Abstract

Effectiveness of nanomedicines in cancer therapy is limited in part by inadequate delivery and transport in tumor interstitium. This report reviews the experimental approaches to improve nanomedicines delivery and transport in solid tumors. These approaches include tumor vasculature normalization, interstitial fluid pressure modulation, enzymatic extracellular matrix degradation, and apoptosis-inducing tumor priming technology. We advocate the latter approach due to its ease and practicality (accomplished with standard-of-care chemotherapy such as paclitaxel) and tumor selectivity. Examples of applying tumor priming to deliver nanomedicines and to design drug/RNAi-loaded carriers are discussed.

Keywords: Nanomedicine, Nanotechnology, Vasculature Normalization, Interstitial Fluid Pressure, Extracellular Matrix, Tumor Priming, Apoptosis, Paclitaxel, Tumor-Penetrating Microparticles, RNAi

INTRODUCTION

Nanomedicines (NM) are broadly defined as nano-sized entities used in the treatment, diagnosis, monitoring and control of biological systems (1,2). NM comprises macromolecules (e.g., proteins, antibodies), molecular bioconjugates (e.g., polymer bioconjugates), viral vectors, and nanoparticulate carriers (e.g., liposomes, micelles, and polymeric nanoparticles) with size and shape in the nanoscale range (1–1000 nm). Often times macromolecules are used to coat NM to achieve special properties such as targeting the cell surface ligands and promoting internalization (3). NM are used to (a) improve the solubility of hydrophobic compounds (e.g., paclitaxel albumin nanoparticles (4)), (b) protect a molecule from undesirable interaction with biological components and improve its stability (e.g., liposomal SN-38 (5)), (c) provide sustained and controlled release of therapeutic molecules (e.g., cisplatin-loaded glycol chitosan nanoparticles (6)), (d) favorably alter the pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of pharmacologically active agent (e.g., doxorubicin immunoliposome (7)), (e) overcome impermeable transport barriers (e.g., hexapeptide dalargin nanoparticles that infiltrate the blood brain barrier (8)), (f) overcome drug resistance (e.g., solid lipid nanoparticles to overcome efflux-mediated resistance (9)), and (g) improve cellular internalization of negatively-charged nucleotides (e.g., cationic vectors for siRNA and DNA delivery (10)). Potential target sites in cancer are tumor interstitium (e.g., diagnostics or therapeutics), cell membrane (e.g., antibodies), or intracellular compartments (e.g., DNA, antisense, RNAi).

The utility of cancer NM depends on successful delivery to individual tumor cells in vivo. The common barriers for NM delivery to blood-borne cancers (e.g., leukemia) and solid tumors are degradation in blood (e.g., chemical instability of the carrier, degradation of siRNA by the omnipresent nucleases), surface opsonization and subsequent entrapment by the mononuclear phagocytic system and reticuloendothelial system (RES), and rapid renal clearance (e.g., for small NM with <6 nm diameter) (11). In general, these problems are related to the physiochemical properties of NM and can be overcome by optimizing particle size, surface charge, and surface modifications such as pegylation. Readers are referred to several excellent recent reviews on this subject (12,13,14).

For solid tumors, which constitute about 85% of human cancers, the delivery of NM from injection sites to tumor cells involves transport by the systemic blood to tumors, extravasation from tumor vasculatures, and transport in tumor interstitium. The major transport mechanisms are diffusion and convection, whereas transcytosis plays a minor role (15). There are notable barriers to each of these processes. Factors affecting these processes are described in several recent reviews (16,17).

The focus of the present review is on extravasation and interstitial transport. Table 1 summarizes the experimental approaches that manipulate these processes to improve the delivery and transport of NM in solid tumors. These approaches include modulation of intra-tumor pressure gradients, tumor vasculature normalization, enzymatic degradation of extracellular matrix (ECM), and chemotherapy-induced tumor priming (18). The tumor priming method is developed in part based on our initial observations in mid-1990s that standard cytotoxic chemotherapeutics, by inducing apoptosis, transiently expand the interstitial space for several days and thereby promote the transport of NM in tumor interstitium within this time window. The apoptosis-inducing tumor priming concept has further provided the basis for the development of drug-loaded tumor-penetrating polymeric microparticles administered by regional therapy to treat bulky peritoneal tumors, liposomal NM delivery administered by intravenous injection to treat subcutaneous xenograft tumors, and our more recent efforts in developing RNAi carriers. Our group advocates the tumor priming approach because it can be readily achieved by using the standard-of-care chemotherapy and does not require additional treatments; we have extended this concept to develop multi-component carriers that penetrate tumor interstitium.

Table 1.

Experimental approaches to enhance interstitial nanomedicine transport in solid tumors.

| Approaches | Vasculature normalization and IFP modulation | Enzymatic ECM degradation | Apoptosis-inducing tumor priming |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advantages |

|

|

|

| Limitations |

|

|

|

| Examples of successful applications |

Oncolytic herpes simplex virus, HSV; vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, VEGFR; extracellular matrix, ECM; interstitial fluid pressure, IFP; nanomedicine, NM.

BARRIERS TO NANOMEDICINE DELIVERY TO SOLID TUMOR

Barriers to blood-to-tumor-transport and extravasation in solid tumors

Compared to normal tissues, tumors have poorly organized, tortuous and defective vasculatures with substantial location-dependent heterogeneity; the net effect is a greater flow resistance and lower blood flow, and consequently lower presentation of NM to tumors. On the other hand, tumor blood vessels have discontinuous endothelium, and are leakier and more permeable, with much larger pore size (ranging from 100 to 780 nm) compared to vessels in most normal tissues (<6 nm pores in postcapillary venules; the exceptions are renal glomeruli and the hepatic/splenic sinusoidal endothelium that have respective pore sizes of 50 and 150 nm). These properties are favorable for extravasation of NM via diffusion and convection (due to transvascular fluid flow) in tumors, and enable passive tumor targeting using larger NM (e.g., 100 nm).

The lymphatic system, which enables the drainage of particulates and interstitial fluid into the blood circulation, is impaired in solid tumors. This defect decreases the clearance and enhances the retention of macromolecules and NM in tumor interstitium. This effect, coupled with the leaky tumor vessels, results in the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) in tumors. The absence of lymphatic drainage also increases the interstitial fluid pressure (IFP), which in turn reduces the hydraulic conductivity and fluid flow and consequently reduces the convective extravasation and interstitial transport.

Approaches to improve the blood-to-tumor-transport and extravasation include modulation of microvascular fluid pressure (MVP) and IFP, and tumor vasculature normalization. Elevating MVP by angiotensin II improves the extravasation, tumor-selective accumulation and efficacy of small- and macromolecular drugs (19,20,21). Angiotensin II was first evaluated in patients nearly 30 years ago, but has not been widely used probably because it induces systemic hypertension. A more recent study shows that angiotensin-induced hypertension enhances the delivery and efficacy of a polymer-drug conjugate (neocarzinostatin with styrene/maleicacid copolymers) in patients with cholangiocarcinoma, and liver, kidney and pancreatic cancers (21). Approaches to lower tumor IFP include physical methods (e.g., hyperthermia), chemical methods (osmotic agent mannitol), enzymatic degradation of ECM (e.g., collagenase, hyaluronidase), and pharmacological treatments (e.g., tumor necrosis factor-α, paclitaxel, radiation) (15). For example, applying hyperthermia locally to subcutaneous tumors improves the extravasation and accumulation of intravenously administered liposomes and gene vectors (up to 400 nm diameter) (22,23).

