperable malignant gastroduodenal outlet obstruction (GOO) is a debilitating complication of advanced tumors that arise from the antrum, duodenum or pancreaticobiliary axis. Most frequently, malignant GOO arises in patients with pancreatic adenocarcinomas but may also be seen in patients with distal gastric carcinoma, duodenal and ampullary carcinoma, lymphoma, cholangiocarcinoma or metastatic disease of remote origin.1–4 In these patients, obstruction typically results in rapid and significant morbidity in the form of intractable nausea, vomiting, malnutrition, volume depletion, and severe electrolyte abnormalities.5

Optimal palliative treatment for malignant GOO includes gastric decompression and enteral access to the more distal small bowel for nutrition. This can be accomplished surgically by gastrojejunostomy (GJ) which bypasses the affected gastroduodenal segment. Endoscopic options include percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) with placement of an indwelling jejunal feeding tube (PEG-J) or placement of an uncovered self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS). Historically, surgical bypass was considered to be the preferred treatment modality because of its high-rate of success, relief of symptoms, ability to restore oral intake. However, this approach is limited by substantial perioperative morbidity (13–55%) in patients who are often poor candidates for surgical intervention.3.6–9 A randomized control trial that compared gastroduodenal SEMS placement with surgical bypass concluded that stent placement was favored in patients with a shortened anticipated survival time (< 2 months) on the basis of earlier resumption of oral intake (median of 5 days for SEMS versus 8 days for GJ) and shorter length of hospitalization. The authors argued that patients with longer expected survival were felt to benefit from surgical bypass due to the durability of surgical intervention (median of 70 days for surgical GJ versus 52 days for SEMS) and fewer major complications (such as, recurrent obstructive symptoms and need for reintervention).10 A systematic review of 44 individual studies containing 1,343 patients that compared surgery to stent placement concluded that these modalities were comparable for treatment of malignant GOO.

PEG-J was first described by Wadiwala11 in 1986 and is an alternative treatment for GOO. Little data exists regarding the use of PEG-J in the palliation of malignant GOO. Schmidt et al12 studied patients who underwent PEG or percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy (PEJ), surgical bypass, or endoscopic stent placement for malignant GOO, but none of the patients in this series underwent PEG-J. This study included only seven patients in the PEG/PEJ arm, four of whom had failed attempts at stent placement. Patients in the PEG/PEJ arm experienced the worst overall survival in terms of 30-day mortality (29%) in comparison to both the stent (4%) and the surgical (25%) groups.12 Overall, data on use of PEG-J for palliation of GOO are lacking. The aim of this study was to determine if there is a difference in complications or effectiveness when survival and/or device patency of PEG-J is compared to that of gastroduodenal stent placement in patients with malignant GOO.

Methods

Patients who underwent PEG-J or gastroduodenal SEMS placement for malignant GOO between August 2007 and January 2011, at the University of Virginia Health System, were identified and their electronic medical records were reviewed. Patients who had incurable malignancy (any source) resulting in symptomatic obstruction of the distal stomach and/or duodenum were included. Patients who had surgically altered gastroduodenal anatomy before developing cancer were excluded. Baseline ECOG/WHO scores were obtained from medical oncology notes or estimated based on physical and occupational therapy assessments. The social security death index (SSDI) was queried to assist in obtaining mortality data. This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board.

Endoscopic procedures

Patients in the PEG-J group underwent PEG placement via either the standard push or pull technique, adapted from the method as first described by Ponsky and Gauderer,13 and received a 24-Fr diameter gastrostomy tube (Wilson-Cook, Winston-Salem, NC). Subsequently, an indwelling 12 Fr x 60 or 90 cm jejunal feeding tube (Wilson-Cook) was fluoroscopically guided through the gastrostomy tube, across the gastroduodenal stricture, and left distal to the ligament of Trietz. Patients in the endoluminal stent group underwent placement of an uncovered gastroduodenal SEMS (Wallstent or Wallflex, Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass) with a diameter of 22 mm and a length of 60, 90, or 120 mm. Gastroduodenal SEMS were deployed using a therapeutic gastroscope or duodenoscope (GIF-1TQ160, GIF-2T160, TJF-160VF; Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) and a long hydrophilic guidewire that was deployed across the strictured segment using fluoroscopic guidance. All procedures were performed by one of three endoscopists who routinely perform more than 500 interventional endoscopies each year.

