Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the Structured Interview for Tanning Abuse and Dependence (SITAD).

Design

Longitudinal survey.

Setting

College campus.

Participants

A total of 296 adults.

Main Outcome Measures

The SITAD modified items from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders that focus on opiate abuse and dependence. Indoor tanning (IT) behavioral patterns and opiate-like reactions to tanning were measured, and IT behavior was measured 6 months later.

Results

Of 296 participants, 32 (10.8%) met the SITAD criteria for tanning abuse (maladaptive pattern of tanning as manifested by failure to fulfill role obligations, physically hazardous tanning, legal problems, or persistent social or interpersonal problems) and 16 (5.4%) for tanning dependence as defined by 3 or more of the following: loss of control, cut down, time, social problems, physical or psychological problems, tolerance, and withdrawal. The IT frequency in dependent tanners was more than 10 times the rate in participants who do not meet the SITAD criteria for tanning abuse or dependence. Tanning-dependent participants were more likely to report being regular tanners (75%; odds ratio, 7.0). Dependent tanners scored higher on the opiate-like reactions to tanning scale than did abuse tanners, who scored higher than those with no diagnosis.

Conclusions

The SITAD demonstrated some evidence of validity, with tanning-dependent participants reporting regular IT, higher IT frequency, and higher scores on an opiate-like reactions to tanning scale. A valid tanning dependence screening tool is essential for researchers and physicians as a tanning-dependent diagnosis may facilitate a better understanding of tanning motivations and aid in the development of efficacious intervention programs.

Recent research has explored the idea that some patterns of tanning behavior may be dependent1–7 by using a common alcohol screening questionnaire, the CAGE,8 or, alternatively, by adapting criteria for substance-related disorders from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition, Text Revision) (DSM-IV-TR)9 modified to reflect UV light tanning (ie, sunbathing or indoor tanning [IT]).1,4,6,7 Whereas data from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse10 report prevalence rates for alcohol and any illicit drug combined as 2.6% to 9.3%, the modified CAGE and modified DSM report tanning dependence rates ranging from 12% to 55%.1,4,6,7,11 Prevalence rates for dependence on alcohol and various drugs do differ. However, even in settings enriched for dependent behavior, such as bars,12 prevalence rates are not nearly as high as the tanning dependence rates reported. The high prevalence rates reported suggest that the current assessments tend to overidentify tanning dependence.

Feldman and others suggest that the mechanism for tanning dependence is most likely the release of endogenous opioids when the skin is exposed to UV radiation (see Nolan and Feldman5 for a review). It is probable that exploring tanning behavior by following the approach used in the DSM-IV-TR to categorize opioid use behaviors will lead to improved accuracy in the categorization of tanning dependence.

The Structured Interview for Tanning Abuse and Dependence (SITAD) is a tanning dependence assessment based on opioid use items adapted from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID).13 The use of modified opioid SCID items was chosen specifically for good content and face validity in the measure. The self-administered structured interview format was chosen because this format has been demonstrated to achieve valid psychiatric categorization for opioid dependence in a previous study.14

Evaluation of the SITAD involved exploring differences in variables (ie, IT frequency, IT behavioral patterns, and scores on a scale measuring opiate-like reactions to tanning) that would theoretically be expected to differ among individuals exhibiting tanning abuse, those with tanning dependence, and those who do not meet the SITAD criteria for tanning abuse or dependence. We also expect that use of the SITAD will result in lower prevalence rates for tanning dependence than have been reported in previous studies.1,6,7

METHODS

RECRUITMENT AND SAMPLE

This study was conducted at East Tennessee State University between October 1, 2008, and May 31, 2009, and received approval from the university’s institutional review board human subjects committee before initiation. The participants were 325 college students (mean [SD] age, 21.8 [5.85] years). The sample was 64.5% female (35.5% male) and 88.9% single (11.1% married). Skin type was distributed as follows: I = 10.5%, II = 23.3%, III = 32.8%, IV = 24.3%, V = 8.1%, and VI = 1.0%.