Tumor blood vessel normalization was first achieved with ICRF-159 (topoisomerase II inhibitor) (24), and more recently with anti-angiogenic agents. The normalized vasculature is less permeable, less dilated, less tortuous, and shows more normal basement membrane and greater pericytes coverage. These changes are associated with decreased IFP and increased tumor oxygenation (25,20). Normalization by an inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor II (DC101) promoted the extravasation of albumin (20). A similar approach using pazopanib, a multi-targeted inhibitor of VEGF and platelet-derived growth factor receptors (8-daily treatments), reduced tumor IFP and vessel density in human xenograft tumors. However, pazopanib did not improve the overall delivery of a larger NM, i.e., Doxil® (liposomal doxorubicin, 85 nm size) and instead reduced its transport in tumor interstitium (26). Benefits from normalization are transient, lasting for 2 to 5 days, after which time the tumor blood vessel density significantly drops due to vascular cell apoptosis (25,27,28); prolonged anti-angiogenic treatment causes vascular regression and compromises drug delivery (29). These observations indicate the dynamic interplay between tumor vasculature, IFP and other tumor microenvironmental parameters, suggesting the need of fine-tuning the tumor vascularization for therapeutic gains, especially when vascular normalizationdrugs are used in combination with other drugs including NM.

Approaches to improve extravasation include the use of vasodilators such as nitric oxide-release agents (30) and nitroglycerin. Topical application of nitroglyercin to the skin overlaying subcutaneous tumors in mice enhances the tumor delivery of intravenously administered macromolecules (i.e., Evans blue/albumin complex, 6 nm) by 2- to 3-fold and enhances the efficacy of small molecules (aclarubicin, 812 Da) or PEG-conjugated zinc protoporphyrin IX (110 kDa) (31). Topical nitroglycerin also enhances the therapeutic efficacy of vinorelbine, cisplatin, docetaxel and carboplatin in lung cancer patients (32,33).

Barriers to transport in stumor interstitium

Interstitial transport of NM, due to its relatively large size, is mainly by convection that depends on hydraulic conductivity and pressure gradient, whereas small molecules (e.g., drug released from NM) are mainly transported by diffusion. Within the interstitium, extracellular matrix (ECM) or stroma, which provides the structural support, poses barriers to NM transport (34,35). ECM proteins such as collagens, glycosaminoglycans, preoteoglycans, fibrous proteins and glycoproteins, by presenting physical obstacles or by binding to NM, lower the interstitial transport of NM (36,37). In addition, the fibrotic stroma in pancreatic cancer activates the hedgehog signaling and inhibits the formation of blood vessel resulting in sparse vasculature that is only partially functional (38,39). Approaches to improve interstitial transport include enzymatic degradation of ECM, promoting transcytosis, and using tumor-penetrating peptides.

APROACHES TO IMPROVE INTERSTITIAL TRANSPORT

Enzymatic degradation of extracellular matrix

Degradation of ECM macromolecules using enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases (e.g., collagenases, stromelysins, gelatinases and elastases), hyaluronidase and cathepsin C (digesting decorin), improves the intra-tumoral dispersion of NM including monoclonal antibody, liposomal doxorubicin, 10–500 kDa dextran, albumin, IgG, and herpes simplex virus or HSV, possibly due to reduced IFP and enhanced extravasation (40,41,36,42,43,44,42,37,45). The increase in HSV tumor penetration is sufficient to enhance its efficacy in xenograft tumors (41,46). Coating of nanoparticles (upper size limit of 100 nm) with collagenase yielded a 4-fold higher penetration/accumulation in the core of multicellular spheroids (47). Earlier clinical studies suggest that hyaluronidase, given in combination with chemotherapy, does not pose significant normal tissue toxicity (48,49,50). However, the clinical utility of enzymatic ECM degradation is uncertain, because (a) elevated interstitial collagenase levels are associated with a poor patient prognosis in a variety of cancers (51,52), (b) ECM degradation may promote cancer progression, invasion and metastasis (53,51), (c) the substantial heterogeneities in tumor microenvironment and ECM composition make it difficult to select the type and the optimal dose of enzymes, (d) the acidic microenvironment in solid tumors may diminish enzyme activity (45,54), and (e) ECM digestion will not expand the intercellular space between neighboring tumor cells (typically about 20 nm) and therefore may not be useful for larger NM (55,56).

Promoting transcytosis

Albumin-bound paclitaxel nanoparticles (Abraxane®, 130 nm) bind to albumin receptor (gp60) on endothelial cell membrane and undergo caveolae-mediated transcytosis across the endothelium (57). The presence of an albumin-binding glycoprotein in tumors, SPARC (secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine), enhances the Abraxane®/paclitaxel accumulation in xenograft tumors (57) and correlates with the antitumor activity of Abraxane® in patients with head and neck (58), pancreatic (59) and breast cancers (60).

Tumor-penetrating peptides

iRGD, a tumor-penetrating peptide, upon binding to αv integrins expressed on the endothelial and cancer cells, undergoes proteolytic cleavage by cell surface-associated protease to produce the CendR element that binds to neuropilin-1 and thereby triggers neuropilin-1-dependent vascular and tissue penetration (61,62,63,64). Conjugation to iRGD enhances tumor-specific delivery of the imaging agent superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoworms (about 80 nm long and 30 nm thick), and coating of Abraxane® (130 nm albumin-coated paclitaxel nanocrystals) with iRGD results in 8- to 10-fold higher drug levels and greater activity in xenograft tumors. Coadministration with iRGD as a separate entity also improves the delivery and therapeutic index of drugs and NM with diverse structures, compositions and particle size, i.e., small molecule (doxorubicin), monoclonal antibody (trastuzumab), and nanoparticles (Abraxane® and doxorubicin liposomes) in mice bearing multiple types of human xenograft tumors (62). In view of its broad spectrum activity, iRGD peptide, if shown to be safe in humans, represents an interesting and potentially fruitful approach.

Apoptosis-inducing tumor priming

Our laboratory has been studying the barriers and mechanisms of drug/NM transport and delivery in solid tumors. Through a series of in vitro and in vivo studies, we have demonstrated that tissue composition and architecture, tumor cell density and interstitial space are the key determinants of the rate and extent of drug/NM penetration in solid tumors (65,66,18,15,67,68,69). The findings from these studies have led to the development of the tumor priming technology, i.e., using apoptosis-inducing pretreatment with conventional cytotoxic chemotherapy to expand the interstitial space and thereby promote the delivery and interstitial transport of large molecules and NM in tumors. These studies further provide the basis for the development of drug-loaded tumor-penetrating polymeric microparticles to treat bulky peritoneal tumors and for our more recent efforts in developing RNAi carriers; both approaches use drugs or biocompatible materials that have good safety records in humans and are approved for human use. Our major findings are summarized below.

To understand the barriers to drug/NM transport in solid tumors, we first compared the accumulation kinetics of protein-bound drugs (e.g., paclitaxel, doxorubicin, with 50–98% plasma protein binding) in histocultures of tumor fragments (~1 mm3) and in monolayer cultures of the same tumors (68,70). This system retains the three-dimensional (3D) multicellular architecture and tissue composition (e.g., stromal tissue) as in in vivo tissues. In addition, because drug diffusion through the collagen gel was relatively rapid (half-life of <15 min) and because there was no blood flow or convection, the studies specifically addressed the rate-limiting steps in diffusional transport. The results show that the differences between monolayer and 3D cultures are mainly quantitative, i.e., the monolayer cultures show a 10-times more rapid uptake rate (uptake half-life of <2 h versus >20 h) and a 2- to 20-times higher accumulation. These differences indicate that there are factors specifically related to the 3D tumor structures or compositions that determine the drug penetration and accumulation in solid tumors.