Diagnosis of GOO and definitions

The diagnosis of GOO was made via a combination of clinical, radiological, and endoscopic data. All patients included in the study could not maintain adequate nutrition or hydration via oral intake, and a standardized GOO Scoring System (GOOSS) score was assigned to each patient (0 = no oral intake, 1 = liquid intake only).10

Complications were divided into early vs. late and major vs. minor. Early complications occurred ≤7 days of the procedural intervention, and late complications occurred >7 days. Major complications were defined as per Jeurnik et al14 and included perforation, stent migration, hemorrhage, fever, jaundice, and severe pain necessitating hospitalization. Recurrent or persistent symptomatic obstruction was also considered a major complication. Persistent obstructive symptoms were defined as those that continued post-procedure or recurred within 7 days, while recurrent obstructive symptoms were defined as those returning after 7 days that were related to device failure/occlusion. Minor complications were defined as non-life threatening and did not require hospital admission (eg, non-severe pain, wound infection, or recurrent vomiting without evidence of obstruction). A re-intervention was defined as a procedure performed for management of a complication or on the basis of either persistent or recurrent symptoms. Overall survival was defined as the length of time between the initial procedure and patient death, recurrent or persistent obstruction, or last-follow up.

Statistical analysis

Categorical and continuous baseline data, including demographics and clinical characteristics were compared for homogeneity between patients undergoing PEG-J and gastroduodenal stent placement with Fisher's exact test, Pearson's exact test, or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. A Kaplan-Meier analysis and a Cox-Proportional Hazards Model were used to compare the overall survival between the two study groups. The overall survival hazard ratio for PEG-J:SEMS placement was corrected for age and ECOG score utilizing the Cox model, Type III Wald chi-squared tests, and the Grambsch & Therneau test of the proportional hazards assumption. All reported P-values were two-sided, and a p-value of ≤0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) and Splus version 7.0 (TIBCO, Palo Alto, CA).

Results

Patient characteristics

24 patients (12 men) were identified during the study period with malignant GOO who underwent PEG-J or SEMS placement. 12 patients underwent PEG-J and 12 patients underwent SEMS placement. The median age was 67.0 years (range: 40–88 years) for those who underwent SEMS placement and 72.5 years (range: 51–91 years) for those who underwent PEG-J placement. GOO was caused by pancreatic (67%), duodenal (25%), and gastric (8%) adenocarcinomas in the SEMS group, and by pancreatic (50%), duodenal (8%), and gastric (17%) adenocarcinomas in the PEG-J group. Additionally, the PEG-J group included 3 patients with focal obstruction due to distant metastatic disease (25%; advanced urothelial cancer, n=2; non-small cell lung cancer, n=1). A comparison of patient demographic data and baseline characteristics are listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population according to procedure

| Demographic | SEMS | PEG-J | p-Value | |

| Age, year (mean ± SD) | 63.8 ± 17.1 | 72.2 ± 13.7 | p=0.193 | |

| Sex (male), % | 6 (50.0%) | 6 (50.0%) | p=1.00 | |

| Race (Caucasian), % | 11 (91.7%) | 10 (83.3%) | p=1.00 | |

| Primary Tumor Location | ||||

| Stomach, % | 1 (8.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | p=1.00 | |

| D1–D2, % | 3 (25.0%) | 1 (8.3%) | p=0.59 | |

| Pancreas, % | 8 (66.7%) | 6 (50.0%) | p=0.68 | |

| Obstructive Symptoms at Presentation | ||||

| Nausea / Vomiting, % | 12 (100%) | 12 (100%) | p=1.00 | |

| Abdominal Pain, % | 9 (75.0%) | 7 (58.3%) | p=0.67 | |

| Anorexia, % | 9 (75.0%) | 7 (58.3%) | p=0.67 | |

| Dysphagia, % | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | p=1.00 | |

| Jaundice, % | 3 (25.0%) | 1 (8.3%) | p=0.59 | |

| Weight Loss, % | 12 (100.0%) | 12 (100.0%) | p=1.00 | |

| Medical Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension, % | 9 (75.0%) | 9 (75.0%) | p=1.00 | |

| Hyperlipidemia, % | 4 (33.3%) | 8 (66.7%) | p=0.22 | |

| COPD, % | 4 (33.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | p=0.64 | |

| CAD, % | 3 (25.0%) | 2 (16.7%) | p=1.00 | |

| Heart Failure, % | 1 (8.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | p=1.00 | |

| DVT, % | 1 (8.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | p=1.00 | |

| Diabetes Mellitus, % | 1 (8.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | p=1.00 | |