PROCEDURES

Of 360 randomly selected students contacted by e-mail, 325 agreed to participate (90% participation rate). Twenty-nine individuals who completed the baseline measure did not complete the 6-month behavioral assessment follow-up, leaving 296 participants with complete data. Alter signing informed consent documents, participants completed the SITAD in the fall (ie, October and November). They also completed items assessing their age, sex, and skin type. Whether participants have ever engaged in IT, the age of their first IT experience, their IT pattern,15 and whether they experience opiate-like responses to tanning were also assessed in the fall. Six months later, at the end of spring (ie, April and May), participants were reassessed for their IT use in the previous 6 months, thus assessing the period of highest IT frequency.16

MEASURES

The SITAD

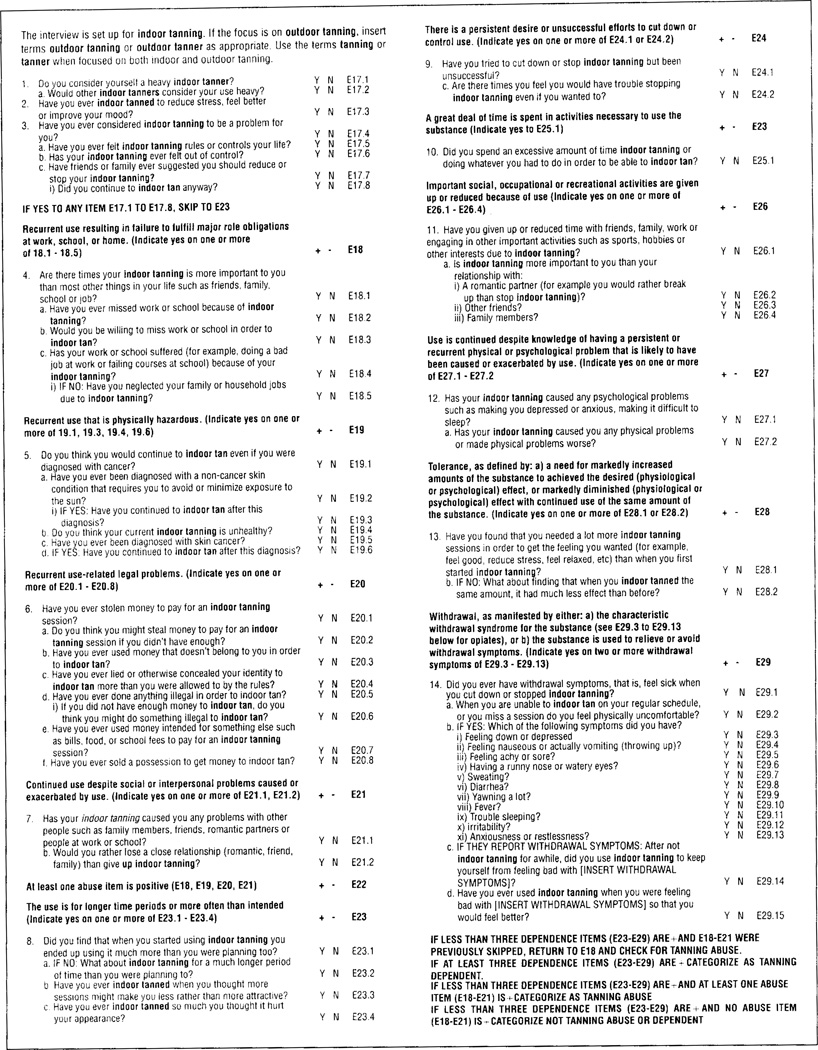

The SITAD (Figure) used the SCID13 as a model for self-administered interview items designed to determine whether individuals met the criteria for tanning abuse or dependence. Specifically, it focused on criteria related to opiate abuse and dependence. Interview questions were modified to reflect tanning abuse and dependence features and were presented as a computer-assisted self-administered interview with conditional logic (skip patterns, etc). Modification of the SCID criteria and SCID items into criteria and items appropriate to tanning was accomplished through consultation with substance abuse experts, focus groups with tanners, and pretesting that included cognitive interviewing.2,17 Initially, the SCID items for opiate abuse and dependence were modified using a panel of substance abuse and skin cancer prevention experts. These items were then evaluated using focus groups of tanners to ensure that the items were directly relevant to the unique experiences of individuals who tan. Last, the items were tested using in-person cognitive interviewing to assess for clarity, specificity, recall, and appropriateness of wording. The SITAD can be used with sunbathing, IT, or both behaviors combined by using wording specific to the behavior(s). Participants respond yes or no to the items, with a yes answer indicating that they endorse the criterion.

Figure.

The Structured Interview for Tanning Abuse and Dependence.