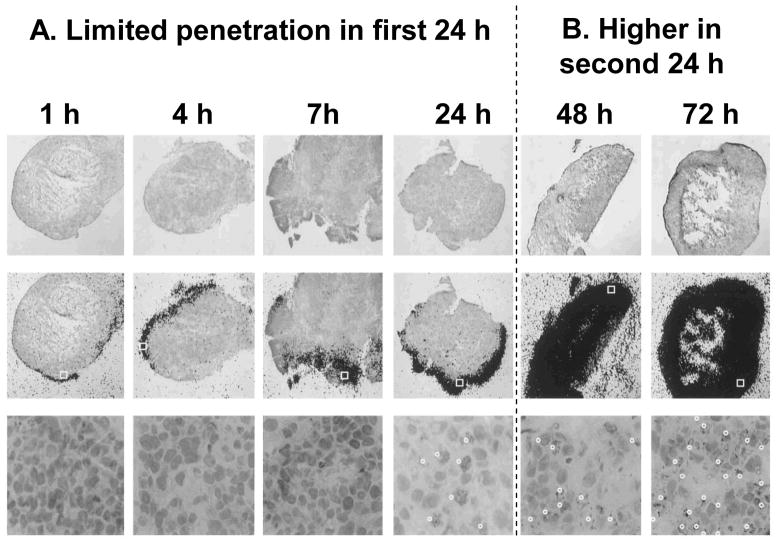

Next, we compared the penetration and accumulation of paclitaxel in histocultures of animal xenograft and human patient tumors, and found more rapid and greater uptake in patient tumors (67,66,68,69). This difference (50–100%) was not due to mdr1 p-glycoprotein expression. Additional autoradiography results revealed different transport rates, i.e., limited drug penetration in the periphery of xenografts after 24 hr (Figure 1A) vs even distribution in patient tumors. An unexpected observation was the abrupt acceleration in drug transport between 24 and 48 h in xenograft tumors, from a slow penetration rate (10–15 cell layers) in the first 24 h to a much more rapid rate (>70 cell layers) in the second 24 h (Figures 1A vs 1B). Subsequent microscopic inspections of tumors established the higher tumor cell density and tumor-to-stroma ratio in xenograft tumors. This finding, in view of the known quantitative relationships between diffusion coefficient of a molecule with interstitial space (ψ) and tortuosity (T) in a gel structure, as shown in Equation 1 (71), indicated that drug penetration into tumor tissue is highly dependent on the tissue structure and tissue composition, and further suggested the abrupt change in transport kinetics at 24 h was due to a time-dependent change in tumor structure/composition caused by the paclitaxel-induced apoptosis that occurs with a 24 h lag time (72,73,74,75,76,77,78).

Figure 1. Time course of paclitaxel penetration in FaDu xenograft tumor histocultures.

Histocultures of FaDu tumor were treated with 120 nM [3H]paclitaxel. Note changes in the kinetics during the first and second 24 h. Top: Histologic images (stained with hematoxylin and eosin), Magnification, 25×. Middle: images of autoradiographic film overlaid on histologic images, Magnification, 25×. Bottom: enlargement of the indicated boxed region of the slide in the middle panel, to demonstrate the presence of apoptotic cells (indicated by white dots), Magnification, 400×. The fractions of apoptotic cells were ~30% and ~50% at 24 and 72 h, respectively. Reproduced with permission (68).

| Equation 1 |

As apoptosis is a pharmacodynamic property that depends on the drug concentration and usually occurs after a lag time, we surmised that tumor priming (and hence the priming-enhanced transport/delivery) is dependent on the apoptosis-inducing treatment schedule such as dose intensity and frequency. We tested this hypothesis in a series of in vitro and in vivo studies. The in vitro studies used 3D tumor histocultures to compare two paclitaxel concentrations that differed in their ability to induce apoptosis; the results showed only the apoptosis-inducing concentrations (50 nM), but not the lower concentrations (10 nM), resulted in significant expansion of interstitial space and abrupt increase in drug penetration at 24 h (Figure 2) (66). Similar time- and concentration-dependent penetration property was observed with another highly protein-bound drug capable of inducing apoptosis, i.e., doxorubicin. We found that the rate of doxorubicin penetration into 3-dimensional tumor histocultures increased abruptly after treatment with high, apoptosis-inducing drug concentrations, but not after treatment with lower concentrations (69). Similarly, fractionation of a dose into two smaller doses (with one dose to induce apoptosis) as well as separation of two doses by a 24-hr waiting period yielded greater total drug delivery, compared to no fractionation (a single dose all-at-once) or without the waiting period. The in vivo studies used tumor-bearing rats to compare five treatment schedules that, due to differences in dose intensity and dosing frequency, yielded different pharmacodynamics; the results showed tumor priming was necessary to enhance the drug/NM amount in tumors and to promote the intra-tumor drug/NM dispersion (66).

Figure 2. Two requirements for successful tumor priming: Sufficient drug concentration to cause apoptosis and sufficient time for apoptosis to occur.

FaDu tumor histocultures were treated with 10 and 50 nM [3H]paclitaxel continuously. In each figure, the top panels are autoradiographic images overlaid on histological image (253 magnification), and the bottom panels are histological images of the indicated boxed region in the autoradiographic images, at 400× magnification. The indicated times refer to the times after initiation of the [3H]paclitaxel treatment. Reproduced with permission(66).

Tumor priming is effective in tumor histocultures, which are devoid of blood flow or vasculature; its primary mechanism to promote drug/NM delivery and transport in solid tumors is the expansion of interstitial space and the increase in diffusional transport. The mechanisms under in vivo conditions are more complex; we found that tumor priming, again through expansion of interstitial space, resulted in larger patent blood vessels (greater diameter with no change of vessel length or density), expanded blood-perfused areas, and enhanced the extravasation and intra-tumoral dispersion of fluorescent latex nano-beads in solid tumors (18) (Figure 3). The increases in blood flow and blood-perfused areas suggests that, under in vivo conditions, tumor priming increases convective transport in addition to diffusion. The enhanced convective transport in vivo by paclitaxel tumor priming is consistent with the findings of Jain (79).

Figure 3. Systemic tumor priming promotes tumor perfusion and dispersion of nanoparticles in tumor matrix in vivo.

Tumor-bearing mice were given an intravenous injection of the tumor priming agent (40 mg/kg paclitaxel in Cremophor EL®/ethanol) or the vehicle (control), followed by an injection of red fluorescent latex beads (100 nm diameter) at 48 h and an injection of the green fluorescent perfusion marker 3,3′-diheptyloxacarbocyanine iodide at 72 h. Two minutes after the injection of the perfusion marker, tumor and normal tissues were excised and evaluated using computer assisted image analysis. At least five images per section and at least three sections per tumor were analyzed. Four tumors per data point. Bar, 100 μm. The original color pictures, as well as the quantitative image analysis results are shown in our earlier publication (73). The current black-and-white pictures depict the fluorescence signals in white color. (A) Effect of tumor priming on tumor perfusion. Note the increase in the perfused area (white color) after priming in tumor tissues but not in other host normal tissues. (B) Effect of tumor priming on nanoparticle dispersion in tumor matrix. A tumor section was viewed under fluorescence microscope. The fluorescence signals corresponding to nanoparticles are shown in the left figures and the fluorescence signals corresponding to the perfusion marker (of the same tumor tissue section) are shown in the right figures. In the control group, the location of nanoparticles superimposes the location of perfusion marker. In contrast, the priming group shows (a) greater amount of nanoparticles throughout the tumor section and (b) dispersion of nanoparticles away from vessels. Reproduced with permission (18).

The above studies further demonstrate that the various tumor priming effects of paclitaxel pretreatment are tumor selective and not observed in normal tissues (80,81). This is in agreement with the concept that tumor cells are more prone to apoptosis compared to normal tissues. The tumor selectivity of paclitaxel priming was sufficient to significantly enhance the delivery of intravenously administered Doxil® (doxorubicin in pegylated liposomes, 85 nm diameter) to solid tumors without altering the plasma pharmacokinetics or delivery to normal tissues, and was sufficient to improve tumor regression and prolong survival without enhancing host toxicity, in tumor-bearing animals (18).

Our observations on the benefits of using apoptosis-inducing tumor priming to promote drug/NM delivery have been confirmed by other investigators. Li et al. showed that docetaxel pretreatment induced apoptosis, altered the tumor structure (greater interstitial space), and promoted the distribution and transgene expression of an oncolytic prostate-restricted replication competent adenovirus administered by intratumor injection (82). In another study, Nagano et al. found that the induction of apoptosis by caspase-8 activation or cytotoxic agents (paclitaxel or paclitaxel plus tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand) improves the intratumoral penetration and therapeutic efficacy of oncolytic HSV (55). In addition, the dynamic nature and time-dependence of tumor priming explains an earlier finding that the effects of paclitaxel pretreatment on the uptake of huKS-IL2 in murine colon carcinoma was dependent on the time interval between the two treatments (benefits observed only when paclitaxel was administered 24 h but not 1 h before the cytokine (83)).