| Disease Stage at Diagnosis (Staging and TNM by primary tumor type) | ||||

| T-Staging | ||||

| T2, % | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (8.3%) | ||

| T3, % | 8 (66.7%) | 6 (50.0%) | ||

| T4, % | 4 (33.3%) | 5 (41.7%) | ||

| N-Staging | ||||

| N0, % | 5 (41%) | 1 (16.7%) | ||

| N Positive, % | 7 (58.3%) | 5 (83.4%) | ||

| Metastases | 7 (58.3%) | 10 (83.3%) | P=0.307 | |

| Preceding Therapy for Cancer | ||||

| Radiotherapy, % | 8 (66.7%) | 5 (41.7%) | P=0.413 | |

| Chemotherapy, % | 8 (66.7%) | 7 (58.3%) | P=1.00 | |

| ECOG Score | ||||

| 0 | 3 (25.0%) | 1 (8.3%) | p=0.283(Pearson's Exact Test) | |

| 1 | 4 (33.3%) | 3 (25.0%) | ||

| 2 | 2 (16.7%) | 4 (33.3%) | ||

| 3 | 1 (8.3%) | 5 (41.7%) | ||

| 4 | 1 (8.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

Complications and reinterventions

Table 2 demonstrates the early and late complications and the reinterventions that occurred in both groups. No early complications were identified in patients following SEMS placement, while only one early complication occurred following PEG-J. This patient experienced new-onset upper abdominal pain attributed to the PEG's external bolster and did not require hospitalization.

Table 2.

Number of Post-procedural Complications

| Complication Type | SEMS | PEG-J | p | |

| Early | 0 | 1 | p=1.00 | |

| Major | 0 | 0 | ||

| Minor | 0 | 1 | ||

| Late | 3 | 3 | p=1.00 | |

| Major | 2 | 1 | ||

| Minor | 1 | 2 | ||

| Re-intervention | 2 | 1 | p = 1.00 |

Three patients experienced late complications in each of the two treatment groups. In the SEMS group, two major complications and one minor complication occurred. Both major complications were from recurrent gastroduodenal obstruction. One patient had recurrent symptoms 361 days after SEMS placement due to tumor in-growth, which was effectively managed by deployment of a second uncovered SEMS across the strictured segment. The other patient developed recurrent obstructive symptoms within 25 days and was referred for surgical gastrojejunostomy. The minor complication following SEMS placement was mild abdominal pain that responded to analgesics and did not require hospitalization. Following PEG-J, one patient had a late, major complication at 17 days, due to symptoms of recurrent obstruction, which resolved after subsequent SEMS placement. Two patients had late, minor complications including mild abdominal pain (n=1) and vomiting without recurrent obstruction (n=1). There were no statistically significant differences in early or late complications or in the need for re-interventions between the two treatment groups.

Overall survival and device patency

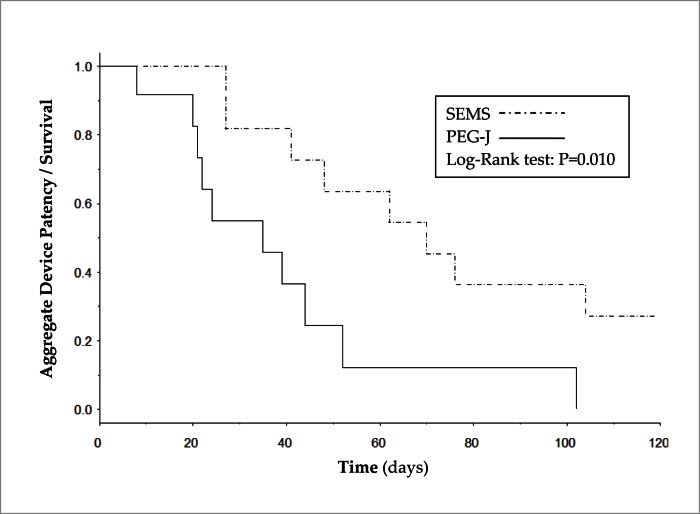

Figure 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier analysis of patients from the time of first intervention until censoring by the primary endpoint defined as mortality, loss of device patency, or last follow-up. Patients who underwent SEMS placement had a median duration of device patency or survival of 70 days while patients who underwent PEG-J had a median duration of device patency or survival of 35 days, and the difference in the two curves was statistically significant (p=0.01). Multivariate hazard analysis adjusted for age and ECOG/WHO performance status found that patients who underwent PEG-J were 3.9 times more likely to experience PEG-J failure or death as compared to those who underwent SEMS placement. Table 3 shows the hazard ratio analyses.

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis comparing aggregate device patency and survival for gastroduodenal SEMS and PEG-J placement.