To be categorized as tanning dependent, participants had to meet 3 or more of the following criteria: (1) loss of control, tanning is engaged in more often or for longer periods than intended; (2) cut down, a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control tanning; (3) time, a great deal of time is spent obtaining, using, or recovering from tanning; (4) social problems, important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced due to tanning use; (5) physical or psychological problems, tanning use despite knowledge of physical or psychological problems caused or exacerbated by tanning; (6) tolerance, the need for increased amounts of tanning to achieve an opiate-like effect or diminished effects with continued use of the same amount of IT; and (7) withdrawal, maladaptive behavioral, physiologic, and cognitive changes specific to opiate withdrawal that occur with decreased tanning use; alternatively, withdrawal can manifest as continued use of tanning to avoid or relieve the physical and cognitive symptoms associated with decreased use.

A tanning abuse diagnosis was determined if the participants did not meet at least 3 of the criteria for tanning dependence as described previously herein but manifested 1 (or more) of the following criteria: (1) recurrent tanning resulting in failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home; (2) recurrent tanning that is physically hazardous; (3) recurrent tanning-related legal problems; and (4) continued tanning despite persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused or exacerbated by the behavior.

IT Behavioral Patterns

Patterns of IT were assessed by giving respondents descriptions of various patterns (ie, event/episodic, regular seasonal, regular year-round, and mixed) and asking them to rate whether their behavior matches these descriptions on 5-point Likert-type scales. Individuals are classified into 1 of 3 general patterns (ie, event, mixed, or regular) using an algorithm.17 Regular tanners report tanning consistently across the year and going to the tanning salon weekly. Event tanners report using IT to prepare for specific events (eg, prom, the beach, or a wedding). Those with a mixed pattern typically report regular tanning in 1 or 2 seasons (eg, winter and spring) with occasional tanning for events outside those seasons. These patterns differ in terms of IT frequency, IT history, and IT psychosocial predictors.

IT Behavior

Frequency of IT was measured 6 months after the presentation of the other survey items by asking participants to estimate the number of times they used IT in the previous 6 months. The 6-month time frame used (December to May) coincides with the period of heaviest IT behavior.16 This open-ended measure of IT use has demonstrated strong correlations with diary measures of IT behavior over the same time frame in other studies (r = 0.77–0.87, P < .001).18

Opiatelike Reactions to Tanning

Opiatelike reactions were measured using a 4-item scale from an earlier study.19 The items were based on the typical physical reactions reported with endogenous opiate release (ie, relaxation, pain relief, stress relief, and sense of well-being or euphoria). This scale evidenced excellent internal reliability estimates (Cronbach α = .90).

RESULTS

Test-retest reliability for the SITAD was evaluated in a group distinct from the main study group (n = 91) by administering the measure 2 times separated by 3 weeks. Test-retest reliability was good for the IT dependence diagnosis, with 97% agreement between the 2 administrations (phi coefficient = 0.84). Although the agreement for the IT abuse diagnosis was reasonably high (84%), the reliability estimate was relatively low (phi coefficient = 0.43).

PREVALENCE RATES

Thirty-two participants (10.8%) met the SITAD criteria for tanning abuse and 16 (5.4%) met the criteria for tanning dependence. These rates of substance-related dependence are similar to past-year prevalence rates for other forms of substance abuse and dependence found in national surveys (eg, 5.8% for alcohol dependence and 7.7% for alcohol or any illicit drug dependence in young adults) and lower than previously reported rates using other measures.

CONSTRUCT VALIDITY

We used analysis of variance to test for differences in IT frequency and opiatelike reactions to tanning. Statistically significant differences were found for IT frequency in the past 6 months (Table 1). Dependent tanners reported a significantly higher IT frequency than did abuse tanners, who reported a higher frequency than those not categorized as either dependent or abuse tanners (F2,293 = 72.6, P < .001). The IT frequency in dependent tanners was more than 10 times the rate in participants not categorized as dependent or abuse tanners and more than 3 times the rate in abuse tanners. Significant differences were also found for scores on the opiatelike reactions scale, with dependent tanners reporting higher scores than abuse tanners, who scored higher than those not categorized as dependent or abuse tanners (F2,293 = 34.1, P < .001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Indoor Tanning Frequency and Opiatelike Reactions Scale Scores by Tanning Dependence Diagnosisa

| Variable | No Diagnosis (n=248) |

Tanning Abuse (n=32) |

Tanning Dependence (n=16) |

F2,293 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indoor tanning uses in past 6 mo, mean (SD), No. | 4.6 (10.8) | 15.9 (10.8) | 50.6 (48.7) | 72.6 |

| Opiatelike reactions scale score, mean (SD) | 8.7 (4.3) | 12.9 (4.0) | 16.3 (2.7) | 34.1 |

P < .001 for both variables.