Collectively, our results indicate that the drug/NM delivery, extravasation and interstitial transport in solid tumors are dynamic processes that can be improved by tumor priming using standard-of-care chemotherapy. More important, these changes were tumor-specific and not observed in normal tissues, thus providing the desired tumor selectivity.

TRANSLATING THE TUMOR-PRIMING TECHNOLOGY INTO POETNTIALLY USEFUL APPLICATIONS

The therapeutic utility of tumor priming for drug/NM delivery depends on successful translation of the current findings to humans. For example, the two requirements of effective paclitaxel tumor priming are its dose and the time window, i.e., sufficient to produce and maintain ~10% apoptosis. Paclitaxel has broad spectrum activity and is used to treat multiple types of human cancers (80,84). That paclitaxel can preferentially induce apoptosis in human tumors is demonstrated by the tumor shrinkage observed in cancer patients. The tumor priming dose of paclitaxel in mice (40 mg/kg) is approximately 100 mg/m2 in humans, which is below the standard dose of 135–225 mg/m2 used in patients (80) and therefore clinically achievable. With respect to the time window, the major determinant is the kinetics of apoptosis. Paclitaxel induces apoptosis at similar rates in murine and human tumors, under in vitro and in vivo conditions. For example, a single dose of paclitaxel (40–60 mg/kg) induced an appreciable level of apoptosis beginning at 9–12 h and ending at 96–120 h, with the peak levels reached between 18–72 h, in transplantable murine carcinoma, in human xenograft tumors in mice, and in histocultures of tumors obtained from cancer patients (79,85,86,87,88). The slow onset and protracted appearance of paclitaxel-induced apoptosis is due to the slow manifestation of apoptosis and the significant intracellular drug retention (89,66). Based on the similarity in the kinetics of paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in animal and human tumors, paclitaxel tumor priming can be readily practiced in clinical settings and, hence, represents a potentially useful method for promoting the delivery and efficacy of NM in patients. Accordingly, we studied and identified the optimal conditions for paclitaxel tumor priming, under two settings, i.e., systemic priming by intravenous paclitaxel and locoregional priming by, e.g., intraperitoneal paclitaxel. Systemic treatments are applicable to situations where the drug/NM enters a tumor via the blood circulation (i.e., outward from vessels into tumor interstitium). Regional treatments are for situations where the drug/NM enters a tumor from the space surrounding the tumor (e.g., inward from the tumor perimeter into the tumor interstitium via the interstitial fluid). As discussed below, these two settings present different requirements for successful tumor priming.

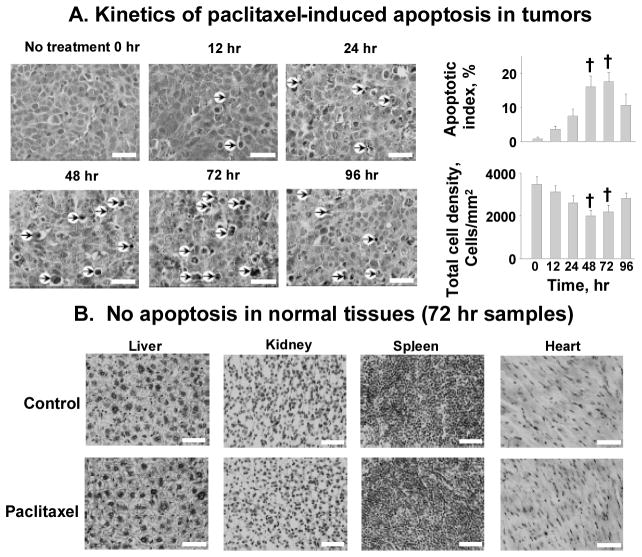

With respect to systemic priming, we found that a single intravenous treatment with paclitaxel (dissolved in Cremophor® micelles and ethanol) yielded the highest levels of apoptotic cells and the greatest reduction of tumor cell density at 48 and 72 h, with the recovery of cell density at 96 h, in tumors grown in mice (Figure 4). Using a cut-off apoptosis of 10% or greater, the boundary time window for intravenous paclitaxel priming is between 24 and 96 h (66,18). Within this time window, intravenous paclitaxel priming significantly enhanced the extravasation and intratumoral dispersion of intravenously administered fluorescent latex beads of up to 200 nm diameter, with no effects on the larger, 500 nm beads. This size restriction, as the beads are delivered via the blood vessels, is likely due to the capillary pore sizes (range from 100 to 780 nm, average cut-off size of 400 nm for nanoparticle extravasation) in tumors (15,90,91).

Figure 4. Kinetics of systemic paclitaxel tumor priming in vivo.

A mouse was given an intravenous injection of paclitaxel (40 mg/kg in Cremophor EL®/ethanol) or the vehicle (control). Tumors and normal tissues were excised and evaluated morphologically. (A) Kinetics of paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in tumors. Changes in apoptotic index and tumor cell density with time were measured. At least five randomly selected regions and at least 3000 cells per tumor and five tumors per time point were evaluated. Arrows, examples of apoptotic cells. (B) No apoptosis in normal tissues (72 h samples). H&E staining (hematoxylin staining for nuclei appeared black in the black-and-white micrograph). Bar, 50 μm. Mean±S.D. Differences between control and tumor priming groups were analyzed using two-sided Student’s t test. †, p < 0.001 compared with time 0 samples. Reproduced with permission (18).

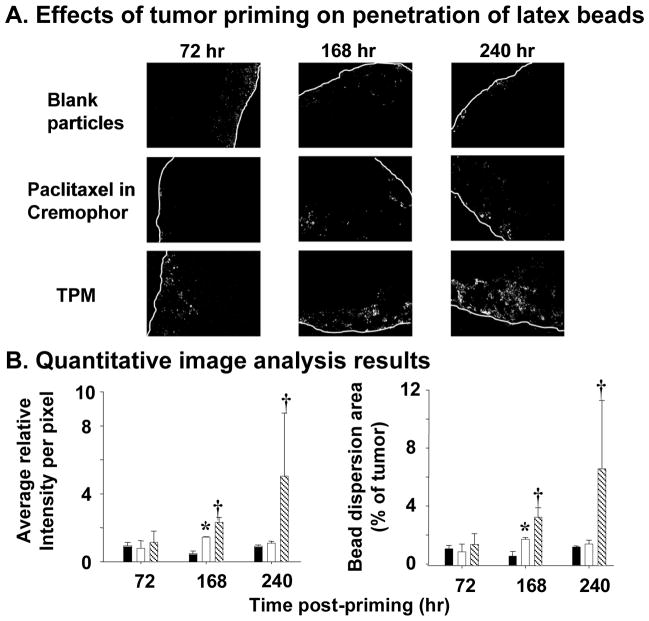

For locoregional priming, the NM size limits are more favorable since the entry of drug/NM into a tumor does not depend on extravasation from blood vessels. For example, an intraperitoneal injection of paclitaxel (dissolved in Cremophor® and ethanol) promoted the penetration of micron-sized, fluorescent latex beads (2 μm) (Figure 5) (92).

Figure 5. Tumor priming promotes penetration of latex beads in intraperitoneal tumors.