Table 3.

Hazard Ratio Summary for Cox-Proportional Model

| Ratio | Hazard Ratio | Lower 95% CI | Upper 95% CI |

| PEG-J : SEMS* | 3.85 | 1.28 | 11.11 |

| Age (80 years : 52 years) | 2.67 | 0.92 | 7.72 |

| ECOG 3 : 1 | 11.80 | 2.89 | 48.25 |

Multivariate hazard analysis adjusted for age and ECOG/WHO performance status.

Discussion

Previous work has suggested that surgical GJ may be the most reasonable palliative intervention for malignant GOO in patients with longer anticipated survival.10,14 However, many patients with malignant GOO are poor surgical candidates by the time they are diagnosed.15 Gastroduodenal SEMS placement is the palliative modality that has been most extensively studied as an alternative to surgery. To our knowledge, this present study represents the only available direct comparison of device efficacy and/or survival between endoscopically-placed PEG-J and gastroduodenal SEMS for palliation of inoperable GOO.

Gastroduodenal SEMS have been associated with high technical success rate, low risk of severe peri-procedural complications (less than 1%), and rapid relief of obstructive symptoms,10,15–17 all without the need for surgery or a percutaneous tube. Perhaps most significantly, SEMS placement offers patients the potential to eat, which appears to result in an improved quality of life comparable to that of surgical GJ.12

Decompression of the gastric lumen by PEG-J is accomplished by continuous or intermittent drainage of an external gastrostomy port, which may be easily controlled by the patient. Nutrition and hydration are provided distal to the obstruction by a jejunal feeding tube guided through the PEG. Excess volume and electrolyte loss incurred by gastric drainage may be mitigated through re-infusion of the drained gastric fluids into the jejunum. Despite these theoretical benefits, there are only a few reports of PEG-J being used to palliate GOO.18,19 Like SEMS placement, this technique offers the advantage of immediate symptom relief, and furthermore, PEG-J is a procedure that can be performed by most gastrointestinal endoscopists. In this study, we demonstrated that patients who underwent SEMS placement for malignant GOO had a substantially longer median time to device failure or death as compared to those who underwent PEG-J (70 vs. 35 days). While these results showed that patients who received SEMS did better, these data are somewhat limited by our retrospective design and relatively small sample size. Furthermore, the issue of selection bias must also be considered, as in other reports sicker patients were assigned to PEG-J.12

In our study, we attempted to address the potential for physicians' selection bias by examining baseline characteristics that might influence survival. These variables included: age, performance status (WHO/ECOG), primary tumor type, presence of lymph node or metastatic disease at inclusion, and the nature of any preceding cancer therapy. The ECOG score has been used to predict survival in patients with esophageal and pancreatic cancers.20,21 Furthermore, performance status has been shown in two separate studies to be the single most important predictor of survival in patients with malignant GOO.22,23 For each of these variables, there was no discernible difference between the two treatment arms in this study, which helps to mitigate the possibility of selection bias.

The degree of complications did not appear to be different in comparing both groups, and only three patients developed late, major complications (all were recurrent gastroduodenal obstruction). Tumor ingrowth, which is regarded as a major problem that limits the patency of uncovered gastroduodenal SEMS was only encountered in one patient (361 days after SEMS placement). No cases of cholangitis or stent migration were documented. Only one patient in the PEG-J arm developed recurrent obstructive symptoms, which was an unexpected occurrence given the venting gastrostomy. The need for re-intervention was also similar in both groups.

Overall, this study represents the largest series to date examining PEG-J placement as a palliative treatment for malignant GOO, and it is the only study to directly compare use of PEG-J to that of gastroduodenal SEMS in this group of patients. Our results indicate that gastroduodenal SEMS placement may be associated with longer aggregate device patency and survival as compared to PEG-J in this challenging patient population. Both interventions were similarly tolerated with respect to complications, and neither was associated with an increased need for re-treatment. A prospective multi-centered study would certainly help to verify these results.

Abbreviations

- GOO

gastroduodenal outlet obstruction

- GJ

gastrojejunostomy

- PEG

percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

- SEMS

self-expandable metallic stent

- SSDI

social security death index

- GOOSS

GOO Scoring System

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/jig

Conflict of Interests

Dr. Michel Kahaleh is a consultant for Boston Scientific, and he has received research funding from Boston Scientific, Mi Tech, and Xlumina. All other authors have no relevant financial relationships to disclose with respect to this article.