We also examined the relationship of tanning dependence diagnosis with IT behavioral pattern. Participants who were categorized as tanning dependent were more likely to report being regular tanners (, P < .001) (Table 2). As seen in Table 2, 75% of participants categorized as tanning dependent reported being regular tanners (odds ratio, 7.0), with 94% reporting being either mixed or regular tanners.

Table 2.

Indoor Tanning Patterns by Tanning Dependence Diagnosisa

| Participants, No. (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Nontanners | Event Tanners | Mixed Tanners | Regular Tanners | Total |

| No diagnosis | 137 (55) | 63 (25) | 31 (13) | 17 (7) | 248 |

| Tanning abuse | 0 | 13 (41) | 6 (19) | 13 (41) | 32 |

| Tanning dependence | 0 | 1 (6) | 3 (19) | 12 (75) | 16 |

| Total | 137 | 77 | 40 | 42 | 296 |

, P < .001.

COMMENT

This study adds to the increasing evidence that some forms of tanning behavior reflect dependence. The measure evaluated herein, the SITAD, demonstrates reasonable tanning dependence prevalence rates. It also exhibits evidence of construct validity, with relationships to tanning frequency, tanning patterns, and a measure of opiate-like reactions to tanning in the expected directions. The test-retest reliability of the tanning dependence classification was good. However, the reliability of the tanning abuse classification was not strong, indicating the need to further study and refine it. Although there is as yet no gold standard for categorizing tanning dependence, and a valid diagnosis will require sets of criteria symptoms that can be assessed through face-to-face clinical interview and medical record review, the SITAD constitutes a further advance in clarifying and confirming this classification.

Earlier approaches to categorizing tanning dependence relied on modified screening measures with no clear underlying conceptual model. The SITAD was adapted from a standard format used to make valid DSM diagnoses and was based on Feldman’s conceptualization of tanning dependence as it related to endogenous opioid release from UV radiation exposure. Furthermore, the SITAD development used an empirical screening and evaluation process to ensure that the items were directly relevant to the unique experiences of individuals who tan. This careful, empirical approach resulted in a measure with good face and content validity that seems to also perform well in identifying individuals likely experiencing dependence to the effects of tanning behavior. This measure could provide a reasonable quasi-gold standard for tanning dependence, at least until the construct is more fully conceptualized and defined.

This study evaluated a limited sample, that is, college-aged participants. However, college students represent one of the highest risk groups for skin cancer, reporting high frequencies of intentional tanning, particularly IT.20 There has also been no evidence of differential skin cancer risk behaviors between college and noncollege populations.21–23 There is no current gold standard of tanning dependence diagnosis against which to validate this or other measures in the literature. Future work needs to develop an accepted conceptual model of pathologic tanning and criteria sets of symptoms that can be assessed through clinical interview and medical record review. These results need to be replicated in a larger, broader, and more representative sample. They should also be replicated examining outdoor tanning behavior and with younger and older populations. An important limitation is that this measure should be compared with the existing modified CAGE and modified DSM screening measures to more clearly understand how they relate conceptually and empirically.

Understanding influences on tanning decisions will be important in reducing and eliminating risky tanning behavior. Recent evidence suggests that dependence motivations may be important factors in tanning behaviors, particularly for individuals with frequent and persistent tanning habits.4,5,9,11,12 A measure, such as the SITAD, that more accurately identifies tanners who are experiencing tanning dependence will be important for physicians to better understand the influences on their patients’ tanning behaviors. For example, a patient experiencing tanning dependence will have his or her tanning decisions strongly affected by aspects of the dependency in addition to the effects of appearance or health motivations that may be present. Such an individual may be less influenced by health or appearance-based messages designed to reduce his or her tanning motivations. Other intervention strategies that affect the dependency aspects of his or her behavior may need to be explored and developed. Use of the SITAD to validate simple, short screening measures will also be important.

If some tanners do, in fact, become addicted to tanning, there may be policy implications as well. The IT industry uses unlimited tanning packages and attractive models to hook tanners into tanning.24 Many of these strategies are directed at minors. Given the association of tanning bed use with melanoma morbidity, stronger policy on the marketing of and access to tanning beds for minors should be considered if addiction can be substantiated. The SITAD will prove to be a useful tool in further exploring tanning dependence in this context.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This research was supported by grant 5R21CA116384-2 from the National Cancer Institute (Dr Hillhouse).