Mice bearing intraperitoneal SKOV3 tumors were given an intraperitoneal injection of a tumor priming treatment with either Cremophor EL®/ethanol or the priming TPM (40 mg/kg), followed by an intraperitoneal injection of fluorescent latex beads (2 μm diameter) given 48, 144, and 216 h later. The dose of latex beads was 40 mg/kg (2% solid, 10-fold dilution in normal saline, 0.5 ml per 25 g mice). Control group received blank, drug-free microparticles (i.e., no tumor priming pretreatment). (A) Representative tumor sections showing amount and dispersion of latex beads in tumors. Beads showed red fluorescence (shown as white dots in the black-and-white pictures). White lines indicate the outer perimeter of tumor nodules. 100× magnification. (B) Quantitative image analysis results. The amounts of latex beads in tumors are expressed as (total fluorescence intensity) normalized by (tumor area); a higher value indicates a greater amount. The bead dispersion results are expressed as percentages of tumor occupied by beads; a higher value indicates a greater dispersion. Solid bars, blank particles; open bars, paclitaxel in castor oil/ethanol; hatched bars, TPM. Error bars show 95% confidence intervals. *, elevated bead amounts or dispersion in paclitaxel in castor oil/ethanol group compared with blank particle group at corresponding time points (p <0.05, Student’s t test). †, elevated bead amounts or dispersion in TPM group compared with paclitaxel in castor oil/ethanol or blank particle groups (p <0.05, ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s test). Reproduced with permission (92).

Tumor-penetrating microparticles for bulky peritoneal tumors

The above findings led to the development of tumor-penetrating microparticles (TPM) for treating bulky peritoneal tumors. The peritoneal cavity is a common site of tumor presentation (93). Intraperitoneal (IP) therapy represents a logical alternative method to deliver high drug concentrations to peritoneal tumors, and multiple clinical studies have demonstrated the survival benefits of IP chemotherapy. However, several issues including toxicity and the need of using indwelling catheter for repeated treatments, have prohibited IP therapy from becoming a standard-of-care. Through a series of preclinical pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic studies (92,93,94), we found that the limitations of IP chemotherapy are likely due to the off-label use of formulations intended for intravenous use. For example, we found that the intravenous solution was rapidly cleared from the peritoneal cavity, yielded high drug concentrations in intestinal tissues bathed in the drug solution, and yielded limited drug penetration into tumor nodules. We accordingly designed TPM to overcome these short-comings (92).

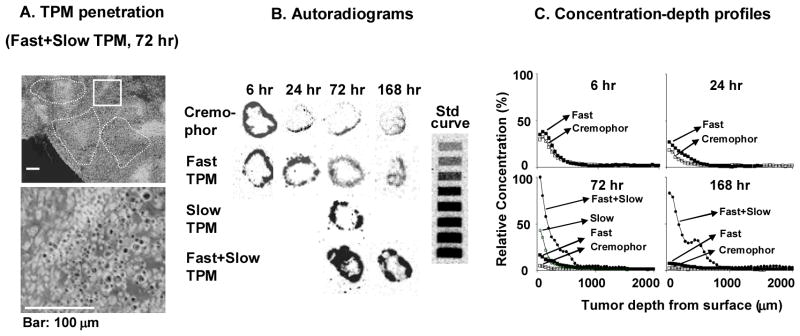

TPM is paclitaxel-loaded particles made of poly-lactide-glycolide copolymers. Its size (4–6 μm) and the polymer glass transition were selected to retard the lymphatic clearance, to promote distribution within the peritoneal cavity, and to selectively adhere to tumor surfaces. TPM further uses the tumor priming technology, and comprises two components. One component releases paclitaxel rapidly (70% of drug load in 1 day under sink conditions) to induce apoptosis (priming component), thereby promoting the penetration of the remaining particles. The second component releases paclitaxel slowly (1% per day) and thereby provides sustained drug levels to achieve extended antitumor effect (sustaining component). These unique features of TPM led to higher and more sustained drug concentrations (16-times higher), lower host toxicity (presumably due to fractionated dose presentation and preferential tumor localization), and greater therapeutic efficacy (longer survival), compared to the intravenous drug solution currently used in IP therapy (paclitaxel dissolved in Cremophor® and ethanol) (92) (Figure 6). The sustained drug levels in tumors eliminate the need of frequent dosing; a single dose of TPM (containing 40 or 120 mg/kg paclitaxel) was equally or more effective compared to multiple divided doses of paclitaxel/Cremophor (4×10 or 8×15 mg/kg) (92).

Figure 6. Effect of tumor priming on spatial drug distribution in tumors: autoradiographic results.

Mice bearing intraperitoneal SKOV3 tumors were given intraperitoneal injections of either paclitaxel/Cremophor EL or priming TPM or sustaining TPM (all at 20 mg/kg) or two-component TPM (40 mg/kg) (1:1 priming/sustaining). (A) TPM penetration into tumor interior. An omental tumor was removed from a mouse at 72 h after treatment with two-component TPM, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The image was converted using Adobe Photoshop; TPM appeared as black dots. Top panel shows areas with clusters of TPM (circumscribed with dotted lines). Bottom panel shows the enlarged picture of the boxed area. (B) autoradiograms of tumor sections (see Materials and Methods in reference (92)). (C) Concentration-depth profiles. Autoradiograms shown in B were processed to obtain measurements of total radioactivity using computer-assisted densitometric analysis. Radioactivity was expressed as paclitaxel equivalents, with the highest level set at 100%. Reproduced with permission (92).

Tumor priming promotes tumor penetration by nano liposomal RNAi csarriers

Since the clinical development of siRNA cancer therapeutics is limited by the poor interstitial transport and inefficient transfection in solid tumors, we explored the possibility of using tumor priming to promote the delivery and efficacy of RNAi therapeutics (95). The study used a non-functional fluorescent siRNA (siGLO®, does not have a mRNA target) and confocal microcopy to monitor transport, and a functional siRNA against survivin and immunostaining and immunoblotting to monitor transfection. The results showed that paclitaxel priming (given 24 or 48 h before siRNA) significantly enhanced the delivery and penetration of siRNA in 3D tumor cultures and the gene knockdown. These findings indicate that paclitaxel tumor priming did not compromise the siRNA functionality, thus offering a promising and practical means to develop chemo-siRNA cancer gene therapy.

In summary, manipulation of tumor interstitium such as paclitaxel tumor priming offers a clinically applicable approach to enhance the delivery and efficacy of cancer NM.

PERSPECTIVES

Nanoparticles can be made of different types of materials and can have different sizes, surface charges and modifications. Hence, there is the potential to tailor the design for its intended function. Such goals can be greatly facilitated by quantitative models that predict the NM delivery to target sites, its disposition at the biointerface, and its interactions with targets. On the other hand, tumors are highly heterogeneous and many tumor properties (a) are dynamic and change with time (e.g., size, blood flow, vascularization status, growth rate, capillary pore size and permeability, extracellular protein contents), (b) depend on the host (e.g., larger tumors in humans than in mice), (c) can change with time (e.g., tumor growth) or with treatments (e.g., cell death due to chemotherapy or irradiation, altered vasculature due to anti-angiogenics), and (d) interdependent where changes in one property can affect other properties (e.g., increase in size will affect the vascularization). Such diverse and dynamic tumor properties create uncertainties on the fate of NM at target sites and hence questions on the NM design. For example, how should one design NM in anticipation of intratumoral heterogeneity in the transport mechanisms (diffusion vs convection) in different parts of a tumor, or treatment-induced changes in tumor vasculature or properties? Are certain NM properties more desirable for smaller or larger tumors? Similarly, some NM properties by design will produce uncertain or opposite outcomes. For example, NM are frequently surface-modified with targeting ligands. But binding of ligands to cell surface receptors limits NM transport. What are the binding characteristics that would yield an optimal balance between tumor selectivity and tumor penetration? Pegylation increases circulation times but also decreases the endocytosis of NM, and some newer NM are designed to shed the pegylation over time (96,10,97,98). What are the range of % pegylation and the rate of “de-pegylation” to enable optimal tumor targeting? We propose that these questions can be addressed by developing computation models to describe the systemic pharmacokinetics and the extravasation, interstitial deposition and transport, and internalization of NM in solid tumors as functions of NM/tumor properties and biointerfaces, and treatment schedules (dose intensity and frequency).

In summary, NM holds promise and enables the development of agents that cannot be readily delivered by the conventional formulations. The utilities of NM can be expanded by new approaches that enhance the selectivity and effectiveness of delivery to organs and intracellular targets. Tumor priming is one of several promising approaches, deserving further exploration and development.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Effectiveness of nanomedicines (NM) in cancer therapy is limited in part by inadequate delivery and transport in tumor interstitium.