References

- 1.Shone DN, Nikoomanesh P, Smith-Meek MM, Bender JS. Malignancy is the most common cause of gastric outlet obstruction in the era of H2 blockers. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:1769–1770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lopera JE, Brazzini A, Gonzales A, Castaneda-Zuniga WR. Gastroduodenal stent placement: current status. Radiographics. 2004;24:1561–1573. doi: 10.1148/rg.246045033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adler DG, Baron TH. Endoscopic palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction using self-expanding metal stents: experience in 36 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:72–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05423.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Hardacre JM, Sohn TA, Sauter PK, Coleman J, et al. Is prophylactic gastrojejunostomy indicated for unresectable periampullary cancer? A prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1999;230:322–328. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00005. discussion 8–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patton JT, Carter R. Endoscopic stenting for recurrent malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Br J Surg. 1997;84:865–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong YT, Brams DM, Munson L, Sanders L, Heiss F, Chase M, et al. Gastric outlet obstruction secondary to pancreatic cancer: surgical vs endoscopic palliation. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:310–12. doi: 10.1007/s00464-001-9061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Del Piano M, Ballare M, Montino F, Todesco A, Orsello M, Magnani C, et al. Endoscopy or surgery for malignant GI outlet obstruction? Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:421–426. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02757-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maetani I, Tada T, Ukita T, Inoue H, Sakai Y, Nagao J. Comparison of duodenal stent placement with surgical gastrojejunostomy for palliation in patients with duodenal obstructions caused by pancreaticobiliary malignancies. Endoscopy. 2004;36:73–78. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mittal A, Windsor J, Woodfield J, Casey P, Lane M. Matched study of three methods for palliation of malignant pyloroduodenal obstruction. Br J Surg. 2004;91:205–209. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jeurnink SM, Steyerberg EW, van Hooft JE, van Eijck CH, Schwartz MP, Vleggaar FP, et al. Surgical gastrojejunostomy or endoscopic stent placement for the palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction (SUSTENT study): a multicenter randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:490–499. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wadiwala IM, Bacon BR. A simplified technique for constructing a feeding jejunostomy from an existing gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:288–290. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(86)71849-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schmidt C, Gerdes H, Hawkins W, Zucker E, Zhou Q, Riedel E, et al. A prospective observational study examining quality of life in patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Am J Surg. 2009;198:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gauderer MW, Ponsky JL, Izant RJ., Jr Gastrostomy without laparotomy: a percutaneous endoscopic technique. J Pediatr Surg. 1980;15:872–875. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(80)80296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeurnink SM, van Eijck CH, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD. Stent versus gastrojejunostomy for the palliation of gastric outlet obstruction: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowe AS, Beckett CG, Jowett S, May J, Stephenson S, Scally A, et al. Self-expandable metal stent placement for the palliation of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction: experience in a large, single, UK centre. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:738–744. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Telford JJ, Carr-Locke DL, Baron TH, Tringali A, Parsons WG, Gabbrielli A, et al. Palliation of patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction with the enteral Wallstent: outcomes from a multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:916–920. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02228-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dormann A, Meisner S, Verin N, Wenk Lang A. Self-expanding metal stents for gastroduodenal malignancies: systematic review of their clinical effectiveness. Endoscopy. 2004;36:543–550. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Wang Z, Ni X, Jiang Z, Ding K, Li N, et al. Double percutaneous endoscopic gastrojejunostomy tubes for decompression and refeeding together with enteral nutrients: three case reports and a review of the literature. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2009;19:e167–e170. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181badd7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vashi PG, Dahlk S, Vashi RP, Gupta D. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube occlusion in malignant peritoneal carcinomatosis-induced bowel obstruction. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:1069–1073. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834b0e2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conill C, Verger E, Salamero M. Performance status assessment in cancer patients. Cancer. 1990;65:1864–1866. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19900415)65:8<1864::aid-cncr2820650832>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steyerberg EW, Homs MY, Stokvis A, Essink-Bot ML, Siersema PD. Stent placement or brachytherapy for palliation of dysphagia from esophageal cancer: a prognostic model to guide treatment selection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:333–340. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)01587-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeurnink SM, Steyerberg EW, Vleggaar FP, van Eijck CH, van Hooft JE, Schwartz MP, et al. Predictors of survival in patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction: a patient-oriented decision approach for palliative treatment. Dig Liver Dis. 2011;43:548–552. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Hooft JE, Dijkgraaf MG, Timmer R, Siersema PD, Fockens P. Independent predictors of survival in patients with incurable malignant gastric outlet obstruction: a multicenter prospective observational study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1217–1222. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2010.487916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]