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Hillhouse had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Hillhouse, Shields, and Longacre. Acquisition of data: Hillhouse, Turrisi, Shields, and Longacre. Analysis and interpretation of data: Hillhouse, Baker, and Stapleton. Drafting of the manuscript: Hillhouse, Baker, and Stapleton. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Hillhouse, Baker, Turrisi, Shields, Stapleton, Jain, and Longacre. Statistical analysis: Hillhouse and Stapleton. Obtained funding: Hillhouse and Turrisi. Administrative, technical, and material support: Hillhouse, Baker, Turrisi, Shields, Jain, and Longacre. Study supervision: Hillhouse.

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heckman CJ, Egleston BL, Wilson DB, Ingersoll KS. A preliminary investigation of the predictors of tanning dependence. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32(5):451–464. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.5.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hillhouse J, Abbott K, Hamilton J, Turrisi R. This (tanning) bed’s for you: addictive tendencies in intentional tanning. Poster presented at: Western Psychological Association Annual Meeting; April 30– May 4, 2003; Vancouver, BC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keen SB, Yelverton CB, Rapp SR, Feldman SR. UV light abuse as a substance-related disorder: clinical implications. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(8):1047–1048. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.8.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mosher CE, Danoft-Burg S. Addiction to indoor tanning: relation to anxiety, depression, and substance use. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(4):412–417. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nolan BV, Feldman SR. Ultraviolet tanning addiction. Dermatol Clin. 2009;27(2):109–112, v. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poorsattar SP, Hornung RL. UV light abuse and high-risk tanning behavior among undergraduate college students. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(3):375–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warthan MM, Uchida T, Wagner RF., Jr UV light tanning as a type of substance-related disorder. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141(8):963–966. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.8.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayfield D, McLeod G, Hall P. The CAGE questionnaire: validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131(10):1121–1123. doi: 10.1176/ajp.131.10.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Accessed October 30, 2011];National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. 2010 http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k10NSDUH/2k10Results.htm. [PubMed]

- 11.Harrington CR, Beswick TC, Leitenberger J, Minhajuddin A, Jacobe HT, Adinoff B. Addictive-like behaviours to ultraviolet light among frequent indoor tanners. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36(1):33–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03882.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trocki K, Drabble L. Bar patronage and motivational predictors of drinking in the San Francisco Bay Area: gender and sexual identity differences. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;(suppl 5):345–356. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2008.10400662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute Biometrics Research Department; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kranzler HR, Kadden RM, Babor TF, Tennen H, Rounsaville BJ. Validity of the SCID in substance abuse patients. Addiction. 1996;91(6):859–868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiilhouse J, Turrisi R, Shields AL. Patterns of indoor tanning use: implications for clinical interventions. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143(12):1530–1535. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.12.1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shields A, Hillhouse J, Longacre H, Benfield N, Longacre I, Bruner C. Characterizing indoor tanning behavior using a timeline followback assessment strategy. Poster presented at: 40th Annual Convention for the Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; November 16–19, 2006; Chicago, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Longacre I, Hillhouse J, Shields A, Visser P, Longacre H, Bruner C. Tanning-Related Behavioral Pathology. Chicago, IL: Association for Behavioral and Cognitive Therapies; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Hamilton J, Glass M, Roberts P. Electronic diary assessment of UV-risk behavior. Poster presented at: Society of Behavioral Medicine Annual Meeting; April 13–16, 2005; Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hillhouse J, Turrisi R, Stapleton J, Robinson J. Effect of seasonal affective disorder and pathological tanning motives on efficacy of an appearance-focused intervention to prevent skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(5):485–491. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis KJ, Cokkinides VE, Weinstock MA, O’Connell MC, Wingo PA. Summer sunburn and sun exposure among US youths ages 11 to 18: national prevalence and associated factors. Pediatrics. 2002;110(1, pt 1):27–35. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boldeman C, Bränström R, Dal H, et al. Tanning habits and sunburn in a Swedish population age 13–50 years. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(18):2441–2448. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00310-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cokkinides VE, Johnston-Davis K, Weinstock M, et al. Sun exposure and sun-protection behaviors and attitudes among U.S. youth, 11 to 18 years of age. Prev Med. 2001;33(3):141–151. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2001.0877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koh HK, Bak SM, Geller AC, et al. Sunbathing habits and sunscreen use among white adults: results of a national survey. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(7):1214–1217. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.7.1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freeman S, Francis S, Lundahl K, Bowland T, Dellavalle RP. UV tanning advertisements in high school newspapers. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142(4):460–462. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.4.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]