Experimental approaches to improve NM delivery and transport in solid tumors include tumor vasculature normalization, interstitial fluid pressure modulation, enzymatic extracellular matrix degradation, and apoptosis-inducing tumor priming technology.

BARRIERS TO NM DELIVERY TO SOLID TUMOR

Barriers to blood-to-tumor transport and extravasation

Compared to normal tissues, tumors have a greater flow resistance and lower blood flow, and consequently lower presentation of NM to tumors.

Tumor blood vessels have discontinuous endothelium and impaired lymphatic system, which results in the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) in tumors.

Approaches to improve the blood-to-tumor transport and extravasation include modulation of MVP and IFP, and tumor vasculature normalization.

Barriers to transport in tumor interstitium

Interstitial transport of NM is mainly by convection that depends on hydraulic conductivity and pressure gradient.

Approaches to improve interstitial transport include enzymatic degradation of ECM, promoting transcytosis, and using tumor-penetrating peptides.

APROACHES TO IMPROVE INTERSTITIAL TRANSPORT

Enzymatic degradation of ECM

Enzymatic degradation of ECM reduces IFP, modifies tumor microenvironment and improves interstitial transport.

Limitations of this approach include concerns of promoting cancer progression, low tumor-selectivity, and dependence on tumor microenvironment.

Promoting transcytosis

NM with transcytosis capability may cross the endothelium and result in accumulation of NM in solid tumors.

Tumor-penetrating peptides

Tumor-penetrating peptide-mediated NM delivery in tumors may be achieved by conjugation or co-administration of the peptide with NM.

Apoptosis-inducing tumor priming

Tissue composition and architecture, tumor cell density and interstitial space are key determinants of the rate and extent of drug/NM penetration in solid tumors.

Apoptosis-inducing tumor priming expands the interstitial space, increases convective transport in addition to diffusion, and thereby promotes the delivery and interstitial transport of NM in tumors.

Tumor-priming is tumor selective and its effect is sufficient to improve NM therapeutic efficacy without enhancing host toxicity.

TRANSLATING THE TUMOR-PRIMING TECHNOLOGY INTO POETNTIALLY USEFUL APPLICATIONS

The two requirements of effective tumor priming are the time window and the dose intensity of the priming agent, i.e., sufficient to produce and maintain ~10% apoptosis.

The tumor priming dose of paclitaxel is clinically achievable.

The kinetics of paclitaxel-induced apoptosis, under in vitro and in vivo conditions, are similar in murine and human tumors, beginning at 9–12 h and ending at 96–120 h.

Tumor-penetrating microparticles (TPM) for bulky peritoneal tumors

TPM is paclitaxel-loaded particles with a defined size (4–6 μm) and polymer glass transition temperature. The size and the polymer properties are selected to retard the lymphatic clearance, to promote distribution within the peritoneal cavity, and to selectively adhere to tumor surfaces.

The tumor priming technology is embedded in the TPM design. TPM comprises two components (priming component and sustaining component). The priming component releases paclitaxel rapidly to induce apoptosis, thereby promoting the penetration of the sustaining component particles that provides sustained drug levels.

Tumor priming promotes tumor penetration of RNAi nanocarriers

Paclitaxel tumor priming significantly enhanced the delivery and penetration of siRNA in 3D tumor cultures without compromising the siRNA functionality.

PERSPECTIVES.

NM can be tailored-made to its intended delivery target and biological functions, by selecting the types of nanomaterials, particle size, surface charge and other modifications. The utilities of NM can be expanded with new approaches that enhance the selectivity and effectiveness of delivery to organs and intracellular targets. Tumor priming is one of several promising approaches, deserving further exploration and development.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported in part by research grants R43CA134047, R43CA121744, R44CA103133, R01CA123159, R01CA158300 and R01EB015253 from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, DHHS.

Abbreviations

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- EPR

enhanced permeability and retention

- HSV

Herpes simplex virus

- IFP

interstitial fluid pressure

- IP

Intraperitoneal

- MVP

microvascular fluid pressure

- NM

Nanomedicines

- RES

reticuloendothelial system

- RNAi

RNA interference

- siRNA

small interference RNA

- TPM

tumor-penetrating microparticles

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Biblography

* of interest

** of considerable interest

- 1.Kim BY, Rutka JT, Chan WC. Nanomedicine. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(25):2434–2443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0912273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moghimi SM, Hunter AC, Murray JC. Nanomedicine: current status and future prospects. FASEB J. 2005;19(3):311–330. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2747rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferrari M. Cancer nanotechnology: opportunities and challenges. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(3):161–171. doi: 10.1038/nrc1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ibrahim NK, Desai N, Legha S, et al. Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of ABI-007, a Cremophor-free, protein-stabilized, nanoparticle formulation of paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(5):1038–1044. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang JA, Xuan T, Parmar M, et al. Development and characterization of a novel liposome-based formulation of SN-38. Int J Pharm. 2004;270(1–2):93–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2003.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim JH, Kim YS, Park K, et al. Antitumor efficacy of cisplatin-loaded glycol chitosan nanoparticles in tumor-bearing mice. J Control Release. 2008;127(1):41–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tuscano JM, Martin SM, Ma Y, Zamboni W, O’Donnell RT. Efficacy, biodistribution, and pharmacokinetics of CD22-targeted pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in a B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma xenograft mouse model. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(10):2760–2768. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chakraborty C, Sarkar B, Hsu CH, Wen ZH, Lin CS, Shieh PC. Future prospects of nanoparticles on brain targeted drug delivery. J Neurooncol. 2009;93(2):285–286. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9759-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma P, Dong X, Swadley CL, et al. Development of idarubicin and doxorubicin solid lipid nanoparticles to overcome Pgp-mediated multiple drug resistance in leukemia. J Biomed Nanotechnol. 2009;5(2):151–161. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2009.1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J, Lu Z, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Delivery of siRNA Therapeutics: Barriers and Carriers. AAPS J. 2010;12(4):492–503. doi: 10.1208/s12248-010-9210-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nie S. Understanding and overcoming major barriers in cancer nanomedicine. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2010;5(4):523–528. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis ME, Chen ZG, Shin DM. Nanoparticle therapeutics: an emerging treatment modality for cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(9):771–782. doi: 10.1038/nrd2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitehead KA, Langer R, Anderson DG. Knocking down barriers: advances in siRNA delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8(2):129–138. doi: 10.1038/nrd2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang J, Lu Z, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Delivery of siRNA Therapeutics: Barriers and Carriers. AAPS J. 2010 doi: 10.1208/s12248-010-9210-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jang SH, Wientjes MG, Lu D, Au JL. Drug delivery and transport to solid tumors. Pharm Res. 2003;20(9):1337–1350. doi: 10.1023/a:1025785505977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cairns R, Papandreou I, Denko N. Overcoming physiologic barriers to cancer treatment by molecularly targeting the tumor microenvironment. Mol Cancer Res. 2006;4(2):61–70. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexis F, Pridgen E, Molnar LK, Farokhzad OC. Factors affecting the clearance and biodistribution of polymeric nanoparticles. Mol Pharm. 2008;5(4):505–515. doi: 10.1021/mp800051m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18**.Lu D, Wientjes MG, Lu Z, Au JL. Tumor priming enhances delivery and efficacy of nanomedicines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2007;322(1):80–88. doi: 10.1124/jpet.107.121632. Systemic tumor priming enhances delivery and efficacy of nanomedicines. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki M, Hori K, Abe I, Saito S, Sato H. A new approach to cancer chemotherapy: selective enhancement of tumor blood flow with angiotensin II. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1981;67:663–669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tong RT, Boucher Y, Kozin SV, Winkler F, Hicklin DJ, Jain RK. Vascular normalization by vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 blockade induces a pressure gradient across the vasculature and improves drug penetration in tumors. Cancer Res. 2004;64(11):3731–3736. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagamitsu A, Greish K, Maeda H. Elevating blood pressure as a strategy to increase tumor-targeted delivery of macromolecular drug SMANCS: cases of advanced solid tumors. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39(11):756–766. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyp074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang E, Chalikonda S, Friedl J, et al. Targeting vaccinia to solid tumors with local hyperthermia. Hum Gene Ther. 2005;16(4):435–444. doi: 10.1089/hum.2005.16.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kong G, Braun RD, Dewhirst MW. Hyperthermia enables tumor-specific nanoparticle delivery: effect of particle size. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4440–4445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le Serve AW, Hellmann K. Metastases and the normalization of tumour blood vessels by ICRF 159: a new type of drug action. Br Med J. 1972;1(5800):597–601. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5800.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jain RK. Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science. 2005;307(5706):58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1104819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tailor TD, Hanna G, Yarmolenko PS, et al. Effect of pazopanib on tumor microenvironment and liposome delivery. Mol Cancer Ther. 2010;9(6):1798–1808. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin MI, Sessa WC. Antiangiogenic therapy: creating a unique “window” of opportunity. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(6):529–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winkler F, Kozin SV, Tong RT, et al. Kinetics of vascular normalization by VEGFR2 blockade governs brain tumor response to radiation: role of oxygenation, angiopoietin-1, and matrix metalloproteinases. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(6):553–563. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dickson PV, Hamner JB, Sims TL, et al. Bevacizumab-induced transient remodeling of the vasculature in neuroblastoma xenografts results in improved delivery and efficacy of systemically administered chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13(13):3942–3950. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maeda H, Noguchi Y, Sato K, Akaike T. Enhanced vascular permeability in solid tumor is mediated by nitric oxide and inhibited by both new nitric oxide scavenger and nitric oxide synthase inhibitor. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1994;85(4):331–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1994.tb02362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Seki T, Fang J, Maeda H. Enhanced delivery of macromolecular antitumor drugs to tumors by nitroglycerin application. Cancer Sci. 2009;100(12):2426–2430. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yasuda H, Nakayama K, Watanabe M, et al. Nitroglycerin treatment may enhance chemosensitivity to docetaxel and carboplatin in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(22):6748–6757. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yasuda H, Yamaya M, Nakayama K, et al. Randomized phase II trial comparing nitroglycerin plus vinorelbine and cisplatin with vinorelbine and cisplatin alone in previously untreated stage IIIB/IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(4):688–694. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.0436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li J, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Pancreatic cancer: pathobiology, treatment options, and drug delivery. AAPS J. 2010;12(2):223–232. doi: 10.1208/s12248-010-9181-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olson P, Hanahan D. Cancer. Breaching the cancer fortress. Science. 2009;324(5933):1400–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1175940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Netti PA, Berk DA, Swartz MA, Grodzinsky AJ, Jain RK. Role of extracellular matrix assembly in interstitial transport in solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2000;60(9):2497–2503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi J, Credit K, Henderson K, et al. Intraperitoneal immunotherapy for metastatic ovarian carcinoma: Resistance of intratumoral collagen to antibody penetration. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(6):1906–1912. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olive KP, Jacobetz MA, Davidson CJ, et al. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science. 2009;324(5933):1457–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.1171362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tian H, Callahan CA, DuPree KJ, et al. Hedgehog signaling is restricted to the stromal compartment during pancreatic carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(11):4254–4259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813203106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brown E, McKee T, diTomaso E, et al. Dynamic imaging of collagen and its modulation in tumors in vivo using second-harmonic generation. Nat Med. 2003;9(6):796–800. doi: 10.1038/nm879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKee TD, Grandi P, Mok W, et al. Degradation of fibrillar collagen in a human melanoma xenograft improves the efficacy of an oncolytic herpes simplex virus vector. Cancer Res. 2006;66(5):2509–2513. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eikenes L, Bruland OS, Brekken C, Davies CL. Collagenase increases the transcapillary pressure gradient and improves the uptake and distribution of monoclonal antibodies in human osteosarcoma xenografts. Cancer Res. 2004;64(14):4768–4773. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eikenes L, Tari M, Tufto I, Bruland OS, de Lange DC. Hyaluronidase induces a transcapillary pressure gradient and improves the distribution and uptake of liposomal doxorubicin (Caelyx) in human osteosarcoma xenografts. Br J Cancer. 2005;93(1):81–88. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stetler-Stevenson WG. Dynamics of matrix turnover during pathologic remodeling of the extracellular matrix. Am J Pathol. 1996;148(5):1345–1350. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Magzoub M, Jin S, Verkman AS. Enhanced macromolecule diffusion deep in tumors after enzymatic digestion of extracellular matrix collagen and its associated proteoglycan decorin. FASEB J. 2008;22(1):276–284. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9150com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46*.Mok W, Boucher Y, Jain RK. Matrix metalloproteinases-1 and -8 improve the distribution and efficacy of an oncolytic virus. Cancer Res. 2007;67(22):10664–10668. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3107. Enzymatic extracellular matrix degradation improves delivery and efficacy of HSV. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goodman TT, Olive PL, Pun SH. Increased nanoparticle penetration in collagenase-treated multicellular spheroids. Int J Nanomedicine. 2007;2(2):265–274. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albanell J, Baselga J. Systemic therapy emergencies. Semin Oncol. 2000;27(3):347–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maier U, Baumgartner G. Metaphylactic effect of mitomycin C with and without hyaluronidase after transurethral resection of bladder cancer: randomized trial. J Urol. 1989;141(3):529–530. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)40881-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith KJ, Skelton HG, Turiansky G, Wagner KF. Hyaluronidase enhances the therapeutic effect of vinblastine in intralesional treatment of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Military Medical Consortium for the Advancement of Retroviral Research (MMCARR) J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997;36(2 Pt 1):239–242. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(97)70288-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brinckerhoff CE, Rutter JL, Benbow U. Interstitial collagenases as markers of tumor progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(12):4823–4830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roy R, Yang J, Moses MA. Matrix metalloproteinases as novel biomarkers and potential therapeutic targets in human cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(31):5287–5297. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.5556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kovar JL, Johnson MA, Volcheck WM, Chen J, Simpson MA. Hyaluronidase expression induces prostate tumor metastasis in an orthotopic mouse model. Am J Pathol. 2006;169(4):1415–1426. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tannock IF, Rotin D. Acid pH in tumors and its potential for therapeutic exploitation. Cancer Res. 1989;49(16):4373–4384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagano S, Perentes JY, Jain RK, Boucher Y. Cancer cell death enhances the penetration and efficacy of oncolytic herpes simplex virus in tumors. Cancer Res. 2008;68(10):3795–3802. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kawai M, Higuchi H, Takeda M, Kobayashi Y, Ohuchi N. Dynamics of different-sized solid-state nanocrystals as tracers for a drug-delivery system in the interstitium of a human tumor xenograft. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11(4):R43. doi: 10.1186/bcr2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Desai N, Trieu V, Yao Z, et al. Increased antitumor activity, intratumor paclitaxel concentrations, and endothelial cell transport of cremophor-free, albumin-bound paclitaxel, ABI-007, compared with cremophor-based paclitaxel. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(4):1317–1324. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Desai N, Trieu V, Damascelli B, Soon-Shiong P. SPARC Expression Correlates with Tumor Response to Albumin-Bound Paclitaxel in Head and Neck Cancer Patients. Transl Oncol. 2009;2(2):59–64. doi: 10.1593/tlo.09109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Von Hoff DD, Ramanathan R, Borad M, et al. SPARC correlation with response to gemcitabine (G) plus nab-paclitaxel (nab-P) in patients with advanced metastatic pancreatic cancer: A phase I/II study. J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2009;27(15S):4525. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hamilton EP, Kimmick GG, Desai N, et al. Use of SPARC, EGFR, and VEGFR expression to predict response to nab-paclitaxel (nabP)/carboplatin (C)/bevacizumab (B) chemotherapy in triple-negative metastatic breast cancer (TNMBC) J Clin Oncol (Meeting Abstracts) 2010;28(15_suppl):1109. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sugahara KN, Teesalu T, Karmali PP, et al. Tissue-penetrating delivery of compounds and nanoparticles into tumors. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(6):510–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sugahara KN, Teesalu T, Karmali PP, et al. Coadministration of a tumor-penetrating peptide enhances the efficacy of cancer drugs. Science. 2010;328(5981):1031–1035. doi: 10.1126/science.1183057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Desgrosellier JS, Cheresh DA. Integrins in cancer: biological implications and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(1):9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Teesalu T, Sugahara KN, Kotamraju VR, Ruoslahti E. C-end rule peptides mediate neuropilin-1-dependent cell, vascular, and tissue penetration. Proc Natl Acad SciUS A. 2009;106(38):16157–16162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908201106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Au JLS, Jang SH, Zheng J, et al. Determinants of drug delivery and transport to solid tumors. J Control Release. 2001;74(1–3):31–46. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(01)00308-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66**.Jang SH, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Enhancement of paclitaxel delivery to solid tumors by apoptosis-inducing pretreatment: effect of treatment schedule. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296(3):1035–1042. Time- and concentration-dependent penetration and accumulation of protein-bound drugs in histocultures of solid tumor. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jang SH, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Determinants of paclitaxel uptake, accumulation and retention in solid tumors. Invest New Drugs. 2001;19(2):113–123. doi: 10.1023/a:1010662413174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68**.Kuh HJ, Jang SH, Wientjes MG, Weaver JR, Au JL. Determinants of paclitaxel penetration and accumulation in human solid tumor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290(2):871–880. Time- and concentration-dependent penetration and accumulation of protein-bound drugs in histocultures of solid tumor. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69**.Zheng JH, Chen CT, Au JL, Wientjes MG. Time- and concentration-dependent penetration of doxorubicin in prostate tumors. AAPS PharmSci. 2001;3(2):E15. doi: 10.1208/ps030215. Time- and concentration-dependent penetration and accumulation of protein-bound drugs in histocultures of solid tumor. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kuh HJ, Jang SH, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Computational model of intracellular pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;293(3):761–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schultz JS, Armstrong W. Permeability of interstitial space of muscle (rat diaphragm) to solutes of different molecular weights. J Pharm Sci. 1978;67(5):696–700. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600670534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Au JLS, Li D, Gan Y, et al. Pharmacodynamics of immediate and delayed effects of paclitaxel: role of slow apoptosis and intracellular drug retention. Cancer Res. 1998;58:2141–2148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Au JLS, Kumar RR, Li D, Wientjes MG. Kinetics of hallmark biochemical changes in paclitaxel-induced apoptosis. AAPS PharmSci. 1999;1(3):E8. doi: 10.1208/ps010308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chen CT, Au JL, Wientjes MG. Pharmacodynamics of doxorubicin in human prostate tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4(2):277–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cheng L, Zheng S, Raghunathan K, et al. Characterisations of taxolinduced apoptosis and altered gene expression in human breast cancer cells. Cell Pharmacol. 1995;2:249–257. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gan Y, Wientjes MG, Schuller DE, Au JLS. Pharmacodynamics of taxol in human head and neck tumors. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2086–2093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Milas L, Hunter NR, Kurdoglu B, et al. Kinetics of mitotic arrest and apoptosis in murine mammary and ovarian tumors treated with taxol. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1995;35:297–303. doi: 10.1007/BF00689448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Saunders DE, Lawrence WD, Christensen C, Wappler NL, Ruan H, Deppe G. Paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in MCF7 breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 1997;70:214–220. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970117)70:2<214::aid-ijc13>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Griffon-Etienne G, Boucher Y, Brekken C, Suit Hd, Jain RK. Taxane-induced apoptosis decompresses blood vessels and lowers interstitial fluid pressure in solid tumors: clinical implications. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3776–3782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rowinsky EK, Wright M, Monsarrat B, Lesser GJ, Donehower RC. Taxol: pharmacology, metabolism, and clinical applications. Cancer Surv. 1993;17:283–304. Pharmacokinetics and Cancer Chemotherapy. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rowinsky EK, Donehower RC. Paclitaxel (taxol) N Engl J Med. 1995;332(15):1004–1014. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504133321507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li X, Liu Y, Tang Y, Roger P, Jeng MH, Kao C. Docetaxel increases antitumor efficacy of oncolytic prostate-restricted replicative adenovirus by enhancing cell killing and virus distribution. J Gene Med. 2010;12(6):516–527. doi: 10.1002/jgm.1462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Holden SA, Lan Y, Pardo AM, Wesolowski JS, Gillies SD. Augmentation of antitumor activity of an antibody-interleukin 2 immunocytokine with chemotherapeutic agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(9):2862–2869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Spencer CM, Faulds D. Paclitaxel. A review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic potential in the treatment of cancer. Drugs. 1994;48(5):794–847. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199448050-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Millenbaugh NJ, Gan Y, Au JLS. Cytostatic and apoptotic effects of paclitaxel in human ovarian tumors. Pharm Res. 1998;15:122–127. doi: 10.1023/a:1011969208114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gan Y, Wientjes MG, Lu J, Au JL. Cytostatic and apoptotic effects of paclitaxel in human breast tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1998;42(3):177–182. doi: 10.1007/s002800050803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chen CT, Gan Y, Au JL, Wientjes MG. Androgen-dependent and -independent human prostate xenograft tumors as models for drug activity evaluation. Cancer Res. 1998;58(13):2777–2783. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Au JLS, Kalns J, Gan Y, Wientjes MG. Pharmacologic effects of taxol in human bladder tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1997;41:69–74. doi: 10.1007/s002800050709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Au JL, Li D, Gan Y, et al. Pharmacodynamics of immediate and delayed effects of paclitaxel: role of slow apoptosis and intracellular drug retention. Cancer Res. 1998;58(10):2141–2148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yuan F, Dellian M, Fukumura D, et al. Vascular permeability in a human tumor xenograft: molecular size dependence and cutoff size. Cancer Res. 1995;55(17):3752–3756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Less JR, Skalak TC, Sevick EM, Jain RK. Microvascular architecture in a mammary carcinoma: branching patterns and vessel dimensions. Cancer Res. 1991;51:265–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92**.Lu Z, Tsai M, Lu D, Wang J, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Tumor-penetrating microparticles for intraperitoneal therapy of ovarian cancer. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;327(3):673–682. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.140095. Tumor priming enhances NM tumor delivery in regional IP therapy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lu Z, Wang J, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Intraperitoneal therapy for peritoneal cancer. Future Oncol. 2010;6(10):1625–1641. doi: 10.2217/fon.10.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tsai M, Lu Z, Wang J, Yeh TK, Wientjes MG, Au JL. Effects of carrier on disposition and antitumor activity of intraperitoneal Paclitaxel. Pharm Res. 2007;24(9):1691–1701. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9298-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95**.Wong Ho Lun, Shen Zancong, Lu Ze, Guillaume Wientjes M, Au Jessie. Paclitaxel Tumor-Priming Enhances siRNA Delivery and Transfection in 3-Dimensional Tumor Cultures. 2011. Tumor priming enhances RNAi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Santel A, Aleku M, Keil O, et al. A novel siRNA-lipoplex technology for RNA interference in the mouse vascular endothelium. Gene Ther. 2006;13(16):1222–1234. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Alexis F, Pridgen E, Molnar LK, Farokhzad OC. Factors affecting the clearance and biodistribution of polymeric nanoparticles. Mol Pharm. 2008;5(4):505–515. doi: 10.1021/mp800051m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Li SD, Huang L. Pharmacokinetics and biodistribution of nanoparticles. Mol Pharm. 2008;5(4):496–504. doi: 10.1021/mp800049w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99*.Abe I, Hori K, Saito S, Tanda S, Li YL, Suzuki M. Increased intratumor concentration of fluorescein-isothiocyanatelabeled neocarzinostatin in rats under angiotensin-induced hypertension. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1988;79:874–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1988.tb00050.x. Angiotensin II promotes protein tumor delivery. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]